Abstract

Construction contract management is an important research field in engineering. However, in construction contract management courses, student learning interest is decreasing because of unreasonable course design and management. Consequently, the use of project-based teaching (PBT) has increased in recent years. Nevertheless, there has been little research conducted to provide evidence that highlights the role of PBT among the factors of learning interest. This study aimed to investigate the factors that promote learning interest in PBT courses. First, we identified research gaps with a literature review and developed a potential research model. Second, a PBT course was carried out where 71 Tsinghua University students who attended the course were surveyed via 5-point Likert-scale questionnaires. Third, data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and the ordinal logistic regression model. Finally, the results were interpreted and discussed. Our findings show that there is a significant improvement in students’ learning interest towards the related course after the PBT method was adopted and that pedagogical factors, specifically (1) curriculum scope and sequence, (2) collaboration and communication, and (3) workload are the most salient factors that can influence student learning interest. None of the dispositional factors were found to significantly affect student interest. These results underpin the theoretical validity of PBT and can be used to improve PBT in engineering education management.

1. Introduction

According to The Future of Construction: A Global Forecast for Construction to 2030 Report [1], the global construction market has been expanding constantly and is expected to see a 35% growth in the next decade compared with the previous decade, which may lead to a situation where the demand for construction experts will increase significantly. In this context, education management is one of the keys to cultivating a more skilled and knowledgeable labor force, and it helps to further develop this flourishing construction field [2]. Contract management is an essential course in construction education. Most professional organizations within the field consider this course as an accreditation prerequisite [3]. Moreover, as stated by Coleman [4], effective contract management leads to a higher quality of construction work; hence, this statement further emphasizes the importance of the course.

Unfortunately, contract management courses are often deemed difficult by most architectural and construction students [3]. Students who undertake degrees in disciplines other than law often struggle to understand sophisticated legal principles, terminology, and ideas [5], which in turn may decrease their interest towards the contract management/legal issue course. Accordingly, we can infer that the majority of construction management students have a relatively low interest towards the contract management course. For this reason, we ensure that there are “needs” to focus on as ways to overcome the issue. Dewey [6] proposed that a better way to teach is to arouse learner interest instead of forcing them to work hard. We believe that by focusing on increasing student interest, students will better absorb knowledge and skills; consequently, it will result in a better learning outcome. To achieve this aim, one way to increase student interest toward this course is to change the teaching method.

Project-based teaching (PBT) methods have gained in popularity recently. This method teaches students through practical problems by creating a link between theory and practice [7]. PBT, as one of the constructivist methods, is considered student-centered and places more responsibility on students for their own learning as they actively construct and reconstruct their own reality while the lecturer acts as a facilitator in the process [8]. The strategy of student-centered active learning in PBT can increase the relevance of the subjects, make students more responsible for their learning, and consequently enhance their motivation to learn [9]. Based on this concept, we began to question whether and how the application of PBT to the contract management course may increase student interest in the course.

Although several researchers have attempted to explore the positive relationship between PBT and student motivation [8,10,11,12,13], they did not specifically focus on student interest and how the PBT concept can enhance the students’ learning interests. Furthermore, some studies that reported the factors influencing learning interest/motivation generally drew different conclusions [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

We propose the following core research questions. (1) What are the effects of students’ dispositional and pedagogical factors on their learning interest towards the courses; (2) Which factors have a significant effect, and which do not; (3) How should we improve the design of PBT based on students’ dispositional and pedagogical factors?

Finally, based on the core questions, this study extends prior work in multiple ways. First, we will consider factors that can enhance students’ learning interest in the PBT method in a more comprehensive way, exploring both pedagogical and dispositional factors. Second, we also explore the application of PBT in construction contract management courses, which, to the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have examined. Finally, this research will have practical implications, not only for the construction contract topic but also for the broader educational management field, to help design a better course to produce skilled and knowledgeable graduates for industries. A total of 71 Tsinghua University students who attended the construction contract management course, which was delivered using the PBT method, were surveyed. Furthermore, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and ordinal logistic regression (OLR) analysis were used to achieve the research objectives.

2. Literature Review

PBT, which promotes the modification of traditional teaching methods using pedagogical strategies and technologies, is a student-centered approach that emphasizes student interest, knowledge, and needs [19,20,21]. In this regard, the application of PBT may have a close relationship with student learning interest in one course. We argue that Hidi and Baird’s [22] theory of learning interest will be particularly useful in identifying the underlying factors of student interest in the PBT method. These authors stated that the role of interest during the education process falls under two categories, that is, personal interest, which concerns differences between individuals, and situational interest, which does not consider individual differences. In this study, we narrowed the scope of situational interest into five pedagogical factors and individual factors into four demographic backgrounds that affected students’ dispositional factors. A construction contract management course was adopted as a case study in this research.

2.1. Construction Contract Management

Construction contracts are an essential course in construction engineering education management. Most professional organizations in the field consider construction law and contract courses as accreditation prerequisites [3]. Contract management and administration is critical as civil engineers and architects are required to develop a good understanding of the rights and responsibilities of the many parties (owners, designers, contractors, suppliers, sureties, etc.) involved in construction projects and to comprehend all the essential items within the construction contract, such as scheduling and time management [23].

However, contract management courses are often deemed difficult by most architectural and construction students [3]. Students who undertake degrees in disciplines other than law often struggle to understand sophisticated legal principles, terminology, and ideas [5], which in turn may decrease their interest towards the contract management/legal issue course. From these statements, we can infer that the majority of construction management students had a relatively low interest towards the contract management course. Finding ways to increase their interest towards this topic is, thus, crucial.

A teaching construction contract will require a method that encourages application, synthesis, evaluation, and student-centered learning as this topic, particularly, involves detailed complex legal frameworks that students need to learn and apply [3]. Based on the assessment of student achievement, Adeyeye [3] again argues that construction contracts are best taught and understood if they are strengthened by practical experience or applications, such as case studies, scenarios, and legal cases. Accordingly, the application of PBT to construction contract courses is the ultimate way to achieve the objective of this course.

