Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of workflow followed for the systematic review.

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of workflow followed for the systematic review.

Figure 2.

Frequency of occurrence of each methodology per methodological stage in (a) onshore and (b) offshore wind energy research. Used methodologies in combination with other approaches in the relevant stages denoted with *.

Figure 2.

Frequency of occurrence of each methodology per methodological stage in (a) onshore and (b) offshore wind energy research. Used methodologies in combination with other approaches in the relevant stages denoted with *.

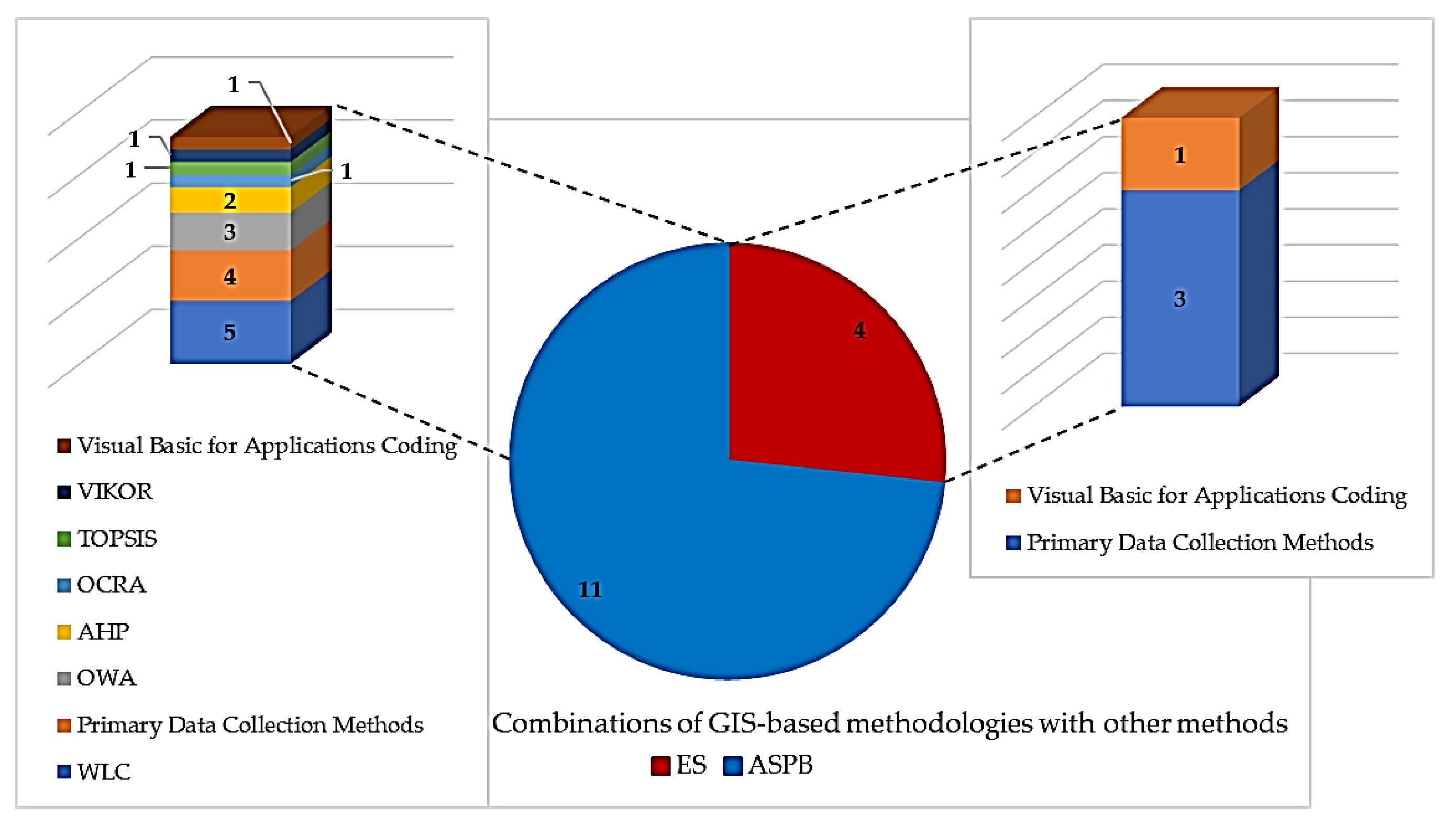

Figure 3.

Frequency of occurrence of combinations of GIS-based methodologies with other methods per methodological stage in onshore wind energy research.

Figure 3.

Frequency of occurrence of combinations of GIS-based methodologies with other methods per methodological stage in onshore wind energy research.

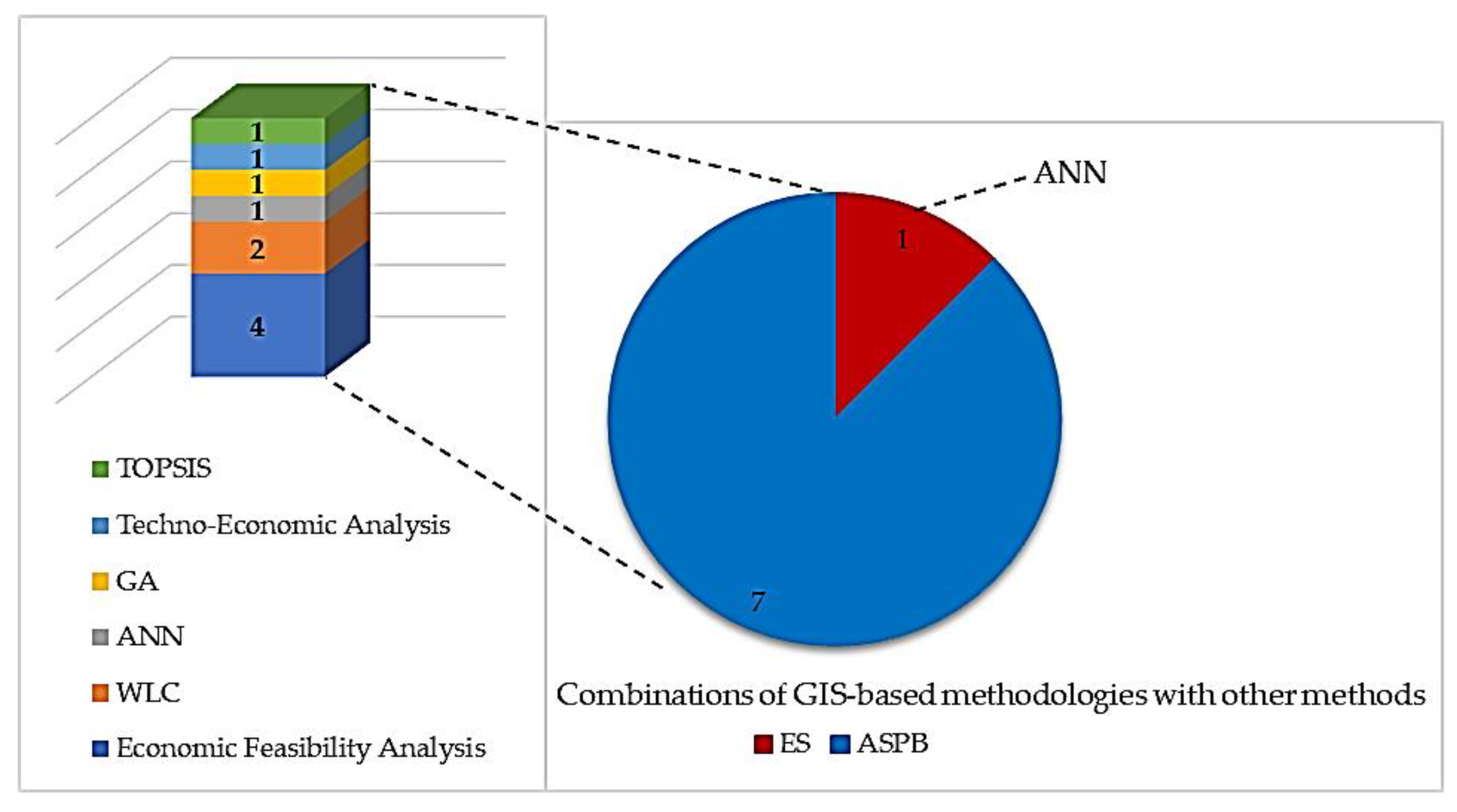

Figure 4.

