Optimization of Energy Consumption in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: An Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

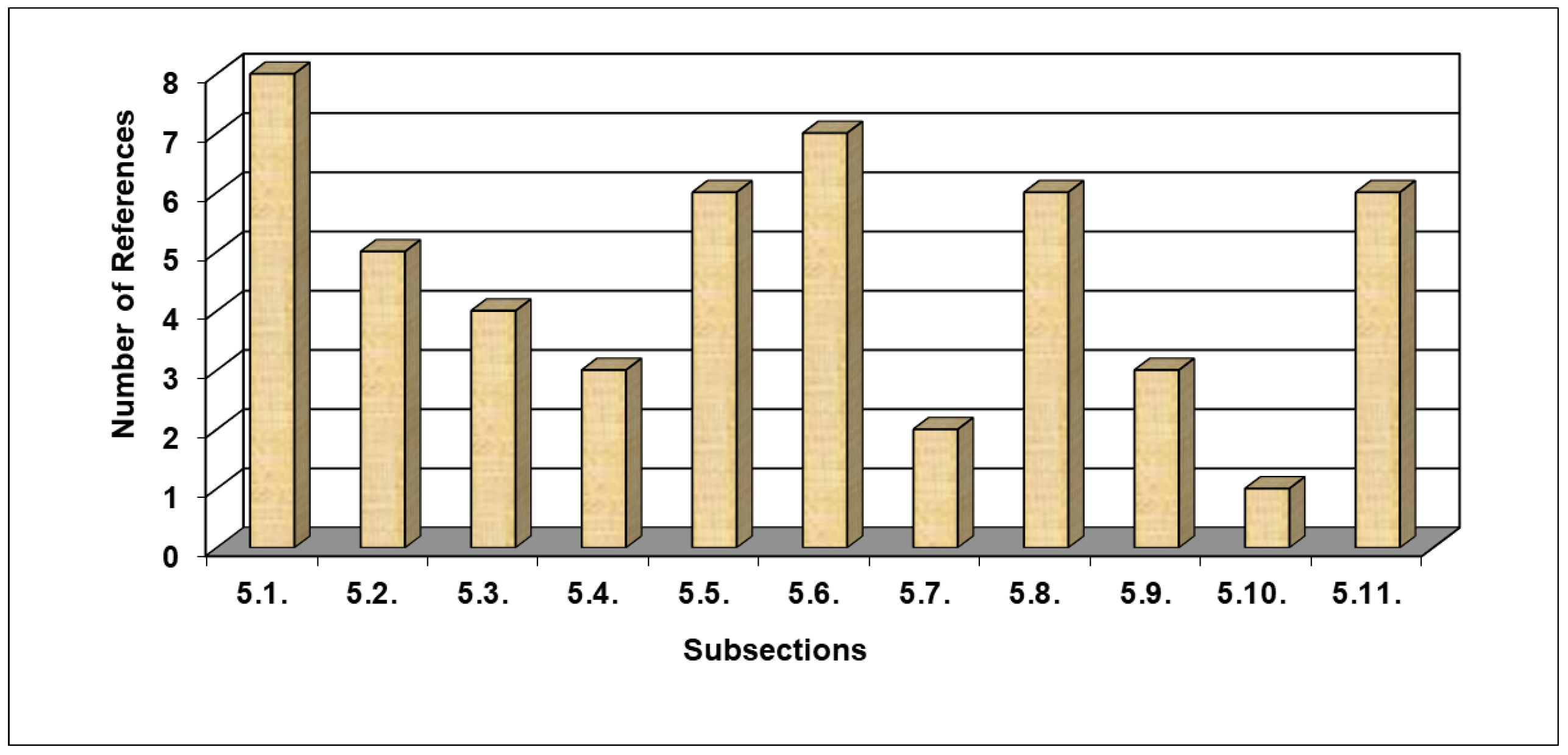

2. Methodology

- 5.1. Energy optimization during aeration process;

- 5.2. Proposed methods to reduction in energy during sludge treatment;

- 5.3. Emphasizing multiple stages of WWT;

- 5.4. Modification in the operation of the pumps;

- 5.5. Addition of equipment and utilization of existing infrastructure;

- 5.6. Application of renewable energy sources;

- 5.7. Modeling individual processes in WWTPs;

- 5.8. Simulation for predicting energy consumption;

- 5.9. Comparative evaluation between various WWTPs;

- 5.10. Theoretical thermodynamic study;

- 5.11. Other case studies.

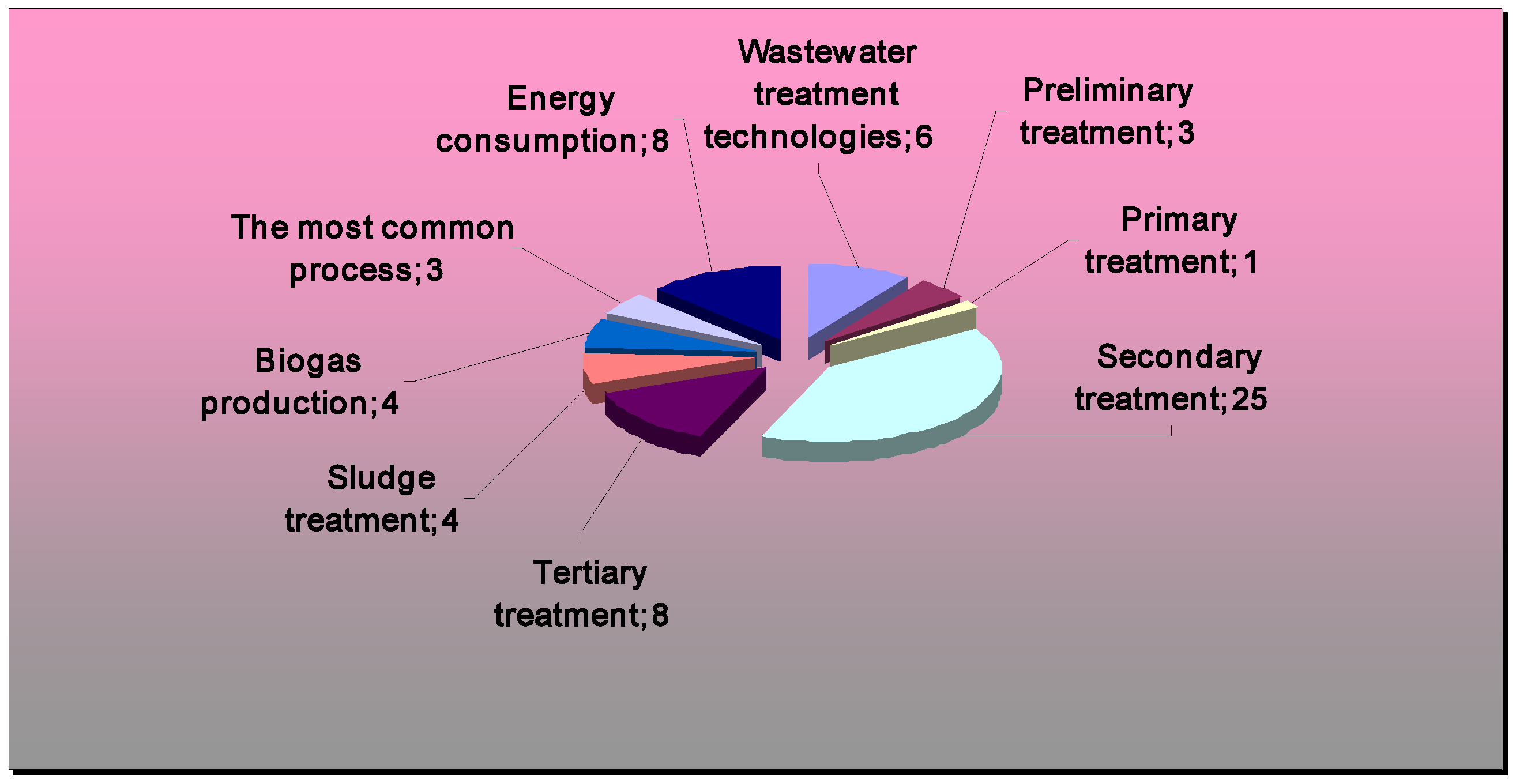

3. WWT Technologies

- Preliminary

- Primary

- Secondary

- Tertiary

3.1. Preliminary Treatment

- Collection Systems: Proper planning of collection systems is crucial, necessitating analysis of population and flow projections. Designs should incorporate long-term growth patterns and water consumption data to effectively accommodate future expansions;

- Screening: The removal of debris such as rags and plastic is essential to prevent equipment damage. Screening methods can be either manual or mechanical, but ensuring the proper disposal of removed waste is crucial to prevent health hazards and odors;

- Grit Removal: Grit, comprising sand and small stones, can cause mechanical equipment damage if left untreated. Grit removal protects pumps and equipment from abrasion, ensuring smooth operation;

- Comminution: Solid materials are reduced in size through processes like crushing or grinding to facilitate downstream treatment processes;

- Disposal of Screenings and Grit: Proper disposal of screenings and grit is paramount to avoid odor and hygiene issues. Suitable containers with lids are utilized for disposal, and in smaller plants, burial in trenches is an option, followed by prompt covering with soil to prevent odors and pests.

