Contradictory Conservation: The Role of Leadership in Shaping Energy Efficiency Culture in Urban Residential Cooperative Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Leadership and Organizational Culture

1.2. The Importance of Building Type

1.3. Social Norms for Energy Efficiency

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analytical Approach

2.2. Site and Site Selection

2.3. Methodology

2.4. Participants

3. Results

3.1. A Decentralized and Transparent Building

“Whoever. If you notice it, you can buy it. You just submit your receipt and get reimbursed. Or you can tell the super. He has an account at Home Depot for our building.”

3.2. Energy and Environmental Findings

“We couldn’t control the heat. All we could do was turn the radiators off. Now we have staggered sensors at opposite ends of the building. Our system is so old. We have all been so much happier.”

“We’ve been taking small steps to make the building more energy efficient. I’d rank us like a 6 or a 7 on how important it is to conserve in the building. The building composts. We use it to fertilize the garden. Everyone puts their stuff in it. We buy green (cleaning products).”

3.3. A Culture of Cost-Efficiency

“Myself and three other people were the sponsors of the conversion to co-op. Of those 4, one died, and another walked away from his interest. This was in about 1990 when the real estate market was in really poor shape. Since he left, the management fell to me. And I’ve been involved in varying degrees since then. There were 3 owner-occupants when I got involved in the building. Five of the 16 apartments had been sold. And the owner occupants, with the exception of one person, were not active in the building. So, the management of it, since we owned 11 apartments, by default the management fell to me.”

“He sets what are seemingly arbitrary rules. But people know that if he leaves it would be so much harder.”

“I think it’s a very family-friendly building, all of the apartments in the back have 2 bedrooms, so people can start families here, but then they move out. If we had a kid, we couldn’t be here very long.”

“The situation is that it’s most people’s first purchase, so you know, kids come along, kids get bigger, then they’re looking for a bigger place. But, you know, it tends to be people of a similar outlook, and they’re interested in the wellbeing of the building and keeping costs down. Hopefully there’s some carryover (on the board) and you get more people like (Resident).”

“This sounds a little bizarre,” he explained, “but at the time it was a good decision. We’ve subsequently converted to duel fuel, and we’ve been running it on gas. The price of gas has dropped tremendously. The ability to switch fuels has been huge.” He also explained that the building maintained a separate hot water heater, “but because of the boiler that was running anyway, we got almost free hot water in the winter.”

“The motivation was not environmental. It was to reduce costs and increase comfort. Some people may look at it from an environmental perspective. But that wasn’t my goal.”

“Well, there hasn’t really been any material change except the price has gone up. I haven’t really seen any change in usage. At some point we replaced the light fixtures, and we tried to use more energy efficient lighting.”

“Hmm. If that’s true, it’s that co-op people expect that they will pay for things. They recognize that they are paying for things. When people aren’t paying for something they use more of it. Perhaps people in co-ops are more cost conscious. But, a properly run rental building will have a cost conscious landlord too. But I guess a co-op board would be more sensitive to things. You can have an increase in the maintenance charge when the heat is going up 10% or 15%. A few years ago we had a fuel assessment. It got everybody’s attention. It made everyone ask what are we doing about it.”

3.4. Interview Summary

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

- Less than one year

- 1–2 years

- 3–4 years

- 5 years or more

- Never

- Sometimes

- Often

- Every day

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know them at all

- I know them a little

- I know them very well

- Strongly agree (I am entirely aware of all decisions made by the board)

- Agree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree (I am not at all aware of decisions that are made by the board)

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

- Strongly agree (my opinion matters very much and is taken into account when the building makes decisions)

- Agree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree (my opinion does not matter at all and plays no role in any decision-making in the building)