Frequency of occurrence of combinations of GIS-based methodologies with other methods per methodological stage in offshore wind energy research.

Figure 4.

Frequency of occurrence of combinations of GIS-based methodologies with other methods per methodological stage in offshore wind energy research.

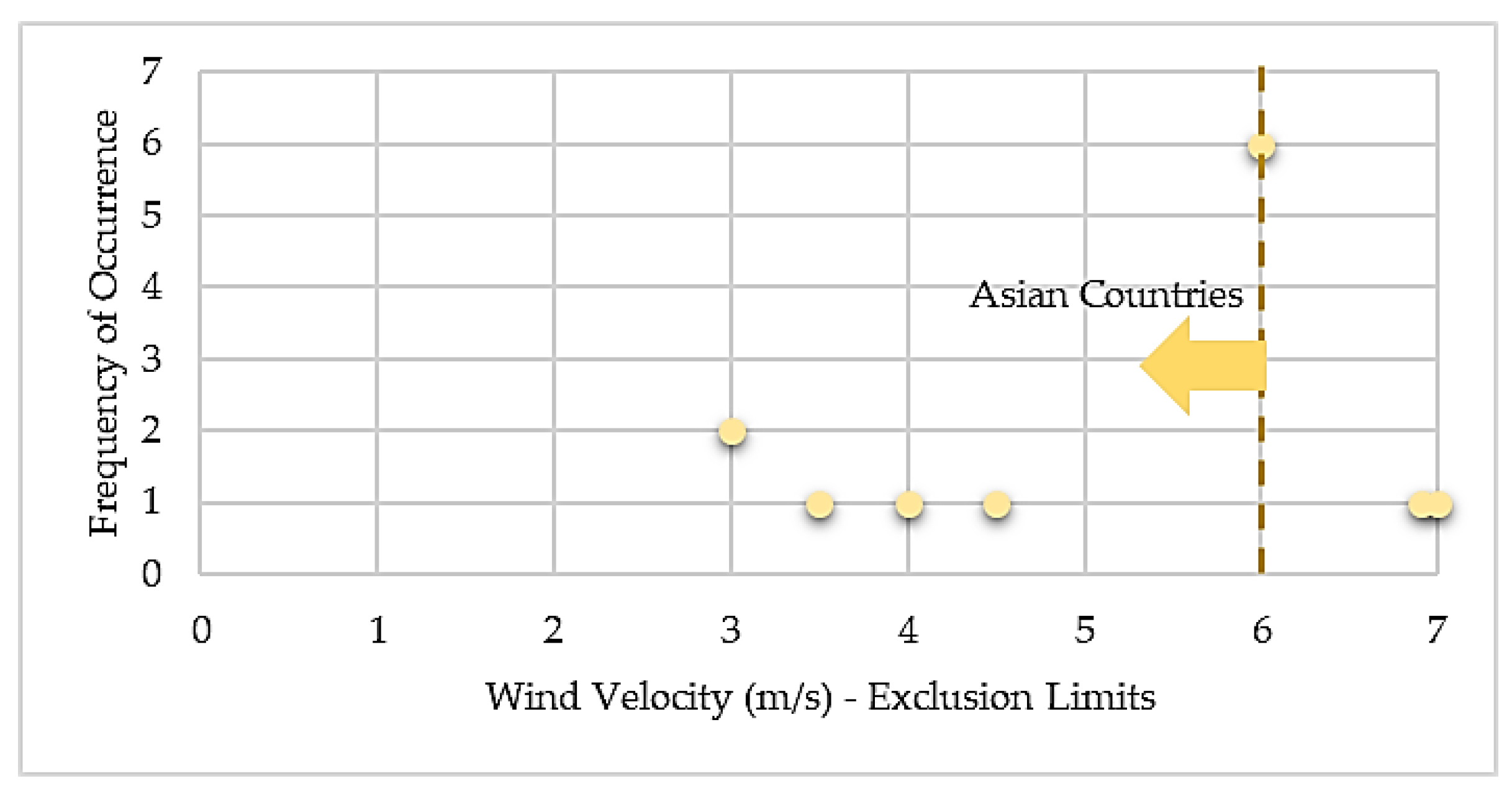

Figure 5.

Frequency of occurrence of exclusion limits applied for “wind velocity” criterion in the offshore wind energy siting studies.

Figure 5.

Frequency of occurrence of exclusion limits applied for “wind velocity” criterion in the offshore wind energy siting studies.

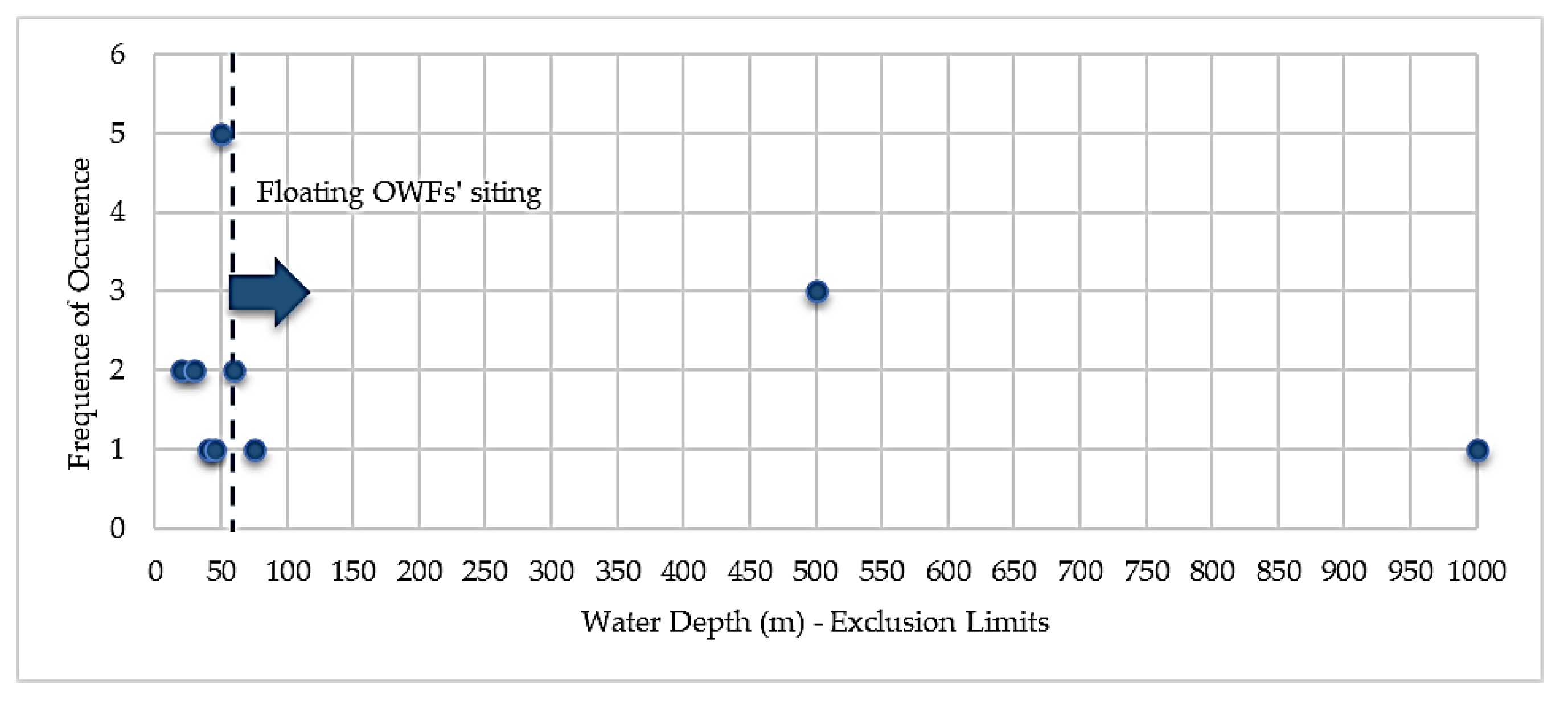

Figure 6.

