Environmental Assessment and Sustainable Development in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Studies

2.1. State-Level Performance Measurement

2.2. Political and Spatial Contexts on Climate/Environmental Policy

3. Underlying Concepts

4. Method

- : A column vector of m inputs,

- : The i th input of the j th DMU at the t th period,

- : A column vector of s desirable outputs,

- : The r th desirable output of the j th DMU at the t th period,B: A column vector of h undesirable outputs,

- : The f th undesirable output of the j th DMU at the t th period,

- : An inefficiency score of the k th DMU at the t th period,

- : A slack variable of the i th input,

- : A slack variable of the r th desirable output,

- : A slack variable of the f th undesirable output,

- : A vector of intensity variables on the j th DMU at the z th period,

- : A prescribed very small number,

- : A data range related to the i th input

- : A data range related to the f th undesirable output,

- t: The observed t th period (t = 1,.., T).

5. An Illustrative Example

5.1. Data

5.2. Efficiency/Index Measures

5.3. Statistical Test

5.4. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, A.; Justwan, F.; Carlisle, J.E.; Clark, M. Polarization politics and hopes for a green agenda in the United States. Environ. Politics 2019, 29, 719–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarri, D.; Gelman, A. Partisans without Constraint: Political Polarization and Trends in American Public Opinion. Am. J. Sociol. 2008, 114, 408–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Xiao, C.; Dunlap, R.E. Political polarization on support for government spending on environmental protection in the USA, 1974–2012. Soc. Sci. Res. 2014, 48, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guber, D.L. A Cooling Climate for Change? Party Polarization and the Politics of Global Warming. Am. Behav. Sci. 2012, 57, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Urpelainen, J. Environmental public opinion in U.S. states, 1973–2012. Environ. Politics 2017, 27, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. Governing the global climate commons: The political economy of state and local action, after the U.S. flip-flop on the Paris Agreement. Energy Policy 2018, 118, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J. The next phase of the energy transition and its implications for research and policy. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zalk, J.; Behrens, P. The spatial extent of renewable and non-renewable power generation: A review and meta-analysis of power densities and their application in the U.S. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, S.; La Croix, S.; Coffman, M. Understanding changes in electric vehicle policies in the U.S. states, 2010–2018. Transp. Policy 2021, 103, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S.; Dinc, M. Telecommunications and Regional Development: Evidence from the U.S. States. Econ. Dev. Q. 2002, 16, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Joo, S.-J. Measuring the Performance of the U.S. Correctional Systems at the State Level. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2020, 22, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Murova, O.I. Productive Efficiency of Public Expenditures: A Cross-state Study. State Local Gov. Rev. 2015, 47, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.J.; Sharma, S.; Jain, S.K. Using patents and publications to assess R&D efficiency in the states of the USA. World Pat. Inf. 2011, 33, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Drivas, K.; Economidou, C.; Tsionas, E.G. Production of output and ideas: Efficiency and growth patterns in the United States. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhart, R.S. Non-parametric frontier estimation of health care efficiency among US states, 2002–2008. Health Syst. 2017, 6, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhart, R.; Michieka, N. Efficiency of American states after implementation of the patient protection and affordable care act (PPACA) from 2014 to 2017. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 1959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Lim, S.H.; Egilmez, G.; Szmerekovsky, J. Environmental efficiency assessment of U.S. transport sector: A slack-based data envelopment analysis approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 61, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.E.; Polemis, M.L. The impact of economic growth on environmental efficiency of the electricity sector: A hybrid window DEA methodology for the USA. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 211, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmichael, J.T.; Brulle, R.J. Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: An integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001–2013. Environ. Politics 2017, 26, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, B.G. States on Steroids: The Intergovernmental Odyssey of American Climate Policy. Rev. Policy Res. 2008, 25, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H. Clean energy policies and green jobs: An evaluation of green jobs in U.S. metropolitan areas. Energy Policy 2013, 56, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, P.G.; Millimet, D.L. Strategic Interaction and the Determination of Environmental Policy across U.S. States. J. Urban Econ. 2002, 51, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Hughes, K.; Rickerson, W.; Kurdgelashvili, L. American policy conflict in the greenhouse: Divergent trends in federal, regional, state, and local green energy and climate change policy. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 4555–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.T.; Burkardt, N.; King, D. Watershed Management and Organizational Dynamics: Nationwide Findings and Regional Variation. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwickl, K.; Ash, M.; Boyce, J.K. Regional variation in environmental inequality: Industrial air toxics exposure in U.S. cities. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 107, 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.C.; Keim, B.D. Regional variation in perceptions about climate change. Int. J. Climatol. 2009, 29, 2348–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, P.D.; Mildenberger, M.; Marlon, J.R.; Leiserowitz, A. Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Goto, M. Performance assessment of Japanese electric power industry: DEA measurement with future impreciseness. Energies 2020, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Goto, M. Environmental Assessment on Energy and Sustainability by Data Envelopment Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, P.H.; Marques, A.C.; Shahbaz, M. The role of globalisation, de jure and de facto, on environmental performance: Evidence from developing and developed countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, D.C.; Porter, M.E. National environmental performance: An empirical analysis of policy results and determinants. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2005, 10, 391–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Hua, H.; Dong, Z.; Hao, C. Environmental Performance Index at the Provincial Level for China 2006–2011. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 75, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yang, M. Analysis on China’s eco-innovations: Regulation context, intertemporal change and regional differences. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 247, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah, M.; Christopher, G. Public and local government leader opinions on environmental federalism: Comparing issues and national contexts. State Local Gov. Rev. 2016, 48, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Peifer, J.L.; Khalsa, S.; Ecklund, E.H. Political conservatism, religion, and environmental consumption in the United States. Environ. Politics 2016, 25, 661–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Tadiparthi, G.R. An agent-based decision support system for wholesale electrify market. Decis. Supp. Syst. 2008, 44, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.E.; Polemis, M.L. The impact of market structure on environmental efficiency in the United States: A quantile approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Yuan, Y. Social sustainability measured by intermediate approach for DEA environmental assessment: Chinese regional planning for economic development and pollution prevention. Energy Econ. 2017, 66, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Yuan, Y.; Goto, M. A literature study for DEA applied to energy and environment. Energy Econ. 2017, 62, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Ryu, Y. Performance Assessment of the semiconductor industry: Measured by DEA environmental assessment. Energies 2020, 13, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Liu, X.; Li, A. Evaluating the performance of Chinese fossil fuel power by data envelopment analysis: An application of three intermediate approaches in a time horizon. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 227, 121992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Ryu, Y.; Yun, J.-Y. Coronavirus-19 response and prospects of clean/sustainable energy transition in industrial nations: New Environmental assessment. Energies 2021, 14, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biden Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution and Environmental Justice. Available online: https://joebiden.com/climate-plan/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

| Author(s) | Method | Summary | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yilmaz & Dinc [10] | Conventional DEA | This study explored 48 states’ telecommunications infrastructure use performance over the period of 1984–1997. | Private, public, and telecommunications capital stocks and labor | Total value added of states’ private industries |

| Lee & Joo [11] | Conventional DEA | This study examined 50 states’ operational performance of correctional facilities in 2005. | Capacity and expenditure | Number of inmates and recidivism |

| Khan & Murova [12] | Conventional DEA | This study looked into 50 states’ operational performance over the period of 1992–2012. | State expenditure, employment, and population | Gross state product |

| Thomas et al. [13] | Efficiency ratio | This study shed light on changes of 50 states’ R&D efficiency ratios between 2004 and 2008. | R&D expenditure | Patents granted and scientific publications |

| Drivas et al. [14] | SFA | This study measured 50 states’ output and knowledge production efficiencies over the period of 1993–2006. | Gross capital stock, the number of workers, business R&D stock, and the number of scientists and engineers | Gross state product and patents |

| Gearhart [15] | Hyperbolic order-α estimator | This study analyzed 50 states’ health care efficiency over the period of 2002–2008. | Vaccine, citizens/hospital, inpatient days, hospital beds, cost, etc. | Infant/teen survival rate and life expectancy |

| Gearhart & Michieka [16] | Conditional order-m estimator | This study analyzed 50 states’ health care efficiency over the period of 2014–2017. | Healthcare costs and the fraction of individuals with some college | Years of life gained and the fraction of infants born normal birthweight |

| Park et al. [17] | Non-radial SBM-DEA | This study evaluated 50 states’ environmental performance in the transportation sector over the period of 2004–2012. | Capital expense, energy consumption and labor in the transportation sector | Transportation value added and CO2 emissions |

| Halkos & Polemis [18] | Window DEA | This study assessed 50 states’ environmental efficiency in the power generation sector over the period of 2000–2012. | Total energy transmission and total operating cost | Use of net capacity, CO2, SO2 and NOx emissions |

