Secondary Energy Sources and Their Optimization in the Context of the Tax Gap on Petrol and Diesel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

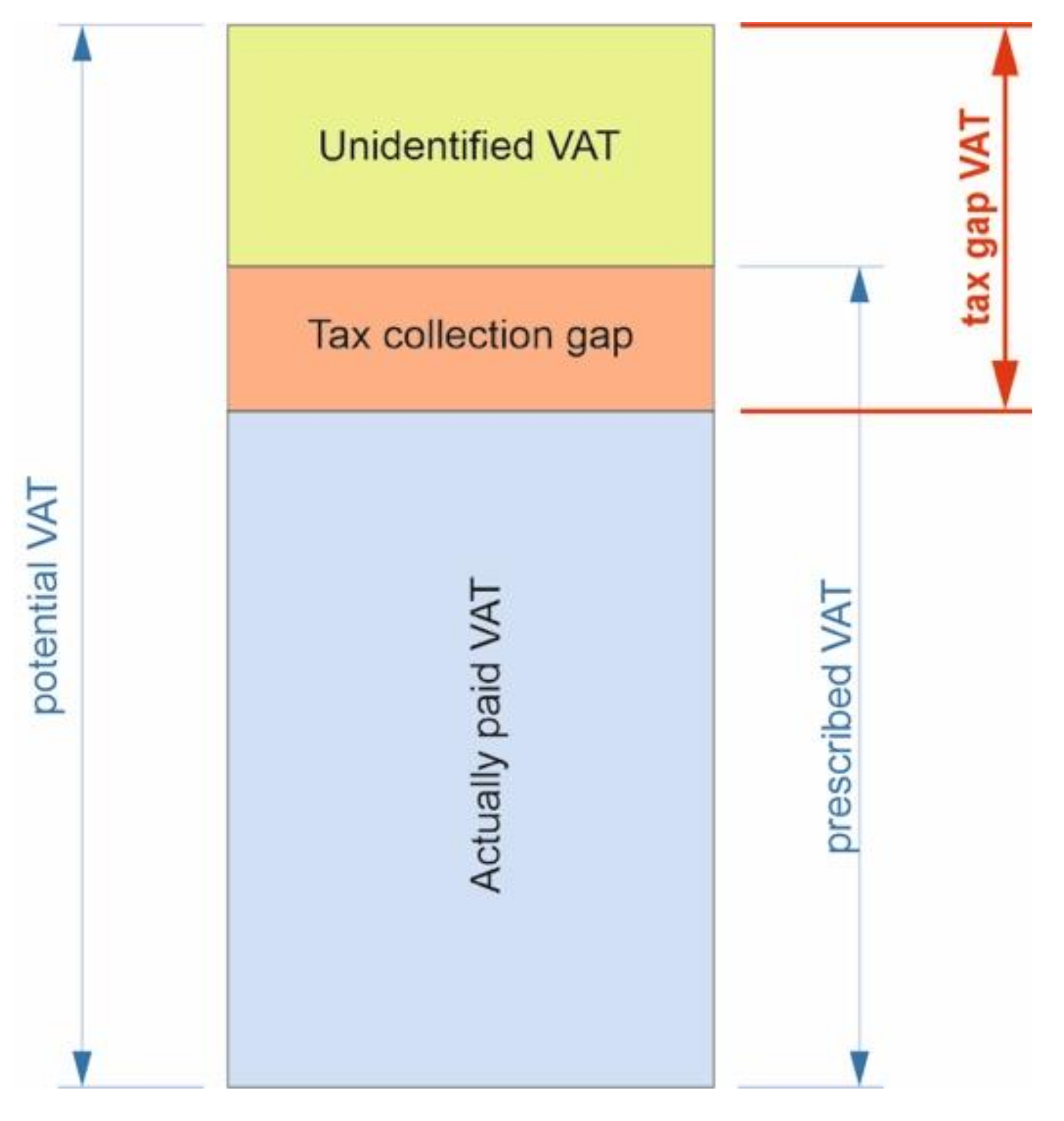

3.1. Theoretical Input to Experimental Analysis

3.2. Tax Gap on Corporate Income Tax

- Unintended mistakes on the side of the taxpayer (e.g., because of insufficient knowledge or misinterpretation of tax legislation);

- Non-payment of tax at firms in bankruptcy proceedings;

- Intended activities of the taxpayer focused on a reduction in the tax duty.

