Drivers of CO2-Emissions in Fossil Fuel Abundant Settings: (Pooled) Mean Group and Nonparametric Panel Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Brief Literature Review

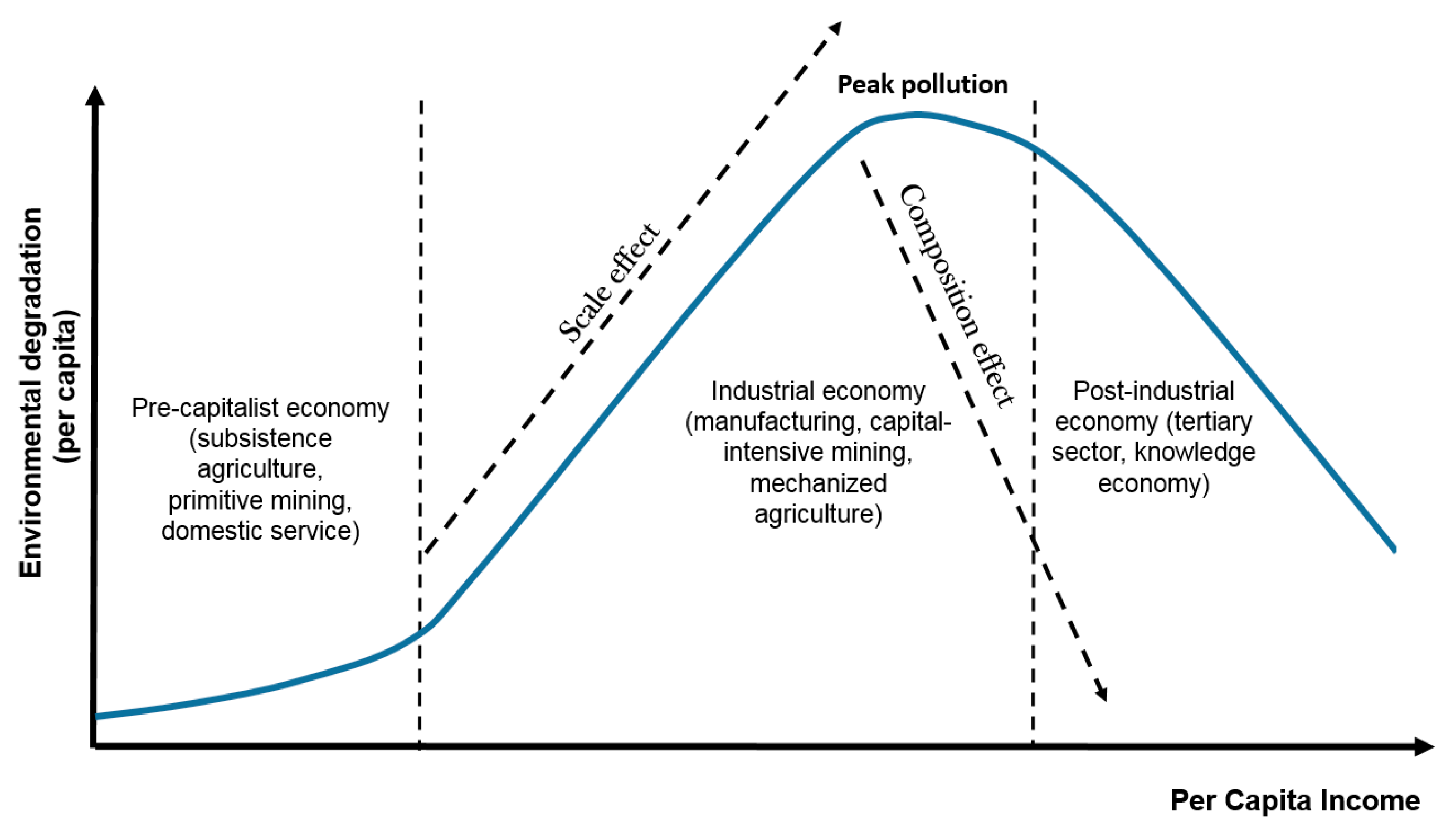

2.1. Income–Environment Relationship—The “Black Box”

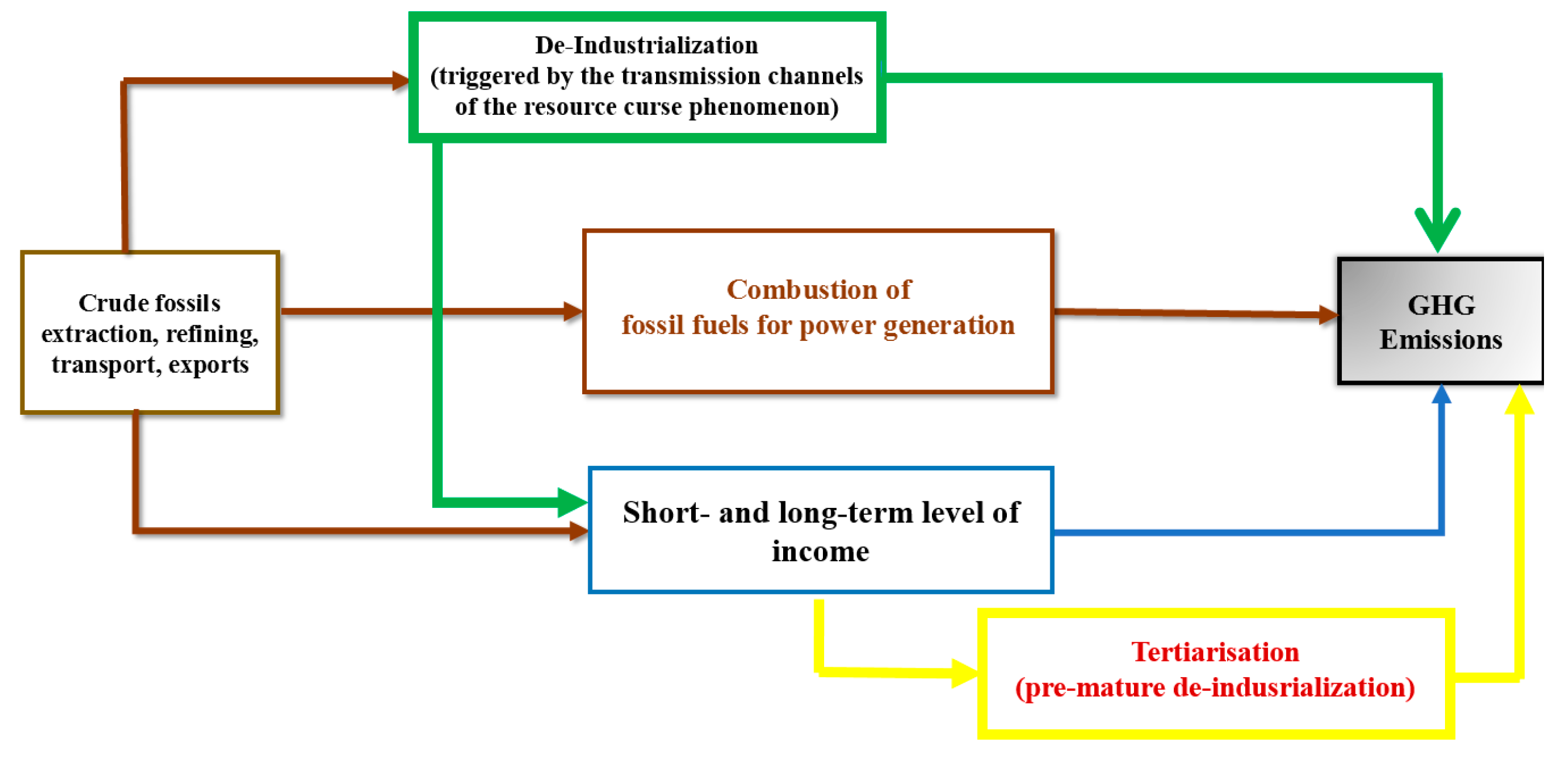

2.2. Inside the “Black Box”

- Q 1:

- Does the inverted U-shaped IER hold in the case of the oil-producing countries?

- Q 2:

- What is the net carbon-footprint of fossil-fuel abundance on the level of carbon dioxide emissions?

- Q 3:

- What are the essential drivers of carbon dioxide emissions in oil-producing countries?