| State | Presidential Elections | Gubernatorial Elections | State | Presidential Elections | Gubernatorial Elections | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winners | Transition | Winners | Transition | Winners | Transition | Winners | Transition | ||

| Alabama | RRR | R to R | RRRR | R to R | Montana | RRR | R to R | DDD | D to D |

| Alaska | RRR | R to R | RRIR | R to R | Nebraska | RRR | R to R | RRRR | R to R |

| Arizona | RRR | R to R | DRRR | D to R | Nevada | DDD | D to D | RRRD | R to D |

| Arkansas | RRR | R to R | DDRR | D to R | New Hampshire | DDD | D to D | DDRR | D to R |

| California | DDD | D to D | RDDD | R to D | New Jersey | DDD | D to D | DRRD | D to D |

| Colorado | DDD | D to D | DDDD | D to D | New Mexico | DDD | D to D | DRRD | D to D |

| Connecticut | DDD | D to D | RDD | R to D | New York | DDD | D to D | DDDD | D to D |

| Delaware | DDD | D to D | DDD | D to D | N. Carolina | DRR | D to R | DRD | D to D |

| Florida | DDR | D to R | RRRR | R to R | N. Dakota | RRR | R to R | RRR | R to R |

| Georgia | RRR | R to R | RRRR | R to R | Ohio | DDR | D to R | DRRR | D to R |

| Hawaii | DDD | D to D | RDDD | R to D | Oklahoma | RRR | R to R | DRRR | D to R |

| Idaho | RRR | R to R | RRRR | R to R | Oregon | DDD | D to D | DDDD | D to D |

| Illinois | DDD | D to D | DDRD | D to D | Pennsylvania | DDR | D to R | DRDD | D to D |

| Indiana | DRR | D to R | RRR | R to R | Rhode Island | DDD | D to D | RIDD | R to D |

| Iowa | DDR | D to R | DRRR | D to R | S. Carolina | RRR | R to R | RRRR | R to R |

| Kansas | RRR | R to R | DRRD | D to D | S. Dakota | RRR | R to R | RRRR | R to R |

| Kentucky | RRR | R to R | DDR | D to R | Tennessee | RRR | R to R | DRRR | D to R |

| Louisiana | RRR | R to R | RRD | R to D | Texas | RRR | R to R | RRRR | R to R |

| Maine | DDD | D to D | DRRD | D to D | Utah | RRR | R to R | RRR | R to R |

| Maryland | DDD | D to D | DDRR | D to R | Vermont | DDD | D to D | RDDDRR | R to R |

| Massachusetts | DDD | D to D | DDRR | D to R | Virginia | DDD | D to D | DRDD | D to D |

| Michigan | DDR | D to R | DRRD | D to D | Washington | DDD | D to D | DDD | D to D |

| Minnesota | DDD | D to D | RDDD | R to D | W. Virginia | RRR | R to R | DDD | D to D |

| Mississippi | RRR | R to R | RRR | R to R | Wisconsin | DDR | D to R | DRRD | D to D |

| Missouri | RRR | R to R | DDR | D to R | Wyoming | RRR | R to R | DRRR | D to R |

| EDA Region | EPA Region | State |

|---|---|---|

| Philadelphia Regional Office | Region 1 | Connecticut |

| Maine | ||

| Massachusetts | ||

| New Hampshire | ||

| Rhode Island | ||

| Vermont | ||

| Region 2 | New Jersey | |

| New York | ||

| Region 3 | Delaware | |

| Maryland | ||

| Pennsylvania | ||

| Virginia | ||

| West Virginia | ||

| Atlanta Regional Office | Region 4 | Alabama |

| Florida | ||

| Georgia | ||

| Kentucky | ||

| Mississippi | ||

| North Carolina | ||

| South Carolina | ||

| Tennessee | ||

| Chicago Regional Office | Region 5 | Illinois |

| Indiana | ||

| Michigan | ||

| Minnesota | ||

| Ohio | ||

| Wisconsin | ||

| Austin Regional Office | Region 6 | Arkansas |

| Louisiana | ||

| New Mexico | ||

| Oklahoma | ||

| Texas | ||

| Region 7 | Iowa | |

| Kansas | ||

| Missouri | ||

| Nebraska | ||

| Denver Regional Office | Region 8 | Colorado |

| Montana | ||

| North Dakota | ||

| South Dakota | ||

| Utah | ||

| Wyoming | ||

| Region 9 | Arizona | |

| California | ||

| Hawaii | ||

| Nevada | ||

| Seattle Regional Office | Region 10 | Alaska |

| Idaho | ||

| Oregon | ||

| Washington |

| State | Input | Desirable Output | Undesirable Output | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (Thousands) | Expenditure ($ Million) | Energy Consump. (Billion BTU) | Patent (Grants) | GSP ($ Million) | CO2 (MMT) | |

