Transport Preferences of City Residents in the Context of Urban Mobility and Sustainable Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Improving traffic flow in cities by optimizing the use of private cars, promoting active mobility (walking, cycling), suistainable commercial transport;

- Improving accessibility and integration of urban transport, including sustainable spatial planning;

- Increasing the use of Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) services in urban transport;

- Reducing the negative impact of transport on the environment by using modern technologies and alternative energy sources, promoting eco-driving and limiting car traffic;

- Improving the safety and reliability of urban transport;

- Changing transport behavior and the way that transport is perceived by urban communities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Communication Preferences

2.2. Urban Mobility and Technologies, That Conducive It

2.3. The Car as the Dominant Mean of Transport

- Population mobility, including mobility as a necessity, will and right to move, and impact on the development of transport and road traffic;

- Development of the automotive industry and its consequences for medium-sized cities;

- Transport policy;

- Road transport in the context of urban ecology, spatial policy and development planning.

2.4. Sustainable Development of Urban Transport

- On-board equipment for FMS, ticketing and CCTV, with an integrated control center for 290 buses and 150 trams:

- -

- High-performance OBU for FMS, ticketing and CCTV management;

- -

- 1686 validators for Transport Smart Cards;

- -

- 300 on-board TVMs;

- -

- 1125 on-board video surveillance cameras.

- Passenger Information System:

- -

- On-board multimedia information system;

- -

- 99 information displays at stops;

- -

- Internet and applications.

- 36 TVM at stops:

- Passenger Counting System;

- Request stops.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Scope

- Determine how travel is related to destination;

- Indicate the dependence of the chosen means of transport on age, education, professional activity, industry and place of residence;

- Clarify the restrictions on the freedom of choice and access to means of transport, which affect residents’ mobility, quality of life and the implementation of sustainable development provisions;

- Obtain information about the residents’ motivations when choosing their means of transport, depending on the specific destination and based on the indicated factors (economic, ecological, own comfort and safety, and congruence with the principles of sustainable development and quality of life).

- Hypothesis: The analysis of the obtained results allows for the relationship between the declared manner of the respondents’ movement and their needs in the area of mobility and awareness of changes consistent with the principles of sustainable development to be observed.

3.2. Research Area

3.3. Characteristics of the Method—Identification of User Preferences in Terms of Moving around the City

- How often do you use a given means of transport?

- How do you evaluate the level of safety in the moving means of transport?

- How do you evaluate the level of accessibility to means of transport?

- In what directions and how do you move?

- What kind of limitations reduce access to means of transport?

- What features do you think the means of transport should have?

- What extent to does the way you get around the city affect your daily life?

- What is your way of moving around the city conditioned?

- Principles of sustainable development;

- Quality of life;

- Economic factors;

- Ecological factors;

- Own comfort and safety;

- Other.

3.4. Analysis of the Declared Transport Preferences

4. Results

- Respondents’ preferences with regard to means of transport to a specific activity;

- Determining the reasons for respondents’ choice of transport;

- Identification of limitations regarding respondents’ chosen means of transport in the surveyed directions.

