Complete bilateral cleft lip and palate (BCLP) patients show a characteristic anterior projection of the premaxilla which often persists even after lip repair [

1] This anatomical feature in BCLP children together with an increased overjet predisposes this region to trauma. Silva et al. [

1] found that 53% had suffered from oral trauma in their sample of 106 BCLP children, the majority sustained soft tissue lesions (91%) and dental trauma including avulsion, luxation, and intrusion of teeth were observed in the rest. Most of these events occurred at home and were observed before the age of 3 years; a period where toddlers’ attempts to walk and falls are frequent [

1].

Although dental trauma has been reported widely, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, any reports related to bone fractures of the vomero-premaxillary junction in BCLP patients have not been published in English literature. The aim of this report is to illustrate clinical findings and the technique of fracture fixation in a child suffering from a fractured vomero-premaxillary junction as well as subsequent columella lengthening.

Case History

On December 7, 2011, a 4-year-old girl born with a bilateral cleft lip, alveolus, hard and soft palate was referred to a cleft surgeon at the Wilgers Hospital, Pretoria, Republic of South Africa, with a fracture of the vomero-premaxillary junction.

Previously the girl had undergone primary lip repair at the age of 4 months, closure of the soft palate at the age of 11 months, as well as repair of the hard palate at the age of around 16 months elsewhere.