| (a) | ||||||

| Arizona | 7158 | 35,147 | 1,487,797 | 2812 | 350,718 | 91 |

| California | 39,462 | 269,668 | 7,966,578 | 43,960 | 2,975,083 | 376 |

| Colorado | 5691 | 39,814 | 1,513,286 | 3259 | 372,453 | 90 |

| Connecticut | 3572 | 33,149 | 753,010 | 2977 | 279,782 | 38 |

| Delaware | 957 | 10,847 | 290,283 | 285 | 74,187 | 14 |

| Georgia | 10,511 | 49,509 | 2,876,097 | 3064 | 602,024 | 135 |

| Hawaii | 1421 | 15,199 | 292,895 | 136 | 93,101 | 20 |

| Illinois | 12,723 | 72,783 | 4,011,952 | 5655 | 863,040 | 215 |

| Maine | 1335 | 8412 | 395,251 | 228 | 64,557 | 15 |

| Maryland | 6036 | 43,796 | 1,361,165 | 2042 | 411,619 | 60 |

| Massachusetts | 6883 | 57,124 | 1,458,647 | 7687 | 570,464 | 65 |

| Michigan | 9984 | 56,613 | 2,894,187 | 7293 | 521,803 | 164 |

| Minnesota | 5606 | 39,819 | 1,913,919 | 4513 | 371,930 | 94 |

| Nevada | 3027 | 14,843 | 727,227 | 745 | 169,180 | 39 |

| New Hampshire | 1349 | 6131 | 324,693 | 998 | 84,584 | 15 |

| New Jersey | 8886 | 60,775 | 2,240,709 | 4682 | 612,979 | 111 |

| New Mexico | 2093 | 20,402 | 702,827 | 535 | 100,080 | 47 |

| New York | 19,530 | 163,744 | 3,854,184 | 9780 | 1,705,010 | 172 |

| Oregon | 4182 | 40,619 | 1,012,242 | 3522 | 241,978 | 40 |

| Pennsylvania | 12,801 | 84,908 | 3,961,566 | 4456 | 778,375 | 227 |

| Rhode Island | 1058 | 9262 | 197,377 | 415 | 59,925 | 12 |

| Vermont | 624 | 5675 | 139,153 | 388 | 32,981 | 6 |

| Virginia | 8501 | 52,078 | 2,401,238 | 2542 | 533,510 | 105 |

| Washington | 7524 | 46,021 | 2,078,665 | 7445 | 575,417 | 82 |

| Wisconsin | 5807 | 48,199 | 1,885,868 | 2702 | 337,553 | 103 |

| Average | 7469 | 51,381 | 1,869,633 | 4885 | 511,293 | 93 |

| (b) | ||||||

| Alabama | 4888 | 27,475 | 1,954,823 | 510 | 221,031 | 114 |

| Alaska | 735 | 10,291 | 609,786 | 57 | 54,293 | 36 |

| Arkansas | 3010 | 25,506 | 1,119,701 | 403 | 127,761 | 72 |

| Florida | 21,244 | 78,523 | 4,281,336 | 4893 | 1,050,298 | 233 |

| Idaho | 1751 | 7963 | 553,287 | 843 | 79,091 | 19 |

| Indiana | 6695 | 33,621 | 2,837,602 | 2265 | 368,425 | 192 |

| Iowa | 3149 | 23,382 | 1,616,101 | 1056 | 190,147 | 85 |

| Kansas | 2911 | 15,911 | 1,134,492 | 894 | 171,719 | 63 |

| Kentucky | 4461 | 34,053 | 1,743,944 | 745 | 207,849 | 123 |

| Louisiana | 4660 | 31,253 | 4,403,154 | 490 | 253,236 | 258 |

| Mississippi | 2989 | 19,118 | 1,192,670 | 208 | 113,579 | 71 |

| Missouri | 6122 | 26,038 | 1,847,810 | 1406 | 317,949 | 124 |

| Montana | 1061 | 6952 | 435,230 | 172 | 50,692 | 32 |

| Nebraska | 1916 | 12,141 | 914,565 | 314 | 124,705 | 53 |

| N. Carolina | 10,382 | 47,795 | 2,616,133 | 3781 | 567,452 | 122 |

| N. Dakota | 758 | 5889 | 660,959 | 123 | 56,287 | 55 |

| Ohio | 11,676 | 69,682 | 3,755,870 | 4608 | 675,030 | 211 |

| Oklahoma | 3940 | 22,669 | 1,706,535 | 614 | 198,596 | 100 |

| S. Carolina | 5084 | 25,257 | 1,671,781 | 1142 | 235,287 | 75 |

| S. Dakota | 879 | 4457 | 396,837 | 157 | 53,239 | 16 |

| Tennessee | 6772 | 33,562 | 2,255,868 | 1289 | 362,737 | 97 |

| Texas | 28,629 | 114,592 | 14,258,824 | 11,359 | 1,795,635 | 823 |

| Utah | 3154 | 14,789 | 835,121 | 1795 | 181,623 | 61 |

| W. Virginia | 1804 | 16,857 | 832,914 | 152 | 77,633 | 89 |

| Wyoming | 578 | 4425 | 558,594 | 118 | 39,703 | 64 |

| Average | 5570 | 28,488 | 2,167,757 | 1576 | 302,960 | 128 |

| State | Output | State | Output | State | Output | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSP ($ Million) | CO2 (MMT) | GSP ($ Million) | CO2 (MMT) | GSP ($ Million) | CO2 (MMT) | |||

| Arizona | 287,023 | 93 | New York | 1,405,735 | 170 | Louisiana | 230,649 | 253 |

| (35,701) | (3) | (181,537) | (5) | (11,677) | (8) | |||

| California | 2,378,366 | 371 | Oregon | 192,397 | 40 | Mississippi | 102,472 | 66 |

| (369,901) | (6) | (28,022) | (1) | (6464) | (4) | |||

| Colorado | 300,269 | 92 | Pennsylvania | 675,190 | 241 | Missouri | 281,455 | 129 |

| (41,370) | (3) | (66,497) | (13) | (22,228) | (6) | |||

| Connecticut | 253,028 | 36 | Rhode Island | 53,838 | 11 | Montana | 43,513 | 33 |

| (15,974) | (1) | (4087) | (1) | (4480) | (1) | |||

| Delaware | 65,142 | 14 | Vermont | 29,578 | 6 | Nebraska | 107,755 | 51 |

| (6038) | (1) | (2236) | (0) | (12,431) | (2) | |||

| Georgia | 486,445 | 145 | Virginia | 465,731 | 105 | N. Carolina | 475,184 | 127 |

| (67,949) | (14) | (40,253) | (3) | (55,673) | (7) | |||

| Hawaii | 78,317 | 19 | Washington | 443,099 | 78 | N. Dakota | 48,816 | 53 |

| (9248) | (0) | (73,307) | (4) | (9093) | (3) | |||

| Illinois | 750,271 | 225 | Wisconsin | 289,261 | 100 | Ohio | 574,078 | 226 |

| (72,389) | (11) | (30,245) | (3) | (64,807) | (15) | |||

| Maine | 56,007 | 17 | Alabama | 193,687 | 121 | Oklahoma | 175,884 | 104 |

| (4738) | (1) | (16,091) | (7) | (16,887) | (4) | |||

| Maryland | 354,469 | 63 | Alaska | 53,554 | 38 | S. Carolina | 192,027 | 76 |

| (36,743) | (5) | (3003) | (2) | (26,110) | (5) | |||

| Massachusetts | 473,342 | 67 | Arkansas | 112,736 | 66 | S. Dakota | 45,056 | 15 |

| (58,661) | (3) | (9882) | (4) | (5378) | (0) | |||

| Michigan | 444,015 | 161 | Florida | 850,014 | 230 | Tennessee | 302,121 | 103 |

| (51,995) | (5) | (114,589) | (6) | (38,863) | (4) | |||

| Minnesota | 314,641 | 93 | Idaho | 63,577 | 18 | Texas | 1,480,361 | 766 |

| (36,274) | (2) | (8347) | (1) | (195,335) | (41) | |||

| Nevada | 138,583 | 37 | Indiana | 314,810 | 199 | Utah | 141,672 | 63 |

| (16,208) | (2) | (33,301) | (13) | (22,173) | (3) | |||

| New Hampshire | 72,073 | 15 | Iowa | 165,018 | 84 | W. Virginia | 70,020 | 93 |

| (7637) | (1) | (18,500) | (5) | (4009) | (4) | |||

| New Jersey | 543,682 | 113 | Kansas | 146,999 | 68 | Wyoming | 38,029 | 65 |

| (43,957) | (4) | (15,432) | (5) | (1407) | (2) | |||

| New Mexico | 89,857 | 53 | Kentucky | 183,293 | 137 | |||

| (5267) | (4) | (16,538) | (12) | |||||

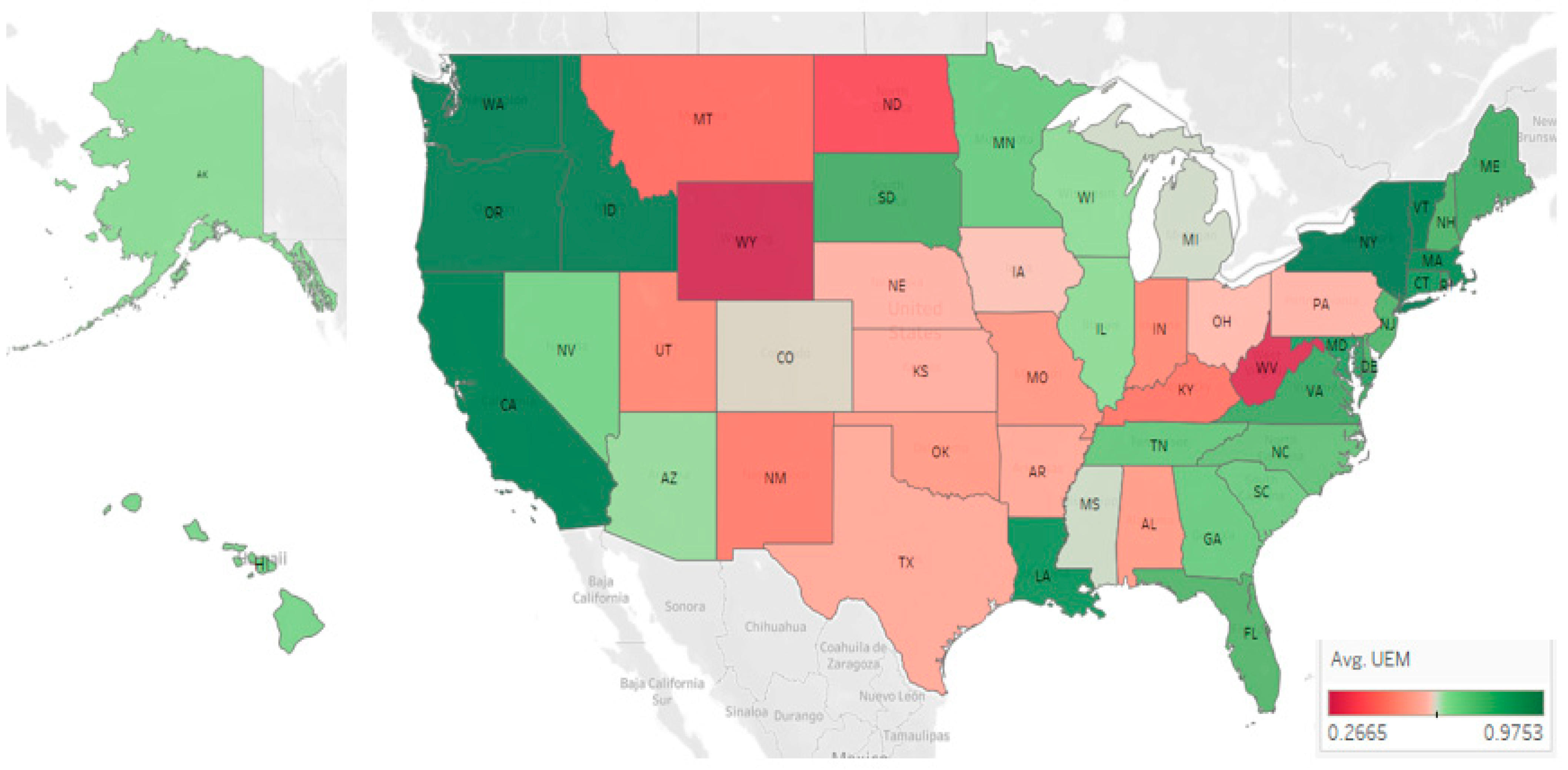

| UEM | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Arizona | 0.611 | (27) | 0.602 | (29) | 0.619 | (28) | 0.637 | (27) | 0.617 | (29) | 0.638 | (27) | 0.660 | (28) | 0.698 | (27) | 0.711 | (26) | 0.686 | (27) |

