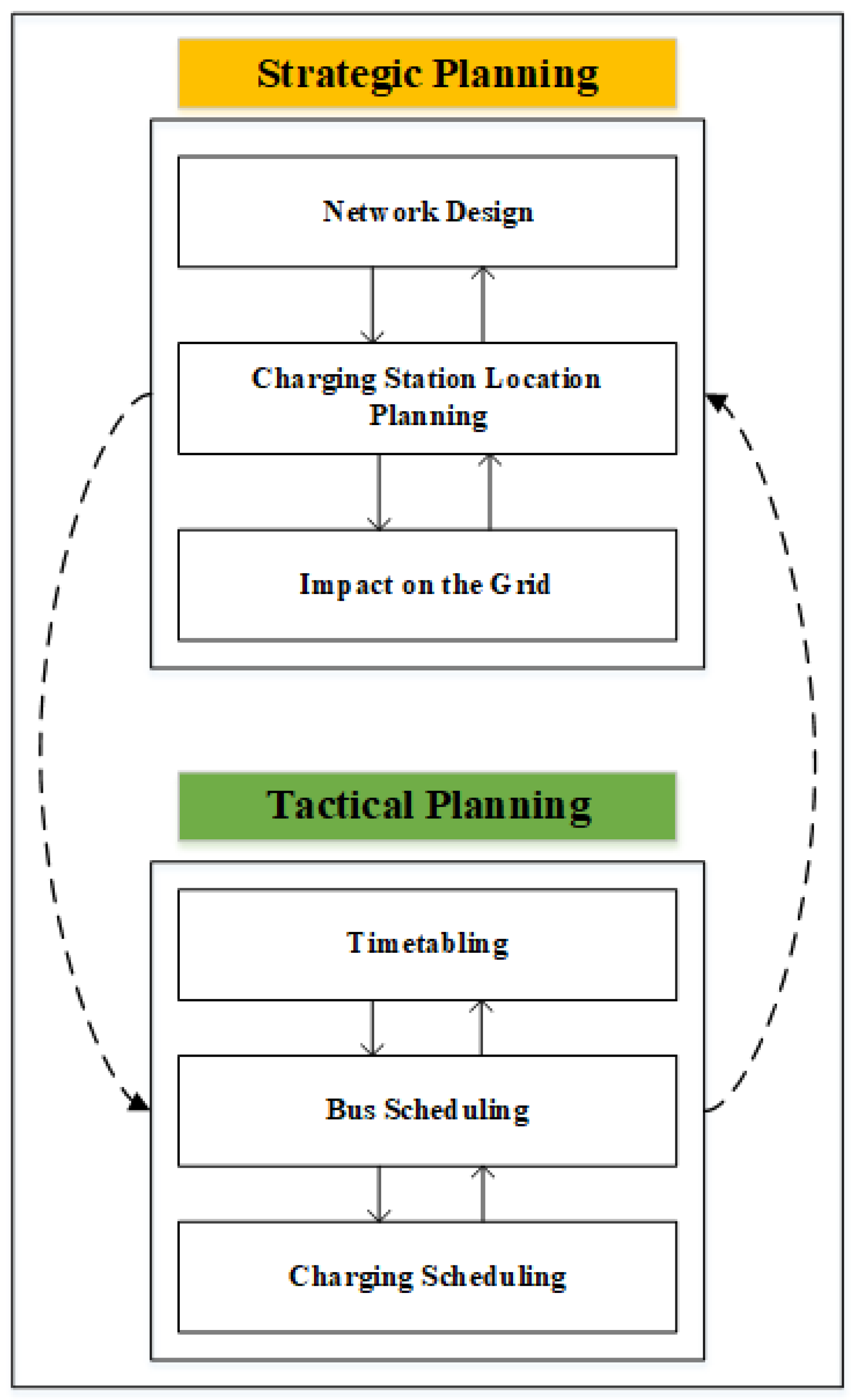

In this section, first, brief background regarding different types of charging station location planning approaches are described. Then, a detailed review of the literature on fast charging infrastructure locations and recharging planning is given. In the next part, a concise overview of bus scheduling and timetabling is presented, followed by a comprehensive investigation of studies focusing on the integration of bus scheduling and timetabling.

3.2. Bus Timetabling

A “good” timetable has different meanings from passengers’ points of view. One may recognize a good timetable by its regularity, whereas another will prefer a timetable with the exact headway or frequency that he wants; or a good-quality timetable may be represented by the minimum difference between the actual and desired frequency. Thus, determining a timetable would be challenging due to several objectives that should be satisfied. Minimizing the waiting times of passengers and maximizing the bus-line-departures synchronization are the main objectives of timetabling. Improving safety, quality of service, and comfort are the other objectives of the bus timetabling problem.