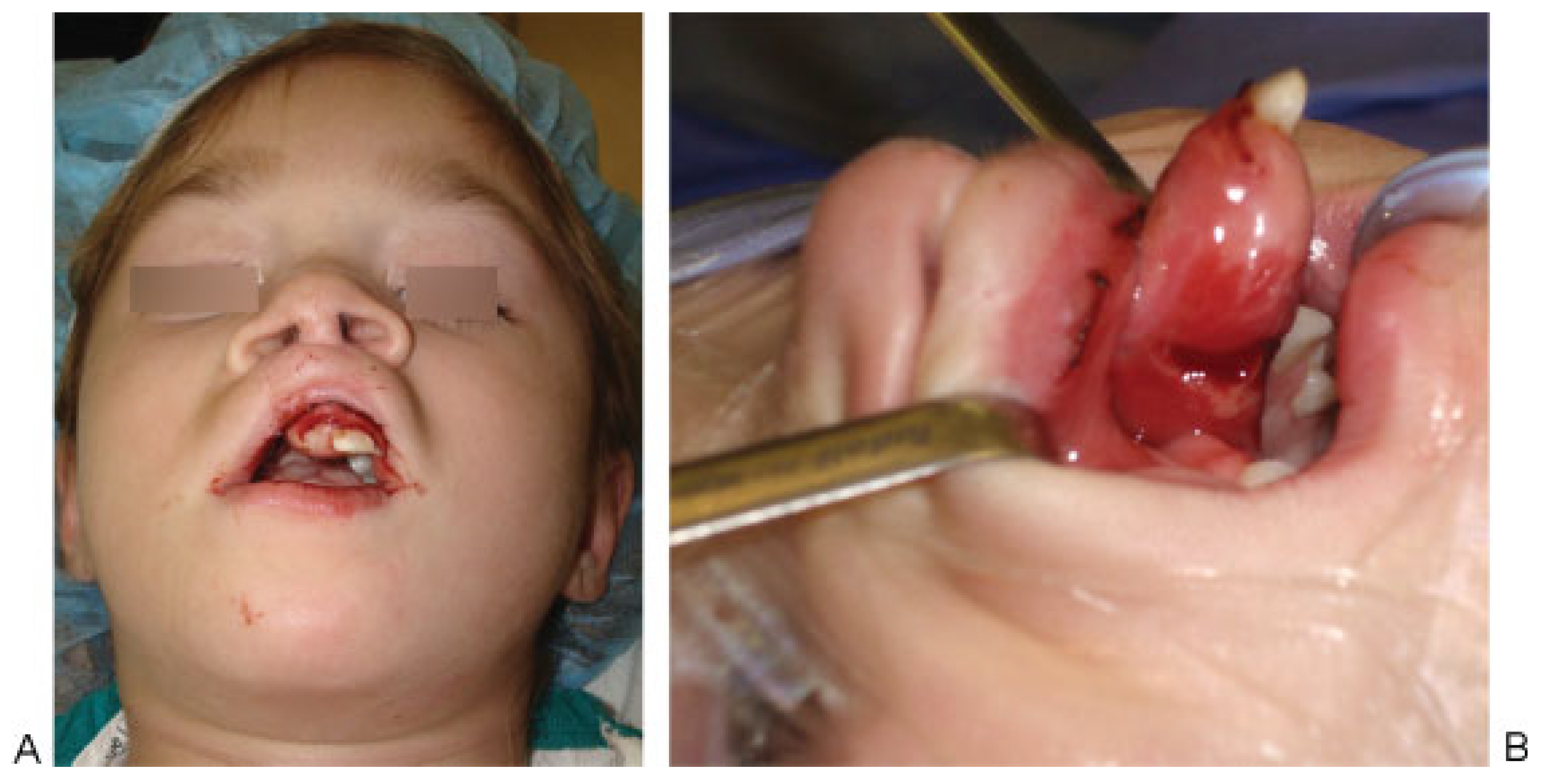

Trying to stand up in her cot, the girl slipped and fell with her face hitting a bar. Due to the extensive bleeding from the nose and the displaced premaxilla, the parents presented the girl to their previous plastic surgeon who immediately referred her to another specialist in cleft surgery in Pretoria. On examination, extraoral sensorimotor functions revealed normal findings. The excessive bleeding from both nostrils was controlled applying moist saline packages around the nose and premaxilla. Although the nose did neither show any increased mobility nor deviation, the premaxilla was dislodged to the left side (

Figure 1A). The eye motility was free in all directions. No bony irregularities were palpable at the orbital rim and the mandibular body. The premaxilla was totally mobile and was deviated to the left side. All teeth, including the deciduous incisors, were present, the latter showed no sub- or luxation. A mucosal laceration (

Figure 1B) with bone exposure was detected on the height of the vomero-premaxillary junction site.

The open laceration with its bony fracture confirmed findings of a fractured vomero-premaxillary area. Around the fracture site, the premaxilla was pedicled superiorly at the vomerine mucosa. On December 8, 2011, open reduction and fixation of the dislocated premaxilla was performed under general anesthesia. After disinfection and draping, the fracture site was accessed through the intraoral mucosal laceration (

