Abstract

Frontal sinus injuries may range from isolated anterior table fractures resulting in a simple aesthetic deformity to complex fractures involving the frontal recess, orbits, skull base, and intracranial contents. The risk of long-term morbidity can be significant. Optimal treatment strategies for the management of frontal sinus fractures remain controversial. However, it is critical to have a thorough understanding of frontal sinus anatomy as well as the current treatment strategies used to manage these injuries. A thorough physical exam and thin-cut, multiplanar (axial, coronal, and sagittal) computed tomography scan should be performed in all patients suspected of having a frontal sinus fracture. The most appropriate treatment strategy can be determined by assessing five anatomic parameters including the: frontal recess, anterior table integrity, posterior table integrity, dural integrity, and presence of a cerebrospinal fluid leak. A well thought out management strategy and meticulous surgical techniques are critical to success. The primary surgical goal is to provide a safe sinus while minimizing patient morbidity. This article offers an anatomically based treatment algorithm for the management of frontal sinus fractures and highlights the key steps to surgical repair.

The frontal sinus is protected by thick cortical bone and is more resistant to fracture than any other facial bone [1]. Consequently, frontal sinus fractures ac- count for only 5 to 15% of maxillofacial injuries. How- ever, the majority of these fractures are the result of high-velocity injuries such as motor vehicle accidents, assaults, and sporting events [2,3,4,5]. Up to 66% of patients will have associated facial fractures [5]. Isolated anterior table fractures occur ~33% of the time. Combined fractures of the anterior table, posterior table, and/or the nasofrontal recess account for ~67% of frontal sinus injuries. Isolated posterior table injuries are uncommon. The hierarchy of treatment goals for repair of frontal sinus fractures includes avoidance of short- and long- term complications, reestablishment of an aesthetic facial contour, and return of normal sinus function if possible. Surgical management can be complex and controversial [2,3,4,5,6]. Long-term sequelae of frontal sinus fractures include chronic sinusitis, mucocele, mucopyo- cele, meningitis, and brain abscess. A treatment algo- rithm and surgical approach to the management of frontal sinus fractures will be presented.

Anatomy

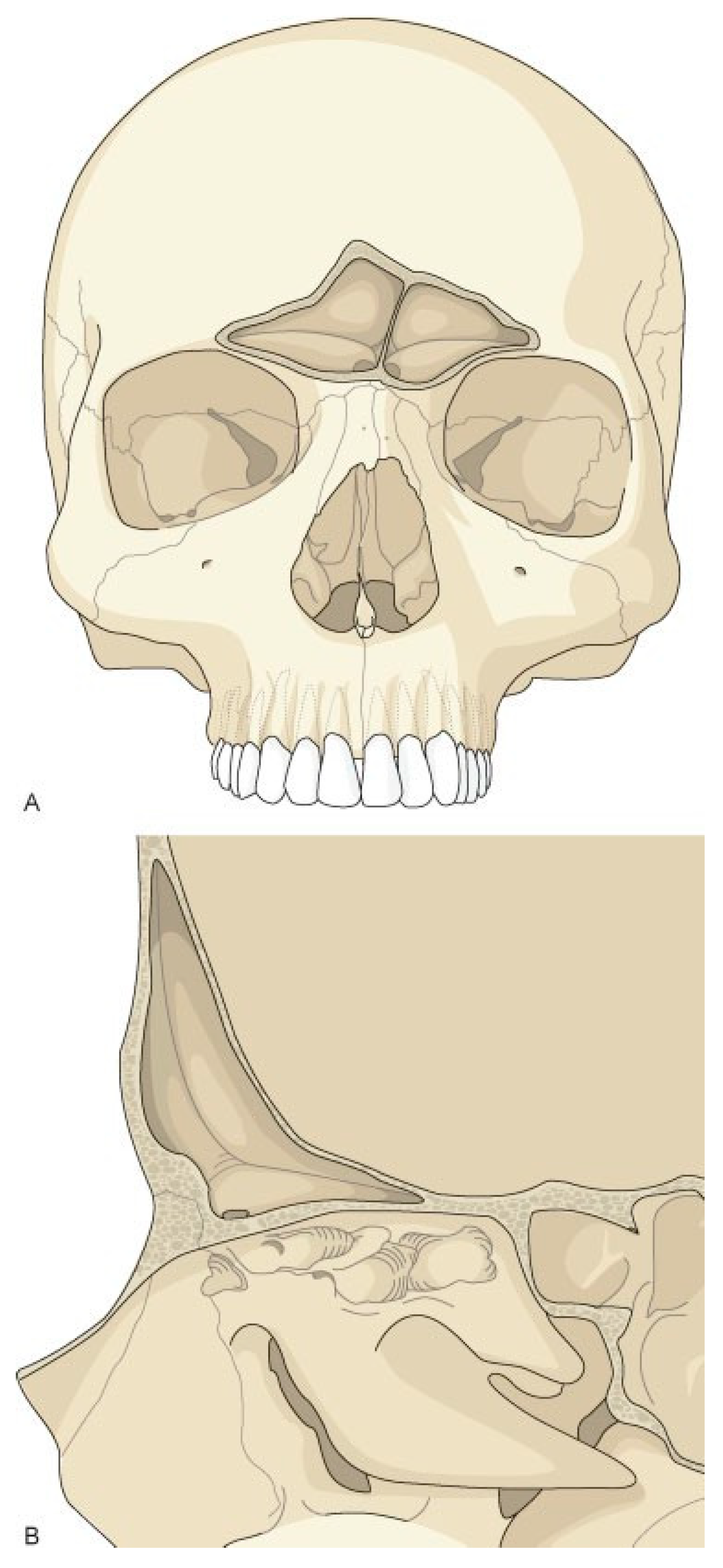

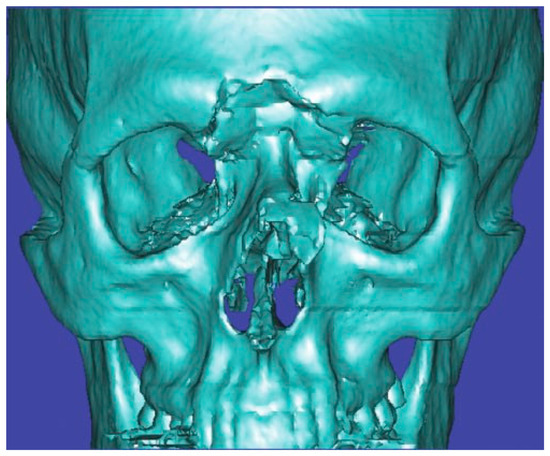

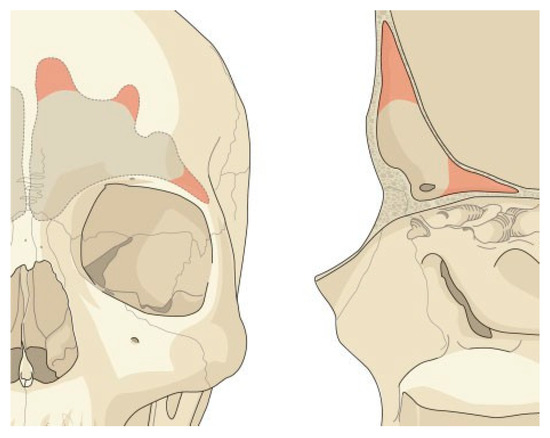

The frontal sinus is absent at birth. At 2 years of age, the anterior ethmoid air cells invade the frontal bone, and by 15 years of age, the frontal sinus is adult size. The floor of the sinus forms the medial portion of the orbital roof. The posterior table forms a portion of the anterior cranial fossa. The anterior table forms part of the fore- head, brow, and glabella (Figure 1A,B). However, the size and shape of the adult frontal sinus is highly variable. The nasofrontal recess is the sole outflow tract for the frontal sinus and is the narrowest point of an hourglass configuration. Each ostium is ~3 × 4 mm in diameter and located posteriorly, inferiorly, and medially on the floor of the sinus [7,8].