4.1. Analysis of the Respondents’ Chosen Means of Transport in the Indicated Directions of Movement

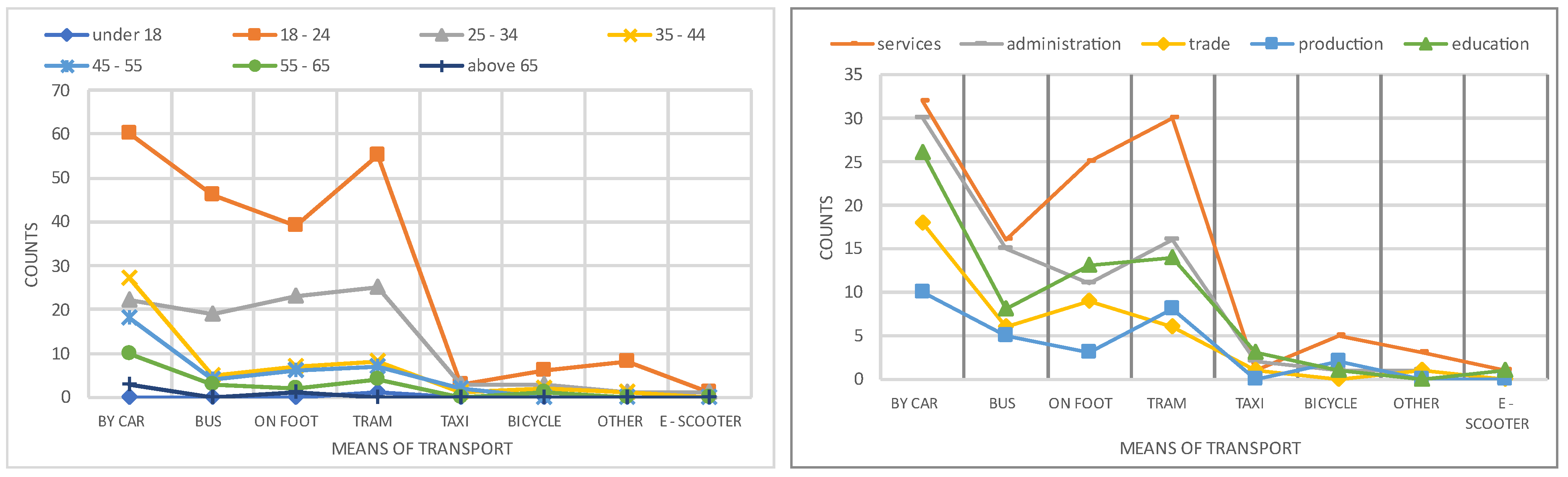

- Szczecin residents chose to use the bus less frequently than other identified respondents, similar to the case of professionally active people;

- Students choose trams more than other groups;

- Service workers also choose trams more often than other industries;

- Workers in trade, however, chose trams less often than other groups, and more often travelled on foot;

- People with secondary education use buses more than other groups;

- Men decide to travel by bike more often than women;

- For people aged 25–34, the car ranked third, after travelling by tram and on foot, but for the other age groups, the car was the most frequently used means of transport;

- Hiking trips were chosen less often by respondents aged 18–24 than by other groups, as shown in Figure 4.

- For most age groups, a car is used for travelling; only the age group 18–24 use walking trips;

- Professionally active people choose a car more often; students usually travel on foot;

- Respondents with higher education travel by car more often, while respondents with secondary education travel on foot;

- People living in Szczecin first chose to travel on foot and by car, and then by tram; respondents from the vicinity of Szczecin mainly use a car, and the remaining respondents travel by foot and by car;

- Women choose to travel on foot, as opposed to by car, more often than men.

- For the 34–44 and 45–55 age groups, the main means of transport is by car; for the other age groups, it is on foot;

- Professionally active people choose to travel by car more often, and students travel on foot;

- All industries, apart from administration, choose pedestrian trips first, then the car; administration industries first travel by the car and then on foot;

- Respondents with higher education use trams much less;

- Women use cars less.

4.2. Motivation Analysis

- The principles of sustainable development (SDP);

- Own comfort and safety (OCS);

- Economic factors (EF);

- Ecological factors (EcF);

- Quality of life (QL);

- Other, not mentioned factors (O).

