The comparison of the basic characteristics of the studied population in terms of energy literacy was divided into three components (knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours) as well as the self-efficacy of the respondents, with the results to be found in

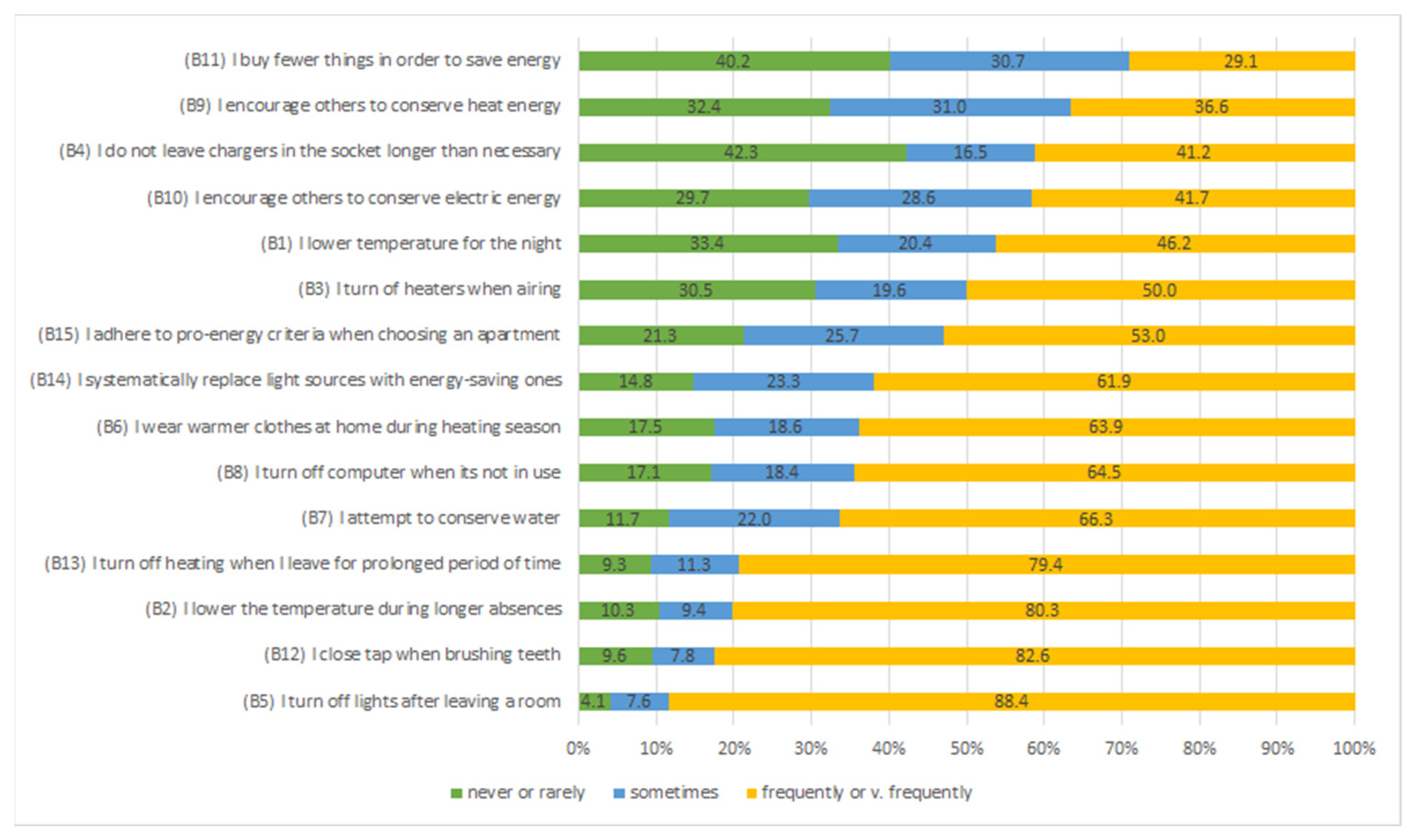

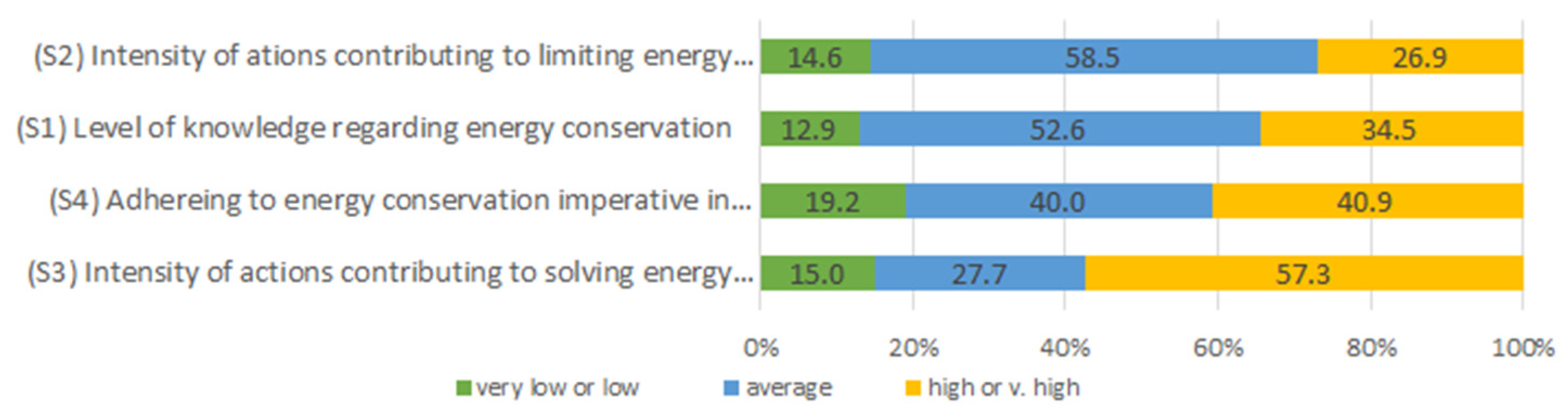

Table 6. The average value in terms of the correct answers in the knowledge component was 2.8 (on a 1–5 scale). The indicators referring to attitudes and behaviours were decisively more positive and reached 3.7 and 3.6 on average, respectively. In terms of self-efficacy, the average value achieved by students was 3.3. These results mean that in the knowledge component respondents indicated 56.4% of the correct answers on average whereas in terms of attitudes, behaviours, and self-efficacy, on average students achieved 73.2%, 72.2%, and 66.2% of the maximum possible score (5).

