Abstract

The plastic bottles that are used for packaging water are harmful to the environment. The objective of this study was to examine the influence of consumers’ environmental concern on both their intention to reduce consumption of water sold in single-use plastic bottles and their actual behaviour. An extended version of the theory of planned behaviour is used as the main theoretical framework. Structural equation modelling is employed based on data gathered in 2020 from 1011 Polish respondents to test the study’s hypotheses. The results support the model, as all tested relations are statistically significant. More specifically, we confirm the indirect impact of environmental concern on both intention and behaviour concerning bottled water consumption (BWC): environmental concern is positively related to attitudes towards reducing BWC, subjective norms regarding reduction in BWC, perceived behavioural control over BWC, and perceived moral obligation to protect natural resources, all of which, in turn, are positively related to intention to reduce BWC. We also prove that intention to reduce BWC is positively related to consumption of non-bottled water. The results may serve to guide decision makers seeking to promote ecologically friendly behaviour.

1. Introduction

Water makes up 60% of the human body (up to 75% in the case of children). The Institute of Medicine of the National Academies recommends that women ingest 91 ounces (2.7 L) and men ingest 125 ounces (3.7 L) of water per day through both beverages and food [1]. Given that hydration is vital, a huge number of people all over the world, in both developed and developing countries, consume bottled water. Studies show that although it is healthy to drink water, bottled water has no benefit relative to tap water [2]. Despite this, people drink a lot of bottled water (over USD 200 billion worth per year, globally). According to Statista Report [3], consumption of bottled water per capita in 2018 was the highest in Mexico and Thailand at 72.4 gallons (over 274 L). What is more, worldwide consumption has been increasing. According to a report by The Business Research Company [4], from 2014 to 2017, the global bottled water market grew by 9% annually, and it is expected to continue to grow.

Most bottled water is packaged in plastic bottles, and only a fraction of the bottles (47% globally) are collected and recycled, while approximately six hundred billion plastic bottles are thrown out every year worldwide [5]. Of the 78 million metric tons of plastic packaging produced globally each year, only 14% is recycled, while nine million tons ends up in the oceans [6]. Bottled water consumption (BWC), thus, greatly harms the environment [7]. It is vital, then, to reduce usage of plastic packaging, including plastic bottles. Previous studies tested numerous variables’ influence on intention to behave in a more environmentally friendly manner [8,9]. Environmental concern was found to have a significant influence [10,11].

Previous studies on the influence of environmental concern on environmentally responsible behaviour may be divided into two groups. The first examines the direct influence [12,13,14]. The other one researches the indirect impact [10,15,16]. In many of these studies, the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is used as a theoretical framework [15,17,18,19]. Given that intentions are the focal point of TPB and our objective is to examine the influence of environmental concern on intention to reduce consumption of single-use bottled water, we use the same theoretical framework. Intentions are derived from attitudes, both from the perspective of the individual and from the perceived perspective of “the others” meaningful for an individual (whose opinions are important to one), which is manifested in subjective injunctive norm. TPB is derived from the theory of reasoned action but includes an additional variable: perceived behavioural control, which captures individuals’ range of control for a given behaviour [20]. We test the extended TPB, which has been used to examine intention to behave in an environmentally friendly way [21]. This means that we take into account personal norms, which embody individuals’ sense of moral responsibility for their choices. Consumption of water packaged in single-use plastic bottles may present moral dilemmas concerning the harm that the waste does to the environment.

In this study, we aim to understand how environmental concern influences consumers’ intention to reduce consumption of single-use bottled water and to consume non-bottled water. Our objective is also to understand how intention to reduce consumption of single-use bottled water influences consumption of non-bottled water.

This study develops a model explaining individuals’ decision-making concerning their consumption of water sold in plastic bottles. The model focuses on both intentions and behaviour by integrating the variables established in TPB (attitude towards the behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control) with perceived moral obligation into one theoretical framework.

First, we present the concept of environmental concern as a determinant of consumption intentions and behaviours. Then, we present the relation between environmental concern and BWC. Next, we develop our hypotheses, present our method of obtaining the data (gathered from 1011 Polish respondents in February and March 2020), and present our results. Finally, we discuss the results, form conclusions, and present the limitations of the current study and opportunities for future research.

1.1. Environmental Concern as a Determinant of Consumer Intentions and Behaviours

Overconsumption and wasteful resource disposal pose a serious threat to humankind. Efforts to permanently change people’s environmentally destructive behaviour, thus far, have not been fully successful. For this reason, it is extremely important to understand the mechanism of the pro-environmental behaviour of individuals. Environmental concern is expressed both in people’s attitudes and in their behaviour towards the environment [22]. It characterises a person’s environmental worries, compassion, likes, and dislikes [14,23]. It has also been defined as an attitude towards facts and one’s own behaviour or others’ behaviour with consequences for the environment [24]. People use this term to refer to the whole range of environmentally related perceptions, emotions, knowledge, attitudes, values, and behaviours [15].