- I would like more input

- I would like less input

- I am satisfied with my current amount of input

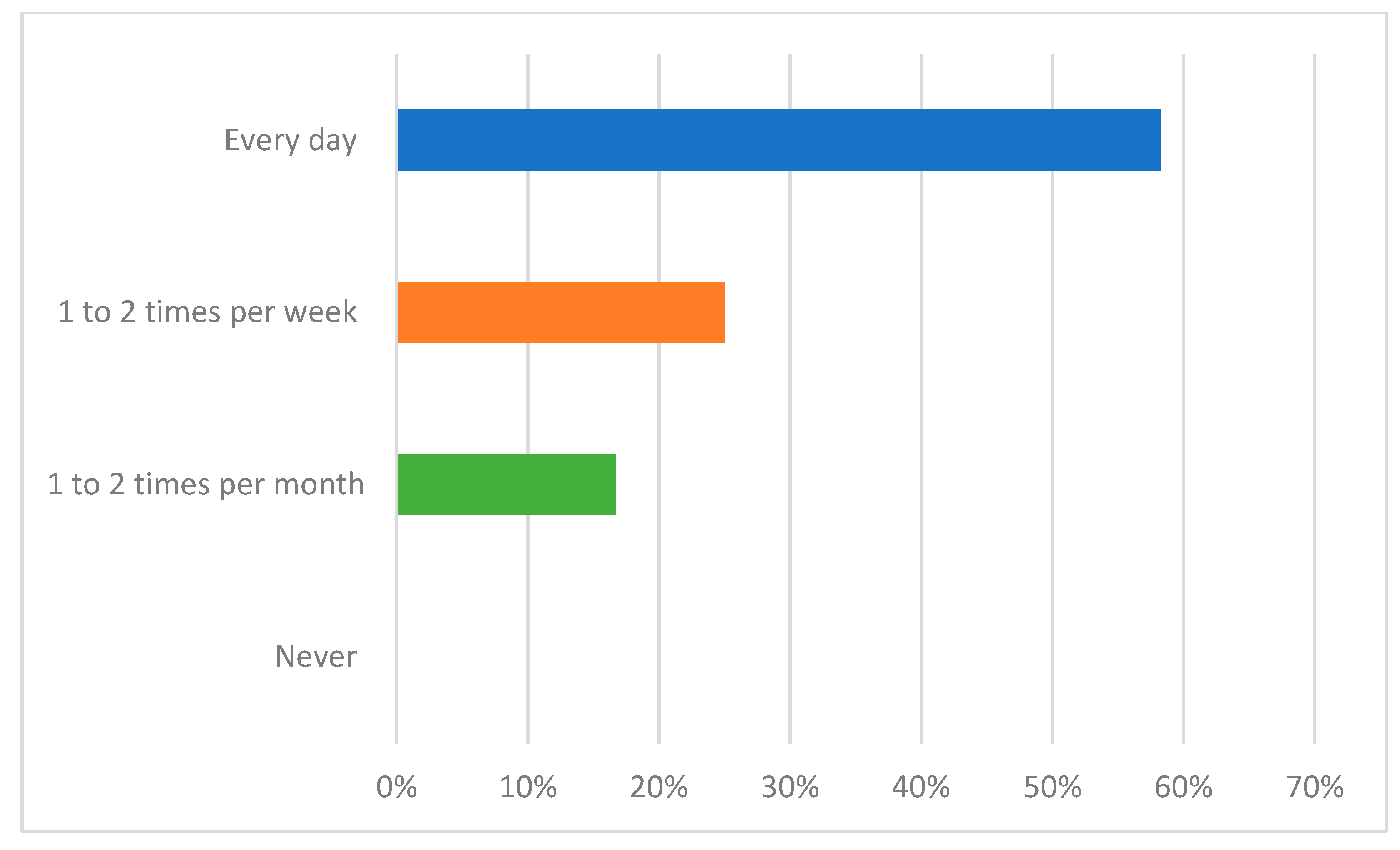

- Every day

- A few times a week

- Once a week

- Once a month

- Rarely/Never

- To save money on my monthly electric bill

- To set a good example for my family, children, or other people I live with

- To avoid being wasteful

- To do my part to help lessen energy consumption in my building

- Other (please specify) _________________________________________

- Yes

- No

- Don’t know

- Sharing information (emails, flyers up in mail room, etc.)