Researchers addressed the timetabling problem from various angles. Multi-objective models, which simultaneously reduce the passengers’ waiting times and increase bus utilization [

89,

90,

91], maximizing bus frequencies to satisfy the passengers’ travel demands [

92], and maximizing uniform loading on buses through even-load headways [

93]. According to [

94], depot charging does not affect electric bus timetables. Thus, the timetabling approaches and their methods for conventional buses could be implemented on EBs without any modifications. However, fast-charging affects the development of bus timetabling. The time taken for charging, which is about 5 to 10 min, should be considered when generating the timetable. Although fast-charging technology affects the timetabling problem (the recharging time should be added as an input to the problem), there is no study in the literature modeling the problem of electric bus timetabling specifically. Note that overnight and continuous wireless charging have no impact on generating timetables. According to [

94], the methods to deal with the timetabling problem for conventional buses could also be implemented on EBs.

Ceder et al. [

95] presented a mixed-integer model to create timetables with the maximum synchronization of bus arrivals at transfer stops. Since the suggested mixed-integer programming model belongs to an NP-hard set of problems, a heuristic approach was presented to solve the large-scale problems. Liu et al. [

96] solved this problem using the Nesting Tabu Search algorithm. Ibarra-Rojas and Rios-Solis [

97] solved this problem while avoiding bus bunching of bus lines. Minimizing the passengers’ waiting times has been addressed in [

98] through optimizing the synchronization of bus arrivals at the connection nodes in the network. The authors solved the problem by formulating a MILP model. Parbo et al. [

99] investigated the maximal synchronization problem to minimize the passengers’ waiting times by focusing on the social benefits of the created timetable.

Ceder et al. [

89] developed a multi-objective model to reduce the expected waiting times of randomly arriving passengers while increasing bus utilization from the operator’s perspective. Zhang et al. [

91], in 2020, proposed a decomposition heuristic algorithm to solve the multiple-vehicle-types scheduling problem and introduced a bi-objective optimization model for a feeder bus line to reduce operating costs and passenger waiting times with consideration of three different types of buses.

Shang et al. [

92] proposed a timetabling problem for maximizing bus frequency and headway based on customer satisfaction. The timetabling is optimized by striking a balance between customer satisfaction and bus transit performance, taking the load factor into account. Ceder and Philibert [

93] developed an approach for creating even-load transit timetables to achieve a uniform maximum load on vehicles and seamless transfers. Due to the low load discrepancy, such even-load timetables would improve vehicle utilization and minimize empty seat-minutes. However, they would prolong the waiting periods for passengers arriving at random stops. Gkiotsalitis and Alesiani [

100] presented a robust timetable using a bus movement mathematical model which incorporates travel times and passenger demand uncertainty to reduce the potential loss in worst-case scenarios by minimizing the deviation between actual departure times of buses and the desired ones.

3.4. Integration of Bus Scheduling and Timetabling

This portion of the literature discusses the integration of timetabling and vehicle scheduling problems. Häll et al. [

94] studied the EBs timetabling and vehicle scheduling changes, seeking to optimize various charging methods, including continuous, overnight, and quick charging. The authors investigated the effects of introducing EBs on public transportation’s operational planning (transit network, timetabling, and scheduling). Integration of electric bus timetabling and vehicle scheduling is required to meet passengers’ demands, enhance social benefits, and reduce operator costs [

90]. Hence, finding the optimal timetable and vehicle schedule for electric buses is a key factor in reaching a more sustainable transit system. Most previous studies considered bus scheduling and bus timetabling individually and separately. Ceder et al. [

128] and Chakroborty et al. [

129] were the first researchers who studied the integration of TT and VS. Ceder et al. addressed an approach for combining timetables and vehicle scheduling from both the customer and the operator’s perspective to reduce the fleet size. Their approach was based on a four-step sequential method with a feedback loop. Chakroborty et al. addressed the problem without the interlining option and minimized the fleet size while reducing passengers’ transfer and waiting times, based on a genetic algorithm approach. Most of the studies in the literature mainly discuss the minimization of passengers’ waiting and travel time for timetabling and minimization of bus operator costs (purchase costs of new buses, deadhead trip costs, scheduling, and recharging costs).

The combination of bus timetabling and scheduling is a bi-objective problem. On the one hand, it should optimize the passengers’ satisfaction by minimizing waiting time, travel time, seat availability, and so on; on the other hand, it should consider operational costs from the bus companies’ point of view. These two objectives are in conflict, and to solve and handle such issues, several strategies could be adopted: shifting, weighting, Pareto front, bi-level programming, and reordering.