3.2. Primary Treatment

3.3. Secondary Treatment

3.4. Tertiary Treatment

- Constructed wetlands [49,50]: These artificial wetlands use granular material to facilitate effluent flow, with reeds planted on the surface. They effectively remove inorganic nutrients, process organic waste, and reduce suspended sediments. Wetland configurations include surface and subsurface flow, catering to different climatic conditions [51];

- Ecosystem technologies: Inspired by natural ecosystems, these technologies replicate hydrological and mineral cycles. Living machines assemble organisms tailored to project goals, mimicking natural processes for effective water treatment [20];

- Ozonation: Ozone disinfection [20], favored for its quick action and on-site production, requires proper dosage, mixing, and contact time for effective pathogen removal. Pilot testing and calibration ensure system efficiency before installation;

- UV radiation: UV disinfection [54], though less common, relies on factors like effluent transmissivity and radiation intensity for microbial inactivation;

- Maturation ponds: These ponds refine effluents, improving bacteriological quality and serving as buffers during operational disruptions. Proper maintenance minimizes nuisances and promotes plant growth, necessitating management measures. Specific directives ensure discharged effluent meets quality standards [55,56].

3.5. Sludge Handling

- Raw or primary (from primary settling tanks);

- Anaerobically digested;

- Oxidation pond;

- Septic tank;

- Waste activated (sludge wasted from an activated sludge plant);

- Humus tank;

- Composted.

- Thickening: Before undergoing digestion, sludge is commonly thickened to decrease [60] its water content and optimize the utilization of digester capacity. This thickening process serves to prevent dilution of feed material, thereby reducing energy requirements for heating and maintaining pH stability within the digester. Various methods, such as gravity thickeners or dissolved air flotation thickeners, are utilized for this purpose, ensuring that the sludge is concentrated adequately for effective digestion without impeding pumping and mixing processes;

- Stabilization: Anaerobic digestion stands as a prevalent method for stabilizing sludge, transforming it from a malodorous and readily decomposable state into a mostly odorless and stable material suitable for disposal. During this process, acid-forming bacteria decompose organic matter into organic acids, which subsequently undergo conversion into methane and carbon dioxide. Despite requiring substantial investment and skilled operators, effectively managed anaerobic digestion can yield biogas suitable for power generation;

- Dewatering: Dewatering plays a critical role in reducing the volume of sludge for disposal. Various methods, including filter or belt presses and drying beds, are employed to extract water from the sludge. In the filter or belt presses, flocculants are introduced to aid in dewatering, while drying beds rely on sand filters to drain water from the sludge during the drying process. Ensuring proper maintenance of equipment like belt presses is essential to prevent problems such as sludge buildup.

