1. Introduction

The climate change observed today and predicted for the future has forced EU countries to take action to develop long-term community policies to counteract and adapt to the changes where possible. Central EU-level discussions have led to the conclusion that counteracting or adapting to our changing ecosystem is not only a political issue but also an economic one.

In line with this principle, EU member states have recognised that economic operators, as an indispensable part of the progress of societies and the well-being of humankind, should be environmentally sustainable and should study their impact on the natural environment and the surroundings in which they operate. Key institutions that have a significant impact on the creation and development of businesses are actors in the financial sector.

In March 2018, the European Commission issued the communication “Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth” [

1], which outlined the community’s long-term policy related to reforming the financial system in order for it to become a stimulus for a green transition among economic actors. The EU’s most important objective has become to reorient capital flows towards sustainable investment, managing financial risks stemming from climate change, resource depletion, environmental degradation and social issues as well as fostering transparency and long-termism in financial and economic activity [

1]. The publication of the above document has triggered further transformation of the legal environment around enterprises, in particular financial enterprises, i.e., banks and investment firms, whose activities have a substantial impact on the establishment and development of enterprises. An important element here is the environmental and social cost of business, which until now has not been taken into account in business analyses. In view of these changes, a concept emerged that was intended to become the new, extended Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)—Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) [

2]. The main difference between the two concepts is that ESG explicitly includes the issue of corporate governance, whereas CSR only partially covers it, since the latter concept involves environmental and social issues [

3]. Thus, ESG is a broader term than CSR ([

3], p. 2).

As far as the financial sector is concerned, and in particular the banking and investment sectors, a number of legislative changes and guidelines from EU-level supervisors have been drafted. The aim of these changes is to focus on “green investment” finance; they also impose obligations to integrate the environmental factor into risk management strategies, with a particular focus on credit or operational risk management [

4].

The financial/banking sector is viewed as a key factor in driving companies towards sustainability [

5,

6]. It is financial systems that provide the impetus for sustainable business development and “(…) provide a tool for combating poverty, climate change, social exclusion, or negative externalities” ([

7], p. 2).

Nevertheless, in order to achieve sustainable development through banks, the reorganisation and adaptation of the financial market to its specific conditions is required. In the face of the demands to create new concepts of finance and banking taking into account sustainable development, the concepts of sustainable finance and sustainable banking are being increasingly proposed in the literature [

8]. Thus, the questions of how to create a sustainable financial system and how individual ESG factors should serve as its building blocks need to be answered [

7].

With this context in mind, the main objective of this paper is therefore to identify the current condition of and ongoing developments in the EU legislation on ESG and sustainable finance.

As for the layout of the rest of the paper, the second section of this article presents selected factors that are used for ESG ratings and assessments, with a special focus on financial institutions and non-financial economic operators. This section of the paper also discusses the essence and importance of the role of integrating non-financial criteria into actions, both in the banking sector and among investors, corporate managers, non-banking institutions or other organisations. The third section provides an overview of existing bibliographical references for studies intended to demonstrate correlations between environmental responsibility management activities and firm performance. The fourth section details the materials and describes the methodology used in the present study. The fifth section presents the results of the analysis of EU-level legislation in order to show the factual state of affairs and the ongoing changes in EU legislation since 2018 with respect to sustainable finance. The discussion in the next part of the paper refers to previous empirical studies on non-financial reporting practices used by the Polish banking sector. Thereby, a comparison and summary of experiences regarding inclusion of CSR or ESG criteria by banks in Poland and their level of engagement in actions for sustainable development were made. The final part of the paper contains a summary and conclusions from the analyses performed and recommendations.

2. ESG Factors and Their Significance in the Financial Sector

The activity and initiatives undertaken by financial institutions to protect the environment are now the goal of evolution of the entire financial market ([

9], pp. 173–174). Financial institutions have the capacity to indirectly influence the environment through their impact on companies they finance ([

10], p. 36). It is the banks that hold a leading position in the economy by mobilising large financial resources and are subject to increasing demands of stakeholders. This is why it is important to study the influence of CSR/ESG on banks’ operations [

11,

12].

In the 21st century, investment decisions are increasingly rarely made purely on the basis of financial parameters (e.g., profitability). Currently, there is also a growing recognition of the need to take into account non-financial (ethical) factors, including a sense of responsibility for the economic measures taken, which may be subject to separate analysis against ESG criteria ([

13], p. 87). Sustainability reporting (SR) is already the worldwide orientation for companies to disclose their efforts and activities in addressing ESG criteria [

14]. In view of the foregoing, ESG risk identification and management should cover a variety of aspects that ought to be considered during evaluation (