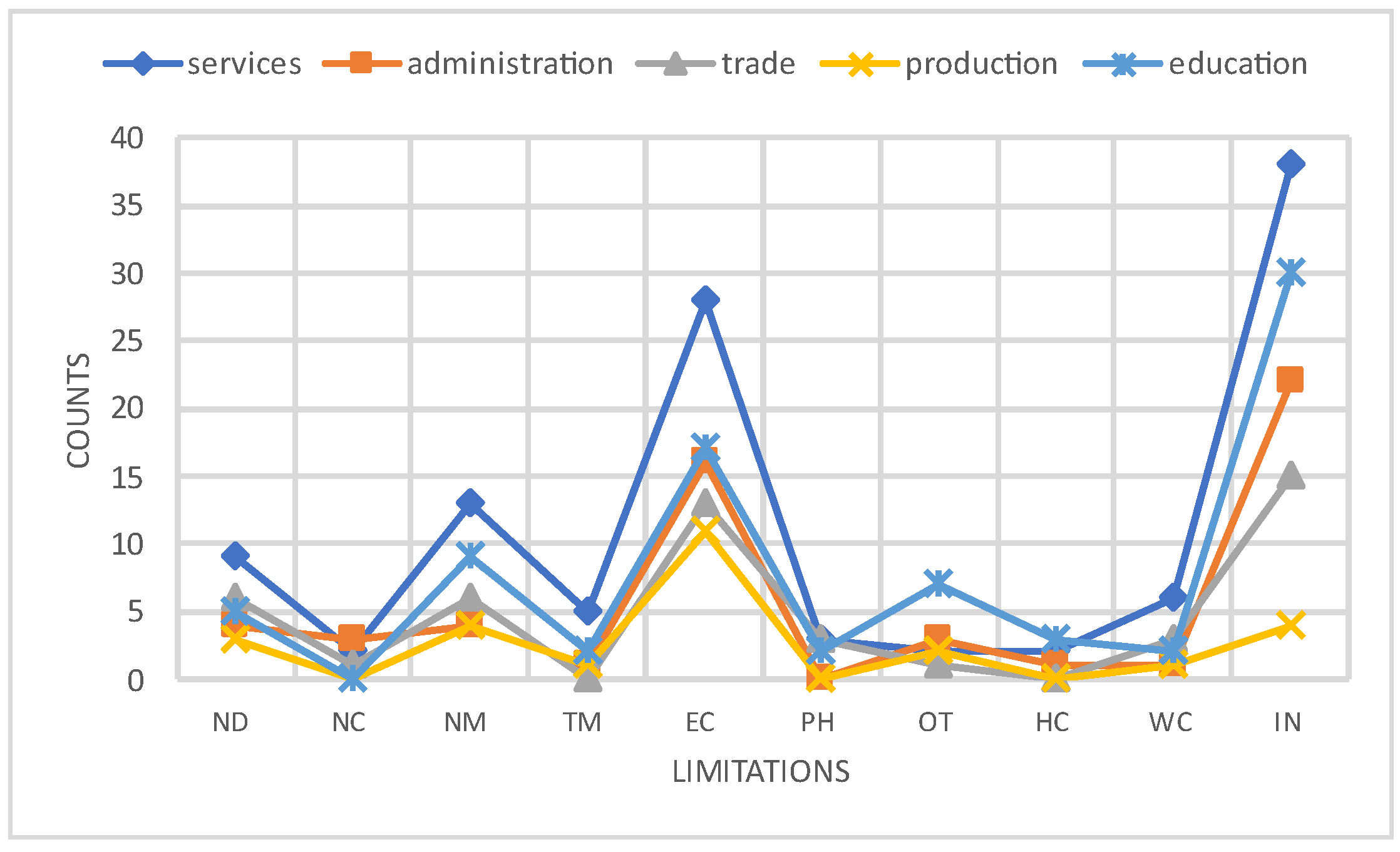

4.3. Analysis of Limitations regarding Respondents’ Chosen Means of Transport in the Surveyed Directions

4.3.1. Restrictions for the Car

4.3.2. Bus Restrictions

4.3.3. Tram Restrictions

5. Discussion

5.1. The Dominant Role of the Car

5.2. Identification of Preferences regarding the Chosen Means of Transport Depending on the Respondents’ Characteristics

5.3. Identification of Accessibility Restrictions for Individual Means of Transport

6. Conclusions

- Monitoring the availability of ecological means of transport;

- Assessing of the possibility of using an ecological means of public transport;