2.2. Project-Based Teaching

Unlike the traditional teaching methods where the teacher offers lectures in the classroom, a PBT method teaches concepts through practical problems, creating a link between theory and practice [7]. These associations enable students to grasp relevant theoretical knowledge better when faced with practical problems. In PBT, students should not be passive recipients of knowledge; instead, they must learn to develop situational contexts to apply knowledge to the real world based on their industry. PBT, as a constructivist method, is considered student-centered, which places more responsibility on students for their own learning as they actively construct and reconstruct their own reality, while the lecturer acts as a facilitator in the process [8]. From these definitions, we can infer that one of the emphases of the PBT method is the learner-orientated/student-centered concept.

The student-centered concept is based on the idea of constructivism, which states that students learn more by doing and experiencing than by observing, and it can be further defined as a form of active learning in which students are engaged and involved in what they are studying [6,24]. This strategy (student-centered active learning) increases the relevance of the subjects, making students more responsible for their learning and, consequently, enhancing their motivation to learn [9]. Some studies have also shown that student-centered concepts can help students in engagement, knowledge retention, depth of understanding, and appreciation of the subject being taught [25,26,27]. Some of the activities of this concept include, but are not limited to, involving students in simulations and role-plays, allowing students to lead the discussions, case studies, etc. [9]. These types of activities are referred to as an In-Class Challenge (ICC) in this study.

Bakla [28] explained that project-based learning can promote students’ active learning; accordingly, it may also promote their learning effectiveness and motivation. Bolstering this statement, Lin’s [29] research, which combined a PBT model with mobile learning for mathematics, showed that this teaching approach enhanced students’ learning interests and motivation, as well as promoted students’ learning effectiveness. The implementation and appreciation of the PBT approach has emerged in the last decade; however, the relationship between PBT and student learning interest and the factors influencing this interest still remain open for discussion.

2.3. Factors Affecting Learning Interest

Dewey [6] and Mitchell [30] discussed the relationship between learning and interest, and further addressed its importance. They proposed two factors in the construct of interest: identification and absorption. Moreover, they argued that if one recognizes and identifies with learning activities, he or she will devote attention to the learning process. Thus, Dewey [6] proposed that a better way to teach is to arouse learner interest, instead of forcing them to work hard.

According to Hidi and Baird’s theory [22], from researchers’ perspectives, we can identify the role of interest during the education process with two categories: personal interest, which concerns differences between individuals, and situational interest, which does not consider individual differences. Linnenbrink-Garcia [31] states that situational interest emerges in response to features in the learning environment. We limit situational interest in this study by exploring the pedagogical factors that might affect individuals’ learning interests.

As PBT has a number of different characteristics compared to traditional teaching methods, some variables can be assessed with regard to how these differences may affect student learning interest. Noting that PBT adapts a student-centered approach, which emphasizes students’ interest, knowledge, and needs [20], it can be assumed that the PBT method may have a high degree of correlation with the improvement in student learning interest; however, research gaps do exist, and they are described in the following.

2.3.1. Pedagogical Factors

Pedagogy is a set of instructional techniques and strategies that enable learning to occur and provide opportunities for the acquisition of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and dispositions within a particular social and material context [32]. PBT promotes the modification of traditional teaching methods through pedagogical strategies and technologies [19,21]. In this study, these pedagogical strategies are regarded as situational factors in terms of their relation towards student learning interest. There are several categories in this study raised as pedagogical factors that may affect student learning interest during the implementation of the PBT method.

- Workload

There is a perception that PBT methods will involve a significantly higher workload for students, as the assignment will require almost double the time required by the traditional teaching method [8]. Subsequently, students were reluctant to spend the additional time required for project-based assignments. Hence, Lo and Hew [33] mentioned that teachers should retain the workload of their course (as in the traditional format), as it was found that some students were upset because the pre-class workload of PBT overwhelmed their time at home. In this case, the workload required for the course will be an aspect worth mentioning when we want to explore the student interest, as the extra workload in PBT (i.e., time-consuming pre-class activities) may decrease student interest accordingly.

- b.

- Role-play

Teaching construction contracts, as a set of strict rules and regulations, is not an accurate depiction of what happens in actual projects; in contrast, teaching this subject should allow students to independently evaluate actions or events when drawing conclusions within contractual/legal issues [3]. Thus, an approach different from the traditional format during the teaching process of construction contracts should be adopted. Adeyeye [3] also found that students’ deep learning improved when lesson plans that encourage involvement and participation were implemented, including using role-play as a tool to prompt students to become more actively involved in their learning. Using this role-play approach, students will experience PBT from different stakeholders’ perspectives. Associated with learning interest, Wahyuni [34] found that this model had a statistically significant effect on improving student learning interest and critical thinking skills.

- c.

- Collaboration and communication

Currently, there are strong scientific data that explain the benefits of student learning and teamwork. Previous research has shown that teamwork promotes both academic achievement and collaborative activities [35]. In their research, Gillies and Boyle [36] stated that the benefits of collaboration and communication through teamwork would be consistent, irrespective of the students’ age (pre-school to university) and their major. Gillies [15,16] also emphasized that students who work in a team are more motivated to excel than when they work individually, and when they interact with others, they also learn to inquire, share their ideas, accept the differences, problem-solve, and construct new understanding through collaboration and communication. Numerous studies in various industries have noted that this activity is one of the key determinants to achieve a higher satisfaction level and will eventually increase student learning interest towards the course.

- d.

- Instructor’s Feedback

Apart from the learning processes, PBT also differs from traditional teaching with regard to the instructor’s role. The instructor’s role in this method is to help students develop self-monitoring skills to understand problems and identify solutions. By presenting the class with open-ended problems with no specific solution goals, students were forced to develop their own strategies and goals [7]. The instructor will become a coach as students work toward these autonomous goals. Rotgans and Schmidt [13] found that instructors play an influential role in increasing students’ situational interest in an active-learning classroom.

- e.

