Free flap reconstruction of the head and neck is routine following tissue loss from trauma, infection, malignancy or osteoradionecrosis. The functional outcomes of these flaps can be excellent in terms of replacement of skin, fat, bone and even neural function [

1]. Unfortunately, despite the wide spread availability of donor sites, mismatch frequently occurs be- tween cutaneous pigmentation from the donor site and the complex pigmentation of the head and neck. This leads to a significant compromise of the cosmetic outcome in what is frequently the most visible part of the body [

2]. Local flaps and skin grafts may provide an improved color match for the defect site, however, they are limited in terms of size, available tissue types and suffer problems of donor site morbidity [

3].

Various methods exist to improve the appearance of the cutaneous portion of free flaps. These include excision of the dermal component and grafting with pigmented skin (e.g., scrotal skin or scalp skin [

3]), serial excision of skin paddles, and medical tattooing. The first two of these options involve further surgical procedures and the potential for donor site morbidity. In addition, their suitability may be compromised by the size of the skin paddle or poor color match.

Medical tattooing is an alternative that avoids donor site morbidity and which is not affected by the size of the skin paddle. It is well reported in the cosmetic literature for permanent makeup such as lip pigment augmentation, eye-brow enhancement and the treatment of vitiligo [

4]. It also plays a role in reconstructive techniques including in breast reconstruction where it allows pigmentation of the areola [

5]. A high degree of patient satisfaction is described with the technique [

6]. The use of tattooing in head and neck reconstruction has been described for reconstruction of the vermilion of the lips [

7,

8]. However, the potential for uses of medical tattooing in head and neck reconstruction reaches far beyond the applications just described.

This article aims to explain the technique of tattooing the cutaneous/mucocutaneous portion of free flaps with particular emphasis on head and neck reconstruction. Several case examples where this technique has been used to improve the appearance of patients following head and neck reconstruction are provided.

Technique

Tattooing should only be considered after all surgical adjunc- tive procedures are undertaken. For example, debulking of the free flap or static slings should be performed and allowed to stabilize prior to contemplating permanent color change.

The physical technique of tattooing a free flap is no different from tattooing elsewhere. It is the same process used for decorative tattoos. However, cosmetic and decorative tattoos differ in the nature of the implanted substances used to generate a change in pigmentation. Inks are generally used in decorative tattoos whereas iron oxide dyes are used in cosmetic applications.

Prior to undertaking tattooing of a cutaneous free flap, it is important to ensure that sufficient time has passed such that the skin is well perfused and able to heal. Patients receiving chemotherapy as a component of treatment for malignancy should receive clearance from their oncologist with regards to their immune status prior to procedures that breach the skin. Herpes prophylaxis should be considered in areas that may be afflicted by the virus. Antibiotics are not normally required but may be needed on an individual basis. Indications for antibiotic therapy include compromised immune status, ‘at risk sites’ (e.g., radiotherapy or bacterial contamination) and post treatment infections.

A range of pigments are commercially available to approximate skin colors and tones. Colors may be mixed to more closely approach the desired color. A complete match is rarely possible due to changes in the surrounding skin with perfusion and sun exposure.

Local anesthetic is infiltrated to provide anesthesia if required, and to provide vasospasm which reduces oozing and bleeding during the procedure. Tattooing is performed with a mechanized needle that protrudes and retracts rapidly with each protrusion carrying some of the selected pigment through the epidermis and into the dermis. The ‘pen’ containing the needle is drawn over the surface of the area of the skin in much the same way as coloring in. Multiple passes are made over the skin with wiping in between to remove pigment left on the surface. During the treatment the skin becomes erythematous and more darkly pigmented than the surrounding area. Some swelling and bruising may occur.

A dressing is placed and changed as required though most bleeding and oozing ceases after one to two days. A thin scab forms over the surface, which peels off over ~3 weeks. The color of the skin reduces as this occurs.

Re-assessment takes place after 3 weeks and if required more pigment can be added. Additional color may be added to specific areas, or the whole flap can be retreated as required. Following the first post treatment assessment, requirements for additional color vary enormously. Darker colors persist longer than lighter ones, which are usually retreated after 1–2 years. Phagocytosis of cosmetic dyes is much greater than is seen with decorative inks.

Case Examples

Figure 1 demonstrates a 7-year-old male whose upper and lower lips were lost through a noma (gangrenous stomatitis) infection and reconstruction was performed with a radial forearm free flap to the upper lip and anterolateral thigh free flap to the lower lip. Tattooing was used to replace the color of the vermilion border of the lips. Post tattooing is demonstrated in

Figure 2 at two years following treatment. A ‘touch up’ was performed at this stage.

