Trade, Climate and Energy: A New Study on Climate Action through Free Trade Agreements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Trade, Climate Action and Energy

2.1. Core Discussion

- Carbon-related measures: these have taken many forms. Carbon tariffs typically target emissions arising from internationally transported goods, while carbon trading and market measures are usually based on emissions permit systems. Carbon sinks primarily concern the emission mitigation services provided by forests and forestry plantations, and often linked to carbon trading offset arrangements [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

- Clean energy sector development: trade, energy and often industrial policy measures focused on developing the productive (and hence trading) capacity of various decarbonising, zero- or low-emission technologies such as renewable energy and energy efficiency, these also being core climate-relevant products targeted for trade promotion and liberalisation [27,28,29,30] as noted below.

- Promotion and liberalisation of trade in climate-relevant products: with the aim of directly expanding trade in goods and services that address climate change, including the removal of barriers such as import duties [31,32,33,34,35]. This domain is hence closely linked with the above domain and can extend to trade-related foreign direct investment (FDI) issues also.

- Environmental and technical standards: that facilitate rather than hinder trade in climate-relevant products, such as common or mutually compatible standards implemented by trade partners or agreeing to comply with each other’s standards where these differ [36,37,38]. Emission standards relating to the energy used in internationally traded vehicles are a common example.

- Trade and climate governance regimes, and their interaction: as climate change is essentially viewed as a global-level issue and trade has become increasingly globalised, this domain has centred on the respective roles of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and World United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which along with other international institutions such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) began to address trade-climate issues from the early 1990s [32,44,45,46,47].

2.2. Assessing the Impact of FTAs

2.3. Previous Studies on Climate Action through FTAs

3. Methodology

4. What Kinds of Climate Action through FTAs, and What Likely Impacts?

4.1. What Kinds of Climate Action Are FTAs Specifically Promoting?

- Optional—parties do not expressly commit to co-operation on climate action but rather leave it optional, often using conditional language. Examples of key coded words relevant here are ‘may’, ‘possible’, and ‘potential’.

- Intentional—explicit statements of intent to co-operate, often with climate-relevant issues identified, but lacking detail on actions, methods and objectives. Key coded words here included ‘shall’, ‘will’, and ‘in order to’.

- Action-Structured—specific co-operative actions are outlined in detail within an actional framework or loose governance structure but with no set targets or schedules. Here, key coded words covered various types of action (e.g., workshops, training, information exchange, technology transfer, joint projects, technology development, infrastructure development) and at times involved agencies with reference to some sort of co-operation or governance process, e.g., ‘regular dialogue’.

- Programmatic—the agreement contains a programmatic plan of specified actions, targets and schedules for co-operation in a well-defined governance structure with key coded words (e.g., plan and strategy, with reference to numeric targets, timeframes, and agencies) reflecting this. The governance structure aspect has links with ‘institutionalised co-operation discussed later.

- Institutionalised—co-operation is overseen or managed by a newly established institutional body created by the FTA on its implementation. This is a higher-form of aforementioned ‘governance structure’ in this context (e.g., a Co-operation Committee or similar agency) either specifically charged with responsibility for climate-relevant co-operation between signatory parties or with all trade-related co-operation outlined in the agreement.

- Assistive—commitment of parties to co-operate on climate action capacity-building issues (e.g., technology transfer, training) principally aimed at assisting the less developed trade partner.

- Multilateral-Supportive—pledges to co-operate in supporting wider international and multilateral efforts on climate action.

- A.

- Address or remove non-tariff barriers (NTBs) in environmental goods and services (EGS) trade/FDI generally—assumed to also cover climate-relevant products.

- B.

- Address or remove NTBs in climate-relevant trade/FDI specifically—where climate-relevant products are explicitly referred to.

- C.

- Remove any obstacles or barriers generally to climate-relevant or EGS products trade/FDI—broader in scope than the above.

- D.

- Eliminate tariffs on EGS trade between the FTAs parties generally—on this particular measure and again assumed to cover climate-relevant products.

- E.

- Work in international fora to liberalise EGS trade globally—thus extending beyond the trade of the FTA signatory parties.

- F.

- Free movement of business-persons facilitating EGS trade and FDI—particularly pertinent to climate-relevant services trade.