Frequency of occurrence of exclusion limits applied for “water depth” criterion in the offshore wind energy siting studies.

Figure 6.

Frequency of occurrence of exclusion limits applied for “water depth” criterion in the offshore wind energy siting studies.

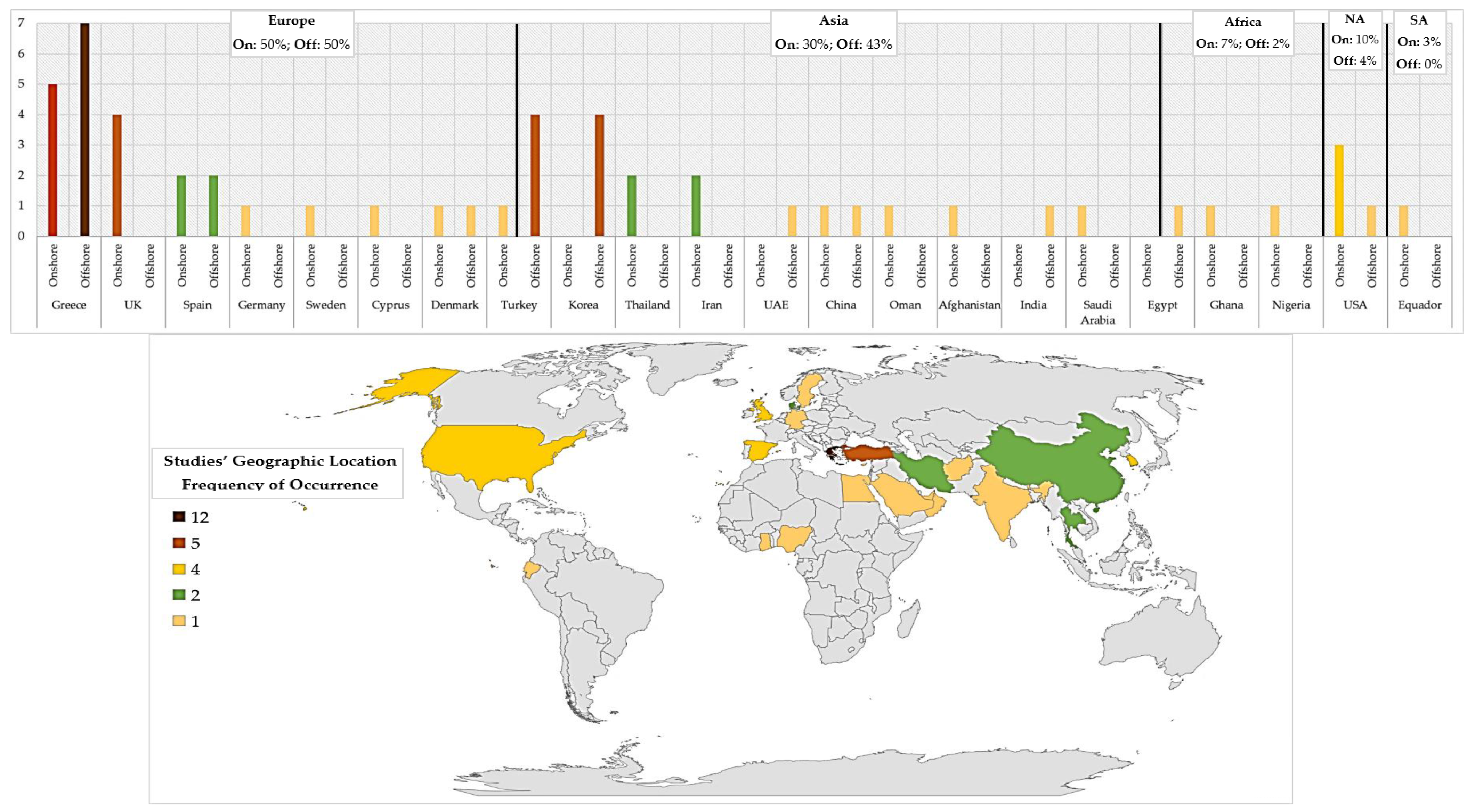

Figure 7.

Frequency of occurrence of geographic location of onshore and offshore WF siting studies on global, continental, and national scale.

Figure 7.

Frequency of occurrence of geographic location of onshore and offshore WF siting studies on global, continental, and national scale.

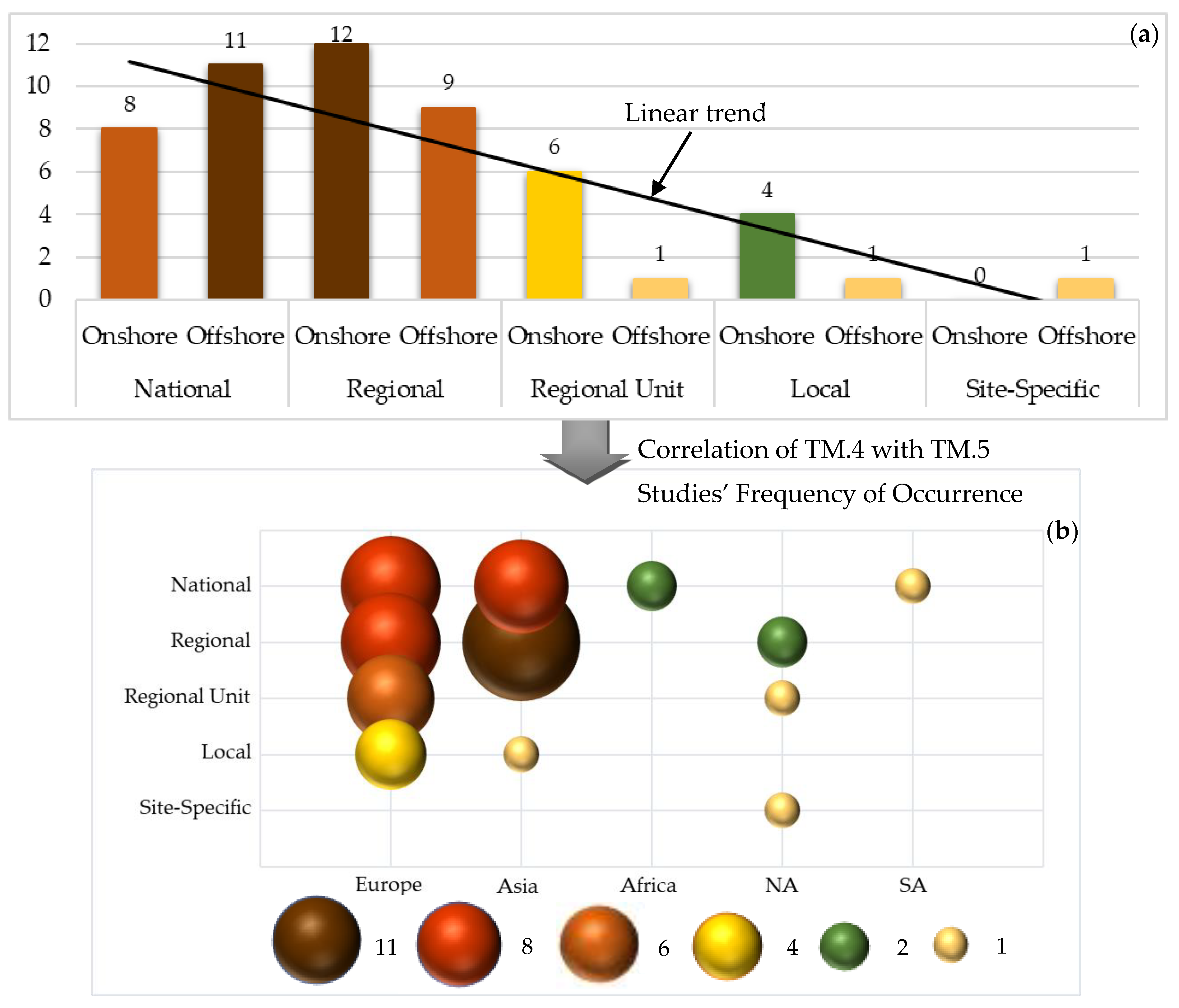

Figure 8.