It has been a widely discussed and researched topic for about fifty years [13,25,26]. Although research on environmental concern as a determinant of consumer purchasing behaviour started in the early 1970s [27], it remains unclear how to explain the emergence of environmental concern and its influence on consumer behaviour. There are two main concepts in this regard: postmaterialist values theory and the objective problems explanation [28]. The postmaterialist values theory was formulated by Inglehart (1995), who claimed that when basic needs are satisfied, people begin to take an interest in non-essential needs connected with quality of life; the theory directly refers to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [29]. Inglehart’s claim was supported by subsequent research [29] using European Union data that proved that the postmaterialist and wealthiest countries had the most personal behaviour directed at mitigating climate change (such behaviour is assumed to be a consequence, whether direct or indirect, of environmental concern). On the other hand, in some of the most affluent societies where consumption increased rapidly (North America, for example), materialism is negatively related to environmental concern [30].

The other explanation for the emergence of environment concern—the objective problems explanation—is related to experience with environmental disasters. The disaster of the nuclear plant in Fukushima caused an increase in environmental concern in Germany, especially among people living close to nuclear reactors [31]. It seems that the objective problems explanation cannot be applied to every country, but it may be that individuals affected by natural disasters will become more environmentally concerned in societies with postmaterialist values [28].

The other important stream of research is related to the consequences of growing environmental concern on consumer intentions and behaviour. This area of research was connected with a wide range of environmentally friendly aspects of consumption, or even green consumption in general [11,32,33,34]. Such aspects include specific products, services, and practices, such as energy use and saving [35], energy-efficient appliances [9,10], biofuels [36], means of transportation (including the purchase of environmentally friendly vehicles), and green hotels [21]. These studies confirm the influence of environmental concern on consumers’ intentions to choose eco-friendly products and solutions. However, it has also been found that people more frequently declare such intentions than they behave in line with their declared intentions [37], which means that the reasons for environmental concern differ from the reasons for environmentally friendly behaviour. This has been found on the personal level [12,23,29,32,38], in both psychographic (knowledge, attitudes, values, type of motivation, past behaviour) and socio-demographic (gender, age, education, political preferences) attributes. It has also been proven that national culture may affect environmental concern and behaviour [39].

1.2. The Relation between Environmental Concern and Bottled Water Consumption

Research into the motives behind the purchasing of bottled water is relatively sparse [40]. Ward, Cain, and Mullally (2009) found convenience, cost, and taste to be the primary motives and health beliefs to be insignificant motives. The participants in their study believed that bottled water had a detrimental effect on the environment. Another study [41] similarly found that consumers buy bottled water mainly for organoleptic reasons related to taste, smell, and sight and because of concerns about poor water quality and its impact on human health. The same study found that other determinants of the purchase of bottled water include convenience and lifestyle.

Van der Linden (2013) found that consumption of bottled water decreases as awareness of environmental damage increases. The results also show that beliefs about health, taste, water quality, lifestyle, environment, and perceived alternatives correlate with the consumption of bottled water and that the strength of the beliefs varies greatly depending on the style of consumption [42]. Ballantine, Ozanne, and Bayfield also studied the motives for purchasing bottled water and consumer perceptions about the potential environmental effects of the packaging [43]. They found the main determinants of the purchasing decisions to be health (including personal health and hygiene) and functionality (convenience, taste, and self-image). In the study, the respondents perceived bottled water as healthy, hygienic, attractively packaged, convenient, and excellent-tasting. They also showed that the respondents were aware of the environmental harmfulness of the packaging.

The importance of the problem related to the harmful impact of plastic bottles on the environment was confirmed by research on the possibility of using biodegradable bottles instead of plastic ones. Orset, Barret, and Lemaire found that 62.8% of respondents were convinced that plastic bottles are harmful for the environment and 88.5% valued recyclable packaging [44].

1.3. Development of Hypotheses

In this study, environmental concern is defined as a belief in the importance of environmental issues for human beings. As mentioned above, many previous studies have proven that the impact of environmental concern on eco-friendly behaviour is moderated by the variables considered in TPB: attitude towards the behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control [11,15,21,45,46]. We apply TPB but include, as an additional variable, personal norms—specifically, perceived obligation to act ethically by treasuring natural resources. Including the additional variable may enhance our understanding of the theoretical mechanism and increase the theory’s power to predict intention and behaviour [20,47].

Attitude in the TPB model is defined as the degree to which an individual has a favourable or unfavourable assessment of the behaviour in question. A more positive attitude generates a more positive behavioural intention and vice versa [20]. In this study, attitude is defined as the evaluation that arises when an individual reduces BWC. Previous studies found that environmental concern influences attitudes towards eco-friendly purchasing behaviour in general [13] and in regard to particular goods and services, such as environmentally friendly cars [48], energy-efficient appliances [10], and green hotels [21]. We thus formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Environmental concern (EC) is positively related to attitude (AT) to reducing BWC.

Subjective injunctive norms are the perceived opinions of others who are close or important to a person and who influence their behaviour. They also refer to feelings of social pressure [20]. According to previous studies, environmental concern is positively related to subjective norms concerning eco-friendly behaviour, but the strength of the relation varies. Albayrak et al. (2013), for example, found the impact of environmental concern on subjective norms to be stronger compared with the influence of EC on other TPB variables [13], while Chen and Tung [21] found the effect to be weaker in their research on intention to stay at green hotels. Considering the existence and strength of that relation, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Environmental concern (EC) is positively related to subjective norms (SN) concerning reduction in BWC.