3. Methodology

3.1. Multicollinearity and Confounding Variable Issues in Ecological Analyses

3.2. Parametric Specification

3.3. Pooled Mean Group Estimators and Dynamic Fixed Effects

3.4. Nonparametric Fixed Effect Panel Analysis

4. Data

5. Estimation Results

5.1. Parametric PMG Regressions

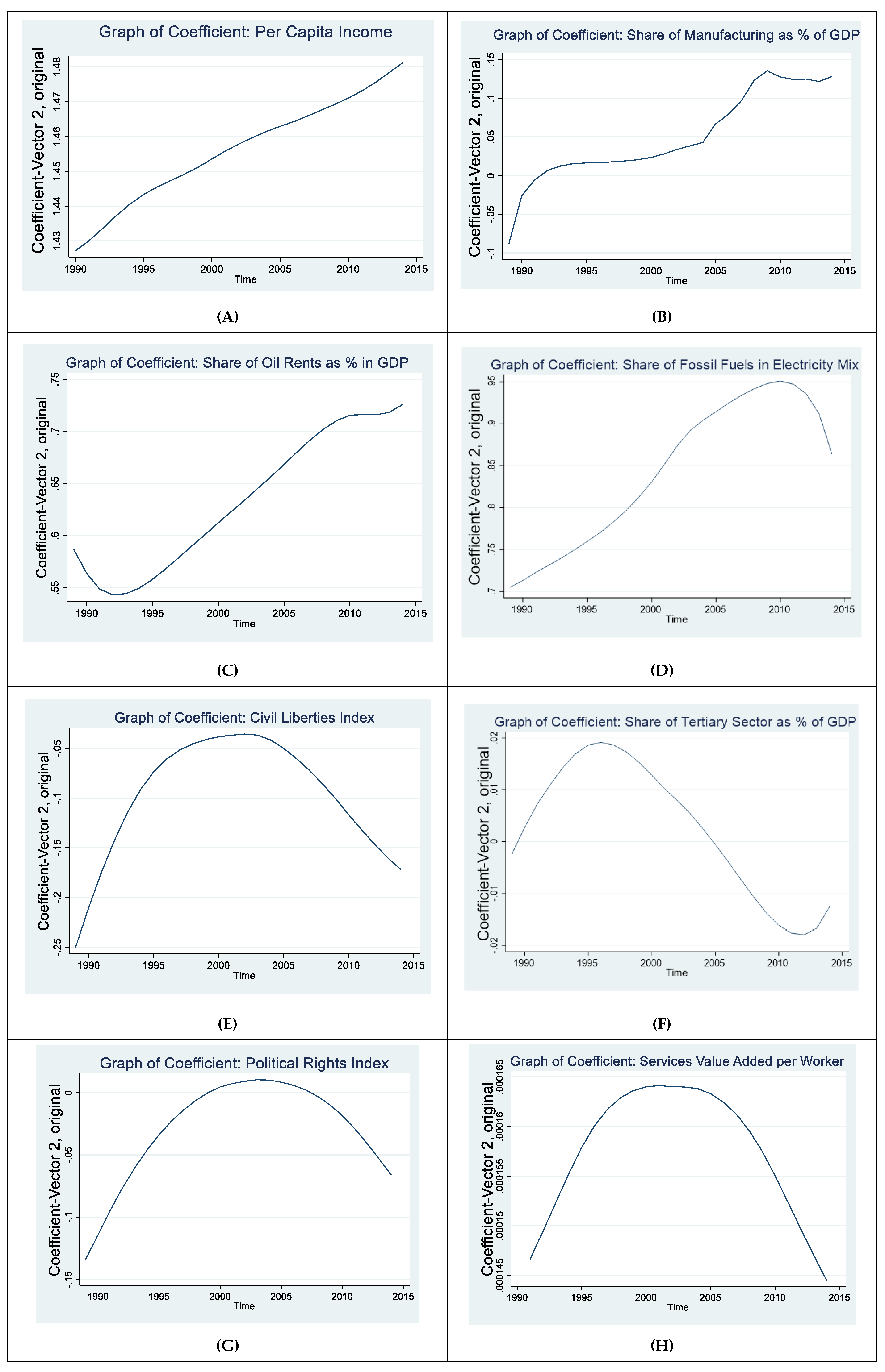

5.2. Nonparametric Analysis

6. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Variation Inflation Factor Statistics