4.2. How Effective a Potential Positive Impact on Climate Action?

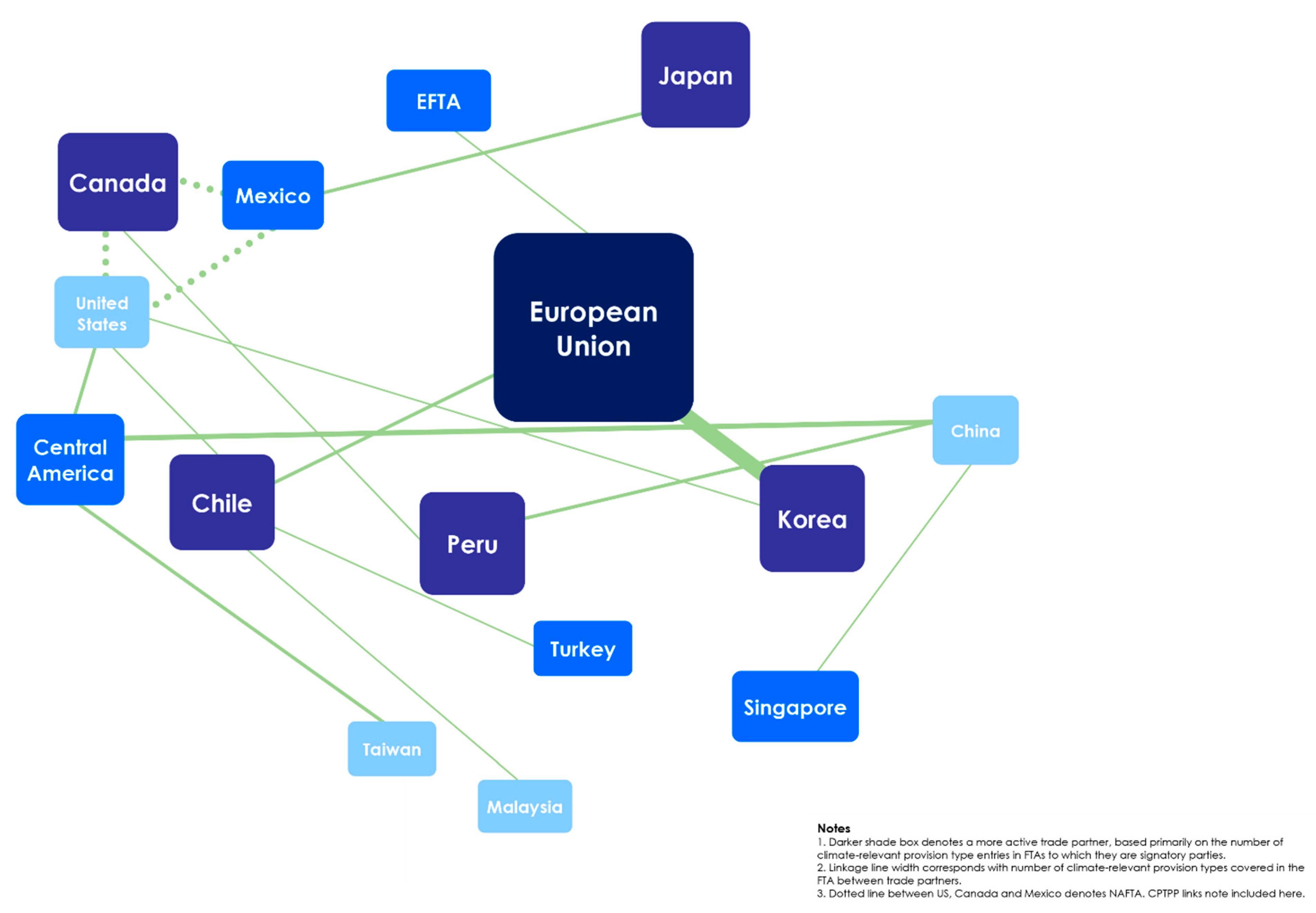

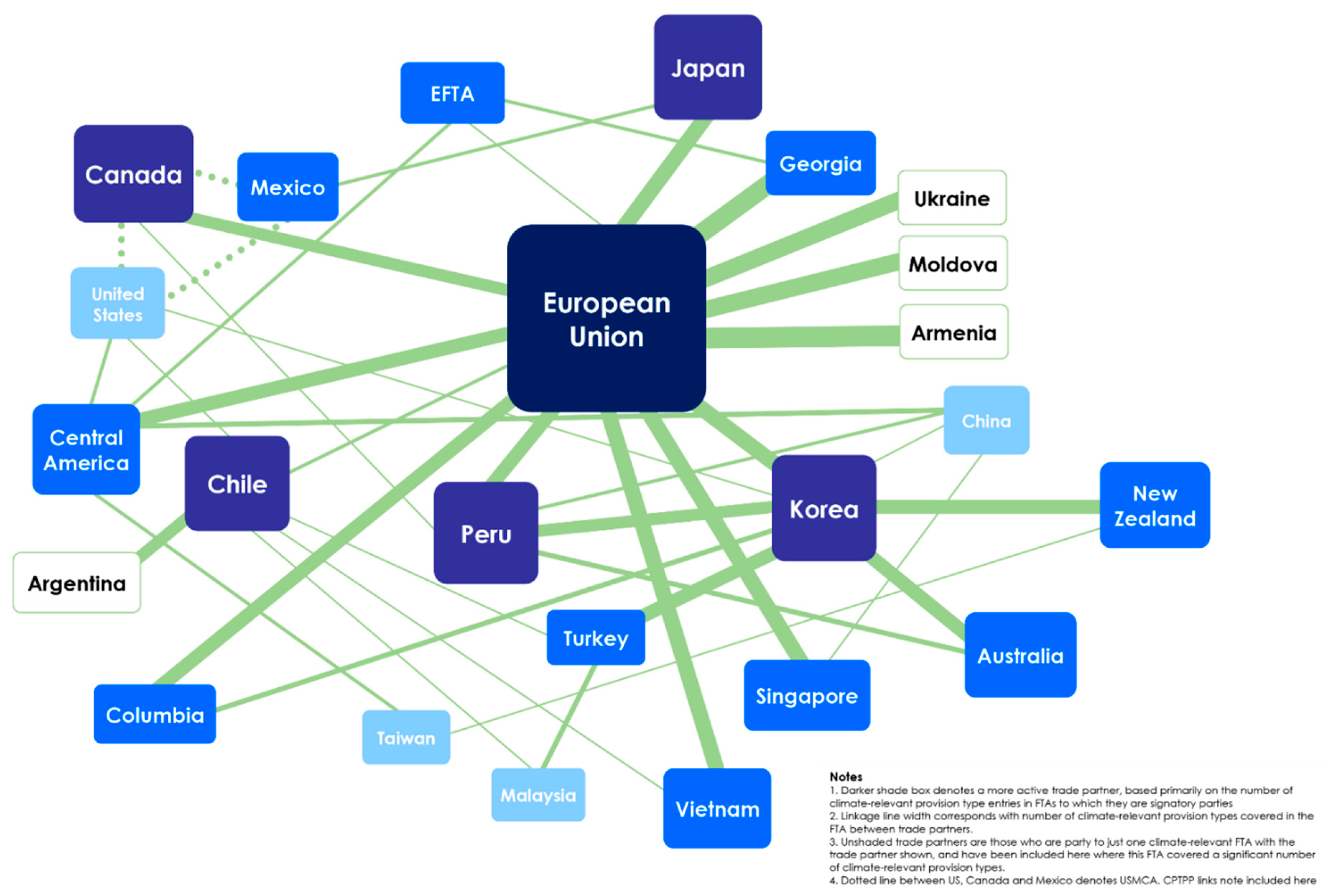

5. Climate Action Norm Leadership and Influence in FTAs

5.1. Norms Analysis: A General Overview

5.2. Climate Norms Leaders and Influencers?

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. Database on Trade; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organisation/WTO Regional Trade Agreements Database 2021, WTO Secretariat: Geneva. Available online: https://rtais.wto.org (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Bernauer, T.; Nguyen, Q. Free Trade and/or Environmental Protection? Glob. Environ. Politics 2015, 15, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A. Trade, the Pollution Haven Hypothesis and Environmental Kuznets Curve: Examining the Linkages. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, N.C.; Lorente, D.B. The Linkage between Economic Growth, Renewable Energy, Tourism, CO2 Emissions, and International Trade: The Evidence for the European Union. Energies 2020, 13, 4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO-UNEP. Trade and Climate Change 2009; WTO Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abman, R.; Lundberg, C. Does Free Trade Increase Deforestation? The Effects of Regional Trade Agreements. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 7, 35–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.; Hertwich, E. CO2 Embodied in International Trade with Implications for Global Climate Policy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Carbon Footprint of Global Trade; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Partain, R.A. Climate Change, Green Paradox Models and International Trade Rules. In Research Handbook on Climate Change and Trade Law; Delimatsis, P., Ed.; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Trade and the Environment; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Methodologies for Trade and Environmental Reviews; OECD: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hayhoe, K. Foreword. In Ecotheology; Jorgenson, K.A., Padgett, A.G., Eds.; Eerdmans: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, S. The Strategy of Trade Sanctions in International Environmental Agreements. Resour. Energy Econ. 1997, 19, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaytor, B.; Cameron, J. Taxes for Environmental Purposes: The Scope for Border Tax Adjustment under WTO Rules; World Wildlife Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Demaret, P.; Stewardson, R. Border tax adjustments under GATT and EC law, and general implications for environmental taxes. J. World Trade 1994, 28, 5–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hoerner, A.; Muller, F. Carbon Taxes for Climate Protection in a Competitive World; University of Maryland Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Von Moltke, K. International trade, technology transfer and climate change. In Confronting Climate Change; Mintzer, I.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cottier, T.; Nartova, O.; Shingal, A. The Potential of Tariff Policy for Climate Change Mitigation: Legal and Economic Analysis; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, G. The World Trade Organisation, Kyoto and Energy Tax Adjustments at the Border. J. World Trade 2004, 38, 395–423. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, K. International Carbon Trade and Domestic Climate Politics. Glob. Environ. Politics 2015, 15, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, D.; Hepburn, C.; Ruta, G. Trade, climate change, and the political game theory of border carbon adjustments. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2012, 28, 368–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, M.A.; Van Asselt, H.; Das, K.; Droege, S.; Verkuijl, C. Designing Border Carbon Adjustments for Enhanced Climate Action. Am. J. Int. Law 2019, 113, 433–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. Making Border Carbon Adjustments Work in Law and Practice; Tax Policy Centre: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vranes, E. Carbon Taxes, PPMs and the GATT. In Research Handbook on Climate Change and Trade Law; Delimatsis, P., Ed.; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading and the World Trading System. J. World Trade 1998, 32, 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, C.M. Clean Energy Trade Governance: Reconciling Trade Liberalism and Climate Interventionism? New Political Econ. 2018, 23, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E15 Initiative Clean Energy Technologies and the Trade System: Proposals and Analysis; ICTSD/E15 Initiative: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ICTSD. Linking Trade, Climate Change and Energy; International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. The Rise of Renewable Energy Protectionism: Emerging Trade Conflicts and Implications for Low Carbon Development. Glob. Environ. Politics 2014, 14, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, K.; Shariff, N. The inclusion of border carbon adjustments in preferential trade agreements: Policy implications. Carbon Clim. Law Rev. 2012, 6, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- ICTSD. Climate Change and Sustainable Energy Measures in Regional Trade Agreements; ICTSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Arcas, R. Trade Proposals for Climate Action. Trade Law Dev. 2014, 6, 11–54. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, J.F.; Dür, A.; Lechner, L. Mapping the Trade and Environment Nexus: Insights from a New Data Set. Glob. Environ. Politics 2018, 18, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, C.; Schwab, J.; Berger, A.; Morin, J.-F. Do environmental provisions in trade agreements make exports from developing countries greener? World Dev. 2020, 129, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaens, I.; Postnikov, E. Greening up: The effects of environmental standards in EU and US trade agreements. Environ. Politics 2017, 26, 847–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, K.; Cottier, T. Addressing climate change under preferential trade agreements: Towards alignment of carbon standards under the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, H.; Nakada, M.; Shibata, A. Free Trade Agreements with Environmental Standards. In Kyoto Institute for Economic Research Discussion Paper Series; Kyoto University: Kyoto, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ICTSD. International Transport, Climate Change and Trade; ICTSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Monkelbaan, J. Transport, Trade and Climate Change: Carbon Footprints, Fuel Subsidies and Market-based Measures; ICTSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, J.S. The environmental bias of trade policy. Q. J. Econ. 2021, 136, 831–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohringer, F.; Grether, J.M.; Mathys, N.A. Trade and Climate Policies: Do Emissions from International Transport Matter? World Econ. 2013, 36, 280–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yasmeen, R.; Li, Y.; Hafeez, M.; Ihtsham Ul Haq Padda, I.U.H. Free Trade Agreements and Environment for Sustainable Development: A Gravity Model Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, R. Understanding the Interplay between the Climate and Trade Regimes. In Climate and Trade Policies; UNEP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Epps, T.; Green, A. Reconciling Trade and Climate: How the WTO Can Help Address Climate Change; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Werksman, J. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading and the WTO. Rev. Eur. Community Int. Environ. Law 1999, 8, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Trade Organisation/WTO. The Interface between the Trade and Climate Change Regimes: Scoping the Issues; WTO Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Staff Working Paper ERSD-2011-1. [Google Scholar]