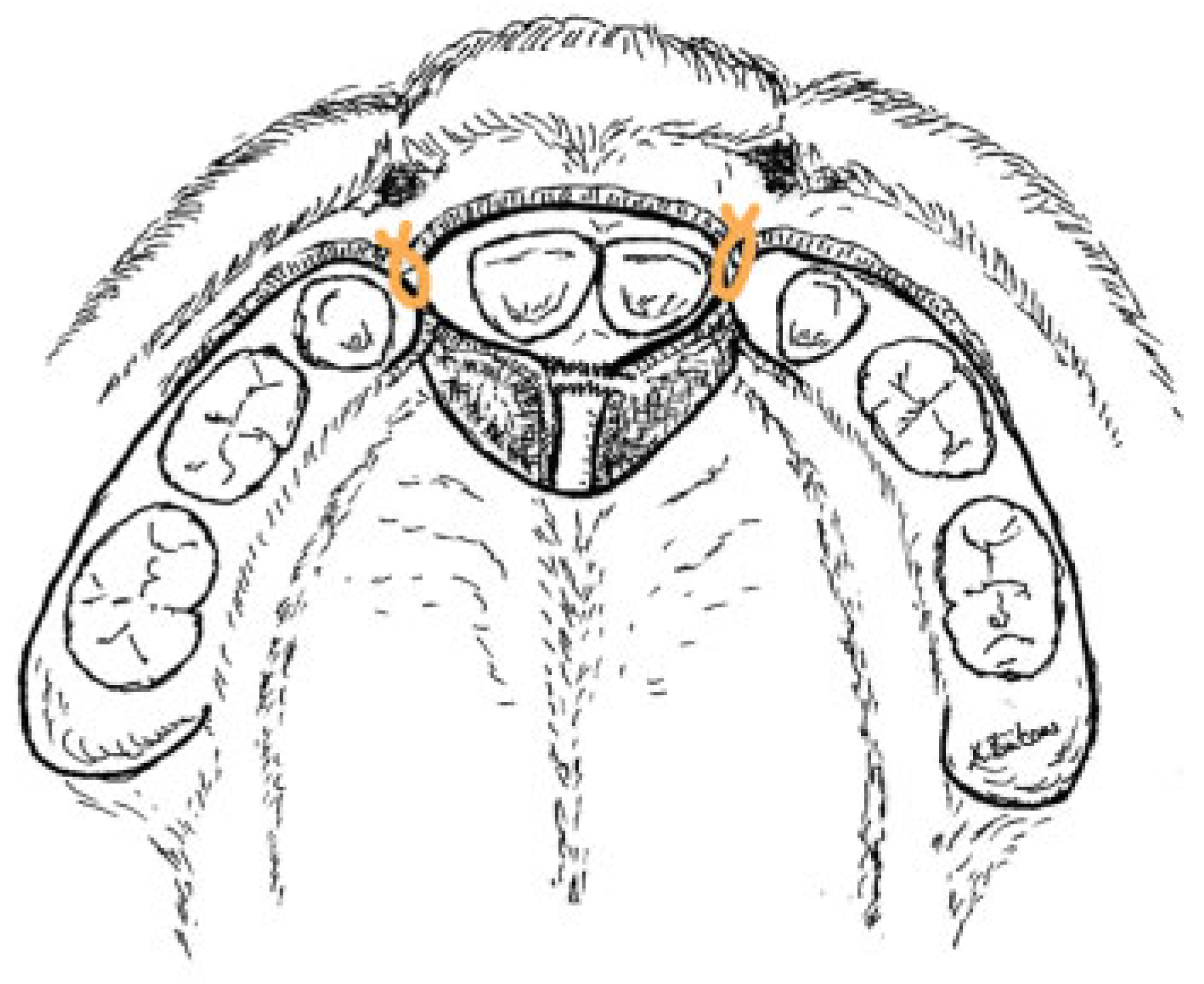

Figure 1B). Fractured bone pieces of the vomero-premaxillary junction were removed and sharp bone edges at the vomer and the premaxilla were grinded. Due to this sagittal shortening of the vomero-premaxillary structure, a setback of the premaxilla became feasible together with its alignment between both lateral alveolar arches. To fix the premaxilla in this position, additional surgical incisions became necessary on the lateral border of the premaxilla and lateral alveolar arches [

2] The repositioned premaxilla was fixed to the lateral alveolar arches with two mucoperiosteal sutures using PDS 3–0 (Johnson & Johnson, Pretoria, Republic of South Africa) on each side (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). During repositioning and bulging of the mucosa at the fracture site, the premaxilla became slightly ischemic; however, it recovered quickly after the mucosal closure with Vicryl 4–0 (Johnson & Johnson) in single stitch technique.

The recovery phase was uneventful. All family members were very happy about the new aesthetic aspects of the girl who for them looked for the first time ever quite “normal.” In the postoperative course, mucosal fusion occurred between the fixed premaxilla and the bilateral lateral alveolar arches (

Figure 4).