3.6. Biogas Production

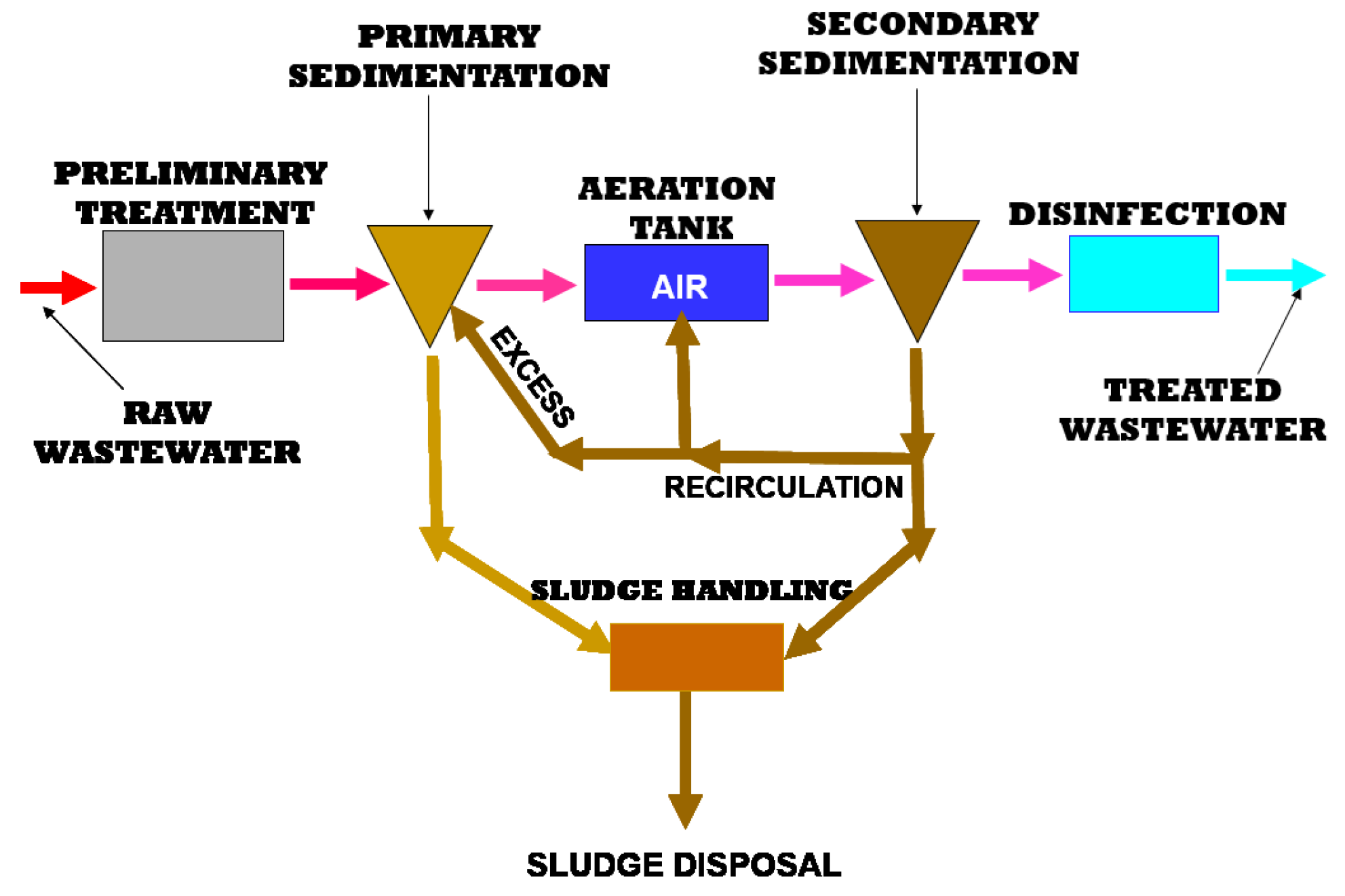

3.7. The Most Common Process

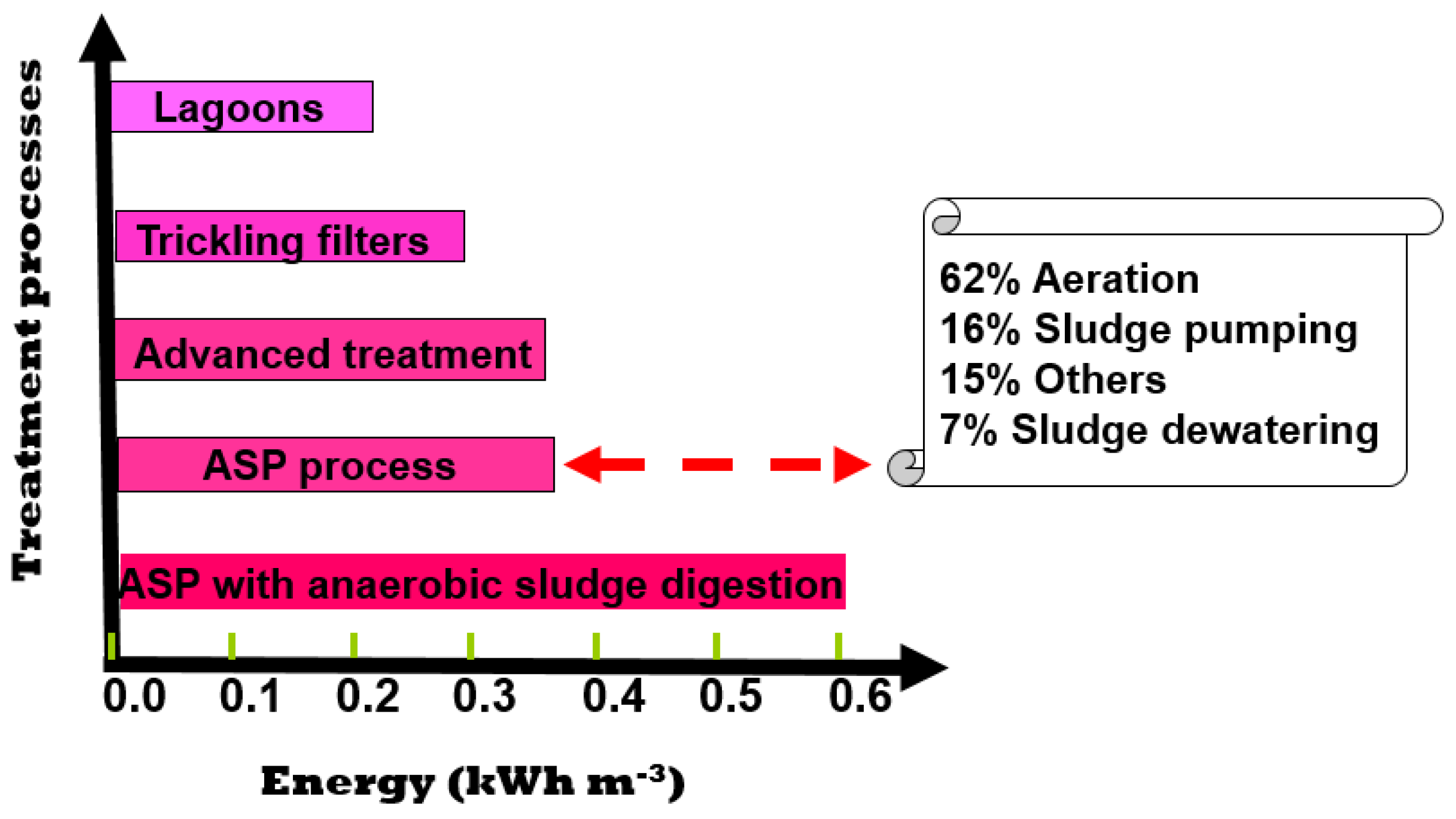

4. Energy Consumption

5. Overview

5.1. Energy Optimization during Aeration Process

5.2. Proposed Methods to Reduction in Energy during Sludge Treatment

5.3. Emphasizing Multiple Stages of WWT

5.4. Modification in the Operation of the Pumps

5.5. Addition of Equipment and Utilization of Existing Infrastructure

5.6. Application of Renewable Energy Sources

5.7. Modeling Individual Processes in WWTPs

5.8. Simulation for Predicting Energy Consumption

5.9. Comparative Evaluation between Various WWTPs

5.10. Theoretical Thermodynamic Study

5.11. Other Case Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABAC | Ammonia-Based Aeration Control |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ATAD | Autothermal Thermophilic Aerobic Digestion |

| AVN | Ammonia vs. Nitrate |

| AWWTPs | Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plants |

| ASP | Activated Sludge Process |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| CANON | Completely Autotrophic Nitrogen Removal Over Nitrite |

| CBOD | Carbonaceous Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| CEPT | Chemically Enhanced Primary Treatment |

| CF | Carbon Footprint |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| DRT | Dryer Residence Time |

| EEMs | Energy-Efficient Motors |

| EU | European Union |

| FBF | Fluidized Bed Furnace |

| FOG | Fat-Oil-Grease |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GWh | Gigawatt-hour |

| HEXs | Heat Exchangers |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| kWh | Kilowatt-hour |

| kWh g−1 | Kilowatt hour per kilogram |

| MLR | Mixed Liquor Recirculation |

| MWh | Megawatt-hour |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| NO3 | Nitrate |

| N-NH4 | Ammonium |

| NO2 | Nitrite |

| PE | Population Equivalent |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PI | Precipitation |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| Qin | Influent flow rate |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| SAF-MBR | Staged Anaerobic Fluidized Membrane Bioreactor |

| SBR | Sequencing Batch Reactor |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SEG | Seine-Grésillon |

| SHTR | Steam Heat Transfer Rate |

| SS | Suspended Solids |

| SRT | Solids Retention Time |

| TDP | Total Dissolved Particles |

| TFB | Turbulent Fluidized Bed |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TSP | Total Suspended Particles |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| UASB | Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket Reactor |

| USA | United States of America |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VFDs | Variable Frequency Drives |

| VSDs | Variable Speed Drives |

| WWTP(s) | Wastewater Treatment Plants |

| WWT | Wastewater Treatment |

| WWTWs | Wastewater Treatment Works |

References

- Zhang, Z.; Kusiak, A. Models for Optimization of Energy Consumption of Pumps in a Wastewater Processing Plant. J. Energy Eng. 2011, 137, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, C.; Coughlan, P.; McNabola, A. Microhydropower Energy Recovery at Wastewater-Treatment Plants: Turbine Selection and Optimization. J. Energy Eng. 2017, 143, 04016036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacicco, A.; Zacchei, E. Optimization of Energy Consumptions of Oxidation Tanks in Urban Wastewater Treatment Plants with Solar Photovoltaic Systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.; Zhelev, T. Energy Efficiency Optimisation of Wastewater Treatment: Study of ATAD. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2012, 38, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, P.E.; Mainardis, M.; Moretti, A.; Cottes, M. 100% Renewable Wastewater Treatment Plants: Techno-Economic Assessment Using a Modelling and Optimization Approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 239, 114214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masłoń, A. Analysis of Energy Consumption at the Rzeszów Wastewater Treatment Plant. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 22, 00115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunberg, A.; Sundin, A.-M.; Carlsson, B.; Association, K. Energy Optimization of the Aeration Process at Käppala Wastewater Treatment Plant. In Proceedings of the 10th IWA Conference on Instrumentation, Control & Automation, Cairns, Australia, 14–27 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mountouris, A.; Voutsas, E.; Tassios, D. Plasma Gasification of Sewage Sludge: Process Development and Energy Optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, O.; Enderle, P.; Varbanov, P. Ways to Optimize the Energy Balance of Municipal Wastewater Systems: Lessons Learned from Austrian Applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 88, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awe, O.W.; Liu, R.; Zhao, Y. Analysis of Energy Consumption and Saving in Wastewater Treatment Plant: Case Study from Ireland. J. Water Sustain. 2016, 6, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nakkasunchi, S.; Hewitt, N.J.; Zoppi, C.; Brandoni, C. A Review of Energy Optimization Modelling Tools for the Decarbonisation of Wastewater Treatment Plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Linville, J.L.; Urgun-Demirtas, M.; Mintz, M.M.; Snyder, S.W. An Overview of Biogas Production and Utilization at Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities towards Energy-Neutral WWTPs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panepinto, D.; Fiore, S.; Zappone, M.; Genon, G.; Meucci, L. Evaluation of the Energy Efficiency of a Large Wastewater Treatment Plant in Italy. Appl. Energy 2016, 161, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englande, A.J.; Krenkel, P.; Shamas, J. Wastewater Treatment & Water Reclamation. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9780124095489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Akhtar, M.D.; Khan, M.T.; Jamshed, J. Sewage Treatment Plant (Stp). Int. J. Adv. Res. Dev. 2017, 2, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.A. Wastewater Treatment and Reuse for Sustainable Water Resources Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaonkar, G.V. A Review on Wastewater Treatment Techniques. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2019, 6, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, S. Wastewater Characteristics, Treatment and Disposal; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E. Wastewater Treatment: An Overview. In Green Adsorbents for Pollutant Removal; Crini, G., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Environmental Chemistry for a Sustainable World; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 18, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Research Commission. Wastewater Treatment Technologies: A Basic Guide; Water Research Commission: Gezina, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sidwick, J.M. The Preliminary Treatment of Wastewater. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1991, 52, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.W. Preliminary Wastewater Treatment. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-10/tawebinar_preliminarywastewatertreatment_230725.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Partners, G.; Macero, E.; Guyer, J.P. An Introduction to Preliminary Wastewater Treatment; Continuing Education and Development Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Von Sperling, M. Basic Principles of Wastewater Treatment; Biological Wastewater Treatment Series; IWA Publishing [u.a.]: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, L.T.; Van Echelpoel, W.; Goethals, P.L.M. Design of Waste Stabilization Pond Systems: A Review. Water Res. 2017, 123, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroga, F.J.T. Waste Stabilization Ponds for Waste Water Treatment, Anaerobic Pond. Environ. Sci. 2005, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, E.; Calijuri, M.L.; Assemany, P.; Cecon, P.R. Evaluation of High Rate Ponds Operational and Design Strategies for Algal Biomass Production and Domestic Wastewater Treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargava, A.; Lakmini, S. Land Treatment as Viable Solution for Waste Water Treatment and Disposal in India. J. Earth Sci. Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, S. Slow-Rate Land Treatment. Available online: https://snapp.icra.cat/factsheets/01_Slow%20rate.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Mousavinezhad, M.; Rezazadeh, M.; Golbabayee, F.; Sadati, E. Land Treatment Methods A Review on Available Methods and Its Ability to Remove Pollutants. Orient. J. Chem. 2015, 31, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet: Slow Rate Land Treatment; Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- Chan, Y.J.; Chong, M.F.; Law, C.L.; Hassell, D.G. A Review on Anaerobic–Aerobic Treatment of Industrial and Municipal Wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 155, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardis, M.; Buttazzoni, M.; Goi, D. Up-Flow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB) Technology for Energy Recovery: A Review on State-of-the-Art and Recent Technological Advances. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daud, M.K.; Rizvi, H.; Akram, M.F.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Nafees, M.; Jin, Z.S. Review of Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket Reactor Technology: Effect of Different Parameters and Developments for Domestic Wastewater Treatment. J. Chem. 2018, 2018, 1596319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnaji, C.C. A Review of the Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket Reactor. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 52, 4122–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodík, I.; Herdová, B.; Kratochvíl, K. The Application of Anaerobic Filter for Municipal Wastewater Treatment. Chem. Pap. 2000, 54, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Manariotis, I.D.; Grigoropoulos, S.G. Anaerobic Filter Treatment of Municipal Wastewater: Biosolids Behavior. J. Environ. Eng. 2006, 132, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkhe, S. Development of an Improved Anaerobic Filter for Municipal Wastewater Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahansazan, B.; Afrashteh, H.; Ahansazan, N.; Ahansazan, Z. Activated Sludge Process Overview. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2014, 5, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Orhon, D. Evolution of the Activated Sludge Process: The First 50 Years. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 90, 608–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.K.; Wu, Z.; Shammas, N.K. Activated Sludge Processes. In Biological Treatment Processes. Handbook of Environmental Engineering; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sustarsic, M. Wastewater Treatment: Understanding the Activated Sludge Process. Chem. Eng. Prog. 2009, 105, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Seviour, R.J.; Seviour, R.J. (Eds.) The Microbiology of Activated Sludge; Kluwer Academic Publishing: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet: Trickling Filters; Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Rusten, B. Wastewater Treatment with Aerated Submerged Biological Filters. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1984, 56, 424–431. [Google Scholar]

