The Influence of Environmental Awareness on Responsible Energy Consumption—The Case of Households in Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

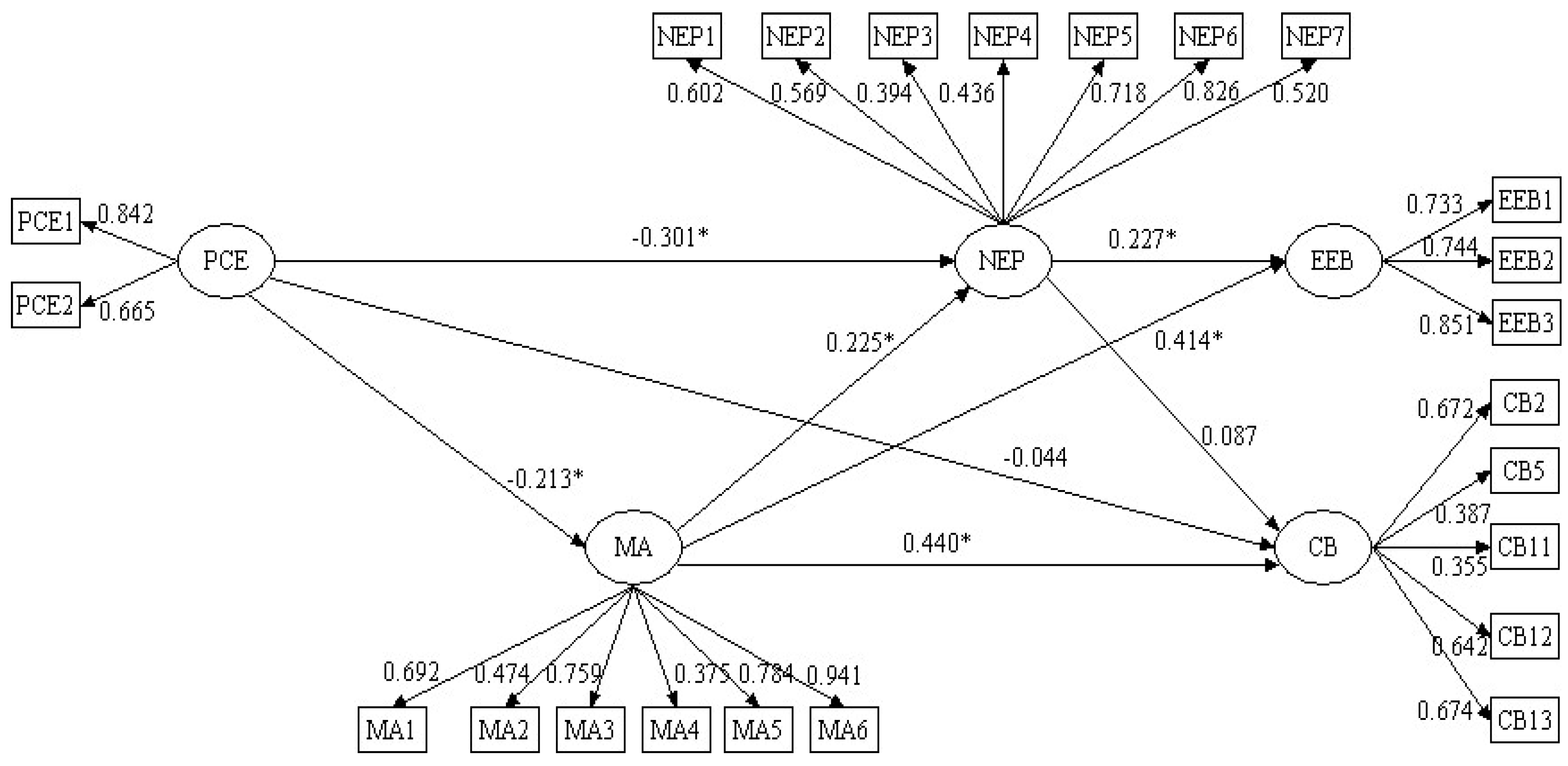

- To what extent does environmental awareness (NEP) influence the two dimensions of responsible energy consumption—curtailment behavior (CB) and energy efficiency behavior (EEB)?