| Variable | Variation Inflation Factor (VIF) | 1/VIF |

| lnMVA | 6.70 | 0.149278 |

| lnTVA | 6.63 | 0.150771 |

| ln_PCI | 2.00 | 0.500452 |

| ln_Power_fossils | 1.64 | 0.609550 |

| lnOil_Sh | 1.35 | 0.738673 |

| MEAN VIF | 3.66 |

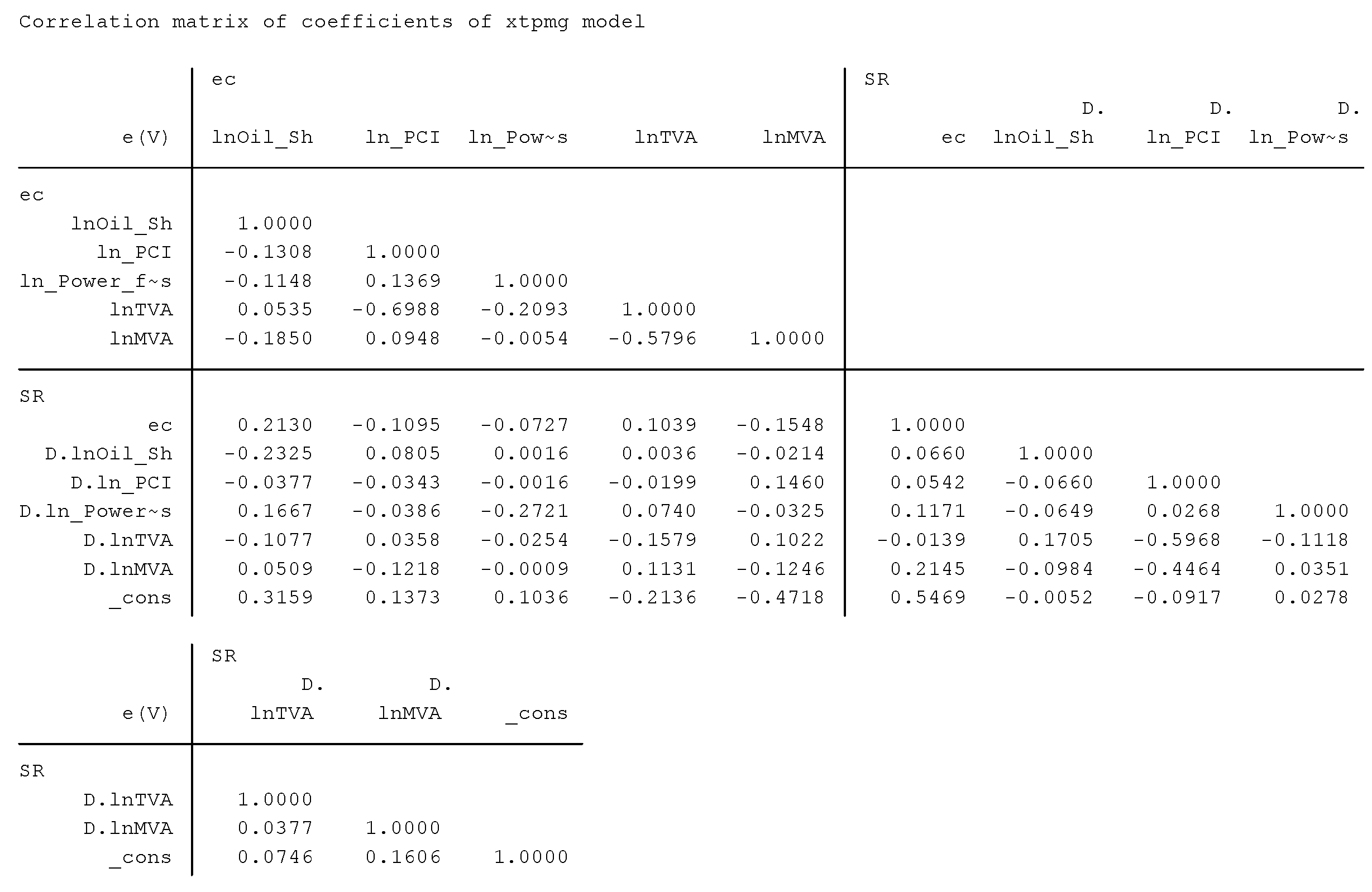

Appendix A.2. Correlation Matrix of XTPMG Model

Appendix A.3. List of Countries in the Estimations

| Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Australia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brazil, Brunei, Cameroon, Chad, Congo Rep., Ecuador, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Norway, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkmenistan, UAE, Venezuela, Vietnam |