Perceived behavioural control refers to a person’s perception of the possible difficulties and obstacles when engaging in a certain behaviour. It expresses the feeling of control an individual has with respect to that behaviour. The more a person is capable of controlling the opportunities and resources relevant to a behaviour, the more likely they will be to engage in the behaviour [20]. Previous research found that environmental concern is positively related to perceived behavioural control on environmental issues [21]. In the current study, perceived behavioural control refers to perceived control over the amount of bottled water an individual drinks. We formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Environmental concern (EC) is positively related to perceived behavioural control (PBC) over BWC.

We added perceived moral obligation to the TPB model, as it has been proven that consumer choices that influence the environment are related to values that transcend self-interest [23,35]. A value is defined as a belief regarding desirable end states or modes of action that transcends specific situations, guides selection or evaluation of behaviour, people, and events, and is ordered by importance relative to other values to form a system of value priorities [49]. Two motivational types of values—universalism and benevolence—are more group-oriented than individually oriented and refer to altruistic behaviour, which is positively related to pro-environment action [50]. Perceived moral obligation was included in another study concerning eco-friendly behaviour [21]. Perceived moral obligation means that an individual feels responsible for behaving morally when a situation calls for a choice. It has been found that in comparison with other TPB variables, environmental concern has the greatest positive effect on perceived moral obligation [21], so we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Environmental concern (EC) is positively related to perceived moral obligation (PMO) to reduce BWC.

The results concerning the influence of an eco-friendly attitude on eco-friendly behaviour are inconsistent. Valle et al. [51] find that the relation between recycling attitude and recycling participation is slightly negative. However, in many other studies, that relation was found to be positive. For example, de Leeuw et al. [52] find that attitude on eco-friendly behaviour has a small but positive effect on intention to behave in an eco-friendly manner. Similar results were obtained in the research concerning intention to revisit green hotels [53]; however, another study concerning the same service [54] found that attitude is a strong predictor of intention. In research concerning green information technology (IT), of all the TPB variables, attitude on green IT was proven to have the strongest influence on the intention to use green IT [45]. Similar results were obtained in a study on intention to choose organic items on menus [55] and on intention to consume organic food in general [56]; the relation between attitude and intention was found to be stronger than relations between other TPB variables and intention. As the majority of the studies confirm the TPB model’s posited relation between attitude and intention, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Attitude on reducing BWC (AT) is positively related to intention to reduce (IR) BWC.

According to TPB, subjective norms may influence behavioural intentions positively [52,53,57], encouraging a person to behave in a given way, or they may be negatively related to intention to engage in eco-friendly behaviour [10,58], meaning that they prevent an individual from having an intention to behave in an eco-friendly manner. However, the majority of previous studies found that subjective norms are positively related to eco-friendly behaviour, so we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Subjective norms (SN) concerning reduction in BWC are positively related to intention to reduce (IR) BWC.

In previous studies concerning the impact of perceived behaviour control on eco-friendly behaviour, the results are highly inconsistent. Al-Swidi et al. (2014) find that perceived behavioural control is not related to intention to buy organic food [59]. Similar results are found in the research concerning intention to buy hybrid cars [60] and green sportswear [61], whereas de Leeuw et al. [52] and Prendergast and Tsang [62] found that of all TPB variables, perceived behavioural control is the strongest predictor of intention to engage in pro-environment behaviour. In the current study, we posit, in line with TPB, that the more people feel they have control over the amount of bottled water they drink, the more they are willing to reduce BWC:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Perceived behavioural control (PBC) over BWC is positively related to intention to reduce (IR) BWC.

In the current study, perceived moral obligation is connected with responsibility for preservation of natural resources. Given that the vast majority of bottled water in the country where the survey was conducted (Poland) is sold in plastic bottles, consumption of bottled water may be potentially hazardous to the environment. We posit, as do previous studies [21,37,63], a positive effect of perceived moral obligation on intention to reduce BWC:

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Perceived moral obligation (PMO) connected with BWC is positively related to intention to reduce (IR) BWC.

As said before, according to TPB, intention predicts behaviour. The theory may be applied to explain eco-friendly behaviour [52]. However, much research shows the existence of an attitude–behaviour gap in this regard [19,37]. The final hypothesis in this study concerns the influence of intention to reduce BWC on self-reported consumption of non-bottled water:

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Intention to reduce (IR) BWC is positively related to non-bottled water consumption behaviour (NBWCB).

