Multiple Correspondence Analysis in the Study of Remuneration Fairness: Conclusions for Energy Companies—Case Study of Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Understanding the method of salary determining,

- Knowing how to increase salary,

- Performance-payment related mechanisms [11].

- Distributive justice—includes criteria that give a sense of receiving a fair outcome,

- Procedural justice—includes fair treatment during the decision-making process and implementation of decisions,

- Restorative justice—includes ways to deal with situations where established rules have been violated,

- Scope of justice—includes principles of opportunities within an organization.

2. Methods

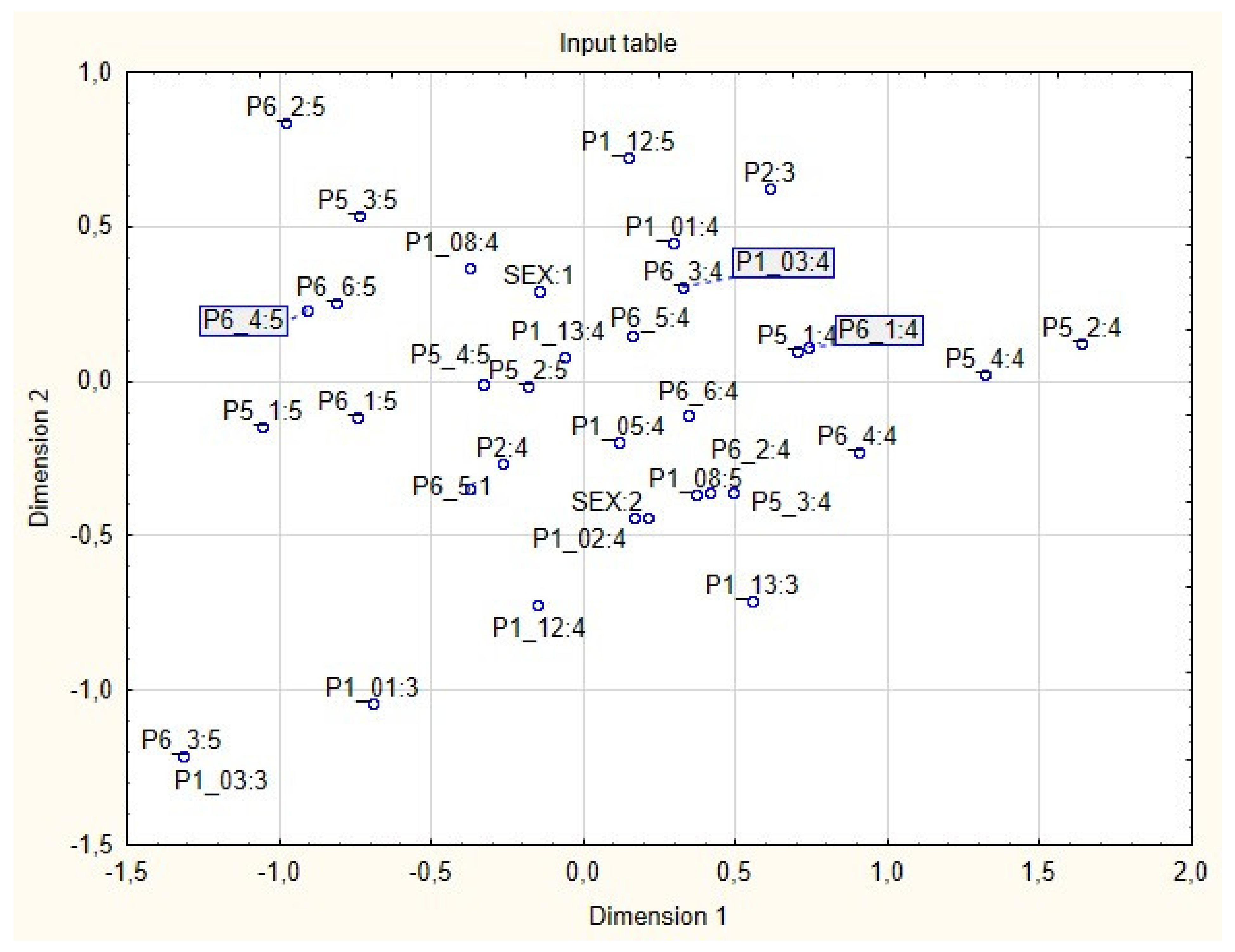

3. Empirical Results

4. Conclusions

- international comparative research in the area of salary management covering both employee opinions and applied systemic solutions in the area of financial and non-financial remuneration,

- interdisciplinary international research focused on such areas as, e.g., the impact of the applicable law on the development of remuneration systems and the impact of education systems on the remuneration expectations of employees in the sector,