- An estimation of the overall consumption of petrol and diesel according to the number of kilometers driven in the territory of the Slovak Republic and the average consumption;

- The declared consumption of petrol and diesel by the Financial Administration of the Slovak Republic and the tax revenue from fuels;

- A single calculation of the tax gap.

- Incidental findings—results from incidentally selected controls;

- Risk Register—analysis of potential losses from selected corporations and entities;

- Data connection—identification of undeclared income/property by means of data connection from various sources.

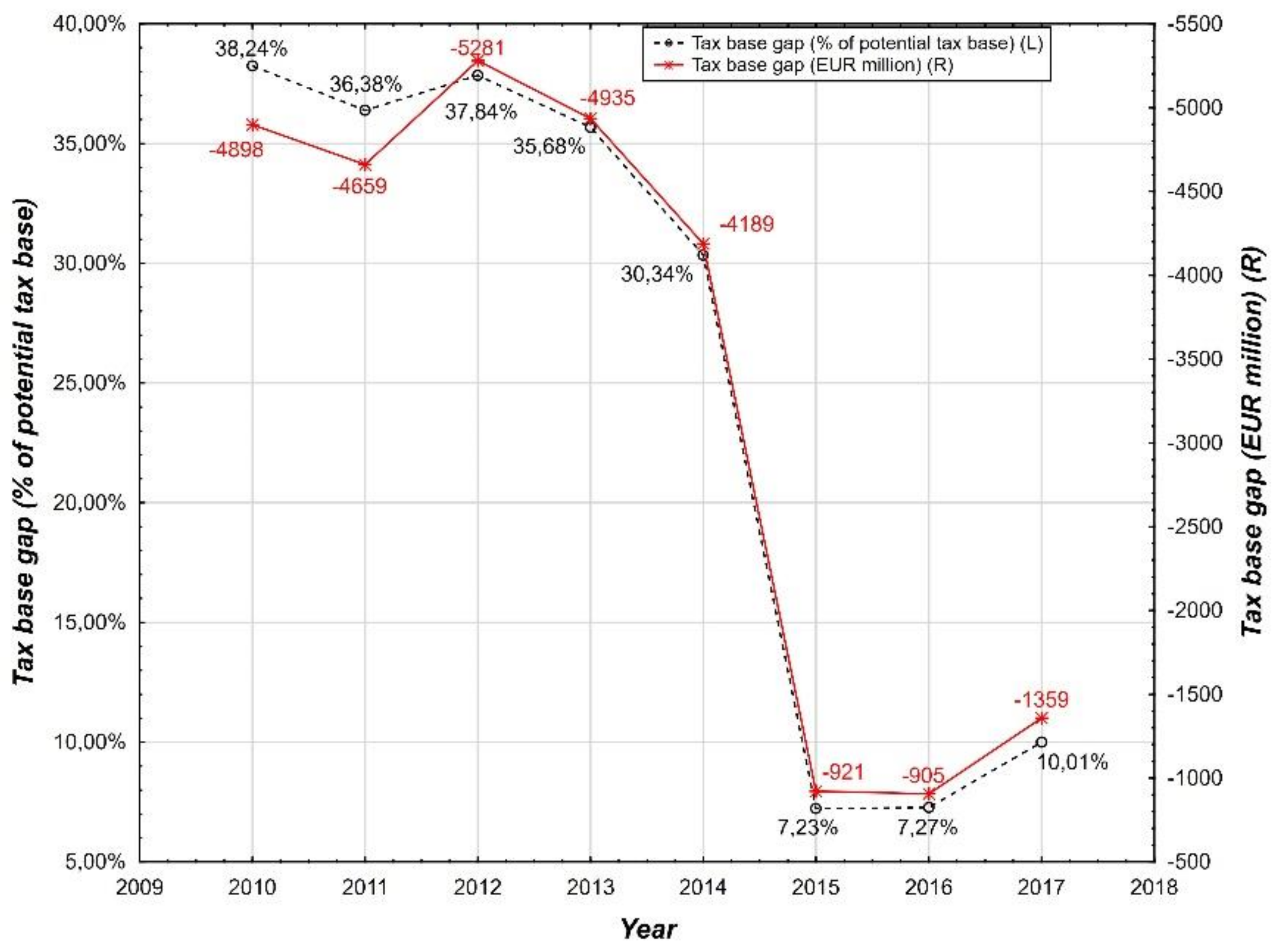

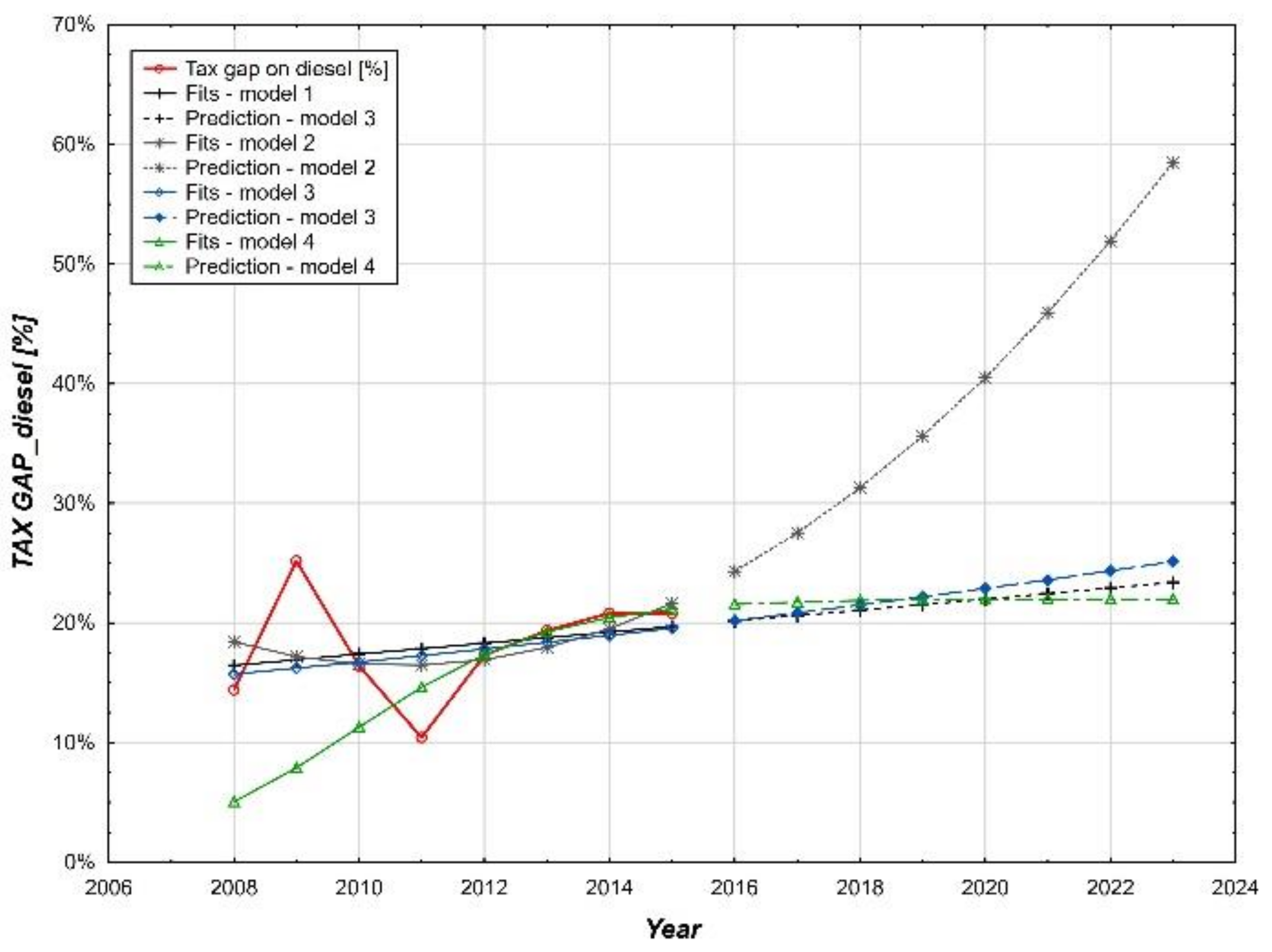

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chioran, D.; Valean, H. Design and Performance Evaluation of a Home Energy Management System for Power Saving. Energies 2021, 14, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaings, A.; Lhomme, W.; Trigui, R.; Bouscayrol, A. Energy Management of a Multi-Source Vehicle by λ-Control. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straková, J.; Rajiani, I.; Pártlová, P.; Váchal, J.; Dobrovič, J. Use of the Value Chain in the Process of Generating a Sustainable Business Strategy on the Example of Manufacturing and Industrial Enterprises in the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kot, S.; Štefko, R.; Dobrovič, J.; Rajnoha, R.; Váchal, J. The Main Performance and Effectiveness Factors of Sustainable Financial Administration Reform Using Multidimensional Statistical Tools. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nikonorova, A.V.; Stroev, P.V.; Morkovkin, D.E.; Bykova, O.N.; Isaichikova, N.I.; Kvak, A.A.; Skryabin, O.O. Development of Innovations Monitoring System and Its Implementation in Practice of Commercial Companies. AD ALTA J. Interdiscip. Res. 2019, 9, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Wulandari, D.; Utomo, S.H.; Narmaditya, B.S.; Kamaludin, M. Nexus between Inflation and Unemployment: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gódány, Z.; Machová, R.; Mura, L.; Zsigmond, T. Entrepreneurship Motivation in the 21st Century in Terms of Pull and Push Factors. TEM J. 2021, 10, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repnikova, V.M.; Bykova, O.N.; Skryabin, O.O.; Morkovkin, D.E.; Novak, L.V. Strategic Aspects of Innovative Development of Entrepreneurial Entities in Modern Conditions. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2019, 8, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Varyash, I.; Mikhaylov, A.; Moiseev, N.; Aleshin, K. Triple Bottom Line and Corporate Social Responsibility Performance Indicators for Russian Companies. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, L. The Economics of the Carbon Tax: Environmental Performance, Sustainable Energy, and Green Financial Behavior. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 2020, 12, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrower, K. Networked and Integrated Urban Technologies in Sustainable Smart Energy Systems. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 2020, 12, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, G. Sensor-based Big Data Applications and Computationally Networked Urbanism in Smart Energy Management Systems. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 2020, 12, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopenko, O.; Kornatowski, R. Features of Modern Strategic Market-Oriented Activity of Enterprises. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2018, 14, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Igaliyeva, L.; Niyazbekova, S.; Serikova, M.; Kenzhegaliyeva, Z.; Mussirov, G.; Zueva, A.; Tyurina, Y.G.; Maisigova, L.A. Towards Environmental Security Via Energy Efficiency: A Case Study. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 3488–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgonáš, J. Franchising in v 4 Countries; Akademie Krizového Řízení a Managementu: Uherské Hradiště, Czech Republic, 2020; p. 244. ISBN 978-80-906993-8-0. [Google Scholar]