| California | 0.876 | (7) | 0.920 | (6) | 0.958 | (6) | 0.961 | (7) | 0.972 | (2) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.990 | (3) | 0.995 | (2) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.987 | (4) |

| Colorado | 0.572 | (31) | 0.573 | (31) | 0.591 | (32) | 0.595 | (30) | 0.606 | (30) | 0.614 | (30) | 0.630 | (31) | 0.646 | (31) | 0.658 | (30) | 0.670 | (29) |

| Connecticut | 0.852 | (9) | 0.848 | (9) | 0.863 | (7) | 0.886 | (8) | 0.876 | (9) | 0.880 | (8) | 0.873 | (10) | 0.932 | (9) | 0.959 | (8) | 0.911 | (9) |

| Delaware | 0.830 | (10) | 0.813 | (11) | 0.776 | (16) | 0.740 | (18) | 0.763 | (18) | 0.794 | (15) | 0.800 | (16) | 0.770 | (19) | 0.813 | (16) | 0.850 | (14) |

| Georgia | 0.620 | (26) | 0.621 | (26) | 0.662 | (24) | 0.715 | (21) | 0.732 | (21) | 0.731 | (19) | 0.750 | (21) | 0.754 | (21) | 0.766 | (22) | 0.792 | (21) |

| Hawaii | 0.637 | (23) | 0.617 | (27) | 0.610 | (30) | 0.633 | (28) | 0.648 | (25) | 0.685 | (24) | 0.695 | (26) | 0.745 | (22) | 0.783 | (20) | 0.786 | (22) |

| Illinois | 0.607 | (29) | 0.611 | (28) | 0.618 | (29) | 0.644 | (26) | 0.627 | (27) | 0.635 | (28) | 0.667 | (27) | 0.700 | (26) | 0.707 | (27) | 0.710 | (26) |

| Maine | 0.746 | (18) | 0.770 | (16) | 0.790 | (15) | 0.838 | (12) | 0.823 | (12) | 0.828 | (13) | 0.829 | (13) | 0.813 | (15) | 0.852 | (13) | 0.898 | (11) |

| Maryland | 0.754 | (17) | 0.779 | (14) | 0.813 | (13) | 0.856 | (10) | 0.876 | (10) | 0.854 | (10) | 0.883 | (9) | 0.901 | (11) | 0.984 | (5) | 0.904 | (10) |

| Massachusetts | 0.796 | (13) | 0.810 | (12) | 0.858 | (9) | 0.976 | (6) | 0.935 | (6) | 0.977 | (4) | 0.955 | (6) | 0.978 | (3) | 1.000 | (1) | 1.000 | (1) |

| Michigan | 0.567 | (32) | 0.582 | (30) | 0.609 | (31) | 0.622 | (29) | 0.619 | (28) | 0.629 | (29) | 0.622 | (33) | 0.657 | (30) | 0.657 | (31) | 0.650 | (32) |

| Minnesota | 0.658 | (22) | 0.684 | (20) | 0.692 | (22) | 0.720 | (20) | 0.721 | (23) | 0.710 | (23) | 0.726 | (24) | 0.724 | (24) | 0.747 | (24) | 0.746 | (24) |

| Nevada | 0.609 | (28) | 0.639 | (23) | 0.705 | (21) | 0.700 | (23) | 0.676 | (24) | 0.670 | (25) | 0.711 | (25) | 0.701 | (25) | 0.729 | (25) | 0.732 | (25) |

| New Hampshire | 0.678 | (21) | 0.698 | (19) | 0.712 | (19) | 0.789 | (17) | 0.822 | (13) | 0.791 | (17) | 0.790 | (17) | 0.867 | (12) | 0.891 | (12) | 0.872 | (12) |

| New Jersey | 0.769 | (15) | 0.768 | (17) | 0.765 | (18) | 0.802 | (14) | 0.803 | (17) | 0.781 | (18) | 0.783 | (18) | 0.780 | (17) | 0.813 | (17) | 0.808 | (18) |

| New Mexico | 0.395 | (47) | 0.428 | (45) | 0.417 | (46) | 0.431 | (46) | 0.438 | (45) | 0.475 | (44) | 0.477 | (45) | 0.496 | (45) | 0.499 | (45) | 0.552 | (42) |

| New York | 0.939 | (3) | 0.934 | (4) | 0.996 | (4) | 1.000 | (1) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.954 | (7) | 0.958 | (5) | 0.971 | (4) | 1.000 | (1) | 1.000 | (1) |

| Oregon | 0.876 | (8) | 0.898 | (7) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.990 | (5) | 0.934 | (7) | 0.981 | (3) | 1.000 | (1) | 1.000 | (1) | 1.000 | (1) | 1.000 | (1) |

| Pennsylvania | 0.533 | (36) | 0.530 | (37) | 0.546 | (37) | 0.560 | (35) | 0.566 | (34) | 0.583 | (33) | 0.613 | (34) | 0.635 | (33) | 0.642 | (32) | 0.656 | (30) |

| Rhode Island | 0.812 | (11) | 0.818 | (10) | 0.824 | (11) | 0.858 | (9) | 0.893 | (8) | 0.861 | (9) | 0.820 | (15) | 0.943 | (7) | 0.905 | (11) | 0.812 | (16) |

| Vermont | 0.930 | (4) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.975 | (5) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.963 | (4) | 0.966 | (6) | 0.891 | (8) | 0.934 | (8) | 0.940 | (10) | 0.945 | (6) |

| Virginia | 0.799 | (12) | 0.796 | (13) | 0.834 | (10) | 0.844 | (11) | 0.817 | (14) | 0.831 | (12) | 0.828 | (14) | 0.816 | (14) | 0.850 | (15) | 0.850 | (13) |

| Washington | 0.899 | (6) | 0.924 | (5) | 0.999 | (3) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.971 | (3) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.968 | (4) | 0.953 | (5) | 0.976 | (6) | 0.986 | (5) |

| Wisconsin | 0.630 | (24) | 0.631 | (25) | 0.639 | (27) | 0.671 | (25) | 0.635 | (26) | 0.654 | (26) | 0.650 | (29) | 0.673 | (28) | 0.663 | (28) | 0.674 | (28) |

| Avg. | 0.720 | (19) | 0.732 | (19) | 0.755 | (19) | 0.779 | (17) | 0.773 | (17) | 0.781 | (17) | 0.783 | (18) | 0.803 | (18) | 0.822 | (17) | 0.819 | (17) |

| Max. | 0.939 | (47) | 1.000 | (45) | 1.000 | (46) | 1.000 | (46) | 1.000 | (45) | 1.000 | (44) | 1.000 | (45) | 1.000 | (45) | 1.000 | (45) | 1.000 | (42) |

| Min. | 0.395 | (3) | 0.428 | (1) | 0.417 | (1) | 0.431 | (1) | 0.438 | (1) | 0.475 | (1) | 0.477 | (1) | 0.496 | (1) | 0.499 | (1) | 0.552 | (1) |

| S.D. | 0.141 | (11) | 0.147 | (11) | 0.158 | (12) | 0.159 | (12) | 0.153 | (11) | 0.149 | (11) | 0.138 | (11) | 0.138 | (11) | 0.142 | (12) | 0.131 | (11) |

| (b) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alabama | 0.493 | (41) | 0.479 | (42) | 0.486 | (42) | 0.507 | (40) | 0.528 | (40) | 0.528 | (41) | 0.532 | (42) | 0.556 | (39) | 0.580 | (36) | 0.579 | (38) |

| Alaska | 0.907 | (5) | 0.528 | (38) | 0.808 | (14) | 0.546 | (38) | 0.556 | (36) | 0.555 | (38) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.556 | (38) | 0.549 | (41) | 0.555 | (39) |

| Arkansas | 0.554 | (33) | 0.557 | (33) | 0.547 | (36) | 0.540 | (39) | 0.538 | (39) | 0.544 | (39) | 0.609 | (35) | 0.573 | (36) | 0.563 | (39) | 0.539 | (44) |

| Florida | 0.771 | (14) | 0.717 | (18) | 0.769 | (17) | 0.799 | (15) | 0.810 | (15) | 0.794 | (16) | 0.783 | (19) | 0.802 | (16) | 0.812 | (18) | 0.806 | (19) |