In shifting, VS could be solved with minor changes in the timetable, i.e., small shifts in arrival and departure times to reduce the operational costs of scheduling. In this approach, a selected objective function would be optimized regardless of another objective function on the condition that the second objective will not exceed/be less than a given threshold value. Kliewer et al. [

101] were the first scholars who introduced shifting strategy for vehicle scheduling problem, which is called the vehicle scheduling problem with time windows (VSP-TW). They used a time-space network to find out the feasible combinations of trips and solved the problem using heuristic and column generation methods. Fleurent et al. [

130] and Van den Heuvel et al. [

131] extended the model presented by Kliewer et al. [

101], proposed a hierarchical approach to solve the vehicle scheduling problem, and used mathematical programming models to find the best number of vehicles and optimize the type of vehicles based on a simulated annealing (SA) approach. A combination of shifting and weighting strategies based on a metaheuristic approach was developed by Fonseca et al. [

132]. They aimed to minimize the total operational costs while minimizing the passengers’ transfer times.

The weighting strategy is one of the most straightforward strategies to dealing with such a problem, but the issue is determining the weights’ best values to describe the preferences of passengers and public transportation service providers. Petersen et al. [

133] introduced a new problem to simultaneously address passengers’ waiting time and total resource costs for an integrated TT and VS problem. They solved the model based on the large neighborhood search (LNS) metaheuristic solution approach and used the weighted sum method to deal with the bi-objective nature of the problem. Carosi et al. [

134] looked at vehicle scheduling and timetabling and used the weighted objective function to prove that the integrated timetabling and vehicle scheduling problem is a bi-objective problem. Furthermore, they proposed a multicommodity-flow-style mixed-integer linear programming model to balance service providers’ costs and customer satisfaction optimally. In another paper, Guihaire and Hao [

135] suggested an iterative local search method to solve the integrated timetabling and vehicle scheduling (ITTVS) problem. The objectives of the problem were minimizing the operational costs of vehicles and maximizing the service quality. The latter objective was measured by evenness of headways, and the former was calculated with respect to the lengths of the deadhead trips and fleet size. Schmid and Ehmke [

136] addressed the ITTVS problem with a degree of flexibility to change the timetable and balanced departure times and solved it based on the large neighborhood search (LNS) approach. The two objectives were improving the quality of timetable and reducing the operating costs, which were optimized using the weighted sum approach.

Another strategy is using the Pareto front. This strategy aims to find the Pareto optimal front, which any other solutions would not dominate. Ibarra-Rojas et al. [

137] solved timetabling and vehicle scheduling individually by introducing two integer linear programming formulations. Then, they combined the two problems into a bi-objective integrated problem. The method used to deal with this bi-objective model was based on the epsilon constraint method. The authors believe that their proposed model and solution approach could solve the problem for up to 50 bus lines. A combination of timetabling and VS was also suggested by Weiszer et al. [

138] in 2010. The suggested model included two objective functions: minimizing passengers’ waiting times at each bus stop and minimizing the required number of buses to cover all the trips mentioned in the timetable. Finally, the authors solved the problem by proposing a NSGA-II optimization technique. Liu and Ceder [

139] studied the impact of schedule deviations on public transport users’ routing choices. They developed a collaborative approach for timetabling, vehicle scheduling, and demand assignment simultaneously. For the electric buses, Teng et al. [

90] addressed the single-line bus timetabling and vehicle scheduling problem by proposing a multi-objective particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm. This paper aims to minimize the number of electric buses, and simultaneously, their charging cost.

Bi-level programming solves the problem in two different stages: leader and follower. Leaders optimize their objective regardless of followers’ objective; then, followers solve the problem and optimize their objective function based on the output of the first stage optimization of leader. Liu and Ceder [

140] proposed a bi-level integer programming model that considers the interests of public transport users and service providers to optimize the public transport timetable integrated with vehicle scheduling. A novel deficit function (DF)-based sequential search method is proposed to solve the problem and obtain Pareto fronts. Liu et al. [

141] formulated an integer programming model to address integrated bus timetabling and vehicle scheduling. Their research aimed to minimize the number of vehicles required for the total trips and maximize the number of vehicles that arrived simultaneously at the transfer nodes. This bi-objective model was solved based on a two-stage deficit function approach to generate Pareto optimal fronts. It is worth mentioning that the last two papers showed how changes in bus timetable and even vehicle scheduling could affect passengers’ trip mode choice. Liu and Shen [

142] presented a bi-level programming formulation to solve bus timetabling and vehicle scheduling. At the first level, the number of required vehicles to assign to each trip is minimized. Then, at the second level, passengers’ transfer time in connection stops is minimized concerning the solution from the first level.

The last strategy is reordering, which means considering public transportation planning as one integrated problem. Michaelis and Schöbel [

143] considered four stages of a public transportation planning system as one integrated problem. The four stages were: network design (line planning), timetabling, vehicle scheduling, and crew scheduling. The authors proposed new order for the public transportation system planning. First, the vehicle routes are designed; in the second stage, the designed routes should be split into bus lines; and in the final stage, a periodic timetable should be assigned for each line. Pätzold et al. [

144] proposed three ways to include VS in different planning stages of public transportation systems, such as timetabling and line planning. The research aimed to consider three ways to “look ahead” of planning to decrease operational costs. The complete integration of electric bus scheduling and crew scheduling was studied by Perumal et al. [

145]. The column-generation method was used to find the best vehicle and crew schedule regarding operational costs.