- Orgonáš, J.; Paholková, B.; Drábik, P. Franchising Modern Form of Business for Small and Medium Sized Enterprises in the 21 st. century. Manag. Stud. 2020, 8, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ivančík, R.; Nečas, P. Towards Enhanced Security: Defence Expenditures in the Member States of the European Union. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2017, 6, 373–382. Available online: https://jssidoi.org/jssi/papers/papers/view/215 (accessed on 12 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Raczkowski, K. Measuring the Tax Gap in the European Economy. J. Econ. Manag. 2015, 21, 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Revenue, H.M.; Customs, H.M. Revenue and Customs 98 Measuring Tax gaps. 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/907122/Measuring_tax_gaps_2020_edition.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- US. Internal Revenue Service Press Release. IR-2005-38; 29 March 2005. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-prior/p17--2005.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Holmgren, R.D. The Internal Revenue Service Needs to Improve the Comprehensiveness, Accuracy, Reliability, and Timeliness of the Tax Gap Estimate; U.S. Department of the Treasury: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 1. Available online: https://www.treasury.gov/tigta/iereports/2013reports/2013IER008fr.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Rotz, W.; Murlow, J.; Falk, E. The 1995 Taxpayer Compliance Measurement Program (TCMP). Sample Redesign: A Case History. In Turning Administrative System into Information System; Jamerson, B., Alwey, W., Eds.; Internal Revenue Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; Available online: http://www.asasrms.org/Proceedings/papers/1994_119.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Dubin, J.A. The Causes and Consequences of Income Tax Noncompliance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4419-0907-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzhanova, G.; Mussirov, G.; Niyazbekova, S.; Ilyas, A.; Tyurina, Y.G.; Maisigova, L.A.; Troyanskaya, M.; Kunanbayeva, K. Demographic and migration processes of labor potential: A Case Study the Agricultural Sector of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 656–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopenko, O.; Omelyanenko, V. Intellectualization of the Phased Assessment and Use of the Potential for Internationalizing the Activity of Clusters of Cultural and Creative Industries of the Baltic Sea Regions. TEM J. 2020, 9, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseev, N.; Mikhaylov, A.; Varyash, I.; Saqib, A. Investigating the Relation of GDP Per Capita and Corruption Index. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydenko, V.; Kaźmierczyk, J.; Romashkina, G.F.; Żelichowska, E. Diversity of Employee Incentives from the Perspective of Banks Employees in Poland-Empirical Approach. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2017, 5, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaźmierczyk, J.; Chinalska, A. Flexible Forms of Employment, an Opportunity or a Curse for the Modern Economy? Case Study: Banks in Poland. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2018, 6, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, L. Pricing Carbon Pollution: Reducing Emissions or GDP Growth? Econ. Manag. Financial Mark. 2020, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Song, S.; Liao, Y. Supply Chain Coordination with a Risk-Averse Retailer and the Call Option Contract in the Presence of a Service Requirement. Mathematics 2021, 9, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Lin, B. Rethinking the choice of carbon tax and carbon trading in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 159, 120187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, C.; Huang, R. Impacts of Horizontal Integration on Social Welfare under the Interaction of Carbon Tax and Green Subsidies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 222, 107506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkaso, W.T.; Gren, I.-M. Road Fuel Demand and Regional Effects of Carbon Taxes in Sweden. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Ionescu, L.; Uță, C.; Hurloiu, I.; Andronie, M.; Dijmărescu, I. Environmentally Responsible Behavior and Sustainability Policy Adoption in Green Public Procurement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rout, C.; Paul, A.; Kumar, R.S.; Chakraborty, D.; Goswami, A. Cooperative sustainable supply chain for deteriorating item and imperfect production under different carbon emission regulations. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venmans, F.; Ellis, J.; Nachtigall, D. Carbon Pricing and Competitiveness: Are They at Odds? Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 1070–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulinska-Stangrecka, H.; Bagieńska, A. Investigating the Links of Interpersonal Trust in Telecommunications Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sopiah, S.; Kurniawa, D.T.; Nora, E.; Narmaditya, B.S. Does Talent Management Affect Employee Performance? The Moderating Role of Work Engagement. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulinska-Stangrecka, H.; Bagieńska, A. HR Practices for Supporting Interpersonal Trust and Its Consequences for Team Collaboration and Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazur, M.J.; Plumley, A.H.; Plumpley, A.H. Understanding the Tax Gap. Natl. Tax J. 2007, 60, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lešnik, T.; Jagrič, T.; Jagrič, V. VAT Gap Dependence and Fiscal Administration Measures. Naše Gospodarstvo Our Economy 2018, 64, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. Consumption Tax Trends. 2015. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/tax/consumption/consumption-tax-trends-19990979.htm (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- OECD. Tax Administration 2017: Comparative Information on OECD and Other Advanced and Emerging Economies; OECD: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://books.google.sk/books?id=v9U3DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA116&lpg=PA116&dq=32.%09OECD+ (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Zidkova, H. Determinants of VAT gap in EU, Prague Economic Papers. Prague Econ. Pap. 2014, 23, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. United Kingdom: Technical Assistance Report-Assessment HMRCs Tax Gap Analysis. 2013. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2013/cr13314.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- International Monetary Fund. Republic of Estonia: Revenue Administration Gap Analysis Program-The Value Added-Tax Gap. 2014. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2014/cr14133.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Center for Social and Economic Research (CASE); Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy and Analysis. Study to Quantify and Analyse the VAT Gap in the EU-27 Member States. 2013. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/docs/body/vat-gap.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Center for Social and Economic Research (CASE); Institute for Advanced Studies. Study and Reports on the VAT Gap in the EU-28. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/2016-09_vat-gap-report_final.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- HM Revenue and Customs. Methodological Annex for Measuring Tax Gaps. 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/249541/131009_MTG_2013_Annex.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Swedish National Tax Agency. Tax GAP MAP for Sweden. How Was It Created and How Can It Be Used? 2018. Available online: http://www.skatteverket.se/download/18.225c96e811ae46c823f800014872/Report_2008_1B.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- The Danish Customs and Tax Administration-SKAT. Business Sector Analysis. Compliance with Tax and VAT Rules by Businesses in Denmark. Tax Year 2006. Available online: https://skat.dk/skat.aspx?oid=2274194&lang=en&cid=ps-udenlandske-arbejdstagere-q2-go-gen-engelsk-260421&gclid=CjwKCAjw7diEBhB-EiwAskVi16wkCXKJ0DHeLUh718di_H0JQMwRs7KH8RICIS1ypOSe_Tz4e5P5IRoCEtwQAvD_BwE (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Tax Gap Project Group. The Concept of Tax Gaps, Report on VAT Gap Estimations. European Commission: Fiscalis Tax Gap Project Group (FPG/041). 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/docs/body/tgpg_report_en.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Gemmell, N.; Hasseldine, J. The Tax Gap: A Methodological Review. Adv. Tax. 2012, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenbichler, R.; Klucka, J.; Haviernikova, K.; Strelcova, S. Business Performance Management in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Slovak Republic: An Integrated Three- Phase-Framework for Implementation. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Durán-Cabré, J.M.; Moré, A.E.; Mas-Montserrat, M.; Salvadori, L. The Tax Gap as a Public Management Instrument: Application to wealth taxes. Appl. Econ. Anal. 2019, 27, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckon. Study to Quantify and Analyse the VAT Gap in the EU-25 Member States. 2009. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/resources/documents/taxation/tax_cooperation/combating_tax_fraud/reckon_report_sep2009.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Poniatowski, G.; Bonch-Osmolovskiy, M.; Durán-Cabré, J.M.; Esteller-Moré, A.; Śmietanka, A. Study and Reports on the VAT Gap in the EU-28 Member States; 2018 Final Report; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 978-92-76-19429-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, M. Targeting, Cascading, and Indirect Tax Design, International Monetary Fund. 2013. Working Paper; WP/13/57. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1357.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Babčák, V. Právo Európskej únie a boj proti podvodom v oblasti DPH. In Daňové Právo vs. Daňové Podvody a Daňové Úniky (Tax Law vs. Tax Frauds and Tax Evasion); Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika: Košice, Slovak, 2015; pp. 9–36. ISBN 978-80-8152-304-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pistone, P. The Meaning of Tax Avoidance and Aggressive Tax Planning in the European Union Tax Law: Some thoughts in connection with the reaction to such practices by the European Union. In Tax Avoidance Revisited in the EU BEPS Context; IBFD; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 73–100. ISBN 978-90-8722-422-6. [Google Scholar]