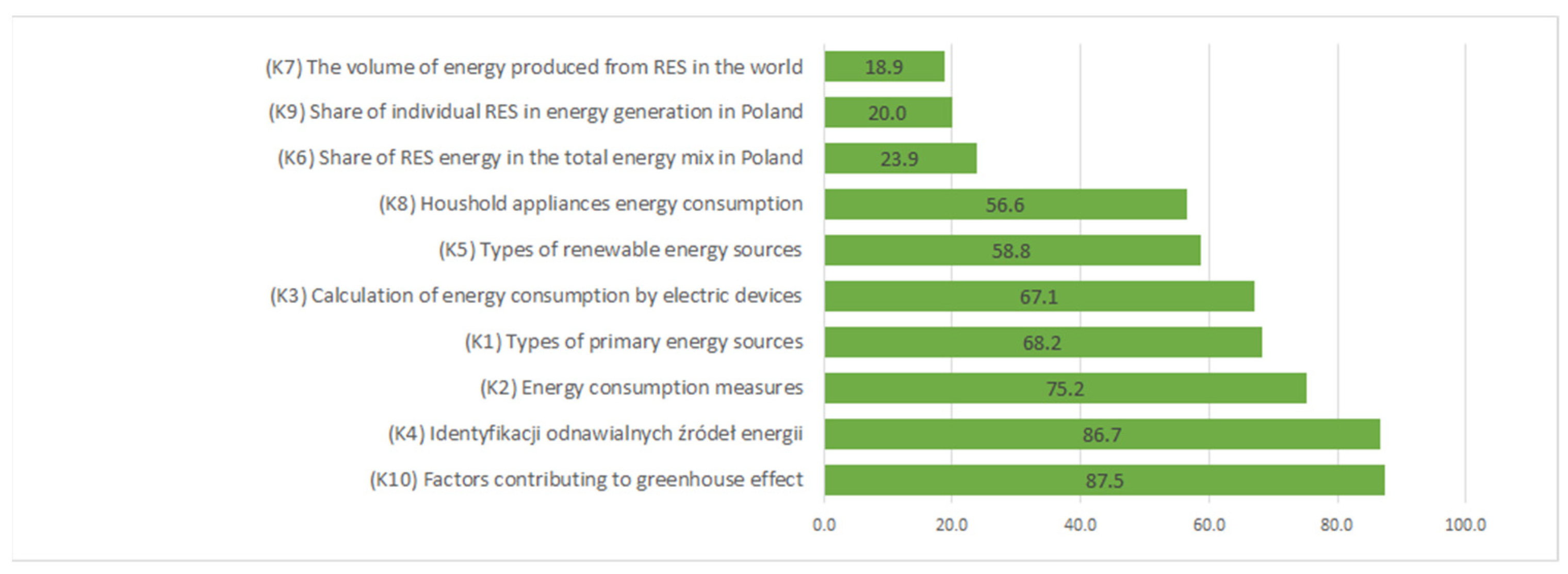

In the knowledge component, the major discrepancy between the average score of the respondents regarding general knowledge (2.8) and the values of the respective indicators for the ecology knowledge subcategory (3.9) and RES knowledge (2.1) is most eye-catching. In the first instance, the difference is 1.1 point in plus, in the second instance it is 0.7 point in minus. In turn in the case of the “attitude” component the respective indicators characterising sub-components, i.e., the attitude towards RES (3.7) and ecology (3.4) approximate or are equal to a rather high value of the indicator calculated for the entirety of this category (3.7). In the “behaviour” component, the subcategory of pro-ecological behaviours achieved the average score of 3.0–0.6 point lower than the average score for the whole category.

4.2. Statistical Analysis

In the further part of the analysis, conducted by way of the Wilcoxon test, we verified to what degree categories such as gender, form of inhabitancy (ownership/tenancy), type of town/city, the fact of moving out from family home for the duration of studies, age, and the fact of experiencing fuel poverty (defined as devoting more than 10% of disposable income to covering energy-related costs) diversify attitudes, behaviours, knowledge, and self-efficacy of students in terms of energy-related issues (

Table 7).

