Surgical Management of Isolated Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures: Role of Objective Morphometric Analysis in Decision-Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

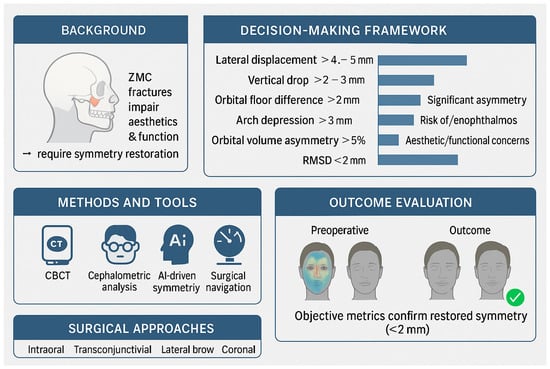

3.1. Surgical Approaches for Isolated ZMC Fractures

- Intraoral (Keen’s) approach: Incision inside the upper lip (buccal sulcus) to reach the zygomaticomaxillary buttress and lateral maxilla, providing a route to elevate and align the malar prominence from below with no external scar [11].

- Transconjunctival or subciliary approach: Incisions via the lower eyelid (inside the conjunctiva or just below the eyelashes) to access the infraorbital rim and orbital floor, often used when the orbital margin or floor requires repair; these approaches leave either no scar or a well-concealed scar [11,12].

- Lateral brow or upper eyelid approach: A small incision in the lateral eyebrow region or within the upper eyelid crease to expose the frontozygomatic suture (lateral orbital rim) for fracture reduction and plating; this approach avoids a visible scar on the forehead [13].

- Temporal (Gillies) approach: A short incision behind the hairline in the temple, allowing insertion of an instrument to lever and elevate a depressed zygomatic arch. This minimally invasive technique is effective for isolated arch displacement and is often adjunctive to other exposures [14].

- Coronal (hemicoronal) approach: A longer incision across the scalp behind the hairline for wide access to the zygoma, orbital rims, and arch. Reserved for comminuted or complex fractures, it provides excellent visualization at the cost of a more extensive dissection [15].

3.2. Conventional Imaging and Morphometric Assessment

3.3. Modern 3D Technologies and Quantitative Tools

3.4. Integration of Objective Metrics in Planning and Outcome Evaluation

3.5. Towards an Objective Decision-Making Framework

3.6. Current Limitations and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ZMC | Zygomaticomaxillary complex |

| ORIF | Open reduction and internal fixation |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CBCT | Cone-beam computed tomography |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| RMSD | Root mean square distance |