Appendix A.4. Parsimonious PMG-Model to Assess the EKC Hypothesis

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

| Long Run | Short Run | |

| Error Correction Term | −0.333 *** | |

| (0.0465) | ||

| D.ln_PCI | 0.366 ** | |

| (0.170) | ||

| L2D.ln_PCI2 | 0.0272 | |

| (0.0736) | ||

| ln_PCI | 0.872 *** | |

| (0.137) | ||

| L2.ln_PCI2 | −0.108 | |

| (0.0668) | ||

| Constant | −1.722 *** | |

| (0.246) | ||

| Observations | 768 | 768 |

| Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. | ||

References

- Pearce, R. Paris 2015: Tracking Country Climate Pledges. Carbon Brief. 2020. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/paris-2015-tracking-country-climate-pledges (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- UCE. Each Country’s Share of CO2 Emissions. Union of Concerned Scientists. 2018. Available online: https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/each-countrys-share-co2-emissions (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- IEA. World Energy Balances. Overview. 2019. Available online: https://webstore.iea.org/download/direct/2710?fileName=World_Energy_Balances_2019_Overview.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Schauenberg, T. Tackling Climate Change from Kyoto to Paris. Deutsche Welle, Environment. 2020. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/kyoto-protocol-climate-treaty/a-52375473 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Jamieson, A. Climate Change Talks Bow to Pressure from Oil-Rich Saudi Arabia. EuroNews World. 2019. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2019/06/28/climate-change-talks-bow-to-pressure-from-oil-rich-saudi-arabia (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Ike, G.N.; Usman, O.; Sarkodie, A. Testing the role of oil production in the environmental Kuznets curve of oil producing countries: New insights from Method of Moments Quantile Regression. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 135208. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969719352003 (accessed on 15 May 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeli, A.; Abdoullahzadeh, N. Oil Exploitation and Environmental Kuznets Curve. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Gatto, A. The Puzzle of Greenhouse Gas Footprints of Oil Abundance. 2020. Unpublished preprint. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337324766 (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Ferrari, M. Environmental Policy Stringency, Technological Progress and Pollution Haven Hypothesis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Cain, M.; Pierrehumbert, R.; Allen, M. Demonstrating GWP: A means of reporting warming-equivalent emissions that captures the contrasting impacts of short- and long-lived climate pollutants. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 4, (online first). Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab6d7e (accessed on 23 May 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, M.; Lynch, J.; Allen, M.R.; Fuglesvedt, J.S.; Frame, D.J.; Macey, A.H. Improved calculation of warming-equivalent emissions for short-lived climate pollutants. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, P.R. The Population Bomb; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens III, W.W. The Limits of Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Potomac Associates Book: Washington, DC, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Malenbaum, W. Material Requirements in the United States and Abroad in the Year 2000: A Research Project Prepared for the National Commission of Materials Policy; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. Production, primary, secondary and tertiary. Econ. Rec. 1939, 15, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. The Conditions of Economic Progress; Macmillan and Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein-Rodan, P.N. Problems of Industrialisation of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. Econ. J. 1943, 53, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourastie, J. Le grand espoir du xxème siècle. In Progrès Technique, Progrès Économique, Progrès Social; Presse Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Nurske, R. Problems of Capital Formation in Underdeveloped Countries; Basil Backwell: Oxford, UK, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Holdren, J.P. Impact of Population. Science 1971, 171, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Environmental Impacts of A North American Free Trade Agreement. NBER Work. Pap. 1991. No. 3914. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w3914.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic Growth and the Environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayotou, T. Empirical Tests and Policy Analysis of Environmental Degradation at Different Stages of Economic Development; Working Paper WP238; Technology and Employment Programme, International Labor Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kaika, D.; Zervas, E. The environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) theory–Part A: Concept, causes and the CO2 emissions case. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1392–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.A. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labor. Manch. School 1954, 22, 401–449. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein, W.; Bender, D. Labor Market Failure, Capital Accumulation, Growth and Poverty Dynamics in Partially Formalised Economies: Why Developing Countries’ Growth Patterns are Different. SSRN Ecectrinic J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selden, T.M.; Song, D. Environmental Quality and Development: Is There a Kuznets Curve for Air Pollution Emissions? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1994, 27, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, A.C. Elements of Dynamic Optimization; Waveland Press Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, M. Endogenous Economic Growth, Climate Change and Societal Values: A Conceptual Model. Comput. Econ. 2017, 995–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous Technological Change. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Ferella, F. A socio-economic analysis of biomethane in the transport sector: The case of Italy. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Rosa, P. Recycling of end-of-life vehicles: Assessing trends and performances in Europe. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 152, 119887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komen, M.H.C.; Gerking, S.; Folmer, H. Income and environmental R&D: Empirical evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Dev. Econ. 1997, 2, 505–515. [Google Scholar]