- Does the perceived stringency of environmental regulations (PSER) moderate the impact of environmental awareness on responsible energy consumption and to what extent?

- How does perceived consumer efficiency (PCE) affect environmental awareness (NEP) and sensitivity mobilization (MA)?

- How can sensitivity mobilization (MA) influence the environmental awareness (NEP) of households and responsible energy consumption (CB and EEB)?

2.2. Questionnaire Development

2.3. Data Collections

2.4. Sample

3. Results

3.1. Scales’ Dimensionality

3.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

3.3. SEM Model Parameters and Goodness-of Fit

3.4. Effects of Mediation and Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gornall, J.; Betts, R.; Burke, E.; Clark, R.; Camp, J.; Willett, K.; Wiltshire, A. Implications of climate change for agricultural productivity in the early twenty-first century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 2973–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihiko, M.K.; Kinoti, M.W. The business case for climate change: The impact of climate change on Kenya’s public listed companies. In Climate Change and the 2030 Corporate Agenda for Sustainable Development. Advances in Sustainability and Environmental Justice; Gonzalez-Perez, M.A., Leonard, L., Eds.; Emerald: London, UK, 2017; Volume 19, p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, M. Capitalism and climate change. In Theoretical Discussion, Historical Development and Policy Responses; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Renewable and Non-Renewable Resources. Available online: https://www.conserve-energy-future.com/renewable-and-nonrenewable-resources.php (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Carrete, L.; Castano, R.; Felix, R.; Centeno, E.; Gonzalez, E. Green consumer behavior in an emerging economy: Confusion, credibility, and compatibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M. Sustainable Marketing; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carvill, M.; Butler, G.; Evans, G. Sustainable Marketing. How to Drive Profits with Purpose; Bloomsbury Business: Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.R.; Kaur, T.; Syan, A.S. Sustainability Marketing–The Environmental Perspective; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fisk, G. Criteria for a theory of responsible consumption. J. Mark. 1973, 37, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, R. Naturaleza y funciones de las actitudes ambientales. Estud. Psicol. 2001, 22, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Gupta, S. Consuming responsibly: Exploring Environmentally responsible consumption behaviors. J. Glob. Mark. 2018, 31, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.R.; Kaur, T.; Syan, A.S. Sustainability Marketing. New Directions and Practices; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; She, Q. Developing a Trichotomy Model to Measure Socially Responsible Behaviour in China. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 53, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, J.; Marell, A.; Nordlund, A. Green consumer behavior: Determinants of curtailment and eco-innovation adoption. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L.; Guagnano, G.A. Values, Beliefs and Proenvironmental Action: Attitude Formation toward Emergent Attitude Objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 1611–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.; Wildavsky, A. Risk and Culture; University of California Press: Berkeley, UK; Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. A refutation of environmental ethics. Environ. Ethics 1990, 12, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culiberg, B.; Rojšek, I. Understanding environmental consciousness: A multidimensional perspective. Vrijednost Potros. Din. Okruz. 2008, 131–145. Available online: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/441713910 (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “new environmental paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Wolff, G.; Daily, G.C.; Hughes, J.B.; Daily, S.; Dalton, M.; Goulder, L. Knowledge and The Environment. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 30, 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, D.; Bultena, G.; Hoiberg, E.; Nowak, P. Measuring Environmental Concern: The New Environmental Paradigm Scale. J. Environ. Educ. 1982, 13, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaLonde, R.; Jackson, E.L. The New Environmental Paradigm Scale: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness? J. Environ. Educ. 2022, 33, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A. Environmental aesthetics. In The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, 2nd ed.; Gaut, B., Lopes, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar]