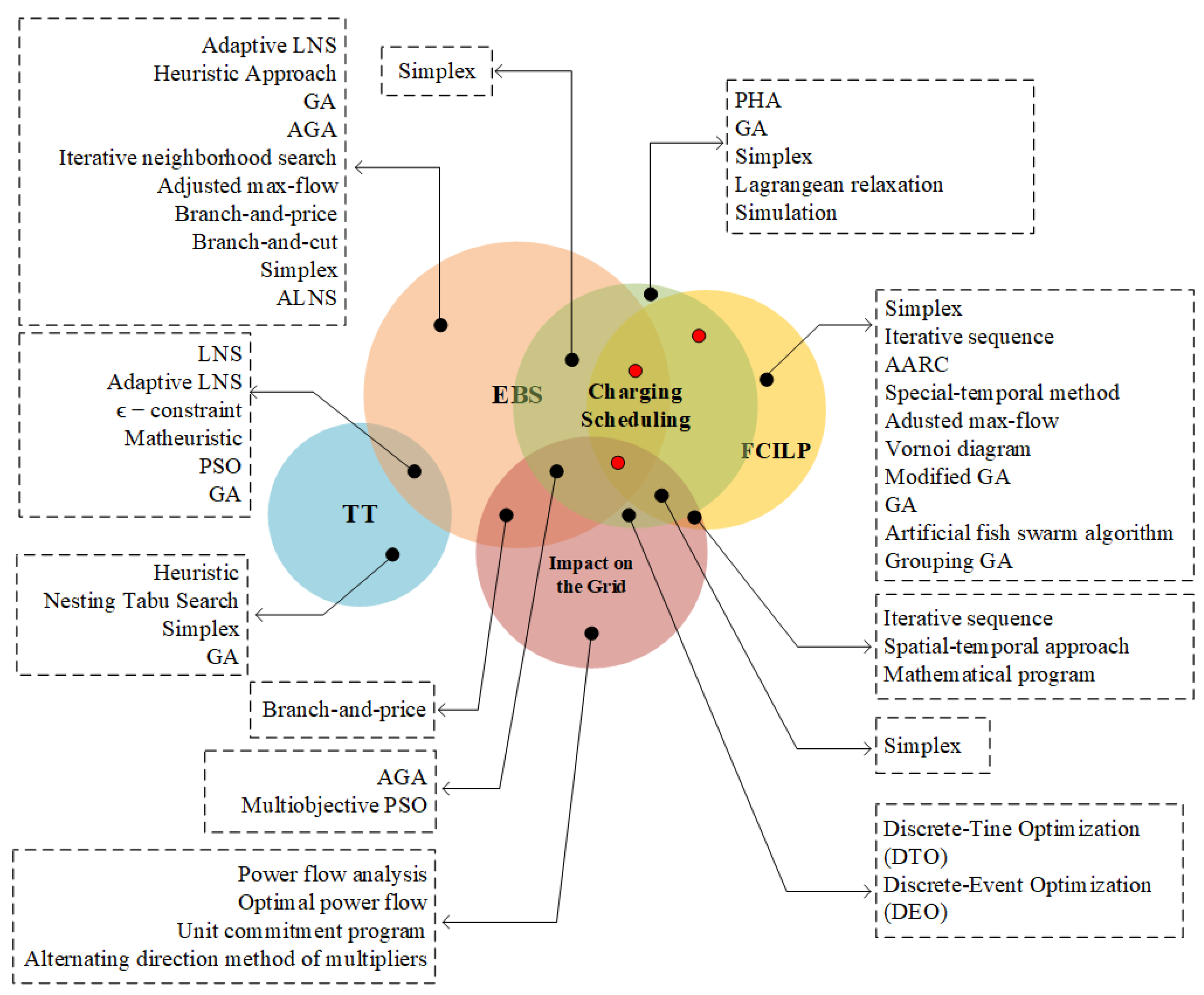

Table 6 represents an overview of the objective functions of various studies on bus scheduling and timetabling. This table shows the potential research areas for future studies regarding simultaneous optimization of bus scheduling and timetabling objectives. Additionally, we can conclude that there is a significant lack of research on integrating electric bus scheduling and charging TOU and combined optimization of EBS and timetabling.

Table 7 represents the method and algorithms adopted to solve electric bus scheduling and timetabling problems. The table shows that the number of studies using exact solution methods is remarkably less than the number papers using heuristic or metaheuristic solution approaches. Although EBS with multiple depots is an NP-hard problem, there is a research gap in reformulating such problems and solving them by the exact methods.

Table 8 shows the advantages and disadvantages of methods used for the bus scheduling and timetabling and the accuracy of the results obtained by such methods.