References

- Yamsani, B.; Gaddipati, R.; Vura, N.; Ramisetti, S.; Yamsani, R. Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures: A Review of 101 Cases. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2015, 15, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Anwar, M.W.; El-Anwar, M.W. Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fracture as an Orbital Wall Fracture. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, C.Y.; Barrera, J.E.; Kwon, J.; Most, S.P. Three-Dimensional Analysis of Zygomatic-Maxillary Complex Fracture Patterns. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2010, 3, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, S.S.; Chung, S.A.; Rudolph, M.; Hemal, K.; Brown, P.J.; Runyan, C.M. Automated 3D Analysis of Zygomaticomaxillary Fracture Rotation and Displacement. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddy, K.; Dierks, E.J.; Cheng, A.; Patel, A.; Amundson, M.; Bell, R.B. Management of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures Utilizing Intraoperative 3-Dimensional Imaging: The ZYGOMAS Protocol. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 79, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Parashar, A. Unfavourable Outcomes in Maxillofacial Injuries: How to Avoid and Manage. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2013, 46, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Tak, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.-H. Reduction Malarplasty Using a Simulated Surgical Guide for Asymmetric/Prominent Zygoma. Head Face Med. 2022, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschl, L.M.; Wittmann, M.; von Bomhard, A.; Koerdt, S.; Unterhuber, T.; Kehl, V.; Deppe, H.; Wolff, K.; Mücke, T.; Fichter, A.M. Results of a Clinical Scoring System Regarding Symptoms and Surgical Treatment of Isolated Unilateral Zygomatico-Orbital Fractures: A Single-Centre Retrospective Analysis of 461 Cases. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiland, M.; Schulze, D.; Rother, U.; Schmelzle, R. Postoperative Imaging of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures Using Digital Volume Tomography. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committeri, U.; Arena, A.; Carraturo, E.; Austoni, M.; Germano, C.; Salzano, G.; De Riu, G.; Giovacchini, F.; Maglitto, F.; Abbate, V.; et al. Incidence of Orbital Side Effects in Zygomaticomaxillary Complex and Isolated Orbital Walls Fractures: A Retrospective Study in South Italy and a Brief Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikara, M.; Vakharia, K.T.; Greywoode, J. Zygomaticomaxillary Complex–Orbit Fracture Alignment. JAMA Facial Plast. Surg. 2018, 20, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosh, B.; Giraddi, G. Transconjunctival Preseptal Approach for Orbital Floor and Infraorbital Rim Fracture. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2011, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panneerselvam, E.; Pandya, A.; Vignesh, N.A.; Krishnakumar, V.R. Evaluation of Sub-Brow Approach to the Frontozygomatic Suture for Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF) of Zygomatico Maxillary Complex (ZMC) Fractures: A Prospective Cohort Study. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melek, L.; Noureldin, M. Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures: Finding the Least Complicated Surgical Approach (A Randomized Clinical Trial). BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, S.K.; Saikrishna, D.; Kumaran, S. A Study on Coronal Incision for Treating Zygomatic Complex Fractures. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2009, 8, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.M.; Kim, Y.B.; Shin, H.S.; Park, E.S. Orbital Floor Reconstruction Considering Orbital Floor Slope. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2011, 22, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.E.; Besmens, I.S.; Luo, Y.; Giovanoli, P.; Lindenblatt, N. Surgical Management of Isolated Orbital Floor and Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures with Focus on Surgical Approaches and Complications. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2020, 54, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starch-Jensen, T.; Linnebjerg, L.B.; Jensen, J.D. Treatment of Zygomatic Complex Fractures with Surgical or Nonsurgical Intervention: A Retrospective Study. Open Dent. J. 2018, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cewe, P.; Vorbau, R.; Omar, A.; Elmi-Terander, A.; Edström, E. Radiation Distribution in a Hybrid Operating Room, Utilizing Different X-Ray Imaging Systems: Investigations to Minimize Occupational Exposure. J. NeuroInterv. Surg. 2021, 14, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, F.; Kohl, K.; Privalov, M.; Franke, J.; Vetter, S.Y. Intraoperative 3D Imaging with Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Leads to Revision of Pedicle Screws in Dorsal Instrumentation: A Retrospective Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmani, N.; Hashmani, S. Understanding Ocular Visual Function Beyond the Sphere and Cylinder Using Multimodal Imaging. Pak. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 37, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häner, S.T.; Kanavakis, G.; Matthey, F.; Gkantidis, N. Valid 3D Surface Superimposition References to Assess Facial Changes during Growth. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.D.; Singh, M. Virtual Surgical Planning: Modeling from the Present to the Future. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutbi, M. Artificial Intelligence-Based Applications for Bone Fracture Detection Using Medical Images: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, A.; Hofmann, E.; Steinberg, A.; Lauer, G.; Kitzler, H.H.; Leonhardt, H. Probing Real-World Central European Population Midfacial Skeleton Symmetry for Maxillofacial Surgery. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosterhoff, J.H.F.; Doornberg, J.N. Artificial Intelligence in Orthopaedics: False Hope or Not? A Narrative Review along the Line of Gartner’s Hype Cycle. EFORT Open Rev. 2020, 5, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, B.; Osswald, C.R.; Rabon, M.; Sandoval-Garcia, C.; Guillaume, D.; Wong, X.; Venteicher, A.S.; Darrow, D.; Park, M.C.; McGovern, R.A.; et al. Learning Curve Associated with ClearPoint Neuronavigation System: A Case Series. World Neurosurg. X 2021, 13, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, M.; Panwar, S. Role of Navigation in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: A Surgeon’s Perspectives. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2021, 2021, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabelis, J.F.; Schreurs, R.; Essig, H.; Becking, A.G.; Dubois, L. Personalized Medicine Workflow in Post-Traumatic Orbital Reconstruction. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, L.R.; Júnior, E.Á.G.; Magro-Érnica, N.; Griza, G.L.; Conci, R.A.; Nadal, L. The Role of Computed Tomography in Zygomatic Bone Fracture—A Case Report. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 10, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, R.; Dubois, L.; Becking, A.G.; Maal, T. Quantitative Assessment of Orbital Implant Position—A Proof of Concept. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ching, S.; Thoma, A.; McCabe, R.E.; Antony, M.M. Measuring Outcomes in Aesthetic Surgery: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2003, 111, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Harner, C.D.; Zhang, X. The Morphometry of Soft Tissue Insertions on the Tibial Plateau: Data Acquisition and Statistical Shape Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passias, P.G.; Williamson, T.K.; Mir, J.; Smith, J.S.; Lafage, V.; Lafage, R.; Line, B.; Daniels, A.H.; Gum, J.L.; Schoenfeld, A.J.; et al. Are We Focused on the Wrong Early Postoperative Quality Metrics? Optimal Realignment Outweighs Perioperative Risk in Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cho, J.; Shim, W.; Kim, S.-B. Retrospective Study about the Postoperative Stability of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fracture. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 43, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, S.; Nayak, S.; Chithra, A.; Roy, S. Outcomes of Non-Surgical Management of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2023, 22, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, F.J.; Deshpande, R. Evaluation of Machine-Generated Biomedical Images via A Tally-Based Similarity Measure. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melazzini, L.; Bortolotto, C.; Brizzi, L.; Achilli, M.F.; Basla, N.; Meo, A.D.; Gerbasi, A.; Bottinelli, O.M.; Bellazzi, R.; Preda, L. AI for Image Quality and Patient Safety in CT and MRI. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2025, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Lee, M.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, K.; Kim, T.J. Artificial Intelligence-Powered Quality Assurance: Transforming Diagnostics, Surgery, and Patient Care-Innovations, Limitations, and Future Directions. Life 2025, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, C.; Kanber, B.; Arthurs, O.J.; Shelmerdine, S.C. Commercially Available Artificial Intelligence Tools for Fracture Detection: The Evidence. BJR Open 2023, 6, tzad005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Begtary, S.S.; Gurabi, A.; Hegedus, P.; Marton, N. Advancements and Initial Experiences in AI-Assisted X-Ray Based Fracture Diagnosis: A Narrative Review. Imaging 2025, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|