- Training programs

- Special events for residents (composting, efficient light bulb giveaways)

- Financial incentives or penalty (a rebate or a common area electricity/water charge that all residents must pay)

- Other (please describe)__________________________________________

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

- I do not care at all

- I care a little

- I care a lot

- 18–25

- 26–30

- 30–39

- 40–49

- 50–59

- 60–69

- Over 70

- Very liberal

- Somewhat liberal

- Moderate

- Somewhat conservative

- Very conservative

- High school

- Some college

- Associates degree

- Bachelors degree

- Graduate school—Masters degree, MBA, JD, PhD or MD

- Under $25,000/year

- $25,000–$49,999/year

- $50,000–$74,999/year

- $75,000–$99,999/year

- $100,000–$149,999/year

- $150,000–$199,999/year

- Over $200,000/year

- Male

- Female

- 1 person

- 2 people

- 3 people

- 4 people

- 5 or more people

- Studio

- 1 bedroom

- 2 bedroom

- 3 bedroom

- Other (please describe) __________________________________________________

References

- Prindle, W.; Finlinson, S. How organizations can drive behavior-based energy efficiency. In Energy, Sustainability and the Environment; Technology, Incentives and Behavior; Sioshansi, F.P., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 305–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, E. Organizational characteristics in residential rental buildings: Exploring the role of centralization in energy outcomes. In Handbook of Sustainability and Social Science Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schelly, C.; Cross, J.E.; Franzen, W.S.; Hall, P.; Reeve, S. Reducing Energy Consumption and Creating a Conservation Culture in Organizations: A Case Study of One Public School District. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 316–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization, Revised&Updated ed.; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- de Teixeira, E.O.; Werther, W.B. Resilience: Continuous renewal of competitive advantages. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. Understanding and Managing Organizational Behavior, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H. Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, 1st ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Axon, C.J.; Bright, S.J.; Dixon, T.J.; Janda, K.B.; Kolokotroni, M. Building communities: Reducing energy use in tenanted commercial property. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, K.B. Building communities and social potential: Between and beyond organizations and individuals in commercial properties. Energy Policy 2014, 67, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T. The Hidden Dimension; Anchor: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Deline, M.B. Energizing organizational research: Advancing the energy field with group concepts and theories. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 8, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinkhuyzen, O.M.; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S.I. The role of moral leadership for sustainable production and consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselink, R.; Blok, V.; Ringersma, J. Pro-environmental behaviour in the workplace and the role of managers and organisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkland, T.A. An Introduction to the Policy Process: Theories, Concepts, and Models of Public Policy Making, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hermwille, L. The role of narratives in socio-technical transitions—Fukushima and the energy regimes of Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havermans, L.A.; Keegan, A.; den Hartog, D.N. Choosing your words carefully: Leaders’ narratives of complex emergent problem resolution. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlow, A.; Mills, J.H. Telling tales out of school: Sensemaking and narratives of legitimacy in an organizational change process. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnington, A.; Alshamsi, A.; Karatas-Ozkan, M.; Nicolopoulou, K.; Ozbilgin, M.; Tatli, A.; Vassilopoulou, J. Early Organizational Diffusion of Contemporary Policies: Narratives of Sustainability and Talent Management. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Low, S. A multi-disciplinary framework for the study of private housing schemes: Integrating anthropological, psychological and political levels of theory and analysis. GeoJournal 2012, 77, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.; Donovan, G.T.; Gieseking, J. Shoestring democracy: Gated condominiums and market-rate cooperatives in new york. J. Urban Aff. 2012, 34, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, G.; Walks, A. Rising cities: Condominium development and the private transformation of the metropolis. Geoforum 2013, 49, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, H. Condominium and Cooperative Housing: Transactional Efficiency, Tax Subsidies, and Tenure Choice. J. Leg. Stud. 1991, 20, 25–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, E.L.; Andrews, C.J.; Senick, J.A.; Wener, R.E.; Krogmann, U.; Allacci, M.S. Distinguishing between green building occupants’ reasoned and unplanned behaviours. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khansari, N.; Hewitt, E. Incorporating an agent-based decision tool to better understand occupant pathways to GHG reductions in NYC buildings. Cities 2020, 97, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Pub (Sd): Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kleindorfer, P.R.; Kunreuther, H.G.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Decision Sciences: An Integrative Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H. Social norms and energy conservation. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OPower. OPower Results. Available online: http://opower.com/results (accessed on 1 November 2014).