3.5. Impact on The Power System

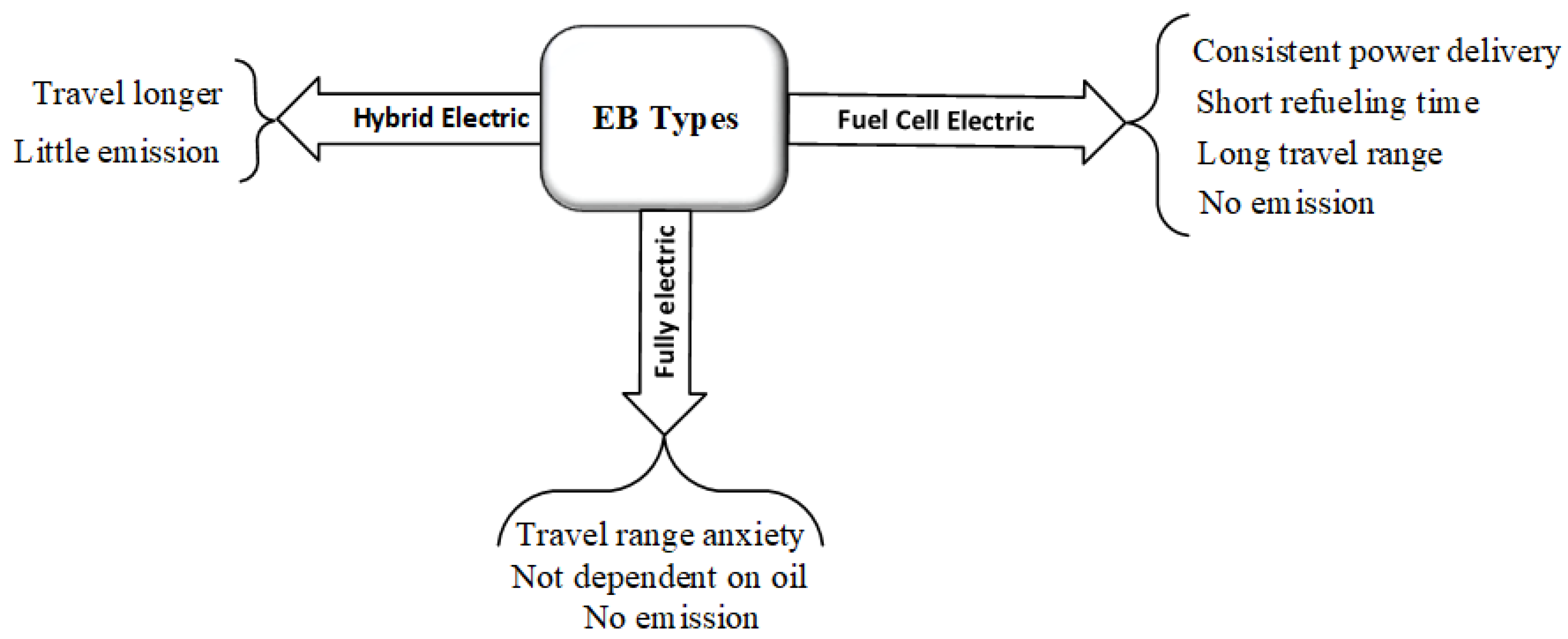

Electric buses present both challenges and opportunities for the future power network due to their size and flexibility. One such challenge is charging the electric buses’ batteries [

147]. The primary attributes of EBs include a battery capacity greater than 200 kWh, charging power greater than 40 kW, and a driving range of 200 km [

148]. Benefit-wise, EBs are superior to private EVs. They enable large passenger transfers, saving space on the road and using less energy. The basic structure of fast charging infrastructure for charging buses includes an AC/DC power converter, a transformer, a distribution grid, and its connection, as shown in

Figure 5. Transformation from the conventional buses to electric buses will have a significant impact on the electric grid. An electric bus depot which has hundreds of buses will have a severe impact on the power grid [

149]. Therefore, it is very high important for both the power utilities and transportation companies to quantify electric buses’ power demand and their impact on distribution grid. The power grid can face huge stress due to the uncoordinated charging of EBs [

150]. On the other hand, coordinated charging can deliver excessive benefits, such as valley filling and peak clipping [

151]. EVs for public transportation, such as electric buses, have received little attention so far. Due to their high-power consumption and rigorous charge times, EBs in particular present unique charging-related issues. Additionally, the battery capacities of EB used for public transportation are very high (150–450 kW), greater than that of electric cars, and the charging power is also several times greater than that of electric cars [

152]. As a result, high energy consumption and detrimental effects on power distribution networks may result [

153]. As electric transportation increases, the electricity demand required to charge their batteries will also increase.