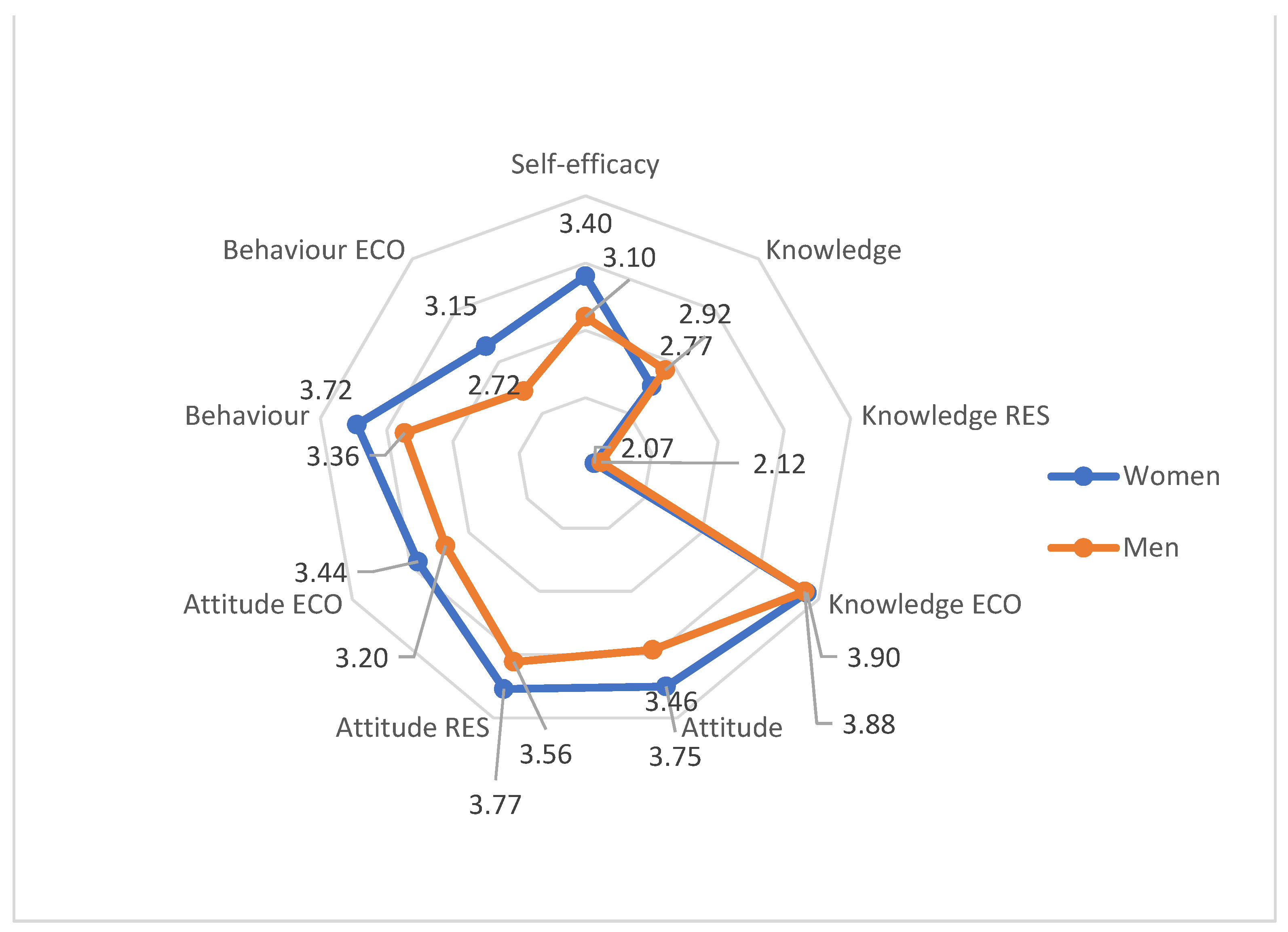

The analysis demonstrated that gender is the category which diversifies in a statistically significant manner the level of knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, and self-efficacy of the surveyed group to the greatest degree in terms of issues related to energy (in all cases with the exception of knowledge related to RES and ecology. Still, these categories demonstrate a rather low p-value below e.g., 0.1). Other significant categories are the fact of moving out from home for the duration of studies and fuel/energy poverty.

Table 8 and

Figure 5 present the results for the three aforementioned categories (gender, moving out from home, and energy poverty), which in a statistically significant manner diversify self-assessment, knowledge, attitude, and behaviours of the respondents. Women display a markedly higher level of pro-environment behaviours (by 0.41 on average on a five-grade scale) as well as the behaviours related to the broadly understood energy conservation (by 0.36 on the aforementioned scale). In comparison to men, women are characterised by a lower value of the synthetic indicator only in the case of knowledge related to energy (by 0.21) and RES knowledge (by 0.16).

The second category which most frequently diversifies the studied population is the fact of moving out from the family home for the duration of studies or remaining therein. Statistically significant differences between these two groups concern the broadly understood attitudes towards energy, attitudes towards RES and ecology, as well as behaviours in terms of respecting energy and behaviours regarding ecology. In nearly all those cases (apart from ecology knowledge) the persons who moved out for the duration of studies are characterised by higher values of synthetic indicators than in the case of people who remained in family homes. The most significant differences are displayed in cases of pro-ecology behaviours (0.17 pt), pro-ecology attitudes (0.14 pt), and the knowledge regarding RES (0.12 pt). Thus, we may present a thesis that the fact of moving out from a family home facilitates development of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours regarding taking responsibility for natural environment.

