Is Using the Harmonic Scalpel Better than Conventional Hemostasis in Neck Dissection? A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

Introduction

Methods

Search Strategy

Study Selection

Inclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criterion

Outcomes of Interest

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Statistical Analysis

Results

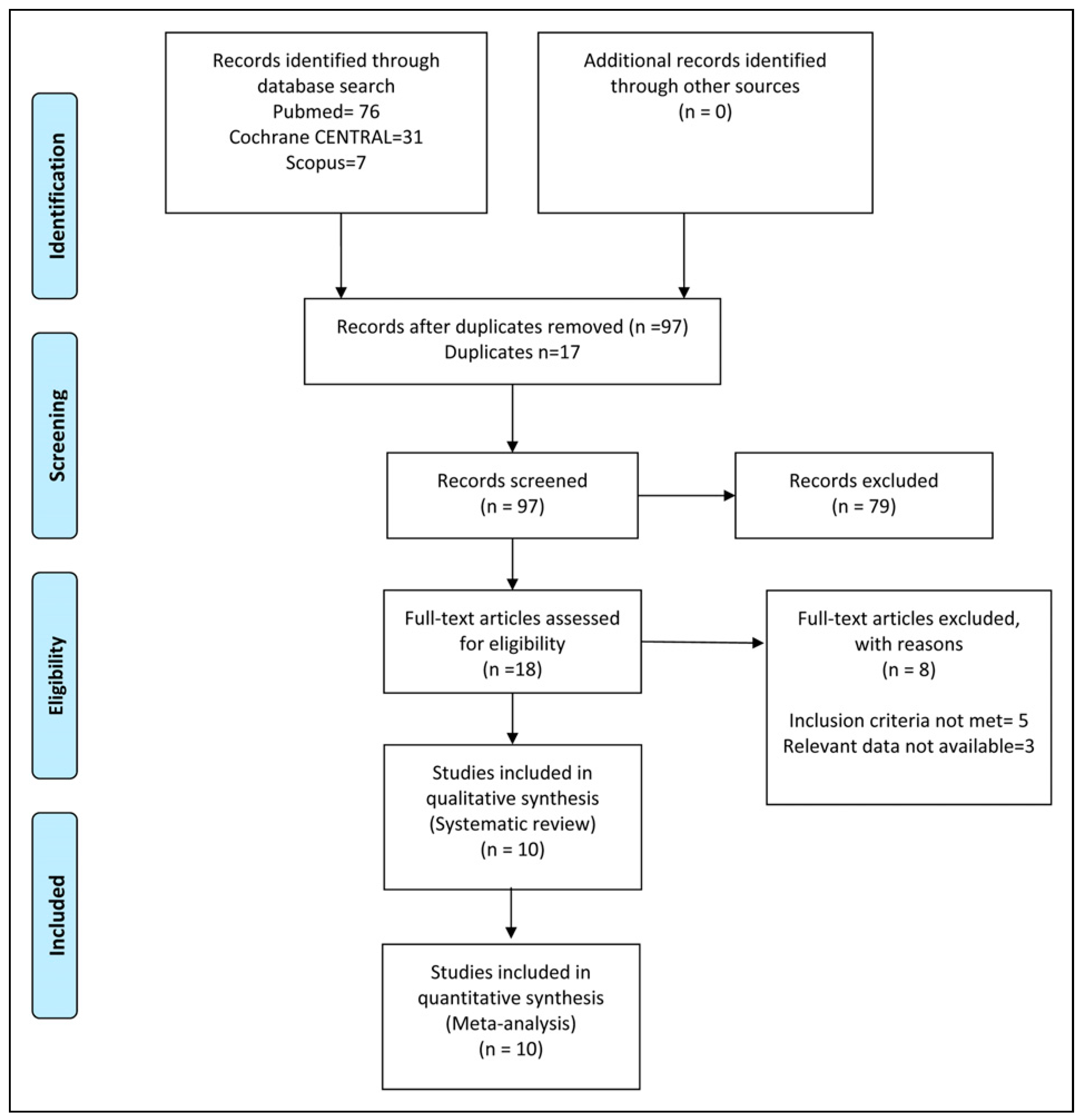

Literature Search Results

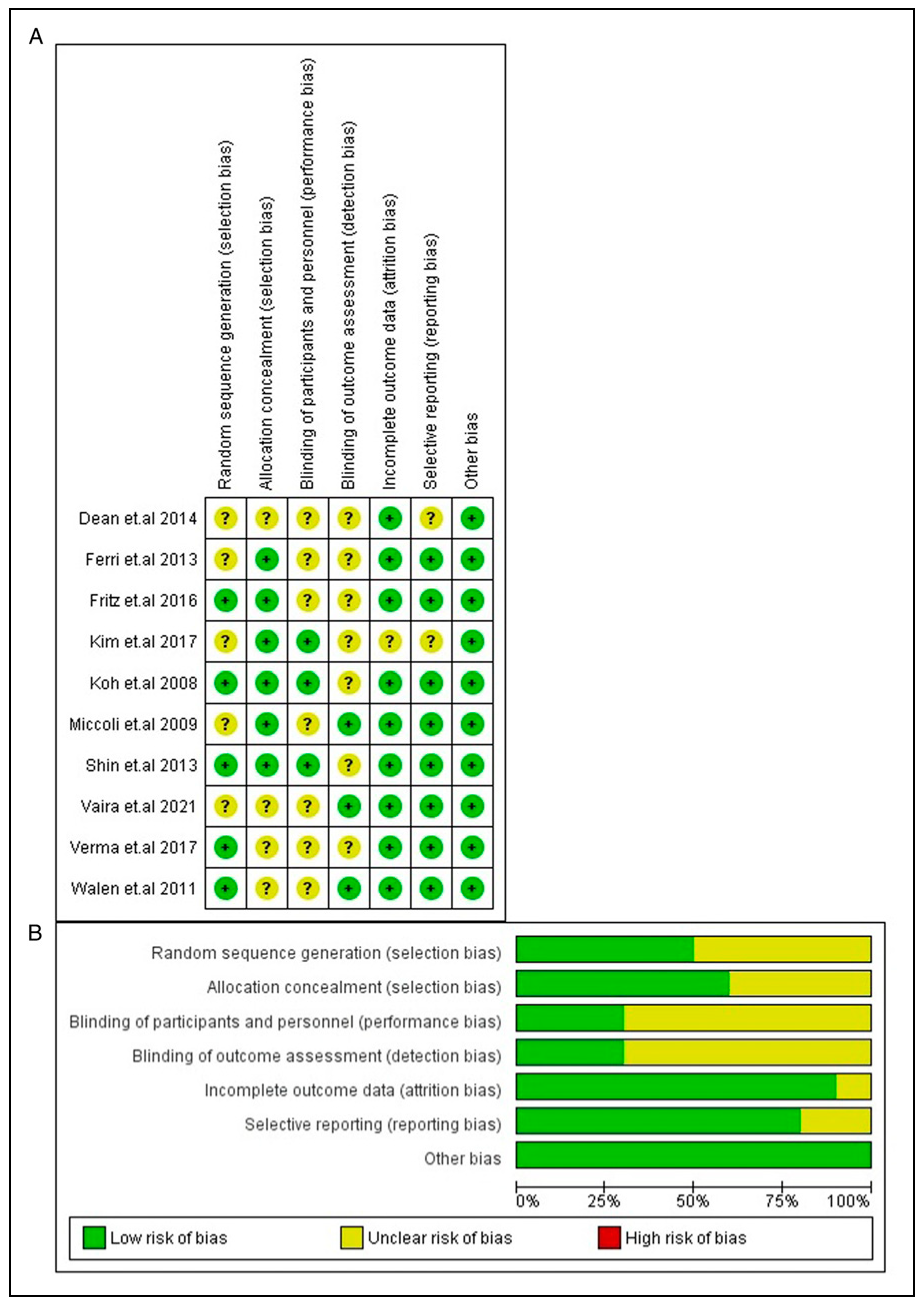