- research for practical purposes—deepening the research taking into account the opinions of employees in sub-sectors, taking into account the views of employees depending on their positions, comparative research of remuneration solutions and methods of communicating remuneration in companies in the sector.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization. Yearbook of Labour Statistics 2019; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; pp. 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Słupik, S. Restructuring of employment in the energy sector in Poland. Sci. J. Univ. Econ. Katow. 2014, 283–291. Available online: https://www.ue.katowice.pl/fileadmin/_migrated/content_uploads/26_S.Slupik__Restrukturyzacja_zatrudnienia_w_sektorze....pdf (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- Energy Market Information Centre. Labour Market Barometer—Who Is Hiring in the Energy Industry Now? Available online: https://www.cire.pl/artykuly/serwis-informacyjny-cire-24/barometr-rynku-pracy---kto-teraz-zatrudnia-w-energetyce (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Raport Devire. Salary Overview Poland 2021. Energetyka Devire. 2021, pp. 16–17. Available online: https://www.devire.pl/publikacje/przeglad-wynagrodzen-2021/wynagrodzenia-w-energetyce/#elementor-action%3Aaction%3Dpopup%3Aopen%26settings%3DeyJpZCI6IjczMTYiLCJ0b2dnbGUiOmZhbHNlfQ%3D%3D (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Adams, J.S. Towards an understanding of inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V.H. Management and Motivation; Penguin: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F.I. Work and the Nature of Man; World Pub, Co.: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, D. The Human Side of Enterprise; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Lukow, P. Axiological foundations of fair wages. Educ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 49, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juchnowicz, M. The essence of fair remuneration in management—Theoretical and real aspects. Educ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 49, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enguix, L.P. The New EU Remuneration Policy as Good but Not Desired Corporate Governance Mechanism and the Role of CSR Disclosing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Social Charter of 18 October 1961. European Social Charter. 1999. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168006b642 (accessed on 23 April 2018).

- Labour Code Act of 26 June 1974 Journal of Laws 2019 Item 1040. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_isn=45181&p_lang=en (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Kulikowski, K. How is the amount of remuneration related to the evaluation of the fairness of remuneration and job satisfaction? Analysis based on the National Salary Survey 2015. Sci. J. Sil. Univ. Technol. 2017, 105, 227–240. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, F.D.; Kahn, L.M. The U.S. Gender Pay Gap in the 1990S: Slowing Convergence. ILR Rev. 2006, 60, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przychodzen, W.; Gomes-Bezares, F. CEO-employee pay gap: Productivity and value creation. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, R.; Jafta, R. Returns to Race: Labour Market Discrimination in Post-Apartheid South Africa; University of Stellenbosch, Department of Economics: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Keaveny, T.; Inderrieden, E.; Toumanoff, P. Gender differences in pay of young management professionals in the United States: A comprehensive view. J. Labor Res. 2007, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Breen, R.; Garsia-Penalosa, C. Learning and gender segregation. J. Labour Econ. 2002, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.R. The Effects of Motherhood Timing on Career Path. J. Popul. Econ. 2011, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, H.R.; Babcock, L.; Lai, L. Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: Sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 103, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinowska, H. Differentiation of fairness evaluation factors depending on gender. In Fair Remuneration of Employees from a Legal, Social and Managerial Perspective; Kimla-Walenda, K., Kostrzewa, A., Eds.; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, M.D.; de la Torre, M.M.V.; Rojas, R.H.; del Río, J.J. The Spanish Labor Market: A Gender Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierry, H.; de Jong, J.R. Job Evaluation. In Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology; Drenth, J.D., Thierry, H., de Wolff, C., Eds.; Psychology Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Juchnowicz, M.; Sienkiewicz, Ł. How to Evaluate Work? The Value of Position and Competence; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa, R.; Lafortune, G. The remuneration of general practitioners and specialists in 14 OECD countries: What are the factors influencing Variations across countries? OECD Health Work. Pap. 2008, 41. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/228632341330.pdf?expires=1637828659&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=FADADB272156FC40A0F724B05279DEAE (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Gupta, R. Salary and satisfaction: Private-public sectors in J&K. J. Indian Manag. 2011, 8, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Magnan, M.; Martin, D. Executive compensation and employee remuneration. The flexible principles of justice in pay. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, M.; Rernoningrum, H.; Ratieh, W. Remuneration, Motivation and Performance: Employee perspective. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics, Business and Economic Education, Semarang, Indonesia, 17–18 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Whitehead, D. How fair are wage practices along the supply chain? Global assessment in 2010–2011. In Proceedings of the Work Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 26–28 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowska, S. Effective Compensation Strategies—Creation and Application; Wolters Kluwer: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, N. Understanding Pay: Perceptions, Communication and Impact in For-Profit Organizations. Educ. Dr. Diss. Leadersh. 2015, 65, 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, T.; Fang, R.; Yang, Z. The impact of pay-for-performance perception and pay level satisfaction on employee work attitudes and extra-role behaviors: An investigation of moderating effects. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 8, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostkowski, T.; Wasilewski, J. Models of narratives about the justice of the remuneration system. Educ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 49, 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger, P.; Belogolovsky, E. The impact of pay secrecy on individual task performance. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 965–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkus, D. Under New Management: How Leading Organizations are Upending Business as Usual; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Elsesser, K. Pay Transparency is the Solution to the Pay Gap: Here’s One Company’s Success Story. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimelsesser/2018/09/05/pay-transparency-is-the-solutionto-the-pay-gap-heres-one-companys-success-story/#427e041e5010 (accessed on 5 September 2018).