Frequency of occurrence of (a) spatial planning scales and (b) their correlation with geographic locations of studies included in this systematic review.

Figure 8.

Frequency of occurrence of (a) spatial planning scales and (b) their correlation with geographic locations of studies included in this systematic review.

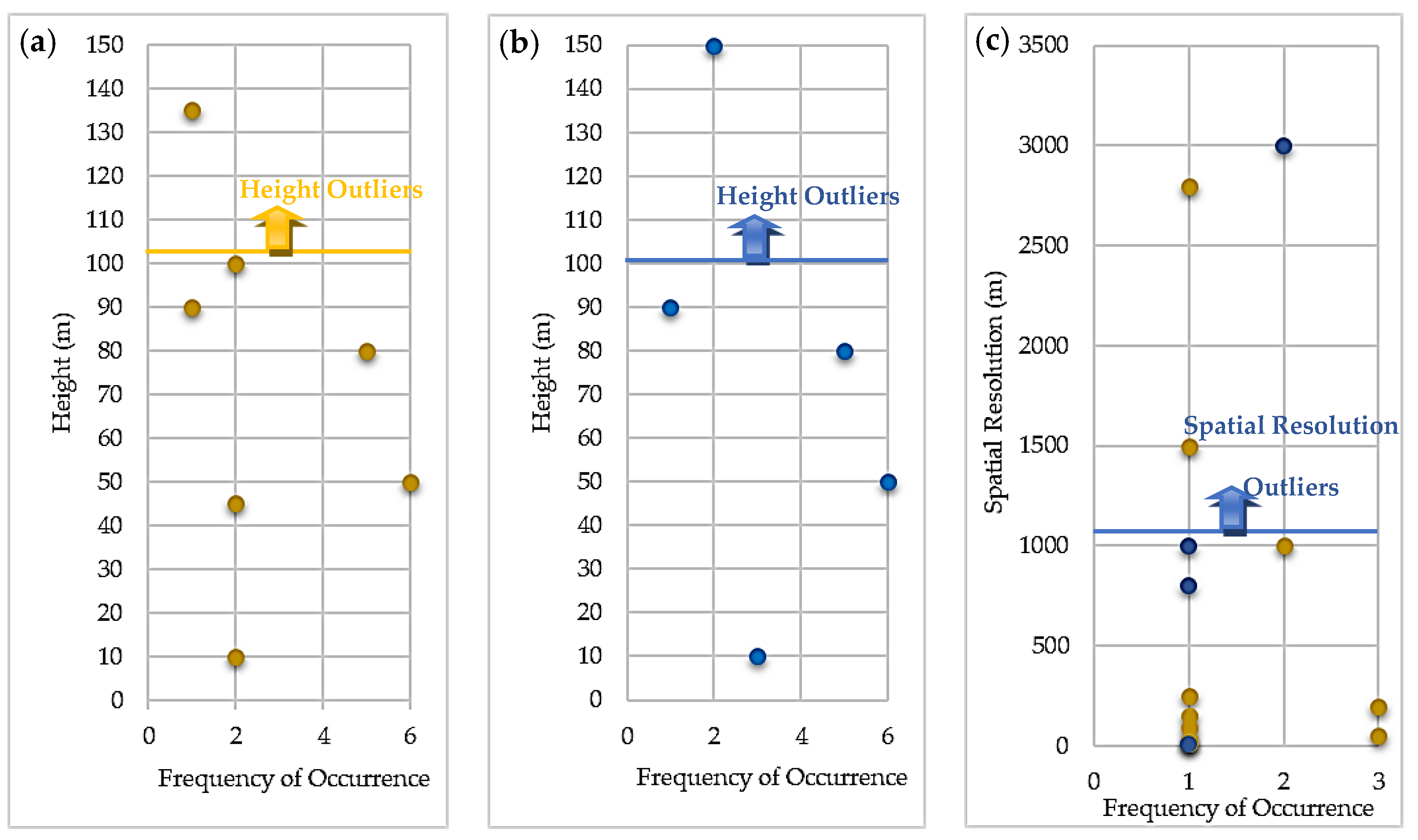

Figure 9.

Frequency of occurrence of (a) height of wind data on onshore WF siting studies, (b) height of wind data on offshore WF siting studies, and (c) spatial resolution of wind data on onshore and offshore WF siting studies.

Figure 9.

Frequency of occurrence of (a) height of wind data on onshore WF siting studies, (b) height of wind data on offshore WF siting studies, and (c) spatial resolution of wind data on onshore and offshore WF siting studies.

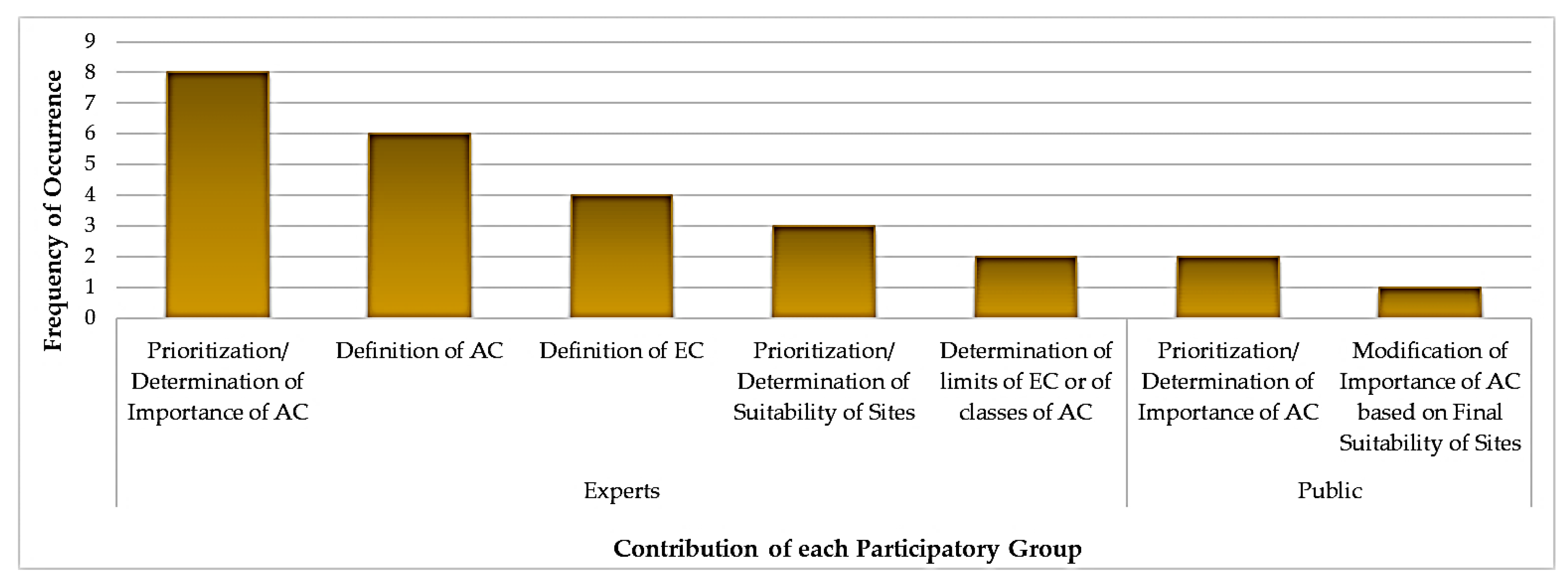

Figure 10.