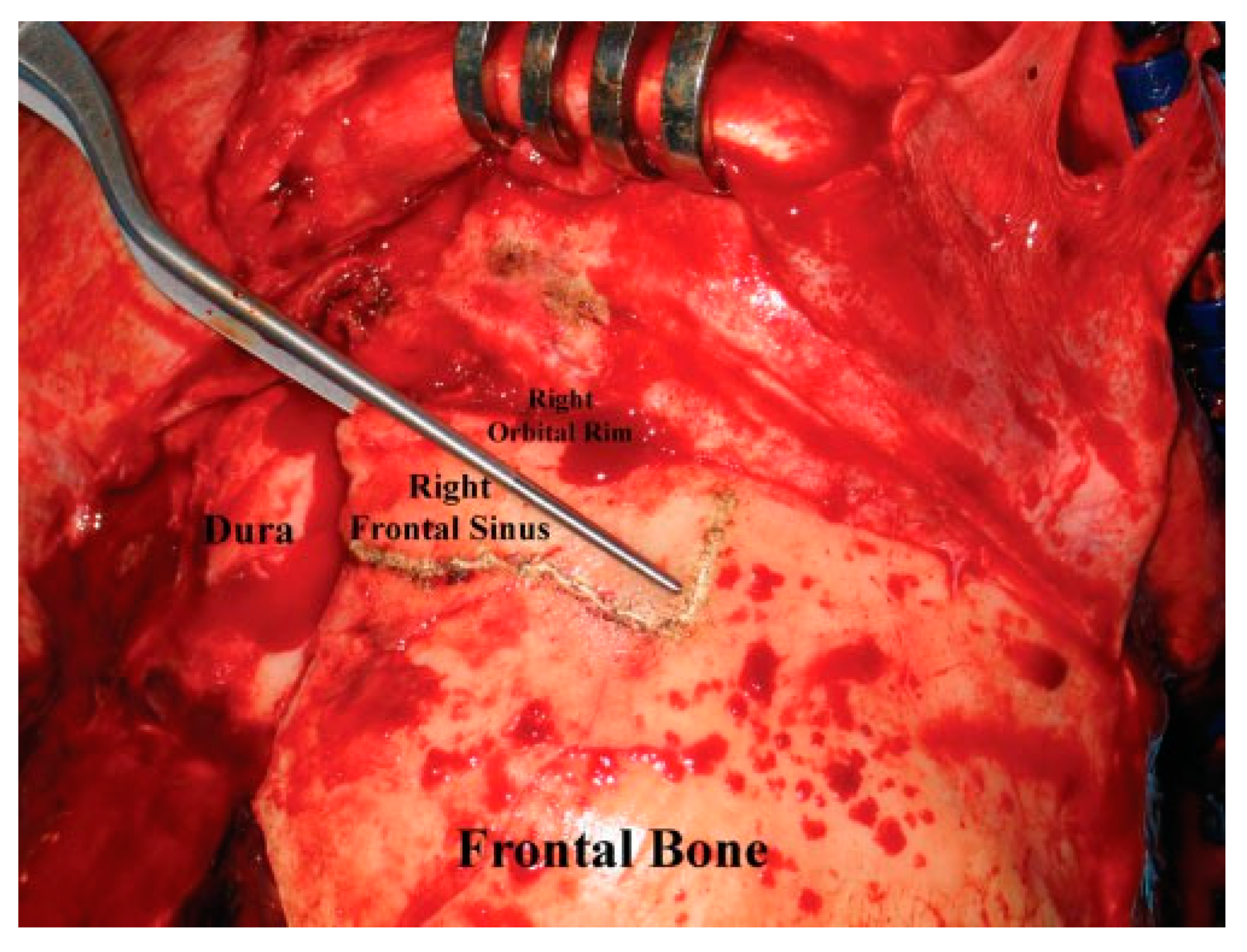

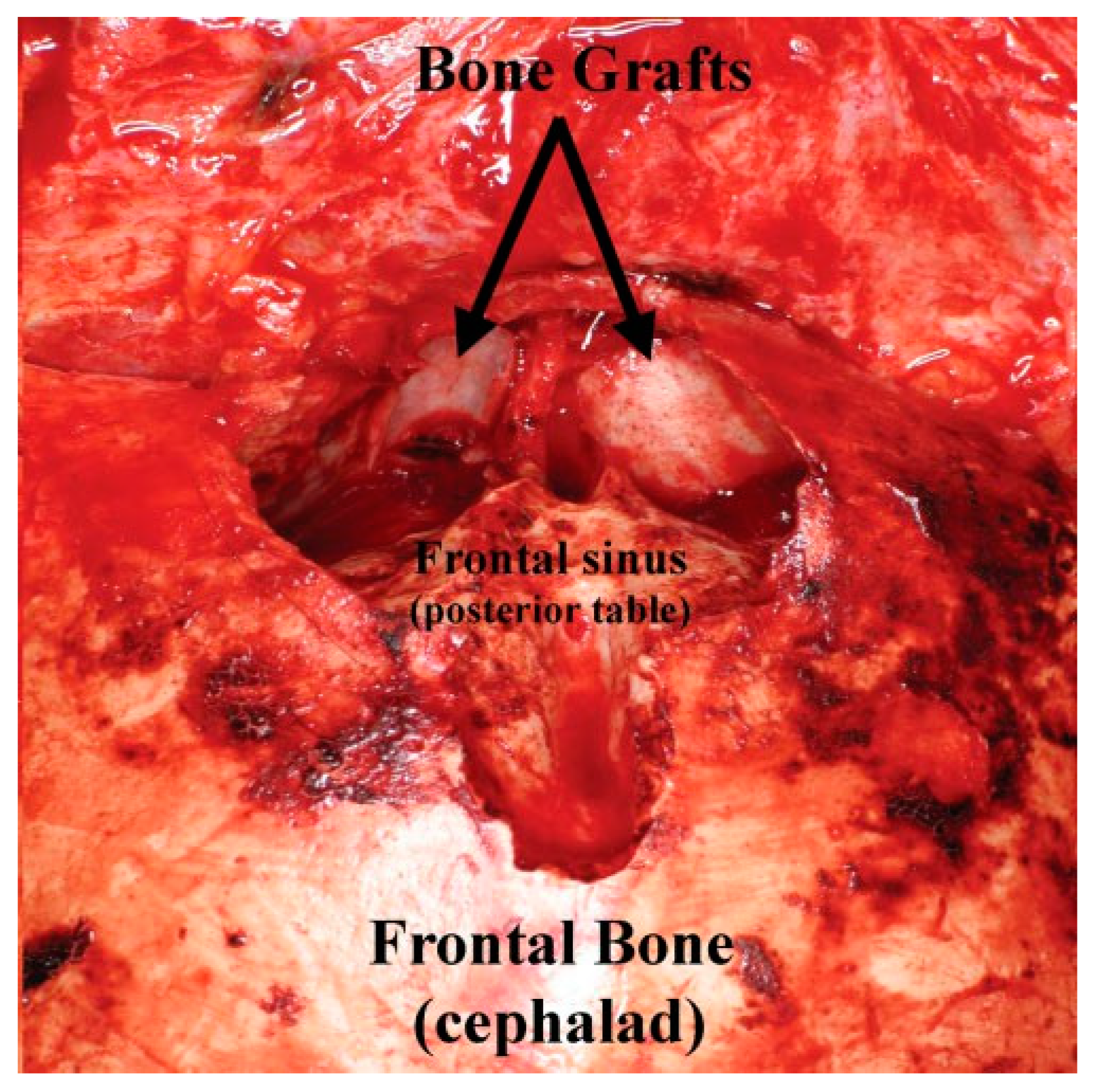

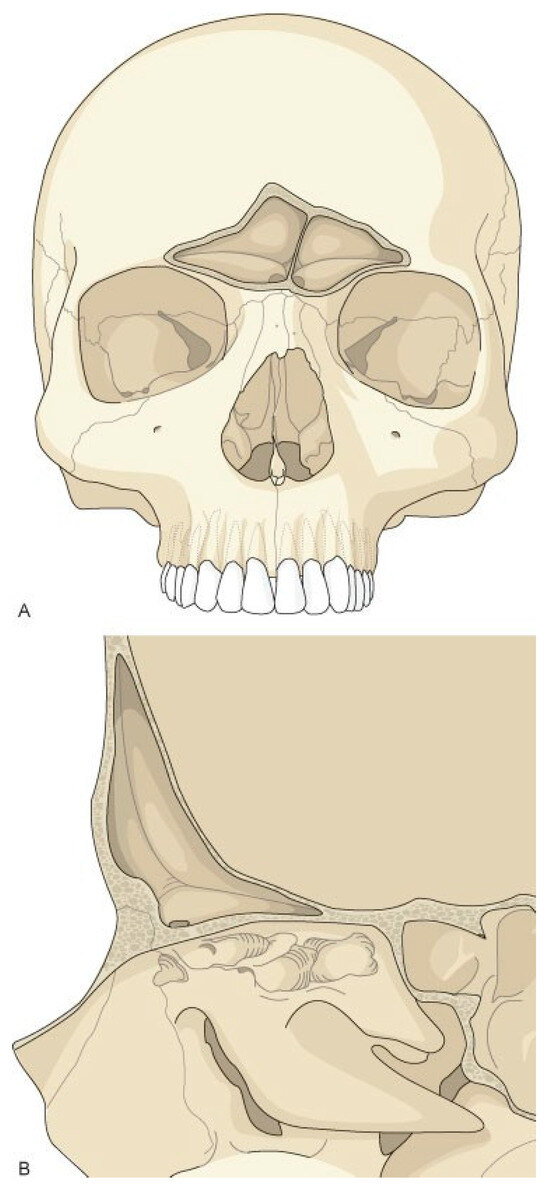

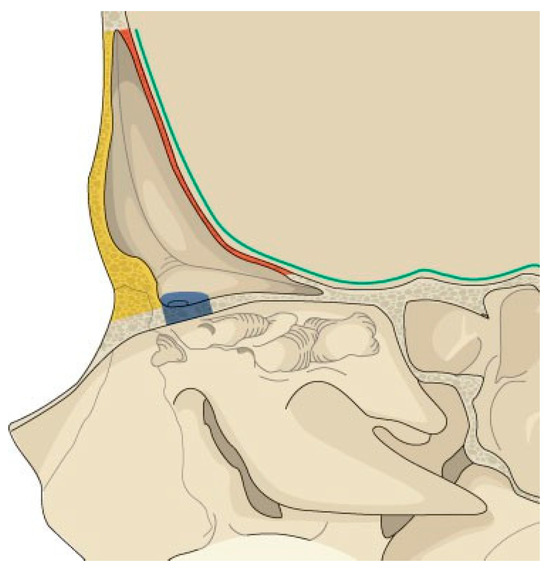

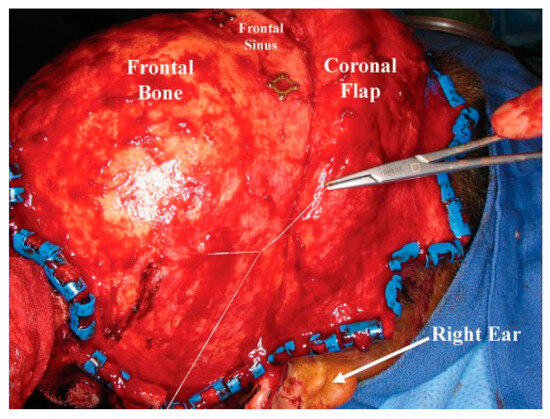

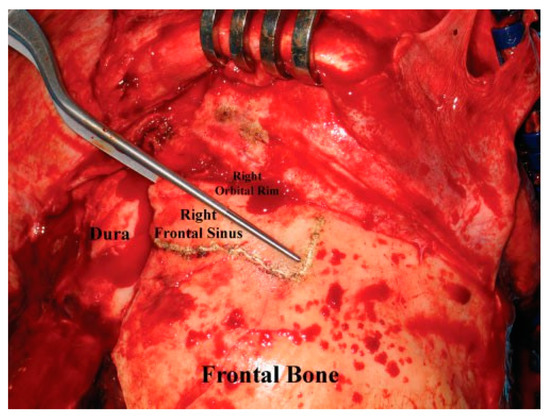

Figure 1.

Frontal sinus anatomy. The anterior table of the frontal sinus is thick bone and provides forehead contour. The posterior table is thinner and constitutes a portion of the anterior cranial fossa. The floor of the sinus makes up a portion of the orbital roof. The frontal sinus ostia is located in the medial, posterior, and inferior portion of the sinus floor.

Diagnosis

Physical Examination

The accurate diagnosis of frontal sinus injuries is crucial to the appropriate treatment. Physical findings suggestive of a frontal sinus fracture include forehead abrasions/lacerations, contour irregularities, tenderness, paresthe- sias, and hematoma. Forehead lacerations should be examined under sterile conditions to assess the integrity of the anterior table, posterior table, and dura. Through- and-through injuries of the frontal sinus have high morbidity, and prompt surgical treatment is indicated. Conscious patients should be questioned regarding the presence of watery rhinorrhea or salty-tasting postnasal drainage suspicious for a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. Drainage suspicious for CSF rhinorrhea can be grossly evaluated with a ‘‘halo test.’’ The bloody fluid is allowed to drip onto filter paper. If CSF is present, it will diffuse faster than blood and result in a clear halo around the blood. Beta-2 transferrin is the definitive test to confirm a CSF leak; however, it is generally a send-out test and takes 5 to 7 working days to get results.

Radiography

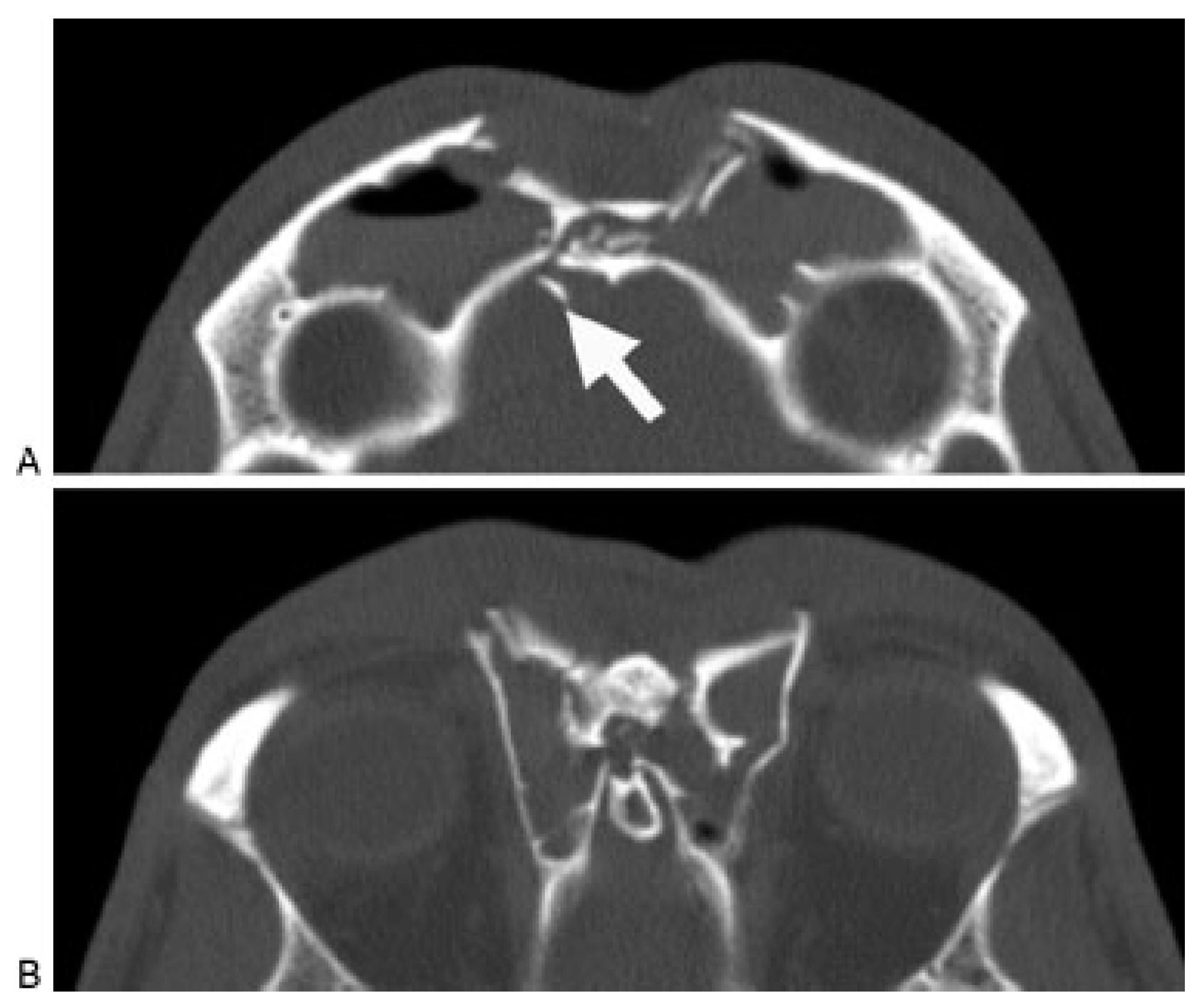

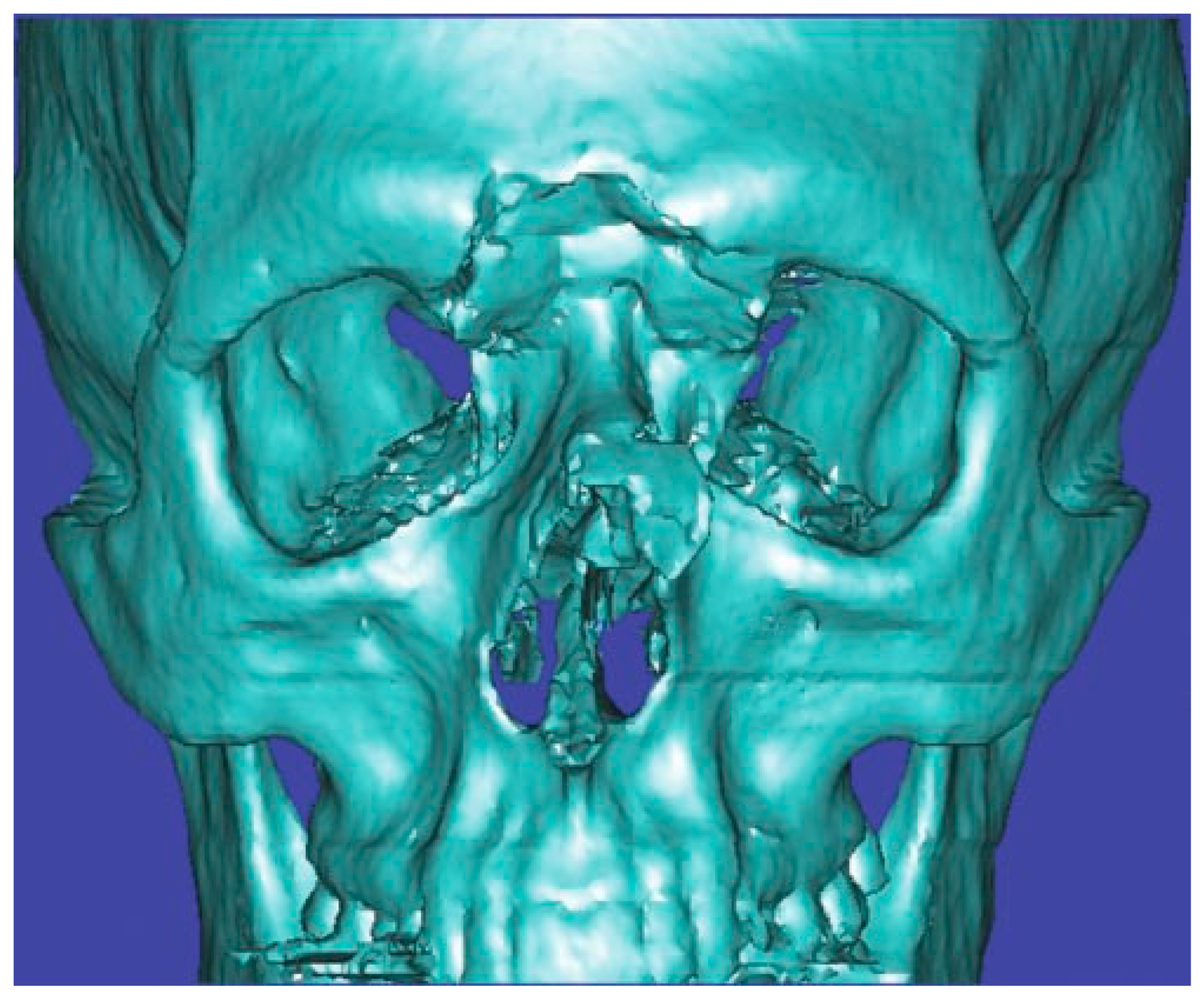

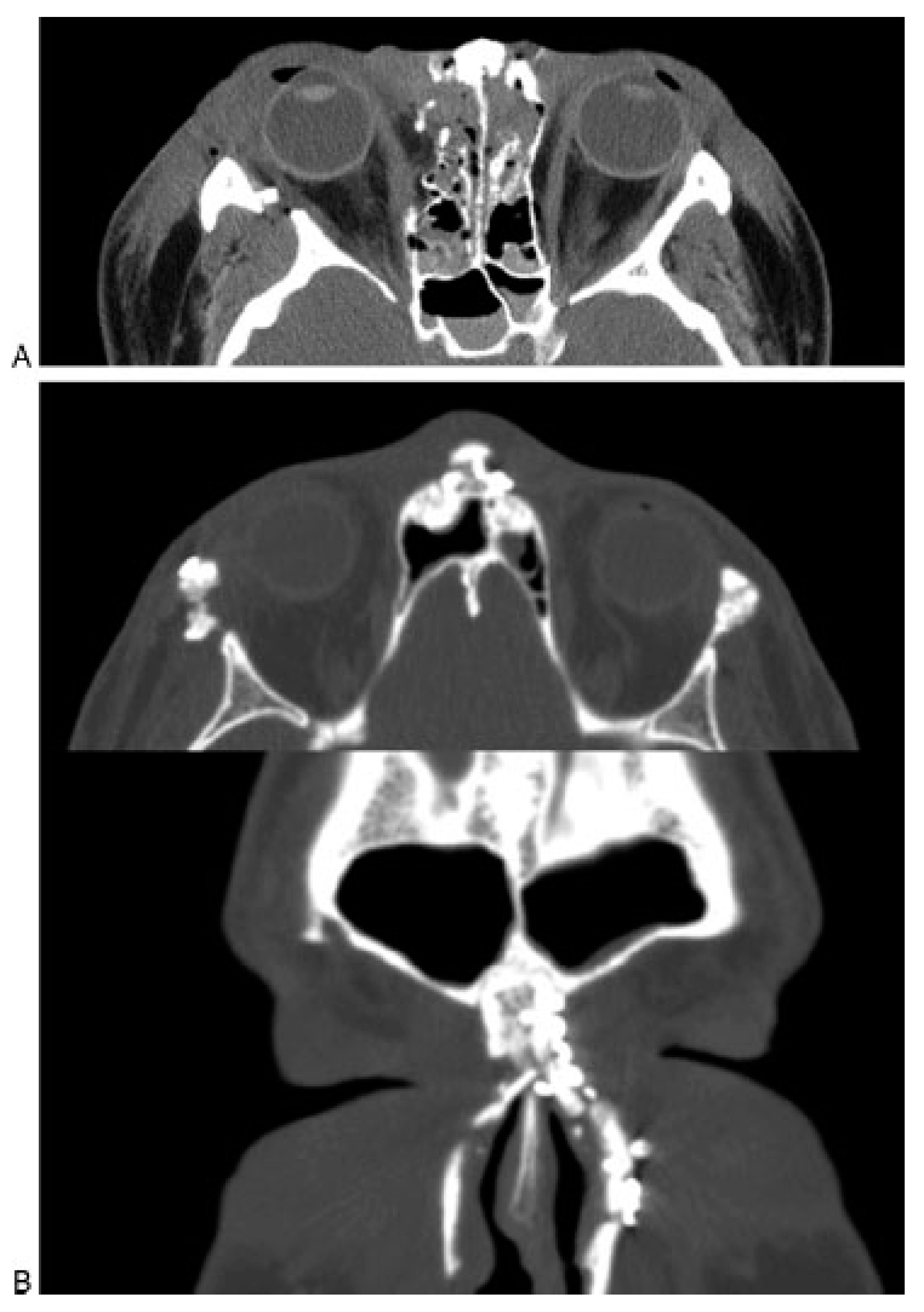

A thin-cut (1.0 to 1.5 mm) axial, coronal, and sagittal computed tomography (CT) scan is the radiological gold standard for diagnosis of frontal sinus fractures. Axial images provide the best information about the anterior and posterior tables (Figure 2); coronal images are used to assess the sinus floor and orbital roof (Figure 3). Sagittal reconstructions can be useful in assessing the patency of the frontal recess (Figure 4), and three-dimensional recon- structions may help to visualize the external contour deformity seen less clearly with two-dimensional cuts alone (Figure 5).