3.5.1. Impact on the Distribution Grid

System security around the integration of EVs and EBs is receiving a lot of attention due to the high charging power of EVs and EBs. As a result, the majority of existing publications concentrate on the effective analyses of them on the distribution network. They consider the objective operations pertaining to system operation, such as power market participation [

154], grid loss minimization [

155], and network security [

156]. The high penetration of electric transportation deployment can cause different problems in the power system, such as increased peak demand, voltage drops, degrading the power quality, blackouts, and power system losses, as shown in

Figure 6. Leou and Hung [

153] established a mathematical model and tested it for a small bus fleet of 10 buses in order to take into account the charging scheduling of electric buses for the central depot. This strategy schedules bus charging based on time-of-use rates in an effort to reduce energy costs. The EB fleet’s impact on the grid’s charging, which results in overloading of the distribution transformer [

157], and more crucially, the necessity for buses to wait until off-peak hours to be charged, was not considered by the author. In [

158], the effects of the EB charging demand on the local grid and distribution were investigated on a substation in Warsaw, Poland. In [

159], two case studies employing a technique for predicting the energy and charging needs of electrified public transit are reported. By analyzing their actual, comprehensive energy use, the authors of [

160] proposed a battery-sizing methodology for several electric bus services. There are two ways to mitigate the impact of the increasing penetration of electric transportation on the power system. The first one is a direct approach, where the power system operator can directly control the charging and discharging of electric vehicles by using different charging algorithms [

161]. Such a method will benefit the power system operation and the consumer. The second method is to indirectly control the charging and discharging behavior of the consumer using demand–response programs, such as time of use pricing or real-time pricing [

162]. Such an approach will compel the consumer to use the off-peak hours to charge his electric vehicle by providing low prices for off-peak hours and high for peak hours. However, the second method might have a rebound peak if everyone uses a low pricing peak to charge their electric vehicles.

Within a smart grid, EVs, including EBs, will use optimal charging scheduling for flattening the load profile of the electrical system [

163]. In order to address the issue of coordinated charging over day-ahead scheduling, various mathematical models have been proposed and developed, such as linear and mixed-integer linear models, which focus on minimizing EV load deviation [

164], total loss minimization [

165], and charging cost minimization [

166]. One study [

167] used data gathered from automated vehicle location (AVL) in the BusGrid system to forecast future passenger demand at bus stops and in routes using supervised machine learning techniques. This improved the design of new routes and improved bus scheduling. BusGrid is an information system for enhancing customer satisfaction and productivity in public transportation bus services. BusGrid works with an operator to enhance bus timetables and develop new bus routes and stops based on anticipated demand by receiving and processing real-time data from sensors put on a bus fleet called AVL and automatic passenger counting (APC). A passenger-demand forecasting model created especially for bus networks is provided in [

168]. In this study, a time-series forecasting method was used to present a weighted ensemble prediction model that correctly forecasts bus demand for a P-minute time window using data from two Poisson models and an auto-regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model. According to [

169], AVL data were used with machine learning clustering techniques to improve the performance of the AVL system for determining bus schedules in Portugal. This connection made it easier to determine whether a schedule adjustment will satisfy the needs of the network. In a different study [

170], the authors proposed employing machine learning methods such as unsupervised clustering to identify trends among AVL data in order to enhance Sweden’s public transportation timetables. Other objectives have also been taken into account, including reducing the loss of electricity to the grid, EV battery degradation, reducing

emissions, and increasing the level of satisfaction among EV owners [

171]. A new business paradigm is being facilitated by the rise in EVs and EBs, and the inclusion of renewable energy resources in the future power network [

172]. For the introduction of EBs in power systems, several researchers created novel approaches with a variety of primary goals. Electric bus energy estimation has been studied by some writers. Stochastic modeling and forecasting of load demand of EB battery swap station are studied in [

173]. Fuzzy clustering and least-squares support vector machines optimized by the Wolf pack method were used to forecast EB load over the short term [

174]. The optimization of the EB aggregator will minimize charging costs while satisfying a variety of electrical constraints to optimize the charging load during the charging process. The optimization problem considering the minimizing the daily charging cost of EBs is as

Appendix A.1 [

148].

Thiringer and Haghbin [

175] investigated the effect of EVs (including electric buses) on the substation reserves in order to address the power quality issue in a fast-charging station. The case study used in this work was based on real electric bus data from Gothenburg, Sweden. This study examined potential problems with the effect on the electrical system but did not make recommendations for how to improve the charging schedule. Zoltowska and Lin [

176] used aggregated day-ahead auction bids to plan the charging schedule of EBs for minimizing the cost of charging scheduling. Using the market participation idea, an optimization model for coordinated charging of the bus fleet and fast-charging stations was created in this study. There are many optimization techniques for battery switching [

177], and there is the flash wireless charging concept for bus timetables [

178]. Different studies have evaluated the impact of electric transportation on the distribution voltage by implementing the optimal charging strategy with the operation constraint on the distribution network [

179,

180]. The author in [

181] proposed the Monte Carlo approach to assess the effect of electric transportation charging on the voltage imbalance level and calculate the voltage quality. In [

182], other factors of the distribution system, such as, but not limited to, feeder losses, variation in the load, and load factor, were analyzed with an optimal charging algorithm. In [

183], the author compared the impacts of electric-vehicle charging on European and North American distribution systems. These voltage drops on the distribution system can be mitigated by installing an additional transformer, but it is expensive and needs infrastructural changes.