Type and frequency of occurrence of contributions of each participatory group on onshore wind energy siting applications.

Figure 10.

Type and frequency of occurrence of contributions of each participatory group on onshore wind energy siting applications.

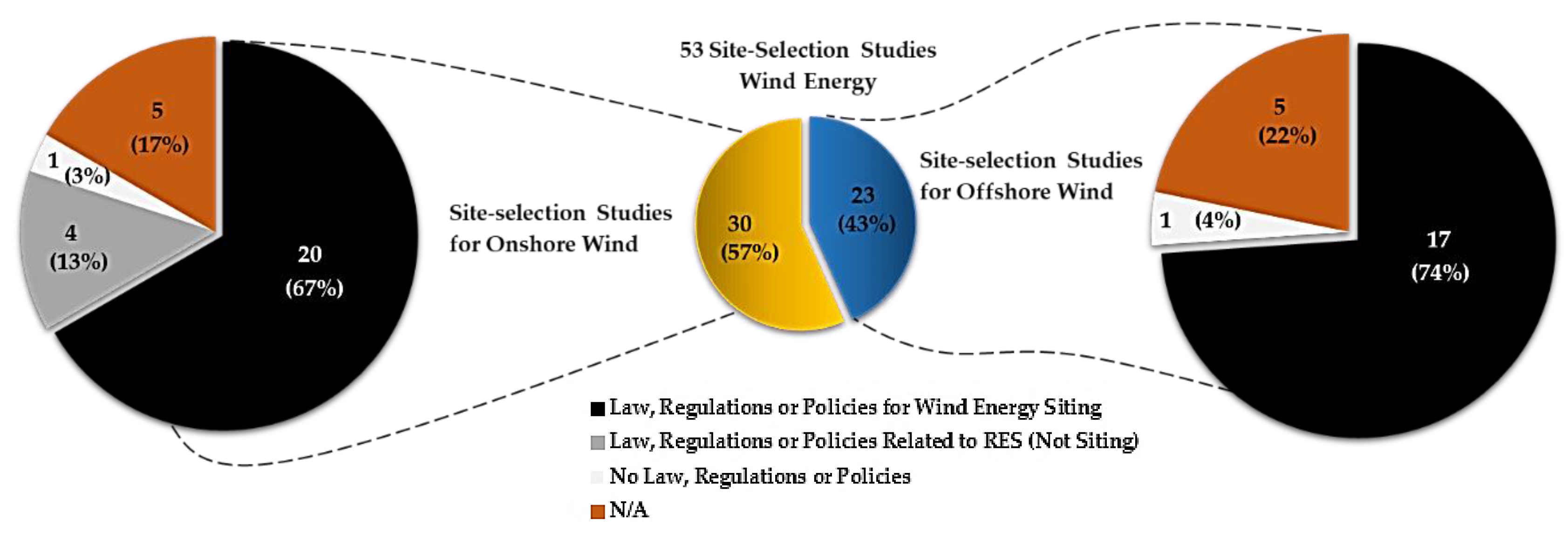

Figure 11.

Frequency of occurrence of laws, regulations, or policies that were considered for WF siting and development.

Figure 11.

Frequency of occurrence of laws, regulations, or policies that were considered for WF siting and development.

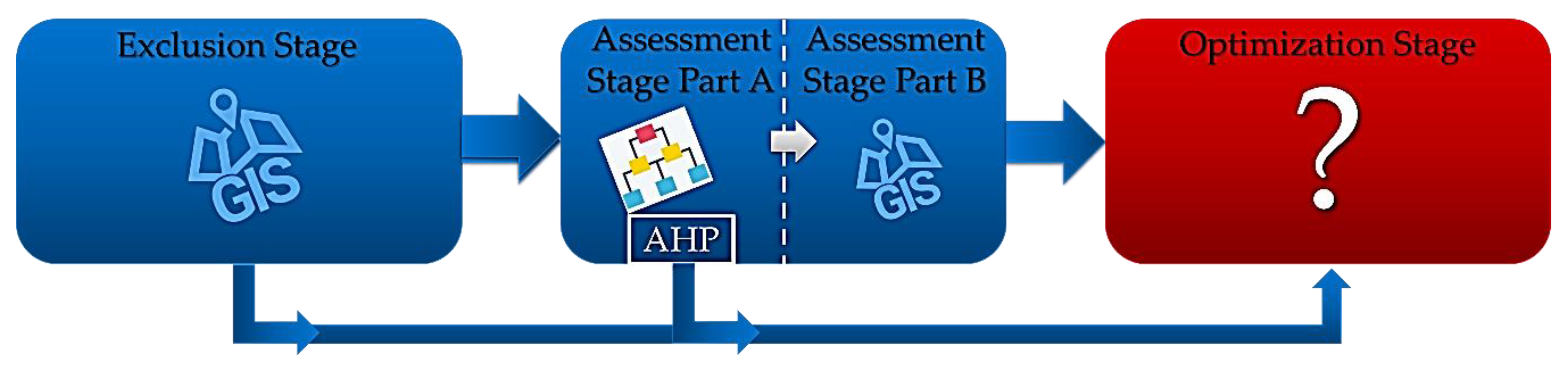

Figure 12.

Frequently used methodologies and absence of a clear optimization stage.

Figure 12.

Frequently used methodologies and absence of a clear optimization stage.