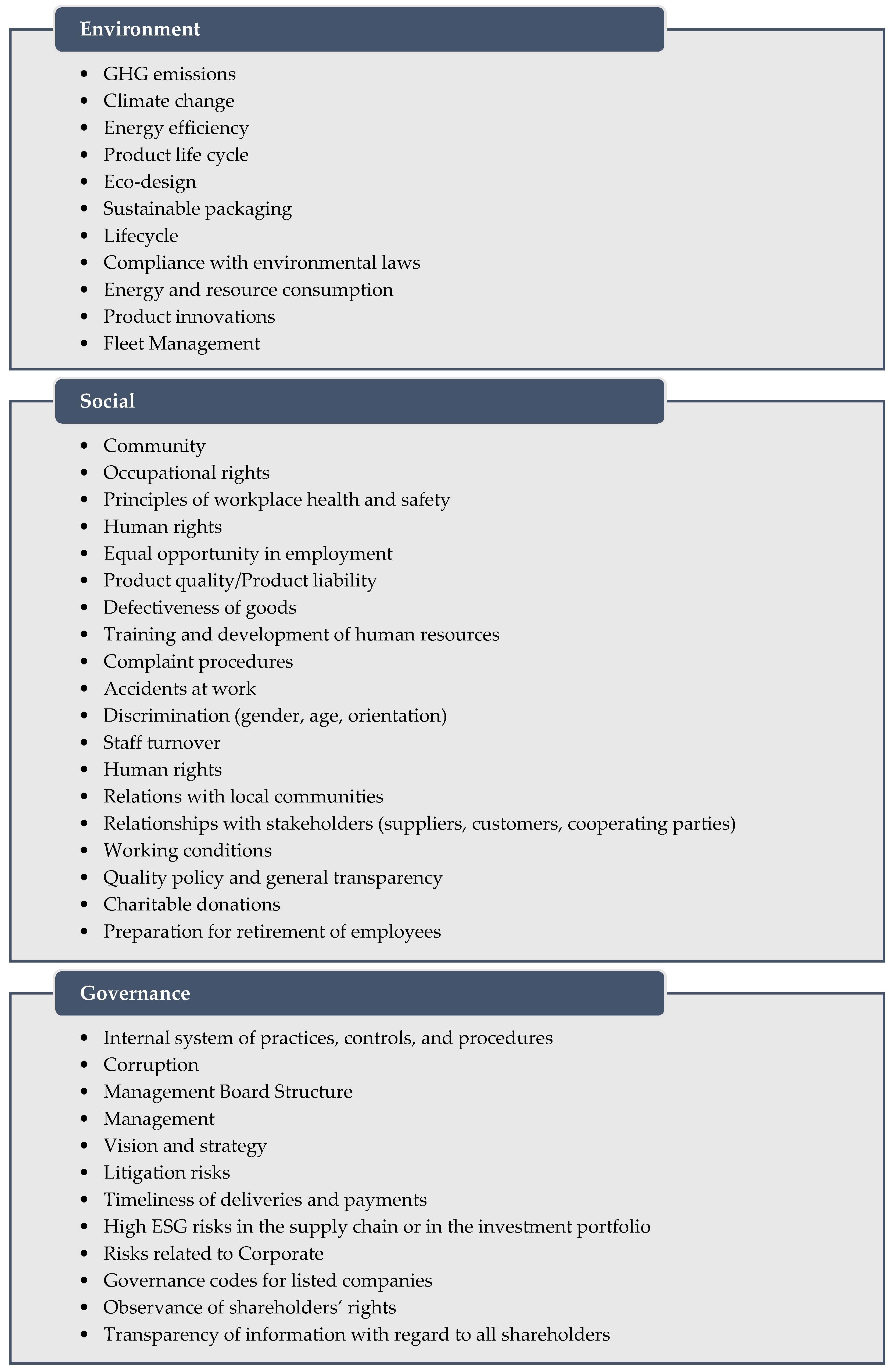

Figure 1).

A number of managers, analysts, scientists, researchers and policy makers believe that environmental issues, environmental responsibility and the implementation of ESG-related requirements are of considerable importance in the banking sector for several reasons. On the one hand, it is a way for banks to make up for the extensive use of funds that come from the public rather than from shareholders ([

19], p. 208). In addition, involvement in CSR activities can contribute to the improvement of the positive image of a bank [

20]—which is conducive to building the good and strong reputation of the bank [

20,

21]; growing trust in that entity among different stakeholder groups (employees, clients, suppliers, local environment—local communities and state administration, non-governmental organisations) [

10,

13,

22]; increased competitiveness [

21,

23]; greater innovation in management [

23] or more effective credit risk management [

19,

24]. Indeed, as far as environmental issues are concerned, in the context of credit management by banks, as Ahmed et al. [

18] duly noted, “any imprudent act on lending process might be perceived as banks’ failure to act responsibly. Any irresponsible lending might have negative impact on them in terms of criticisms, adverse publicity and imposition of penalty” ([

18], p. 71). Banking transparency provides stability and is a trust-building factor for the banking system as a whole ([

25], p. 13). Furthermore, as indicated by Nizam et al. [

10], “Banks are particularly interested in serving the social needs to build a strong local base for future sustainable business” ([

10], p. 38).

It should be stressed, however, that the principles of responsible lending or the inclusion of non-financial criteria—sustainable development factors—in actions taken are no longer of concern only to banks, they are also a matter of continued interest among investors, shareholders, corporate managers as well as financial corporations and non-banking institutions [

3,

23,

26,

27,

28]. Indeed, investment managers and financial analysts are aware of the need to include ESG/CSR criteria in the investment decision-making process and analyses [

3,

10,

29] and recognise the growing impact of social, environmental and governance (corporate governance) issues and/or social, environmental, ethical (SEE) criteria on the operation of their businesses [

27,

30]. Such innovative solutions in the aforementioned sector, as exemplified by the development of a concept of socially responsible investment (SRI), which involves the incorporation of ESG factors into investment decision-making ([

27], p. 112) ([

31], p. 196), can enable organisations to improve long-term profits/performance of financial portfolios [

23], provide an opportunity for sustainable, lasting growth in enterprise value [

17,

22] and allow investors to build and achieve competitive advantages in the future [

9,

10,

18,

24,

32].

Hence, CSR/ESG reporting needs to be a component of the organisation’s strategy-building and performance process [

33]. Some recommend that this approach should even be seen as an “investment in a core competence or asset” ([

24], p. 331).

Integrating ESG factors into the day-to-day operations of financial institutions has both a social and an economic aspect. In discussions on the social aspect, issues related to shaping society through appropriate measures and environmentally oriented business strategies should be considered before everything else. The activities of financial institutions indirectly influence the behaviours of citizens.

3. Literature Review

Europe has both geographically and politically set itself the goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 [

34]. It intends to achieve this goal by introducing specific legal frameworks, mobilising the financial sector—especially to change its approach to financing the transformation. This framework, now being designed and implemented, is expected to shift the focus of the energy transition to the financial sector. However, it is impossible to ignore the legal issues and their implications, which to a large extent permeate many financial decisions today and influence the practices and behaviours of banks [

35,

36,

37]. The emphasis on sustainable finance is not only driven by market pressures but also by regulations being adopted by the European Union as part of the European Green Deal [

34]. The EU has been the first economic community to establish ESG requirements, with the implementation of the EU Directive on Non-Financial and Diversity Information [

38]. More recently, it is also important to note that important organisations such as the European Banking Authority (EBA), European Association of Co-operatives Bank (EACB) and European Banking Federation (EBF) have initiated various activities and initiatives in the ESG area that have resulted in the finalisation of guidelines [

35]. In 2020, the European Commission adopted a so-called taxonomy for determining of which investments are sustainable or not, in addition to a package of solutions for the environmental impact disclosures that EU companies will have to make, and for the operation of financial institutions [

39,

40]. As the authors of the PwC study emphasised “Banks, among others, are the entities that—in line with the idea of the European Commission and politicians, and due to insufficient public funding in the EU—have a significant role to play in redirecting financing from high-carbon sectors towards low-carbon sectors or towards the energy transition. This will be done through changes in the investment and lending policies of financial institutions and will affect, among other things, lending to the real economy (with different impacts on climate through CO2 emissions, wastewater, water withdrawal, etc.). To the challenges of the financial sector must be added the implementation of ESG principles in the financial institutions themselves or in their subsidiaries, but also in their suppliers” ([

41], p. 2). As Cremona and Passador [

35] pointed out, “Such guidelines may indeed prove very useful for guiding boards in developing and implementing ESG policies within their respective corporate environments” ([

35], p. 10).

There are many different studies in the literature on the subject that analyse the relationship between corporate social performance (CSP), environmental responsibility management activities, especially including the incorporation and implementation of CSR or ESG criteria, and firm performance (FP): financial, operational, or its impact on financial effectiveness and shareholder value creation [

6,

10,

11,

18,

19,

26,

29,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47].