- Liobikiene, G.; Butkus, M. The challenges and opportunities of climate change policy under different stages of economic development. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Treanton, K. Recent Trands in Energy-Related CO2 Emissions. Energy Policy 1998, 26, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M. Oily politics: A critical assessment of the oil and gas industry’s contribution to climate change. Energy Res. Soc. Sciance 2019, 50, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavenas, E.; Rosendahl, K.E.; Skjerpen, T. CO2-emissions from Norwegian oil and gas extraction. Stat. Nor. Discuss. Pap. 2015. Working Paper No. 806. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/forskning/discussion-papers/_attachment/225118 (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- IPIECA; American Petroleum Institute. Estimating Petroleum Industry Value Chain (Scope 3) Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Overv. Methodologies. 2016. Available online: https://www.api.org/~/media/Files/EHS/climate-change/Scope-3-emissions-reporting-guidance-2016.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Loewenstein, W.; Hasanli, Y. Production Linkages and Dynamic Fiscal Employment Effects of Extractive Industries: Input-Output and Nonlinear ARDL Analyses of Azerbaijani Economy. Mineral. Econ. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R. Oil Abundance and Economic Groth; Logos Verlag Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R. Distributional Bargaining and the Speed of the Structural Change in Oil-Exporting Labour Surplus Economies. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020, 31, 51–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Warner, A.M. Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth. NBER Work. Pap. No. 5398. 1995. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w5398 (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Corden, W.M.; Neary, P.J. Booming Sector and De-Industrialization in a Small Open Economy. Econ. J. 1982, 92, 825–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, D.; Tzivakis, J.; Green, A.; Charlton, D.; Lewis, K. Rural Development Programme measures on cultivated land in Europe to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions–regional ‘hotspots’ and priority measures. Carbon Manag. 2019, 7, 205–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Central. Greenhouse Sources in the US. 2018. Available online: https://www.climatecentral.org/gallery/graphics/greenhouse-gas-sources-in-the-us (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Mahdavi, H. The patterns and problems of economic development in rentier states. In Studies in the Economic History of the Middle East; Amy, C., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1970; pp. 407–437. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Loewenstein, W. A Note on Revenue Distribution Patterns and Rent Seeking Incentive. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2018, 8, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Duillieux, R.; Ragot, L.; Schubert, K. Carbon Tax and OPEC’s Rents under a Ceiling Constraint. Scand. J. Econ. 2011, 113, 798–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Fossil Fuel Subsidies. 2020. Available online: https://www.iea.org/topics/energy-subsidies (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Enerdata. Global Statstical Yearbook 2019. Available online: https://www.enerdata.net/about-us/company-news/energy-statistical-yearbook-updated.html (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Dasgupta, S.; Singh, A. Will Services be the New Engine of Indian Economic Growth? Dev. Chang. 2005, 36, 1035–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. Understanding economic policy reform. J. Econ. Lit. 1996, 34, 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- James, F.C.; McCulloch, C.E. Multivariate analysis in ecology and systematics: Panacea or Pandora’s box? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1990, 21, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.H. Confronting Multicollinearity in Ecological Multiple Regression. Ecology 2003, 84, 2809–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsley, D.A.; Kuh, E.; Welsch, R.E. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W.; Kutner, M.H. Applied Linear Regression Models; Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introduction to Econometrics: Europe, Middle East and Africa Edition; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, P. Statistical Methods for Geography; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Menard, S. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis: Sage University Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis, P.S.; Dunham, A.E.; Niewiarowski, P.H. Inferring multiple causality: The limitations of path analysis. Funct. Ecol. 1996, 10, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R. Addressing the growth and employment effects of the extractive industries: White and black box illustrations from Kazakhstan. Post-Communist Econ. 2020. (online first). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.; Sinani, E. When and where does foreign direct investment generate positive spillovers? A meta analysis. Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1075–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muethel, M.; Bond, M.H. National context and individual employees’ trust of the out-group: The role of societal trust. Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2013, 44, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Park, S.H.; Zhou, N. MNC strategy and social adaptation in emerging markets. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 842–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, T.; Puck, J.; Verbeke, A. Misconceptions about multicollinearity in international business research: Identification, consequences, and remedies. Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 283–298. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41267-019-00257-1 (accessed on 17 December 2019). [CrossRef]