- Comparing data on means of transport with ITS with those obtained from previous surveys;

- Assessing the preferences of urban transport users in other Polish cities for comparison;

- Researching additional forms of transport.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation Systems |

| LED | Light-Emitting Diode |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PSPA | Polish Alternative Fuels Association (Polskie Stowarzyszenie Paliw Alternatywnych) |

| PZPM | Polish Automotive Industry Association (Polski Związek Przemysłu Motoryzacyjnego) |

| SDP | Sustainable Development Principles |

| SRM | Szczecin City Bike (Szczeciński Rower Miejski) |

| ZDiTM | Road and Public Transport Authority in Szczecin |

References

- European Commission. White Paper on Transport (2011) Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area–Towards a Competitive and Resource Efficient Transport System; COM (2011) 144 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Kirby, A. CCCC Kick the Habit, A UN Guide to Climate Neutrality; UNEP: Arendal, Norway, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency, European Union Emission Inventory Report 1990–2016. 2018. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/european-union-emission-inventory-report-1 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Annual Energy Review, 2011; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- European Commission DG MOVE. Study to Support an Impact Assessment of the Urban Mobility Package; Activity 31 Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans Final Report; European Commission DG MOVE: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- COM (2013) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council of the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM/2013/0913. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52013DC0913&from=EN (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Commission of the European Communities. Green Paper. Towards a New Culture for Urban Mobility; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2007.

- OECD/ECMT. Managing Urban Traffic Congestion. Paris. 2007. Available online: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/transport/managing-urban-traffic-congestion_9789282101506-en (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Grzelec, K. Organizational conditioning of passenger urban transport development. Transp. Miej. I Reg. 2020, 2, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Starowicz, W. Jakość Przewozów W Miejskim Transporcie Zbiorowym; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2007; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bryniarska, Z.; Starowicz, W. Funkcjonowanie systemu statystycznej kontroli jakości usługi transportowej w Krakowie w latach 1997–2005. Transp. Miej. I Reg. 2006, 12, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ciastoń-Ciulkin, A. Quality criteria applied in the contracts for transport services in big cities and methods of its controlling, Transp. Miej. I Reg. 2013, 4, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ustawa o publicznym transporcie zbiorowym z dnia 16 grudnia 2010 r., Dz. U. z 2011 r. Nr 5, poz. 13, Nr 228, poz. 1368. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20110050013/T/D20110013L.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Druckman, J.N.; Lupia, A. Preference formation. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2000, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Słownik Języka Plskiego PWN. Available online: https://sjp.pwn.pl/sjp/preferencja;2572329.html (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Abou-Zeid, M.; Schmöcker, J.D.; Belgiawan, P.F.; Fujii, S. Mass effects and mobility decisions. Transp. Lett. 2013, 5, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugundji, E.R.; Páez, A.; Arentze, T.A.; Walker, J.L.; Carrasco, J.A.; Marchal, F.; Nakanishi, H. Transportation and social interactions. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2011, 45, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plan Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Publicznego Transportu Zbiorowego Dla Miasta Szczecin Na Lata 2013–2025. Available online: http://bip.um.szczecin.pl/UMSzczecinFiles/file/Plan_Zrownowazonego_Rozwoju_Publicznego_Transportu_Zbiorowego_Szczecin_KONSULTACJE.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Garikapati, V.M.; Pendyala, R.M.; Morris, E.A.; Mokhtarian, P.L.; McDonald, N. Activity patterns, time use, and travel of millennials: A generation in transition? Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 558–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, A.; Börjesson, M.; Eliasson, J. Explaining “peak car” with economic variables. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2016, 88, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsafarakis, S.; Gkorezis, P.; Nalmpantis, D.; Genitsaris, E.; Andronikidis, A.; Altsitsiadis, E. Investigating the preferences of individuals on public transport innovations using the Maximum Difference Scaling method. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2019, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorio, C.V.; Florio, M.; Perucca, G. User satisfaction and the organization of local public transport: Evidence from European cities. Transp. Policy 2013, 29, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salih, W.Q.; Esztergár-Kiss, D. Linking Mode Choice with Travel Behavior by Using Logit Model Based on Utility Function. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, G.; Arbolino, R.; Shi, L.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Ioppolo, G. Digital Technologies for Urban Metabolism Efficiency: Lessons from Urban Agenda Partnership on Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, M.H.; Møller-Jensen, L. Access to the city: Mobility patterns, transport and accessibility in peripheral settlements of Dar es Salaam. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 62, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sepasgozar, S.M.; Hawken, S.; Sargolzaei, S.; Foroozanfa, M. Implementing citizen centric technology in developing smart cities: A model for predicting the acceptance of urban technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneć, R. The role of stakeholders in shaping smart solutions in Polish cities. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 1981–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogall, H. Ekonomika Zrównoważonego Rozwoju. Teoria i Praktyka; Zysk i S-ka: Poznań, Poland, 2010; pp. 88–120. [Google Scholar]

