Influence Factors on Carbon Monoxide Accumulation in Biomass Pellet Storage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pellet Manufacture and Its Characterization

2.1.1. Pelletizing

2.1.2. Proximate Analysis and Ultimate Analysis

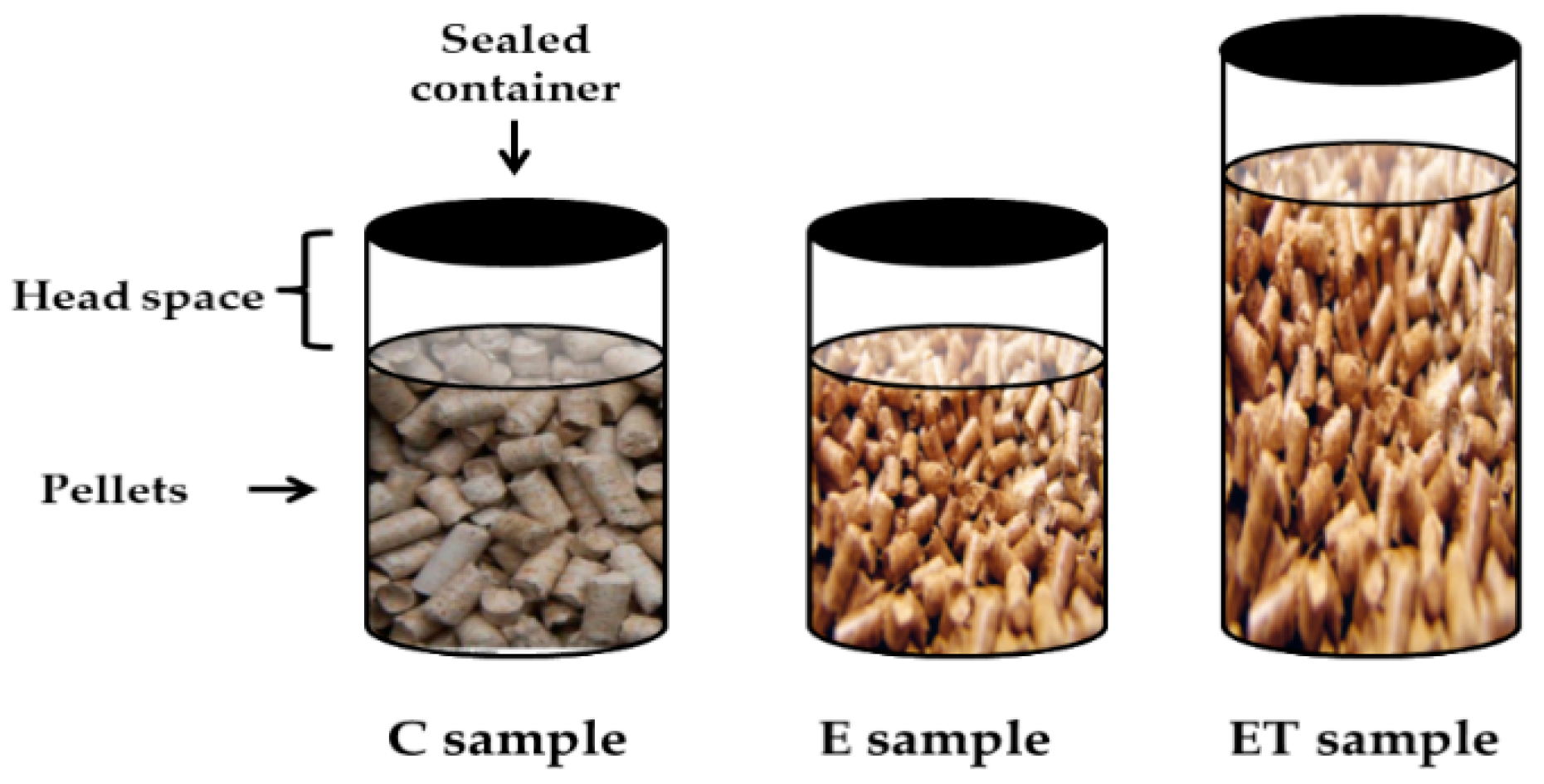

2.2. Sample Pellet Storage

- E: Eucalyptus pellets in 1-L containers;

- ET: In order to check the influence of sample quantity, the same eucalyptus pellets were stored in 2-L containers, keeping the same headspace.

- C: Cork powder pellets in 1-L containers. This different kind of pellet was selected to study the influence of raw materials on CO generation (comparing to the E samples).

2.3. Fat Content

2.4. CO Determination

2.5. Ventilation Experiments

- CO evolution without air renewal in an airtight container (Experiment 1). One single measurement was carried out for each sample, removing this sample after that.