- Pawęska, K.; Bawiec, A.; Pulikowski, K. Wastewater Treatment in Submerged Aerated Biofilter under Condition of High Ammonium Concentration. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2017, 24, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, S.; Harun, N.Y.; Sambudi, N.S.; Bilad, M.R.; Abioye, K.J.; Ali, A.; Abdulrahman, A. A Review of Rotating Biological Contactors for Wastewater Treatment. Water 2023, 15, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassard, F.; Biddle, J.; Cartmell, E.; Jefferson, B.; Tyrrel, S.; Stephenson, T. Rotating Biological Contactors for Wastewater Treatment—A Review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2015, 94, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment. Water 2010, 2, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment: Five Decades of Experience. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Hu, Z.; Liang, S.; Fan, J.; Liu, H. A Review on the Sustainability of Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment: Design and Operation. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 175, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collivignarelli, M.; Abbà, A.; Benigna, I.; Sorlini, S.; Torretta, V. Overview of the Main Disinfection Processes for Wastewater and Drinking Water Treatment Plants. Sustainability 2017, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M.; Abbà, A.; Alloisio, G.; Gozio, E.; Benigna, I. Disinfection in Wastewater Treatment Plants: Evaluation of Effectiveness and Acute Toxicity Effects. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K. Ultraviolet Disinfection Application to a Wastewater Treatment Plant. Clean Prod. Process. 2001, 3, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Camargo Valero, M.A.; Mara, D.D. Maturation Ponds, Rock Filters and Reedbeds in the UK: Statistical Analysis of Winter Performance. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 55, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuntsho, S.; Shon, H.K.; Vigneswaran, S.; Kandasamy, J. Wastewater Stabilization Ponds (WSP) for Wastewater treatment. In Water and Wastewater Treatment Technologies. Encyclopedia of Life Support System; UNESCO: Oxford, UK, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoli, C.V.; Von Sperling, M.; Fernandes, F. Sludge Treatment and Disposal; Biological Wastewater Treatment Series; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kacprzak, M.; Neczaj, E.; Fijałkowski, K.; Grobelak, A.; Grosser, A.; Worwag, M.; Rorat, A.; Brattebo, H.; Almås, Å.; Singh, B.R. Sewage Sludge Disposal Strategies for Sustainable Development. Environ. Res. 2017, 156, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, O.; Kuehn, V.; Zessner, M. Sludge Management of Small Water and Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 48, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senfter, T.; Fritsch, L.; Berger, M.; Kofler, T.; Mayerl, C.; Pillei, M.; Kraxner, M. Sludge Thickening in a Wastewater Treatment Plant Using a Modified Hydrocyclone. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2021, 4, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makisha, N.; Semenova, D. Production of Biogas at Wastewater Treatment Plants and Its Further Application. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 144, 04016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, N. Sustainable Biogas Production in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants; IEA Bioenergy: Massongex, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M. Wastewater Treatment and Biogas Production: Innovative Technologies, Research and Development Directions. Energies 2022, 15, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasino, N.; Mussati, M.C.; Scenna, N. Wastewater Treatment Plant Synthesis and Design. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 7497–7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, H.H. Biological Wastewater Treatment Processes I: Activated Sludge; Continuing Education and Development, Inc.: Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA; Available online: https://www.cedengineering.com/userfiles/Biological%20Wastewater%20Treatment%20I%20-%20Activated%20Sludge%20R1.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Scholz, M. Activated Sludge Processes. In Wetlands for Water Pollution Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-J.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y. Energy Self-Sufficient Biological Municipal Wastewater Reclamation: Present Status, Challenges and Solutions Forward. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 269, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.; Wu, J.; Qi, L.; Niu, Q. Energy Intensity of Wastewater Treatment Plants and Influencing Factors in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 670, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijns, J.; Hofman, J.; Nederlof, M. The Potential of (Waste)Water as Energy Carrier. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 65, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, V.G. Energy and Water Autarky of Wastewater Treatment and Power Generation Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, H.; Ersahin, M.E.; Dereli, R.K.; Ozgun, H.; Isik, I.; Ozturk, I. Energy Recovery Potential of Anaerobic Digestion of Excess Sludge from High-Rate Activated Sludge Systems Co-Treating Municipal Wastewater and Food Waste. Energy 2019, 172, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, C.; Shi, X.; Sun, J.; Cunningham, J.A. Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants Coupled with Electrochemical, Biological and Bio-Electrochemical Technologies: Opportunities and Challenge toward Energy Self-Sufficiency. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehabi, A.; Stokes, J.R.; Horvath, A. Energy and Air Emission Implications of a Decentralized Wastewater System. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalkhali, M.; Mo, W. The Energy Implication of Climate Change on Urban Wastewater Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 121905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holenda, B.; Domokos, E.; Rédey, Á.; Fazakas, J. Aeration Optimization of a Wastewater Treatment Plant Using Genetic Algorithm. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 2007, 28, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, A.; Verma, A.; Yang, K.; Mejabi, B. Wastewater Treatment Aeration Process Optimization: A Data Mining Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzooei, S.; Miranda, G.H.B.; Abolfathi, S.; Scibilia, G.; Meucci, L.; Zanetti, M.C. Application of Unsupervised Learning and Process Simulation for Energy Optimization of a WWTP under Various Weather Conditions. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 81, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamais, D.; Noutsopoulos, C.; Dimopoulou, A.; Stasinakis, A.; Lekkas, T.D. Wastewater Treatment Process Impact on Energy Savings and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 71, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.; Rocher, V. Energy Consumption Reduction in a Waste Water Treatment Plant. Water Pract. Technol. 2017, 12, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis@Aziz, N.F.; Ramli, N.A.; Hamid, M.F.A. Energy Efficiency of Wastewater Treatment Plant through Aeration System. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 156, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiter, M.; Güell, D.; Comas, J.; Colprim, J.; Poch, M.; Rodríguez-Roda, I. Energy Saving in a Wastewater Treatment Process: An Application of Fuzzy Logic Control. Environ. Technol. 2005, 26, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adibimanesh, B.; Polesek-Karczewska, S.; Bagherzadeh, F.; Szczuko, P.; Shafighfard, T. Energy Consumption Optimization in Wastewater Treatment Plants: Machine Learning for Monitoring Incineration of Sewage Sludge. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, G.; Fernández, B.; Bonmatí, A. Significance of Anaerobic Digestion as a Source of Clean Energy in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 101, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, K.; Tang, W.Z.; Sillanpää, M. Unit Energy Consumption as Benchmark to Select Energy Positive Retrofitting Strategies for Finnish Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs): A Case Study of Mikkeli WWTP. Environ. Process. 2018, 5, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, J.; Hallett, K.; DeWolfe, J.; Venner, I. Energy Efficiency Strategies for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Facilities; NREL/TP-7A20-53341; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2012; p. 1036045. [CrossRef]