| Idaho | 1.000 | (1) | 1.000 | (1) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.999 | (4) | 0.956 | (5) | 0.976 | (5) | 0.932 | (7) | 0.932 | (10) | 0.949 | (9) | 0.944 | (7) |

| Indiana | 0.433 | (43) | 0.437 | (43) | 0.452 | (44) | 0.474 | (43) | 0.484 | (43) | 0.481 | (43) | 0.513 | (43) | 0.522 | (44) | 0.526 | (43) | 0.514 | (45) |

| Iowa | 0.540 | (35) | 0.535 | (35) | 0.555 | (35) | 0.572 | (33) | 0.594 | (32) | 0.602 | (31) | 0.633 | (30) | 0.667 | (29) | 0.661 | (29) | 0.639 | (33) |

| Kansas | 0.503 | (39) | 0.513 | (39) | 0.530 | (39) | 0.556 | (36) | 0.542 | (38) | 0.557 | (37) | 0.592 | (36) | 0.609 | (35) | 0.640 | (33) | 0.634 | (34) |

| Kentucky | 0.427 | (44) | 0.425 | (46) | 0.420 | (45) | 0.444 | (45) | 0.437 | (46) | 0.426 | (46) | 0.448 | (46) | 0.457 | (46) | 0.490 | (46) | 0.486 | (46) |

| Louisiana | 1.000 | (1) | 0.888 | (8) | 0.862 | (8) | 0.835 | (13) | 0.843 | (11) | 0.835 | (11) | 0.858 | (12) | 0.948 | (6) | 0.970 | (7) | 0.930 | (8) |

| Mississippi | 0.585 | (30) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.647 | (26) | 0.585 | (32) | 0.604 | (31) | 0.583 | (34) | 0.565 | (38) | 0.545 | (42) | 0.558 | (40) | 0.554 | (40) |

| Missouri | 0.493 | (40) | 0.498 | (40) | 0.487 | (41) | 0.502 | (41) | 0.501 | (42) | 0.516 | (42) | 0.537 | (41) | 0.551 | (41) | 0.525 | (44) | 0.552 | (41) |

| Montana | 0.412 | (46) | 0.379 | (47) | 0.412 | (47) | 0.425 | (47) | 0.420 | (47) | 0.416 | (47) | 0.419 | (47) | 0.437 | (47) | 0.452 | (47) | 0.469 | (47) |

| Nebraska | 0.550 | (34) | 0.571 | (32) | 0.556 | (34) | 0.570 | (34) | 0.555 | (37) | 0.572 | (35) | 0.583 | (37) | 0.615 | (34) | 0.629 | (35) | 0.602 | (35) |

| N. Carolina | 0.691 | (19) | 0.664 | (22) | 0.710 | (20) | 0.737 | (19) | 0.728 | (22) | 0.730 | (20) | 0.765 | (20) | 0.771 | (18) | 0.791 | (19) | 0.802 | (20) |

| N. Dakota | 0.291 | (49) | 0.314 | (48) | 0.337 | (48) | 0.347 | (48) | 0.360 | (48) | 0.378 | (48) | 0.370 | (48) | 0.373 | (48) | 0.390 | (48) | 0.393 | (48) |

| Ohio | 0.531 | (38) | 0.532 | (36) | 0.558 | (33) | 0.591 | (31) | 0.573 | (33) | 0.588 | (32) | 0.625 | (32) | 0.637 | (32) | 0.639 | (34) | 0.653 | (31) |

| Oklahoma | 0.461 | (42) | 0.487 | (41) | 0.488 | (40) | 0.497 | (42) | 0.522 | (41) | 0.539 | (40) | 0.538 | (40) | 0.555 | (40) | 0.579 | (37) | 0.579 | (37) |

| S. Carolina | 0.624 | (25) | 0.633 | (24) | 0.656 | (25) | 0.695 | (24) | 0.742 | (19) | 0.723 | (21) | 0.744 | (23) | 0.757 | (20) | 0.781 | (21) | 0.759 | (23) |

| S. Dakota | 0.764 | (16) | 0.774 | (15) | 0.817 | (12) | 0.791 | (16) | 0.807 | (16) | 0.815 | (14) | 0.866 | (11) | 0.833 | (13) | 0.851 | (14) | 0.834 | (15) |

| Tennessee | 0.678 | (20) | 0.677 | (21) | 0.688 | (23) | 0.708 | (22) | 0.734 | (20) | 0.721 | (22) | 0.746 | (22) | 0.738 | (23) | 0.759 | (23) | 0.810 | (17) |

| Texas | 0.532 | (37) | 0.538 | (34) | 0.540 | (38) | 0.549 | (37) | 0.556 | (35) | 0.560 | (36) | 0.562 | (39) | 0.569 | (37) | 0.573 | (38) | 0.593 | (36) |

| Utah | 0.422 | (45) | 0.436 | (44) | 0.453 | (43) | 0.473 | (44) | 0.460 | (44) | 0.464 | (45) | 0.482 | (44) | 0.527 | (43) | 0.543 | (42) | 0.547 | (43) |

| W. Virginia | 0.310 | (48) | 0.275 | (49) | 0.276 | (50) | 0.294 | (49) | 0.295 | (49) | 0.269 | (49) | 0.287 | (49) | 0.278 | (49) | 0.290 | (49) | 0.320 | (49) |

| Wyoming | 0.262 | (50) | 0.265 | (50) | 0.277 | (49) | 0.264 | (50) | 0.256 | (50) | 0.263 | (50) | 0.257 | (50) | 0.266 | (50) | 0.274 | (50) | 0.281 | (50) |

| Avg. | 0.594 | (30) | 0.591 | (31) | 0.599 | (31) | 0.597 | (32) | 0.602 | (32) | 0.604 | (32) | 0.639 | (31) | 0.632 | (32) | 0.644 | (32) | 0.642 | (32) |

| Max. | 1.000 | (49) | 1.000 | (48) | 1.000 | (48) | 0.999 | (48) | 0.956 | (48) | 0.976 | (48) | 1.000 | (48) | 0.948 | (48) | 0.970 | (48) | 0.944 | (48) |

| Min. | 0.291 | (1) | 0.314 | (1) | 0.337 | (1) | 0.347 | (4) | 0.360 | (5) | 0.378 | (5) | 0.370 | (1) | 0.373 | (6) | 0.390 | (7) | 0.393 | (7) |

| S.D. | 0.188 | (15) | 0.183 | (14) | 0.166 | (14) | 0.154 | (12) | 0.153 | (13) | 0.150 | (13) | 0.168 | (14) | 0.151 | (13) | 0.154 | (12) | 0.150 | (13) |

| UIM | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Arizona | 0.628 | (31) | 0.655 | (32) | 0.647 | (28) | 0.618 | (33) | 0.663 | (30) | 0.701 | (29) | 0.743 | (27) | 0.750 | (28) | 0.719 | (29) |

| California | 1.108 | (1) | 1.036 | (6) | 1.102 | (2) | 1.025 | (3) | 1.034 | (3) | 1.008 | (4) | 1.019 | (4) | 1.028 | (3) | 0.991 | (8) |

| Colorado | 0.646 | (29) | 0.662 | (31) | 0.637 | (30) | 0.637 | (31) | 0.654 | (32) | 0.665 | (32) | 0.683 | (32) | 0.693 | (34) | 0.681 | (31) |

| Connecticut | 1.055 | (5) | 1.023 | (7) | 1.021 | (6) | 0.952 | (11) | 0.964 | (10) | 0.966 | (8) | 1.023 | (3) | 1.018 | (5) | 0.918 | (11) |

| Delaware | 1.005 | (7) | 0.880 | (13) | 0.803 | (16) | 0.825 | (19) | 0.891 | (13) | 0.861 | (16) | 0.814 | (20) | 0.846 | (20) | 0.855 | (17) |

| Georgia | 0.670 | (27) | 0.716 | (25) | 0.732 | (22) | 0.746 | (23) | 0.768 | (23) | 0.775 | (24) | 0.798 | (23) | 0.811 | (24) | 0.815 | (22) |

| Hawaii | 0.807 | (17) | 0.763 | (22) | 0.740 | (20) | 0.707 | (27) | 0.830 | (19) | 0.795 | (22) | 0.811 | (21) | 0.828 | (23) | 0.787 | (24) |

| Illinois | 0.683 | (26) | 0.688 | (28) | 0.683 | (27) | 0.653 | (30) | 0.673 | (29) | 0.699 | (30) | 0.739 | (28) | 0.747 | (29) | 0.728 | (28) |

| Maine | 0.833 | (15) | 0.842 | (17) | 0.854 | (14) | 0.851 | (15) | 0.900 | (12) | 0.863 | (15) | 0.871 | (14) | 0.908 | (16) | 0.935 | (10) |