- Antil, J.H. Socially Responsible Consumers: Profile and Implications for Public Policy. J. Macromark. 1984, 4, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, F.E., Jr. Determining the Characteristics of the Socially Conscious Consumer. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardes, E.W.; Espanhol, C.A.; Cruz, P.B.D. Green consumption: Consumer behavior after an environmental tragedy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2001, 64, 1156–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.T.; Dillon, W. On Receptivity to Information Furnished by the Public Policymaker: The Case of Energy. In Educators’ Conference Proceedings; Beckwith, N., Houston, M., Mittelstaedt, R., Monroe, K.B., Ward, S., Eds.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1979; pp. 550–556. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.T. Self-Perception Based Strategies for Stimulating Energy Conservation. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 8, 381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Garg, P.; Singh, S. Pro-environmental purchase intention towards eco-friendly apparel: Augmenting the theory of planned behavior with perceived consumer effectiveness and environmental concern. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.J.; Seligman, C.; Fazio, R.H.; Darley, J.M. Relating Attitudes to Residential Energy Use. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarimoglu, E.; Binboga, G. Understanding sustainable consumption in an emerging country: The antecedents and consequences of the ecologically conscious consumer behavior model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Paul, J.; Sharma, R. The moderating influence of environmental consciousness and recycling intentions on green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Muralidharan, S. What triggers young Millennials to purchase eco-friendly products? The interrelationships among knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness, and environmental concern. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Examining antecedents of consumers’ pro-environmental behaviours: TPB extended with materialism and innovativeness. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, B.; Schivinski, B. Individualism/collectivism and perceived consumer effectiveness: The moderating role of global–local identities in a post-transitional European economy. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomberg, E.; McEwen, N. Mobilizing community energy. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippman, S.A.; Neilands, T.B.; Leslie, H.H.; Maman, S.; MacPhail, C.; Twine, R.; Peacock, D.; Kahn, K.; Pettifor, A. Development, validation, and performance of a scale to measure community mobilization. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 157, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macias, T.; Williams, K. Know Your Neighbors, Save The Planet: Social Capital and the Widening Wedge of Pro-Environmental Outcomes. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 391–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiadat, Y.; Kelly, A.; Roche, F.; Eyadat, H. Green and competitive? An empirical test of the mediating role of environmental innovation strategy. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, T.S.; Overland, I.; Vakulchuk, R. Environmental performance of foreign firms: Chinese and Japanese firms in Myanmar. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P. Environmental awareness and initiatives in the Swedish and Polish hotel industries—Survey results. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 662–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K. Environmental awareness, governance and public participation: Public perception perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 67, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. Consumers’ susceptibility to interpersonal influence as a determining factor of ecologically conscious behavior. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainieri, T.; Barnett, E.G.; Valdero, T.R.; Unipan, J.B.; Oskamp, S. Green buying: The influence of environmental concern of consumer behaviour. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 137, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, L.T.; Simpson, E.T. The determinants of consumers’ purchase decisions for recycled products: An application of acquisition-transition utility theory. In Advances in Consumer Research; Kardes, F.R., Sujan, M., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1995; Volume 22, pp. 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Gatersleben, B.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Measurement and Determinants of Environmentally Significant Consumer Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, C.; Krystallis, A. Purchasing motives and profile of Greek organic consumer: A countrywide survey. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 730–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Final Energy Consumption in Households Per Capita, Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_07_20/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PKEE Polski Komitet Energii Elektrycznej. Available online: https://pkee.pl/aktualnosci/dziewieciu-na-dziesieciu-polakow-deklaruje-ze-oszczedza-energie-elektryczna/ (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Ellen, P.S.; Wiener, J.L.; Cobb-Walgren, C. The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.L. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1965, 30, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beran, R.; Srivastava, M.S. Bootstrap Tests and Confidence Regions for Functions of a Covariance Matrix. Ann. Stat. 1985, 13, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Composite-Based Structural Equation Modeling: Analyzing Latent and Emergent Variables; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschafer, J.; Morrison, M.; Oczkowski, E. The relative importance of household norms for energy efficient behavior. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measuring Scale Items |

|---|

| Environmental Awareness Scale (NEP) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Curtailment Behavior Scale (CB) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Energy Efficiency Behavior Scale (EEB) |

|

|

|

| Sensitivity Mobilization (Mobilizing Attitude) Scale (MA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perceived Stringency Scale (PSER) |

|

|

| Perceived Consumer Effectiveness Scale (PCE) |

|

|

| Characteristics | Item | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 43.0 |