- Descoins, N.; Deleris, S.; Lestienne, R.; Trouvé, E.; Maréchal, F. Energy Efficiency in Waste Water Treatments Plants: Optimization of Activated Sludge Process Coupled with Anaerobic Digestion. Energy 2012, 41, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.Y.; Abel, S. Optimization of WWTP Aeration Process Upgrades for Energy Efficiency. Water Pract. Technol. 2011, 6, wpt2011024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Kusiak, A. Minimizing Pump Energy in a Wastewater Processing Plant. Energy 2012, 47, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregrossa, D.; Hansen, J.; Hernández-Sancho, F.; Cornelissen, A.; Schutz, G.; Leopold, U. A Data-Driven Methodology to Support Pump Performance Analysis and Energy Efficiency Optimization in Waste Water Treatment Plants. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloir, C.; Stanford, C.; Soares, A. Energy Benchmarking in Wastewater Treatment Plants: The Importance of Site Operation and Layout. Environ. Technol. 2015, 36, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, J.; Remiszewska-Skwarek, A.; Duda, S.; Łagód, G. Aeration Process in Bioreactors as the Main Energy Consumer in a Wastewater Treatment Plant. Review of Solutions and Methods of Process Optimization. Processes 2019, 7, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, W.A.M.; Helal, A.A.; Abdel Wahab, M.G. Minimizing Energy Consumption in Wastewater Treatment Plants. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Renewable Energies for Developing Countries (REDEC), Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon, 13–15 July 2016; IEEE: Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon, 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Várhelyi, M.; Cristea, V.M.; Luca, A.V. Reducing Energy Costs of the Wastewater Treatment Plant by Improved Scheduling of the Periodic Influent Load. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 262, 110294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, N.; Khatri, K.K.; Sharma, A. Enhanced Energy Saving in Wastewater Treatment Plant Using Dissolved Oxygen Control and Hydrocyclone. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 18, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Esfahani, I.J.; Ifaei, P.; Moya, W.; Yoo, C. Thermo-Environ-Economic Modeling and Optimization of an Integrated Wastewater Treatment Plant with a Combined Heat and Power Generation System. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 142, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qandil, M.D.; Abbas, A.I.; Salem, A.R.; Abdelhadi, A.I.; Hasan, A.; Nourin, F.N.; Abousabae, M.; Selim, O.M.; Espindola, J.; Amano, R.S. Net Zero Energy Model for Wastewater Treatment Plants. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2021, 143, 122101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenicek, P.; Kutil, J.; Benes, O.; Todt, V.; Zabranska, J.; Dohanyos, M. Energy Self-Sufficient Sewage Wastewater Treatment Plants: Is Optimized Anaerobic Sludge Digestion the Key? Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 68, 1739–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano Avilés, A.B.; Del Cerro Velázquez, F.; Llorens Pascual Del Riquelme, M. Methodology for Energy Optimization in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Phase II: Reduction of Air Requirements and Redesign of the Biological Aeration Installation. Water 2020, 12, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano Avilés, A.B.; Del Cerro Velázquez, F.; Llorens Pascual Del Riquelme, M. Methodology for Energy Optimization in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Phase I: Control of the Best Operating Conditions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, C.A.; Andrei, H. Optimization of Energy Consumption of a Wastewater Treatment Plant by Using Technological Forecasts and Green Energy. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering (EEEIC), Florence, Italy, 7–10 June 2016; IEEE: Florence, Italy, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzooei, S.; Campo, G.; Cerutti, A.; Meucci, L.; Panepinto, D.; Ravina, M.; Riggio, V.; Ruffino, B.; Scibilia, G.; Zanetti, M. Optimization of the Wastewater Treatment Plant: From Energy Saving to Environmental Impact Mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zou, Z.; Wang, L. Analysis and Forecasting of the Energy Consumption in Wastewater Treatment Plant. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8690898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Fujimoto, H.; Yamashina, K. Operational Improvement of Main Pumps for Energy-Saving in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water 2019, 11, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gussem, K.; Fenu, A.; Wambecq, T.; Weemaes, M. Energy Saving on Wastewater Treatment Plants through Improved Online Control: Case Study Wastewater Treatment Plant Antwerp-South. Water Sci. Technol. 2014, 69, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, C.S.K.; Behera, A.K.; Dehuri, S.; Cho, S.-B. Radial Basis Function Neural Networks: A Topical State-of-the-Artsurvey. Open Comput. Sci. 2016, 6, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-Y.; Wang, X.-M.; Liu, H.-Q.; Yu, H.-Q.; Li, W.-W. Optimizing Operation of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in China: The Remaining Barriers and Future Implications. Environ. Int. 2019, 129, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforidou, P.; Bariamis, G.; Iosifidou, M.; Nikolaidou, E.; Samaras, P. Energy Benchmarking and Optimization of Wastewater Treatment Plants in Greece. In Proceedings of the 4th EWaS International Conference: Valuing the Water, Carbon, Ecological Footprints of Human Activities, Online, 24–27 June 2020; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; p. 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siatou, A.; Manali, A.; Gikas, P. Energy Consumption and Internal Distribution in Activated Sludge Wastewater Treatment Plants of Greece. Water 2020, 12, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erguvan, M.; MacPhee, D.W. Can a Wastewater Treatment Plant Power Itself? Results from a Novel Biokinetic-Thermodynamic Analysis. J 2021, 4, 614–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, S.; d’Antoni, B.M.; Bongards, M.; Chaparro, A.; Cronrath, A.; Fatone, F.; Lema, J.M.; Mauricio-Iglesias, M.; Soares, A.; Hospido, A. Monitoring and Diagnosis of Energy Consumption in Wastewater Treatment Plants. A State of the Art and Proposals for Improvement. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 1251–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, P.; Wang, H.; Robinson, Z.P.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Li, F. The Feasibility and Challenges of Energy Self-Sufficient Wastewater Treatment Plants. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Li, F. Energy Self-Sufficient Wastewater Treatment Plants: Feasibilities and Challenges. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 3741–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maktabifard, M.; Zaborowska, E.; Makinia, J. Achieving Energy Neutrality in Wastewater Treatment Plants through Energy Savings and Enhancing Renewable Energy Production. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 17, 655–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maktabifard, M.; Al-Hazmi, H.E.; Szulc, P.; Mousavizadegan, M.; Xu, X.; Zaborowska, E.; Li, X.; Mąkinia, J. Net-Zero Carbon Condition in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Systematic Review of Mitigation Strategies and Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keywords/Phrases | Number of References |

|---|---|

| Treatment stages of wastewater | 33 |

| Aeration energy optimization in WWTPs | 22 |

| Secondary treatment | 22 |

| Activated sludge treatment | 18 |

| Sustainable WWT practices | 16 |

| Energy recovery in WWT | 16 |

| Tertiary treatment in WWTPs | 15 |

| Energy-saving techniques in WWTPs | 14 |

| Energy optimization in WWT | 12 |

| Energy consumption at different stages of process | 12 |

| Renewable energy in WWTPs | 12 |

| Process optimization in WWTPs | 11 |

| Data-driven approaches for energy saving in WWTPs | 11 |

| Stage of sludge treatment | 10 |

| Carbon footprint reduction in WWTPs | 9 |

| Energy consumption reduction in WWTPs | 8 |

| Energy audit in WWTPs | 8 |

| Anaerobic treatment | 7 |

| Operational strategies for energy efficiency in WWTPs | 7 |

| Aerobic process | 5 |

| Biogas production during digestion | 4 |

| Preliminary treatment | 4 |

| Primary treatment | 3 |

| Treatment Level (1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Object | Preliminary | Primary | Secondary |

| Pollutants eliminated | Coarse solids | Settleable solids Particulate BOD * | Non-settleable solids Fine particulate BOD * Soluble BOD * Nutrients (3) Pathogens (3) |

| Treatment effectiveness | – | SS **: 60–70% BOD *: 25–40% Coliforms: 30–40% | SS **: 65–95% BOD *: 60–99% Coliforms: 60–99% (4) |

| Predominant treatment mechanism | Physical | Physical | Biological |

| Complies with usual discharge standards (2) | No | No | Generally, yes |

| Implementation | Upstream of pumping stations Initial treatment stage | Partial treatment Intermediate stage of a more complete treatment | More comprehensive treatment (for organic matter) |

| Stabilization Ponds [24,25,26,27] | |

| Facultative pond | Wastewater flows continuously through a purpose-built pond, where aerobic stabilization of soluble and fine particulate BOD occurs due to dispersed bacteria. Algae aid in oxygen provision through photosynthesis, but extensive land usage is required. |

| Anaerobic pond–facultative pond | Approximately 50 to 65% of BOD is converted in the deeper, smaller-volume anaerobic pond, with the remaining BOD eliminated in the facultative pond, requiring less space than a single facultative pond. |

| Facultative aerated lagoon | Like a facultative pond, but mechanical aerators provide oxygen instead of relying on photosynthesis. Despite aeration, settling of sewage solids and biomass occurs, decomposing anaerobically at the pond bottom. |

| Completely mixed aerated lagoon sedimentation pond | Thorough mixing keeps solids dispersed, enhancing BOD removal efficiency. Effluent contains elevated solids levels, necessitating removal before discharge into the receiving body, facilitated by a sedimentation pond. |

| High-rate ponds | Engineered to maximize algal production in a fully aerobic environment, with shallower depths allowing extensive light penetration, promoting photosynthetic activity and elevated oxygen levels. Moderate agitation is induced by low-power mechanical equipment. |

| Maturation ponds | Designed to eradicate pathogenic organisms by establishing unfavorable environmental conditions, such as exposure to UV radiation, high pH levels, abundant oxygen, lower temperatures, nutrient scarcity, and predation by other organisms. They serve as a post-treatment phase, demonstrating exceptional efficiency in removing coliforms. |

| Land Disposal [28,29,30,31] | |

| Slow-rate system | Involve dispersing wastewater onto the soil, aiming for either treatment or water reuse for agriculture or landscaping. Plants absorb liquid efficiently, even with minimal application on their surfaces. Various distribution methods are used, including sprinklers and drip irrigation. |

| Rapid infiltration | Distribute wastewater over shallow basins, allowing it to seep into the soil. Evaporation losses are minimized, and vegetation may or may not be cultivated. Application is intermittent, with options like groundwater recharge and underdrain recovery. |

| Subsurface infiltration | Involves introducing pre-treated sewage beneath the soil surface, often from septic tanks. Infiltration trenches or chambers aid conveyance and partial treatment before infiltration. |

| Overland flow | Overland flow systems disperse wastewater across vegetated slopes, with treatment occurring within the root–soil system. Distribution methods include sprinklers and pipes, with sporadic application. |