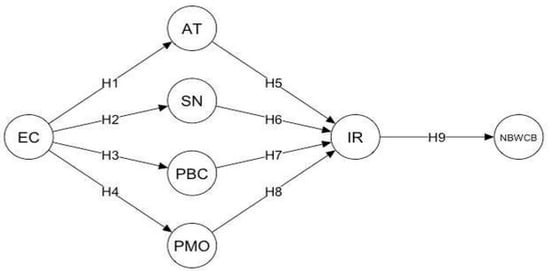

All hypotheses developed in the research are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model. EC—Environmental concern; AT—Attitude on reducing bottled water consumption; SN—Subjective norms concerning reduction of bottled water consumption; PBC—Perceived behavioural control over bottled water consumption; PMO—Perceived moral obligation to reduce bottled water consumption; IR—Intention to reduce bottled water consumption; NBWCB—Non-bottled water consumption behaviour.

2. Materials and Methods

The hypotheses were tested using data collected from 1011 respondents. The survey took place in February and March 2020 in Poland, where almost all bottled water is sold in plastic bottles and only about 20% of the bottles are recycled [64]. The data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire with Computer-Assisted Web Interview. The first part of the questionnaire comprised questions about seven variables: environmental concern (EC), attitude towards positive impact of reduction in single-use BWC on the environment (AT), subjective injunctive norms (SN), perceived behavioural control (PBC), perceived moral obligation (PMO), intention to reduce BWC (IR), and non-bottled water consumption behaviour (NBWCB). Participants referred to all 21 statements on a seven-point scale (ranging from 1, “I strongly disagree”, to 7, “I strongly agree”). The complete list of questions and sources is presented in supplementary Table A1 (Appendix A). The second part of the questionnaire consisted of questions about the respondents’ personal information.

The participants in the study included 1011 respondents, and their average age was 24.5 years (SD = 8.35, min = 16, max = 67). The sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents (N = 1011).

The study was conducted in two stages, as proposed by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), to separately analyse the validity and reliability of the constructs and to test the hypotheses based on the adopted research model by using structural equation modelling (SEM). We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis first to test for the quality and adequacy of the measurement [65] in an attempt to ensure the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the studied constructs. Secondly, in order to understand the causal relations among the latent variables and to test our hypotheses, we employed SEM [66]. The R programming environment and lavaan package were used. All analyses were performed with the use of bootstrapping to improve the reliability of the results.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model

The overall goodness-of-fit indices of the measurement model are as follows: chi-square/degree of freedom (596.633/167) = 3.57, GFI = 0.985, AGFI = 0.978, CFI = 0.978, RMSEA = 0.05, and TLI = 0.972. These indices show data correctness, indicating model fitness. All statistics met the standards of model fitness. As a next step, all variables were tested for both convergent validity and discriminant validity. In order to examine convergent validity, we employed both measures of composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values. According to Fornell and Larcker [67], AVE values greater than 0.5 imply convergent validity of the studied constructs. Likewise, the value of the CR for all variables must be above 0.60 ([68], p. 160). In Table 2, all values of AVE and CR (and Cronbach’s α) are presented as well as mean and standard deviation values for each statement (broken down into women and men). The results show that all AVE values are greater than 0.5 and all CR values are greater than 0.6 (and Cronbach’s α is greater than 0.7). Therefore, the latent variables of this study achieve convergent validity. All variable loadings for the tested items were found to be significant at p = 0.001.

Table 2.

Constructs, reliability, and convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was tested by comparing the AVE values with squared multiple correlations (see Table 3). The results revealed that the constructs had a significantly higher square root of AVE values than their correlations with other constructs. This indicates discriminant validity for each construct [67]. That, in turn, means that the two constructs can be viewed as distinct yet correlated variables. Hence, the constructs and measurement model items were deemed appropriate for testing our hypotheses and structural models.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

3.2. Structural Model and Testing of Hypotheses

We employed SEM analysis to estimate the path coefficients of the relations between the constructs in the research model. The following indices were utilised to evaluate the fit of the model: chi-square/degree of freedom (697.655/178) = 3.92, GFI = 0.982, AGFI = 0.975, CFI = 0.974, RMSEA = 0.054, and TLI = 0.969. All of these indices and the estimations showed model fitness [69]. The model explains 62% (R2 = 0.62) of the variance for IR and 43% (R2 = 0.43) of the variance for NBWCB. Thus, both R² values indicate that the model explains a substantial amount of variance.

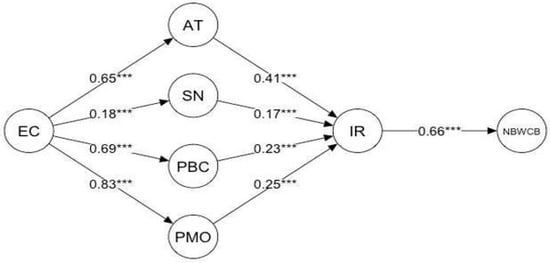

We tested the hypotheses using the bootstrapping method (n = 5000). The results of the SEM reveal that the path coefficients running from environmental concern to attitude towards reducing BWC, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and perceived moral obligation are all statistically significant (H1: β = 0.65, p < 0.001; H2: β = 0.18, p < 0.001; H3: β = 0.69, p < 0.001; H4: β = 0.83, p < 0.001) and in the expected directions. In other words, all of the above variables are influenced by environmental concern. The results also indicate that intention to reduce BWC is determined by attitude towards reducing BWC, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and perceived moral obligation. All four of these determinants turned out to be statistically significant (H5: β = 0.41, p < 0.001; H6: β = 0.17, p < 0.001; H7: β = 0.23, p < 0.001; H8: β = 0.25, p < 0.01) and in the expected directions. The results also revealed a positive, significant relation between intention to reduce BWC and non-bottled water consumption behaviour (H9: β = 0.66, p < 0.001). To sum up, all of the hypotheses in the research framework are supported (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of structural equation modelling (SEM).