In their study, Ahmed et al. [

18] examined 30 selected private commercial banks in Bangladesh to assess whether or not, and to what extent, banks consider ESG criteria in the credit risk management process at all and to determine the motives for considering these criteria in the lending process. The findings of their study show that banks overwhelmingly take heed of basic ESG factors, in a qualitative manner, but they perform worse in terms of incorporating advanced ESG criteria. Regarding the motivation for implementing ESG-related requirements set by the EU legal framework, they found “banks taking initiative to consider ESG risk factors in lending analysis are rewarded through better financial performance” ([

18], p. 79).

Similar conclusions were reached in a paper by Shen et al. [

19] who, based on the results of their study, reported that “CSR banks overwhelmingly outperform non-CSR banks in terms of return on assets and return on equity” ([

19], p. 207).

In her study, Buallay [

43] analysed the relationship between ESG and operational, financial and market performance on a sample of 235 banks from 22 countries, listed on the stock exchanges of European Union countries between 2007 and 2016. The results demonstrated that “(…) the corporate governance disclosure [was] found to negatively affect the financial and operational performance (ROA and ROE)” ([

43], p. 16). In contrast, banks’ environmental disclosures have a positive influence on their financial and market performance.

Miralles-Quirós et al. [

6] evaluated the interdependence of banks’ social responsibility activities and shareholder value creation. They conducted their study on a sample of 166 banks from 31 countries (including seven banks from Poland) during the period 2010–2015. The researchers noted that “(…) there exists a negative and significant correlation of banks’ social performance with shareholder value creation” ([

6], p. 13). On the other hand, an inverse relationship holds for banks’ activities in terms of environmental and corporate governance aspects.

Broadstock et al. [

46], by studying a sample of 320 Japanese firms during the period 2008–2016, found that the firms’ commitment to CSR/ESG policies “(…) initially enhances their ability to pursue innovation activities and, then, eventually affects positively their value creation and financial/operational performance” ([

46], p. 99).

Moreover, Belasri et al. [

11] investigated 184 banks from 41 countries (including 5 banks from Poland) during the period 2009–2015 to assess the relationship between CSR activities and their financial impact. The findings suggest that “CSR only impacts positively bank efficiency in developed countries while it has no impact on efficiency for banks located in developing countries” ([

11], p. 20).

A study by Nirino et al. [

47], which concentrated on a sample of 356 listed companies in Europe, revealed that “ESG practices allow listed companies in Europe not only to be compliant with the law and regulations but also to increase financial performance” ([

47], p. 5).

Meanwhile, a study by Enala [

29], which focuses on financial markets in the United States: banks and financial services companies, listed on the New York Stock Exchange between 2002 and 2017, established that “(…) incorporating high ESG criteria leads to neither positive nor negative abnormal stock returns in the financial sector” ([

29], p. 77). The results supported the argument that “(…) it might just be that the true utility achieved from the implementation of ESG, and especially from Environmental dimensions, could just be too difficult to measure, as there is not any distinct way to estimate the financial benefits achieved from it” ([

29], p. 83).

A study by Henisz et al. [

16] showed that ESG criteria affect cash flows in five key aspects: “(1) facilitating top-line growth, (2) reducing costs, (3) minimizing regulatory and legal interventions, (4) increasing employee productivity, and (5) optimizing investment and capital expenditures” ([

16], p. 3).

In their study, Crespi and Migliavacca [

26] analysed 727 companies within the financial sector operating in 22 countries during the period 2006–2017 to determine which factors related to the firm, country and time influence corporate social performance. Their findings prove that “(…) big, solid and profitable financial firms are more likely to have high CSP, especially if they operate in a socially developed country with a civil law legal framework” ([

26], p. 17).

Additional contributions to this area of research can also be found in a paper by Nizam et al. [

10], where the authors evaluated the effect of social and environmental indicators on banks’ financial performance. They conducted their study on a sample of 713 banks from 75 countries, and covered the period of 2013–2015. They concluded that access to finance for projects with environmental impact has a very positive effect on banks’ financial performance, including return on equity (ROE). In addition, the authors noted that smaller banks (those with total assets below the threshold of USD 2.07 billion) will experience a more noticeable impact on their profitability compared to larger banks when it comes to access to finance measures.

Raut et al. [

48] reviewed sustainability implementations in the banking sector using the six largest Indian commercial banks as examples. The researchers suggest that, by and large, sustainability issues in banking services in India are not given enough attention for a country classified as an emerging economy. In addition, the findings show that “there is a misunderstanding of the role that corporate social responsibility plays with respect to environmental issues” ([

48], p. 577).

In summary, the literature review permits the conclusion that the aforementioned relationship can be broken down into at least two types of interdependences. Some studies have analysed the three ESG factors separately (environmental, social and governance performance) and linked them to FP. Other researchers, however, have tried to integrate these three aspects together and link them in a holistic approach to firm performance [

49]. It should be emphasised that the results obtained are not consistent with others or conclusive. Many empirical studies have found a positive relationship between the two. Nonetheless, other researchers have revealed that financial performance is negatively related or not significantly related to sustainability business practices. Nonetheless, the available literature does reveal that a number of empirical studies on the ESG-FP relationship recognise that the nature of the relationship between them is positive [

16,

18].

4. Materials and Methods

The primary objective of this paper was to identify the current condition of ongoing developments in EU legal regulations on ESG and sustainable finance. The following specific objectives were set: (1) assess the degree of preparedness of banks, banking associations and associations of cooperative banks operating in Poland for the implementation of ESG-related requirements set by the EU legal framework; (2) compare and summarise the existing practices/experiences in terms of non-financial reporting by the Polish banking sector; and (3) seek confirmation whether there are gaps in the EU legislation that prevent a harmonised approach to comprehensive and consistent integration of ESG factors by banks in their strategy and operations. Examination of the results of this study will help bridge research gaps in terms of answering the following research questions: what are the gaps in the EU legislation on ESG regulations enacted to date? What threats could arise from this? How can these gaps be misused by banks? How has the EU banking sector, using Poland as an example, started to prepare to consider ESG factors in investment decisions and daily operations? Are these regulations a suitable tool to sufficiently motivate banks to integrate environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) criteria into their lending decisions and long-term business strategies?

In order to achieve the objectives of this study, and to answer the research questions posed, an analysis of primary and secondary sources was performed in conjunction with a review of the (national and foreign) literature on the subject. In addition, the authors’ own professional experiences from years of work in the financial sector, including the banking sector, were used. Diverse research methodology of non-reactive research has been used in the design of this study: the doctrinal legal method and desk research.