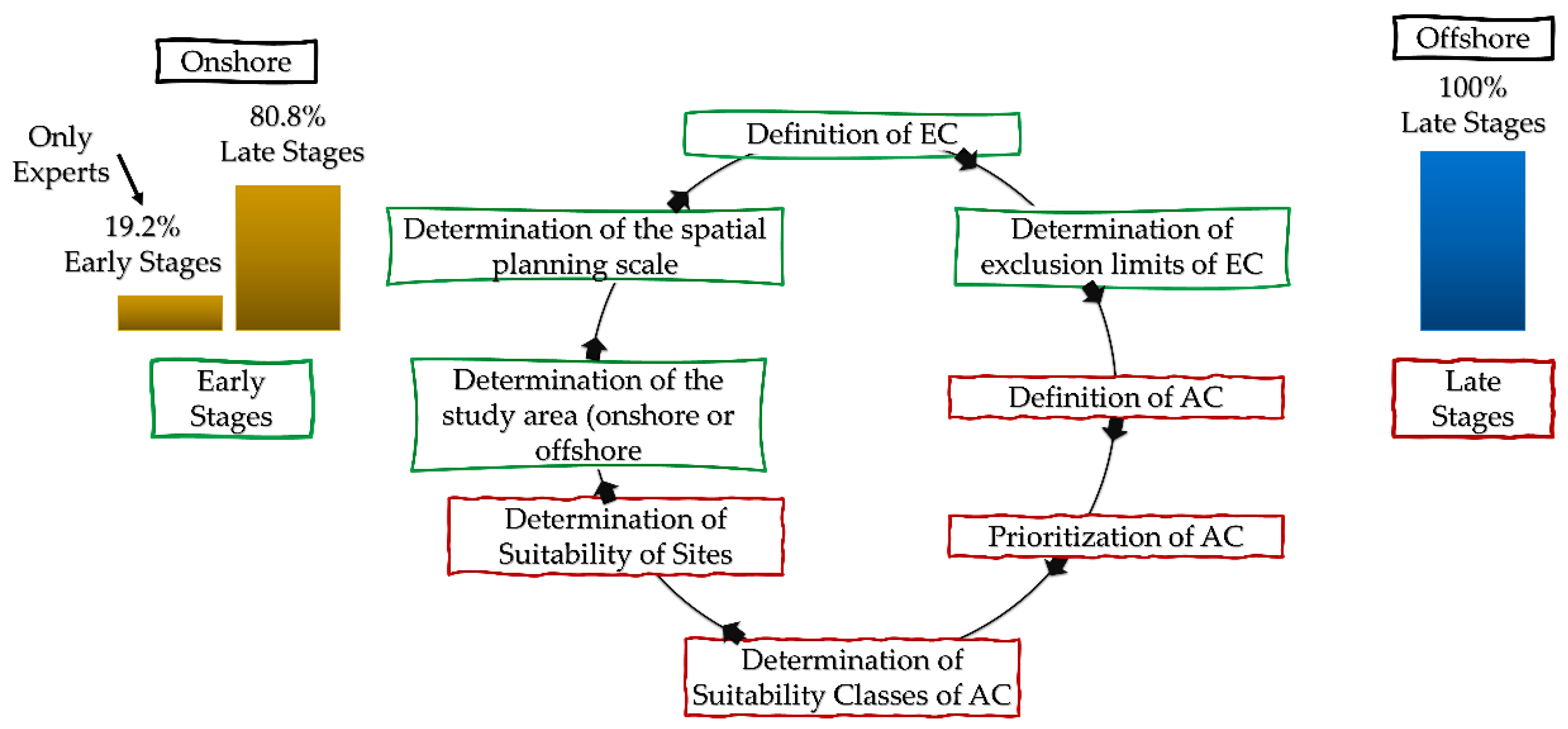

Figure 13.

Spatial energy planning as a circular process, and lack of involvement of participatory groups in early stages of the process.

Figure 13.

Spatial energy planning as a circular process, and lack of involvement of participatory groups in early stages of the process.

Table 1.

Datasets produced in accordance with selected thematic modules and data type. Note: EC, exclusion criteria; AC, assessment criteria; WF, wind farm.

Table 1.

Datasets produced in accordance with selected thematic modules and data type. Note: EC, exclusion criteria; AC, assessment criteria; WF, wind farm.

| No. | Name of Thematic Module | Data Parameter | Data Type |

|---|

| TM.1 | Site-selection methodologies | Frequency of occurrence per methodological stage | Quantitative |

| Successful combinations between site-selection methodologies | Qualitative, Quantitative |

| TM.2 | EC | EC type | Qualitative |

| EC number | Quantitative |

| Frequency of occurrence of EC | Quantitative |

| Exclusion limits (mean, min, max, and predominant values) | Quantitative |

| TM.3 | AC | AC type | Qualitative |

| AC number | Quantitative |

| Frequency of occurrence of AC | Quantitative |

| Determination of importance of AC based on their mean weights and priority position | Quantitative |

| Optimal AC values | Quantitative |

| Poor AC values | Quantitative |

| TM.4 | Geographic location | Frequency of occurrence on global, continental, and national scale | Quantitative |

| TM.5 | Spatial planning scale | Frequency of occurrence | Quantitative |

| Correlation with studies’ geographic locations | Qualitative, Quantitative |

| TM.6 | Wind resource analysis | Methodology | Qualitative, Quantitative |

| Height of wind analysis | Quantitative |

| Period of time of wind analysis | Quantitative |

| Spatial resolution of wind data | Quantitative |

| TM.7 | Sensitivity analysis | Type of “what-if” scenarios | Qualitative |

| Number of “what-if” scenarios | Quantitative |

| TM.8 | Participatory planning | Methodology | Qualitative, Quantitative |

| Participatory group | Qualitative |

| Number of participants | Quantitative |

| Contribution of each participant and participation | Qualitative, Quantitative |

| TM.9 | Laws, regulations, or policies related to WF siting | Type of legislative frameworks and correlation with geographic locations | Qualitative, Quantitative |

| Frequency of occurrence | Quantitative |

| TM.10 | Suitability index and classifications | Types of classification in numeric and linguistic terms | Qualitative, Quantitative |

| TM.11 | Micro-siting configuration of wind turbines | Layout and wind turbine capacity | Qualitative, Quantitative |

Table 2.

Type of land exclusion criteria (LEC) identified in studies included in this systematic review in accordance with their frequency of occurrence, mean, min, max, and predominant value(s).

Table 2.

Type of land exclusion criteria (LEC) identified in studies included in this systematic review in accordance with their frequency of occurrence, mean, min, max, and predominant value(s).

| No. | Description | Frequency of Occurrence | Mean Value | Min/Max Value | Predominant Value(s) |

|---|

| LEC 1 | Urban and residential areas | 28 | 1125 m | 0/3000 m | 500 m |

| LEC 2 | Protected environmental areas | 24 | 550 m | 0/2000 m | 0 m |

| LEC 3 (lower limits) | Proximity to road network | 23 | 220 m | 0/500 m | 500 m |

| LEC 3 (upper limits) | 6335 m | 2000/10,000 m | N/a upper limit (10,000 m) |

| LEC 4 | Civil/military aviation areas | 22 | 4060 m | 0/17,000 m | 2500 and 3000 m |

| LEC 5 (upper limits) | Slope of terrain | 19 | 18.65% | 10/57.7% | 10% |

| LEC 6 | Water surfaces | 17 | 475 m | 0/4000 m | 100 and 400 m |

| LEC 7 (lower limits) | Proximity to high-voltage electricity grid | 16 | 160 m | 50/250 m | 100 and 250 m |

| LEC 7 (upper limits) | 7400 m | 2000/10,000 m | N/a upper limit (10,000 m) |

| LEC 8 | Bird habitats and migration corridors | 16 | 560 m | 0/3000 m | 0 m |

| LEC 9 | Land cover | 15 | DO 1 | DO 1/DO 1 | DO 1 |

| LEC 10 | Archeological, historical, and cultural heritage sites | 14 | 990 m | 0/3000 m | 0, 500, and 1000 m |

| LEC 11 | Wind velocity | 12 | 5.20 m/s | 4/6.5 m/s | 5 m/s |

| LEC 12 | Other land uses | 12 | DO 1 | DO 1/DO 1 | DO 1 |

| LEC 13 | Agricultural land | 9 | 85 m | 0/500 m | 0 m |

| LEC 14 | Protected landscapes | 7 | 855 m | 0/2000 m | 1000 m |

| LEC 15 | Elevation | 7 | 1315 m | 200/2000 m | 2000 m |

| LEC 16 | Military zones | 6 | 1690 m | 0/10,000 m | 0 m |

| LEC 17 | Touristic zones | 6 | 750 m | 0/1000 m | 1000 m |

| LEC 18 | Religious sites | 6 | 465 m | 300/500 m | 500 m |

| LEC 19 | Railway network | 6 | 142 m | 0/300 m | 100 m |

| LEC 20 | Solitary dwellings | 6 | 500 m | 500/500 m | 500 m |

| LEC 21 | Areas with possibility of electromagnetic interference | 5 | 550 m | 0/1000 m | 600 m |

| LEC 22 | Farm minimum required area | 5 | 1.65 km2 | 0.005/4 km2 | 4 km2 |

| LEC 23 | Mineral extraction sites/quarrying activities | 4 | 375 m | 0/500 m | 500 m |

| LEC 24 | Wind power density | 2 | 225 W/m2 | 200/250 W/m2 | - |

| LEC 25 | Existing renewable energy systems | 2 | - | 2.5Drotor/5Drotor | - |

| LEC 26 | Hazard of natural phenomena | 1 | - | -/- | - |

| LEC 27 | Underground cables | 1 | 300 m | 300/300 m | 300 m |

| LEC 28 | Land aspect | 1 | - | -/- | - |

Table 3.