The results of hypotheses testing are also presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Results of hypotheses testing. Note: *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

A vast body of literature explores individuals’ motivations with respect to BWC. Most of it focuses on motivations of health, convenience, taste, and habit [42,70,71,72,73,74]. According to one point of view, water packaged in single-use bottles is perceived as safer for health than, for instance, tap water [75]. Paradoxically, health concern is a main factor that stops consumers from purchasing bottled water because single-use plastic bottles pose a threat to individuals’ health [76]. This is especially true in countries where tap water is controlled more frequently and by more rigorous standards than bottled water [77]. As a result, safe tap water implies less need for bottled water in terms of healthy consumption [74]. In any case, among the many studies, relatively few explore pro-environment attitudes as motivations for reducing BWC [43,44,76].

Of the numerous theoretical frameworks that have been developed to explain certain behaviours, this study adopts TPB. The main reason is because of the scarcity of research that applies TPB to BWC. Xu and Lin [78] and Qian [74] are rare exceptions. However, these two studies focus mainly on factors influencing intention to buy bottled water without relating them to pro-environment motivations. To fill the gap, the current study developed a model explaining how individuals decide whether to reduce BWC out of environmental concern, focusing both on intentions and behaviour, by using the extended TPB model proposed by Chen and Tung [21]. Our study contributes to the literature on consumer behaviour (in particular, behaviour related to pro-environment motivations) and on environmental psychology, as TPB is an important part of environmental psychology [79]. Chen and Tung [21] initially used the extended TPB model to explain intention to visit green hotels. By successfully applying this model to intention to reduce BWC, our study proves that the extended TPB model can be used in different domains.

Our empirical results show that environmental concern is positively related to intention to reduce BWC. This relation is moderated by attitude towards BWC, subjective norms concerning reduction in BWC, perceived behavioural control, and perceived moral obligation. In addition, our findings verify that intention to reduce BWC determines whether individuals drink filtered tap water. The statistical significance of all the posited relations in the model supports the idea that the extended TPB is a useful tool in understanding both people’s intentions and their behaviour regarding reducing BWC.

In more detail, the empirical results indicate that a consumer’s environmental concern is positively related to their attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and moral obligation regarding reducing BWC. The results are in line with those of Chen and Tung [21], whose work, as noted, our study borrowed the extended TPB model from. These results contribute to the literature that uses the TPB framework to investigate intention to reduce BWC. Our study extends Xu and Lin’s [78] and Qian’s [74] studies, in which the construct of environmental concern was not included.

Our findings also support the assumption that attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and moral obligation predict intention to reduce BWC. We can conclude that the more positive an individual’s attitude is towards reducing BWC, the more likely they will be to intend to reduce BWC. Attitude turned out to be the strongest predictor of intention to reduce BWC. We can conclude that the strong belief of individuals that their actions can help protect the environment (reduce environmental pollution, reduce wasteful usage of natural resources) is paramount in affecting their intention to reduce BWC. This result is in line with previous studies (using the TPB model), such as those on intention to visit green hotels [21,53,54], intention to use green IT [45], intention to choose organic items on menus [55], and intention to use less water in order to conserve water [80]. In contrast, and surprisingly, Xu and Lin [78] found that attitude towards BWC is irrelevant to purchasing intention.

Our study also highlights the positive impact that subjective injunctive norms have on intention to reduce BWC. This finding supports the previous studies that found that subjective norms are positively related to intention to engage in eco-friendly behaviour, such as Xu and Lin [78] in the case of bottled water, de Leeuw et al. [52] in the case of high schoolers’ intention to engage in pro-environment behaviour, Yadav and Pathak [57] in the case of young consumers’ intention to purchase green products, and Han and Kim [53] in the case of intention to visit green hotels. We can conclude that the more a person feels pressure from important and valued people in their social network to reduce BWC, the more likely they will be to intend to reduce BWC. However, this particular relation turned out to be the weakest (of all those influencing intention to reduce bottled water consumption). This finding is in line with the analysis carried out by Armitage and Conner [81]. According to these authors, who used TPB as the theoretical framework, the subjective norm construct is a weak predictor of intentions. They attributed the result mostly to poor measurement. On the other hand, other studies provide evidence that social norms are strong predictors of environmental behaviours [82] such as garbage avoidance and selection, saving of resources and handling of toxic substances [83], and recycling [84,85]. The strong influence of social norms is present among young people according to Sears [86], who claims that young people have a less developed sense of self and, therefore, might be more susceptible to social influences. This influence may also be limited by our culture of self-reliance and individualism.