The primary method used was the doctrinal legal method of analysing legal regulations on the EU level. This method served to show the factual state of affairs and ongoing developments in EU legislation on sustainable finance since 2018. To this end, primary sources were used. These include data from the EU Official Journal and the content of legal acts in doctrinal and legal terms, including EU publications, directives, regulations and guidelines of the European Commission and EBA were reviewed. The three major legal acts under analysis, related to ESG implementations in the financial sector, were: (1) Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards the disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups (text with EEA relevance) [

50]; (2) Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector [

39]; (3) Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 [

40]. Furthermore, the EBA’s guidelines and recommendations on sustainable finance were analysed, such as: Guidelines on Loan Origination and Monitoring [

4] as well as the EBA Report on Management and Supervision of ESG Risks for Credit Institutions and Investment Firms [

51].

At the same time, we performed a desk research analysis of secondary sources. The desk research analysis used content analysis, the analysis of existing statistical data, and the comparison of historical data ([

52], p. 19). Specifically, the analysis included: searching for information, identifying the dataset, completely assessing the dataset for relevance and quality, compiling, and processing [

52,

53]. The literature review included the following data sources: the data and summaries collected within the framework of public statistics and available in the form of Internet databases; publications, documents and reports available in the Internet collections of Polish and foreign scientific libraries and repositories. In addition, a source database was used in the form of electronic collections of publications available on the platform IBUK Libra, Lex, Legalis, Springer Link; Open Access resources were used, e.g., Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), OAIster, and licensed electronic sources, i.e., databases, e.g., EBSCO-host, Google Scholar, SCOPUS, Web of Science. A review of the existing literature on the subject was used in order to evaluate previous research, the current state of knowledge and to provide a theoretical background for the field of research undertaken by the authors. A review of the literature on the subject was carried out to determine how the concept of ESG is construed, and how it fits into the definition of CSR. It answered the question of whether, in light of the latest scientific research, ESG is an extension of corporate social responsibility or a separate development in response to the climate crisis. Moreover, using a systematic review of the existing bibliographical references published in the last six years (2015–2020), a comparison and summary of experiences with regard to the incorporation of CSR or ESG criteria by banks in Poland as well as an assessment of their level of involvement in measures for sustainable development were made. It should be pointed out that this study is a summary of research related to the ESG analysis of companies included in the RESPECT Index, because in recent years, the aforementioned index has been operating on the Polish Stock Exchange. The index selected companies (including banks) that acted and were managed in a sustainable and responsible way and at the same time emphasised their investment attractiveness. The establishment of the RESPECT Index (RI) in 2009 was the response to the global trend of the popularisation of socially responsible companies [

27]. It is “(…) the first index of socially responsible companies in Central and Eastern Europe, the project created by the Warsaw Stock Exchange (Polish: GPW), designed to identify companies that implement the CSR concept into their management strategy and to highlight their investment attractiveness in terms of the quality of published reports, the level of investor relationships or information governance ([

13], p. 86). Most banks in Poland that were compared by considering the CSR or ESG criteria in their activities were listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange [

17,

44,

54]. After ten years, the RESPECT Index was delisted and replaced by the new WIG-ESG stock index introduced by the Warsaw Stock Exchange on 3 September 2019 [

21,

55].

Additionally, the positions of the European Association of Co-operative Banks (EACB) and the European Banking Federation (EBF) and discussions of these institutions with EU authorities were reviewed in order to properly address the issue. To assess the status of preparations and the implementation of ESG obligations or recommendations by Polish banks, existing data found in the form of statistical and descriptive studies prepared by PwC were used. The data collected by PwC also gave some visibility to the problems reported by the banking sector in proper implementation of ESG rules.

Furthermore, the authors’ professional experience working in the financial sector was helpful in the proper development of this issue. The use of their own professional experience allowed the authors to confront the theoretical findings with actual market practice. In the field of legal sciences, this form of research, called law in action analysis, allows one to determine the actual functioning of the adopted legal solutions in a real environment. Therefore, especially with regard to legal acts, their usefulness in practice was analysed. This made it possible to identify the existing gaps and errors in legislation that hinder or prevent their practical application. In the part concerning legal acts, this study draws de lege lata and de lege ferenda conclusions, which are an inherent part of legal research.

The studies were parallel (data were simultaneously collected, compared and analysed together). The utilisation of the aforementioned data and the examination of the EU-level legal acts allowed one to obtain contextual information, answer the research questions posed in the paper and exposed the existing gaps and problems of the banking sector with respect to the application of existing or planned solutions.

5. Results

The Polish banking sector plays a significant role in investment finance for the enterprise sector. According to data presented by the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development, the share of the banking sector in investment finance varies depending on the size of the enterprise. Although internal financing accounts for the largest percentage of capital sources, regardless of the size of the enterprise, its share decreases in direct proportion to the size of the company. While the percentage share of equity allocated for development is high in the sector of large enterprises, in the small and medium-sized enterprises sector(SMEs), there is a noticeable increase in the level of funds derived from loans, amounting to approximately 9–16%, depending on the economic sector [

56]. One should not forget that according to the latest available data, mainly for 2018 and 2019, the share of the SME sector in Poland is huge, accounting for nearly 99.8% of all actors in the national economy, which is responsible for 50% of the GDP ([

56], p. 6). Thus, the role of the banking sector in the financing of enterprises and innovative activities in the Polish enterprise sector is significant.

The foregoing leads to the realisation that banks indirectly have a large impact on innovative solutions chosen by businesses through the dedication of their finance offers to particular sectors of the economy. The Polish banking sector has a dual structure—divided into commercial banks and a large network of cooperative banks—which operates independently or within associations. As of the end of July 2021, there were 30 commercial banks operating in Poland in the form of joint-stock companies and 521 cooperative banks [

57]. This division has its historical roots in the Polish cooperative movement traditions dating back to the 19th century. Commercial banks primarily target the residents of cities and towns as well as businesses based in large cities and small localities. Cooperative banks, on the other hand, provide a counterbalance and an alternative to commercial banking, often remaining close to the people and the local community. Their area of operations mainly covers rural communes and small towns. This is related to the idea of cooperatives, whose overriding objective superior to the commercial objective is to support the development of the local community ([

58], p. 71). The offer of cooperative banks has been largely addressed to local communities—in particular to craft-based and agricultural communities. As A. Surma-Syta duly pointed out, “The importance of these banks is still great particularly in the sphere of their activities for the benefit of the local communities” ([

59], p. 67).