- Carnes, B.A.; Slade, N.A. The use of regression for detecting competition with multicollinear data. Ecology 1988, 69, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alison, P.D. Multiple Regression: A Primer; Pine Forge Press: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R.A. Issues in multiple regression. Am. J. Sociol. 1968, 73, 592–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Gatto, A.; Saidik-Zada, E.R. A Composite Indicator for Waste-to-Energy and its Contribution to Energy Sustainability. Preprint. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330450048_A_composite_Indicator_for_Waste-to-Energy_and_its_Contribution_for_Energy_Sustainability (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Bertinelli, L.; Strobl, E. The Environmental Kuznets Curve Semiparametrically Revisited. Econ. Lett. 2005, 88, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azomahou, T.; Laisney, F.; Van, P.N. Economic development and CO2 emissions: A nonparametric panel approach. J. Public Econ. 2006, 90, 1347–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R. Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogenous Panels. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999, 94, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Smith, R. Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 1995, 68, 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, B.; Öztürk, I. Environmental Kuznets Curve: A Manual; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Zorzoso, I.; Bengochea-Morando, A. Pooled mean group estimation of an environmental Kuznets Curve for CO2. Econ. Lett. 2004, 82, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibril, H.; Chaudhuri, K.; Mohaddes, K. Asymmetric oil prices and trade imbalances: Does the source of the oil shock matter? Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111100, (online first). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, B.S. Testing the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis across the US: Avidence frpm panel mean group estimators. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackbourne, E.F., III; Frank, M.W. Estimation of nonstationary heterogeneous panels. Stata J. 2007, 7, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C. Panel data analysis—advantages and challenges. TEST 2007, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.A.; Srivastava, S.S. Correlation in Polynomial Regression. Am. Stat. 1979, 33, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shacham, M.; Brauner, N. Minimizing the Effects of Collinearity in Polynomial Regression. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 4405–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, J.; Gao, J. Nonparametric Time-Varying Coefficient Panel Data Models with fixed effects. Econom. J. 2011, 14, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Ullah, A. Profile likelihood estimation of partially linear panel data models with fixed effects. Econ. Lett. 2006, 92, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Hawthorne, K. Semiparametric estimation and testing of the trend temperature series. J. Econom. 2006, 9, 332–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Smyth, R.; Zhang, X. A Nonparametric Panel Data Model for Examining the Contribution of Tourism To Economic Growth. 2018. Preprint. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328758783 (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Lee, J.; Robinson, P.M. Panel nonparametric regression with fixed effects. J. Econom. 2015, 188, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Diallo, I.A. XTNPTIMEVAR: Stata Module To Estimate Non-Parametric Time-Varying Coefficients Panel Data Models With Fixed Effects, Statistical Software Components S457900; Boston College Department of Economics: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, D. Environmental Kuznets Curve in China: New Evidence from Dynamic Panel Analysis. Energy Policy 2016, 91, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvapulle, P.; Smyth, R.; Zhang, X.; Fenech, J.-P. Nonparametric panel data model for crude oil and stock market prices in net oil importing countries. Energy Econ. 2017, 67, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnqvist, L.; Pentti, V.; Vertia, Y.O. How Should Relative Changes be Measured? Am. Stat. 1985, 39, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes, C. Using “shares” vs. “log of shares” in fixed-effect estimations. J. Econ. Econom. 2011, 54, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Trax, M.; Brunow, S.; Suedekum, J. Cultural diversity and plant-level productivity. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2015, 53, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, K.-O.; Nicholson, M.; Oskarsson, S. Ethnic Enclaves and Elite Political Participation: Evidence from a Swedish Refugee Placement Program. CONPOL Working Paper 2018. Available online: https://conpol.org/working-papers/ (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Andersson, F.N.G.; Opper, S.; Khalid, U. Are capitalists green? Firm ownership and provincial CO2 emissions in China. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. General Diagnostic Tests for cross Section Dependence in Panels; CESifo Working Paper 1229; Centre for Economic Studies (CES) and Institute for Economic Research (ifo): Munich, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Calvacanti, T.; Mohaddes, K.; Raissi, M. Does Oil Abundance Harm Growth? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2011, 18, 1181–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotou, T. Demystifying the Environmental Kuznets Curve: Turning a black box into a policy tool. Environ. Dev. Econ. 1997, 2, 165–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, M.; Hammig, M. Institutions and the Environmental Kuznets Curve for deforestation: A cross-country analysis for Latin America, Africa and Asia. World Dev. 2001, 29, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, K. Governance, institutions and environment-income relationship: A cross-country study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 11, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B.H.; Hidalgo, J.; Li, Q. A Nonparametric Test for Poolability Using Panel Data. J. Econom. 1996, 75, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikayilov, J.I.; Galeotti, M.; Hasanov, F.J. The impact of economic growth on CO2 emissions in Azerbaijan. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1558–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunderson, R.; Stuart, D.; Petersen, B. The Political Economy of Geoengineering in Gas Plan B: Technological Rationality, Moral Hazard, and New Technology. New Political Econ. 2019, 24, 696–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, R.; Notle, A. Global aspiration and local (dis-)connections: A critical comparative perspective on tramway projects in Casablanca and Jerusalem. Political Geogr. 2020, 78, 102123, (online first). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsani, S.; Overland, I. Sovereign Wealth Funds and Public Financing for Climate Action. In Climate Action. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Ozuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description/Transformation | Source |