Our study also found a positive relation between perceived behavioural control and intention to reduce BWC. In other words, the more a person is convinced that purchasing bottled water is only up to them, the more likely they will be to intend to reduce BWC. This relation was also proven by Xu and Lin [78], but in a slightly different way. In our study, the lower the level of behavioural control is, the stronger the intention to buy bottled water is. Similar results were obtained in other studies that utilised TPB. Prendergast and Tsang [62] reported a very strong positive relation between behavioural control and socially responsible consumption. One of the dimensions of socially responsible consumption is intention to avoid or minimise use of products with adverse environmental impact.

Given that we employed an extended TPB model, we assumed that perceived moral obligations would influence intention to reduce BWC. Our results prove that the assumption is right. We can conclude that the more a person is aware that overexploitation of limited natural resources (and the future of our planet) is at stake, the more likely they will be to intend to reduce BWC. This relation is supported in the case of green hotels [21].

Previous researchers reported an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption [87]. This study, however, reveals a strong relation between intention to reduce BWC and pro-environment behaviour such as drinking filtered tap water. In other words, we proved that individuals that intend to engage in some sort of pro-environment behaviour (reduction in plastic usage) behave nearly accordingly. Although the relation between intention and behaviour is not always supported in our study, our study is in line with research that demonstrates a positive relation between intentions and behaviour in a variety of spheres [88,89,90].

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Our findings validate the assumption that—provided that an individual is concerned about the environment—their subjective norms push them to reduce BWC. They also demonstrate that if the individual perceives themself as having behavioural control over BWC, feels a moral obligation to reduce BWC, and, most importantly, has a positive attitude towards reducing BWC, it will result in intention to reduce BWC and, in turn, increased consumption of filtered tap water. Similarly, Qian [74] found that environmental concern is negatively correlated with drinking bottled water.

This study exhibits some limitations. Firstly, it relies on a self-reported questionnaire to investigate both intentions and behaviour. Future studies should focus especially on people’s actual behaviour (as opposed to self-reported) with respect to reducing BWC. That would make it possible to test for the existence and the extent of an intention–behaviour gap in this context.

The next limitation stems from the fact that the respondents were young (mean age of 24.5 years). However, young people are more environmentally concerned than older generations. This sample bias implies that the study’s results are not necessarily generalisable to the general Polish population. Future research utilising the TPB framework should include respondents representing all age groups.

Another limitation is that the study was conducted in only one country. Studies investigating several countries would be more insightful. For instance, countries where environmental concern is low or moderate, such as Poland [35], should be compared with nations with more environmental concern. Additionally, countries (mostly European) with clean, safe, and reliable tap water [76] should be compared with countries with low-quality tap water.

The limited degree to which variability of intention (R2 = 0.62) and behaviour (R2 = 0.43) are explained in this study indicates that future studies should assume that people’s intentions and behaviour depend on a broad range of factors not included in this study. Future research utilising the TPB model should investigate which factors (for instance, health, habit, convenience, and costs) influence the extent to which people reduce their consumption of single-use bottled water. What is more, our study did not include situational factors (for example, quality of tap water, including degree of contamination; whether an individual is visiting an exotic country; and limited choice, such as on long flights). However, situational factors may decrease or increase the gap between intentions and pro-environment behaviour. Incorporating such factors would ensure a more comprehensive understanding of decision making with respect to BWC [53].

Future research should also investigate whether pro-environment behaviours can be conceptualised as altruistic or egoistic. Ebreo et al. [82] found that they are altruistic in the sense that those who care about the environment do it to protect society. Furthermore, such people do not expect to receive any rewards. On the other hand, according to Tezer and Bodur [91], pro-environment behaviour is driven by a so-called warm glow, defined as feeling good about oneself after engaging in pro-social behaviour [92,93]. This finding implies egoistic reasons for protecting the environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.B.; methodology: B.B. and A.S.; software: A.S.; formal analysis: A.S.; investigation: B.B., A.S., B.P., and K.S.; writing—original draft preparation: B.B., A.S., B.P., and K.S.; writing—review and editing: B.B., A.S., and B.P.; project administration: B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was co-financed within the Regional Initiative for Excellence programme of the Minister of Science and Higher Education of Poland, years 2019–2022, grant no. 004/RID/2018/19, financing 3,000,000 PLN.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Wroclaw Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (Approval Notice no. 1/2021, date of approval—11 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement scale construct used in the study.

Table A1.

Measurement scale construct used in the study.

| Variable | Statements | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental concern (EC) | EC1. In order to survive, humans must live in harmony with nature. EC2. I think environmental problems are very important. EC3. I think environmental problems cannot be ignored. EC4. I think we should care about environmental problems. | [21,94] |

| Attitude towards reduction in bottled water consumption (AT) | AT1. I believe that reducing my bottled water consumption will help in reducing environmental pollution. AT2. I believe that reducing my bottled water consumption will help in reducing wasteful usage of natural resources. AT3. I believe that reducing my bottled water consumption will help in natural resource protection. | [51] |

| Subjective injunctive norms (SN) | SIN1. Most people who are important to me think I should reduce bottled water consumption. SIN2. Most people who are important to me would want me to reduce bottled water consumption. SIN3. People whose opinions I value would prefer that I reduce bottled water consumption. | [21,53] |