Banks and other financial institutions have become drivers of change in consumer and business behaviour. In 2018, the European Commission was already aware that banks are an important link in the chain that could lead not only to a physical zero-emission-oriented transformation but also to a worldview transformation. The significance of banks in this regard has been embedded in the EU’s pro-climate policy. In 2018, the European Commission announced an action plan for sustainable growth. The plan sets out three main objectives. First of all, by means of suitable legal tools, banks should reorient capital flows towards sustainable investment. Furthermore, they should manage financial risks resulting from climate change, which in the long term, could lead to environmental degradation, resulting in social stratification and problems [

1]. These stratification and social issues will also affect banks. As the European Commission rightly pointed out, “(...) Banks will also be exposed to greater losses due to the lower profitability of companies most exposed to climate change or highly dependent on dwindling natural resources” ([

1], p. 3), [

60]. Thus, the European Commission in 2018 recognised that threats to the financial sector in the form of inadequate risk management policies are real and that ESG needs to be included in a separate risk category. By doing so, the EU has highlighted a sectoral gap that could lead to irreversible consequences in the financial sector. As a result of the European Commission’s communication, legislative work was initiated with the aim of introducing suitable legal tools into the market and a number of guidelines were issued by the European Banking Authority. These tools, taking the form of regulations and directives of the European Parliament, intend to unify the pro-environmental approach across the whole EU financial sector. One of the major legislative achievements of the last 3 years is Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment [

40], amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 [

39], also known as the EU taxonomy. The regulation was the first to become a tool designed to facilitate investment decision-making for companies and investors, oriented towards environmentally sustainable objectives. The system set out in the taxonomy will have to be primarily used by financial market participants, but only those listed in the definition provided in Article 2 (1) of Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 (SFDR—Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation), including manufacturers of a pension product in respect of which the member state has chosen to apply that Regulation in accordance with Article 16 [

39], and by financial and non-financial corporations subject to non-financial reporting, i.e., public benefit corporations with more than 500 employees [

50].

In view of the fact that the banking sector in Poland is a dual system subdivided into commercial and cooperative banks, the solutions adopted at the EU level with regard to the applicability of the taxonomy exempt certain financial market participants from the obligation to apply it. While commercial banks by definition fit into the framework of taxonomy application, cooperative banking only does so to a limited extent. According to the definition in Article 2 of Regulation 2019/2088 [

39], a financial market participant is defined as, inter alia, an insurance undertaking which makes available an insurance-based investment product, an investment firm which provides portfolio management, an institution for occupational retirement provision, a credit institution which provides portfolio management. Therefore, as far as the definition is concerned, Polish cooperative banking is not covered by the obligations set out in the text of Regulations 2019/2088 [

39] and 2020/852 [

40]. A majority of the 521 cooperative banks operating in Poland do not have a statutory object that would qualify them as a financial market participant under Regulations 2019/2088 [

39] and 2020/852 [

40]. This fact reveals certain incongruity and oversight on the part of the European Parliament which has led to exempting a significant proportion of financial institutions in Poland and Europe from reporting obligations and applying the taxonomy. It would seem reasonable to argue that differences specific to financial sectors of individual EU countries were not taken into account at the drafting stage. At the same time, the European Association of Co-operative Banks stated that even if the taxonomy or the reporting obligations apply to some part of the cooperative banking sector, their full application will still entail multiple problems [

61]. As mentioned earlier, the clients of cooperative banks are essentially enterprises in small-scale trade, craft and local agriculture. These businesses have also been exempt from the application of pro-environmental EU regulations on ESG disclosures. Financial reporting or the use of the taxonomy to assess whether an investment in which a local bank intends to participate is environmentally sustainable is based on data obtained from the interested party. If that party is exempt from the reporting obligation and does not collect data or carry out environmental assessments of its activities, the local bank will not be able to do so either. The EACB rightly pointed out in its 2020 report that “One big obstacle to the full implementation of the current action plan and the next strategy is the lack in ESG data” ([

62], p. 27).

This gap additionally creates difficulties in the implementation of EBA guidelines titled Guidelines on loan origination and monitoring [

63]. This paper, consulted with financial sector actors, provides a clear recommendation on how ESG risks can and should be managed and what impact this will have on prudential requirements [

64]. According to Section 4.3.5 of the guidelines [

4] “Institutions should incorporate ESG factors and associated risks in their credit risk appetite and risk management policies, credit risk policies and procedures, adopting a holistic approach” ([

4], p. 26). At the same time, “Institutions should position their environmentally sustainable lending policies and procedures within the context of their overarching objectives, strategy and policy related to sustainable finance. In particular, institutions should set up qualitative and, when relevant, quantitative targets to support the development and the integrity of their environmentally sustainable lending activity, and to assess the extent to which this development is in line with or is contributing to their overall climate-related and environmentally sustainable objectives” ([

4], p. 27). Due to the gap in the application of the taxonomy and the restriction of only applying non-financial reporting to large corporations, compliance with the guidelines poses quite a challenge for the banking sector, particularly the cooperative banking sector, when it comes to the proper integration of ESG factors, lending activities and the proper assessment of enterprises in terms of sustainable operations. As the European Banking Federation pointed out in its statement of 6 September 2021: “We expect a balanced, ambitious and robust framework that clearly defines what can be considered socially sustainable in doing business, also from the point of view of corporate lenders who want to have a positive social impact. In particular, we expect metrics to apply the ‘do no significant harm’ and ‘substantial contribution’ criteria, as well as concrete examples of thresholds for ‘do no significant harm’ and ‘substantial contribution’ criteria with worker, consumer and community objectives, by activity and at entity level (meaning both at horizontal and vertical level). It is also desirable that the social taxonomy is consistent with current market standards. A social taxonomy should also enable aligned transactions to be included in European re-financing programs, as it is the case for ‘green taxonomy aligned’ financial products” ([

65], p. 2). It is also important to note that ESG risks should not only be incorporated in the lending area, but also in many other aspects, including flow analysis, pricing policy, collateral valuation, internal limits and risk appetite [

66].