| Maryland | 0.880 | (12) | 0.910 | (11) | 0.909 | (10) | 0.920 | (12) | 0.909 | (11) | 0.940 | (10) | 0.957 | (11) | 1.017 | (7) | 0.917 | (12) |

| Massachusetts | 1.082 | (2) | 1.078 | (2) | 1.156 | (1) | 1.122 | (1) | 1.133 | (2) | 1.015 | (3) | 1.034 | (2) | 1.106 | (1) | 1.030 | (1) |

| Michigan | 0.636 | (30) | 0.663 | (30) | 0.642 | (29) | 0.629 | (32) | 0.661 | (31) | 0.643 | (35) | 0.694 | (31) | 0.700 | (32) | 0.675 | (32) |

| Minnesota | 0.752 | (19) | 0.753 | (23) | 0.738 | (21) | 0.731 | (26) | 0.743 | (26) | 0.750 | (27) | 0.763 | (25) | 0.794 | (26) | 0.774 | (25) |

| Nevada | 0.720 | (23) | 0.768 | (21) | 0.727 | (23) | 0.702 | (28) | 0.705 | (28) | 0.744 | (28) | 0.748 | (26) | 0.768 | (27) | 0.748 | (27) |

| New Hampshire | 0.822 | (16) | 0.792 | (19) | 0.828 | (15) | 0.847 | (16) | 0.834 | (18) | 0.828 | (19) | 0.919 | (12) | 0.932 | (11) | 0.894 | (13) |

| New Jersey | 0.863 | (14) | 0.850 | (14) | 0.857 | (13) | 0.843 | (17) | 0.827 | (20) | 0.827 | (20) | 0.824 | (18) | 0.853 | (19) | 0.820 | (20) |

| New Mexico | 0.480 | (44) | 0.458 | (45) | 0.449 | (45) | 0.459 | (46) | 0.519 | (43) | 0.503 | (45) | 0.526 | (45) | 0.524 | (46) | 0.565 | (43) |

| New York | 1.062 | (3) | 1.087 | (1) | 1.051 | (4) | 1.019 | (4) | 1.001 | (8) | 1.037 | (2) | 1.053 | (1) | 1.067 | (2) | 1.001 | (5) |

| Oregon | 0.999 | (8) | 1.061 | (4) | 1.015 | (8) | 0.954 | (10) | 1.017 | (5) | 1.042 | (1) | 0.974 | (8) | 0.925 | (13) | 1.001 | (4) |

| Pennsylvania | 0.596 | (34) | 0.610 | (33) | 0.595 | (32) | 0.589 | (35) | 0.617 | (36) | 0.639 | (36) | 0.671 | (35) | 0.680 | (36) | 0.674 | (33) |

| Rhode Island | 0.998 | (9) | 0.922 | (10) | 0.881 | (11) | 0.909 | (13) | 0.990 | (9) | 0.886 | (14) | 0.991 | (6) | 0.927 | (12) | 0.817 | (21) |

| Vermont | 1.039 | (6) | 1.038 | (5) | 1.044 | (5) | 0.983 | (7) | 1.002 | (6) | 0.991 | (5) | 0.959 | (10) | 0.948 | (10) | 0.969 | (9) |

| Virginia | 0.867 | (13) | 0.907 | (12) | 0.870 | (12) | 0.835 | (18) | 0.874 | (14) | 0.857 | (17) | 0.860 | (15) | 0.898 | (17) | 0.874 | (15) |

| Washington | 1.058 | (4) | 1.069 | (3) | 1.052 | (3) | 1.056 | (2) | 1.138 | (1) | 0.987 | (6) | 0.988 | (7) | 1.026 | (4) | 1.011 | (2) |

| Wisconsin | 0.698 | (25) | 0.702 | (27) | 0.701 | (25) | 0.667 | (29) | 0.713 | (27) | 0.688 | (31) | 0.717 | (29) | 0.702 | (31) | 0.695 | (30) |

| Avg. | 0.839 | (17) | 0.837 | (18) | 0.829 | (17) | 0.811 | (20) | 0.842 | (18) | 0.828 | (19) | 0.847 | (18) | 0.860 | (19) | 0.836 | (19) |

| Max. | 1.108 | (44) | 1.087 | (45) | 1.156 | (45) | 1.122 | (46) | 1.138 | (43) | 1.042 | (45) | 1.053 | (45) | 1.106 | (46) | 1.030 | (43) |

| Min. | 0.480 | (1) | 0.458 | (1) | 0.449 | (1) | 0.459 | (1) | 0.519 | (1) | 0.503 | (1) | 0.526 | (1) | 0.524 | (1) | 0.565 | (1) |

| S.D. | 0.183 | (12) | 0.173 | (12) | 0.181 | (11) | 0.170 | (12) | 0.168 | (12) | 0.147 | (12) | 0.140 | (12) | 0.144 | (12) | 0.129 | (11) |

| (b) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alabama | 0.496 | (42) | 0.511 | (42) | 0.509 | (41) | 0.530 | (41) | 0.554 | (41) | 0.547 | (42) | 0.597 | (40) | 0.624 | (39) | 0.609 | (39) |

| Alaska | 0.543 | (40) | 0.849 | (15) | 0.552 | (38) | 1.000 | (5) | 0.872 | (15) | 0.924 | (11) | 0.854 | (17) | 0.922 | (14) | 1.007 | (3) |

| Arkansas | 0.602 | (32) | 0.578 | (37) | 0.549 | (39) | 0.560 | (37) | 0.632 | (34) | 0.777 | (23) | 0.612 | (38) | 0.696 | (33) | 0.566 | (42) |

| Florida | 0.746 | (20) | 0.821 | (18) | 0.803 | (16) | 0.810 | (21) | 0.839 | (17) | 0.833 | (18) | 0.857 | (16) | 0.859 | (18) | 0.871 | (16) |

| Idaho | 0.910 | (10) | 1.016 | (8) | 1.016 | (7) | 0.959 | (9) | 1.031 | (4) | 0.956 | (9) | 1.000 | (5) | 1.018 | (6) | 0.993 | (7) |

| Indiana | 0.460 | (45) | 0.480 | (44) | 0.477 | (44) | 0.486 | (44) | 0.505 | (44) | 0.528 | (43) | 0.557 | (44) | 0.563 | (43) | 0.537 | (45) |

| Iowa | 0.555 | (37) | 0.583 | (36) | 0.575 | (34) | 0.597 | (34) | 0.632 | (33) | 0.651 | (33) | 0.714 | (30) | 0.710 | (30) | 0.672 | (35) |

| Kansas | 0.549 | (38) | 0.571 | (39) | 0.562 | (36) | 0.547 | (40) | 0.585 | (39) | 0.610 | (37) | 0.647 | (37) | 0.683 | (35) | 0.659 | (36) |

| Kentucky | 0.437 | (47) | 0.440 | (46) | 0.446 | (46) | 0.439 | (47) | 0.449 | (46) | 0.467 | (46) | 0.492 | (46) | 0.525 | (45) | 0.510 | (46) |

| Louisiana | 0.888 | (11) | 0.968 | (9) | 0.975 | (9) | 0.985 | (6) | 1.002 | (7) | 0.977 | (7) | 0.965 | (9) | 1.011 | (8) | 0.998 | (6) |

| Mississippi | 0.740 | (21) | 0.715 | (26) | 0.591 | (33) | 0.882 | (14) | 0.783 | (21) | 0.897 | (12) | 0.674 | (33) | 0.997 | (9) | 0.759 | (26) |

| Missouri | 0.547 | (39) | 0.535 | (40) | 0.523 | (40) | 0.514 | (43) | 0.544 | (42) | 0.557 | (40) | 0.582 | (42) | 0.557 | (44) | 0.570 | (41) |

| Montana | 0.399 | (48) | 0.439 | (47) | 0.428 | (47) | 0.422 | (48) | 0.438 | (47) | 0.431 | (47) | 0.467 | (47) | 0.485 | (47) | 0.491 | (47) |

| Nebraska | 0.599 | (33) | 0.593 | (35) | 0.573 | (35) | 0.559 | (39) | 0.600 | (37) | 0.600 | (38) | 0.655 | (36) | 0.673 | (38) | 0.628 | (37) |

| N. Carolina | 0.728 | (22) | 0.776 | (20) | 0.767 | (19) | 0.754 | (22) | 0.772 | (22) | 0.803 | (21) | 0.822 | (19) | 0.838 | (21) | 0.824 | (19) |

| N. Dakota | 0.321 | (49) | 0.350 | (48) | 0.349 | (48) | 0.362 | (49) | 0.398 | (48) | 0.381 | (48) | 0.402 | (48) | 0.422 | (48) | 0.417 | (48) |