- Curriculum scope and sequence

Scope and sequence are terms used to identify the amount of content an educator will teach to participants (Scope) and the order in which they teach the selected content (Sequence). In PBT methods, instructors have to expend more effort designing courses that should be well-structured, concise, interactive, and relevant. The primary purpose of designing a high-quality PBT curriculum is to provide students with engaging and effective learning experiences in accordance with their own interests [37]. A comprehensive and efficient course structure that combines course and learning objectives should be perceived by the instructor when preparing this course [38]. Chen’s research [10] explored student perceptions, learning outcomes, and gender differences in a flipped mathematics course and found that the more female students were satisfied with well-designed courses, the better the learning outcome. Apart from that, a well-designed curriculum scope and sequence may allow students to feel connected to motivate them to interact more actively during the class. Boss and Larmer [39] introduced a framework for Gold Standard Project-based Learning consisting of seven essential project design elements: challenging problems/questions, sustained inquiry, authenticity, student voice and choice, reflection, critique and revision, and public products. These elements aim to set the PBT stage for a deep dive into the valuable academic content.

Based on the five pedagogical factors mentioned above, each of the factor has its own relationship with student interest. A review of previous studies shows that the instrument that is most influential on student interest remains unexplored. On one hand, it has been claimed that teamwork is one of the keys to increasing student motivation [15,16]. On the other hand, Rotgans and Schmidt [13] have also claimed that the instructor’s role is very influential on student interest. In addition, prior research tends to focus only on one or two specific factors within pedagogical strategies, not on covering more comprehensive instruments, and exploring which instruments are most influential.

Another research gap is that the majority of previous research focuses on the relationship between certain pedagogical factors and student motivation, not interests. Although students’ interests and motivations are closely related, whether these factors have a significant influence on student interest in PBT remains to be explored in more detail.

2.3.2. Dispositional Factors

From a dispositional factor perspective, people’s behavior/actions are generally believed to be influenced because individuals have personality traits that predispose them to engage in that behavior, not because of the context of the situation [40]. Bozionelos [41] has explored the association between a demographic group membership and dispositional factors, finding that both have shared effects on behavior and life outcomes. Hence, different demographic backgrounds may create a different dispositional trait, which eventually leads to a different level of learning interest towards one course. In this research, in addition to pedagogical factors, we will also explore the relationship between learning interest in PBT and four different demographic backgrounds: gender, enrollment year, major, and students’ Grade Point Average (GPA).

According to our review of previous studies, there have been conflicting results regarding the influence of certain factors towards student learning interests. Hasni and Cheung [14,18] in their research found that gender did not have a significant influence on student learning interests. In contrast, Glory [17] stated that gender had a statistically significant influence on student interests. Additionally, a similar case was found in the enrollment year background. McComb [12] believed that differences across enrollment years significantly affected student motivation to learn. On the other side, Fallon [11] argued that the differences among the classifications due to the different enrollment years (junior, sophomore, etc.) do not affect student motivation. Furthermore, in her research Fallon [11] also mentioned that students’ GPA statistically affect their motivation to learn.

Similar to pedagogical factors, based on our literature review, previous research has not covered all the factors comprehensively, combining situational and individual factors to determine which of them has the most significant influence on student interests. Again, most of them focused on students’ motivation, not their interests. All these aspects, concatenated with the conflicting results from previous research, have enticed us to explore more deeply the main factors in PBT that may affect student learning interest using a case study of the construction contract management course.

Accurately identifying all salient factors will underpin the foundation of designing the PBT course [42]. By identifying the factors that have a significant influence on the learning interest of students in PBT methods, this research has a theoretical and practical implication for not only the construction contract topics, but also for the broader educational management field, to help us design a better course that triggers student interest, enables their motivation, and supports productive engagement [43]. At the end, more skilled and knowledgeable graduates for the industries can be produced.

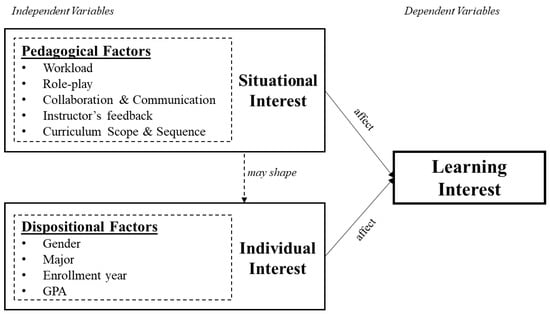

Both the pedagogical and dispositional factors in this research consist of five and four different items, respectively. In an attempt to fill the previously mentioned research gap, this study aims to explore how the PBT method in construction education can enhance student learning interest from a wider perspective. Thus, our research question is as follows: What are the main factors that can enhance student learning interest towards the construction education course delivered using PBT methods? (Exploring pedagogical and dispositional factors). The relationship between pedagogical factors and dispositional factors that serve as the independent variables in this research and student learning interest (dependent variables) is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model (Relationship Between Factors and Learning Interest).

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

We surveyed 71 students at Tsinghua University who attended a contract management course during the fall semester of 2021 about their individual characteristics (gender, major, etc.) and perceptions towards several questions leading to pedagogical factors of this course. In total, there were three different surveys distributed to the same respondents. Throughout the research project, our team maintained strict standards to protect respondents’ privacy. During data collection, the questionnaires and answers were accessible only to the members of the relevant research team. The data were limited to the basic demographic background, as well as students’ perceptions towards the course. Highly sensitive personal information was not collected in order to prevent personal security, ethics, and privacy issues. After data collection, all information was anonymized by removing all names and student IDs from data. All data were computed and averaged using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and then sent to the next stage processed by the SPSS® software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Finally, to answer the research question, both descriptive and interpretive (e.g., Wilcoxon test and OLR) statistical methods were used to analyze data. Prior to the Wilcoxon and regression analyses, we conducted several tests to ensure that all the statistical assumptions were met.

3.2. Participants

Participants were engineering undergraduate or graduate students who attended the Contract Management Class during Fall Semester 2021 at the School of Civil Engineering, Tsinghua University. The participants were treated as a sample of an engineering student population who attended a course delivered using a PBT method. A total of 71 students completed all three consecutive surveys; thus, the overall response rate for this survey was 100%. Among the 71 student participants, the gender breakdown was 51 (71.8%) males and 20 (28.2%) females. Furthermore, 31 (43.7%) participants were enrolled before 2019 (currently a sophomore/senior), while 40 (56.3%) were enrolled in and after 2019 (freshman/junior). Three engineering disciplines were included in the sample, with the majority of participants coming from construction management (49.3%). Among the students surveyed, we divided their prior academic achievement into three different groups according to their GPA (lower than 3.3, 3.3–3.7, and higher than 3.7). These three segmentations were based on the 4.0 GPA rating criteria where the score limit will be reflected in the score points by adding/subtracting 0.3–0.4 points (4.0, 3.7, 3.3, 3.0, 2.7, etc.). Furthermore, we selected the three aforementioned segments to obtain a more evenly distributed sample group. Descriptive statistical analyses of the data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of respondents’ background.