- Enerdata. Global Energy Trends; Enerdata: Grenoble, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Arcas, R.; Abu Gosh, E.S. Energy Trade as a Special Sector in the WTO: Unique Features, Unprecedented Challenges and Unresolved Issues; School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper Series; Queen Mary University of London: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. Energy Trade and GATT Rules: Is Something Missing? Hinrich Foundation. Available online: https://www.hinrichfoundation.com/research/tradevistas/wto/energy-trade (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- Selivanova, Y. Regulation of Energy in International Trade Law; Kluwer Law International: The Hague, Poland, 2011; WTO, NAFTA and Energy Charter 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, C.M. Understanding the Energy Diplomacies of East Asian States. Mod. Asian Stud. 2013, 47, 935–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogoretskyy, V.; Melnyk, S. Energy security, climate change and trade: Does the WTO provide for a viable framework for sustainable energy security? In Research Handbook on Climate Change and Trade Law; Delimatsis, P., Ed.; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T. Explaining Energy Disputes at the World Trade Organisation. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2017, 17, 391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Arcas, R. Climate Change and International Trade; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, J.F.; Jinnah, S. The untapped potential of preferential trade agreements for climate governance. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asselt, H. The Fragmentation of Global Climate Governance: Consequences and Management of Regime Interactions; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cottier, T.; Payosova, T. Common Concern and the Legitimacy of the WTO in Dealing with Climate Change. In Research Handbook on Climate Change and Trade Law; Delimatsis, P., Ed.; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brandi, C. Trade Elements in Countries’ Climate Contributions under the Paris Agreement; ICTSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, T.L. Trade Policies and Climate Change Policies: A Rapidly Expanding Joint Agenda. World Econ. 2010, 33, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorssen, A.M. UNFCCC, the K UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol, and the WTO—Brewing Conflicts or Brewing Conflicts or Are They Mutually Supportive. Denver J. Int. Law Policy 2020, 36, 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- ICTSD. Multilateral Negotiations at the Intersection of Trade and Climate Change; ICTSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kulovesi, K. Real or imagined controversies—A climate law perspective on the growing links between the international trade and climate change regimes. Trade Law Dev. 2014, 6, 55–92. [Google Scholar]