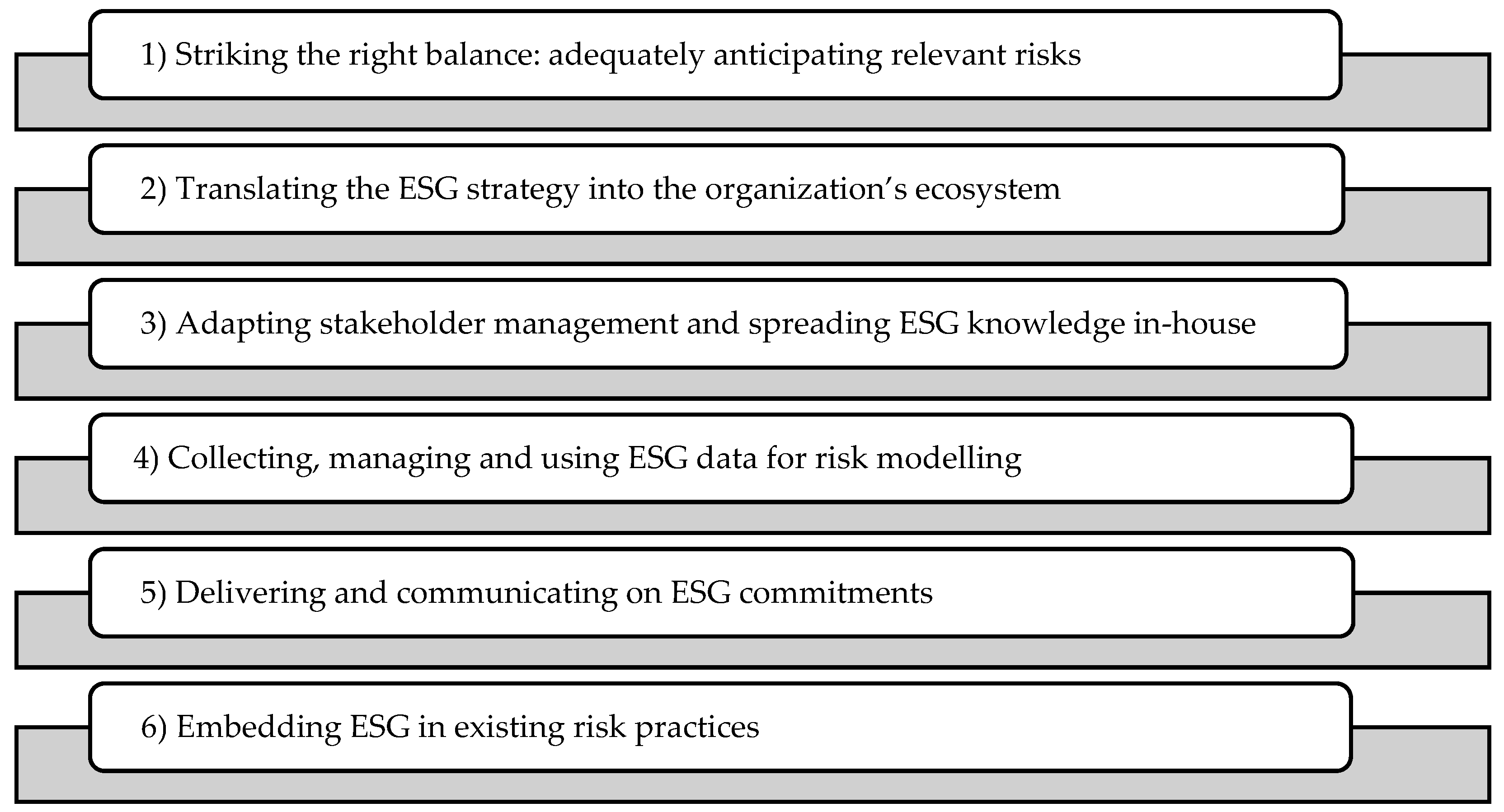

The implementation of ESG solutions in the lending process as well as in considering ESG factors in bank risks meets many technical and legal obstacles. The auditing firm PwC has identified six main challenges across the European banking sector that banks face in implementing ESG solutions into their credit analyses and risk management strategies [

67]. While the EU taxonomy or EU regulations provide a general interpretation framework, the greatest problem for banks remains their implementation in practice. The top six challenges for the banking sector in ESG implementation as pointed out by PwC in its report, are displayed in

Figure 2 [

67].

The above analysis is in line with the general view of EBF. The EBF also conducted a survey among European banks that revealed similar problems in the implementation of ESG solutions. The main factors impeding the implementation of ESG factors in practice were identified as [

68] (1) lack of international convergence; (2) lack of methodologies; (3) lack of data and lack of resources.

The results of studies conducted for the entire EU banking sector are consistent with the results for the Polish sector. In fact, according to a survey conducted by PwC Poland, the following major challenges were identified in relation to the requirements of implementing ESG factors into the risk framework [

41]: (1) the lack or limited availability of counterparty ESG data; (2) low quality and awareness of disclosures, and counterparty awareness of ESG factors; (3) lack of final, transparent regulations. By the same token, “More than half of the institutions (57%) also perceive lack of adaptation in terms of IT systems or internal processes in banks as significant challenges in relation to the requirements to implement ESG factors into the risk framework. Almost 40% recognise the risk of implementing ESG regulations in an overly mechanical fashion through European Commission regulations rather than EU directives, which may entail a lack of due regard to negative local effects of ESG implementations on bank clients. This may happen as a consequence of using regulations to force an ESG transformation that is too fast, too radical or does not take into account e.g., social costs, or underestimating the impact of ESG on competitiveness of the Polish economy (firms, private clients)” ([

41], p. 18). This state of affairs can be regarded as the aftermath of regulatory solutions adopted at the EU level, which exempted a considerable part of enterprises operating on the European market from the use of the disclosures and the taxonomy. As indicated above, the EU taxonomy or SFDR mainly applies to large economic operators, which should be engaged in non-financial reporting. The European legislation has largely exempted the SME sector, which constitutes the backbone of the economies of European countries such as Poland, from the application of the aforesaid regulations. This has a negative impact on the implementation of ESG rules, especially with regard to credit exposure management or risk management.

In mid-2021, EBA published its Report on Management and Supervision of ESG Risks for Credit Institutions and Investment Firms [

69]. The report was designed to provide guidelines for the banking sector as it “(...) provides a comprehensive proposal on how ESG factors and ESG risks should be included in the regulatory and supervisory framework for credit institutions and investment firms” [

69]. The report states that “The supervisory review should proportionately incorporate ESG risk-specific considerations into the assessment of the institution’s internal governance and wide controls, monitoring how ESG factors and risks will be incorporated into the overall internal governance framework, the functioning of the management body, the corporate and risk culture, remuneration policies and practices, risk management framework and information systems and internal control framework” ([

51], pp. 142–143). The EBA report offers a set of guidelines for the incorporation of ESG factors in banking but does not address the problematic lack of data for the proper application of the taxonomy. As the EBA rightly noted, “With regard to the comments received on the EU taxonomy, it should be noted that the development of the EU taxonomy has a number of implications for the banking sector. The taxonomy by and of itself cannot cover all needs and, as outlined in this report, institutions should consider a range of actions to appropriately deal with the impacts of ESG factors” ([

51], p. 165).

The aforementioned legislative gaps lead to an inability to make the right decisions in the implementation of ESG factors in the banking sector, and some solutions are overlooked. Using Poland as an example, the non-financial reporting system that was incorporated into law in 2014 under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) (2014/95) [

50] was implemented by a minority of banks.