3.5.2. Impact on the Transformer

Electricity is typically supplied via liquid-fill and dry-type transformers in distribution systems. The power rating of such a transformer often varies by country, ranging from a few kVA to hundreds of thousands of kVA. For instance, the power rating utilized on 11 and 22 kV networks in Australia ranges from 10 to 2500 kVA [

184]. The price of a transformer varies from hundreds of dollars to several hundred thousand dollars depending on the brand, quality, size, and kind. According to [

185], EVs are not taken into account while sizing distribution transformers in conventional power systems. As the penetration of EVs rises, the demand on the transformers will peak as a result of charging such a large battery bank. It will result in extreme voltage drops, increased power losses, and a shorter lifespan for the transformers.

Due to the existence of EBs uncoordinated charging, distribution system operators and transmission system operators (TSO) may experience difficulties in the future. All of these issues must be handled by DSO and TSO using all of the resources at their disposal. The EV aggregator is now a required partner who gives the DSO and TSO technical services [

186]. The aggregator will serve as a middleman between operators, who will likely make use of market mechanisms to acquire the required assets and EB stations. Such an aggregator can be implemented on the distribution transformer, as distribution transformers are susceptible and costly devices in the distribution system. This will also help the distribution transformer to reduce losses and damage cost due to peak load of buses. The EB aggregator transformer will provide its services to TSO and DSO for grid operations, and maybe to other electricity partners to optimize their energy portfolio purchases. According to a survey, the most significant share in the distribution network is the new installation of the distribution transformer [

187]. The peak demand on the transformer side will indirectly raise the temperature that causes the so-called accelerated ageing of the transformer insulation as the penetration level of electric vehicles rises [

188].Such an aging effect may cost billions of dollars to the power system utilities [

189]. Ahmadian et al. [

190] studied the effect of EV charging on the traditional system, which results in voltage profile violation. The authors ideally distributed and designed the shunt capacitor and the wind-based distributed generation (DG) across the system, considering the load variability of the EVs and DGs in relation to the system voltage profile. They also used a short-schedule decision for the load tap changer (LTC) tap setting of the transformer. Azzouz et al. [

191] took into account the high penetration of EVs and DGs in an attempt to reduce voltage variation and LTC tap operation, maximize the EVs delivered power, and optimize the power captured by the DGs. The high penetration level of the electric transportation (specifically electric buses) will cause problems on the transformer, including but not limited to decreasing the life-time of transformer, overloading the transformer, and increase power losses on the transformer, as shown in

Figure 6 [

192].

It is now understood that if the high penetration of electrification of the transport system is not correctly managed, it will cause a severe impact on the distribution system and grid side.