- Van Asselt, H.; Kulovesi, K. Seizing the opportunity: Tackling fossil fuel subsidies under the UNFCCC. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2017, 17, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosbey, A. Trade and Climate Change: Issues for the G20 Agenda; Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung: Lima, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heubaum, H.; Biermann, F. Integrating global energy and climate governance: The changing role of the International Energy Agency. Energy Policy 2015, 87, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environmental Programme/UNEP. Climate and Trade Policies in a Post-2012 World; UNEP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. International Trade and Climate Change; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Breinlich, H. The Economic Effects of Free Trade Agreements. In Handbook of International Trade Agreements; Breinlich, H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, S.A. The Impact of Trade Agreements: New Approach, New Insights. In IMF Working Paper Series; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, S.L.; Yotov, Y.V.; Zylkinc, T. On the widely differing effects of free trade agreements: Lessons from twenty years of trade integration. J. Int. Econ. 2019, 116, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, P.H.; Larch, M.; Yotov, Y.V. Gravity-Model Estimation with Time-Interval Data: Revisiting the Impact of Free Trade Agreements. In CESifo Working Paper Series; Centre for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo): Munich, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Head, K.; Mayer, T. Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In Handbook of International Economics; Gopinath, G., Helpman, E., Rogoff, K., Eds.; Elsevier: The Hague, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, S.; Choutagunta, A.; Sahu, S.K. Evaluating Asian Free Trade Agreements: What Does Gravity Model Tell Us? Foreign Trade Rev. 2021, 56, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yasmeen, R.; Cai, Z. The impact of preferential trade agreements on bilateral trade: A structural gravity model analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.; Kwak, D.W.; Tang, K.K. The trade effects of tariffs and non-tariff changes of preferential trade agreements. Econ. Model. 2018, 70, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M. The Rising Importance of Non-tariff Measures and their use in Free Trade Agreements Impact Assessments. In Global Development and Environment Institute Working Paper Series; Tufts University: Medford, OR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Okabe, M. Impact of Free Trade Agreements on Trade in East Asia. In ERIA Discussion Paper Series; Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ciuriak, N.; Ciuriak, D. Climate Change and the Trading System: Implications of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Int. Trade J. 2016, 30, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C. Mega-Regional Trade Agreements and Post-2015 Climate Protection: Bridging the Gap. J. Eur. Environ. Plan. Law 2015, 12, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, J. Climate Change in the TPP and the TTIP. In Research Handbook on Climate Change and Trade Law; Delimatsis, P., Ed.; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, J.F.; Michaud, N.; Bialais, C. Trade negotiations and climate governance: The EU as a pioneer, but not (yet) a leader. In IDDRI Issue Brief; Institut du Développement Durableet des Relations Internationales (IDDRI): Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jinnah, S.; Morin, J.F. Greening through Trade: How American Trade Policy is Linked to Environmental Protection Abroad; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, B.F.; Miller, W.L. Doing Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- King, N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organisational Research; Cassell, C., Symon, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- King, N. Doing Template Analysis. In Qualitative Organisational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges; Symon, G., Cassell, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, F.W.; Turnock, D. Environmental Problems in Eastern Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Campi, M.; Dueñas, M. Intellectual property rights, trade agreements, and international trade. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, K.; Kim, H.S.; Yoshimi, T. Exchange rate and utilization of free trade agreements: Focus on rules of origin. J. Int. Money Financ. 2017, 75, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, M.; Wignaraja, G. Asia’s Free Trade Agreements: How Is Business Responding? Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, C.; Mollborn, S. Norms: An Integrated Framework. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2020, 46, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnemore, M.; Sikkink, K. International Norm Dynamics and Political Change. Int. Organ. 1998, 52, 887–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmaier, W. The power of economic ideas–through, over and in–political time: The construction, conversion and crisis of the neoliberal order in the US and UK. J. Eur. Public Policy 2016, 23, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. The Social Foundations of World Trade: Norms, Community, and Constitution; CUP: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sicurelli, D. The EU as a norm promoter through trade. The perceptions of Vietnamese elites. Asia Eur. J. 2015, 13, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Power of discourse in free trade agreement negotiation. Leiden J. Int. Law 2019, 32, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allee, T.; Lugg, A. Who wrote the rules for the Trans-Pacific Partnership? Res. Politics 2016, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.F.; Karlsson, C.; Hjerpe, M. Assessing the European Union’s global climate change leadership. J. Eur. Integr. 2017, 39, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnah, S.; Morgera, E. Environmental Provisions in American and EU Free Trade Agreements: A Preliminary Comparison and Research Agenda. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Law 2013, 22, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities (CEC). White Paper on Growth, Competitiveness and Employment; CEC: Brussels, Belgium, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jinnah, S.; Lindsay, A. Diffusion through Issue Linkage: Environmental Norms in US Trade Agreements. Glob. Environ. Politics 2016, 16, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croquet, N.A.J. The climate change norms under the EU-Korea Free Trade Agreement: Between soft and hard law. In Global Governance through Trade: EU Policies and Approaches; Wouters, J., Marx, A., Geraets, D., Natens, B., Eds.; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, J.F.; Rochette, M. Transatlantic convergence of preferential trade agreements environmental clauses. Bus. Politics 2017, 19, 621–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirlot, A. The environmental dimension of free trade agreements: A European perspective. Rev. Int. De Droit Économique 2020, 2, 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Manners, I.J. Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms? J. Common Mark. Stud. 2002, 40, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damro, C. Market power Europe: Exploring a dynamic conceptual framework. J. Eur. Public Policy 2015, 22, 1336–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possenti, S. The Trade-Climate Nexus: Assessing the European Union’s Institutionalist Approach. In EU Diplomacy Paper, No. 04/2019; College of Europe: Bruges, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond, B. Three ways of speaking Europe to the world: Markets, peace, cosmopolitan duty and the EU’s normative power. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2013, 16, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, C.M. Renewable Energy in East Asia: Towards a New Developmentalism; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, T.H. Green Growth Policy in the Republic of Korea: Its Promises and Pitfalls. Korea Obs. 2010, 41, 379–414. [Google Scholar]

- Song, A.Y. Linking trade and environment in emerging economies: Korea’s ambition for making green free trade agreements. Pac. Rev. 2021, 34, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles-Brugge, G. Resisting Protectionism after the Crisis: Strategic Economic Discourse and the EU-Korea Free Trade Agreement. New Political Econ. 2011, 16, 627–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H. The new politics of trade negotiations: The case of the EU-Korea FTA. J. Eur. Integr. 2017, 39, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles-Brugge, G. The power of economic ideas: A constructivist political economy of EU trade policy. J. Contemp. Eur. Res. 2013, 9, 597–617. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X. Phoenix from the Ashes CPTPP Meaning for Asia-Pacific (And Global) Investment. Asian J. WTO Int. Health Law Policy 2020, 15, 567–652. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Provision Type | Original TREND Designation (and Codebook Number/s) | Empirical Domains | First FTA to Include |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Generalised only climate-relevant interactions between energy policies and the environment | Interaction between energy policies and the environment (4.03) | Clean energy sector development | US–Chile (2003) |

| 2 | Carbon trading and market instruments | Specific economic or market instruments (6.03.01) | Carbon-related measures | EU–Korea (2010) |

| 3 | Promotion of trade and/or foreign investment in climate-relevant products | Promote environmental goods and services (7.01) | Promotion and liberalisation of trade in climate-relevant products; clean energy sector development | US–Central America–Dominican Republic (2004) |

| 4 | Promotion of renewable energy development | Same designation (10.15.01.01) | Clean energy sector development | Economic Community of Central African States (1983) |

| 5 | Promotion of energy efficiency technologies | Same designation (10.15.01.02) | Clean energy sector development | EU–Hungary (1991) |