- CO evolution with air renewal (Experiment 2). One single sample from each kind of material was selected when CO generation was stabilized (that is, 185 h after manufacture) in airtight conditions. Then several air renewals were done, measuring CO levels after sealing the same sample for 72 h.

2.6. Occupational Exposure Limits Standards.

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate and Ultimate Analysis

3.2. Fat Content

3.3. CO Concentration

3.3.1. CO Concentration without Air Renewal

3.3.2. CO Concentration with Air Renewal

3.4. Limit Value for Occupational Exposure

3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.6. General Considerations

4. Conclusions

- The different raw materials implied different CO emissions. In this case, the cork waste generated, under the same conditions, higher CO emissions than the eucalyptus pellets. This could be possibly due to its fatty acid distribution and its higher porosity, which makes the interaction of oxygen with fatty acids in wood easier, promoting its auto-oxidation. The concentration of elemental C (total) is also important because it is higher in cork waste samples.

- The amount of stored biomass to air quantity ratio was crucial to CO emissions. Higher amounts of the pellets, despite presenting the same headspace, produced higher CO emissions.

- According to the data, ventilation is highly advisable during pellet storage, especially at initial stages and up until auto-oxidation of wood is complete. During this stage, failure in ventilation could imply a dramatic increase in CO levels, even with lethal effects. However, the air flow to guarantee ventilation in confined spaces should be mild in order to avoid moisture in pellets, which could worsen their quality for energy use. Depending on the climate, different actions could be carried out to avoid this problem.

- The CO values obtained in this study exceed the legal exposure limits according to several regulations. Therefore, workers that carry out maintenance tasks in silos with similar raw materials should take protective measures.

- To sum up, continuous ventilation is highly advisable during pellet storage according to the findings in this study. Single initial ventilation was not enough and should be avoided. Ventilation ensured that CO was removed, but once the samples were isolated, its generation continued (decreasing its levels slightly for each consecutive air renewal). Therefore, auto-oxidation is a long process. This fact should be taken into account when designing ventilation equipment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gudka, B.; Jones, J.M.; Lea-Langton, A.R.; Williams, A.; Saddawi, A. A review of the mitigation of deposition and emission problems during biomass combustion through washing pre-treatment. J. Energy Inst. 2016, 89, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.S.; Yu, J. Chemical and light absorption properties of humic-like substances from biomass burning emissions under controlled combustion experiments. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 136, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijo-Kleczkowska, A.; Sroda, K.; Kosowska-Golachowska, M.; Musiał, T.; Wolski, K. Combustion of pelleted sewage sludge with reference to coal and biomass. Fuel 2016, 170, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E.J.S.; Lea-Langton, A.R.; Jones, J.M.; Williams, A.; Layden, P.; Johnson, R. The impact of fuel properties on the emissions from the combustion of biomass and other solid fuels in a fixed bed domestic stove. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 142, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, T.; Román, S.; Montero, I.; Nogales-Delgado, S.; Arranz, J.I.; Rojas, C.V.; González, J.F. Study of the emissions and kinetic parameters during combustion of grape pomace: Dilution as an effective way to reduce pollution. Fuel Process. Technol. 2012, 103, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartington, S.E.; Bakolis, I.; Devakumar, D.; Kurmi, O.P.; Gulliver, J.; Chaube, G.; Manandhar, D.S.; Saville, N.M.; Costello, A.; Osrin, D.; et al. Patterns of domestic exposure to carbon monoxide and particulate matter in households using biomass fuel in Janakpur, Nepal. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alakoski, E.; Jämsén, M.; Agar, D.; Tampio, E.; Wihersaari, M. From wood pellets to wood chips, risks of degradation and emisions from the storage of woody biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S.; Grass, H.; Lory, M.; Krämer, T.; Thali, M.; Bartsch, C. Lethal carbon monoxide poisoning in wood pellet storerooms—two cases and a review of the literature. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2012, 56, 755–763. [Google Scholar]