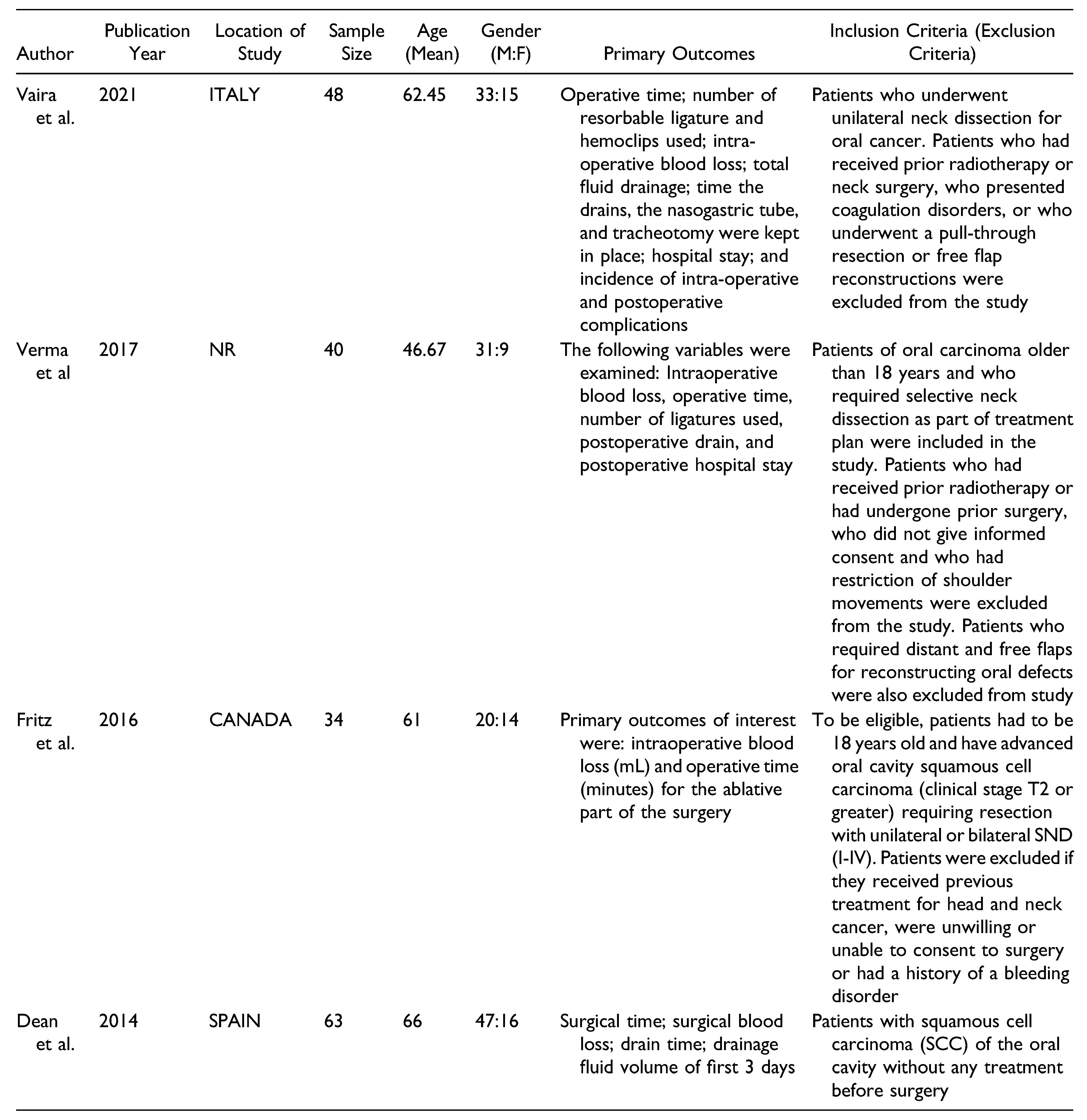

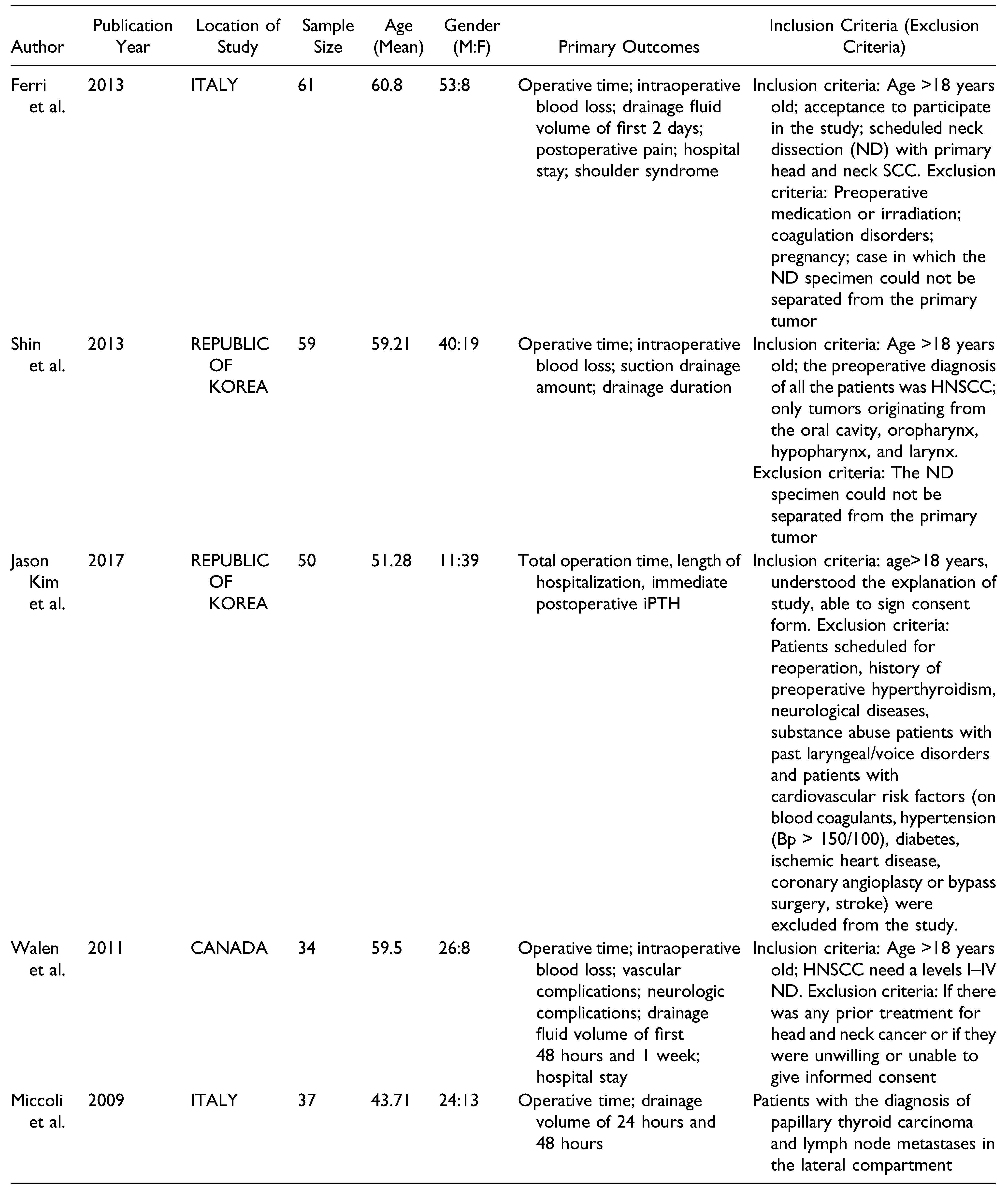

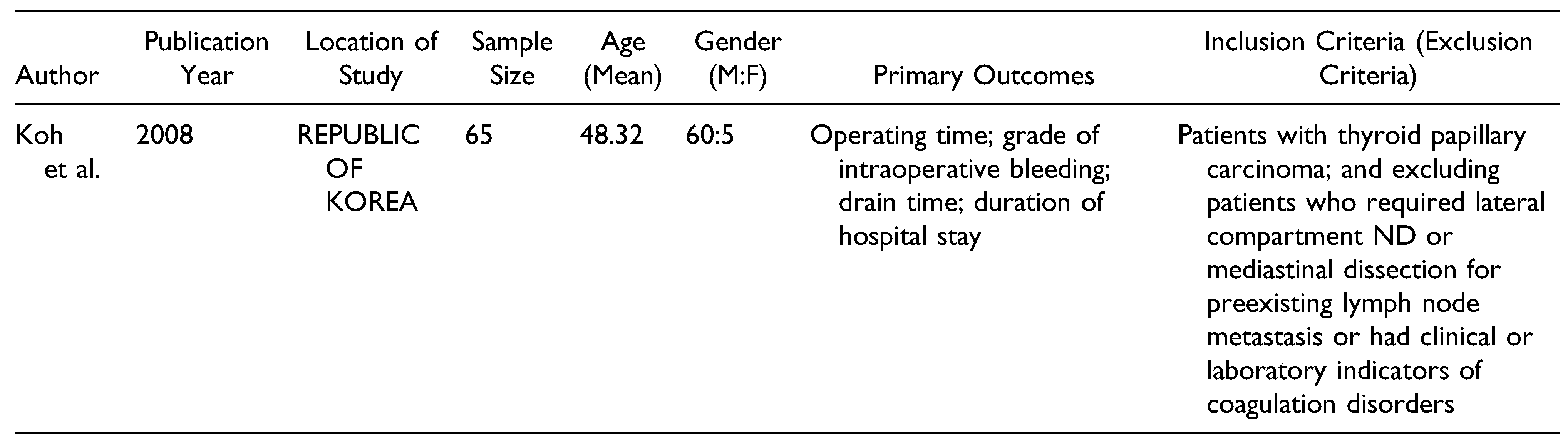