Type of marine exclusion criteria (MEC) identified in studies included in this systematic review in accordance with their frequency of occurrence, mean, min, max, and predominant value(s).

Table 3.

Type of marine exclusion criteria (MEC) identified in studies included in this systematic review in accordance with their frequency of occurrence, mean, min, max, and predominant value(s).

| No. | Description | Frequency of Occurrence | Mean Value | Min/Max Value | Predominant Value(s) |

|---|

| MEC 1 (lower limits) | Water depth | 18 | 33.5 m | 5/62 m | - |

| MEC 1 (upper limits) | 175 m | 20/1000 m | 50 m |

| MEC 2 | Protected environmental areas | 18 | 780 m | 0/3000 m | 0 m |

| MEC 3 | Verified shipping routes | 14 | 1205 m | 0/4800 m | 0 m |

| MEC 4 | Wind velocity | 13 | 5.2 m/s | 3/7 m/s | 6 m/s |

| MEC 5 | Military zones | 11 | 45.45 m | 0/500 m | 0 m |

| MEC 6 | Landscape protection/visual and acoustic disturbance | 10 | 7335 m | 1000/25,000 m | 5000 m |

| MEC 7 | Bird habitats and migration corridors | 10 | 1050 m | 0/3000 m | 0 m |

| MEC 8 | Pipelines and underwater cables | 8 | 160 m | 0/500 m | 0 m |

| MEC 9 (upper limits) | Proximity to local ports | 7 | 82,145 m | 20,000/200,000 m | 100,000 m |

| MEC 10 | Geographic boundaries | 7 | - | TW 1/EEZ 1 | TW 1 |

| MEC 11 | Other marine uses | 7 | DO 2 | DO 2/DO 2 | DO 2 |

| MEC 12 | Fishing areas | 6 | 105 m | 0/500 m | 0 m |

| MEC 13 (lower limits) | Proximity to high-voltage electricity grid | 5 | 1000 m | 1000/1000 m | 1000 m |

| MEC 13 (upper limits) | 60,000 m | 20,000/100,000 m | - |

| MEC 14 | Urban and residential areas | 4 | 1250 m | 1000/1500 m | - |

| MEC 15 | Seismic hazard | 3 | - | -/- | HSHZ 3 |

| MEC 16 | Civil/military aviation areas | 3 | N/a | N/a | N/a |

| MEC 17 | Wind power density | 2 | 285 W/m2 | 200/367 W/m2 | - |

| MEC 18 | Farm minimum required area | 2 | 25 km2 | 25/25 km2 | 25 km2 |

| MEC 19 | Seabed morphology | 1 | - | -/- | Rocky areas |

Table 4.

Type of land assessment criteria (LAC) identified in studies included in this systematic review in accordance with their frequency of occurrence, mean weight (i.e., relative importance), priority position, and their optimal and poor value(s).

Table 4.

Type of land assessment criteria (LAC) identified in studies included in this systematic review in accordance with their frequency of occurrence, mean weight (i.e., relative importance), priority position, and their optimal and poor value(s).

| LAC | Description | Frequency of Occurrence | Mean Weight | Priority Position | Mean Optimal Value(s) | Mean Poor Value(s) |

|---|

| LAC 1 | Wind velocity | 22 | 37% | 1° (94.45%) | ≥8.47 m/s | ≤5.20 m/s |

| LAC 2 | Proximity to road network | 22 | 12% | 3° and last (35%) | ≤955 m | ≥6315 m |

| LAC 3 | Proximity to high-voltage electricity grid | 20 | 13% | 2° (37.5%) | ≤1495 m | ≥9380 m |

| LAC 4 | Urban and residential areas | 17 | 12% | 3° (35.70%) | ≥4880 m | ≤2010 m |

| LAC 5 | Slope of terrain | 15 | 10% | 6° and penultimate (23.1%) | ≤3.91% | ≥22.90% |

| LAC 6 | Protected environmental areas | 11 | 10% | 2° and last (50%) | ≥1700 m | ≤1060 m |

| LAC 7 | Land cover | 9 | 10% | 2° (37.50%) | No 1 and/or 2≥1335 m | Yes 1 and/or 2≤935 m |

| LAC 8 | Civil/military aviation areas | 8 | 6% | Last (50%) | ≥13,500 m | ≤4915 m |

| LAC 9 | Other land uses | 7 | 18.85% | 2° (33.33%) | Arid land 3 | N/a 3 |

| LAC 10 | Wind power density | 5 | 25.15% | 1° (75%) | ≥350 W/m2 | ≤185 W/m2 |

| LAC 11 | Archeological/historical and cultural heritage sites | 5 | 8.10% | 3° (75%) | ≥1800 m | ≤800 m |

| LAC 12 | Elevation | 5 | 7.50% | N/a | ≤30 m | ≥350 m |

| LAC 13 | Bird habitats and migration corridors | 5 | 5.95% | Last (100%) | ≥12,000 m | ≤2375 m |

| LAC 14 | Landscape protection | 5 | 8% | N/a | ≥4000 m | ≤1500 m |

| LAC 15 | Water surfaces | 4 | 5.12% | N/a | ≥635 m | ≤275 m |

| LAC 16 | Visual impact | 4 | 5.25% | 5° (50%) | N/a | N/a |

| LAC 17 | Areas with possibility of electromagnetic interference | 3 | N/a | N/a | ≥2750 m | ≤700 m |

| LAC 18 | Agricultural land | 3 | 4% | N/a | Low/no 4 and/or >2000 m | High 4 and/or ≤1000 m |

| LAC 19 | Population density | 2 | 10.04% | N/a | N/a | N/a |

| LAC 20 | Electricity demand/consumption | 2 | 12.85% | N/a | >154,440 MWh | ≤3620 MWh |

| LAC 21 | Touristic zones | 2 | 6.40% | N/a | ≥2200 m | ≤800 m |

| LAC 22 | Religious sites | 2 | N/a | N/a | >500 m | ≤400 m |

| LAC 23 | Proximity to coastline | 2 | N/a | N/a | >3000 m | ≤100 m |

| LAC 24 | Farm required area | 2 | 20.58% | N/a | ≥3,500,000 m2 | <2,505,000 m2 |

Table 5.

Type of marine assessment criteria (MAC) identified in studies included in this systematic review in accordance with their frequency of occurrence, mean weight (i.e., relative importance), priority position, and their optimal and poor value(s).

Table 5.

Type of marine assessment criteria (MAC) identified in studies included in this systematic review in accordance with their frequency of occurrence, mean weight (i.e., relative importance), priority position, and their optimal and poor value(s).

| No. | Description | Frequency of Occurrence | Mean Weight | Priority Position | Mean Optimal Value(s) | Mean Poor Value(s) |

|---|

| MAC 1 | Wind velocity | 12 | 28.90% | 1° (77.80%) | ≥9.42 m/s | ≤6.43 m/s |

| MAC 2 | Water depth | 9 | 18.35% | 2° (37.50%) | ≤42.5 m | ≥182 m |

| MAC 3 | Proximity to high-voltage electricity grid | 9 | 14.85% | 3° and 5° (25%) | ≤18,375 m | ≥135,845 m |

| MAC 4 | Protected environmental areas | 8 | 11% | Last (42.90%) | ≥20,835 m | ≤6700 m |

| MAC 5 | Proximity to local ports | 6 | 10% | N/a | ≤29,375 m | ≥63,000 m |

| MAC 6 | Verified shipping routes | 6 | 6.50% | 3° and last (40%) | >3704 m or low SD 1 | ≤1852 m or high SD 1 |

| MAC 7 | Landscape protection/visual and acoustic disturbance | 5 | 11.80% | Penultimate (50%) | ≥15,555 m | ≤2520 m |