| Constructed wetlands | They are aquatic-based systems with shallow basins or channels supporting aquatic plants. Processes occur within the root–soil system, with options for free-water surface or subsurface flow configurations. |

| Anaerobic Systems [32,33,34,35,36,37,38] | |

| Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor (UASB) | Employs anaerobic conversion of BOD by dispersed bacteria, with liquid flowing upwards. Methane is produced, and the reactor includes settling and gas collection zones. Minimal sludge production occurs, and excess sludge is already thickened and stabilized. |

| Anaerobic filter | In the anaerobic filter, organic pollutants are transformed by bacteria attached to a support medium within the submerged tank. A primary sedimentation tank is required, but sludge production remains minimal. |

| Anaerobic reactor–post-treatment | Anaerobic reactors often require post-treatment to meet discharge standards. This can involve biological or physical–chemical methods, with overall efficiency comparable to untreated wastewater but with reduced land, volume, and energy requirements, as well as lower sludge production levels. |

| Activated Sludge [39,40,41,42,43] | |

| Conventional activated sludge | Conventional activated sludge involves an aeration tank and a secondary sedimentation tank. Biomass is recirculated to maintain high concentrations for effective BOD removal. Excess sludge is treated for stabilization. Oxygen is introduced through mechanical aerators or diffused air. |

| Activated sludge (extended aeration) | Extended aeration extends the retention time of biomass, reducing substrate availability and promoting self-maintenance. Excess sludge is already stabilized, and primary sedimentation tanks are typically omitted. |

| Intermittently operated activated sludge (sequencing batch reactors) | Sequencing batch reactors operate intermittently, cycling between aerated and settling stages within one tank. Secondary sedimentation tanks are not needed, and the system can function in conventional or extended aeration modes. |

| Activated sludge with biological nitrogen removal | Includes an anoxic zone where nitrates serve as a respiratory substrate for microorganisms, reducing them to gaseous nitrogen. |

| Activated sludge with biological nitrogen and phosphorus removal | Activated sludge, featuring biological nitrogen and phosphorus removal capabilities, incorporates aerobic, anoxic, and anaerobic zones. Microorganisms absorb excess phosphorus, which is effectively removed with excess sludge. |

| Aerobic Biofilm Reactors [44,45,46,47,48] | |

| Low-rate trickling filter | Low-rate trickling filters facilitate aerobic stabilization of organic pollutants with bacteria adhering to support media. Sewage is distributed onto the tank’s surface, filtering through the medium as bacteria degrade organic matter. Sludge dislodged from the medium is removed in a secondary sedimentation tank, and primary sedimentation is essential for effective operation. |

| High-rate trickling filter | High-rate trickling filters handle higher BOD loads, requiring sludge stabilization during treatment. Effluent recirculation to the filter dilutes influent and ensures consistent hydraulic load. |

| Submerged aerated biofilter | Submerged aerated biofilters contain porous material through which sewage and air flow continuously. Air moves upwards while liquid flow can be upward or downward. Granular material acts as a support and filter medium, removing soluble organic compounds and particulate matter. Periodic backwashings remove excess biomass, reducing head loss. |

| Rotating biological contactor (biodisc) | The biomass attaches to a support medium, typically consisting of a series of discs. These discs, partially submerged in the liquid, rotate and alternate between exposure to the liquid and air as they rotate. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Optimization challenges in the alternating activated sludge process. | Achieve a 10% reduction in pollution load. | [75] |

| 2017 | A data-driven approach for modeling and optimizing the aeration process in a large-scale WWTP in the Midwest. | Achieve a 31.4% decrease in energy consumption for aeration through oxygen reduction, while maintaining the effluent water quality in accordance with the standard requirements. | [76] |

| 2020 | Employing a hybrid modeling approach to streamline weather-dependent operations and optimize energy consumption at Italy’s largest WWTP. | Aeration energy consumption could be reduced from 4.1% to 6.8%. | [77] |

| 2015 | A model was implemented in 10 WWTPs in Greece to assess their carbon footprint. Based on these findings, energy-saving strategies were proposed to reduce both energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. | At the Psyttalia WWTP, implementing different DO scenarios results in a reduction ranging from 6% to 10.1%. For substantial energy savings of around 11.2%, an approach that considers both DO values and sludge age can be employed, potentially leading to energy savings of approximately 4500 MWh per year. | [78] |

| n.d * | An extensive optimization experiment was conducted to refine DO control in the aerobic tanks at the Käppala WWTP in Stockholm, Sweden. | The overall outcome resulted in a notable 18% decrease in total airflow, while maintaining treatment efficiency. | [7] |

| 2017 | The Syndicat Interdépartemental pour l’Assainissement de l’Agglomération Parisienne, an operator in the Paris metropolitan area, has implemented initiatives to optimize energy consumption. | By reducing the injected air flows, starting at 8 Nm3 h−1 and gradually decreasing to 6.5, and then 4 Nm3 h−1, the estimated energy consumption reduction in 2013 was approximately 0.7 MWh per ton of removed nitrogen. This estimation is based on an energy consumption rate of 0.033 kWh Nm−3 of produced air. | [79] |

| 2019 | Investigate strategies to improve energy efficiency at a WWTP in Malaysia focusing on the aeration tank. Assess the energy savings from implementing High-Speed Turbo compressors compared to roots blowers. | Achieving a reduction in energy consumption by up to 42% would result in a return on capital expenditure which would be achieved within 1.22 years. | [80] |

| 2005 | Develop and implement a fuzzy logic controller to regulate aeration at the Taradell WWTP. The goal is to conserve energy while maintaining effluent quality by integrating data from DO and oxidation-reduction potential signals from the fuzzy controller. | The implementation results in energy savings of over 10%, ensuring that effluent quality is not compromised. | [81] |

| Reference | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [75] | Incorporating genetic algorithm. | Investigation into the effects of frequent aeration switching, including its impact on aerator lifespan. |

| [76] | Implementing a data-mining algorithm for optimizing the aeration process. | Development of models with increased frequency of data collection. |

| [77] | Optimizing energy usage based on weather conditions. | Broader exploration of factors beyond weather. |

| [78] | An evaluation of energy consumption and carbon footprint across 10 WWTPs in Greece, accompanied by recommendations for efficiency improvements and savings. | Assessment of energy consumption and carbon footprint across multiple WWTPs in Greece, considering their applicability to other plants. |

| [7] | Implementation of individual control in aeration zones. | Adoption of individual control in aeration zones, with a more comprehensive analysis of associated costs. |

| [79] | Creation and execution of targeted energy-saving techniques designed to decrease total energy usage. | Development and application of targeted energy-saving techniques to reduce overall energy usage, with a focus on evaluating their long-term performance. |

| [80] | Deploying of High-Speed Turbo compressors. | Implementation of High-Speed Turbo compressors, recognizing potential limitations to their applicability based on plant scale and operational conditions. |

| [81] | Development and applying a fuzzy logic controller for aeration regulation. | Design and execution of a fuzzy logic controller for aeration regulation, with consideration of challenges related to data accuracy and algorithm complexity. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Reduction in energy consumption of Autothermal Thermophilic Aerobic Digestion (ATAD). | Achieved a 22% decrease in single-stage ATAD and an 18% reduction in two-stage ATAD. | [4] |

| 2023 | Development of a simulation-based methodology for energy saving in a sludge incineration unit, utilizing data from the WWTP in Gdynia, Poland. | Resulting in a 6% reduction in overall energy consumption for the incineration unit. | [82] |

| 2008 | Solid waste management through plasma gasification at the Psyttalia WWTP, Athens, Greece. | Demonstrated energy self-sufficiency and generated 2.85 MW of electrical energy. | [8] |

| 2015 | Study conducted on five WWTPs in Catalonia. | Highlighted anaerobic digestion as a promising technology for extracting energy from wastewater, emphasizing the need for implementing strategies to optimize biogas production. | [83] |

| 2016 | Examination of energy production, usage, and conservation at Ringsend WWTP in Ireland, including improved biosolids management. | Achieving savings up to 75% in electrical energy consumption. | [10] |

| Reference | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [4] | Focus on optimizing energy usage in ATAD processes. | Further research needed on responses to unusual sludge compositions. |

| [82] | Creation of methodologies for energy savings in sludge incineration. | Further research needed on the applicability and transferability to other WWTPs. |

| [8] | Comprehensive strategy integrating sludge treatment and electricity generation. | Further research needed on the analysis of economic aspects and scalability. |

| [83] | Highlights the importance of biogas utilization. | Further research needed on the increase in biogas production. |

| [10] | Significant electricity savings and a forward-thinking goal of achieving energy neutrality, providing a model for other plants. | The feasibility of improved biosolids management and other technical strategies may depend on existing infrastructure and technology readiness, necessitating further exploration. Additionally, a detailed cost–benefit analysis is proposed, along with addressing the practical challenges and costs associated with large-scale implementation. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Introduction of a statistical analysis method for unit energy consumption in conventional Finnish WWTPs. | Potential maximum energy savings could reach as high as 1.26 kWh kg−1 COD. | [84] |