| Male | 57.0 | |

| Age (years) | 18–24 | 24.9 |

| 25–34 | 11.8 | |

| 35–44 | 22.3 | |

| 45–54 | 25.9 | |

| 55–64 | 9.7 | |

| 65 and more | 5.3 | |

| Education | Primary | 2.2 |

| Vocational | 6.4 | |

| Secondary | 36.1 | |

| Higher | 54.9 | |

| Number of householdmembers | 1 person | 9.6 |

| 2 persons | 25.6 | |

| 3 persons | 22.3 | |

| 4 persons | 27.4 | |

| 5 persons | 10.2 | |

| 6 persons and more | 4.8 | |

| Place of residence | Rural areas | 24.8 |

| Towns, up to 100,000 residents | 26.7 | |

| Towns, 101,000–500,000 residents | 31.6 | |

| Towns, over 501,000 residents | 16.9 | |

| Self-assessment of the material situation | Very bad | 1.1 |

| Bad | 3.6 | |

| Sufficient | 28.8 | |

| Good | 53.2 | |

| Very good | 13.4 |

| Measure | NEP | MA | EEB | PCE | CB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach′s Alpha | 0.742 | 0.852 | 0.751 | 0.718 | 0.457 |

| McDonald′s Omega | 0.739 | 0.841 | 0.751 | 0.732 | 0.471 |

| Dijkstra-Henseler′s rho | 0.767 | 0.883 | 0.751 | 0.756 | 0.500 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.331 | 0.504 | 0.602 | 0.582 | 0.160 |

| Convergent validity | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Discriminant validity | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| NEP | MA | EEB | PCE | CB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEP | 1.00 | ||||

| MA | 0.258 | 1.00 | |||

| EEB | 0.354 | 0.402 | 1.00 | ||

| PCE | 0.360 | 0.211 | 0.163 | 1.00 | |

| CB | 0.373 | 0.650 | 0.770 | 0.270 | 1.00 |

| Paths | Estimate | 95% C.I. | Parameter Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEP – CB | 0.099 | −0.025; 0.216 | 0.003 |

| NEP – EEB | 0.246 * | 0.139; 0.347 | 0.003 |

| PSER – CB | −0.075 | −0.158; 0.004 | 0.001 |

| PSER – EEB | 0.042 | −0.044; 0.126 | 0.001 |

| PSER × NEP – CB | −0.015 | −0.078; 0.043 | 0.002 |

| PSER × NEP – EEB | 0.051 | −0.017; 0.126 | −0.003 |

| Hypothesis | Decision |

|---|---|

| H1: The greater the environmental awareness, the greater the tendency to curtailment behavior | 0.087 p > 0.05 not accepted |

| H2: The greater the environmental awareness, the greater the tendency to energy efficiency behavior | 0.227 p < 0.05 accepted |

| H3: The lower the level of perceived consumer (in)efficiency, the higher the level of environmental awareness. | −0.301 p < 0.05 accepted |

| H4: The lower the level of perceived (in)efficiency, the higher the level of mobilization. | −0.213 p < 0.05 accepted |

| H5: The higher the mobilization level, the greater the tendency to curtailment behavior. | 0.414 p < 0.05 accepted |

| H6: The higher the mobilization level, the greater the tendency to energy efficiency behavior. | 0.440 p < 0.05 accepted |

| H7: The higher the mobilization level, the greater the environmental awareness. | 0.225 p < 0.05 accepted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaciow, M.; Rudawska, E.; Sagan, A.; Tkaczyk, J.; Wolny, R. The Influence of Environmental Awareness on Responsible Energy Consumption—The Case of Households in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 5339. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155339

Jaciow M, Rudawska E, Sagan A, Tkaczyk J, Wolny R. The Influence of Environmental Awareness on Responsible Energy Consumption—The Case of Households in Poland. Energies. 2022; 15(15):5339. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155339

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaciow, Magdalena, Edyta Rudawska, Adam Sagan, Jolanta Tkaczyk, and Robert Wolny. 2022. "The Influence of Environmental Awareness on Responsible Energy Consumption—The Case of Households in Poland" Energies 15, no. 15: 5339. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155339

APA StyleJaciow, M., Rudawska, E., Sagan, A., Tkaczyk, J., & Wolny, R. (2022). The Influence of Environmental Awareness on Responsible Energy Consumption—The Case of Households in Poland. Energies, 15(15), 5339. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155339