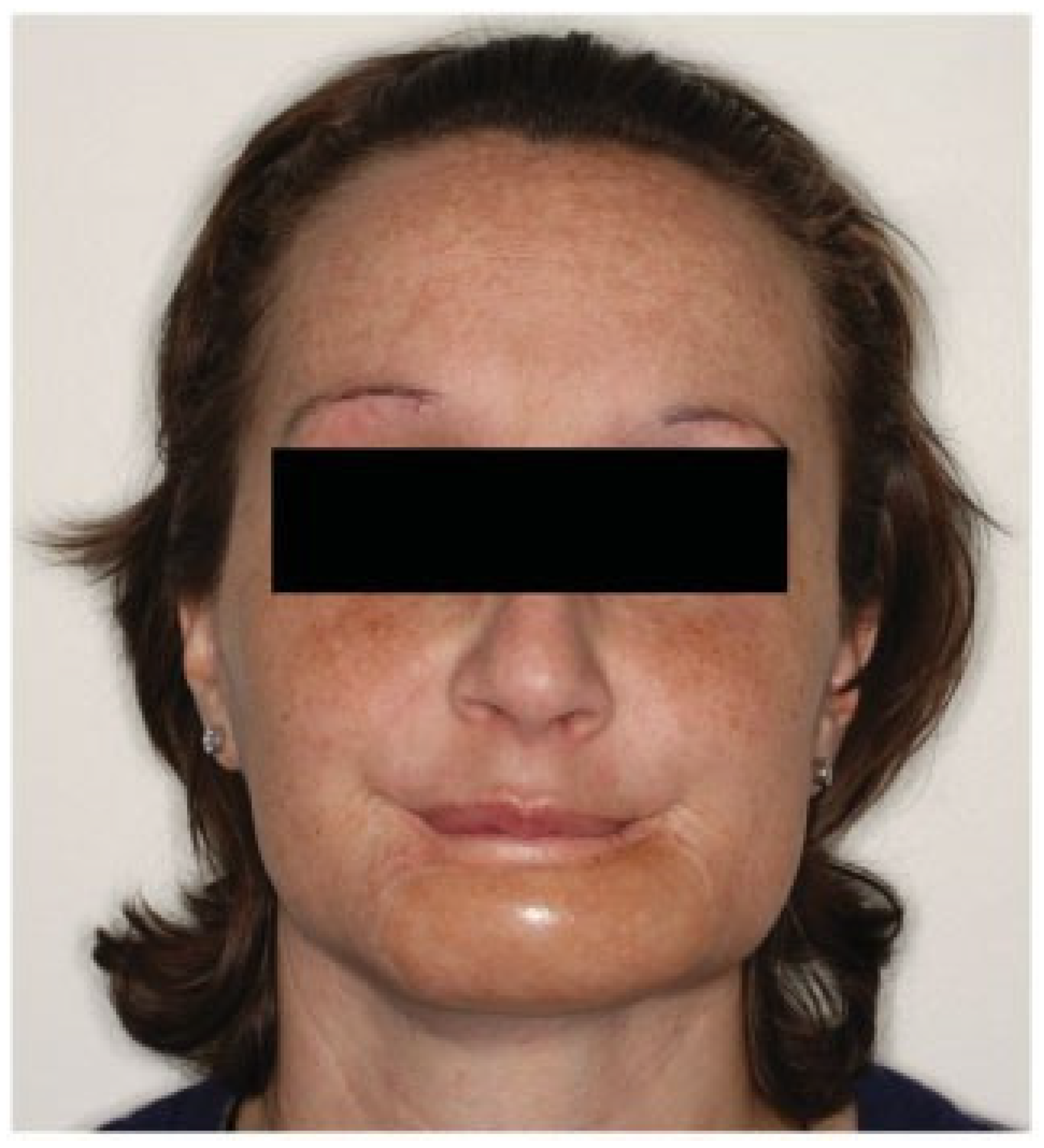

Figure 3 demonstrates a 31-year-old female who under- went an anterior mandibulectomy and skin excision for chondroblastic osteosarcoma of the mandible. Reconstruction was undertaken with a fibula free flap. Tattooing was used to improve the color of the fibula skin paddle to more closely match the surrounding skin of the face. Post tattooing is demonstrated in

Figure 4.

Discussion

Free flap reconstruction of the head and neck has revolutionized functional outcomes and is now the technique of choice for a variety of defects of multiple tissue types. Unfortunately, the stigmata of such reconstructions are frequently visible and may compromise the aesthetic outcome.

Although a variety of surgical techniques have been described to improve the appearance of mismatched skin color, all of these procedures require additional donor site morbidity and further surgical procedures. These must be undertaken in a population who have frequently had extensive health care interventions and may suffer from ‘burn out’ in terms of ongoing treatment.

Tattooing has relatively few complications. Transmission of viral diseases is prevented with strict aseptic technique and standard medical hygiene practices. Local infections may be managed with either antiviral or antibacterial medications as required. Occasionally reactions to the pigments may occur which would preclude further tattooing. These include allergic reactions and granulomas [

9].

The advantages of tattooing over other types of cosmetic procedure to improve skin color are as follows:

- -

Lack of donor site morbidity

- -

Ability to be performed without anesthesia, or with the use of local anesthesia at most

- -

Infinite variety of colors and combinations allowing multiple colors/pigments in one flap

- -

Ability to replicate blemishes/lentigenes etc.

The disadvantages are:

- -

Fading over time requiring ‘touch up’ procedures

- -

Equipment not readily available in a hospital setting

There are very few contraindications to the treatment and even if unsuccessful in achieving a complete match, usually a significant improvement is noticed.