As Aluchna [

70] rightly pointed out, there are many challenges to reporting ESG information. The first will be the use of comparable standards that allow one to determine the progress in this area over time. Another challenge will be to improve the quality of these reports, as some banks choose information that is more convenient to report or that is easier to meet, i.e., information in which they can report more progress. R. Hummel [

70], the leader of the ESG reporting group of the Audit Department in EY Poland, also emphasised that financial institutions need to work hard to prepare for this reporting in a qualitative way. First of all, they need to set a strategy and quantify sustainability goals in the area of the financial services sector. Then, these ensure that they have systems in place to collect the data, and will need to build a process that also includes internal controls, which are elements that verify that the information being reported is complete and true. The Association Banks in Poland, that is the SGB Bank S.A. [

71] and BPS Bank S.A. [

72], do not have ESG factors in their long-term strategies, but only mention the necessity to take them into account, among others, in credit risk. The actions taken by them are only an attempt to adapt to the increasingly new regulations and guidelines of European authorities. This is evidenced by the fact that the aforementioned banks do not publish information on their websites about strategies related to sustainable financing and development, in contrast to the leading commercial banks in Poland, such as [

73]: Bank Ochrony Środowiska S.A. [

74], Credit Agricole Bank Polska [

75], BNP Paribas Bank Polska [

76], Santander Bank Polska [

77], Bank Handlowy w Warszawie S.A. [

78] and Bank Millennium S.A. [

79].

In the context of the new regulations of the European Parliament and the Council of the EU related to the environmental aspect, in conjunction with the promotion of pro-environmental behaviour and actions, new problems also arise [

80]. These consist in the fact that the obligation to use ESG data leads to the creation of a market for ESG information. The phenomenon of the monetisation of ESG data, particularly visible in Western Europe but also in Poland, is taking place [

81], which means that these data must be paid for. These reports will generate costs for banks. While the large commercial banks will be able to absorb this new financial burden, the cooperative banking sector will not. Therefore, the banking industry is calling for equal access to these data in the form of a government-sponsored or EU-wide single catalogue of such data. Hence, there is a new idea/project to build one centralised digital ESG database in the EU to counteract unequal conditions of access to ESG data.

In practice, the application of EU legislation, which in principle uses vague and ambiguous concepts, also raises interpretation problems and therefore does not lead to the uniformity of solutions across the EU. Despite the issuance of legal acts and guidelines of supervisory authorities, there remains a lack of practical guidance on how the banking sector should implement the assumptions of EU legal acts. The authors pointed out from their own experience that banks do not present a uniform approach to the issue of ESG and the differences are significant. This is particularly evident in cooperative banking, which is fragmented. Although most of the cooperative banks in Poland are part of and supervised by so-called Association Banks [

71,

72] (SGB Bank S.A. and BPS Bank S.A.), which by law should support associated banks in the transposition of legislation, this mechanism does not function legally. There is no consensual interpretation approach at the level of bank associations, which is not helped by the lack of guidance from The Polish Financial Supervision Authority. There is a large disproportion in the application of EU regulations, and the lack of knowledge or uncertainty about their interpretation is not conducive to their proper implementation in internal acts. The implementation of ESG solutions in banking activities, especially in the co-operative banking sector in Poland, is also not supported by the lack of specialised staff. The ESG market is a young market, because so far it has only concerned those entities that were obliged under the binding regulations to provide non-financial reports. This results in staff shortages that are impossible to overcome during a short period of time. The multitude of EU regulations and their level of complexity and ambiguity of interpretation require the market to create a new class of specialists, who must not only have legal knowledge, but also the knowledge of management and environment. Qualifying existing staff and creating new ones is a big challenge for the market. What becomes apparent here is the lack of opportunities for specialised education in this direction. At Polish universities, the lack of faculties, which in a comprehensive way would educate specialists in the field of ESG is highlighted. We are not talking only about comprehensive fields of study, but also about the lack of postgraduate studies or specialised subjects in existing studies. In this regard, we can see a large disproportion between Poland and western European countries. Many leading European universities (e.g., Oxford)have offered courses, training and study programs on sustainable management and sustainable development for many years. In Poland, the market for this type of teaching services is still nascent. Therefore, there is a large shortage of staff, which affects the proper implementation of ESG in management. According to the authors, the market for teaching services has not kept up with the legislation and the EU legislation itself has not created the need for such a market in Poland. The reason for this phenomenon may be the fact that the political environment in Poland is not conducive to ecological transformation. Poland’s energy policy is based on fossil fuels, and the transition away from them is not planned for yet another 20–30 years. This leads to the conclusion that companies, and therefore the financial sector that finances them, do not see the need for the rapid transformation of their services in the direction of ESG. Since the market trend towards a more ecological approach is developing slowly, the banking sector in Poland, particularly the cooperative banking sector, does not see any tangible benefits to financing transformation in the near future. With reference to cooperative banking in Poland, we should not forget that it is mainly a source of financing for agricultural activities. From the authors’ experience of working for the cooperative banking sector in Poland, it appears that the agricultural sector is sceptical about the ecological changes imposed by EU legislation. Therefore, the cooperative banking sector in Poland faces the challenge of not only implementing ESG factors in its operations, but also educating agricultural customers that changes in attitude towards the environment and the need to protect it is important for their continued existence.

6. Discussion of Sustainability Performance: Evidence from the Polish Banking Sector

The literature offers a wide selection of papers and studies that focus on assessing the position of the Polish financial sector in terms of its involvement in measures for sustainable development. We presented some of the existing non-financial information reporting practices used by the banking sector in Poland below.

Korzeb and Samaniego-Medina [

25] analysed the involvement of 14 commercial banks operating in Poland (including seven domestic banks with predominantly Polish capital and seven with predominantly foreign capital) in sustainable development during the period 2015–2017. The authors used the TOPSIS method for this purpose. Their study revealed that “(…) most commercial banks do not disclose sustainability reporting, nor do they publish it on their websites” ([

25], p. 13). Moreover, some information was made available by banks on their websites with a significant delay. In addition, the study showed that the largest banks in Poland in terms of assets and net profit, listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, are more likely to engage in actions for sustainable development.

Wójcik-Jurkiewicz [

55] evaluated the impact of non-financial reporting practices followed by the banking sector in Poland. She conducted her research on eight commercial banks, included in the WIG-ESG index (the WIG-ESG index is a new index launched in Poland by the Warsaw Stock Exchange, replacing the previous RESPECT index (delisted on 1 January 2020); WIG-ESG has been published since 3 September 2019 and its purpose is investment-related) [

21,

55], listed on the Polish Stock Exchange in Warsaw, which are subject to non-financial reporting obligations on the Polish market in this respect. In her analysis, she used the contents of eight non-financial reports of the banks for the reporting year 2019. The study showed that 5 out of 8 banks declared to have accomplished at least one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and only 3 banks could be described as “socially responsible”, as they met the social parameter proposed by the author, which was the banks’ membership in the now defunct RESPECT index for a period of five consecutive years ([

55], p. 222). The results of the study also indicate that “(…) banks make different choices as to the type of social issues presented, their place and manner of publication, and even the measurement procedures used” ([

55], p. 224).