- Dupré, M.; Meineri, S. Increasing recycling through displaying feedback and social comparative feedback. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Horen, F.; van der Wal, A.; Grinstein, A. Green, greener, greenest: Can competition increase sustainable behavior? J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 59, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.; Babbie, E.R. Essential Research Methods for Social Work, 2nd ed.; Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.B. Designing Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, R.M. (Ed.) Survey Methodology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P. Changing Behavior in Households and Communities: What Have We Learned? In New Tools for Environmental Protection: Education, Information, and Voluntary Measures; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Are There Universal Aspects in the Structure and Contents of Human Values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M.; Welcomer, S.; Scherer, R.F.; Pradenas, L.; Parada, V. A Cross-Cultural Assessment of Three Theories of Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Comparison Between Business Students of Chile and the United States. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 634–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M. The Edge and the Center: Gated Communities and the Discourse of Urban Fear. Am. Anthropol. 2001, 103, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither Agree or Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have formed a strong friendship with at least one person in the building | 41.7% (5) | 41.7% (5) | 0.0% (0) | 8.3% (1) | 8.3% (1) |

| I have formed casual acquaintances with many people in the building | 58.3% (7) | 41.7% (5) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) |

| My building encourages me to get to know my neighbors through social activities, shared spaces, projects in the building, and other on-site activities | 33.3% (4) | 33.3% (4) | 8.3% (1) | 25.0% (3) | 0.0% (0) |

| I feel a sense of connection and belonging in my building | 50.0% (6) | 25.0% (3) | 0.0% (0) | 16.7% (2) | 8.3% (1) |

| I am aware of discussions that are made for/about my building by the co-op board | 41.7% (5) | 33.3% (4) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 25.0% (3) |

| I am included in the decision-making of the building | 16.7% (2) | 16.7% (2) | 16.7% (2) | 25.0% (3) | 25.0% (3) |

| My opinion matters in the decision-making of the building | 16.7% (2) | 41.7% (5) | 16.7% (2) | 8.3% (1) | 16.7% (2) |

| Theme/Finding | Resident | Treasurer |

|---|---|---|

| Decentralized & Transparent Building |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| Energy and f Environmental Findings |

|

|

|

| |

| Culture of Cost- Efficiency (e.g., Treasurer’s leadership role in shaping building’s culture) |

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hewitt, E. Contradictory Conservation: The Role of Leadership in Shaping Energy Efficiency Culture in Urban Residential Cooperative Buildings. Energies 2021, 14, 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14030648

Hewitt E. Contradictory Conservation: The Role of Leadership in Shaping Energy Efficiency Culture in Urban Residential Cooperative Buildings. Energies. 2021; 14(3):648. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14030648

Chicago/Turabian StyleHewitt, Elizabeth. 2021. "Contradictory Conservation: The Role of Leadership in Shaping Energy Efficiency Culture in Urban Residential Cooperative Buildings" Energies 14, no. 3: 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14030648

APA StyleHewitt, E. (2021). Contradictory Conservation: The Role of Leadership in Shaping Energy Efficiency Culture in Urban Residential Cooperative Buildings. Energies, 14(3), 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14030648