| 2012 | Conducting an energy audit covering influent pumping, the aeration process, UV disinfection, and solids handling at Crested Butte WWTP of Colorado. | Presents best practices for facility managers to readily adopt and achieve energy efficiency. | [85] |

| 2012 | Optimization of a WWT process, focusing on carbon and nitrogen removal. | Utilizes model-based analysis to enhance energy efficiency in WWT. | [86] |

| 2011 | Integration of turbo blowers as a replacement for conventional blowers in WWTPs. | Demonstrative trials were conducted at two WWTPs, Franklin in New Hampshire and the Central Advanced in Fort Myers, Florida. Estimated to result in an 32% and 17% reduction in energy consumption, respectively, demonstrating the significant potential for energy savings with this technology. | [87] |

| Reference | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [84] | Analysis of energy consumption in Finnish WWTPs provides valuable insights into current energy usage patterns and potential areas for optimization | Careful consideration required for practical implementation of proposed technologies could lead to improved energy efficiency and reduced operational costs. |

| [85] | A detailed analysis conducted in Crested Butte, Colorado, focusing on energy conservation strategies offers a thorough examination of specific measures to reduce energy consumption in WWT. | Consideration should be given to the potential challenges associated with adapting the findings to various environmental contexts. |

| [86] | In-depth examination of carbon and nitrogen removal processes. | Addressing limited consideration of economic and thermal factors in carbon and nitrogen removal processes could enhance the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of WWT methods. |

| [87] | The study confirms the potential for significant energy savings with the adoption of turbo blowers in WWTPs, highlighting a promising technological solution for energy efficiency. | Detailed cost–benefit analyses, including initial investment costs and long-term maintenance considerations, could inform decision-making processes and maximize the potential benefits of adopting turbo blowers in WWTPs. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011, 2012 | Development of a framework for modeling variable-speed pumps in the preliminary WWT process. | Utilizing data-driven approaches for pump modeling. | [1,88] |

| 2017 | Creation of an innovative data-driven methodology aimed at holistically assessing pump systems. | Differentiating between long-term and short-term phenomena. Developing a user-friendly performance index. Early detection of potential issues. Extracting valuable insights from data. Suggesting economically feasible solutions. | [89] |

| Authors | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [1,88] | Development and application of data-mining algorithm to model pump operations. | Investigation into potential limitations under various operating conditions. |

| [89] | Development of innovative data- driven methodologies for evaluating pump systems. | Further validation and implementation in diverse operating environments. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Conduct a comprehensive energy benchmarking analysis on two full-scale WWTPs utilizing oxidation ditches as the primary treatment process to determine an optimal solution for site optimization. | Reduction of 55% in BOD reaching the oxidation ditch. Reduction of 75% in TSS reaching the oxidation ditch. Reduction of 12% in NH4 reaching the oxidation ditch. Aeration requirements reduced by 49% kWh d−1 Significant decrease in greenhouse gas emissions: from 1510 kg of CO2 equivalent per day to 415 kg of CO2 equivalent per day. | [90] |

| 2019 | Examine the design and categorization of aeration systems, with a focus on critical parameters and factors that impact the aeration process, including oxygen transfer efficiency, diffuser fouling, strategies for mitigating fouling, and the selection of appropriate diffusers. | Fine-bubble diffuser systems are identified as highly efficient in Polish WWTPs. Maintaining the condition and efficiency of these systems is crucial. Concerns raised regarding the energy intensity of the aeration process. | [91] |

| 2016 | Assess the potential for energy reduction through the implementation of variable-speed drives and energy-efficient motors at Alexandria East WWTP. | Integration of variable-speed drives resulted in an average annual energy savings of 15,804.5 kWh. Implementation of energy-efficient motors led to an average annual energy savings of 2628 kWh. | [92] |

| 2017 | Investigate the selection and optimization of turbine designs in four WWTPs in Ireland. | Optimized system efficiencies at different sites range from 73% to 76%. Turbine costs vary from EUR 315 to 1708 per kW depending on the type. Utilizing pump-as-turbines results in system efficiencies of 58–62%. Incorporating two pump-as-turbines in parallel further improves efficiency by an additional 5%. | [2] |

| 2020 | Repurpose existing WWTP tank infrastructure to partially store wastewater during the day and schedule purification processes for nighttime in a Romanian WWTP with an anaerobic-anoxic-oxic process configuration. | Operational costs reduced by 47%. Effluent quality improved by 25%. Aeration energy reduced by 36.7%. Increase in total pumping energy. Overall operational energy decreased due to the significant reduction in aeration energy. | [93] |

| 2020 | Improve primary sludge separation through hydrocycloning at a WWTP in Jaipur, India, which utilizes the biological-activated sludge process. | Installation of VFDs resulted in 17.15% improvement in power factor; 17.48% increase in energy efficiency. Implementation of VFDs and PLC-based PID Controllers for DO set-point in the bioreactor led to a 65.74% reduction in aeration energy consumption. Integration of hydrocyclones with smart aeration control achieved a 71.46% decrease in aeration energy requirements. | [94] |

| Reference | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [90] | Comparison of energy consumption between two different plants with recommendations for optimization. | Further research needed to assess the economic viability of proposed solutions. |

| [91] | Approach aimed at controlling proper aeration and reducing energy consumption in a WWTP in Poland. | Explore the application of controls to other facilities for broader impact. |

| [92] | Application of technological solutions to reduce energy consumption across large-scale operations. | Future studies should include comprehensive monitoring to evaluate the efficiency of implemented measures. |

| [2] | Creation of optimal technological solutions tailored to increase energy efficiency within 4 WWTPs in Ireland. | Validate and certify proposed methodology through further research in diverse operational settings. |

| [93] | Strategy to leverage current plant infrastructure to reduce operating costs and enhance effluent quality. | Investigate the impact of the strategy in different settings through additional research and evaluation. |

| [94] | Aim to enhance primary sludge separation through hydrocycloning, potentially improving overall treatment efficiency. | Future research should replicate experimental investigations across multiple WWTPs to generalize results. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Investigating the energy consumption of the WWTP in Rzeszów. | The energy generated from biogas meets 74.3% of the electrical and 95.5% of the heat requirements compared to the total energy consumption. | [6] |

| 2017 | Introducing an optimal design approach to maximize the sustainability of an integrated WWTP equipped with a Combined Heat and Power (CHP) unit. | Optimization results demonstrate a 16.9% reduction in total cost rates and a 5.3% decrease in environmental impacts. The power generated by the optimized system can fulfill 47% of the WWTP’s power demand while meeting the entire heat requirement. | [95] |

| 2021 | Exploring scenarios of high penetration of renewable energy sources in WWTPs using dynamic simulation and optimization. | Highly renewable wastewater systems provide flexibility services to power and heating networks, along with benefits such as heat production and improved effluent quality suitable for various applications. | [5] |

| 2020 | Presenting an approach to design solar Photovoltaic (PV) systems to minimize energy consumption in aeration processes. | This approach assists the industry in making decisions regarding PV investments, supporting wastewater utilities in embracing sustainable management practices. Consequently, it advances the integration of renewable energy sources within the wastewater sector. | [3] |

| 2021 | Recommending a series of energy efficiency measures including CHP, PV systems, and hydroelectric power. | Achieved a total energy savings of 71%. | [96] |

| 2015 | Investigating key strategies to optimize the energy balance in two advanced municipal WWTPs (Wolfgangsee-Ischl and Strass WWTPs) with nutrient removal. | Implementation of additional strategies, such as incorporating organic waste into digesters through co-digestion, harnessing thermal energy from wastewater for space heating, and exploring innovative processes for wastewater and waste management, holds the promise of transforming municipal wastewater systems into “energy-positive” entities. | [9] |

| 2013 | Optimizing biogas production at Prague’s Central WWTP through various strategies. | Increased biogas production to 12.5 m3 per population equivalent per year resulted in a rise in specific energy production from approximately 15 to 23.5 KWh per population equivalent per year. | [97] |

| Reference | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [6] | Achieving high levels of energy self-sufficiency through anaerobic digestion technology. | Research on optimizing performance under diverse operating conditions. |

| [95] | Creation of optimized designs ensuring the highest sustainability for WWTPs. | Further development and testing to refine and validate the proposed designs. |

| [5] | Considering high rates of renewable energy for designing self-sufficient systems. | Exploring strategies to overcome implementation barriers for broader adoption. |

| [3] | Introducing an innovative methodology for designing solar photovoltaic systems for WWTPs. | Conducting extensive field trials to validate and enhance the methodology for practical use. |

| [96] | Proposing a flexible energy-saving system with high potential for savings. | Expanding financial analyses to include diverse regional markets and conditions. |

| [9] | Implementing combined measures for energy self-sufficiency. | Investigating the long-term environmental and social impacts of combined measures. |

| [97] | Integrating strategies to improve biogas production. | Developing comprehensive models to assess constraints and optimize cost-efficiency. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019, 2020 | Flow modeling, simulation techniques, measurement of air transfer efficiency, and redesigning the aeration facility at the San Pedro del Pinatar WWTP. | Energy consumption reduction exceeding 20%. | [98,99] |

| Reference | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [98,99] | Presentation of a strategy aimed at enhancing the operation of the aeration equipment, leading to decreased energy consumption. | Further verification of the effectiveness of the measures under various operating conditions. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Develop an energy optimization strategy focused on green energy. | Proposed a methodology that engineers can use to predict energy consumption throughout the WWTP lifecycle. | [100] |