3.3. Independent and Dependent Variables

Mckenna [8] compared 27 different articles of PBT in civil engineering education, and they mentioned that the prior research tended to only focus on qualitative statements from student surveys; hence, it was necessary to explore the effectiveness of PBT in the research field of engineering education management using a more rigorous quantitative method. To adopt a quantitative method for the assessment of PBT, we can use questionnaire surveys, and Likert scale methods are extensively applied to measure students’ perceptions [8,44,45,46]. The dependent variable of our research model is student interest in learning towards the course. The question stem read, “The ICC brought my learning interests to this course.” The ICC (In-class Challenge) is the embodiment of a PBT approach within this contract management course. Participants responded using 5-point Likert-type scales, in which 1 corresponded with “Strongly Agree” and 5 to “Strongly Disagree.” Hence, answering 1 to this question indicates a very high interest of the students, while 5 indicates the lowest interest.

The independent variables in this study were predictors of student learning interest, consisting of pedagogical and dispositional factors. To capture students’ demographic background, we asked each participant about his or her gender, nationality, engineering discipline, year of enrollment, and prior GPA. There were five different questions in the form of 5-point Likert-type scales to measure students’ perceptions towards the pedagogical factors of this course. Similar to the dependent variable’s question, the answer to these independent variables was measured in which 1 corresponded to “Strongly Agree” and 5 to “Strongly Disagree.” The four dispositional factors of the students in this research were gender, enrollment year, major, and prior GPA. Furthermore, the five pedagogical factors within this research to explore the drivers of student interest are workload, role-play, collaboration and communication, instructor’s feedback, and curriculum scope and sequence.

3.4. In-Class Challenge

After the identification of the research gap, a course of construction contract management using the PBT method was carried out. We hypothesized that student interest in the class we designed would be affected by the application of the PBT approach. If the student interest increased, their engagement in the learning process would increase as well; hence, they will have a better contract management competency, noting that this topic is often deemed unattractive [3]. The main focus of this particular course was the ICC activities, which is an actualization of the PBT model. The ICC activities mix different modes of learning and include diversified activities to constantly stimulate students to work collaboratively with their group, facilitated by the lecturer. Through ICC, this class aimed to deliver a student-centered concept, teach concepts through practical problems, and create a link between theory and practice, following a concept different from traditional teaching methods [7].

Following previous research on PBT courses [9,47], the ICC that was implemented within this research consisted of a group project (each group including 5–6 people) and case studies, including role-plays, to allow students to experience the real situation of the construction contract management process. The student-centered concept in this research, which is recommended by Adeyeye [3], allowed students to learn more by doing and experiencing the negotiation, cost and schedule estimation, and contract administration process. As explained by Chinowsky and Rotgans [7,13] regarding the teacher’s role in PBT, we designed the course to focus on letting students lead discussions where the teacher only acted as the facilitator. With regard to the workload of the course, although we required students to perform a pre-class session and some group assignments, we tried to retain the workload as in the traditional format, as suggested by Lo [33].

3.5. Data Collection

We generated a total of 10 questions for the first and second questionnaires and 20 questions for the third one. Thirty-four 5-point Likert-scale items measuring independent and dependent variables were included in the surveys. Additionally, we also collected students’ characteristic data through individual profile questions (e.g., gender, nationality, current degree program, enrollment year, and prior GPA). Furthermore, strict standards for protecting respondents’ privacy were maintained throughout the research project. All data collected were accessible to the members of the relevant research team. We limited data and avoided collecting highly sensitive personal information to prevent personal security, ethics, and privacy issues.

Several measures were taken throughout the data collection process to ensure the high quality of the questionnaires. We involved experts in the field and some members of the target population in the question design, as it was an important step to ensure the validity of the scope of questions included in the tool (content validity) [48]. Our research team carefully designed questions to produce a clear and well-presented questionnaire. The survey was distributed three times, at the beginning, in the middle, and at the end of the class, to see the impact of implementing the PBT approach on student interest in this course. The professor and teaching assistant (TA) sent the link to these questionnaires through the course’s WeChat group, which was accessible to all students. The students responded to the surveys via the Tencent Questionnaire, an online survey application.

All the questionnaires were checked thoroughly, and our survey acquired a 100% response rate, where all 71 respondents answered all questions within the questionnaires. In addition, a validity test using Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity and a reliability test using Cronbach’s α test were conducted to ensure that the quality of the research tools met the criteria. The validity and reliability of the measurement results are discussed in Section 4.2.

3.6. Data Analysis

We generated a total of 10 questions for each of the first and second questionnaires and 20 questions for the third one.

Data pre-processing was conducted using Microsoft Excel, and the next stage was carried out using IBM SPSS® 25.0. Three analytical methods were adopted to achieve the research objectives.

- Descriptive statistics: To provide basic information about the variables in the dataset.

- Wilcoxon signed-rank test: To measure the enhancement of learning interest in student participants. As the survey results produce sets of ordinal data (5-point Likert scale), the outcomes are not expected to be normally distributed; hence, a non-parametric test can be used to measure the results [49]. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is a non-parametric test that measures two datasets from the same participants (investigating the changes in scores from one point in time to another) [50]; thus, this approach can efficiently measure the enhancement in student learning interest. As a non-parametric test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test requires only two assumptions to be met, that is, the data are ordinal, and the data samples are related [51]. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test finds the median to appropriately locate the center [52].

- OLR analysis: To address the core research question, finding the main drivers of learning interest in construction contract PBT, OLR analysis was adopted. The variables retrieved from the questionnaire were in the form of a 5-point Likert scale, and these ordinal data then represented a group of ordered dependent and independent variables. OLR is a suitable approach to achieve this objective [53].