| 6 | Reduction in GHG emissions | Same designation (10.15.02.01) | Trade transportation; Clean energy sector development | EU–South Africa (1999) |

| 7 | Climate change adaptation | Same designation (10.15.02.02) | Multiple domains | China–Costa Rica (2010) |

| 8 | Co-operation on climate change | Same designation (10.15.02.03) | Multiple domains | EU–Hungary (1991) |

| 9 | Harmonization of legislations related to climate change | Same designation (10.15.02.04) | Trade and climate regimes, and their interaction | EU–Ukraine (2014) |

| 10 | Other norms on climate change | Same designation (10.15.02.05) | Multiple domains | Japan–Brunei (2007) |

| 11 | Environmental standards on vehicle emissions | Same designation (10.18) | Environmental and technical standards; clean energy sector development | European Economic Area (1992) |

| 12 | Ratification, implementation or references generally of UNFCCC accords | Same designation (14.01.10, 14.02.09.01, 14.04.10) | Trade and climate regimes, and their interaction | Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (1993) |

| 13 | Ratification, implementation, prevalence or references generally of Kyoto Protocol | Same designation (14.01.11, 14.02.10.01, 14.03.11, 14.04.11) | Trade and climate regimes, and their interaction | Japan–Mexico (2004) |

| 14 | Implementation or references generally of the Paris Climate | Same designation (14.02.20 14.04.26) | Trade and climate regimes, and their interaction | Chile–Argentina (2017) |

| No. | Free Trade Agreement | Year Sign | 1. Generalised Only Climate-Relevant Interactions between Energy Policies and the Environment | 2. Carbon Trading and Market Instruments | 3. Promotion of Trade and/or FDI in Climate-Relevant Goods and Services | 4. Promotion of Renewable Energy Development | 5. Promotion of Energy Efficiency Technologies | 6. Reduction in GHG Emissions | 7. Climate Change Adaptation | 8. Co-Operation on Climate Change | 9. Harmonization of Legislations Related to Climate Change | 10. Other Norms on Climate Change | 11. Environmental Standards on Vehicle Emissions | 12. Ratification, Implementation or References Generally of UNFCCC Accords | 13. Ratification, Implementation, Prevalence or References Generally of Kyoto Protocol | 14. Implementation or References Generally of the Paris Climate Agreement | Provisions TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) | 1983 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | African Economic Community (AEC) | 1991 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | EU–Hungary FTA | 1991 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | EU–Poland FTA | 1991 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 5 | European Economic Area (EEA)–EU–EFTA | 1992 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) | 1992 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 7 | EU–Bulgaria FTA | 1993 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 8 | EU–Romania FTA | 1993 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 9 | EU–Slovakia FTA | 1993 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 10 | Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) | 1993 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 11 | Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) | 1993 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 12 | Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) | 1994 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 13 | EU–South Africa FTA | 1999 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 14 | East African Community (EAC) | 1999 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 15 | EU–Chile FTA | 2002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 16 | US–Chile FTA | 2003 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 17 | US–Central America–Dominican Republic FTA | 2004 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 18 | Japan–Mexico FTA | 2004 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 19 | Taiwan–Guatemala FTA | 2005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 20 | Taiwan–Nicaragua FTA | 2006 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 21 | Taiwan–El Salvador–Honduras FTA | 2007 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 22 | Japan–Brunei FTA | 2007 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 23 | Japan–Indonesia FTA | 2007 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 24 | US–Korea FTA | 2007 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 25 | US–Panama FTA | 2007 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 26 | Canada–Peru FTA | 2008 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 27 | EU–CARIFORUM EPA | 2008 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 28 | China–Singapore FTA | 2008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 29 | Chile–Turkey FTA | 2009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 30 | China–Peru FTA | 2009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 31 | India–Korea FTA | 2009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 32 | Japan–Switzerland FTA | 2009 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 33 | Chile–Malaysia FTA | 2010 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 34 | China–Costa Rica FTA | 2010 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 35 | EU–Korea FTA | 2010 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 36 | Chile–Vietnam FTA | 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 37 | EFTA–Hong Kong FTA | 2011 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 38 | EFTA–Montenegro FTA | 2011 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 39 | Korea–Peru FTA | 2011 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 40 | EU–Central America FTA (Association Agreement embedded) | 2012 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| 41 | EU–Colombia–Peru FTA | 2012 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| 42 | Korea–Turkey FTA | 2012 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| 43 | Canada–Honduras FTA | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 44 | Chile–Thailand FTA | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 45 | Korea–Colombia FTA | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 46 | Colombia–Panama FTA | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 47 | New Zealand–Taiwan FTA | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 48 | EFTA–Bosnia and Herzogovina FTA | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 49 | EFTA–Central America FTA | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 50 | EU–Ukraine FTA | 2014 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| 51 | EU–Moldova FTA | 2014 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| 52 | EU–Georgia FTA | 2014 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| 53 | China–Korea FTA | 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 54 | Australia–Korea FTA | 2014 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 55 | Malaysia–Turkey FTA | 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 56 | Korea–New Zealand FTA | 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 57 | EFTA–Philippines FTA | 2016 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 58 | EU–East Africa Community (EAC) EPA | 2016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 59 | EFTA–Georgia FTA | 2016 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 60 | Chile–Argentina FTA | 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| 61 | EU–Canada FTA (CETA) | 2017 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 62 | EU–Armenia FTA | 2018 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| 63 | US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 64 | Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 65 | EU–Japan FTA | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 66 | EU–Singapore FTA | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 67 | Australia–Peru FTA | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 68 | EU–Vietnam FTA | 2019 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| 69 | Chile–Indonesia FTA | 2020 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 3 | 9 | 30 | 41 | 36 | 27 | 16 | 33 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 245 |