- McLaren, S. Why These 3 Companies are Sharing What Their Employees Make. LinkedIn. Available online: https://business.linkedin.com/talent-solutions/blog/trends-and-research/2019/why-these-3-companies-aresharing-how-much-their-employees-make (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Towers-Clark, C. Why do Employers Keep Salaries Secret? Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/charlestowersclark/2018/11/15/why-doemployers-keep-salaries-secret/#6323b87f2f61 (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Day, N.E. An Investigation into Pay Communication: Is Ignorance Bliss? Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 739–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, N.E. Pay Equity as a Mediator of the Relationships among Attitudes and Communication about Pay Level Determination and Pay Secrecy. J. Lead. Organ. Stud. 2012, 19, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futrell, C.M.; Jenkins, O.C. Pay Secrecy Versus Pay Disclosure for Salesmen: A Longitudinal Study. J. Mark. Res. 1978, 15, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherson, D.J. Getting the Pay Thing Right. Workspan 2000, 43, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K.D.; McMullen, T. Rewards Next Practices: 2013 and beyond. WorldatWork J. 2013, 22, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, L.; Gely, R. Love, Sex and Politics? Sure. Salary? ‘No way’: Workplace Social Norms and the Law. Berkeley J. Law Employ. 2004, 25, 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger, P.; Belogolovsky, E. The dark side of transparency: How and when pay administration practices affect employee helping. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Cable, D. The Dark Side of Transparency. McKinsey Quarterly. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/ourinsights/the-dark-side-of-transparency (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Zenger, T. The Case against Pay Transparency. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/09/the-case-against-pay-transparency (accessed on 1 October 2016).

- Friedman, D.S. Pay Transparency: The New Way of Doing Business. Compens. Benefits Rev. 2014, 46, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, S.; Devin, J. Pay Transparency: What Do Employees Think. WorldatWork J. 2018, 27, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Heisler, W. Increasing pay transparency: A guide for change. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 64, 73–81. Available online: https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0007681320301208?token=4D6DC6CBADC8D0663A37E53037D5AE385C76946460C373D1E740B761537E4D945B44DE8B5C1F3B0324796DF7B854495E&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20211124085542 (accessed on 17 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance. SSRN J. 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1787143 (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Kimla-Walenda, K.; Kostrzewa, A. (Eds.) Fair Remuneration of Employees from a Legal, Social and Managerial Perspective; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, H. Multivariate analysis. In Encyclopedia for Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Lewis-Beck, M., Bryman, A., Futing, T., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 699–702. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, H.; Valentin, D. Multiple correspondence analysis. In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics; Salkind, N.J., Ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 651–657. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J.; Valentin, D. Multiple factor analysis: Principal component analysis for multi-table and multi-block data sets. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2013, 5, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, M.J. Correspondence Analysis in Practice, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H.; Tomiuk, M.A.; Takane, Y. Correspondence analysis, multiple correspondence analysis and recent developments. In Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology; Millsap, R., Maydeu-Olivares, A., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kroonenberg, P.M.; Greenacre, M.J. Correspondence Analysis. Documentos de Trabajo 2004, 2, 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozmus, D. Correspondence analysis. In Methods of Statistical Multivariate Analysis in Marketing Research; Gatnar, E., Walesiak, M., Eds.; Akademia Ekonomiczna im. Oskara Lange Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2004; pp. 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Barczak, A. The Expectations of the Residents of Szczecin in the Field of Telematics Solutions after the Launch of the Szczecin Metropolitan Railway. Information 2021, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, A.; Dembińska, I.; Rostkowski, T.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Rozmus, D. Structure of Remuneration as Assessed by Employees of the Energy Sector—Multivariate Correspondence Analysis. Energies 2021, 14, 7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Justice and Consumer Directorate—General. Equal Pay? Time to Close the Gap. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/factsheet-gender_pay_gap-2019.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Sönnichsen, N. Global Energy Industry’s Salaries by Sector and Region 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1197240/salaries-of-employees-in-the-energy-industry-worldwide/ (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Moniz, E.; Terry, D.; Jordan, P.; Pablo, J.; Fazell, S.; Young, R.; Schirch, M.; Kenderdine, M.; Hezir, J.S.; Ellis, D.; et al. BW Research Partnership. In Wages, Benefits and Change: A Supplemental Report to the Annual US Energy and Employment Report; The Energy Futures Initiative (EFI): Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UK Salaries in Renewable Energy Sector on the Rise. 2019. Available online: https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/salaries-in-renewable-energy/71653/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