- Adamkiewicz-Kłos, Z.; Załoga, E. Miejski Transport Zbiorowy. Kształtowanie Wartości Usługi Dla Pasażera W Świetle Wyzwań Nowej Kultury Mobilności; BelStudio: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; pp. 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Madeyski, M. Some aspects of the mobility of population and its satisfaction. Int. J. Transp. Econ. 1974, 1, 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Badania Pilotażowe Zachowań Komunikacyjnych Ludności Polsce. Raport Końcowy; Centrum Badań i Edukacji Statystycznej GUS: Jachranka, Poland, 2015; p. 5.

- Bidasca, L. European Commission Sustainable Urban Mobility–Policy & Key Actions; JRC Community of Practice, Research and Innovation/Urban Mobility; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 28 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cordera, R.; Coppola, P.; dell’Olio, L.; Ibeas, Á. Is accessibility relevant in trip generation? Modelling the interaction between trip generation and accessibility taking into account spatial effects. Transportation 2017, 44, 1577–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Izba Gospodarcza Komunikacji Miejskiej. Available online: https://igkm.pl/statystyka/ (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Hull, A. Transport Matters. Integrated Approachesto Planningcity–Regions; Publisher Routledge. Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2011; pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, V.; Kesseliring, S. Tracing Mobilities. Towards a Cosmopolitan Perspective; Ashgate: Hampshire, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- An Integrated Perspective on the Future of Mobility; McKinsey Centre for Future Mobility. McKinsey & Company: Hong Kong, China, 2016.