| Ohio | 0.578 | (35) | 0.608 | (34) | 0.606 | (31) | 0.584 | (36) | 0.618 | (35) | 0.644 | (34) | 0.673 | (34) | 0.679 | (37) | 0.674 | (34) |

| Oklahoma | 0.509 | (41) | 0.518 | (41) | 0.500 | (43) | 0.526 | (42) | 0.566 | (40) | 0.553 | (41) | 0.595 | (41) | 0.622 | (40) | 0.609 | (40) |

| S. Carolina | 0.653 | (28) | 0.686 | (29) | 0.698 | (26) | 0.746 | (24) | 0.758 | (24) | 0.765 | (26) | 0.809 | (22) | 0.836 | (22) | 0.795 | (23) |

| S. Dakota | 0.787 | (18) | 0.846 | (16) | 0.795 | (18) | 0.810 | (20) | 0.854 | (16) | 0.889 | (13) | 0.892 | (13) | 0.913 | (15) | 0.876 | (14) |

| Tennessee | 0.708 | (24) | 0.729 | (24) | 0.711 | (24) | 0.738 | (25) | 0.756 | (25) | 0.768 | (25) | 0.784 | (24) | 0.809 | (25) | 0.845 | (18) |

| Texas | 0.566 | (36) | 0.575 | (38) | 0.552 | (37) | 0.559 | (38) | 0.588 | (38) | 0.579 | (39) | 0.608 | (39) | 0.614 | (41) | 0.621 | (38) |

| Utah | 0.495 | (43) | 0.508 | (43) | 0.501 | (42) | 0.479 | (45) | 0.494 | (45) | 0.509 | (44) | 0.559 | (43) | 0.574 | (42) | 0.557 | (44) |

| W. Virginia | 0.451 | (46) | 0.305 | (49) | 0.295 | (49) | 0.980 | (8) | 0.294 | (49) | 0.300 | (49) | 0.298 | (50) | 0.308 | (50) | 0.338 | (50) |

| Wyoming | 0.270 | (50) | 0.286 | (50) | 0.265 | (50) | 0.291 | (50) | 0.279 | (50) | 0.264 | (50) | 0.298 | (49) | 0.337 | (49) | 0.343 | (49) |

| Avg. | 0.601 | (33) | 0.639 | (32) | 0.611 | (33) | 0.646 | (32) | 0.664 | (31) | 0.680 | (30) | 0.688 | (31) | 0.723 | (30) | 0.700 | (31) |

| Max. | 0.910 | (49) | 1.016 | (48) | 1.016 | (48) | 1.000 | (49) | 1.031 | (48) | 0.977 | (48) | 1.000 | (48) | 1.018 | (48) | 1.007 | (48) |

| Min. | 0.321 | (10) | 0.350 | (8) | 0.349 | (7) | 0.362 | (5) | 0.398 | (4) | 0.381 | (7) | 0.402 | (5) | 0.422 | (6) | 0.417 | (3) |

| S.D. | 0.150 | (12) | 0.175 | (12) | 0.167 | (12) | 0.189 | (14) | 0.176 | (13) | 0.178 | (14) | 0.160 | (13) | 0.175 | (14) | 0.172 | (14) |