| 2019 | Introduce a simulation-based approach to establish a comprehensive link between treatment processes and energy demand/production. | Identified potential energy savings of up to 5000 MWh annually, along with improved effluent quality. | [101] |

| 2019 | Apply fuzzy clustering to investigate the relationship between energy consumption and its influencing factors. Evaluate the performance of RBF model vs. multi-variable linear regression. | Results provide a crucial theoretical foundation for energy conservation efforts in WWTPs. | [102] |

| 2019 | Analyze operational simulation results for four cases to identify energy-efficient operational methods and opportunities to optimize power consumption at a Japanese WWTP. | Demonstrated potential for 10% reduction in energy consumption. | [103] |

| 2014 | Demonstrate how activated sludge modeling and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) can be used to optimize energy consumption in WWTPs. | Achieved energy savings ranging from 1.3% to 3.3%. | [104] |

| Reference | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [100] | Ιnnovative approach that considers different scenarios and uses both linear and logistic growth models to estimate energy consumption. | Applying and validating the methodology in WWTPs of varying scales to ensure its practical applicability. |

| [101] | Comprehensive approach to optimizing energy consumption at Italy’s largest WWTP. | Opportunity to further assess the methodology’s effectiveness and apply it to additional WWTP sites. |

| [102] | Use of fuzzy clustering and neural networks for forecasting energy consumption. | Discussing and demonstrating the real-world application and validation of the proposed approach. |

| [103] | Demonstrated potential for a 10% reduction in power consumption by adopting energy-efficient operational methods, highlighting the feasibility of sustainable practices in WWTPs. | Evaluating the generalizability of the findings to other WWTPs with different configurations or operational conditions. |

| [104] | Demonstrated the potential of activated sludge modeling and CFD to optimize energy consumption. | Validating the actual implementation and feasibility of these approaches, while accounting for site-specific factors and resource constraints, to further optimize the energy-saving potential. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | A comprehensive analysis of the current operational status of WWTPs in China. | The study examines potential avenues for improvement to overcome the barriers, providing valuable insights for optimizing municipal wastewater management in China for enhanced efficiency and sustainability. | [106] |

| 2020 | The utility of energy consumption benchmark values as a robust management tool for assessing the optimal energy efficiency of 243 WWTPs across Greece. | Utilizes the current situation of Greek WWTPs and incorporates the most effective techniques to suggest optimized measures aimed at improving their operational efficiency. | [107] |

| 2020 | Examining the energy demands of 17 WWTPs in Greece that utilize the activated sludge method, serving populations ranging from 1100 to 56,000 inhabitants. | The study uncovered significant variations in energy requirements per flow rate or per inhabitant among the surveyed WWTPs, suggesting opportunities for improvements to reduce overall energy consumption. | [108] |

| Reference | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [106] | An analysis of challenges faced by WWTPs in China and potential directions for improvement. | Development and proposal of specific technical solutions to address the identified challenges in Chinese WWTPs. |

| [107] | An examination of statistical data on energy consumption in WWTPs in Greece. | Inadequate discussion on the application of best practices. |

| [108] | A comprehensive analysis of energy requirements in 17 WWTPs in Greece, utilizing the activated sludge method. | Practical implementation of specific optimization proposals to reduce energy consumption in the studied WWTPs. |

| Year | Aim | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | A theoretical thermodynamic study investigating the energy self-sufficiency of a WWTP. | The findings indicate that the proposed system can meet up to 109% of the WWTP’s energy requirements. | [109] |

| Authors | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [109] | Theoretical thermodynamic study on achieving energy self-sufficiency in WWTPs. | Further practical applications. |

| Year | Main Points | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | The Green Bay, Wisconsin Metropolitan Sewerage District reduced electricity consumption by 50%, saving 2,144,000 kWh annually, through the implementation of energy-efficient blowers. In Albert Lea, Minnesota, a WWTP installed a 120 kW microturbine CHP system, saving approximately USD 100,000 annually and reducing energy usage by 70% due to lower electricity, fuel expenses, and maintenance costs. In Switzerland, energy analyses conducted on two-thirds of WWTPs led to an average cost reduction of 38%. A domestic WWTP with aerobic-activated sludge and anaerobic digestion utilizes 0.6 kWh m−3, with over 50% of energy consumption attributed to aeration. Anaerobic digestion biogas can meet 25–50% of energy needs, and additional modifications can further reduce energy requirements. | [70] |

| 2016 | The energy performance of WWTPs cannot be universally characterized by a single Key Performance Indicator (KPI). Several factors significantly influence energy performance, including plant size, dilution factor, and flow rate. Additionally, technology choice, plant layout, and geographical location contribute to the variability in energy performance among WWTPs. These elements collectively lead to the significant differences observed in the energy efficiency of WWTPs. | [110] |

| 2017 | The study offers a comprehensive examination of global energy consumption in WWTPs, delving into diverse technologies and emphasizing the pursuit of energy self-sufficiency. It underscores the significance of international benchmarking to enhance energy efficiency, acknowledging regional disparities stemming from varying technologies and effluent quality targets. Optimal energy efficiency is highlighted as paramount in WWTP design, with many facilities leveraging biogas derived from anaerobic digestion for heating and electricity generation. Additionally, some integrate renewable energy sources into their systems. However, despite the feasibility of these approaches, challenges persist, particularly in developing nations. | [111,112] |

| 2018 | Aeration stands out as the predominant energy consumer in WWTPs, often surpassing 50% of total energy usage. Control systems such as Ammonia vs. Nitrate (AVN) and Ammonia-Based Aeration Control (ABAC) have proven effective in reducing energy consumption, with potential downtime for blowers exceeding 25% while still maintaining effluent standards. Technological advancements, particularly in nitrogen removal pathways, offer the possibility of cutting aeration energy requirements by over 60%. To move towards energy neutrality, WWTPs are increasingly focusing on enhancing on-site energy production through anaerobic digestion and biomethane utilization with CHP engines. Pre-treatment of sludge emerges as a significant opportunity, potentially increasing energy output by up to fivefold. Additional strategies include the co-digestion of organic waste and on-site renewable energy production, with the potential to double biogas production and further contribute to energy self-sufficiency. | [113] |

| 2023 | Optimizing operational parameters, including adjustments to DO levels, Sludge Retention Time (SRT), and Mixed Liquor Recirculation (MLR), can lead to a significant reduction in energy consumption, typically in the range of 7–9%. The implementation of Total Nitrogen (TN) online monitoring at influent and effluent points has been shown to improve TN treatment efficiency by 1%, resulting in a 5.6% reduction in energy consumption and a 12.7% decrease in carbon emissions. Furthermore, upgrading to magnetic suspension centrifugal blowers can yield notable benefits, including a reduction in aeration energy ranging from 15% to 24%, accompanied by a decrease in the carbon footprint by 4.6–7.7%. Utilizing prediction models to forecast energy consumption one month in advance has been shown to lead to a 2.2% reduction in energy usage. Furthermore, co-digestion practices have demonstrated significant benefits: Co-digesting 7% fat with sewage sludge increased biogas output by 17%. Addition of fat-oil-grease (FOG) to low-strength wastewater resulted in a boost in energy production by 0.08 kWh/m3. Incorporating carbonated soft drinks into the digestion process increased biogas production by up to 191%. Introduction of 3% glycerol led to an 81% increase in biogas production. Utilization of grease trap water increased biogas production by up to 209%. | [114] |

| Authors | Strengths | Potential Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| [70] | Thorough examination of energy consumption throughout water supply, WWT, and power generation systems. | Opportunity for further research and practical validation of the proposed strategies. |

| [110] | In-depth coverage of literature on energy efficiency and monitoring methods for WWTPs. | Opportunity to develop specific strategies for achieving energy self-sufficiency. |

| [111,112] | Introduction of alternative strategies for achieving energy self-sufficiency in WWTPs. | Opportunity for additional research and verification in real operating conditions. |

| [113] | Extensive exploration of technologies aimed at reducing energy consumption in WWTPs. | Opportunity to conduct further research to validate the effectiveness of proposed measures under practical circumstances |

| [114] | Comprehensive review of practices aimed at achieving zero greenhouse emissions in WWTPs. | Opportunity to develop specific techniques for achieving zero emissions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsalas, N.; Golfinopoulos, S.K.; Samios, S.; Katsouras, G.; Peroulis, K. Optimization of Energy Consumption in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: An Overview. Energies 2024, 17, 2808. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17122808

Tsalas N, Golfinopoulos SK, Samios S, Katsouras G, Peroulis K. Optimization of Energy Consumption in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: An Overview. Energies. 2024; 17(12):2808. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17122808

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsalas, Nikolaos, Spyridon K. Golfinopoulos, Stylianos Samios, Georgios Katsouras, and Konstantinos Peroulis. 2024. "Optimization of Energy Consumption in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: An Overview" Energies 17, no. 12: 2808. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17122808

APA StyleTsalas, N., Golfinopoulos, S. K., Samios, S., Katsouras, G., & Peroulis, K. (2024). Optimization of Energy Consumption in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: An Overview. Energies, 17(12), 2808. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17122808