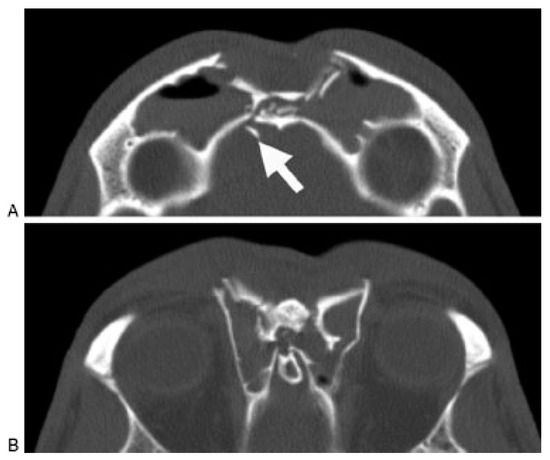

Figure 2.

Axial computed tomography scan demonstrating a frontal sinus fracture involving both the anterior and poster- ior tables. (A) Marked anterior table disruption. The white arrow points out a displaced posterior table bone fragment. (B) Disruption of the nasofrontal recess.

Figure 3.

Coronal computed tomography scan demonstrat- ing disruption of the medial orbit and frontal recess (arrows).

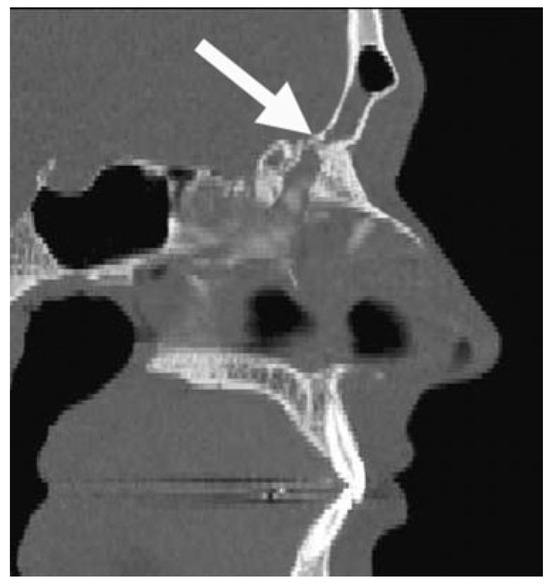

Figure 4.

Sagittal computed tomography scan demonstrat- ing a frontal sinus fracture. The arrow demonstrates narrow- ing and obstruction of the frontal sinus outflow tract.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional computed tomography scan of a frontal sinus fracture. The three-dimensional reconstruction can be helpful in delineating the location of fragments to be located intraoperatively as well as for patient/family education.

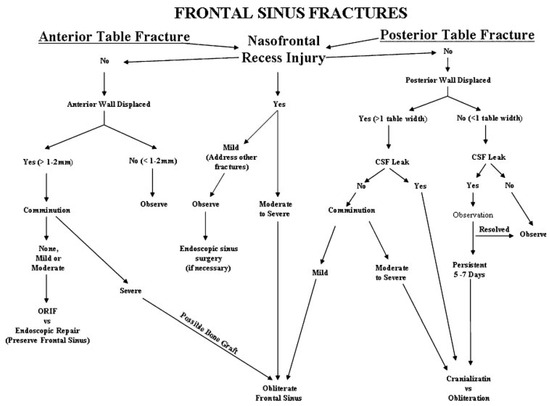

Treatment Algorithm

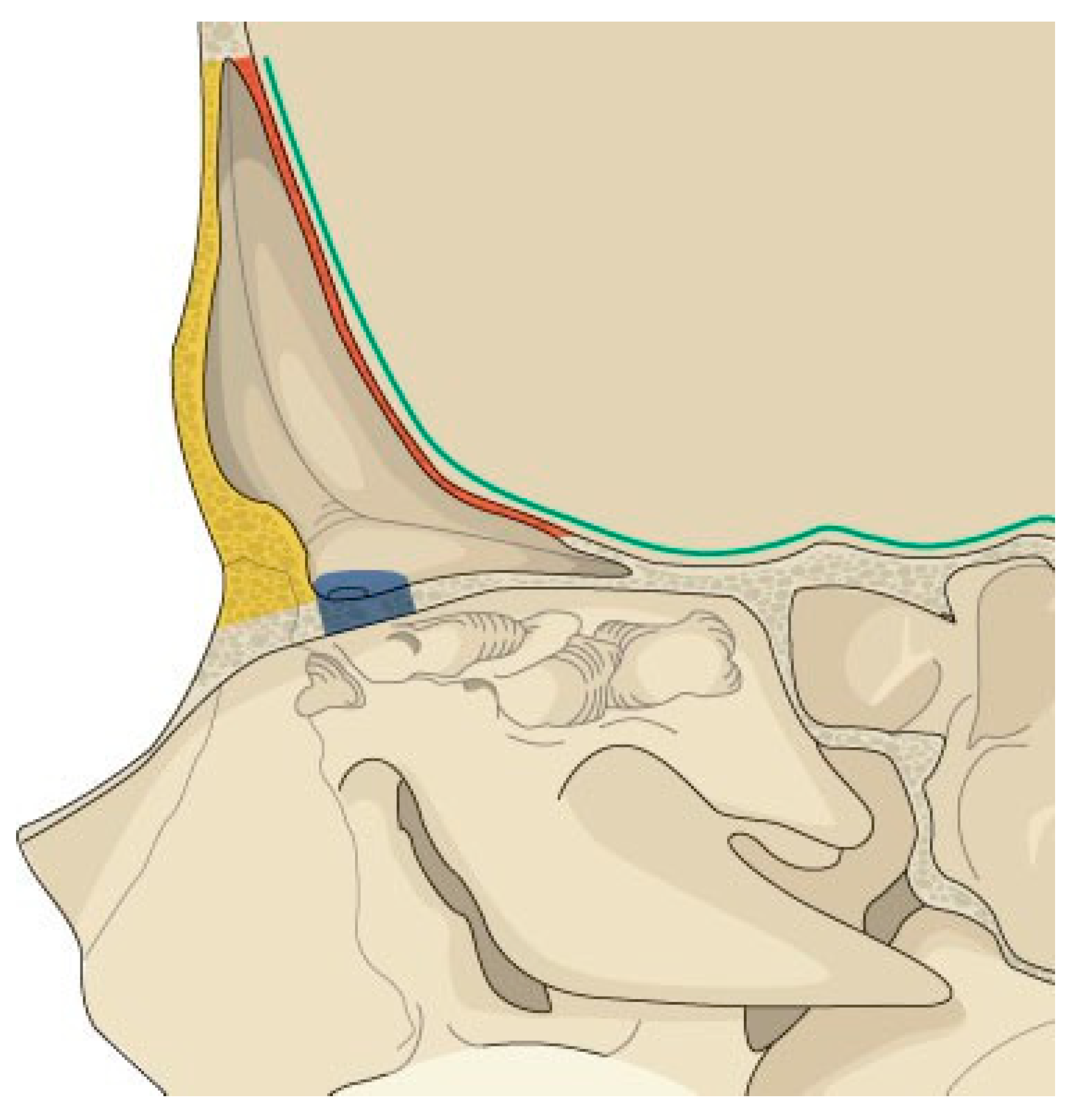

Appropriate treatment decisions for the management of frontal sinus fractures can be made by assessing five anatomic parameters (Figure 6). These parameters include the presence of: (1) an anterior table fracture, (2) a posterior table fracture, (3) a nasofrontal recess fracture, (4) a dural tear (CSF leak), and (5) fracture displace- ment/comminution. These findings can be applied to the algorithm presented in Figure 7 to determine appropriate treatment options. These options include observation, endoscopic repair, open reduction and internal fixation, sinus obliteration, sinus cranialization, and rarely sinus ablation (Reidel procedure).

Figure 6.

Illustration of the anatomic parameters that need to be assessed when developing a treatment plan for frontal sinus fractures. Yellow, anterior table; red, posterior table; blue, frontal recess; green, dural integrity.

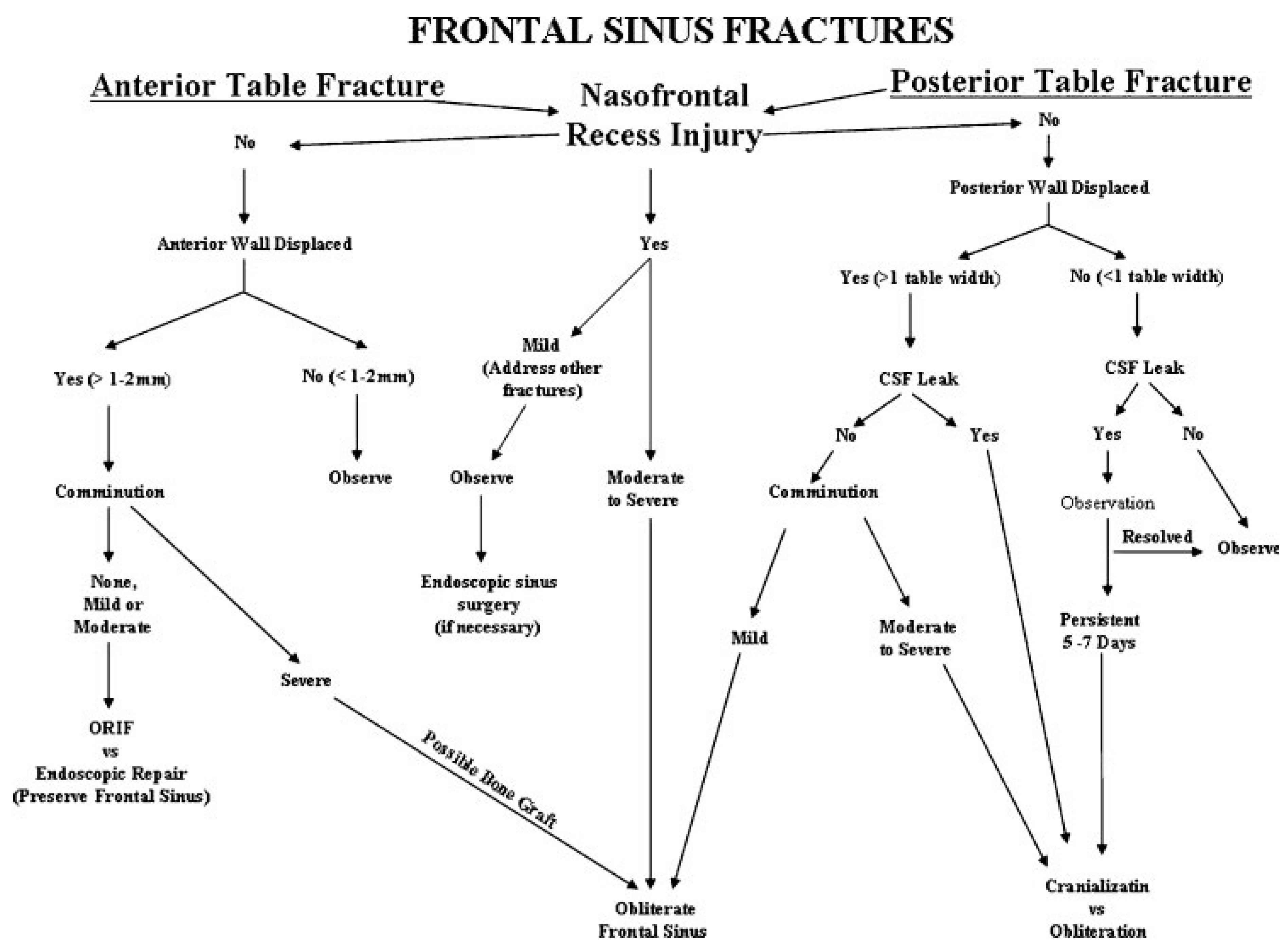

Figure 7.

Treatment algorithm for management of frontal sinus fractures. The algorithm is based on five anatomic parameters: anterior table fracture, posterior table fracture, frontal recess injury, dural integrity, and fracture comminution.

Frontal Recess Injuries (Figure 7)

Frontal recess fractures result in disruption of the only frontal sinus outflow tract. Regardless of anterior or posterior table injuries, frontal recess fractures that result in sinus outflow obstruction will generally require frontal sinus obliteration. Due to the compact nasofrontal anatomy, accurate diagnosis of a frontal recess injury on CT can be difficult to accurately assess. One option (used infrequently by the author) is to perform a frontal sinus trephination and visualize the recess endoscopi- cally. If the frontal recess patency remains in question (and there are no other significant sinus injuries), pa- tients may be followed clinically and with sequential CT scans at ~3 and 12 months to ensure that the sinus is patent and no frontal recess stenosis has occurred. Smith et al. described some success with expectant observation of frontal recess fractures. After open reduction and internal fixation of the frontal sinus anterior table and naso-orbito-ethmoid injuries, the patients were followed with serial CT scans [9]. They reported spontaneous ven- tilation of the sinus in five of seven patients. Two patients had persistent obstruction requiring an endo- scopic frontal sinusotomy. At the time of publication, these two patients had adequate sinus ventilation (21 and 25 months), and no patients had recurrent infection or mucocele formation (mean follow-up 17 months). The current author has a series of 10 patients being treated in a similar fashion and has noted no complications or need for endoscopic sinusotomy to this point (unpublished data) (Figure 8A,B). Although early reports on this tech- nique are promising, endoscopic frontal sinusotomy following frontal recess trauma can be technically chal- lenging and should be reserved for surgeons with ex- tensive experience in both endoscopic sinus surgery as well as open approaches to the frontal sinus.

Figure 8.

(A) Axial computed tomography (CT) scan of an acute frontal sinus injury, showing partial disruption of the frontal recess. (B) Postoperative axial and coronal CT scan of the same patient demonstrating resolution of mucosal edema and patency of the frontal recess. The frontal sinus injury was observed and no frontal sinusotomy was per- formed.

Anterior Table Fractures (Figure 7)

Nondisplaced (less than 1 to 2 mm) anterior table fractures can be observed with little risk of long-term morbidity. Fractures with greater displacement (2 to 6 mm) present little risk of mucocele formation; how- ever, the risk of an aesthetic deformity increases with the degree of displacement. Although a surgical repair may be necessary, the risk of alopecia from a coronal incision may result in an iatrogenic deformity more severe than the injury itself. An endoscopic repair may be indicated in this patient population. This author and others have studied endoscopic fracture reduction in the acute set- ting and found it to be technically challenging [10,11,12]. Although some authors perform endoscopic fracture repair, we currently prefer to observe these patients and endoscopically camouflage the fracture if an aesthetic deformity develops [13,14,15]. This avoids the need for a coronal incision and also allows the patient to assess the degree of deformity after all facial edema has resolved. At this point, the patient can then make an educated decision as to whether they desire surgical intervention. In the author’s experience, a significant number of patients will desire no surgical intervention. More complex anterior table fractures and those that extend below the orbital rim may require open reduction using a coronal incision. Uncommonly, frontal sinus obliteration may be required.

Posterior Table Fractures (Figure 7)

The treatment algorithm for posterior table fractures is complex due to the risk of CSF leak, meningitis, and mucocele formation [2,3,4,5,6]. The primary decision criteria for surgical intervention are the degree of fracture displacement and the presence of a CSF leak. Although the degree of displacement is subjective, the author prefers to use the width of the posterior table as a rule of thumb. It is easily defined on CT, has been used by other authors [3], and generally correlates well with the severity of injury.

Less Than One Table Width Displacement

Patients with posterior table displacement less than one table width and no CSF leak present may be observed. Long-term follow-up with repeat CT scans at 2 months and 1 year is appropriate to rule out mucocele formation. If a CSF leak is present at time of injury, 1 week of observation is indicated; ~50% will resolve spontane- ously [4]. If the leak is persistent, open reduction, dural repair, and sinus obliteration is indicated.