Prior to Wilcoxon and OLR analyses, we conducted several tests to confirm that the required assumptions were met. For OLR, two important assumptions of the model were that the dependent variable is in order and “proportional odds” assumption would be met [53]. Validity and reliability tests were also conducted to ensure that the analysis conducted in this study was valid and reliable.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics of student learning interest in both the pre-test and post-test are presented in Table 2. The pre-test result shows the answers range from 1 to 4 for student learning interest towards the course, while the post-test result shows a different answer range from 1 to 3. The values are based on items with Likert scales from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates very high interest. The means of the data were 1.8 and 1.46 for the pre-test and post-test, respectively, indicating that respondents within this survey had a relatively high to very high interest towards this PBT method. The standard deviations of the pre-test and post-test data were 0.77 and 0.53, respectively, revealing that the individual data values are close to the means.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of students’ learning interest.

4.2. Validity and Reliability Measures

The dependent variable (learning interest) and pedagogical factors (consisting of five categories) were measured using questionnaires. Before proceeding with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and OLR analysis, we conducted a validity and reliability test to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the data. For the validity test, we concentrated on the KMO measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, while for the reliability test, the Cronbach’s α test was carried out.

Validity analysis was intended to prove that the data collected by the questionnaires were suitable for the study. The strong correlation between the measured items is reflected by the KMO value and Bartlett’s sphericity test value [54,55]. The criteria for the KMO value are as follows: The value should fall within the range from 0.6–0.7 to be suitable, 0.7–0.9 to be very suitable, and >0.9 to be completely suitable [54]. For Bartlett’s sphericity test, the value should be significant (<0.05) to determine whether the correlation coefficient between the items was significant [55]. The results in Table 3 show that KMO values are within the range from 0.7–0.9 (very suitable), and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant, which indicates that both pre-test and post-test data are valid.

Table 3.

Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire (KMO, Bartlett’s test of sphericity and Cronbach’s α).

Subsequently, to test the reliability of the variables obtained from the multiple Likert questionnaire, we performed a Cronbach’s α test. Cronbach’s α value for the post-test was 0.842 (>0.70), which demonstrates that the variables retrieved from questionnaires (pedagogical factors) are within the acceptable internal consistency range [56,57]. Cronbach’s α values for the pre-test were relatively lower (0.676). Although it is <0.70 (desirable result), values that fall within the from 0.6–0.7 range are also acceptable. Note that the number of items in this questionnaire was relatively small; hence, it may have a lower value [58].

4.3. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test

Regarding statistical inference, non-parametric tests were applied to test samples to evaluate student learning interest using a pre-test (1st questionnaire) and post-test (3rd questionnaire) quasi-experimental design. Significant improvements were only considered if the value was <0.05, in the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. As presented in Table 4, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the application of the PBT method in the construction course elicited a statistically significant change in the students’ learning interest (Z = −3.245, p = 0.001). Indeed, the median score rating was different, 2.0 and 1.0 for pre-test and post-test, respectively.

Table 4.

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test Result.

4.4. OLR

Table 5 presents the OLR models for predicting factors influencing students’ learning interest towards the problem-based teaching method in construction contract courses. Three regression models were used in this study. The first model predicted the influence of pedagogical factors towards student interest in learning, followed by the second model, which predicted the influence of dispositional factors, and the last model combined both pedagogical and dispositional factors within one regression model.

Table 5.

Results of ordinal logistic regression with independent variables.

Model 1 shows that there is a significant improvement in the model [χ2(5) = 46.82, p < 0.001], from which it can be interpreted that pedagogical factors significantly affect student learning interest towards the PBT method in construction contract courses. Workload (exp (B) = 2.19, p = < 0.1) and collaboration and communication (exp (B) = 4.26, p < 0.05) significantly influenced student interest in learning. Furthermore, curriculum scope and sequence (exp (B) = 5.44, p ≤ 0.05), which had the highest odds ratio, showed that while holding other factors fixed, for each additional perception level of course structure, the odds ratio of learning interest can increase by 5.44 times.

In Model 2, we explored four other independent variables of the dispositional factors. The results show that there is no significant improvement in the model [χ2(4) = 5.95, p ≥ 0.05], which indicates that dispositional factors cannot significantly affect student learning interest towards the PBT method in construction contracts.

Model 3, combining both factors, showed a significant improvement [χ2(9) = 49.30, p ≤ 0.001]. Among the nine independent variables included in the model, three variables have statistically significant results. This model strengthens the results of the analysis in Models 1 and 2 based on the regression model in our study, and the factors with the greatest influence in PBT are the pedagogical factor, while the dispositional factors have no significant relationship with student learning interest towards the course. The three pedagogical factors in regression Model 3 that significantly affected student learning interest were curriculum scope and sequence (exp (B) = 5.72, p ≤ 0.05), collaboration and communication (exp (B) = 3.87, p ≤ 0.1), and workload (exp (B) = 2.76, p ≤ 0.05).

5. Discussion

With the increasing popularity of PBT methods in the engineering education management field, we believe that our study will provide some theoretical and practical contributions to improve the current course design of PBT to be aligned with student learning interests. We believe that our research is applicable not only to construction students but also to a wider spectrum of engineering fields, as the construction contract management course within this research was conducted within the school of civil engineering, which was attended by students from different majors (construction management, civil engineering, and hydraulic engineering) and different enrollment years (freshmen, junior, sophomore, and senior). Civil engineering, which is sometimes considered to be one of the most essential majors in engineering education, requires graduates to demonstrate the ability to participate in and lead multidisciplinary teams [59]. Moreover, the course within this research requires pulling together knowledge from both technical (engineering and science) and non-technical (management) aspects. The broad scope of knowledge being delivered through this course, coupled with the all-round expertise of civil engineers, makes this research more accepted by different majors within engineering education fields.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

With regard to the contribution towards the field of construction education management, this research explores the PBT methods from a relatively new perspective, by exploring from the point of view of student interests. To the best of our knowledge, little research has been carried out that highlights the role of PBT methods among the factors of student learning interest. Most prior research has focused more on the positive relationship between PBT and student motivation, not specifically on learning interest [8,10,11,12,13]. The lack of exploration of the factors of learning interest towards the course delivered using the PBT method can be answered through this research.