|---|---|---|

| LN_CO2_PC | Per capita carbon dioxide emissions. Carbon dioxide emissions are those stemming from the burning of fossil fuels and the manufacture of cement. They include carbon dioxide produced during consumption of solid, liquid, and gas fuels and gas flaring. | World Development Indicators 2020 |

| LN_PCI | Natural logarithm of GDP per capita. GDP per capita is gross domestic product divided by midyear population. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. It is calculated without making deductions for depreciation of fabricated assets or depletion and degradation of natural resources. Data are in constant 2010 U.S. dollars. | World Development Indicators 2020 |

| LN_PCI2 | Natural logarithm of the squared value of per capita GDP. | World Development Indicators 2019 |

| LN_Oil_Sh | Share of oil rents in total GDP. Oil rents are the difference between the value of crude oil production at world prices and total costs of production. | World Development Indicators 2019 |

| LN_MVA | Natural logarithm of the Manufacturing Value Added. Manufacturing refers to industries belonging to ISIC divisions 15–37. Value added is the net output of a sector after adding up all outputs and subtracting intermediate inputs. | World Development Indicators 2020. |

| Ln_Tertiarization | Natural logarithm of the share of services as a share of GDP. Services correspond to ISIC divisions 50–99 and they include value added in wholesale and retail trade (including hotels and restaurants), transport, and government, financial, professional, and personal services such as education, health care, and real estate services. | World Development Indicators 2020. |

| LN_POWER_FOSSILS | Natural logarithm of the share of electricity production from fossil fuels in total electricity production. Sources of electricity refer to the inputs used to generate electricity. Oil refers to crude oil and petroleum products. Gas refers to natural gas but excludes natural gas liquids. Coal refers to all coal and brown coal, both primary (including hard coal and lignite-brown coal) and derived fuels (including patent fuel, coke oven coke, gas coke, coke oven gas, and blast furnace gas). Peat is also included in this category. | World Development Indicators 2020. |

| Political Rights Index | The Political Rights index measures the degree of freedom in the electoral process, political pluralism and participation, and functioning of government. Numerically, Freedom House rates political rights on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the most free and 7 representing the least free. | The Freedom House 2020. |

| Civil Liberties Index | The Civil Liberties Index is a composite index that measures the degree of civil liberties. Numerically, Freedom House rates civil liberties on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the most free and 7 representing the least free. | The Freedom House 2020. |