Greater Than One Table Width Displacement

Patients with posterior table displacement greater than one table width, no CSF leak, and only mild comminution should be considered for sinus obliteration. More severe injuries, with a frank CSF leak and moderate to severe comminution, will likely require removal of posterior table bone to repair the dural tear. If the injury or surgical repair results in disruption of more than 25 to 30% of the posterior table, sinus cranialization should be considered [16].

Surgical Technique

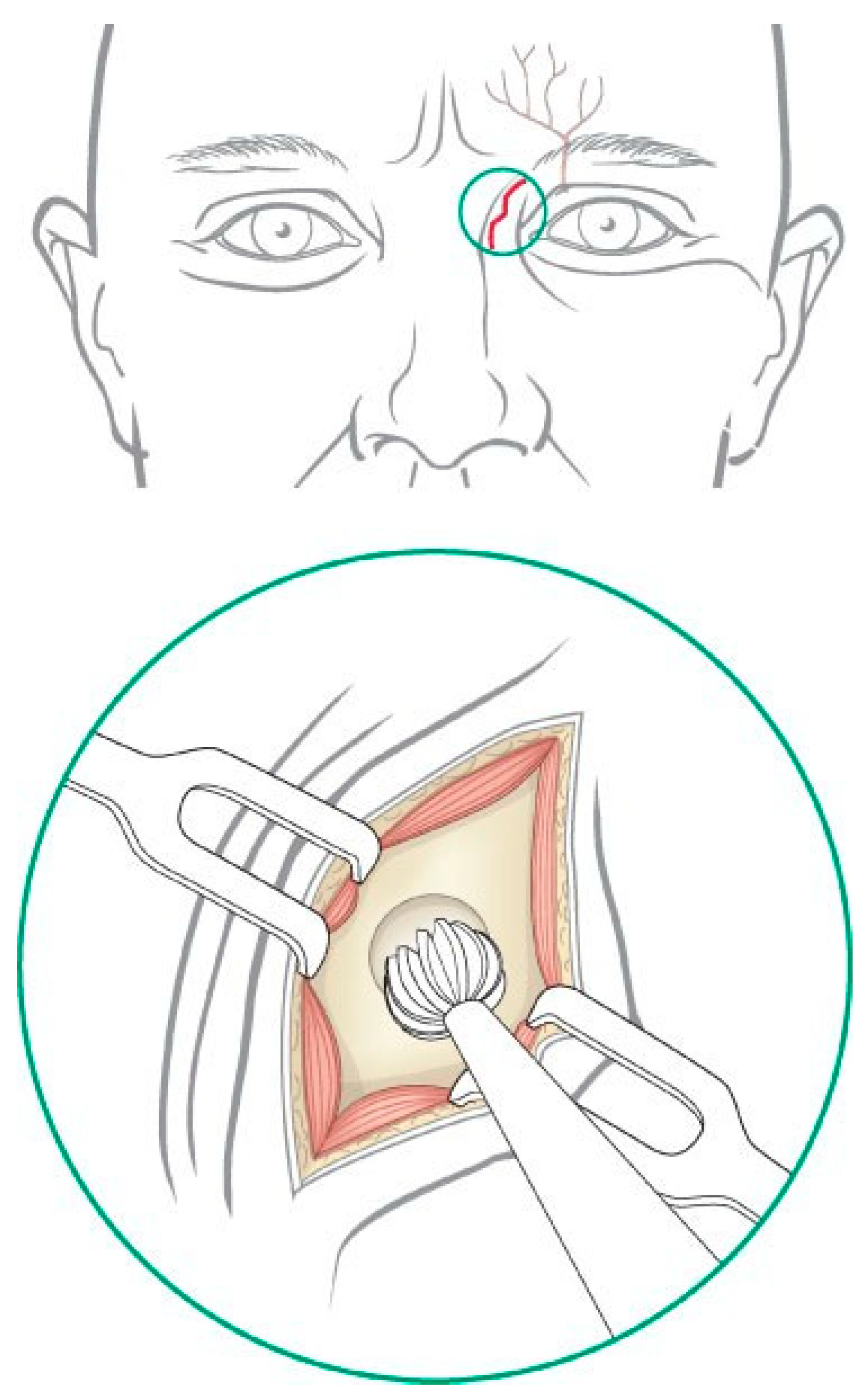

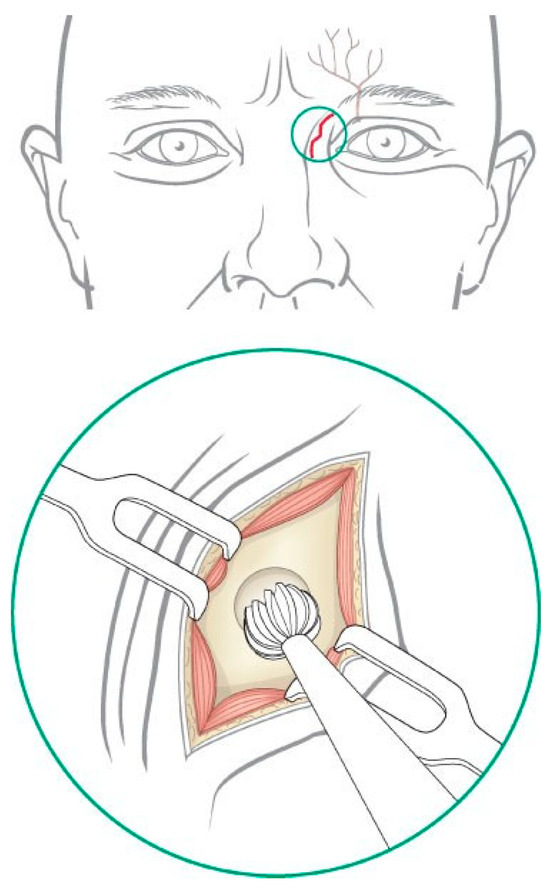

Frontal Sinus Trephination

Trephination and endoscopic visualization of the fron- tal sinus can be useful to assess the frontal recess as well as the extent of any posterior table injury. Appropriate consent is obtained for the procedure including the risks of bleeding, infection, paresthesia, and poor aes- thetic result. After infiltration of local anesthesia, a 1.0- to 1.5-cm skin incision is placed midway between the medial canthus and the glabella, ~1 cm inferior to the brow (Figure 9). The incision is best hidden by placing it inferior and deep to the curve of the forehead. A small V-shaped relaxing incision can be added to reduce the risk of scar contracture and webbing. The supratro- chlear neurovascular pedicle is located deep to the medial aspect of the brow and should be protected while the dissection is carried down to the periosteum. Although some authors have suggested placing the incision within the medial brow, this should be avoided because it places the supratrochlear neurovascular pedicle at greater risk and may result in injury to the hair follicles of the eyebrow. A guarded micropoint monopolar electrocautery can then be used to dissect through the soft tissues and onto the frontal bone. The location of the frontal sinus is confirmed on the CT scan (or with navigation if desired), and a small cutting burr is used to open a 4- to 5-mm frontal sinusotomy ~1 cm medial and inferior to the medial brow (Figure 9 inset). The mucosa is incised sharply, and the sinus can be suctioned free of any blood or mucus. The posterior table and nasofrontal recess can be examined with a 0- degree and/or 30-degree endoscope for any evidence of mucosal laceration or hematoma. A Valsalva maneuver can assist with the diagnosis of a CSF leak. Flexible pediatric bronchoscopes can be used to visualize the lateral aspects of the frontal sinus, but they are more cumbersome. Fluorescein or methylene blue have been instilled into the sinus to assess frontal recess obstruc- tion. However, dye materials make visualization of the sinus much more difficult (particularly methylene blue), and passage of the dye into the nose does not rule out the presence of a fracture or assess the long-term risk of frontal recess stenosis. The author does not recommend this technique. Once the examination has been com- pleted, the skin and soft tissue are closed meticulously in layers.

Figure 9.

Incisions used for trephination of the left frontal sinus. Caution must be used to avoid injury to the supratro- chlear neurovascular pedicle.

Endoscopic Anterior Table Repair

This technique is used for isolated anterior table frontal sinus fractures above the orbital rim. The repair is generally performed 2 to 4 months after the injury when all forehead swelling has resolved. If the patient is seen acutely, the reasoning and indications for a delayed repair must be explained (i.e., observation to confirm that an aesthetic deformity is present and the fact that an endoscopic repair can avoid a coronal incision). It should be articulated to the patient that a traditional open reduction cannot be performed secondarily. Although the risk of mucocele formation is very low, this should be discussed as well. Prior to surgery, appropriate consent is obtained for the procedure including the risks of bleeding, infection, paresthesias, alopecia, poor aesthetic result, and possible need for open approach if an endo- scopic repair cannot be performed.

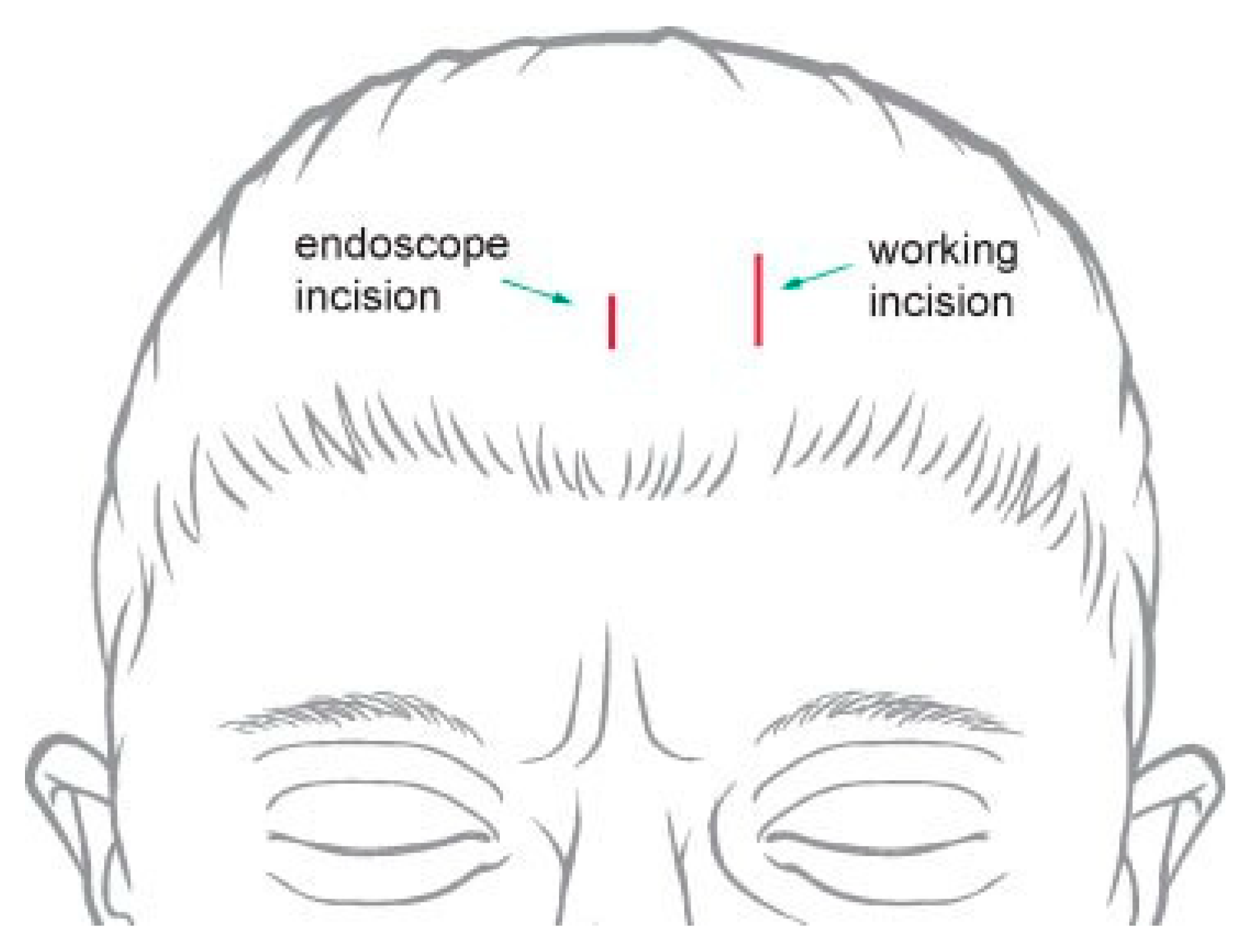

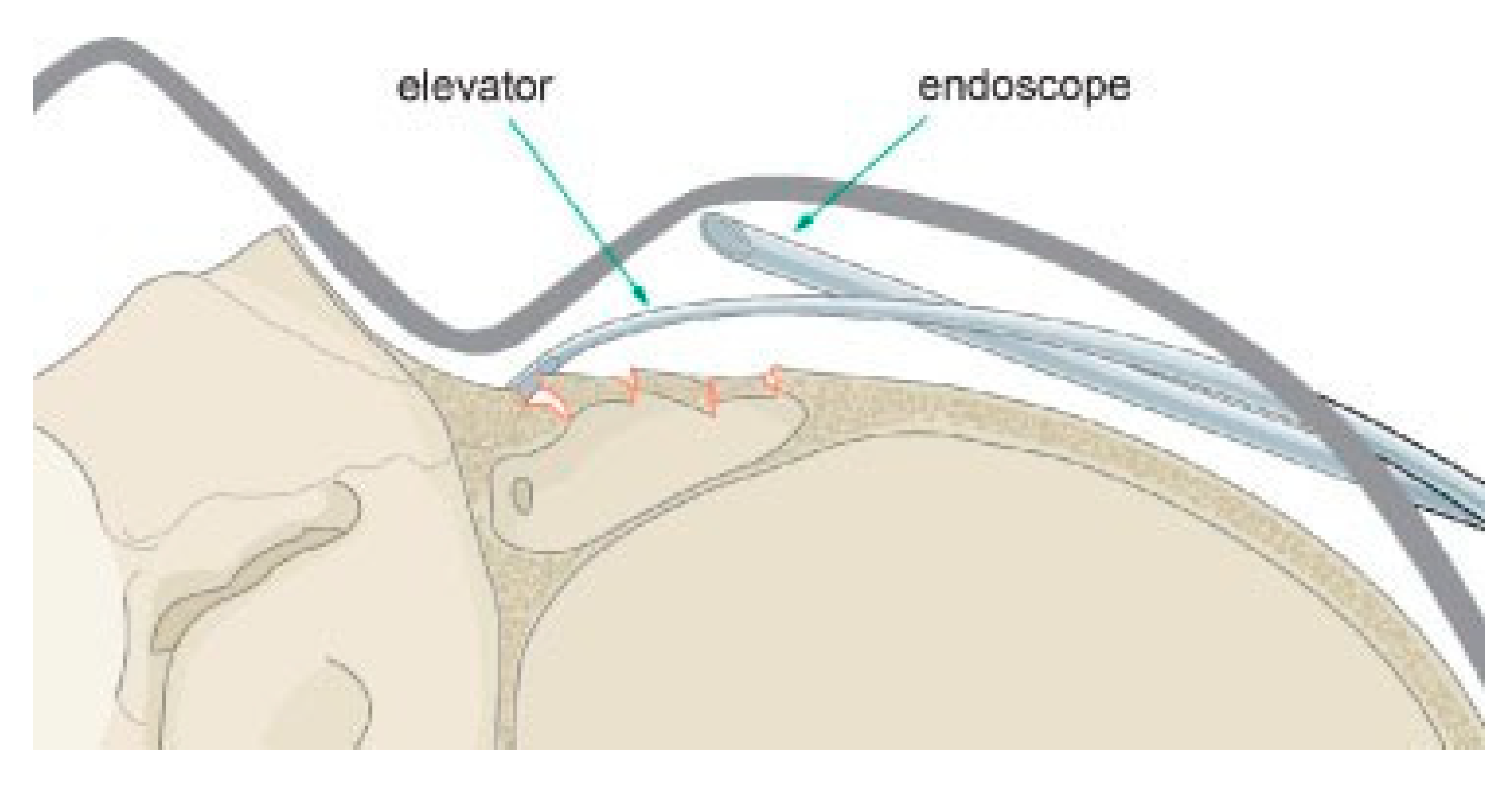

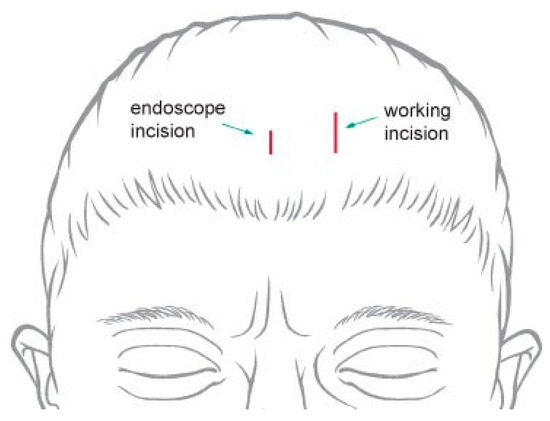

The surgical technique is similar to a brow lift [17]. A 3- to 5-cm parasagittal ‘‘working’’ incision should be placed above the fracture, 3 cm behind the hairline and carried through the periosteum onto bone (Figure 10). Local vasoconstriction agents should be used liberally when possible, and electrocautery should be avoided to reduce the risk of hair follicle injury. The incision length should be kept to a minimum, but this will vary depend- ing on the size of the fracture and implant to be inserted. A 1- to 2-cm subperiosteal ‘‘endoscope’’ incision is then placed at the same height, 6 cm medial to the working incision. In patients with a prominent forehead or receding hairline, the incisions may need to be closer to the hairline to allow visualization around the forehead curvature.