We used two types of analyses (Wilcoxon signed-rank test and OLR) to illustrate the role of PBT among the factors of student learning interest towards the construction engineering education course. First, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a non-parametric test to measure the two datasets (pre- and post-test) from the same respondents, showed a significant result with a Z value of −3.245 (p = 0.001). This result indicates that there was a significant improvement in student learning interest (median changed from 2 to 1) towards the related course after the PBT method was adopted. The positive relationship between student learning interests and the adoption of PBT is consistent with the findings of prior studies. Gelisli [20] thought that PBT, utilizing a student-centered approach, emphasizes the interest, knowledge, and needs of students. Bakla and Lin et al. [28,29] found that PBT enhanced student learning interest and motivation and promoted learning effectiveness.

Referring to a similar cultural context, previous research exploring the application of PBT in some Chinese Universities has also been conducted. Pang [60] compared studies from different Chinese universities and concluded that the PBT model significantly stimulates student learning motivation. This situation further emphasizes our argument that the PBT model effectively increases student learning interest towards the course.

Our research question focused on the main factors that can enhance student learning interest towards the construction education course delivered using a PBT method. Thus, to find the most salient factors that affect student learning interest, we continued our analysis by performing separated OLR for three different models. The first and second models comprised only pedagogical and dispositional factors, respectively. The third model combined pedagogical and dispositional factors within a single regression model. All three models showed a consistent result, suggesting that only the pedagogical factors have significant effects on learning interest and act as positive predictors, while none of the dispositional factors significantly affected student learning interest.

The second model did not show a significant result [χ2(4) = 5.95, p > 0.05], thus, leading to a less informative outcome. However, both the first and third models showed a significant improvement in the fit of the final model over the null model with a likelihood chi-square ratio of [χ2(5) = 46.82, p < 0.001] and [χ2(9) = 49.30, p = < 0.001] for models 1 and 3, respectively. Furthermore, both models 1 and 3 consistently concluded the same three positive predictors of pedagogical factors that significantly enhanced student learning interest, including curriculum scope and sequence, collaboration and communication, and workload. The other contributing pedagogical factors (role-play and instructor feedback) also served as positive predictors, but they did not significantly influence the model.

Although there have been many articles emphasizing the importance of designing well-structured/well-designed courses [10,38], and a high-quality PBT curriculum should provide students with activities that align with their interest [37], this study tries to show that a well-structured/well-designed PBT course will significantly increase student learning interest. Therefore, our research underpins the prior articles empirically in that well-designed PBT curriculum scope and sequence should be pursued by the teacher to increase student learning interest within construction engineering education.

Gillies [15,16] shared that students who work in a team are more motivated to excel than when working alone, because when they worked interactively with others, they also learned to inquire, share their ideas, accept differences, problem-solve, and construct new understanding through collaboration and communication. Accordingly, collaboration and communication attained through teamwork generally served as one of the keys to achieving higher satisfaction levels and increasing student interest in the course. The significant value of collaboration and communication in our first and third models supported the theory that teamwork activities within a PBT course were key to increasing student learning interest.

The last significant positive predictor was the proper workload within the PBT course. This significant value of proper workload influence on student learning interest is consistent with Lo and Hew’s [33] finding that the extra workload in PBT (i.e., time-consuming pre-class activities) may decrease student interest; hence, teachers should pay attention to retaining the workload of their course so as not to overwhelm the students’ time at home with the additional pre-class workload.

Surprisingly, two the pedagogical factors (role-play and instructor feedback) that were significant in the previous study were not significant in this one. Wahyuni [34] found that a role-playing model had a statistically significant effect on improving students’ learning interest and critical thinking skills. The study conducted by Wahyuni [34] focused on the implementation of role-playing in chemical bonding materials, and they noted that not all subjects could use the role-playing model, as we had to consider the characteristics of the matter or subject. Although Adeyeye [3] has suggested the use of role-play as a tool to encourage involvement and students’ deep learning in construction contracts, our analysis results show that the use of role-play in PBT courses does not always mean that it significantly increases student interest in the subject. The role-play activities did not work properly in the group, the concept of the role-play that was not favored by the students, and students not taking the role-play activities seriously (not really portrayed their role during the discussion) were some of the possibilities that may affect student interest during the process, thus, justifying the insignificant results of the role-play activities within this research.

Unlike our findings, Rotgans and Schmidt [13] in their research found that instructors played an influential role in increasing students’ situational interest in the active-learning classroom. They explained that there were two options to increase students’ interests from the teacher’s side: increasing the teacher’s social congruence or increasing the teacher’s subject-matter expertise. Regarding our insignificant result of the instructor’s feedback towards the students’ interest, there might be a case where, in our research, both the teacher’s personal dispositional quality and their subject-matter expertise were not apparent to the students, and consequently, students’ opinions of the instructor’s feedback did not significantly influence their interest towards the course.

In addition to these two insignificant pedagogical factors, all dispositional factors in this study were also found to be insignificant. This finding supports previous research, which stated that gender [14,18] and different enrollment years [11] did not have a significant influence on student learning interest. Thus, this result refutes previous conflicting findings, which suggest that student gender [17], enrollment year, [12] and GPA [11] statistically affected student interest in learning.

The possibility of pedagogical factors in PBT solely playing a key role in influencing each individual’s interest regardless of students’ individual backgrounds might serve as one of the reasons for our research finding, showing that none of the dispositional factors have a significant result. For instance, if one course is delivered in a very interactive and interesting way, all students, regardless of their gender, enrollment year, major, and past achievement, will most likely show high interest. PBT, in this research, was adopted to deliver a construction contract management course, which is deemed unattractive by most students [3]; thus, by actualizing the student-centered concept throughout the course, this particular class will be an interesting new experience for all students regardless of each individual’s disposition factor.

In his meta-analysis, Solpuk [61] mentioned that the inconsistent result between the findings of dispositional factor traits towards people’s motivation may also be due to different types of research and sample groups. Finally, another possible reason for this insignificant result is the relatively limited number of respondents in this study, which may not appropriately represent the characteristics of each demographic group; hence, this will increase the margin of error in this study. Nevertheless, our study provides strong evidence that pedagogical factors, specifically (1) curriculum scope and sequence, (2) collaboration and communication, and (3) workload, are the most salient factors that can significantly influence student learning interest in the course delivered using the PBT method.