| MAC 8 | Wind energy potential | 4 | N/a | N/a | >166,029 MWh/year and/or ≥770 MW | ≤105,232 MWh/year and/or ≤20 MW |

| MAC 9 | Fishing habitats/activity and marine species habitats | 4 | 5.70% | N/a | N/a | N/a |

| MAC 10 | Wind power density | 3 | N/a | N/a | ≥675 W/m2 | ≤45 W/m2 |

| MAC 11 | Military exercise areas | 3 | 6% | N/a | >60,000 m | ≤20,000 m |

| MAC 12 | Population served | 3 | 13.55% | N/a | N/a | N/a |

| MAC 13 | Distance from the shore (for economic purposes) | 3 | 9% | 3° (67%) | ≤25,750 m | ≥200,000 m |

| MAC 14 | Bird habitats and migration corridors | 2 | N/a | N/a | N/a | N/a |

| MAC 15 | Total investment cost | 2 | 15.60% | 2° (100%) | N/a | N/a |

| MAC 16 | Soil status/seabed geology | 2 | 7% | Penultimate (100%) | Medium-to-coarse sandy soil and 5 m | N/a and 21 m |

| MAC 17 | Underwater cables and pipelines | 2 | N/a | N/a | N/a | N/a |

Table 6.

Methodologies employed for wind resource analysis and related characteristics. Note: WAsP, Wind Atlas Analysis and Application Program; IDW, inverse distance weighting; ANN, artificial neural network; GA, genetic algorithm; TIN, triangular irregular network.

Table 6.

Methodologies employed for wind resource analysis and related characteristics. Note: WAsP, Wind Atlas Analysis and Application Program; IDW, inverse distance weighting; ANN, artificial neural network; GA, genetic algorithm; TIN, triangular irregular network.

| Location | Methodology | Frequency of Occurrence | Software/Technique (Predominant) | Frequency of Occurrence |

|---|

| Onshore | N/a | 6 | - | - |

| None | 1 | - | - |

| Climate modelling | 5 | WAsP | 2 |

| GIS interpolation analysis | 2 | IDW | 2 |

| GIS analysis (other) | 16 | ArcGIS | 13 |

| Offshore | N/a | 5 | - | - |

| None | 3 | - | - |

| Climate modeling | 2 | WAsP and ANN-GA | 1 and 1 |

| GIS interpolation analysis | 3 | TIN | 2 |

| GIS analysis (other) | 10 | ArcGIS and GIS-No name | 4 and 4 |

Table 7.

Height and period of time of wind resource analysis.

Table 7.

Height and period of time of wind resource analysis.

| Location | Parameter of Wind Analysis | Min Value | Max Value | Mean Value | Predominant Value(s) |

|---|

| Onshore | Height (m) | 10 | 135 | 65 | 50 |

| Period of time (year(s)) | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| Offshore | Height (m) | 10 | 150 | 65 | 50 |

| Period of time (year(s)) | 1 | 20 | 8.5 | 10 |

Table 8.

Type of sensitivity analysis applied on site-selection applications of onshore wind energy research. Note: AHP, analytic hierarchy process; VBAC, visual basic for application coding; BC, borda count.

Table 8.

Type of sensitivity analysis applied on site-selection applications of onshore wind energy research. Note: AHP, analytic hierarchy process; VBAC, visual basic for application coding; BC, borda count.

| Study | Number of Scenarios | Method | Equal Weights Scenario | Environmental/Social Scenario | Technical/Economic Scenario |

|---|

| [8] | 1 | AHP | ✓ | N/a | N/a |

| [2] | 3 | AHP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [26] | 3 | VBAC and BC | N/a | ✓ | ✓ |

| [29] | 2 | AHP | ✓ | ✓ | N/a |

| [4] | 2 | AHP | ✓ | N/a | ✓ |

| [5] | 4 | AHP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [37] | 3 | AHP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mean Value | 2.57 | - | - | - | - |

| Predominant Value | 3 | - | - | - | - |

Table 9.

Type of sensitivity analysis applied to site-selection applications of offshore wind energy research.

Table 9.

Type of sensitivity analysis applied to site-selection applications of offshore wind energy research.

| Study | Number of Scenarios | Method | Equal Weights Scenario | Environmental/Social Scenario | Technical/Economic Scenario |

|---|

| [48] | 4 | AHP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [52] | 2 | AHP | ✓ | N/a | ✓ |

| [15] | 1 | AHP | N/a | ✓ | N/a |

| [57] | 4 | AHP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mean Value | 2.75 | - | - | - | - |

| Predominant Value | 4 | - | - | - | - |

Table 10.

Frequency of occurrence of each involved participatory group and employed methodologies for their incorporation within the site-selection process. Note: BOCR, benefits opportunities costs and risks; BC, borda count; PGIS, participatory GIS.

Table 10.

Frequency of occurrence of each involved participatory group and employed methodologies for their incorporation within the site-selection process. Note: BOCR, benefits opportunities costs and risks; BC, borda count; PGIS, participatory GIS.

| Location | Participatory Group | Frequency of Occurrence | Methodology | Frequency of Occurrence |

|---|

| Onshore | Experts | 11 | AHP | 8 |

| Primary data-collection methods | 6 |

| BOCR | 1 |

| Weighted least-squares method | 1 |

| N/a | 2 |

| Public | 2 | BC | 1 |

| Visual basic for application coding | 1 |

| Web-based PGIS | 1 |

| Offshore | Experts | 3 | Primary data-collection methods | 2 |

| AHP | 1 |

| N/a | 1 |

| Any type of participant (hypothetical case study) | 1 | Web-based PGIS | 1 |

| BC | 1 |

Table 11.

Frequency of occurrence of each type of suitability index (SI) employed in the site-selection process.

Table 11.

Frequency of occurrence of each type of suitability index (SI) employed in the site-selection process.

| Location | SI | Frequency of Occurrence |

|---|

| Onshore | From 0 to 1: (0, 1) | 13 |

| From 1 to 10: (1, 10) | 3 |

| From 1 to 100: (1, 100) | 3 |

| From 1 to 6: (1, 6) | 1 |

| From 1 to 3: (1, 3) | 1 |

| From 1 to 5: (1, 5) | 1 |

| From 1 to 4: (1, 4) | 1 |

| From 0 to 3: (0, 3) | 1 |

| From 0 to 9: (0, 9) | 1 |

| N/a | 5 |

| Offshore | From 0 to 1: (0, 1) | 3 |

| From 1 to 110: (1, 110) | 1 |

| From 0 to 10: (0, 10) | 1 |

| From 1 to 9: (1, 9) | 1 |

| From 6 to 9: (6, 9) | 1 |

| From 1 to 5: (1, 5) | 1 |

| N/a | 15 |

Table 12.

Micro-siting configuration of wind turbines in onshore and offshore WF siting studies. Note: Drotor, rotor diameter; MW, megawatt.

Table 12.

Micro-siting configuration of wind turbines in onshore and offshore WF siting studies. Note: Drotor, rotor diameter; MW, megawatt.

| Location | Study | Dx | Dy | Wind Turbine Capacity |

|---|

| Onshore | [30] | 10Drotor | 10Drotor | N/a |

| [31] | 5Drotor | 3Drotor | N/a |

| [32] | 10Drotor | 5Drotor | 3 MW |

| [5] | 3Drotor | 3Drotor | 0.850 MW |

| [41] | N/a | N/a | 2 MW |

| Offshore | [12] | 7Drotor | 7Drotor | 5 MW |

| [57] | 8Drotor | 8Drotor | 5 MW |

| [17] | 7Drotor | 3Drotor | 3 MW |

| [14] | 5Drotor | 5Drotor | 2 MW |

| [51] | 9–10Drotor | 5Drotor | 3 MW |

| [50] | 12Drotor | 4Drotor | 5 MW |

| [11] | 5–8Drotor | 5–8Drotor | 5 MW |