Figure 10.

Incisions used for endoscopic approach to the frontal sinus. The lateral ‘‘working incision’’ is larger and used for passing instrumentation and the implant. The medial incision is smaller and used to insert the endoscope.

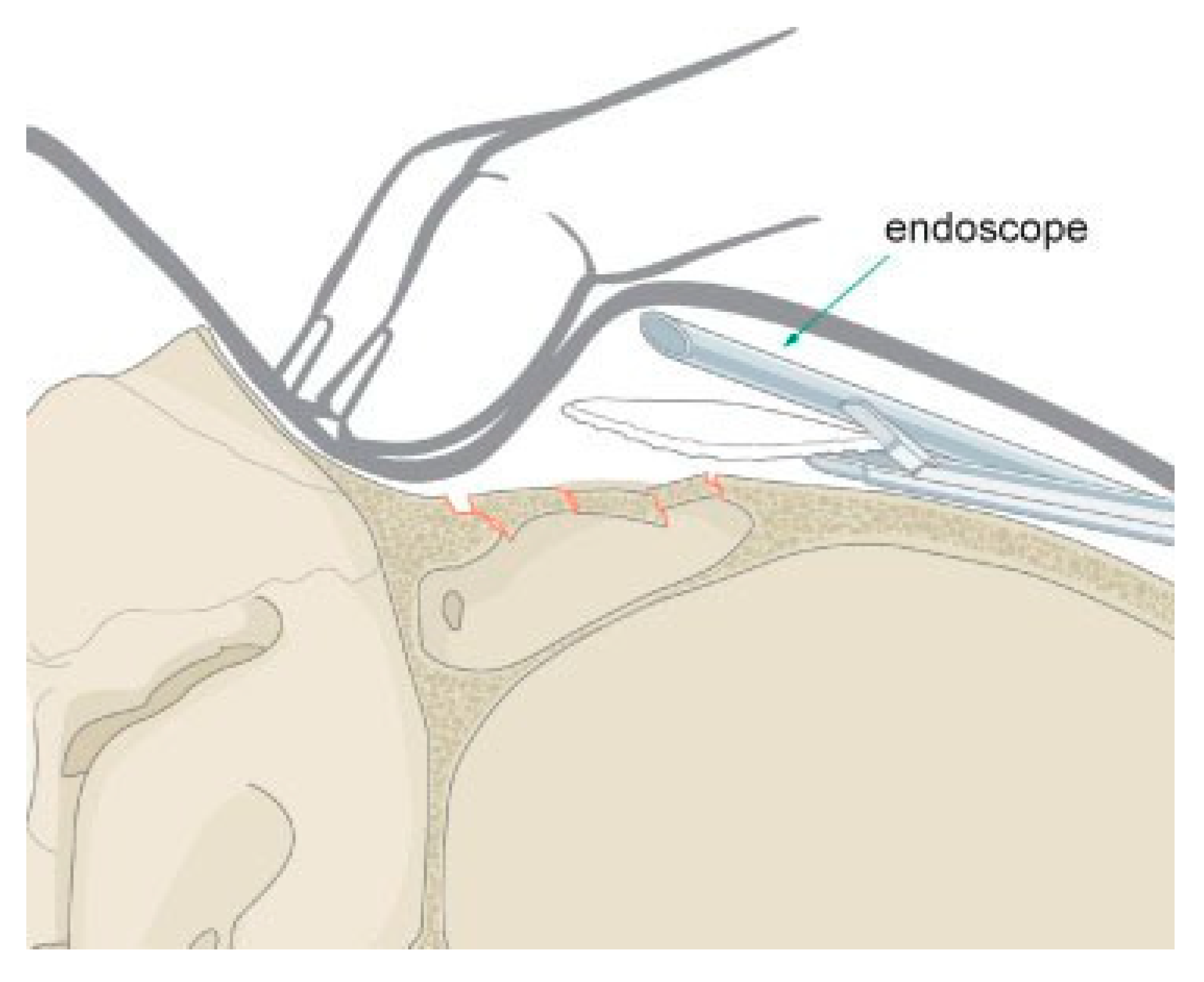

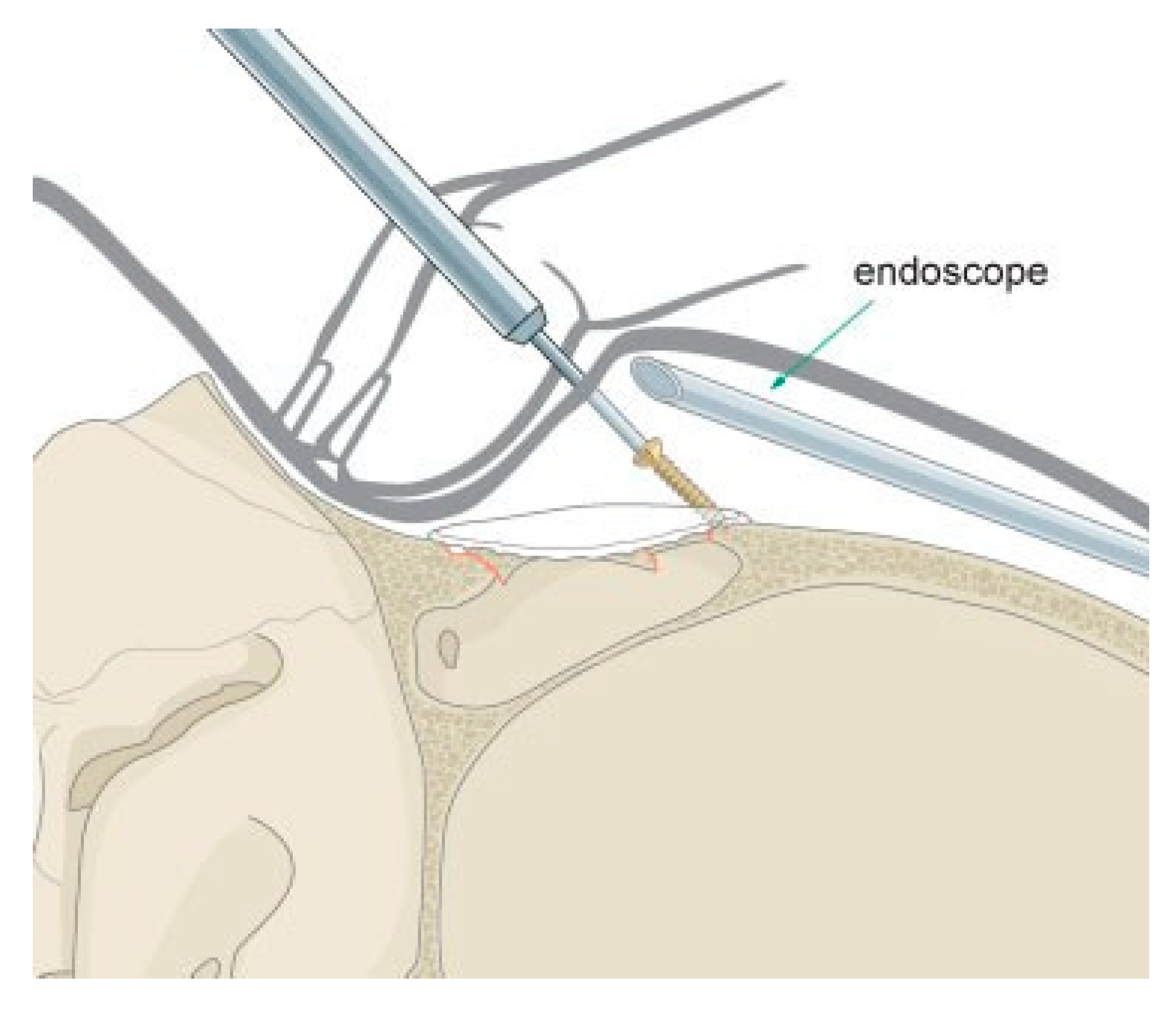

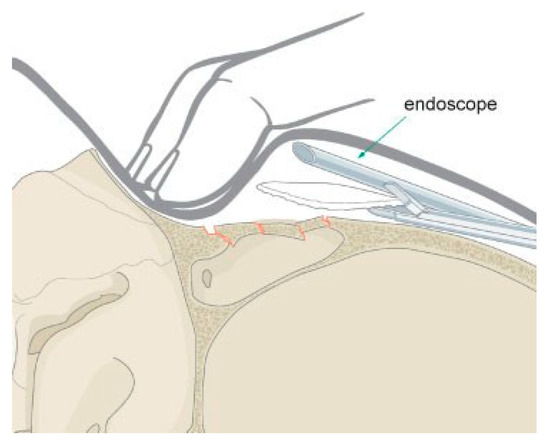

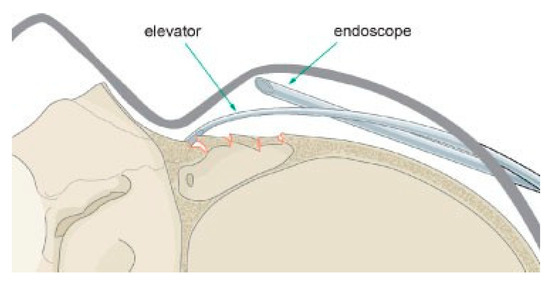

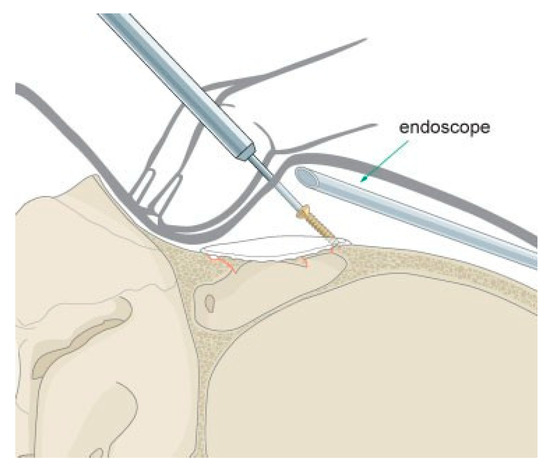

Using an endoscopic brow lift elevator and exter- nal palpation, a directed subperiosteal dissection is performed down to the level of the fracture. A 4.0- mm, 30-degree endoscope (with rigid endosheath and camera) is inserted through the endoscope incision to visualize the fracture. A large endosheath guard is recommended to maintain a generous optical cavity. The periosteum is then carefully elevated over the defect (Figure 11). Because the fracture has healed, there is little risk of entry into the sinus. The supraorbital and supra- trochlear neurovascular pedicles are commonly visual- ized at the orbital rim. Caution should be used to avoid excessive traction, which can result in postoperative paresthesias. Once the limits of the fracture have been visualized, a 0.85-mm-thick porous polyethylene sheet is trimmed to approximate the defect. The superior edge is then marked with a pen to maintain the orientation endoscopically during insertion. The implant is inserted through the working incision and manipulated both internally (with instruments) and externally (with fin- gers) over the defect (Figure 12). Once the implant is in place, the size and shape are evaluated endoscopically and the implant is removed, trimmed, and refined. The process is repeated until the diameter of the implant approximates the defect. At times, the author has su- tured two to three layers of porous polyethylene sheeting together in an inverted pyramid shape to more accurately fill deeper defects. Once the implant is appropriately fashioned, a 25-gauge needle is passed through the skin over the fracture and endoscopically visualized to deter- mine the best site for a percutaneous incision and screw placement. Optimal incision placement will allow screws to be placed on either side of the implant through a single incision (larger implants may require two stab incisions). Once the site has been determined, a No. 11 blade is used to make a 2-mm, through-and-through stab incision. A 1.7-mm self-drilling screw (length 4 to 7 mm) is passed through the stab incision, through the edge of the implant, and into stable bone peripheral to the fracture edge (Figure 13). The screw must be securely attached to the screwdriver to avoid dislodging the screw as it passes through the soft tissue. The screw must be placed ~1.0 mm away from the implant edge or the implant may tear. If the implant remains unstable after the first screw, a second screw is placed on the contrala- teral side. The scalp incisions are then closed in layers and a pressure dressing is applied.

Figure 12.

Endoscopic insertion of a porous polyethylene implant to camouflage a frontal sinus fracture.

Figure 11.

Endoscopic exposure of a frontal sinus fracture.

Figure 13.

Transcutaneous fixation of an endoscopically placed anterior table porous polyethylene implant. Self- drilling screws are used to avoid the need for a drill.