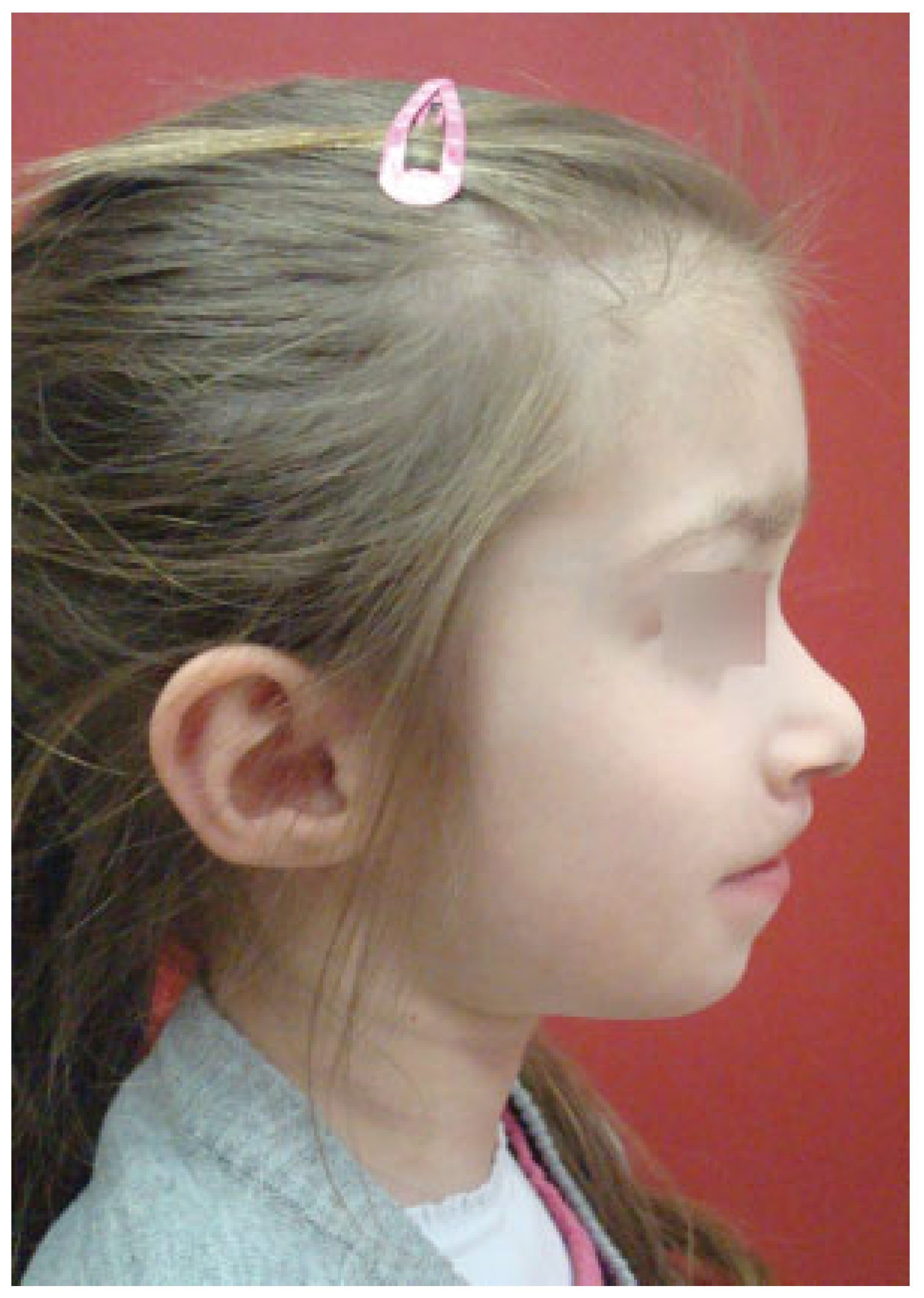

On February 19, 2013, columella lengthening was performed (

Figure 5) according to the modified technique of Cronin, described already elsewhere [

2,

3,

4]. Due to this surgery, the dome projection and narrowing of the nasal base improved very much contributing both to the aesthetics as well as to the psychological well-being of the patient and the family (

Figure 6).

Discussion

Managing the protrusive premaxillary segment in BCLP patients has always been a heatedly debated issue [

5,

6]. Some authors stated that untreated premaxillary segments may lead to serious problems such as lack of proper anterior occlusion, segment mobility compromising articulation, and oronasal fistulae jeopardizing the maintenance of oral hygiene [

7]. While soft tissue and dental trauma in children with protruded premaxillae have been reported in the literature [

1], fractures of the vomero-premaxillary junction seem to be rare.

The management of the vomero-premaxillary junction trauma in pediatric cleft patients entails specific challenges for health care providers. Besides anatomical characteristics of BCLP patients, knowledge of the subtle blood perfusion of the premaxilla is of utmost importance when performing incisions for open reduction and internal fixation or the repositioning of the premaxilla. Routine vestibular access, as in non-cleft patients, needs to be avoided, as the perfusion comes mainly from the vestibular labial and the nasal-septal mucosa. Lack of bone, the presence of permanent tooth buds, and skeletal growth constitute challenges regarding internal fixation [

8] Bone appositional growth pattern in children leads to migration of osteosynthesis material, plates, and wires [

9]. Therefore, resorbable materials are usually used in children for internal fixation after fractures. Such material, compared with their nonresorbable counterparts, needs to be larger in size to withstand physical forces resulting from growth and resorb slowly. However, the use of these materials would be problematic in our case due to the limited amount of premaxillary and adjacent alveolar bone.

Eventual nose bleeding from the sphenopalatine artery needs to be controlled as limited cardiovascular compensation mechanisms in children might lead to a quick systemic oxygen shortage. Besides the above-mentioned issues, BCLP children may be affected psychologically due to aesthetic shortcomings. They may also face difficulties in their language development related to articulation as well as in their food intake due to insufficient lip closure.

In the presented case, anatomical and physiological characteristics were taken into consideration during the preoperative management, surgical access, and the open reduction and fixation. First, the nasal bleeding, at the septum–vomer junction, was managed with nasal packages. Second, keeping the vestibular and nasal mucosa attached to the premaxilla led to continuous perfusion of the latter during the surgery. Third, the fixation of the premaxilla with mucoperiosteal resorbable suture material provided enough stability to guarantee mucosal fusion between premaxilla and lateral alveolar crests [

2]

Although rare, fractures of the vomero-premaxillary junction present several challenges to clinicians related to anatomical, physiological, and psychological issues. Immediate and minimal invasive treatment strategies are recommended when managing such cases.