| Perceived behavioural control (PBC) | PBC1. Whether or not I drink a bottled water is completely up to me. PBC2. I am confident that if I want, I can reduce bottled water consumption. PBC3. I have opportunities to reduce bottled water consumption. PBC4. The water I drink, I acquire myself. | [21,53] |

| Perceived moral obligation (PMO) | PMO1. Everybody is obligated to treasure natural resources. PMO2. Everybody should save natural resources because they are limited. | [21,80] |

| Intention to reduce BWC (IR) | IR1. I plan to reduce bottled water consumption. IR2. I am willing to reduce bottled water consumption. IR3. I will make an effort to reduce bottled water consumption. | [21,53] |

| Non-bottled water consumption behaviour (NBWCB) | BWCB1. I drink a lot of non-bottled water. BWCB2. I use mainly bottles filtering water. BWCB3. I use filtered water mainly. | Own elaboration |

References

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parag, Y.; Opher, T. Bottled drinking water: A review. In Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324538028_Bottled_Drinking_Water_A_Review (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Statistica. Per Capita Consumption of Bottled Water Worldwide in 2018, by Leading Countries. 2019. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/183388/per-capita-consumption-of-bottled-water-worldwide-in-2018/ (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- The Business Research Company. The Global Bottled Water Market: Expert Insights & Statistics. Available online: https://blog.marketresearch.com/the-global-bottled-water-market-expert-insights-statistics (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Dutta, S.; Nadaf, M.B.; Mandal, J.N. An overview on the use of waste plastic bottles and fly ash in civil engineering applications. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royte, E. Eat Your Food, and the Package Too. 2019. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/future-of-food/food-packaging-plastics-recycle-solutions/ (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Díez, J.; Antigüedad, I.; Agirre, E.; Rico, A. Perceptions and consumption of bottled water at the University of the Basque Country: Showcasing tap water as the real alternative towards a water-sustainable university. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.Y.; Truong, D. Passengers’ intentions to use low-cost carriers: An extended theory of planned behavior model. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 69, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, D. Policy implications of the purchasing intentions towards energy-efficient appliances among China’s urban residents: Do subsidies work? Energy Policy 2017, 102, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, W.; Jin, Z.; Wang, Z. Influence of environmental concern and knowledge on households’ willingness to purchase energy-efficient appliances: A case study in Shanxi, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Muhmin, A.G. Explaining consumers’ willingness to be environmentally friendly. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Aksoy, Ş.; Caber, M. The effect of environmental concern and scepticism on green purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2013, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Wiener, J.L.; Cobb-Walgren, C. The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Joarder, M.H.R.; Ratan, S.R.A. Consumers’ anti-consumption behavior toward organic food purchase: An analysis using SEM. Br. Food J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. An application of theory of planned behavior to predict young Indian consumers’ green hotel visit intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand consumers’ intentions to visit green hotels in the Chinese context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2810–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, R.; Weigel, J. Environmental concern: The development of a measure. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.-S.; Choi, J.-G. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, N.; Gärling, T. Environmental concern: Conceptual definitions, measurement methods, and research findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, G. Criteria for a theory of responsible consumption. J. Mark. 1973, 37, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T.C.; Taylor, J.R.; Ahmed, S.A. Ecologically concerned consumers: Who are they? J. Mark. 1974, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Socially responsible organizational buying: Environmental concern as a noneconomic buying criterion. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, K. Examining environmental concern in developed, transitioning and developing countries. World Values Res. 2012, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Egea, J.M.; Garcia-de-Frutos, N.; Antolin-Lopez, R. Why do some people do “more” to mitigate climate change than others? Exploring heterogeneity in psycho-social associations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, J.; Krekel, C.; Tiefenbach, T.; Ziebarth, N.R. How natural disasters can affect environmental concerns, risk aversion, and even politics: Evidence from Fukushima and three European countries. J. Popul. Econ. 2015, 28, 1137–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainieri, T.; Barnett, E.G.; Valdero, T.R.; Unipan, J.B.; Oskamp, S. Green buying: The influence of environmental concern on consumer behavior. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 137, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Suki, N. Consumer environmental concern and green product purchase in Malaysia: Structural effects of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Gouveia, V.V.; Cameron, L.D.; Tankha, G.; Schmuck, P.; Franěk, M. Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Values, environmental concern, and environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2016, 36, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiaslis, A.; Krontalis, A.K. Green consumption behavior antecedents: Environmental concern, knowledge, and beliefs. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding environmentally friendly products: An empirical analysis of German consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, T. The impact of values, environmental concern, and willingness to accept economic sacrifices to protect the environment on tourists’ intentions to buy ecologically sustainable tourism alternatives. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W. Culture and ecology: A cross-national study of the determinants of environmental sustainability. Manag. Int. Rev. 2005, 45, 349–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L.A.; Cain, O.L.; Mullally, R.A.; Holliday, K.S.; Wernham, A.G.H.; Baillie, P.D.; Greenfield, S.M. Health beliefs about bottled water: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levêque, J.G.; Burns, R.C. Predicting water filter and bottled water use in Appalachia: A community-scale case study. J. Water Health 2017, 15, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S. Exploring beliefs about bottled water and intentions to reduce consumption: The dual-effect of social norm activation and persuasive information. Environ. Behav. 