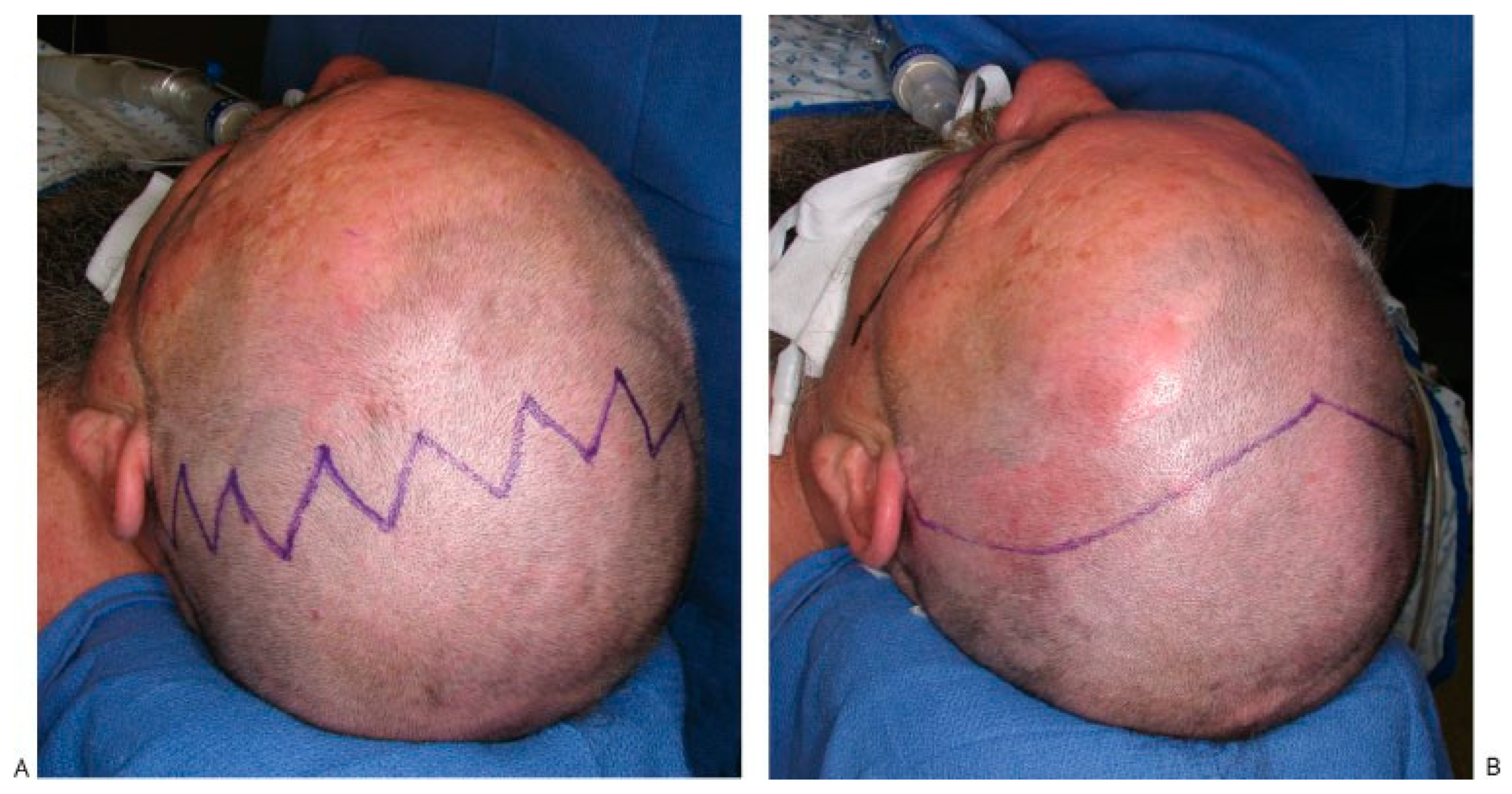

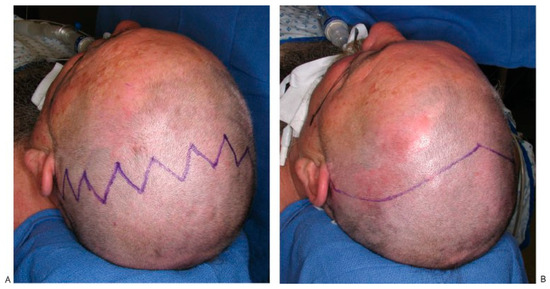

Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

Anterior table fractures that cannot be observed or managed endoscopically may require open reduction and internal fixation. The patient gives consent for the procedure and is informed of the risks of bleeding, infection, paresthesia, headache, CSF leak, orbital in- jury, diplopia, meningitis, external deformity, and late mucocele formation. In patients with longer hair (at least 3 to 4 cm), the author prefers a zigzag incision placed 4 to 6 cm behind the hairline (Figure 14A). Postoperatively when the patient is upright, the zigzag pattern allows gravity to pull the hair down and cover the transverse arms of the scar. If the patient wears very short hair, a zigzag pattern only lengthens and accentuates the in- cision. In this situation, the traditional straight line, coronal incision works equally well and is easier to perform (Figure 14B). If a straight-line incision is used, some type of marker should be placed along the incision (i.e., widow’s peak, methylene blue tattoo, etc.) to assist with symmetric closure of the scalp. In patients with male pattern baldness, the incision can be moved poste- riorly to camouflage it within in the hair. This will necessitate a slightly more extensive lateral dissection to allow forward rotation of the scalp flap. Forehead lacerations should be used to assist with the repair, but mid-forehead, brow, and ‘‘gull wing’’ incisions should be avoided due to the prominent scar and associated fore- head anesthesia.

Figure 14.

(A) Typical zigzag coronal incision used when patients have longer hair that will fall down across the incision lines. (B) Traditional widow’s peak coronal incision used in patients with shorter hair.

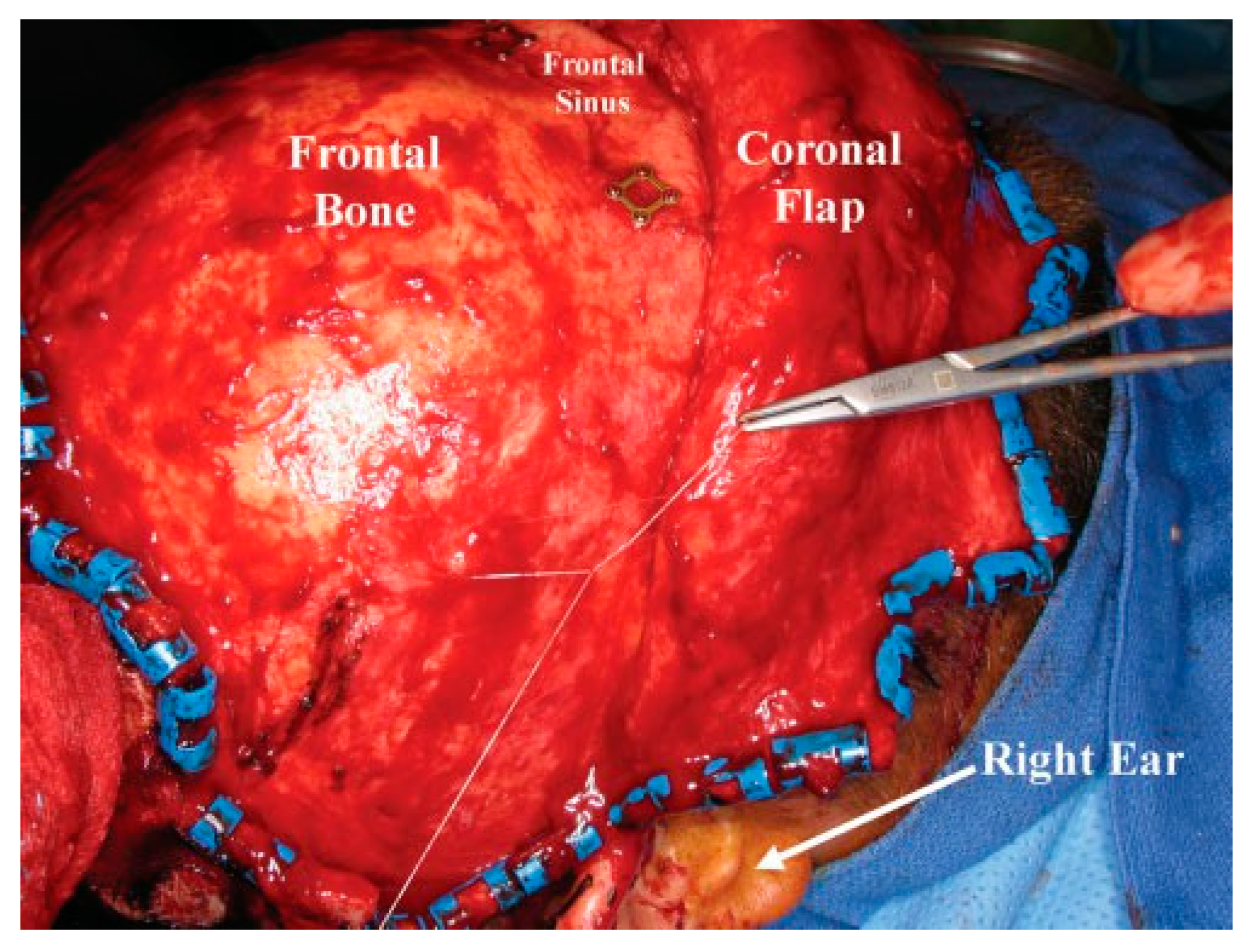

In the operating room, the bed is turned 180 degrees away from anesthesia equipment, and corneal shields or temporary tarsorrhaphies are placed. The hair need not be shaved, but patients with longer hair will require banding to delineate the incision line. Applica- tion of a water-based lubricant to the hair facilitates separating the hair and rapid application of the rubber bands. Surgical towels are stapled to the scalp just behind the incision line. An adherent plastic suction pouch is applied at the leading edge of the towel to collect blood and minimize spillage.

The greatest blood loss occurs with the initial incision and wound closure. When possible, generous amounts of a vasoconstrictor agent should be injected in a subgaleal plane prior to surgery. The skin and sub- cutaneous tissue is then incised from one temporal line to the other. Two double-prong skin hooks are used to retract the scalp away from the skull and protect the underlying pericranium from injury. Once the galea aponeurosis is incised, air will rapidly enter into the subgaleal space, developing an excellent dissection plane. Bleeding from larger vessels should be tied off individ- ually. Electrocautery should be used sparingly to avoid injury to hair follicles. Rainey clips can be used for hemostasis depending on surgeon preference.

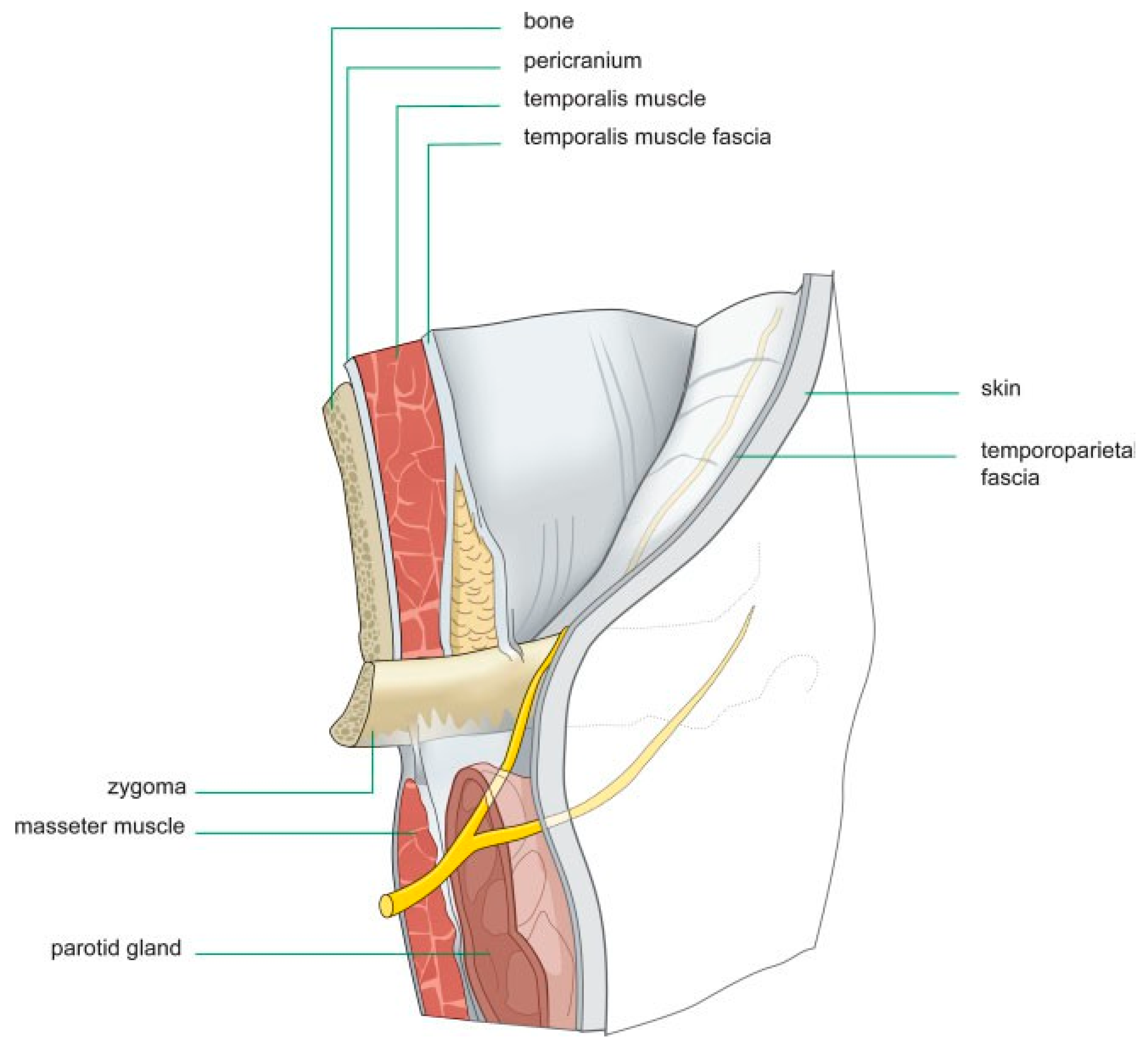

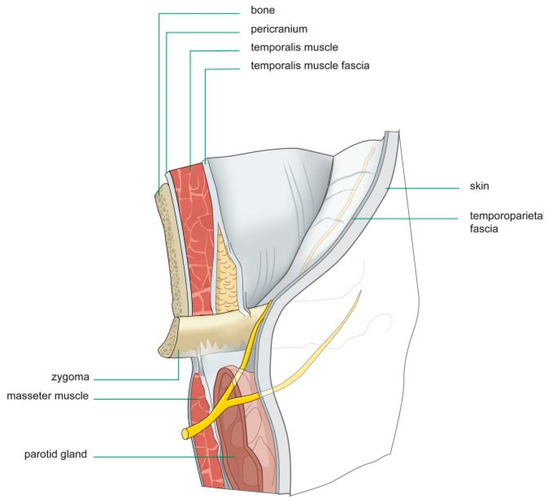

The lateral scalp dissection demands a thorough understanding of the temporal anatomy. The initial incision is carried below the temporal line and behind the helix on one side (Figure 15). The incision should be carried through the temporoparietal fascia (superficial temporal fascia) and onto the temporalis muscle fascia (deep temporal fascia), traversing the temporal artery and vein, which should be controlled using a suture ligature or Rainey clips. The appropriate depth can be confirmed by placing a small (1- to 2-mm) nick in the temporalis muscle fascia and confirming the presence of dark red temporalis muscle beneath. The flap is then elevated anteriorly using blunt finger dissection or gauze, with limited use of the scalpel. The integrity of the temporoparietal fascia must be maintained, as it contains the frontal branch of the facial nerve (Figure 15). As the temporal flap is elevated, it is joined with the central dissection by sharply incising the fibers along the tem- poral line. Once again, special attention must be used to avoid injury to the temporal nerve.

Figure 15.

Illustration of a right temporal dissection via a coronal approach. The surgeon must be very familiar with the anatomic layers of the temporal scalp to avoid injury to the temporal branch of the facial nerve.