| Dominant Criteria of Fairness | Model Name |

|---|---|

| Final result | Ares |

| Efficiency and commitment | Apollo |

| Contribution to results and accountability | Zeus |

| Amount of work | Hephaestus |

| Working time | Chronos |

| Objective needs, e.g., family situation | Demeter |

| Seniority and position | Hera |

| Employee evaluation by the organization | Aphrodite |

| Risk taken and sacrifice made | Prometheus |

| Balanced impact of all these criteria | Athena |

| Variable | Response Codes | |

|---|---|---|

| SEX | Gender of the respondent | 1: male 2: female |

| AGE | Respondent age | 1: 8–24 years 2: 25–34 years 3: 35–44 years 4: 45–59 years 5: over 60 years |

| EDUC | Respondent education | 1: basic education 2: vocational education 3: secondary education 4: higher education |

| P1_01 | I know the rules of establishing remuneration in my company | 1: I strongly disagree 2: I rather disagree 3: I neither agree nor disagree 4: I rather agree 5: I definitely agree |

| P1_02 | My remuneration is adequate to the job I do | |

| P1_03 | My direct supervisor ensures appropriate remuneration for his/her employees | |

| P1_04 | The rules of remuneration in my company are transparent | |

| P1_05 | My current remuneration is fair | |

| P1_06 | I am proud of my work | |

| P1_07 | My job gives me satisfaction | |

| P1_08 | I am willing to undertake additional tasks, apart from the mandatory ones | |

| P1_09 | I find my remuneration satisfactory | |

| P1_10 | I am willing to share my knowledge and experience at work | |

| P1_11 | I feel used at work | |

| P1_12 | Employees who do similar jobs to mine receive similar remuneration to mine | |

| P1_13 | The company I work for cares about its image as an employer also by setting remuneration | |

| P2 | How would you rate your current remuneration? | 1: He cannot afford to meet his basic needs, he has to use the help of others 2: Afford the basic needs (i.e., fees, bills, food) 3: Stand for the satisfaction of needs and pleasures 4: To be able to meet the needs and additionally save |

| P5_1 | How important is salary? | 1: Definitely irrelevant 2: Rather irrelevant 3: Neither significant or negligible 4: Rather significant 5: Definitely significant |

| P5_2 | How important is job security? | |

| P5_3 | How important is development and promotion opportunities? | |

| P5_4 | How important is independence and doing what you like at work? | |

| P5_5 | How important is atmosphere and contact with people? | |

| P6_1 | What should influence the fact that people in the same position should earn more than others? | 1: I strongly disagree 2: I rather disagree 3: I neither agree nor disagree 4: I rather agree 5: I definitely agree |

| P6_2 | What should influence the fact that people in the same position should earn more than others?—they work after hours (stay longer at work) | |

| P6_3 | What should influence the fact that people in the same position should earn more than others?—have more responsibilities than others | |

| P6_4 | What should influence the fact that people in the same position should earn more than others?—they perform more difficult, more important tasks for the company | |

| P6_5 | What should influence the fact that people in the same position should earn more than others?—are more often praised by superiors | |

| P6_6 | What should influence the fact that people in the same position should earn more than others?—they have more experience; they have more seniority | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barczak, A.; Marska-Dzioba, N.; Rostkowski, T.; Rozmus, D. Multiple Correspondence Analysis in the Study of Remuneration Fairness: Conclusions for Energy Companies—Case Study of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 7942. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14237942

Barczak A, Marska-Dzioba N, Rostkowski T, Rozmus D. Multiple Correspondence Analysis in the Study of Remuneration Fairness: Conclusions for Energy Companies—Case Study of Poland. Energies. 2021; 14(23):7942. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14237942

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarczak, Agnieszka, Natalia Marska-Dzioba, Tomasz Rostkowski, and Dorota Rozmus. 2021. "Multiple Correspondence Analysis in the Study of Remuneration Fairness: Conclusions for Energy Companies—Case Study of Poland" Energies 14, no. 23: 7942. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14237942

APA StyleBarczak, A., Marska-Dzioba, N., Rostkowski, T., & Rozmus, D. (2021). Multiple Correspondence Analysis in the Study of Remuneration Fairness: Conclusions for Energy Companies—Case Study of Poland. Energies, 14(23), 7942. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14237942