- Bouton, S.; Knupfer, S.M.; Mihov, I.; Swartz, S. Urban Mobility at a Tipping Point; McKinsey & Company: Hong Kong, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aapaoja, A.; Eckhardt, J.; Nyk¨anen, L.; Sochor, J. MaaS service combinations for different geographical areas. In Proceedings of the 24th World Congress on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 29 October–2 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Future of transport. Analytical Report. Flash EB 312, The Gallup Organizations; EMTA Barometr 2013, Consortio Transports, Madryt 2015; Europen Commissione: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Oskarbski, J.; Birr, K.; Żarski, K. Bicycle Traffic Model for Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning. Energies 2021, 14, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.W. Current Systems in Psychology: History, Theory, Research and Applications; Thomson Learning: Wadsworth, OH, USA; Belmont, NC, USA, 2001; pp. 45–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brůhová Foltýnováa, H.; Vejchodskáa, E.; Rybováa, K.; Květoňb, V. Sustainable urban mobility: One definition, different stakeholders’ opinions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 87, 102465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Kadir, S.A.; Aziz, A.; Mokshin, M.; Lokman, A.M. Aplikacja mobilna I Tourism travel buddy. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Next Generation Mobile Applications, Security and Technologies (NGMAST), Cardiff, Wales, 24–26 August 2016; pp. 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.; Brand, C. Assessing the potential for carbon emissions savings from replacing short car trips with walking and cycling using a mixed GPS travel diary approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 123, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora-Fernandez, D. Smarter cities in post-socialist country: Example of Poland. Cities 2018, 78, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempp, M.; Siegfried, P. Conclusion to Automotive Disruption and the Urban Mobility Revolution. In Automotive Disruption and the Urban Mobility Revolution. Business Guides on the Go; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebe, U.D.; Hick, H.; Rothbart, M.; von Helmolt, R.; Armengaud, E.; Bajzek, M.; Kranabitl, P. Challenges for Future Automotive Mobility. In Systems Engineering for Automotive Powertrain Development. Powertrain; Hick, H., Küpper, K., Sorger, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, M.; Marinelli, M. Sustainable Mobility: A Review of Possible Actions and Policies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klecha, L.; Gianni, F. Designing for Sustainable Urban Mobility Behaviour: A Systematic Review of the Literature. In Citizen, Territory and Technologies: Smart Learning Contexts and Practices, Smart Innovation; Mealha, Ó., Divitini, M., Rehm, M., Eds.; Systems and Technologies 80; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Polacy W Czołówce Europejskiego Rankingu. Powodu Do Dumy Nie Ma. Available online: https://smoglab.pl/liczba-samochodow-na-1000-mieszkancow/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- ACEA Report. Vehicles in Use Europe 22. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/files/ACEA-report-vehicles-in-use-europe-2022.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Polish EV Outlook 2022–Raport, Polskie Stowarzyszenie Paliw Alternatywnych. Available online: https://pspa.com.pl/2019/informacja/uruchomiono-polski-licznik-elektromobilnosci/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Raport CSR.PL. Available online: https://raportcsr.pl/licznik-elektromobilnosci-w-2021-r-na-polskie-drogi-wyjechalo-ponad-20-tys-aut-z-napedem-elektrycznym/ (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Plakietki Ekologiczne W Europie. Przepisy, Ceny, Kary. Available online: https://motofakty.pl/plakietki-ekologiczne-w-europie-przepisy-ceny-kary/ar/c4-16271325 (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Strulak-Wójcikiewicz, R.; Lemke, J. Concept of a Simulation Model for Assessing the Sustainable Development of urban transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 39, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrzewska, M.; Macikowski, B. Towards Hybrid Urban Mobility: Kick Scooter as a Means of Individual Transport in the City. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 052073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Litman, T. Well Measured: Developing Indicators for Sustainable and Livable Transport Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute, Canada 2016. Available online: http://www.vtpi.org/wellmeas.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Okraszewska, R.; Romanowska, A.; Wołek, M.; Oskarbski, J.; Birr, K.; Jamroz, K. Integration of a Multilevel Transport System Model into Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning. Sustainability 2018, 10, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, X.; Ren, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, L. Intelligent Device System of Urban Transportation Service. In Proceedings of the IEEE 8th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference, ITAIC, Chongqing, China, 24–26 May 2019; pp. 1729–1732. [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko, K.; Tkachenko, O. Modeling of management of intelligent systems in transport. Transp. Syst. Technol. 2022, 39, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zear, A.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, Y. Intelligent Transport System: A Progressive Review. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.R.; Quesada-Arencibia, A.; Cristóbal, T.; Padrón, G.; Alayón, F. Systematic Development of Intelligent Systems for Public Road Transport. Sensors 2016, 16, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Intelligent System for Public Transport in the City of Szczecin (Poland). Available online: https://www.gmv.com/sites/default/files/content/file/2021/04/05/115/caso-de-exito_szczecin_eng.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Fioreze, T.; de Gruijter, M.; Geurs, K. On the likelihood of using Mobility-as-a-Service: A case study on innovative mobility services among residents in the Netherlands. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2019, 7, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towards a Sustainable Europe by 2030, Reflection Paper, COM(2019) 22; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Wytyczne Dotyczące Opracowywania i Wdrażania Planu Zrównoważonej Mobilności Miejskiej, Wyd. 2, Consult, R; Europejska Platforma Planów Zrównoważonej Mobilności Miejskiej: Kolonia, Germany, 2019.

- Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej-Państwowy Instytut Badawczy. Rocznik Meteorologiczny 2020. Available online: https://danepubliczne.imgw.pl/data/dane_pomiarowo_obserwacyjne/Roczniki/Rocznik%20meteorologiczny/ (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/start (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Act of 16 December 2010 on Public Collective Transport (Journal of Laws of 2011, No. 5, Item 13). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20110050013 (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Act of 8 March 1990 r. on Local Self-Government (Journal of Laws of 1990, No. 16, Item 95). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19900160095 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Pietrzak, O.; Pietrzak, K. The Economic Effects of Electromobility in Sustainable Urban Public Transport. Energies 2021, 14, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/dane/podgrup/tablica (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Wynajem Samochodów. Available online: https://www.kayak.pl/Tani-Wynajem-Samochodow-Szczecin.11418.cars.ksp (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Wolnowska, A.; Rymer, W. The role of city bicycles in the public transport in Szczecin. Studia Miej. 2016, 23, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Olbrzymie Zmiany w Zasadach Korzystania z Roweru Miejskiego. Za Miesiąc Startuje BikeS. Available online: https://wszczecinie.pl/aktualnosci,olbrzymie_zmiany_w_zasadach_korzystania_z_roweru_miejskiego_za_miesiac_startuje_bikes,id-40127.html (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Akademicki Szczecin. Available online: https://www.szczecin.eu/akademicki_szczecin/uczelnie_wyzsze_w_szczecinie.html (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Znajdź Uczelnie Dostosowana Do Twoich Potrzeb. Available online: https://www.uczelnie.pl (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Glaser, B.G. The Grounded Theory Perspective: Conceptualization Contrasted with Description; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 37–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R. Case Studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India, 1994; pp. 236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wolnowska, A.E.; Kasyk, L. Ways Residents of Large Cities in Poland, Commute before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 3B, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Runger, G.C. Applied Statistics and Probability for Engineers; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 154–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wiktorowska-Jasik, A. Implemented sustainable public transport solutions and social expectations for the city transport system of Szczecin. Sci. J. Marit. Univ. Szczec. 2020, 61, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C.; Masala, F.; Pinna, F. Cagliari and smart urban mobility: Analysis and comparison. Cities 2016, 56, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, G. Getting Smart About Urban Mobility: Aligning the Paradigms of Smart and Sustainable. Transp. Res. Part A 2016, 115, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawieska, J. Zachowania i preferencje komunikacyjne mieszkańców Warszawy w kontekście zmian społeczno-ekonomicznych w latach 1993–2015. Transp. Miej. I Reg. 2017, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vij, A.; Carrel, A.; Walker, J.L. Incorporating the influence of latent modal preferences on travel mode choice behavior, Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 54, 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, A.; Chodkowska-Miszczuk, J.; Rogatka, K.; Starczewski, T. Smart Energy in a Smart City: Utopia or Reality? Evidence from Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 5795. [Google Scholar]