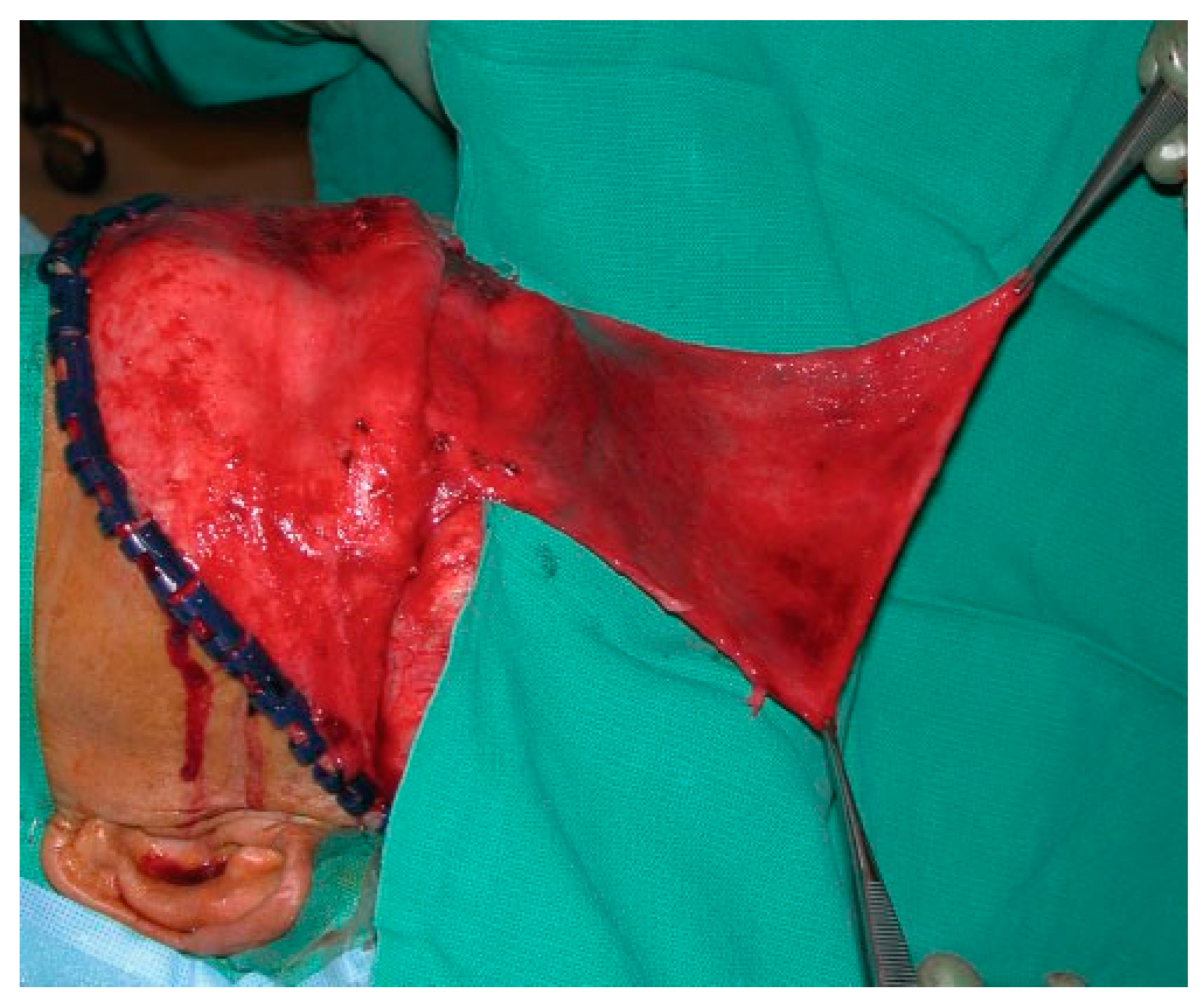

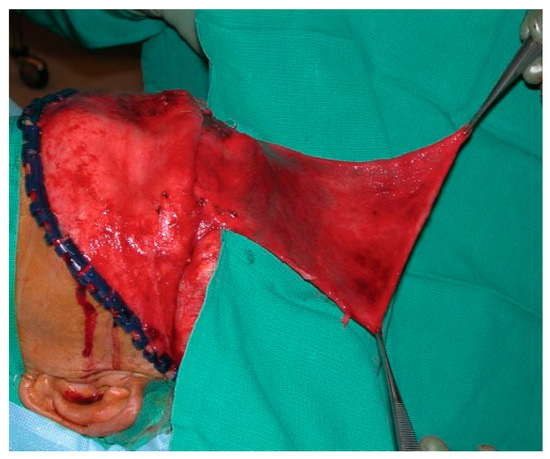

The scalp is then rotated forward, and blunt or sharp dissection can be used to elevate the subgaleal flap to a level 3 to 4 cm above the orbital rims. Care is taken to avoid injury to the supraorbital and supratrochlear neurovascular pedicles. The pericranial flap is then incised parallel and 2 cm behind the initial scalp incision. Two lateral incisions are placed 2 cm cephalad to the temporal line, which allows elevation of the pericranial flap over the orbital rims. Although periosteal lacerations may exist at the fracture site, a careful dissection will usually maintain an intact vascular supply and provide a lengthy flap that can be used for repair of unanticipated CSF leaks or obliteration of the sinus if it is small (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Intraoperative photo of a large pericranial flap.

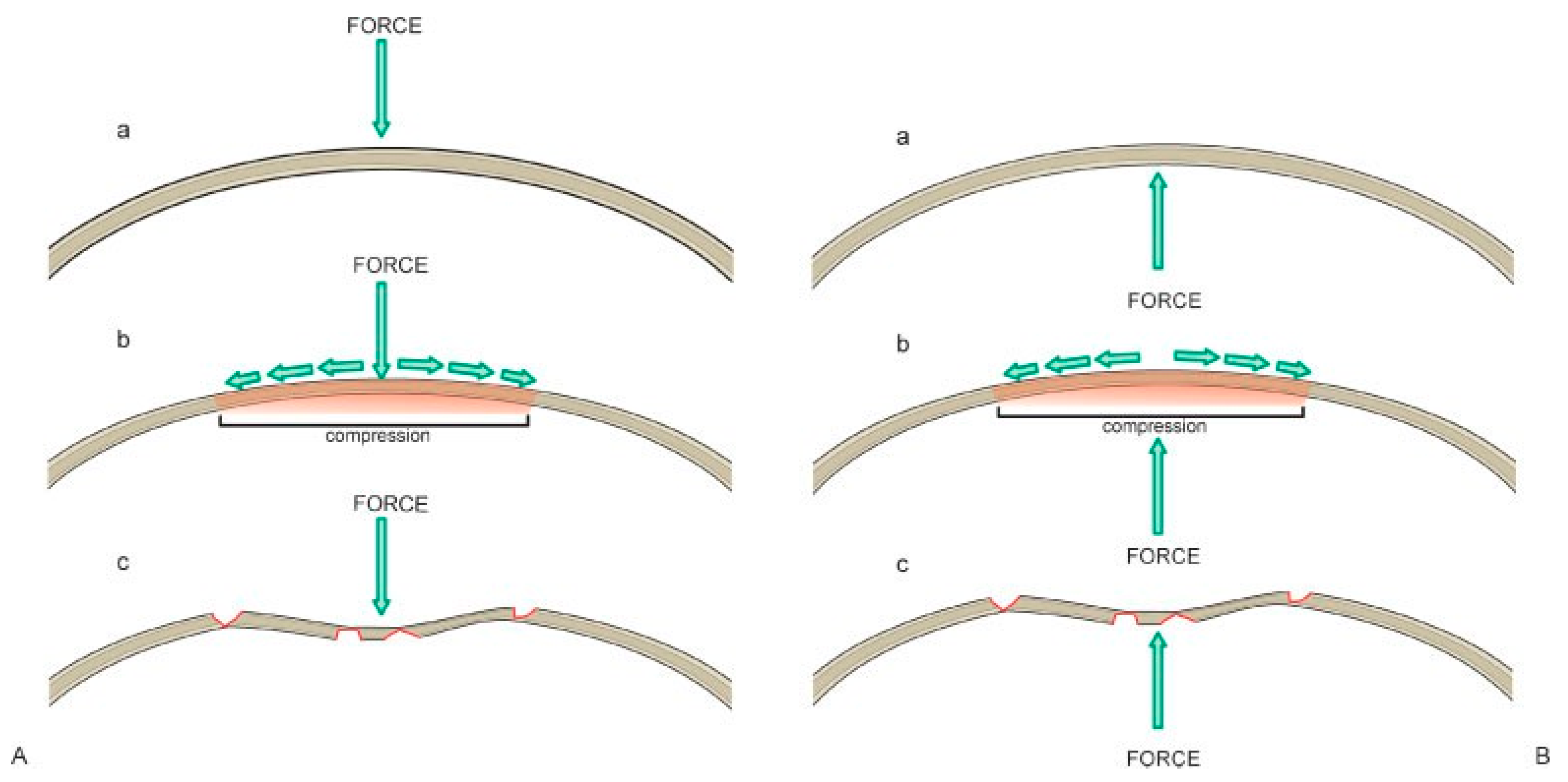

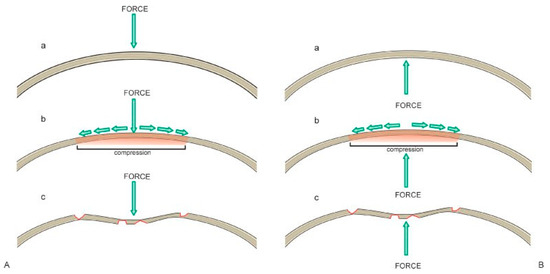

After complete exposure of the frontal bone, attention should be turned to fracture reduction. Reduc- tion of noncomminuted, compressed fractures can be extremely challenging. When the convex surface of the frontal bone is fractured, it goes through a compression phase before it becomes concave (Figure 17A). Fracture reduction requires enough force to pull the bone frag- ments back through the compression phase (Figure 17B). It may be necessary to remove a bone fragment, release the tension, and make room for reduction. If comminution exists or bone segments overlap at the fracture site, a small bone hook can be insinuated between the frag- ments to assist with elevation. Another technique is to place a 1.5- to 2.0-mm screw in the depressed segment, grasp the screw with a heavy hemostat, and pull upward to reduce the segment. Every attempt should be made to keep the majority of the fragments in place, as this will allow for a more accurate repair.

Figure 17.

(A) Illustration of the compressive forces on the frontal bone resulting from a frontal sinus fracture. (B) Illustration of the forces that must be applied to return the frontal bone to its premorbid convex shape.

Once the bone fragments are mobilized, the sinus mucosa should be evaluated. A 30-degree endoscope can be helpful to visualize the sinus and the nasofrontal recess through a limited bone defect. Mucosa involved in a fracture line should be removed to avoid entrapment. The fragments are then reduced and plated with 1.0 to 1.3 microplates. Small gaps (4 to 10 mm) can be reconstructed with titanium mesh. Hydroxyapatite bone cement should not be used to fill bone defects. It has an unacceptably high risk of infection and extrusion. However, bone pate, burred from intact calvarium, can be used in combination with a pericranial flap to smooth surface irregularities. During wound closure, it is important to resuspend the temporal soft tissues to avoid long-term ptosis of the forehead and upper midface. Two 2–0 monofilament sutures are passed through the temporoparietal fascia and suspended up to the tempo- ralis muscle fascia (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Intraoperative photo of a suture used to resuspend the scalp and midface during closure of the coronal incision.

Frontal Sinus Obliteration

More severe injuries may require frontal sinus obliter- ation. This involves exposure of the entire sinus, fastid- ious removal of all sinus mucosa, and obliteration of the cavity with autologous materials. Many different mate- rials have been used for sinus obliteration including abdominal fat, cancellous bone, muscle, pericranium, and spontaneous osteoneogenesis with ‘‘auto-oblitera- tion.’’[4,6] The author prefers abdominal fat.

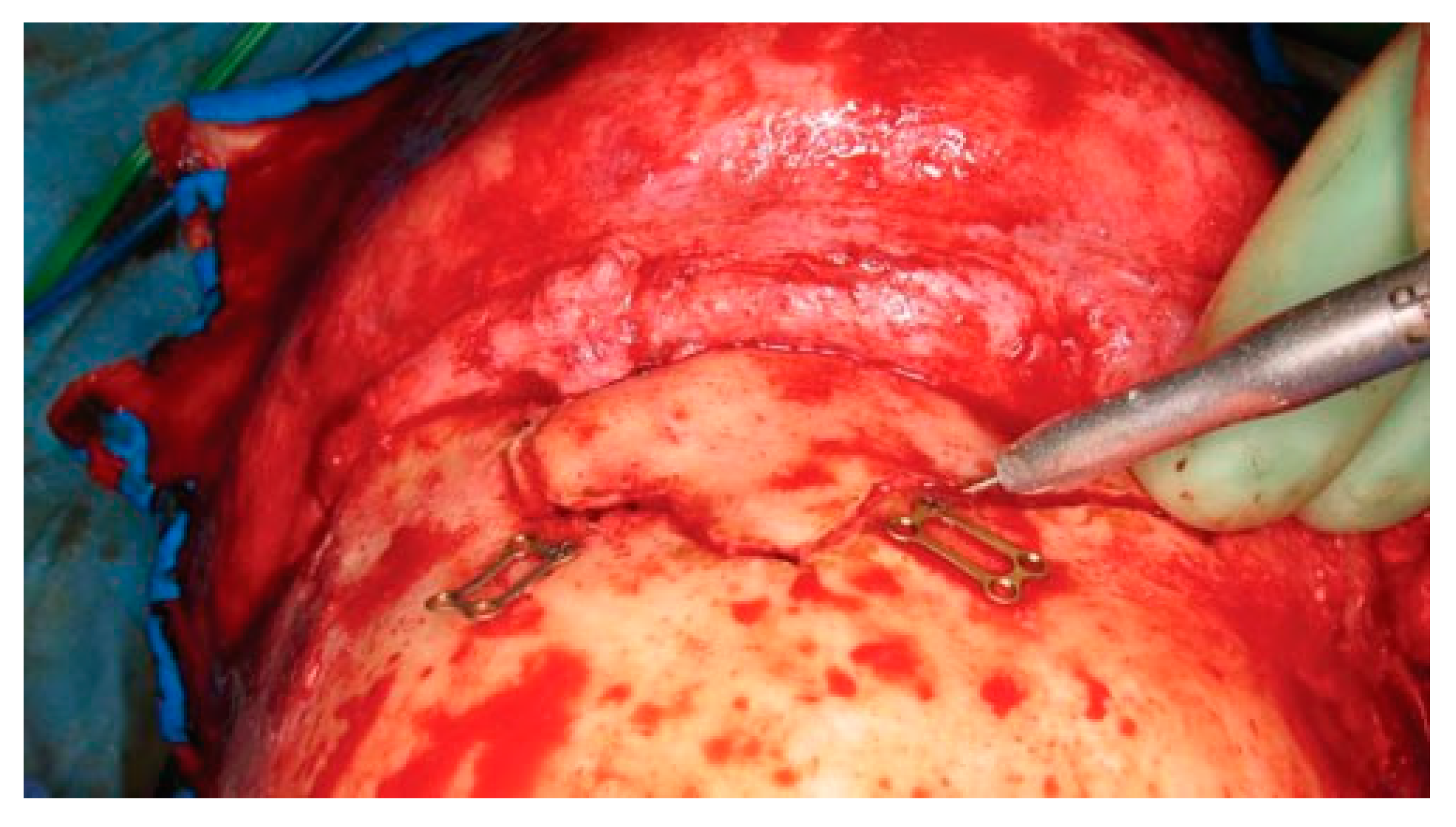

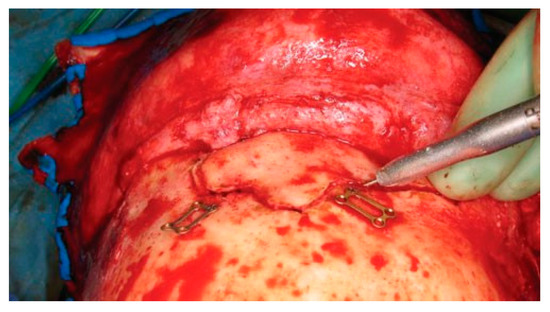

The patient gives consent after being informed of the risks of bleeding, infection, paresthesia, brain injury, CSF leak, meningitis, diplopia, visual loss, external deformity, and late mucocele formation. A coronal flap is used to expose the fracture as previously described. The full pericranial flap should be maintained to repair any CSF leak, dural defect, or obliteration of the sinus. After complete exposure, all anterior table bone frag- ments should be removed and kept moist. Placing the fragments atop a drawing of the fracture will help maintain the anatomic orientation of each segment prior to the repair. With fractures isolated to one side of the sinus, it is often necessary to perform a frontal sinus- otomy to remove the remainder of the anterior table bone. Localization of the sinusotomy cuts can be per- formed in several ways. Historically a ‘‘6-foot penny Caldwell’’ X-ray was used (i.e., anterior-posterior Cald- well X-ray with the patient placed 6 feet from the X-ray tube). However, current digital radiograph technology has made these images difficult to obtain. Intraoperative navigation is accurate but requires a specialized scan and navigation hardware. Alternatively, one tine of a bipolar cautery can be placed on each side of the anterior table. The internal tine is then used to ‘‘walk’’ around the periphery of the sinus, and the outer tine is used to mark an outline of the sinus using a bovie electrocautery (Figure 19). A final technique involves insertion of a light source into the sinus through a fracture line; this trans- illuminates the periphery of the sinus and guides the osteotomy.

Figure 19.

Intraoperative photo demonstrating the use of bayonet forceps to outline the periphery of the frontal sinus.