- Jämsén, M.; Agar, D.; Alakoski, E.; Tampio, E.; Vihersaari, M. Measurement methodology for greenhouse gas emissions from storage of forest chips—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihersaari, M. Evaluation of greenhouse gas emission risks from storage of wood residue. Biomass Bioenergy 2005, 28, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krigstin, S.; Wetzel, S. A review of mechanisms responsible for changes to stored woody biomass fuels. Fuel 2016, 175, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curci, M.J. Procurement, Process and Storage Techniques for Controlling Off-Gassing and Pellet Temperatures; Indeck Energy Biofuel Center: Buffalo Grove, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C.; Chiu, N.; Ho, C.; Peng, C. Carbon monoxide poisoning in children. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2008, 49, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, J.A. Health effects of exposure to ambient carbon monoxide. Chemosph. Global Change Sci. 1999, 1, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Shankar, T.J.; Bi, X.T.; Sokhansanj, S.; Lim, C.J.; Melin, S. Characterization and kinetics study of off-gas emission from stored wood pellets. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2008, 52, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuang, X.; Shankar, T.J.; Sokhansanj, S.; Lim, C.J.; Bi, X.T.; Melin, S. Effects of headspace volume ratio and oxygen level on off-gas emissions from stored wood pellets. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2009, 53, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuang, X.; Shankar, T.J.; Bi, X.T.; Lim, C.J.; Sokhansanj, S.; Melin, S. Rate and peak concentrations of off-gas emissions in stored wood pellets—Sensitivities to temperature, relative humidity and headspace volume. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2009, 53, 789–796. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.; Bi, X.T. Development of off-gas emission kinetics for stored wood pellets. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2013, 57, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Pa, A.; Bi, X.T. Modelling of off-gas emissions from wood pellets during marine transportation. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2010, 54, 833–841. [Google Scholar]

- Svedberg, U.; Petrini, C.; Johanson, G. Oxygen depletion and formation of toxic gases following sea transportation of logs and wood chips. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2009, 53, 779–787. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, F.; Sanz, R.; Abel, D.; Ezquerra, J.; Gil, A.; González, G.; Hernández, A.; Moreno, G.; Pérez, J.J.; Vázquez, F.M.; et al. Los Bosques en Extremadura. Evolución, Ecología y Conservación; Consejería de Industria, Energía y Medio Ambiente, Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Spain, 2007; Available online: http://extremambiente.juntaex.es/pdf/LibroBosquesWeb.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Montero, I.; Miranda, M.T.; Sepúlveda, F.J.; Arranz, J.I.; Trinidad, M.J.; Rojas, C.V. Analysis of pelletizing of wastes from cork industry. Dyna Energía Sosten. 2014, 3, 13. [Google Scholar]

- AEN/CTN 164—Biocombustibles sólidos. UNE-EN Standards; AENOR: Madrid (Spain). Available online: https://www.une.org/encuentra-tu-norma/comites-tecnicos-de-normalizacion/comite?c=CTN%20164 (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- UNE-EN ISO 18134-2:2017. Solid Biofuels: Determination of Moisture Content—Oven Dry Method—Part 2: Total Moisture—Simplified Method; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNE-EN ISO 18123:2016. Solid Biofuels: Determination of the Content of Volatile Matter; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNE-EN ISO 18122:2016. Solid Biofuels: Determination of Ash Content; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNE-EN ISO 16948:2015. Solid Biofuels: Determination of Total Content of Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNE-EN ISO 16994:2017. Solid Biofuels: Determination of Total Content of Sulfur and Chlorine; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNE-EN ISO 18125:2018. Solid Biofuels: Determination of Calorific Value; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNE-EN ISO 17831-1:2016. Determination of Mechanical Durability of Pellets and Briquettes; Part 1: Pellets; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNE-EN ISO 17828:2016. Solid Biofuels: Determination of Bulk Density; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Seguridad, Salud y Bienestar en el Trabajo (INSSBT), O.A., M.P. Límites de exposición profesional para agentes químicos en España 2018; INSSBT: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.insst.es/InshtWeb/Contenidos/Documentacion/LEP%20_VALORES%20LIMITE/Valores%20limite/Limites2018/Limites2018.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2019).

- Threshold Limit Values (TLV); ACGIH: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2015; Available online: http://dl.mozh.org/up/acgih-2015.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2019).

- MAK—Und BAT-Werte-Liste 2018: MaximaleArbeitsplatzkonzentrationen und BiologischeArbeitsstofftoleranzwerte. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9783527818402 (accessed on 29 March 2019).