2013, 47, 526–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantine, P.W.; Ozanne, L.K.; Bayfield, R. Why buy free? Exploring perceptions of bottled water consumption and its environmental consequences. Sustainability 2019, 11, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orset, C.; Barret, N.; Lemaire, A. How consumers of plastic water bottles are responding to environmental policies? Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dezdar, S. Green information technology adoption: Influencing factors and extension of theory of planned behavior. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Meng, B.; Kim, W. Emerging bicycle tourism and the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afroz, R.; Masud, M.; Akhtar, R.; Islam, M.; Duasa, J. Consumer purchase intention towards environmentally friendly vehicles: An empirical investigation in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2015, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S. Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, G. Pro-environmental behavior in Egypt: Is there a role for Islamic environmental ethics? J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 65, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, P.O.D.; Rebelo, E.; Reis, E.; Menezes, J. Combining behavioral theories to predict recycling involvement. Environ. Behav. 2016, 37, 364–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B.; Kumar, S. Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers’ attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model approach to consumer behavior regarding organic menus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Tarafder, T.; Pearson, D.; Henryks, J. Intention-behaviour gap and perceived behavioural control-behaviour gap in theory of planned behaviour: Moderating roles of communication, satisfaction and trust in organic food consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiak, B.; Szymkowiak, A.; Horska, E.; Raszka, N.; Żelichowska, E. Towards building sustainable consumption: A study of second-hand buying intentions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Mohammed Rafiul Huque, S.; Haroon Hafeez, M.; Noor Mohd Shariff, M. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwir, N.S.; Hamzah, M.I. Predicting purchase intention of hybrid electric vehicles: Evidence from an emerging economy. World Electr. Veh. J. 2020, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, C.; Dong, H.; Lee, Y.-A. Factors influencing consumers’ purchase intention of green sportswear. Fash. Text. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, G.P.; Tsang, A.S.L. Explaining socially responsible consumption. J. Consum. Mark. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K. Predicting the consumption of expired food by an extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłos, L. Spożycie wody butelkowanej w Polsce i jej wpływ na środowisko przyrodnicze. Barom. Reg. 2016, 14, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; p. 761. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 6th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.; Baumgartner, H. On the use of structural equation models in marketing modeling. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2000, 17, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria, M.; Pidgeon, N.; Hunter, P. Perception of tap water risks and quality: A structural equation model approach. Water Sci. Technol. 2005, 52, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria, M.F. Bottled water versus tap water: Understanding consumers’ preferences. J. Water Health 2006, 4, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrier, C. Bottled water: Understanding a social phenomenon. Ambio 2001, 30, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.; Palaniappan, M. Peak water limits to freshwater withdrawal and use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11155–11162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, N. Bottled water or tap water? A comparative study of drinking water choices on university campuses. Water 2018, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas, A.B.; Sutherland, J.P. A survey of the microbiological quality of bottled water sold in the UK and changes occurring during storage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1999, 48, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, I.R.; Purcărea, V.; Gheorghe, C.M. Pro-Environmental Behavior and Bioeconomy: Reflections on Single-Bottled Water Consumption. Amfiteatru Econ. 2019, 21, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, E. Bottled Water: Pure Drink or Pure Hype? Natural Resources Defines Council (NRDC); New York, NY, USA, 1999. Available online: https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/bottled-water-pure-drink-or-pure-hype-report.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Xu, X.; Lin, C.A. Effects of cognitive, affective, and behavioral factors on college students’ bottled water purchase intentions. Commun. Res. Rep. 2018, 35, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F. Selecting environmental psychology theories to predict people’s consumption intention of locally produced organic foods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.-P. Predicting intentions to conserve water from the theory of planned behavior, perceived moral obligation, and perceived water right. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 1058–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebreo, A.; Vining, J.; Cristancho, S. Responsibility for environmental problems and the consequences of waste reduction: A test of the norm-activation model. J. Environ. Syst. 2003, 29, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinheider, B.; Fay, D.; Hilburger, T.; Hust, I.; Prinz, L.; Vogelgesang, F.; Hormuth, S. Soziale Normen als Prediktoren von umweltbezogenemVerhalten. Z. Sozialpsychol. 1999, 30, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.R.; Nielsen, J.M. Recycling as altruistic behavior: Normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, J.; Ebreo, A. Predicting recycling behavior from global and specific environmental attitudes and changes in recycling opportunities. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1580–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, D. College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology’s view of human nature. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Louis, W. Do as we say and as we do: The interplay of descriptive and injunctive group norms in the attitude-behaviour relationship. Brit. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 647–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.; Read, A. Using the theory of planned behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezer, A.; Bodur, H.O. The greenconsumption effect: How using green products improves consumption experience. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 47, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. J. Polit. Econ. 1989, 97, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. Econ. J. 1990, 100, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S. Environmental concern, attitude toward frugality, and ease of behavior as determinants of pro-environmental behavior intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).