| Lateral displacement (mm) | >4–5 mm displacement often requires surgical correction |

| Vertical displacement (mm) | >2–3 mm vertical drop associated with noticeable asymmetry |

| Orbital floor height difference (mm) | >2 mm difference risks diplopia or enophthalmos |

| Zygomatic arch depression (mm) | Impairs mandibular motion (trismus); >3 mm usually treated |

| Orbital volume asymmetry (%) | >5% asymmetry linked to cosmetic and functional issues |

| Root mean square distance (RMSD, mm) | Quantifies global facial asymmetry; <2 mm difference considered acceptable |

| Tool/Technique | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| CT (Computed Tomography) | Gold standard; detailed visualization of fractures; widely available | Radiation exposure; cost; requires expertise |

| CBCT (Cone-beam CT) | Lower radiation dose; high spatial resolution for facial skeleton | Limited soft tissue resolution; smaller field of view |

| Cephalometric Analysis | Simple linear/angular measurements; cost-effective | Two-dimensional; limited accuracy in complex 3D displacements |

| Intraoperative Imaging | Immediate confirmation of reduction; prevents revision surgery | Additional equipment and cost; increases OR time |

| 3D Photogrammetry | Non-invasive; radiation-free; serial follow-up possible | Requires specialized equipment; cost |

| Stereophotogrammetry | High accuracy 3D surface capture; reproducible symmetry analysis | Limited availability; requires standardization |

| AI-based Symmetry Analysis | Automated, objective, detects subtle asymmetry; predictive planning | Still under development; validation needed |

| Surgical Navigation | Real-time intraoperative guidance; increased precision in reduction | Expensive; steep learning curve; limited to specialized centers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the AO Foundation. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mijatov, S.; Mijatov, I.; Brajković, D.; Rodić, D.; Golubović, J. Surgical Management of Isolated Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures: Role of Objective Morphometric Analysis in Decision-Making. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2025, 18, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18040050

Mijatov S, Mijatov I, Brajković D, Rodić D, Golubović J. Surgical Management of Isolated Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures: Role of Objective Morphometric Analysis in Decision-Making. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2025; 18(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleMijatov, Saša, Ivana Mijatov, Denis Brajković, Dušan Rodić, and Jagoš Golubović. 2025. "Surgical Management of Isolated Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures: Role of Objective Morphometric Analysis in Decision-Making" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 18, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18040050

APA StyleMijatov, S., Mijatov, I., Brajković, D., Rodić, D., & Golubović, J. (2025). Surgical Management of Isolated Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures: Role of Objective Morphometric Analysis in Decision-Making. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 18(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18040050