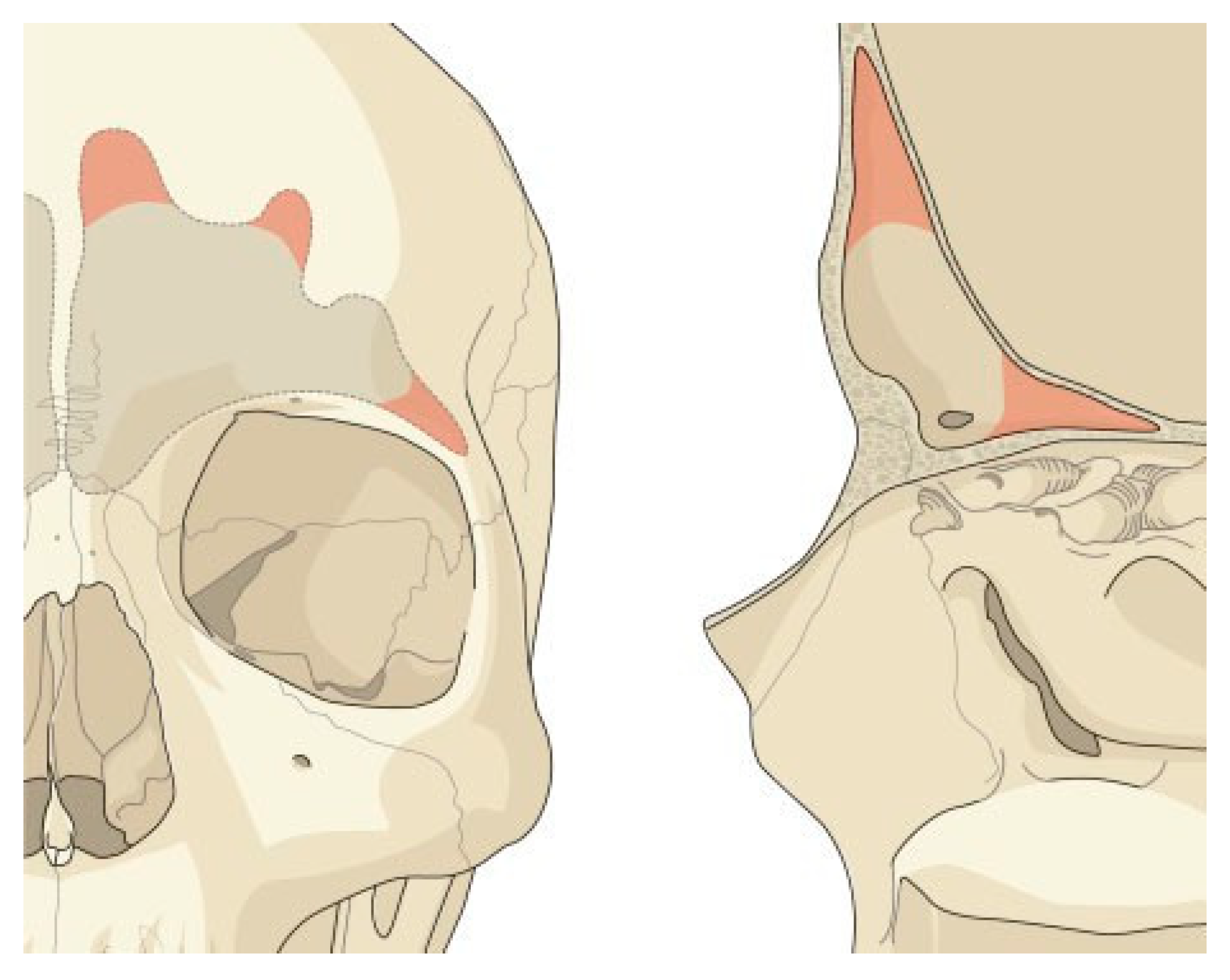

After the limits of the sinus have been defined, two microplates (1.0 to 1.3 mm) are preapplied with 3- to 4-mm screws, spanning the proposed osteotomy site. This allows the surgeon to accurately reapproximate the bone fragments despite the fact that a bone defect (or kerf) will be formed with the osteotomy. Although a sagittal saw can be used to perform the sinusotomy, the author prefers a Midas Rex drill (Medtronic, Fort Worth, TX) with a B-1 bit, which has both drilling and side-cutting capabilities. The surgeon should ini- tially use the bit to drill ‘‘postage stamp’’ perforations around the periphery of the sinus. The drill must be angled toward the sinus cavity to avoid intracranial penetration and injury. The side-cutting capability of the bit can then be used to join the perforations and complete the osteotomy (Figure 20). Care should be taken to avoid obliteration of the predrilled miniplate holes while performing the osteotomy. Particular attention should be paid to osteotomize the lateral orbital rims and the glabella without injury to the supraorbital/supratrochlear neurovascular pedicles. These osteoto- mies can be performed with a sharp 2- to 4-mm osteotome or the B-1 bit. A curved 4-mm osteotome is then inserted along the frontal osteotomy and used to break down any intersinus septations. Finally the ante- rior table is outfractured and hinged anteriorly.

Figure 20.

Intraoperative photo of a frontal sinusotomy. The drill should be held at an angle to avoid entry into the intracranial cavity. Note that the plates used for fixation of the anterior table bone at the end of the procedure have been preapplied prior to the sinusotomy.

After complete exposure of the sinus, the pos- terior table integrity is evaluated. If it is stable and free of large defects, sinus obliteration is acceptable. How- ever, all sinus mucosa must be meticulously removed from both the posterior and anterior (i.e., fracture fragments) tables. The author prefers to start with a large (4- to 6-mm) cutting burr and move to small diamond burrs for deeper in the sinus. Access to the deepest portions of the sinus can be extremely chal- lenging in patients with pronounced pneumatization. Special attention must be paid to the scalloped areas deep in the sinus (Figure 21). If the orbital roof has significant convexity, it may be necessary to remove a portion of the roof to gain access the posterior sinus mucosa. After complete removal of the sinus mucosa, attention is turned to the frontal recess. The mucosa of the frontal sinus infundibulum is elevated and inverted into the frontal recess. A small temporalis muscle plug is then placed into the frontal recess to obliterate the ostia. Finally, a sharp 5-mm osteotome is used to obtain two 5 × 5-mm bone chips from the calvarium (Figure 22). These are inserted to block the frontal sinus infundibulum (Figure 23).

Figure 21.

Illustration highlighting the most difficult areas to completely remove the frontal sinus mucosa. Special attention must be given to these areas to avoid leaving remnants of sinus mucosa that will result in postoperative mucocele formation.

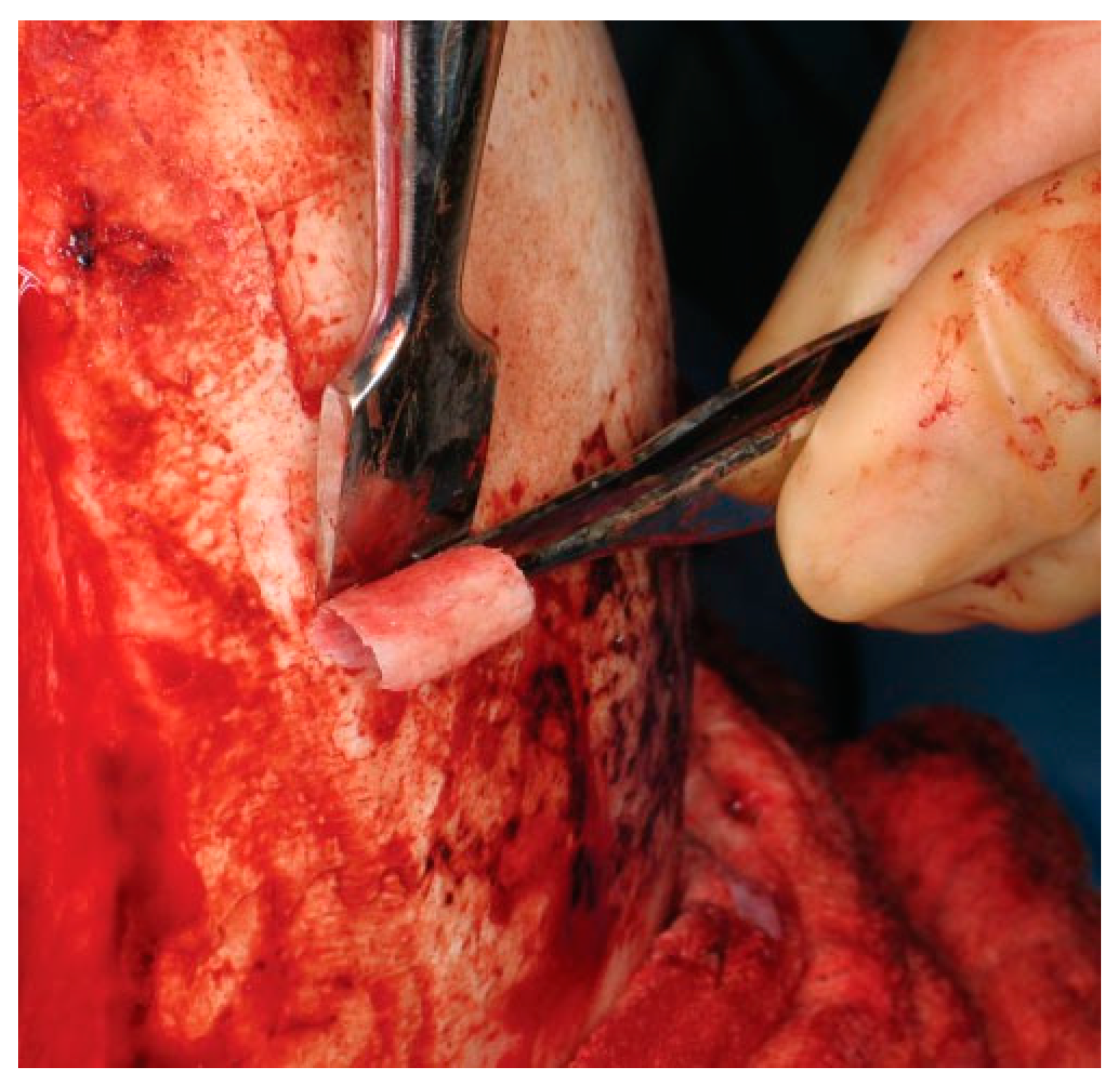

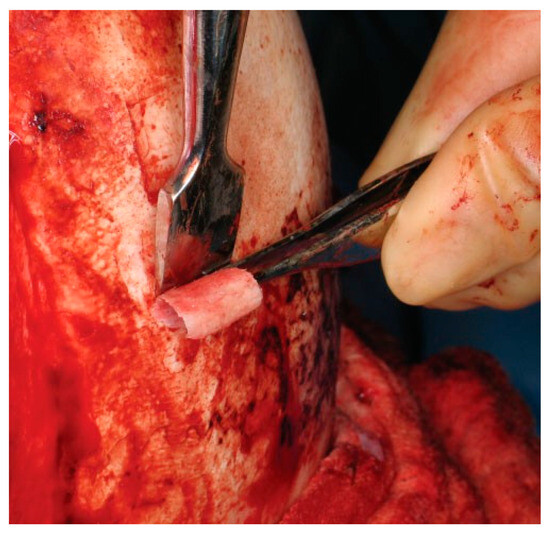

Figure 22.

Intraoperative photo of an outer table bone graft being harvested. The bone graft is then trimmed and positioned in the frontal recess to ensure separation of the nose and sinus.

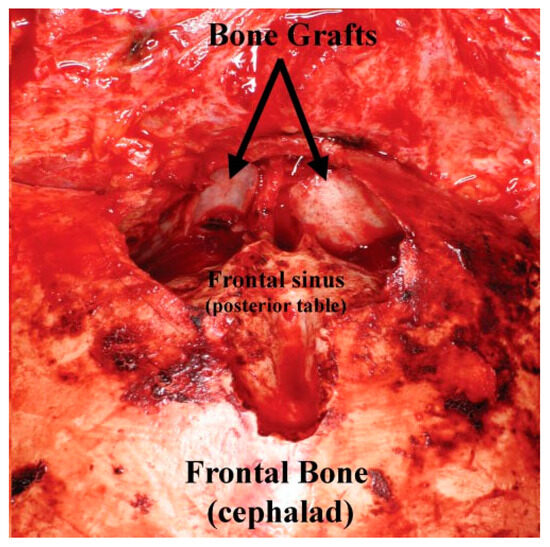

Figure 23.

Intraoperative photo of the bone graft (from Figure 22) placed into the frontal recess to obstruct the frontal recess outflow tract.

A fat graft is obtained through a left lower- quadrant (or periumbilical) incision using a separate, sterile instrument set. An attempt should be made to harvest the fat graft in a single piece, with minimal trauma and avoiding electrocautery when possible. The fat graft is then trimmed and inserted into the sinus cavity. The anterior table fragments are replaced. The fat should meet but not extrude into the saw kerf. Anterior table stabilization is achieved with 1.0- to 1.3-mm microplates, mesh, and/or bone paˆté as described under ‘‘Open Reduction and Internal Fixation’’.

Frontal Sinus Cranialization

The most severe injuries with disruption of the posterior table will require frontal sinus cranialization. Consulta- tion with a neurosurgical colleague is recommended. The surgical approach is identical to that described under ‘‘Frontal Sinus Obliteration’’; however, maintaining the integrity of the pericranial flap becomes more critical for dural repair and control of CSF leaks. All free bone fragments from the anterior and posterior table are removed. Larger pieces to be used for reconstruction should be drilled free of mucosa. Once the dura is exposed, any adherent posterior table bone fragments should be carefully dissected from the dura with Penfield elevators. The brain should be gently retracted and dura elevated from any remaining portion of the posterior table. The remaining posterior table bone is then re- moved using straight and angled (Kerrison) rongeurs. A drill should be used to smooth the posterior table edge flush with the anterior sinus walls, floor, and anterior cranial fossa. The frontal recess is occluded as previously described in ‘‘Frontal Sinus Obliteration.’’ Simple lacer- ations of the dura can be repaired with interrupted 5–0 nylon sutures. More complex injuries may require neuro- surgical debridement and closure with a pericranial flap. When a pericranial flap is used, a small bony defect must be fashioned just above the orbital rims. This allows the flap to pass intracranially without cutting off the blood supply. The anterior table is then reconstructed using 1.0 to 1.3 microplates and mesh. The bony dis- ruption may be so severe that posterior table fragments are required to reconstruct the anterior table. The in- cision is closed as described under ‘‘Open Reduction and Internal Fixation.’’

References

- Nahum, A.M. The biomechanics of maxillofacial trauma. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1975, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strong, E.B.; Sykes, J.M. Frontal sinus and nasoorbitoethmoid complex fractures. In Facial Plastic Recon- Structive Surgery, 2nd ed.; Papel, I.D., Ed.; Thieme Medical Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 747–758. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw-Wall, B. Frontal sinus fractures. Facial Plast. Surg. 1998, 14, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Hollier, L.H. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Changing concepts. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1992, 19, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, A.; Donald, P.J. Frontal sinus fractures: A review of 72 cases. Laryngoscope 1988, 98 Pt 1, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, E.D.; Stanwix, M.G.; Nam, A.J.; et al. Twenty-six-year experience treating frontal sinus fractures: A novel algorithm based on anatomical fracture pattern and failure of conven- tional techniques. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 122, 1850–1866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anon, J.B.; Rontal, M.; Zinreich, S.J.; et al. Anatomy of the Paranasal Sinuses; Thieme Medical Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Stammberger, H.R.; Kennedy, D.W. The Anatomic Terminology Group. Paranasal sinuses: Anatomic terminology and nomen- clature. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. Suppl. 1995, 167, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.L.; Han, J.K.; Loehrl, T.A.; Rhee, J.S. Endoscopic management of the frontal recess in frontal sinus fractures: A shift in the paradigm? Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strong, E.B.; Buchalter, G.M.; Moulthrop, T.H. Endoscopic repair of isolated anterior table frontal sinus fractures. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 2003, 5, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, H.D.I.I.I.; Spring, P. Endoscopic repair of frontal sinus fracture: Case report. J. Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 1996, 2, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lappert, P.W.; Lee, J.W. Treatment of an isolated outer table frontal sinus fracture using endoscopic reduction and fixation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 1642–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiger, J.D.; Alexander, G.C.; Francis, D.O.; Palmer, J.N. Endo- scopic-assisted reduction of anterior table frontal sinus fractures. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 1936–1939. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, E.B.; Kellman, R.M. Endoscopic repair of anterior table—Frontal sinus fractures. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 2006, 14, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.K.; Mueller, R.; Huang, F.; Strong, E.B. Endoscopic repair of anterior table: Frontal sinus fractures with a Medpor implant. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2007, 136, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, P.J. Frontal sinus ablation by cranialization. Report of 21 cases. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1982, 108, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cordier, B.C.; de la Torre, J.I.; Al-Hakeem, M.S.; et al. Endoscopic forehead lift: Review of technique, cases, and complications. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2002, 110, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2008 by the author. The Author(s) 2008.