| No. | Free Trade Agreement | Year Sign | Thematic Heading | LEVEL | FEATURES | Words | Cooperation as % of All Climate-Relevant Provisions Text | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optional | Intentional | Action-Structured | Programmatic | Institutionalised | Assistive | Multilateral-Supportive | ||||||

| 1 | Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) | 1983 | Energy and Natural Resources | 1 | 95 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 2 | African Economic Community (AEC) | 1991 | Industry, S&T, Energy, Environment | 1 | 118 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 3 | EU–Hungary FTA | 1991 | Economic (Energy, Environment) | 1 | 260 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 4 | EU–Poland FTA | 1991 | Economic (Energy, Environment) | 1 | 245 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 5 | European Economic Area (EEA)–EU–EFTA | 1992 | _ | _ | _ | |||||||

| 6 | North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) | 1992 | _ | _ | _ | |||||||

| 7 | EU–Bulgaria FTA | 1993 | Economic (Energy, Environment) | 1 | 210 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 8 | EU–Romania FTA | 1993 | Economic (Energy, Environment) | 1 | 1 | 112 | 100.0 | |||||

| 9 | EU–Slovakia FTA | 1993 | Economic (Energy, Environment) | 1 | 1 | 162 | 100.0 | |||||

| 10 | Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) | 1993 | Energy, Environment | 1 | 1 | 337 | 100.0 | |||||

| 11 | Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) | 1993 | Industry, S&T, Energy; Meteorological | 1 | 131 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 12 | Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) | 1994 | Environmental Protection | 1 | 103 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 13 | EU–South Africa FTA | 1999 | Economic (Energy), Environment | 1 | 1 | 396 | 100.0 | |||||

| 14 | East African Community (EAC) | 1999 | Infrastructure and Services (Energy, Meteorological) | 1 | 186 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 15 | EU–Chile FTA | 2002 | Economic (Energy) | 1 | 1 | 127 | 100.0 | |||||

| 16 | US–Chile FTA | 2003 | Environment | 1 | 1 | 104 | 100.0 | |||||

| 17 | US–Central America–Dominican Republic FTA | 2004 | Environment | 1 | 1 | 162 | 100.0 | |||||

| 18 | Japan–Mexico FTA | 2004 | Environment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 124 | 100.0 | ||||

| 19 | Taiwan–Guatemala FTA | 2005 | Energy | 1 | 1 | 123 | 100.0 | |||||

| 20 | Taiwan–Nicaragua FTA | 2006 | Environment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 108 | 100.0 | ||||

| 21 | Taiwan–El Salvador–Honduras FTA | 2007 | Energy | 1 | 1 | 106 | 100.0 | |||||

| 22 | Japan–Brunei FTA | 2007 | Energy (Environment) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 199 | 42.2 | ||||

| 23 | Japan–Indonesia FTA | 2007 | Energy and Mineral Resources | 1 | 1 | 1 | 147 | 19.7 | ||||

| 24 | US–Korea FTA | 2007 | _ | _ | _ | |||||||

| 25 | US–Panama FTA | 2007 | Environmental | 1 | 1 | 59 | 100.0 | |||||

| 26 | Canada–Peru FTA | 2008 | _ | _ | _ | |||||||

| 27 | EU–CARIFORUM EPA | 2008 | Eco-Innovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 159 | 80.3 | ||||

| 28 | China–Singapore FTA | 2008 | Economic | 1 | 52 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 29 | Chile–Turkey FTA | 2009 | Environment | 1 | 97 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 30 | China–Peru FTA | 2009 | Forestry and Environmental Protection | 1 | 1 | 1 | 226 | 100.0 | ||||

| 31 | India–Korea FTA | 2009 | Energy | 1 | 206 | 68.9 | ||||||

| 32 | Japan–Switzerland FTA | 2009 | _ | _ | _ | |||||||

| 33 | Chile–Malaysia FTA | 2010 | Environment | 1 | 1 | 385 | 100.0 | |||||

| 34 | China–Costa Rica FTA | 2010 | Agriculture | 1 | 170 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 35 | EU–Korea FTA | 2010 | Trade and Sustainable Development (SD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1429 | 82.3 | ||||

| 36 | Chile–Vietnam FTA | 2011 | Co-operation in general | 1 | 19 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 37 | EFTA–Hong Kong FTA | 2011 | Trade and Environment | 1 | 28 | 27.3 | ||||||

| 38 | EFTA–Montenegro FTA | 2011 | Trade and SD | 1 | 132 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 39 | Korea–Peru FTA | 2011 | SMEs, Environment, Forestry | 1 | 236 | 73.1 | ||||||

| 40 | EU–Central America FTA (Association Agreement embedded) | 2012 | Environment, Trade and SD, Energy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 506 | 73.7 | |||

| 41 | EU–Colombia–Peru FTA | 2012 | Trade and SD (Climate Change) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 463 | 90.7 | ||||

| 42 | Korea–Turkey FTA | 2012 | Trade and SD | 1 | 1 | 93 | 74.2 | |||||

| 43 | Canada–Honduras FTA | 2013 | Environment | 1 | 46 | 47.9 | ||||||

| 44 | Chile–Thailand FTA | 2013 | Economic (Environment) | 1 | 49 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 45 | Korea–Colombia FTA | 2013 | Trade and SD (Forestry, Environment), SMEs | 1 | 158 | 82.5 | ||||||