A similar study was conducted by Świrk [

21] in 2020, using information from the official websites of WIG-ESG indexed companies. It showed that of the 10 commercial banks included in the WIG-ESG index and listed on the Polish Stock Exchange, only 2 have a declared environmental responsibility in the context of future generations.

A study conducted by Czerwińska and Kaźmierkiewicz [

82] found that the reporting of non-financial data is at a low level on the Polish market, and confirmed that there is a large information gap regarding ESG reporting by listed companies in Poland.

One study conducted by Matuszak and Różańska [

54] using a dataset from 2008 to 2015 for 18 commercial banks in Poland established the relationship between CSR and FP. The study found a positive relationship between banks’ CSR disclosures and their profitability as measured by the ratios: return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE).

In her paper, Marena [

83] reviewed the position of the Polish financial sector in the global and regional financial system, suggesting that “(…) Poland’s financial sector is still of a mixed type, demonstrating the features of both developed and emerging markets” ([

83], p. 14).

The study conducted by Zioło et al. [

84] in 2019 among 60 Polish enterprises revealed that, in general, “(…) enterprises that declare a sustainable business model are more likely to implement sustainability-related actions than those enterprises that have not implemented such models” ([

84], p. 1504). Furthermore, the authors of this paper found that banks have a positive impact on decisions made only by those enterprises that have sustainable business models. This positive impact pertains to aspects such as: “(…) financial management, risk management, human resources management, and pro-environmental and pro-social activities” ([

5], p. 1515).

Another study by Zioło et al. [

7] concluded that “Poland is a country with one of the strongest ESG risks, and a poorly developed social awareness of the environmental factor” ([

7], p. 26).

Of note is the fact that, in the studies under review concerning the assessment of non-financial reporting practices employed by the banking sector in Poland, the researchers have followed various criteria, taken into account different datasets and intervals, or used varying methods and techniques to conduct their research. However, despite the differences in data collection and measurement methodologies, the review of empirical evidence has revealed that a majority of commercial banks in Poland do not make disclosures and do not publish non-financial information on their websites. In addition, the banks that do choose to publish it use different methodologies, which contradicts the standardised approach and is a major setback for the financial sector. Therefore, there is a large information gap regarding ESG reporting by commercial banks in Poland.

As far as cooperative banking is concerned, it was obviously excluded from non-financial reporting under Directive 2014/95 [

50]. The reporting essentially applies to entities in the financial sector but only those that meet the criteria and requirements set out in the Directive. This situation has also not been changed by the entry into force of the SFDR and the EU taxonomy. The interrelation between these regulations is still preserved and the exemptions continue to apply. Thus, the EU has divided the financial sector into entities that must comply with the regulatory requirements and those that might only do so voluntarily. This raises the question of whether this is the correct approach, given the fact that both small enterprises and small local banks play a significant role in the lending process and are exposed to ESG risks just as much as commercial banks. Directing the EU’s pro-environmental measures towards large entities only is unwarranted in the authors’ opinion. Considering the fact that the SME sector comprises a substantial proportion of the enterprise sector, the exemption from application of certain solutions poses a threat to the implementation of proposals and goals set out in the European Green Deal in connection with sustainable finance.

7. Conclusions

The literature on the subject, as well as EU representatives, agree that banks are a key link in attaining the objectives of sustainable development and finance. However, this requires the reorganisation and adaptation of the financial market to its specific circumstances. EU regulations are still in their drafting stage. Nevertheless, the results of the analysis performed herein suggest that the European Parliament regulations issued to date require a number of amendments. Current EU legislation on ESG and sustainable finance [

39,

40,

50] primarily targets large commercial banks and does not cover a substantial part of enterprises, especially in the sector of SMEs and local banks. One of the key conclusions, with respect to achieving the objectives of the study, is the confirmation that there still are gaps in the EU legislation that prevent a harmonised approach to the comprehensive and consistent integration of ESG factors by banks in their strategy and operations. Banker associations have voiced extensive criticism of the regulations, which are viewed by banks as inadequate, unclear and inconsistent [

62].

To bring about a complete transformation in the financial sector, local banks and SMEs must also be involved. The limitation of application of the three major legal acts reforming the financial sector with respect to the implementation of ESG solutions is a gap that may, in the long run, compromise EU’s zero-emission and sustainable finance efforts. By way of example, we should point to cooperative banks, which are an important link in financing SMEs, including small-scale farmers and craftspeople. Without the involvement of local banks and the SME sector in the fulfilment of tasks mandated by the legislation in question, there will be no transformation, neither energy-wise nor worldview-wise, in these sectors. It should also be noted that some of the solutions designed for commercial or cooperative banks (insofar as they are covered by the provisions of the legal acts) are not comprehensive, and there are no tools in place for their proper application.

As a consequence, looking at the example of Poland, as revealed by the review of nine pieces of empirical evidence of existing practices in this area [

5,

7,

21,

25,

54,

55,

82,

83], most commercial banks do not make disclosures and do not publish non-financial information on their websites. In addition, the banks that do choose to publish such data use different methodologies, which contradicts the standardised approach and is a major setback for the financial sector. These actions do not raise the public awareness of the environmental factor, where Poland, as empirical evidence suggests, incurs one of the strongest ESG-related risks in the EU [

7]. To some extent, the gaps regarding the application of the regulations were closed by the EBA [

4,

51]; however, its actions seem to be insufficient. Although there has been a dialogue with the banking sector and partial agreements have been reached on the harmonisation of the approach to ESG implementation, it is the authors’ opinion that both the EU legislation and the EBA guidelines as they stand today are still in their early stages of development.

Thus, it is recommended that the SME sector and local banking be included in the transformation process by imposing certain obligations under EU law. Without the proper inclusion of entities that play a significant part in small, local communities, the transformation cannot be comprehensive. The lack of inclusion of the SME sector generates the risk of legislative solutions being illusory, as they have only covered large enterprises. We suggested a gradual inclusion of all economic operators on the European market in reporting obligations and the obligation to assess climate-related risks.

At the same time, it should be noted that despite the creation of a number of legislative tools, there is no appropriate educational base on the Polish market that would educate in the field of ecological transformation. These deficiencies might be the result of the climate policy of the Polish state, whose energy policy is based on fossil fuels. A number of educational activities should be undertaken in this regard, in accordance with the current European legislation. The goal of changing the worldview not only in the banking sector but above all among its customers is impossible to achieve without properly educated banking staff and extensive promotional campaigns. The climate awareness in the area of SMEs and the agricultural sector in Poland is low, and there is a certain scepticism in the transformation plan presented by the EU. In this aspect, it becomes necessary to properly prepare bank employees to act not only as financial advisors but also as ambassadors of the ESG idea among their customers. It is only this approach that guarantees that the law will not just be a legislated law, but primarily a living law that reflects the actual EU climate policy and involves citizens in its implementation.