- Taiebat, M.; Brown, A.L.; Safford, H.R.; Qu, S.; Xu, M. A Review on Energy, Environmental, and Sustainability Implications of Connected and Automated Vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11449–11465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firnkorn, J.; Müller, M. Free-floating electric carsharing-fleets in Smart Cities: The Dawning of a Post-Private Car Era in Urban Environments? Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 45, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenblatt, J.; Saxena, S. Autonomous Taxis Could Greatly Reduce Greenhouse-Gas Emissions of US Light-Duty Vehicles, Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 860–863. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.; Becker, H.; Bösch, P.; Axhausen, K. Autonomous Vehicles: The Next Jump in Accessibilities? Res. Transp. Econ. 2017, 62, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wadud, Z.; MacKenzie, D.; Leiby, P. Help or Hindrance? The Travel, Energy and Carbon Impacts of Highly Automated Vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A 2016, 86, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero, F.; Perboli, G.; Rosano, M.; Vesco, A. Car-sharing services: An annotated review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annex a Concept for Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans to the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Together Towards Competitive and Resource-Efficient Urban Mobility. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/ (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Dimitrowa, E. The ‘sustainable development’ concept in urban planning education: Lessons learned on a Bulgarian path. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krych, A. Horyzont 2050–o nowy paradygmat planowania mobilności. Transp. Miej. I Reg. 2020, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cascajo, R.; Garcia-Martinez, A.; Monzon, A. Stated preference survey for estimating passenger transfer penalties: Design and application to Madrid. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dostatni, K. Badania jakości funkcjonowania komunikacji miejskiej w Poznaniu w latach 2013-2019. Transp. Miej. I Reg. 2020, 3, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chyba, A.; Chyba, K. Punktualność kursowania pojazdów miejskiego transportu zbiorowego w Krakowie w latach 1997-20011, Transp. Miej. I Reg. 2012, 12, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Filipović, S.; Tica, S.; Živanović, P.; Milovanović, B. Comparative analysis of the basic features of the expected and perceived quality of mass passenger public transport service in Belgrade. Transport 2009, 24, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Car Rental | Number of Locations in Szczecin | Car Rental | Number of Locations in Szczecin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panek | 4 | Avis | 1 |

| Hertz | 3 | Budget | 1 |

| RENTIS | 6 | Car Net | 1 |

| Sunnycars | 4 | CarFree | 1 |

| Express Rent a Car | 3 | Dollar | 1 |

| Carrson | 2 | MWM Cars | 1 |

| Europcar | 2 | Platinum Rent a Car | 1 |

| Global Rent a Car | 2 | Thrifty | 1 |

| keedy by Europcar | 2 | US Rent-a-car | 1 |

| Right Cars | 2 | Van Fleet Poland | 1 |

| 99Rent | 1 | YouRent | 1 |

| Travel Directions/Means of Transport | On Foot | By Car | Bus | Tram | Bicycle | Taxi | E-Scooter | Electric Scooter | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home–work | |||||||||

| Work–home | |||||||||

| Home–school | |||||||||

| School–home | |||||||||

| Home–shopping | |||||||||

| Shopping–home | |||||||||

| Home–fitness | |||||||||

| Fitness–home | |||||||||

| Home–entertainment | |||||||||

| Entertainment–home | |||||||||

| Home–cemetery | |||||||||

| Cemetery–home | |||||||||

| Home–hospital | |||||||||

| Hospital–home | |||||||||

| Other than mentioned |

| Travel Directions | Abbreviations Used | Travel Directions | Abbreviations Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home–work | H-w | Home–entertainment | H-e |

| Work–home | W-h | Entertainment–home | E-h |

| Home–school | H-s | Home–cemetery | H-c |

| School–home | S-h | Cemetery–home | C-h |

| Home–shopping | H-sh | Home–hospital | H-h |

| Shopping–home | Sh-h | Hospital–home | H-h |

| Home–fitness | H-f | Other than mentioned | O |

| Fitness–home | F-h |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolnowska, A.E.; Kasyk, L. Transport Preferences of City Residents in the Context of Urban Mobility and Sustainable Development. Energies 2022, 15, 5692. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155692

Wolnowska AE, Kasyk L. Transport Preferences of City Residents in the Context of Urban Mobility and Sustainable Development. Energies. 2022; 15(15):5692. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155692

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolnowska, Anna Eliza, and Lech Kasyk. 2022. "Transport Preferences of City Residents in the Context of Urban Mobility and Sustainable Development" Energies 15, no. 15: 5692. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155692

APA StyleWolnowska, A. E., & Kasyk, L. (2022). Transport Preferences of City Residents in the Context of Urban Mobility and Sustainable Development. Energies, 15(15), 5692. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155692