In terms of the legal form of inhabitancy (ownership or tenancy) the statistically significant differences between these two groups of respondents only concern pro-ecological attitudes i.e., the persons who are living in rented housing achieved the average value of the indicator at the level of 3.41 whereas in the case of people living in a flat/house they own the value of this indicator was lower (3.30 on a five-grade scale). Moreover, in the case of a type of town/city where the respondents reside, the differences between residents of villages and towns/cities were only statistically significant in the case of pro-ecology attitudes (the value of the indicator for residents of towns/cities was 3.42 and 3.30 for residents of villages). The age of the respondents diversifies in a statistically significant manner only in terms of knowledge regarding RES, i.e., the average value of the synthetic indicator in the case of younger persons (up to 22 years of age) is slightly higher (by 0.17 pt) than in the case of older persons (22 years and older).

Whether respondents experienced energy poverty diversifies their level of self-efficacy, attitudes (with the exception of the attitudes towards RES), and behaviours related to energy conservation in a statistically significant manner. Persons experiencing energy poverty display slightly higher: self-efficacy (by 0.12 pt), value of the indicator characterising attitude towards energy conservation (by 0.1 pt), attitude towards RES (by 0.12 pt), and behaviours related to ecology (by 0.14 pt). Thus, financial limitations are tied to higher energy literacy and behaviours related to the conservation of energy.

Table 9 presents an analysis of the inter-dependencies between the adopted characteristics i.e., self-efficacy, knowledge, and attitude towards energy (with division into RES and ecology knowledge) as well as behaviours related to energy conservation (including pro-ecology behaviours). The weakest correlations can be observed between the “knowledge” group and the remaining indicators. It may be ascertained that the level of knowledge does not meaningfully influence attitudes (correlation and dependence coefficient of 0.13) or behaviours (0.01). Within the knowledge category there are also no significant or meaningful correlations between the knowledge concerning RES and knowledge on the subject of ecology (0.08). However, the relationship between self-efficacy and attitudes (0.55) and behaviours (0.66) regarding energy conservation can be observed. In the case of the “attitude” category, a moderate correlation between attitudes towards RES and ecology (0.48) can be observed. We can also observe a dependency between pro-ecology attitudes and attitudes towards RES (0.48).

Finally, on the basis of multivariate linear regression, we can analysed what influence knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy may have on students’ energy conservation behaviours. Since our analysis conducted so far indicates the potential importance of respondent characteristics (age, gender, ownership etc.), we also include them as control variables. Our regression model is

where y is the response (dependent) variable ( indicator), vector

contains k = 14 regressors (based on the constructed indicators, the names are listed in

Table 10, column 2),

is the vector of k + 1 unknown parameters (so that

is the intercept, which corresponds to “1” in vector x), and t is the observation index (t = 1,…, 913).

Table 10 presents the results. Self-efficacy is the most important factor influencing student behaviour: increasing the student’s self-assessment by one unit increases the behavioural response to energy conservation by 0.493. This is followed by attitude, as well as the pro-ecologic components of both knowledge and attitude. When a student’s attitude and the pro-ecological component of his/her attitude are both increased by one unit, his/her positive behavioural response to energy conservation increases by 0.143 and 0.112, respectively. The behavioural response increases by 0.034 for every unit increase in pro-ecologic knowledge. Though this effect is small in comparison to self-efficacy or attitude, it is statistically significant (

p-value = 0.009). More importantly, these findings confirm that there is no statistically significant impact of general knowledge on energy conservation behaviour, and that gender is a statistically significant factor in it. In terms of energy conservation behaviour, a female student’s energy literacy is 0.146 units higher than that of a male student. Furthermore, the findings for energy poverty show that increasing the poverty indicator by one unit increases energy conservation behaviour by 0.046. The

p-value for the “poverty” parameter (

) is 0.119, which is not far removed from the usual 0.1 significance threshold. Hence, given our previous findings in this regard, it seems that, though more uncertain, the impact of energy poverty is also a factor.