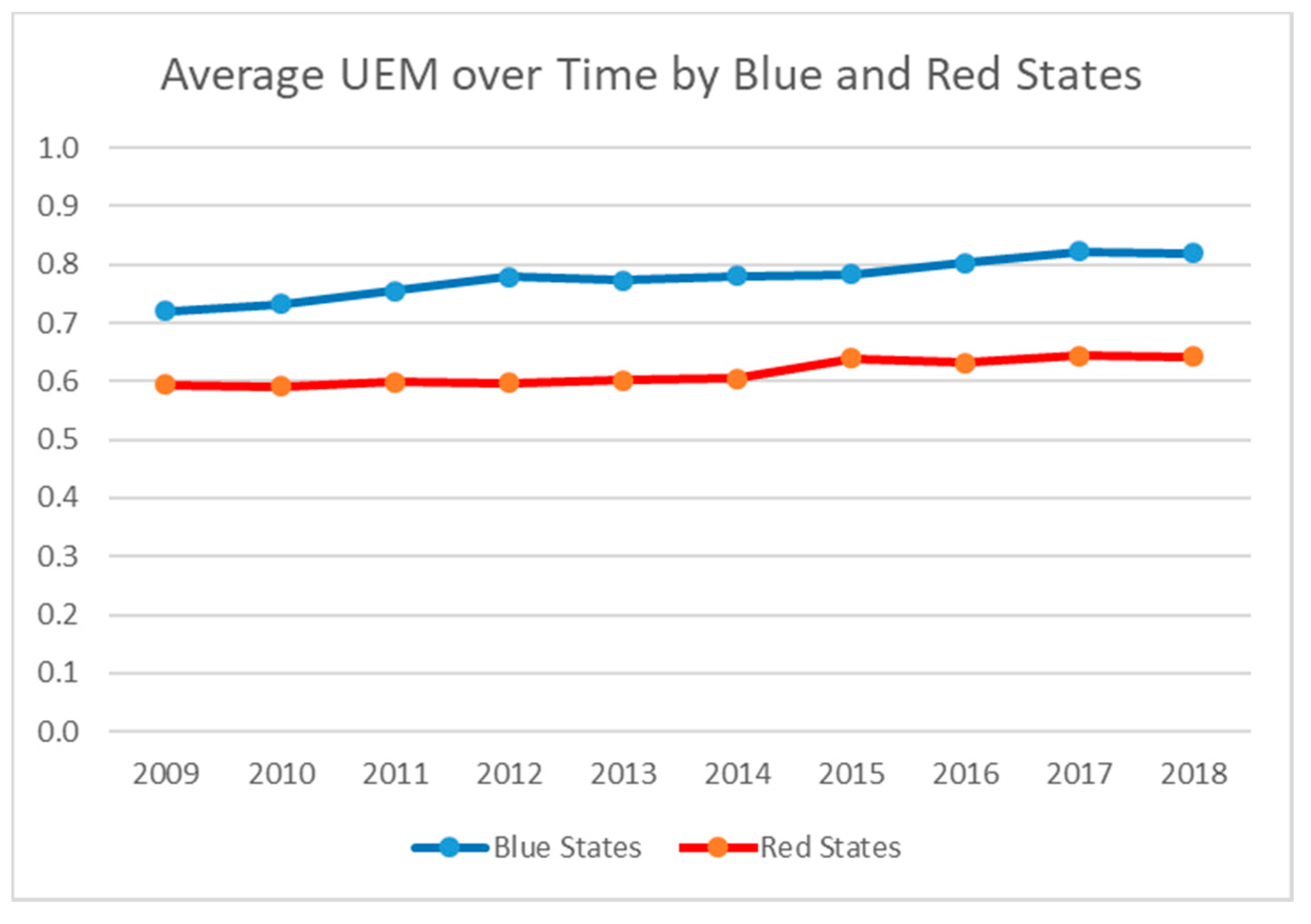

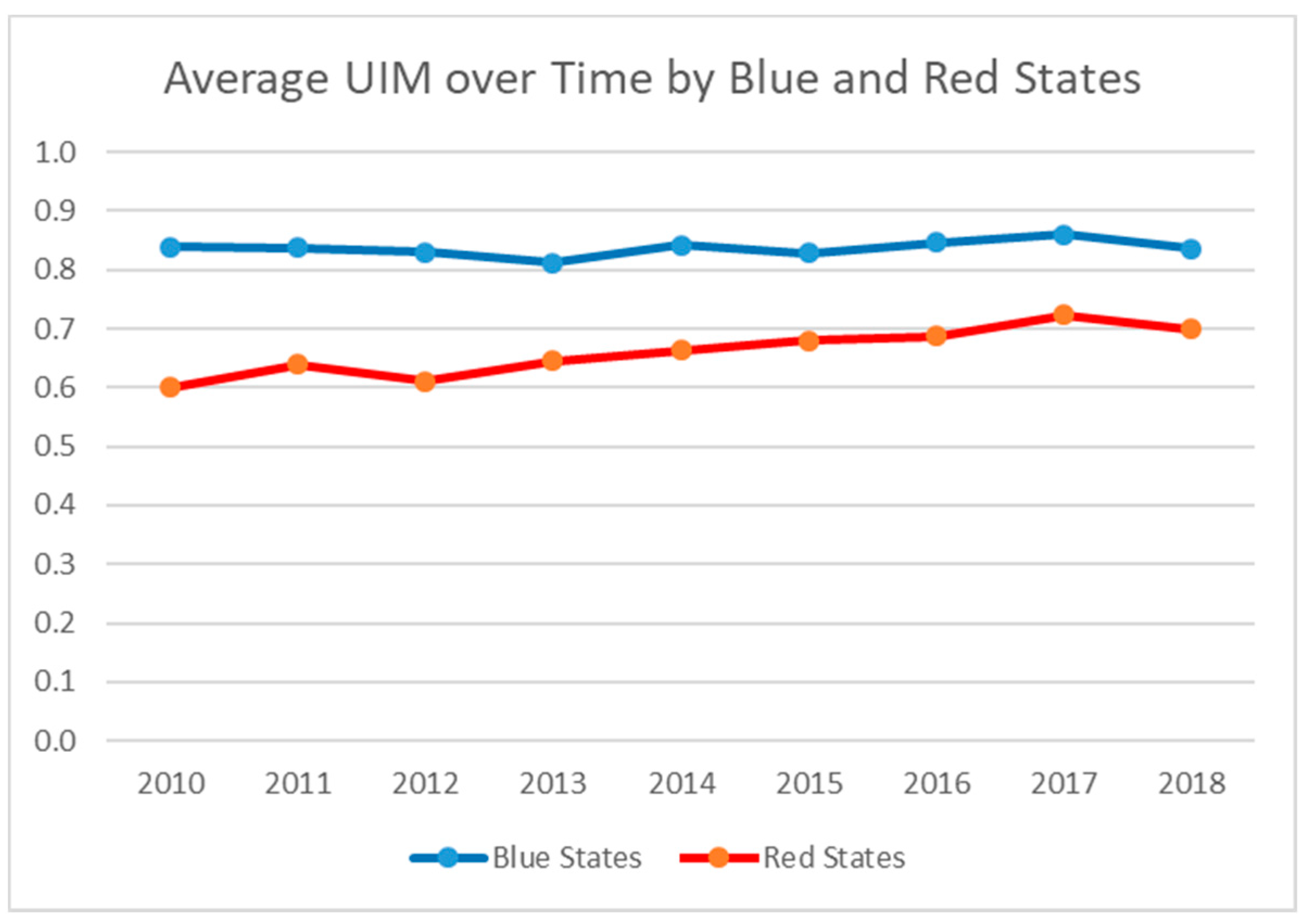

| Efficiency/Index | Mean (Rank Sum) | χ2-Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D to D | D to R | R to R | ||

| UEM | 0.816 (70,082) | 0.638 (16,747) | 0.586 (38,421) | 162.777 *** |

| UIM | 0.874 (56,885) | 0.672 (12,803) | 0.634 (31,787) | 146.295 *** |

| Efficiency/Index | Mean (Rank Sum) | χ2-Statistic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D to D | D to R | R to D | R to R | ||

| UEM | 0.695 (44,269) | 0.628 (24,458) | 0.817 (24,888) | 0.660 (31,635) | 54.365 *** |

| UIM | 0.742 (35,251) | 0.671 (19,723) | 0.887 (20,447) | 0.710 (26,055) | 51.119 *** |

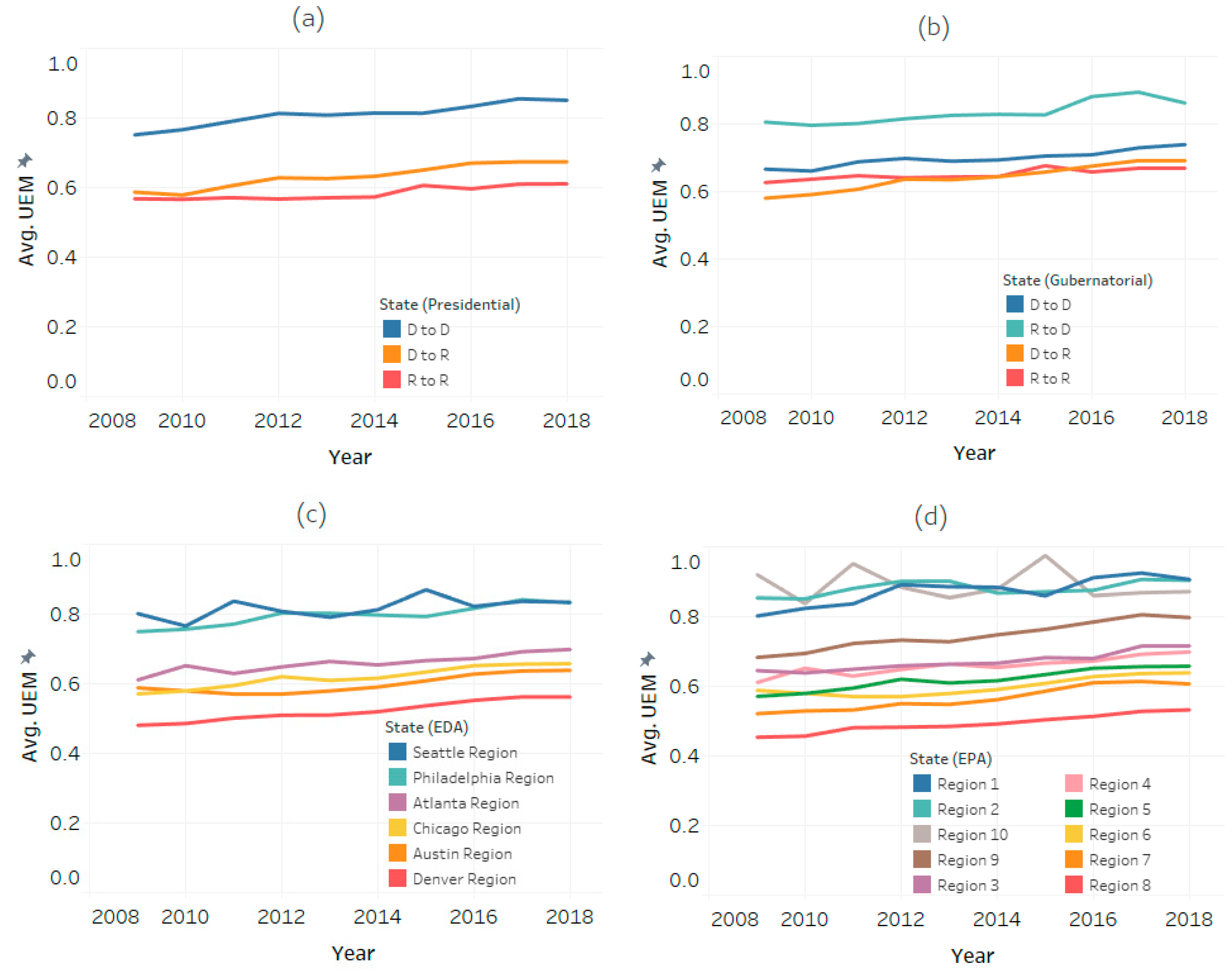

| Efficiency/Index | Mean (Rank Sum) | χ2-Statistic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlanta | Austin | Chicago | Denver | Philadelphia | Seattle | ||

| UEM | 0.664 (18,442) | 0.587 (14,492) | 0.625 (11,997) | 0.600 (19,154) | 0.802 (45,129) | 0.887 (16,036) | 161.557 *** |

| UIM | 0.711 (14,939) | 0.625 (11,437) | 0.659 (9112) | 0.639 (15,285) | 0.869 (37,221) | 0.966 (13,482) | 168.804 *** |

| Efficiency/Index | Mean (Rank Sum) | χ2-Statistic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | Region 2 | Region 3 | Region 4 | Region 5 | Region 6 | Region 7 | Region 8 | Region 9 | Region 10 | ||

| UEM | 0.880 (24,095) | 0.884 (8041) | 0.674 (12,993) | 0.664 (18,442) | 0.625 (11,997) | 0.600 (8629) | 0.571 (5863) | 0.497 (7107) | 0.753 (12,047) | 0.887 (16,036) | 230.318 *** |

| UIM | 0.955 (19,904) | 0.941 (6516) | 0.738 (10,801) | 0.711 (14,939) | 0.659 (9112) | 0.646 (7045) | 0.598 (4392) | 0.525 (5474) | 0.810 (9811) | 0.966 (13,482) | 234.047 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sueyoshi, T.; Ryu, Y. Environmental Assessment and Sustainable Development in the United States. Energies 2021, 14, 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14041180

Sueyoshi T, Ryu Y. Environmental Assessment and Sustainable Development in the United States. Energies. 2021; 14(4):1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14041180

Chicago/Turabian StyleSueyoshi, Toshiyuki, and Youngbok Ryu. 2021. "Environmental Assessment and Sustainable Development in the United States" Energies 14, no. 4: 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14041180

APA StyleSueyoshi, T., & Ryu, Y. (2021). Environmental Assessment and Sustainable Development in the United States. Energies, 14(4), 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14041180