- Toder, E. What is the Tax Gap? Tax Notes 2007, 117, 367–378. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/46126/1001112-What-is-the-Tax-Gap-.PDF (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Gemmell, N.; Hasselidne, J. Taxpayers’ Behavioural Responses and Measures of Tax Compliance ‘Gaps’: A Critique and a New Measure. Fisc. Stud. 2014, 35, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velvizhi, V.; Billewar, S.R.; Londhe, G.; Kshirsagar, P.; Kumar, N. Big Data for Time Series and Trend Analysis of Poly Waste Management in India. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 37, 2607–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

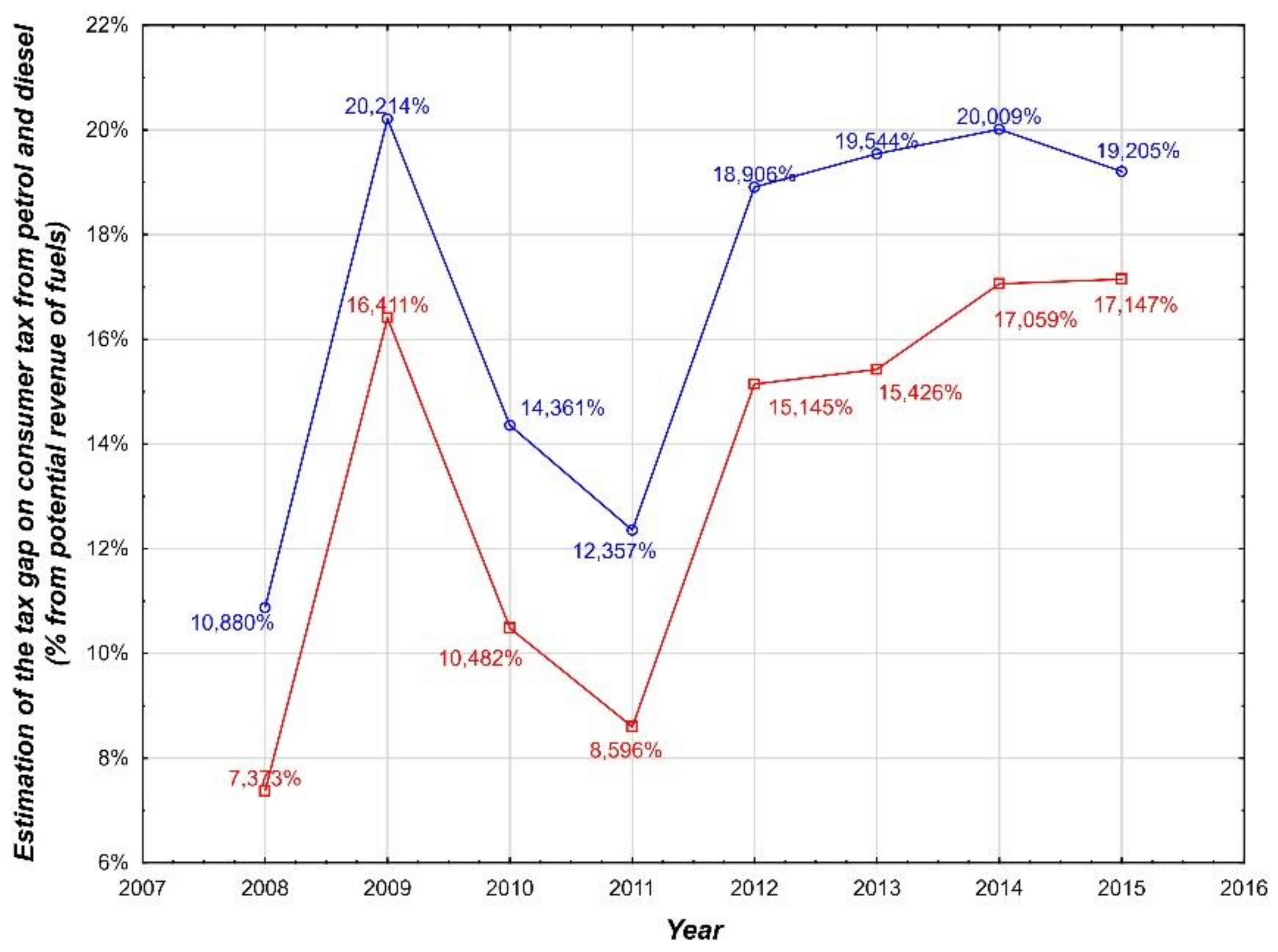

| In Millions EUR | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall consumption | 1217.5 | 1204.3 | 1067.6 | 1163.8 | 1210.7 | 1225.3 | 1289.6 | 1363.7 |

| Tax revenue | 1127.7 | 1006.7 | 955.7 | 1063.8 | 1027.3 | 1036.3 | 1069.6 | 1129.8 |

| Tax gap | 89.8 | 197.6 | 111.9 | 100.0 | 183.4 | 189.0 | 220.0 | 233.8 |

| Tax gap in % | 7.37% | 16.41% | 10.48% | 8.60% | 15.14% | 15.43% | 17.06% | 17.15% |

| Overall consumption of petrol | 484.1 | 445.2 | 446.0 | 445.4 | 444.2 | 419.4 | 414.6 | 410.5 |

| Tax revenue of petrol | 479.4 | 417.7 | 416.3 | 397.2 | 370.3 | 356.6 | 353.8 | 359.3 |

| Tax gap on petrol | 4.7 | 27.6 | 29.7 | 48.2 | 73.9 | 62.8 | 60.9 | 51.2 |

| Tax gap in % | 0.98% | 6.19% | 6.66% | 10.81% | 16.63% | 14.97% | 14.68% | 12.48% |

| Overall consumption of diesel | 733.4 | 759.1 | 621.7 | 718.4 | 766.4 | 806.0 | 874.9 | 953.2 |