5.2. Practical Contribution

The results of the present study suggest that pedagogical factors in PBT can significantly increase student learning interest towards the subject. This finding reinforces the message that pedagogical intervention strategies can work to increase student interest and produce more skilled and knowledgeable graduates. Both the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and OLR presented here provide an insight into how academics within the construction education management field can utilize the PBT method to deliver their courses and maximize the benefits in enhancing student interest. To further elaborate on the practical implications based on the aforementioned theoretical analysis, we propose the following four suggestions for construction educators’ practices:

- Apply the PBT method, which emphasizes student-centered active learning in construction education courses. In accordance with previous research, based on our findings, we believe that adapting to PBT is an effective way to deliver essential construction courses since it can significantly increase student interest towards the subject. Certainly, this adoption of PBT should be accompanied by a propitious course design (which will be elaborated more through the second to fourth suggestions) to achieve its learning objectives.

- The curriculum scope and sequence of the PBT course should be prepared carefully. A well-designed curriculum scope and sequence will increase the students’ interest as it allows them to appreciate the course, feel the connectedness, and trigger themselves to interact more actively during the class. Therefore, instructors have to spend more effort in designing courses to ensure that they are well-structured, concise, interactive, and relevant. More detailed guidance on how to produce a high-quality PBT curriculum has been explained by previous studies, such as [37] who proposed six design process recommendations proposed by Tierney [37], and Boss and Larmer [39] who introduced a framework for gold standard PBT, and many others. Flexibility should also be upheld by allowing each participant to express their values and perceptions to the class [47]. Every effort should be made to make the class livelier and to avoid conflicts and non-participation from relatively less active students [47].

- Include group work that initiates collaboration and communication among students as an element in the PBT course. Students who work in a team will interact with their peers in that they can share their ideas, receive new perspectives from their teammates, and solve problems together. Through these activities, student interest also increased, and they were more engaged during the session. However, instructors and facilitators also need to ensure that the atmosphere in the group can be properly maintained by continuously monitoring the activities of students in small groups. Otherwise, group work can be a detrimental factor that reduces student interest. Kuppuswamy and Mhakure [47] also noted that it would be better, if during the group work of the PBT course, each group’s composition is distributed evenly according to their academic achievements (for example, each group consists of best, average, and marginal students), to avoid significant imbalance between teams and create new conflicts.

- Ensure that the PBT course can be delivered with retention of the traditional format’s workload. PBT methods usually involve more activities than traditional teaching methods, such as pre- and post-class activities and group assignments. When designing the course, it must be ensured that the activities and assignments of the course will not overwhelm the students’ time at home to avoid frustrating the students due to the extra workload in the PBT class, as frustration may reduce their interest towards the subject.

6. Conclusions

This study provides additional insights into the factors that promote learning interest in PBT courses within the field of construction education management. Through the literature review, several research gaps were found, such as limited research demonstrating how PBT affected student interest considering both situational and individual factors, and conflicting results of prior studies on the factors’ significance towards learning interest. Subsequently, a potential research model and a PBT course were developed. All the data for this study were collected and analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and OLR model to check student interest enhancement and explore the most salient factors underlying the enhancement of interest, respectively. Through the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a significant result of student learning interest enhancement was obtained, indicating that delivering a course using the PBT method may result in a significant improvement in students’ learning interest towards the related course.

Our OLR model results show evidence that pedagogical factors, specifically (1) curriculum scope and sequence, (2) collaboration and communication, and (3) workload, are the most salient factors that can significantly influence student learning interest towards the course using the PBT method. Moreover, none of the dispositional factors significantly affected the students’ interest. Regarding practical implications, four suggestions of pedagogical intervention strategies were proposed to further facilitate the construction engineering educators so that they can increase student learning interest and then the course can be delivered more effectively.