- Arteaga-Pérez, L.E.; Grandón, H.; Flores, M.; Segura, C.; Kelley, S.S. Steam torrefaction of Eucalyptus globulus for producing black pellets: A pilot-scale experience. Biores. Technol. 2017, 238, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sette, C.R., Jr.; Hansted, A.L.S.; Novaes, E.; Fonseca e Lima, P.A.; Rodrigues, A.C.; de Souza Santos, D.R.; Yamaji, F.M. Energy enhancement of the eucalyptus bark by briquette production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 122, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Matias, J.C.O.; Catalão, J.P.S. Energy recovery from cork industrial waste: Production and characterisation of cork pellets. Fuel 2013, 113, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lau, A.K.; Sokhansanj, S.; Lim, C.J.; Bi, X.T.; Melin, S. Dry matter losses in combination with gaseous emissions during the storage of forest residues. Fuel 2012, 95, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtikangas, P. Storage effects on pelletised sawdust, logging residues and bark. Biomass Bioenergy 2000, 19, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Lim, C.J.; Bi, X.T.; Kuang, X.; Melin, S.; Yazdanpanah, F.; Sokhansanj, S. Analysis on storage off-gas emissions from woody, herbaceous and torrefied biomass. Energies 2015, 8, 1745–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, G.S.; Sartori, C.J.; Ferreira, J.; Miranda, I.; Quilhó, T.; Mori, F.A.; Pereira, H. Cellular structure and chemical composition of cork from Plathymenia reticulata occurring in the Brazilian Cerrado. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 90, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.M.A.; Sousa, G.D.A.; Freire, C.S.R.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Pascoal Neto, C. Eucalyptus globulus biomass residues from pulping industry as a source of high value tripterpenic compounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.R.; Guimaraes, M.; Oliveira, J.V.; Pereira, M.A. Production of added value bacterial lipids through valorisation of hydrocarbon-contaminated cork waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | UNE-EN ISO Standard |

|---|---|

| Moisture (%) (wb) | 18134-2 [24] |

| Volatile matter (%) (db) | 18123 [25] |

| Fixed carbon (%) (db) | -- |

| Ash (%) (db) | 18122 [26] |

| C (%) (db) | 16948 [27] |

| H (%) (db) | 16948 [27] |

| N (%) (db) | 16948 [27] |

| S (%) (db) | 16994 [28] |

| HHV * (kcal·kg−1) (db) | 18125 [29] |

| Durability (%) | 17831-1 [30] |

| Bulk density (kg·m−3) | 17828 [31] |

| E | ET | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Eucalyptus Waste | Eucalyptus Waste | Cork Waste |

| Approximate weight (g) | 300 | 750 | 350 |

| Head space volume (mL) | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Container volume (mL) | 1000 | 2000 | 1000 |

| Sample | Sampling Time | |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 (CO evolution without air renewal) | One single measurement after x hours from manufacture. After that, the sample is removed. | 2, 18, 29, 45, 135, 185, 233, 305, 353, 400, 800 and 848 h after pellet manufacture |

| Experiment 2 (CO evolution with air renewal) | One measurement on the same sample for each air renewal (9 in all), renewing air after each CO measurement and sealing the sample again. | 72 h after each renewal, doing 9 air renewals. |

| Time Exposure | CO Limit | |

|---|---|---|

| INSSBT (Spain) [32] | 8h (continuously) | 20 ppm |

| 15 min | 100 ppm | |

| ACGIH (USA) [33] | 8h (continuously) | 25 ppm |

| DFG (Germany) [34] | 8h (continuously) | 30 ppm |

| Parameter | Eucalyptus Waste | Cork Waste |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) (wb) | 11.88 | 5.53 |

| Volatile matter (%) (db) | 78.26 | 76.41 |

| Fixed carbon (%) (db) | 20.51 | 19.77 |

| Ash (%) (db) | 1.23 | 3.82 |

| C (%) (db) | 44.40 | 51.00 |

| H (%) (db) | 6.40 | 6.26 |

| N (%) (db) | 0.261 | 0.442 |

| S (%) (db) | 0.044 | 0.043 |

| HHV (kcal·kg−1) (db) | 4637.13 | 5185.52 |

| Durability (%) | 93.06 | 98.44 |

| Bulk density (kg·m−3) | 538.00 | 656.83 |

| Raw Material | Appearance | Fat (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Eucalyptus | Pellet | 0.09 |

| Powder | 0.12 | |

| Cork residue | Pellet | 0.27 |

| Powder | 0.41 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arranz, J.I.; Miranda, M.T.; Montero, I.; Nogales, S.; Sepúlveda, F.J. Influence Factors on Carbon Monoxide Accumulation in Biomass Pellet Storage. Energies 2019, 12, 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12122323

Arranz JI, Miranda MT, Montero I, Nogales S, Sepúlveda FJ. Influence Factors on Carbon Monoxide Accumulation in Biomass Pellet Storage. Energies. 2019; 12(12):2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12122323

Chicago/Turabian StyleArranz, José Ignacio, María Teresa Miranda, Irene Montero, Sergio Nogales, and Francisco José Sepúlveda. 2019. "Influence Factors on Carbon Monoxide Accumulation in Biomass Pellet Storage" Energies 12, no. 12: 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12122323

APA StyleArranz, J. I., Miranda, M. T., Montero, I., Nogales, S., & Sepúlveda, F. J. (2019). Influence Factors on Carbon Monoxide Accumulation in Biomass Pellet Storage. Energies, 12(12), 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12122323