| Tax revenue of diesel | 648.3 | 589.0 | 539.5 | 666.5 | 657.0 | 679.7 | 715.8 | 770.5 |

| Tax gap on diesel | 85.0 | 170.1 | 82.2 | 51.9 | 109.5 | 126.2 | 159.1 | 182.6 |

| Tax gap in % | 11.59% | 22.41% | 13.22% | 7.22% | 14.28% | 15.66% | 18.19% | 19.16% |

| In Millions Eur | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall consumption | 1265.4 | 1261.7 | 1116.0 | 1213.8 | 1266.8 | 1288.1 | 1337.1 | 1398.4 |

| Tax revenue | 1127.7 | 1006.7 | 955.7 | 1063.8 | 1027.3 | 1036.3 | 1069.6 | 1129.8 |

| Tax gap | 137.7 | 255.0 | 160.3 | 150.0 | 239.5 | 251.7 | 267.5 | 268.6 |

| Tax gap in v % | 10.88% | 20.21% | 14.36% | 12.36% | 18.91% | 19.54% | 20.01% | 19.20% |

| Overall consumption of petrol | 508.0 | 474.5 | 470.6 | 469.6 | 472.4 | 445.1 | 433.0 | 425.6 |

| Tax revenue of petrol | 479.4 | 417.7 | 416.3 | 397.2 | 370.3 | 356.6 | 353.8 | 359.3 |

| Tax gap on petrol | 28.6 | 56.8 | 54.4 | 72.3 | 102.0 | 88.6 | 79.3 | 66.3 |

| Tax gap in v % | 5.63% | 11.97% | 11.55% | 15.41% | 21.60% | 19.90% | 18.30% | 15.58% |

| Overall consumption of diesel | 757.4 | 787.2 | 645.4 | 744.2 | 794.4 | 842.9 | 904.1 | 972.8 |

| Tax revenue of diesel | 648.3 | 589.0 | 539.5 | 666.5 | 657.0 | 679.7 | 715.8 | 770.5 |

| Tax gap on diesel | 109.1 | 198.2 | 105.9 | 77.6 | 137.5 | 163.2 | 188.3 | 202.2 |

| Tax gap in v % | 14.40% | 25.18% | 16.41% | 10.43% | 17.30% | 19.36% | 20.83% | 20.79% |

| N | Mean | StDev | Standard Error Mean | 95% Lower Bound for μ | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0.1519 | 0.0388 | 0.0137 | 0.1260 | 0.14 | 0.446 |

| Variable | Model (5) | Model (6) | Model (7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.634% | 3.566% | 2.795% |

| Median | 2.397% | 6.308% | 2.961% |

| Minimum | −1.674% | −8.850% | 0.617% |

| Maximum | 3.125% | 9.292% | 4.507% |

| 25% Quartil | 0.469% | −0.832% | 1.712% |

| 75% Quartil | 2.943% | 8.567% | 3.945% |

| Range | 4.799% | 18.142% | 3.890% |

| Std.Dev. | 1.754% | 6.603% | 1.373% |

| St.Er. Mean | 0.620% | 2.334% | 0.486% |

| Shapiro-Wilk W | 0.846651 | 0.855053 | 0.960412 |

| Shapiro-Wilk p | 0.088094 | 0.107137 | 0.814016 |

| MAPE | 14.2218 | 6.8572 | 16.9092 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korauš, A.; Gombár, M.; Vagaská, A.; Šišulák, S.; Černák, F. Secondary Energy Sources and Their Optimization in the Context of the Tax Gap on Petrol and Diesel. Energies 2021, 14, 4121. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144121

Korauš A, Gombár M, Vagaská A, Šišulák S, Černák F. Secondary Energy Sources and Their Optimization in the Context of the Tax Gap on Petrol and Diesel. Energies. 2021; 14(14):4121. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144121

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorauš, Antonín, Miroslav Gombár, Alena Vagaská, Stanislav Šišulák, and Filip Černák. 2021. "Secondary Energy Sources and Their Optimization in the Context of the Tax Gap on Petrol and Diesel" Energies 14, no. 14: 4121. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144121

APA StyleKorauš, A., Gombár, M., Vagaská, A., Šišulák, S., & Černák, F. (2021). Secondary Energy Sources and Their Optimization in the Context of the Tax Gap on Petrol and Diesel. Energies, 14(14), 4121. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144121