Apart from its theoretical and practical contributions, this study has certain limitations that leave more space for further research, such as the relatively limited sample size and unbalanced proportions among the different demographic groups. Hence, further research is recommended to survey a larger sample size and more balanced proportions of the respondent groups to examine the factors affecting student learning interest in PBT. In addition, future work might explore more factors from both situational and individual interests beyond the nine factors covered in this study to gain a more comprehensive understanding of this area. Finally, future research can extend and substantiate the importance of this study by exploring the positive outcomes resulting from increased student interest in PBT courses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.J.G., J.W. and P.-C.L.; methodology, T.J.G., J.W. and P.-C.L.; software, T.J.G.; validation, T.J.G. and J.W.; formal analysis, T.J.G. and J.W.; investigation, T.J.G., J.W. and P.-C.L.; resources, P.-C.L.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.J.G. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; visualization, T.J.G. and J.W.; supervision, J.W. and P.-C.L.; project administration, P.-C.L.; funding acquisition, P.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51878382).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee) of Tsinghua University, whose project identification code is THU201914.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that our data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51878382) for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Robinson, G.; Leonard, J.; Whittington, T. Future of Construction. A Global Forecast for Construction to 2030; Oxford Economics: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Chen, K.; Lu, W. Bibliometric Analysis of Construction Education Research from 1982 to 2017. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2019, 145, 04019005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, K. Teaching Construction Contracts: Mutual Learning Experience. J. Leg. Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2009, 1, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.; Nooni, I.K.; Fianko, S.K.; Dadzie, L.; Neequaye, E.N.; Owusu-Agyemang, J.; Ansa-Asare, E.O. Assessing contract management as a strategic tool for achieving quality of work in Ghanaian construction industry. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2020, 25, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monseau, S.C. Multi-layered assignments for teaching the complexity of law to business students. Int. J. Case Method Res. Appl. 2005, 17, 531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Interest and Effort in Education; Houghton, Mifflin and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Chinowsky, P.S.; Brown, H.; Szajnman, A.; Realph, A. Developing Knowledge Landscapes through Project-Based Learning. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2006, 132, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenna, T.; Richardson, M.; Gibney, A. Benefits and limitations of adopting project-based learning (PBL) in Civil Engineering education—A review. In Proceedings of the IV International Conference on Civil Engineering Education (EUCEET), Barcelona, Spain, 5–8 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Leighton, J. Exploring the Effectiveness of a Flipped Classroom with Student Teaching. e-J. Bus. Educ. Scholarsh. Teach. 2020, 14, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-C.; Yang, S.J.; Hsiao, C.-C. Exploring student perceptions, learning outcome and gender differences in a flipped mathematics course. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 47, 1096–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, E. A Dissertation entitled Academic Motivation and Student Use of Academic Support Interventions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McComb, S.A.; Kirkpatrick, J.M. Impact of pedagogical approaches on cognitive complexity and motivation to learn: Comparing nursing and engineering undergraduate students. Nurs. Outlook 2015, 64, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotgans, J.I.; Schmidt, H.G. The role of teachers in facilitating situational interest in an active-learning classroom. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D. The key factors affecting students’ individual interest in school science lessons. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 40, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.M. Structuring cooperative group work in classrooms. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2003, 39, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.M. The behaviors, interactions, and perceptions of junior high school students during small-group learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glory, G.-E.; Ihenko, S. Influence of Gender on Interest and Academic Achievement of Students in Integrated Science in Obio Akpor Local Government Area of Rivers State. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2017, 13, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasni, A.; Potvin, P. Student’s interest in science and technology and its relationships with teaching methods, family context and self-efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 337–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, S.; Eaton, J. The Partially Flipped Classroom. Teach. Psychol. 2018, 45, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelisli, Y. The effect of student centered instructional approaches on student success. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2009, 1, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shih, W.-L.; Tsai, C.-Y. Students’ perception of a flipped classroom approach to facilitating online project-based learning in marketing research courses. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidi, S.; Baird, W. Strategies for Increasing Text-Based Interest and Students’ Recall of Expository Texts. Read. Res. Q. 1988, 23, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalp, G.G.; Öcal, M.E. Determining Construction Management Education Qualifications and the Effects of Construction Management Education Deficiencies on Turkish Construction. Creative Educ. 2016, 07, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brown, J.K. Student-Centered Instruction: Involving Students in Their Own Education. Music Educ. J. 2008, 94, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonwell, C.C.; Eison, J.A. Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. 1991 ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports; Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED): Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, C.; Jones, T.B. Promoting Active Learning. Strategies for the College Classroom; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Talbert, E.; Hofkens, T.; Wang, M.-T. Does student-centered instruction engage students differently? The moderation effect of student ethnicity. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 112, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakla, A. Learner-generated materials in a flipped pronunciation class: A sequential explanatory mixed-methods study. Comput. Educ. 2018, 125, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-J.; Hwang, G.-J.; Fu, Q.-K.; Chen, J.-F. International Forum of Educational Technology & Society A Flipped Contextual Game-Based Learning Approach to Enhancing EFL Students’ English Business Writing Performance and Reflective Behaviors. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2018, 21, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. Situational interest: Its multifaceted structure in the secondary school mathematics classroom. J. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 85, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenbrink-Garcia, L.; Durik, A.M.; Conley, A.M.; Barron, K.E.; Tauer, J.M.; Karabenick, S.A.; Harackiewicz, J.M. Measuring Situational Interest in Academic Domains. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, I.; Sylva, K.; Muttock, S.; Gilden, R.; Bell, D. No 356 Researching Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years. January 2002. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277292962_No_356_Researching_Effective_Pedagogy_in_the_Early_Years (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Lo, C.K.; Hew, K.F. A critical review of flipped classroom challenges in K-12 education: Possible solutions and recommendations for future research. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2017, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahyuni, S.; Rahmatan, H. The effect of role-playing model on students’ critical thinking skills and interest in learning chemical bonds concept. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1460, 012089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, E.H. Group work as an incentive for learning – students’ experiences of group work. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.M.; Boyle, M. Teachers’ reflections of cooperative learning (CL): A two-year follow-up. Teach. Educ. 2011, 22, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, G.; Urban, R.; Olabuenaga, G.; Paulger, C. Designing Project-Based Learning Curricula: Leveraging Curriculum Development for Deeper and More Equitable Learning; Lucas Education Research: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Muthuprasad, T.; Aiswarya, S.; Aditya, K.; Jha, G.K. Students’ perception and preference for online education in India during COVID -19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2021, 3, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, S.; Larmer, J. Project Based Teaching: How to Create Rigorous and Engaging Learning Experiences; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kacmar, K.; Carlson, D.S.; Bratton, V.K. Situational and dispositional factors as antecedents of ingratiatory behaviors in organizational settings. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozionelos, N. Disposition and demographic variables. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, W.; Carey, L.; Carey, J.O. The Systematic Design of Instruction, 7th ed.; Pearson Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Järvelä, S.; Renninger, K.A. Designing for Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 668–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beagon, U.; Niall, D. Using a Problem Based Project to Develop Graduate Attributes in First Year Engineering Students. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual SEFI Conference, Orleans, France, 29 June–2 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- López-Querol, S.; Sánchez-Cambronero, S.; Rivas, A.; Garmendia, M. Improving Civil Engineering Education: Transportation Geotechnics Taught through Project-Based Learning Methodologies. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2015, 141, 04014007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghia, T.L.H. Motivations for Studying Abroad and Immigration Intentions. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 9, 758–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppuswamy, R.; Mhakure, D. Project-based learning in an engineering-design course—Developing mechanical- engineering graduates for the world of work. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, K.; Clark, B.; Brown, V.; Sitzia, J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2003, 15, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagabaldo, A.R.; Añosa, J.; Gapusan, J.; Soriano, K.; Uy, F.A.; Bacero, R. Determining the Potential Effects of the Proposed Removal of South Provincial Buses along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) using Commuters’ Perception. J. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2017, 12, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, D.; Neuhäuser, M. Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank Test. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1658–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S. Business Research Methods, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J.W. Simple Linear Models With Polytomous Categorical Dependent Variables: Multinomial and Ordinal Logistic Regression. In Regression & Linear Modeling: Best Practices and Modern Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. A note on the multiplying factors for various χ2 approximations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1954, 16, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, N.; Kemp, R.; Snelgar, R. SPSS for Psychologists; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, A.; Jewell, T.K.; Wolfe, F.A. Perception Vs. Reality In Civil Engineering Education Today. In Proceedings of the 2003 Annual Conference, Nashville, Tennessee, 22 June 2003; pp. 8.922.1–8.922.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Su, M. The Application of PBL English Teaching in Engineering Universities. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2022); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 2663–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, N.S. Gender Differences in Academic Motivation: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2020, 7, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).