| 46 | Colombia–Panama FTA | 2013 | Environment | 1 | 36 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 47 | New Zealand–Taiwan FTA | 2013 | _ | _ | _ | |||||||

| 48 | 2013 | _ | _ | _ | ||||||||

| 49 | EFTA–Central America FTA | 2013 | Trade and SD (Forestry) | 1 | 64 | 57.1 | ||||||

| 50 | EU–Ukraine FTA | 2014 | Economic (Energy, Environment, S&T), Trade and SD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 424 | 83.6 | ||||

| 51 | EU–Moldova FTA | 2014 | Economic (Energy, Climate Change), Trade and SD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 473 | 92.6 | ||||

| 52 | EU–Georgia FTA | 2014 | Economic (Energy), Trade and SD, Climate, Maritime | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 517 | 78.8 | |||

| 53 | China–Korea FTA | 2014 | Intellectual Property Rights, Economic (Energy) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 150 | 100.0 | ||||

| 54 | Australia–Korea FTA | 2014 | Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries, Energy, Environment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 368 | 90.4 | ||||

| 55 | Malaysia–Turkey FTA | 2014 | Economic and Technical (Energy, Environment) | 1 | 73 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 56 | Korea–New Zealand FTA | 2015 | Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries, Energy, Environment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 294 | 53.4 | ||||

| 57 | EFTA–Philippines FTA | 2016 | Trade and SD (Forestry) | 1 | 1 | 76 | 55.1 | |||||

| 58 | EU–East Africa Community (EAC) EPA | 2016 | Infrastructure (Energy), Agriculture, Climate Change | 1 | 1 | 1 | 226+ | 100.0 | ||||

| 59 | EFTA–Georgia FTA | 2016 | Trade and SD (Forestry) | 1 | 1 | 82 | 63.6 | |||||

| 60 | Chile–Argentina FTA | 2017 | Trade and Environment (Climate Change) | 1 | 1 | 193 | 58.1 | |||||

| 61 | EU–Canada FTA (CETA) | 2017 | Trade and Environment | 1 | 1 | 275 | 77.5 | |||||

| 62 | EU–Armenia FTA | 2018 | Climate Change, Trade and SD, Energy, Industry | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 976 | 81.5 | |||

| 63 | US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) | 2018 | Environment (Maritime, Air Quality) | 1 | 1 | 175 | 44.9 | |||||

| 64 | Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) | 2018 | Environment (Low-Emission Economy, Maritime) | 1 | 1 | 191 | 60.1 | |||||

| 65 | EU–Japan FTA | 2018 | Trade and SD, Regulatory | 1 | 1 | 1 | 251 | 63.5 | ||||

| 66 | EU–Singapore FTA | 2018 | Renewable Energy, Trade and SD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1228 | 86.7 | ||||

| 67 | Australia–Peru FTA | 2018 | Environment | 1 | 1 | 54 | 42.2 | |||||

| 68 | EU–Vietnam FTA | 2019 | Trade and SD (Climate Change) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1368 | 94.4 | ||||

| 69 | Chile–Indonesia FTA | 2020 | Environment | 1 | 37 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 8 | 18 | 29 | 7 | 15 | 23 | 24 | 249 ave | 84.6% ave | ||||

| No. | Free Trade Agreement | Year Sign | A. Address or Remove NTBs in EGS Trade/FDI Generally | B. Address or Remove NTBs in Climate-Relevant Trade/FDI Specifically | C. Remove Any Obstacles or Barriers Generally to Climate-Relevant or EGS Products Trade/FDI | D. Eliminate Tariffs on All EGS Products | E. Work in International Fora to Liberalise EGS Trade Globally | F. Free Movement of Business Persons Facilitating EGS Trade and FDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | EU–Korea FTA | 2010 | 1 | |||||

| 37 | EFTA–Hong Kong FTA | 2011 | 1 | |||||

| 38 | EFTA–Montenegro FTA | 2011 | 1 | |||||

| 40 | EU–Central America FTA | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 41 | EU–Colombia–Peru FTA | 2012 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 42 | Korea–Turkey FTA | 2012 | 1 | |||||

| 47 | New Zealand–Taiwan FTA | 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 48 | EFTA–Bosnia and Herzogovina FTA | 2013 | 1 | |||||

| 49 | EFTA–Central America FTA | 2013 | 1 | |||||

| 50 | EU–Ukraine FTA | 2014 | 1 | |||||

| 52 | EU–Georgia FTA | 2014 | 1 | |||||

| 54 | Australia–Korea FTA | 2014 | 1 | |||||

| 57 | EFTA–Philippines FTA | 2016 | 1 | |||||

| 59 | EFTA–Georgia FTA | 2016 | 1 | |||||

| 61 | EU–Canada FTA (CETA) | 2017 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 62 | EU–Armenia FTA | 2018 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 63 | US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) | 2018 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 64 | Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) | 2018 | 1 | |||||

| 66 | EU–Singapore FTA | 2018 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 68 | EU–Vietnam FTA | 2019 | 1 | |||||

| TOTAL | 16 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dent, C.M. Trade, Climate and Energy: A New Study on Climate Action through Free Trade Agreements. Energies 2021, 14, 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144363

Dent CM. Trade, Climate and Energy: A New Study on Climate Action through Free Trade Agreements. Energies. 2021; 14(14):4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144363

Chicago/Turabian StyleDent, Christopher M. 2021. "Trade, Climate and Energy: A New Study on Climate Action through Free Trade Agreements" Energies 14, no. 14: 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144363

APA StyleDent, C. M. (2021). Trade, Climate and Energy: A New Study on Climate Action through Free Trade Agreements. Energies, 14(14), 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144363