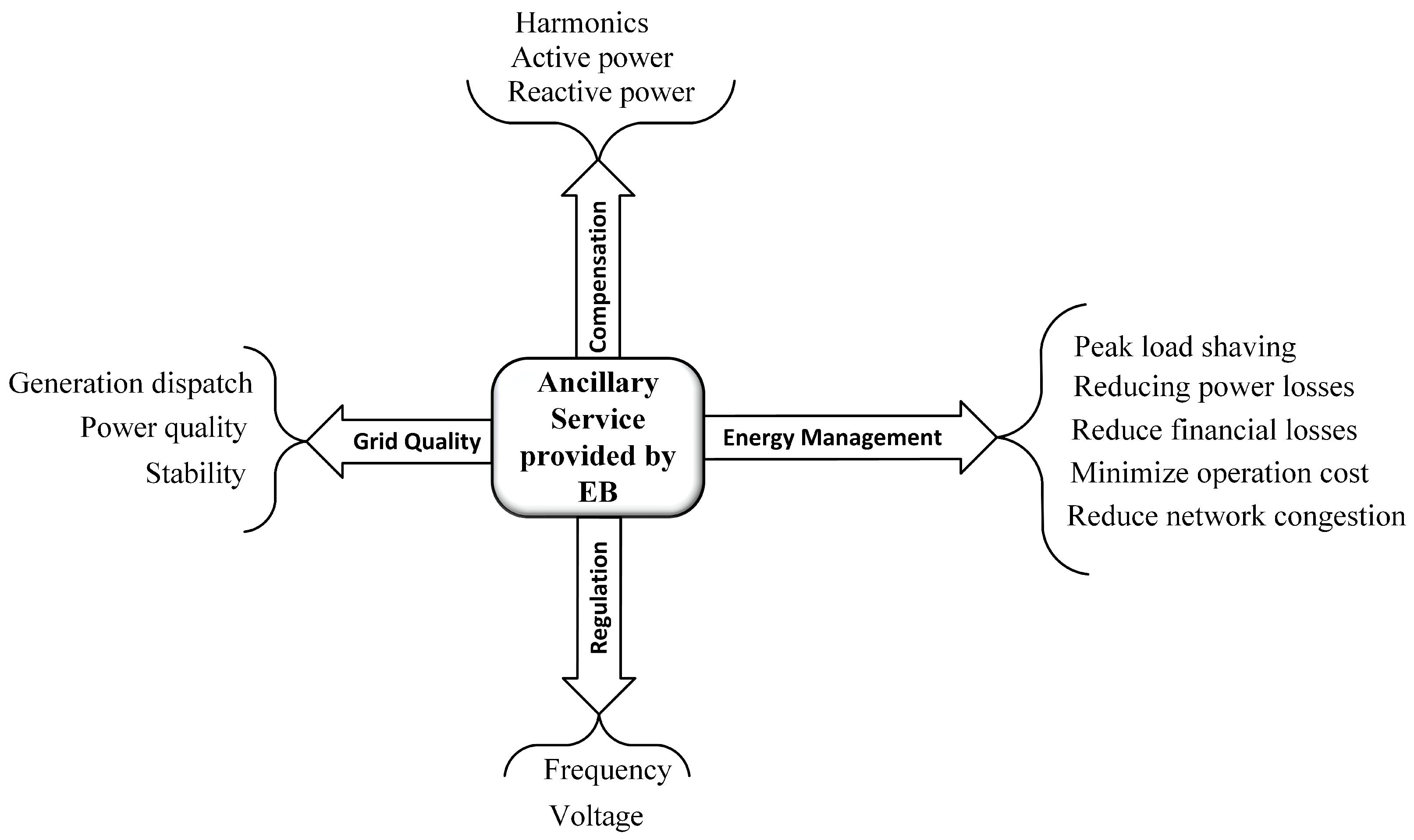

3.5.3. Ancillary Service by Electric Buses

According to [

193], uncoordinated charging overloads the transformer and transmission line. EB charging can be categorized as unidirectional or bidirectional depending on the direction of the energy flow [

194]. In unidirectional charging, power is sent from the grid to the EB acting as a load in the power system. The control of EV charging during unidirectional and controlled charging should aim to reduce peak demand. A bidirectional AC/DC converter is used by EVs to support energy transfer between the grid and the vehicle in both directions. There are two types of bi-directional power flow, that is, grid-to-vehicle (G2V), in which power is sent to the EV, and vehicle-to-grid (V2G) and vehicle-to-home (V2H), in which the EV serves as an ESS and feeds power into the grid [

195]. Controlled and uncontrolled charging are further categories. The uncontrolled charging is done improperly and without the use of any control optimization techniques, which results in supply and demand imbalances, undesirable and unexpected peaks on the distribution system, increased voltage deviations, increased power losses, and decreased reserve margins [

196]. In several studies, the V2G mode was taken into account, which is described as the EV’s capability to charge its batteries and give electricity to the grid, resulting in a bidirectional flow between the grid and the EV [

197]. As shown in

Figure 7, EBs can offer ancillary services to the power grid using various modes of operation, for instance, by improving grid quality through increasing the stability and generation dispatch. Providing improved energy management is also important, and can be accomplished through such things as peak shaving, reducing operation losses, and minimizing the cost. Such ancillary services also improve and regulate the voltage and frequency of the distribution network. The bank of batteries can also provide active power to the grid. The authors of [

198] suggest intelligently charged electrified transit by taking into account V2G for EBs to assist renewable energy sources in the Austin power grid. Reference [

199] proposed a charging approach for quick-charging stations that was based on a decision-making procedure and held the stance that the EBs only paid under the quick-charger load limit. The best location for fast-charging stations with an energy storage system to maximize the financial advantages was investigated in [

200,

201]. The authors of [

202] investigated multi-external aspects in EB scheduling.

Even if EVs improve the grid in a variety of ways, if the penetration level rises significantly, this negatively impacts the distribution transformer and distribution system. The bidirectional charger consumes EV load, which introduces harmonics into the system and degrades the power quality. Additionally, significant upgrading of the current communication and distribution networks is required for the adoption of a bidirectional charger. On the other hand, it is still challenging to assess how much EVs actually participate in electricity markets. It is challenging to assume these activities for EBs given the economic viability of V2G mode. Additionally, due to driving schedules, EBs are less flexible than light EVs. However, given their limited number, high charging power rate, and ability to charge in public locations, EBs are more easily aggregated.

In a nutshell, it is acknowledged that substantial EB implementation across the distribution system can dramatically increase load demand if EB charging and discharging infrastructure is not handled effectively. It will result in the grid’s generational capacity being increased.