| DEPENDENT VAR: CO2EMISSIONS PER CAPITA | Model 1 (PMG) | Model 2 (PMG) | Model 3 (MG) | Model 4 (PMG) | Model 5 (DFE) | Model 6 (DFE) | Model 7 (DFE) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Long-Term | Short-Term | Long-Term | Short-Term | Long-Term | Short-Term | Long-Term | Short-Term | Long-Term | Short-Term | Long-Term | Short-Term | Short-Term | Long-Term |

| Adjustment Term (ec) | −0.252 *** | −0.271 *** | −0.671 *** | −0.316 *** | −0.305 *** | −0.393 *** | -0.352 *** | |||||||

| (0.0395) | (0.0402) | (0.0678) | (0.0572) | (0.0258) | (0.0327) | (0.0331) | ||||||||

| D.lnOil_Sh | 0.0283 | 0.0144 | −0.0146 | 0.0270 | 0.003 | −0.00379 | −0.014 | |||||||

| (0.0273) | (0.0193) | (0.0289) | (0.0197) | (0.0132) | (0.0153) | (0.0146) | ||||||||

| lnOil_Sh | 0.126 *** | 0.0634 *** | 0.108 ** | 0.0287 *** | 0.0633 ** | 0.0537 ** | 0.102 *** | |||||||

| (0.0164) | (0.0184) | (0.0523) | (0.00995) | (0.0277) | (0.0233) | (0.023) | ||||||||

| L2.lnOil2 | 0.0437 *** | 0.00843 | ||||||||||||

| (0.00901) | (0.0240) | |||||||||||||

| L2D.lnOil2 | −0.0180 ** | −0.0115 | ||||||||||||

| (0.00820) | (0.00890) | |||||||||||||

| ln_PCI | 0.666 ** | 0.567 *** | 0.274 *** | |||||||||||

| (0.266) | (0.0252) | (0.095) | ||||||||||||

| D.ln_PCI | 0.340 * | 0.447 ** | 0.248 * | |||||||||||

| (0.182) | (0.212) | (0.1430) | ||||||||||||

| ln_Power_fossils | 0.265 *** | 0.090 * | 0.0692 * | 0.028 | ||||||||||

| (0.0450) | (0.0498) | (0.0408) | (0.0401) | |||||||||||

| D.ln_Power_fossils | −19.46 | 0.042 * | 0.0355 | 0.051 *** | ||||||||||

| (18.85) | (0.0221) | (0.0230) | (0.204) | |||||||||||

| ln_Tertiary | 0.312 *** | 0.125 * | −0.003 | |||||||||||

| (0.0567) | (0.074) | (0.004) | ||||||||||||

| D.ln_Tertiary | 0.193 * | 0.357 *** | 0.001 | |||||||||||

| (0.1935) | (0.1479) | (0.0019) | ||||||||||||

| lnMVA | 0.299 *** | 2.47 × 10−12 * | ||||||||||||

| (0.0849) | (1.49 × 10−12) | |||||||||||||

| D.lnMVA | −0.0466 | 1.28 × 10−12 | ||||||||||||

| (0.0863) | (1.36 × 10−12) | |||||||||||||

| Political Rights Index | −0.065 *** (0.0217) | |||||||||||||

| D. Political Rights Index | 0.016 (0.117) | |||||||||||||

| Constant | 0.191 ** | 0.178 ** | −3.941 ** | −1.665 *** | −2.199 *** | −3.844 *** | 0.588 *** | |||||||

| (0.0965) | (0.0899) | (1.611) | (0.310) | (0.4719) | (0.663) | (0.3149) | ||||||||

| Observations | 812 | 745 | 729 | 702 | - | - | - | |||||||

| Hausman | H0: PMG/H1: DFE | H0: PMG/H1: DFE | H0: PMG/H1: MG | H0: PMG/H1: MG | H0: MG/H1: DFE | - | - | |||||||

| 0.26 | 0.10 | 1.67 | 0.13 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Pesaran CD test statistics | 46.7 | 39.3 | 58.1 | 51.7 | 57.9 | 44.1 | 38.08 | |||||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Loewenstein, W. Drivers of CO2-Emissions in Fossil Fuel Abundant Settings: (Pooled) Mean Group and Nonparametric Panel Analyses. Energies 2020, 13, 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153956

Sadik-Zada ER, Loewenstein W. Drivers of CO2-Emissions in Fossil Fuel Abundant Settings: (Pooled) Mean Group and Nonparametric Panel Analyses. Energies. 2020; 13(15):3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153956

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadik-Zada, Elkhan Richard, and Wilhelm Loewenstein. 2020. "Drivers of CO2-Emissions in Fossil Fuel Abundant Settings: (Pooled) Mean Group and Nonparametric Panel Analyses" Energies 13, no. 15: 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153956

APA StyleSadik-Zada, E. R., & Loewenstein, W. (2020). Drivers of CO2-Emissions in Fossil Fuel Abundant Settings: (Pooled) Mean Group and Nonparametric Panel Analyses. Energies, 13(15), 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153956