Study Characteristics and Quality Assessment

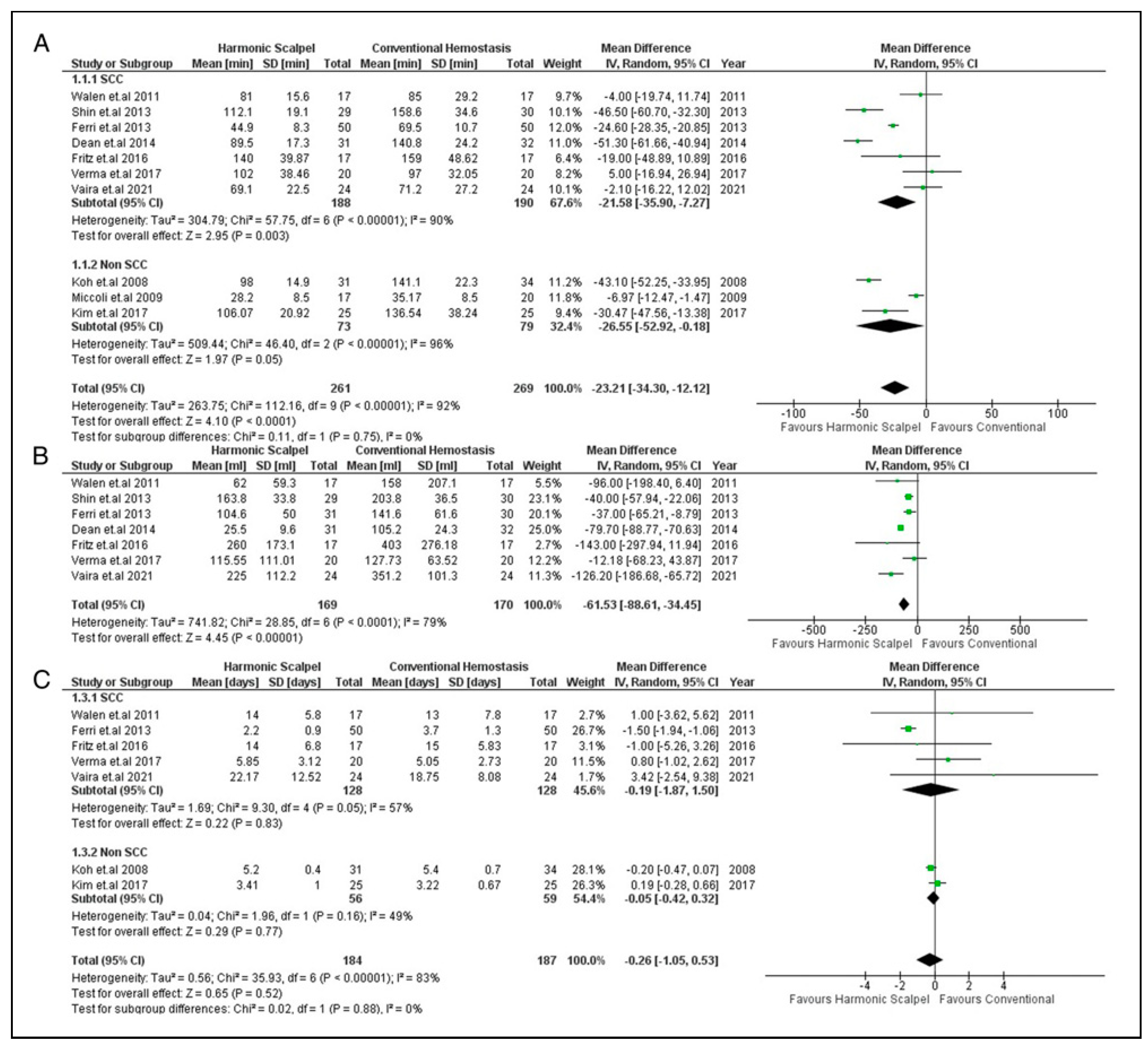

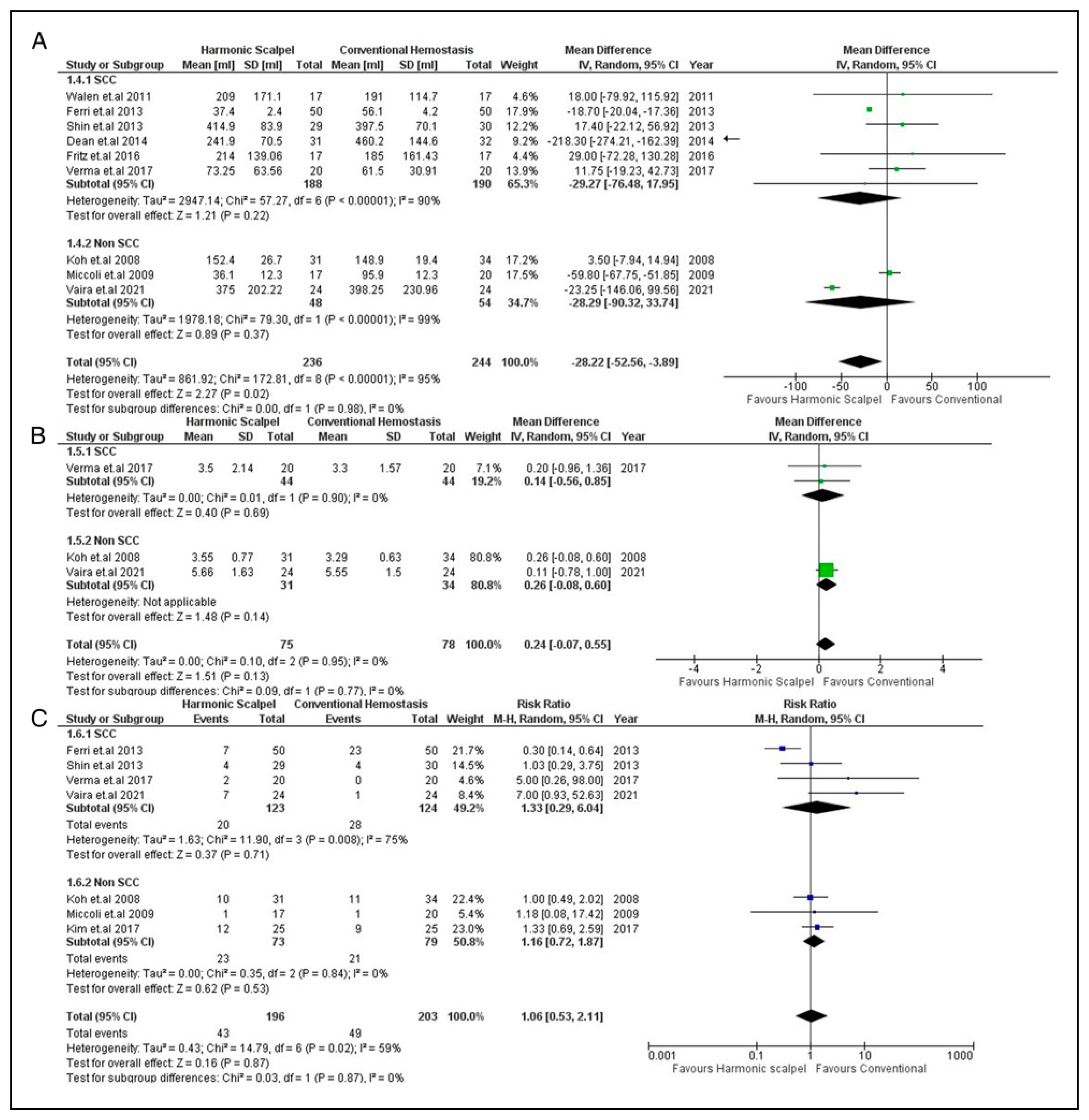

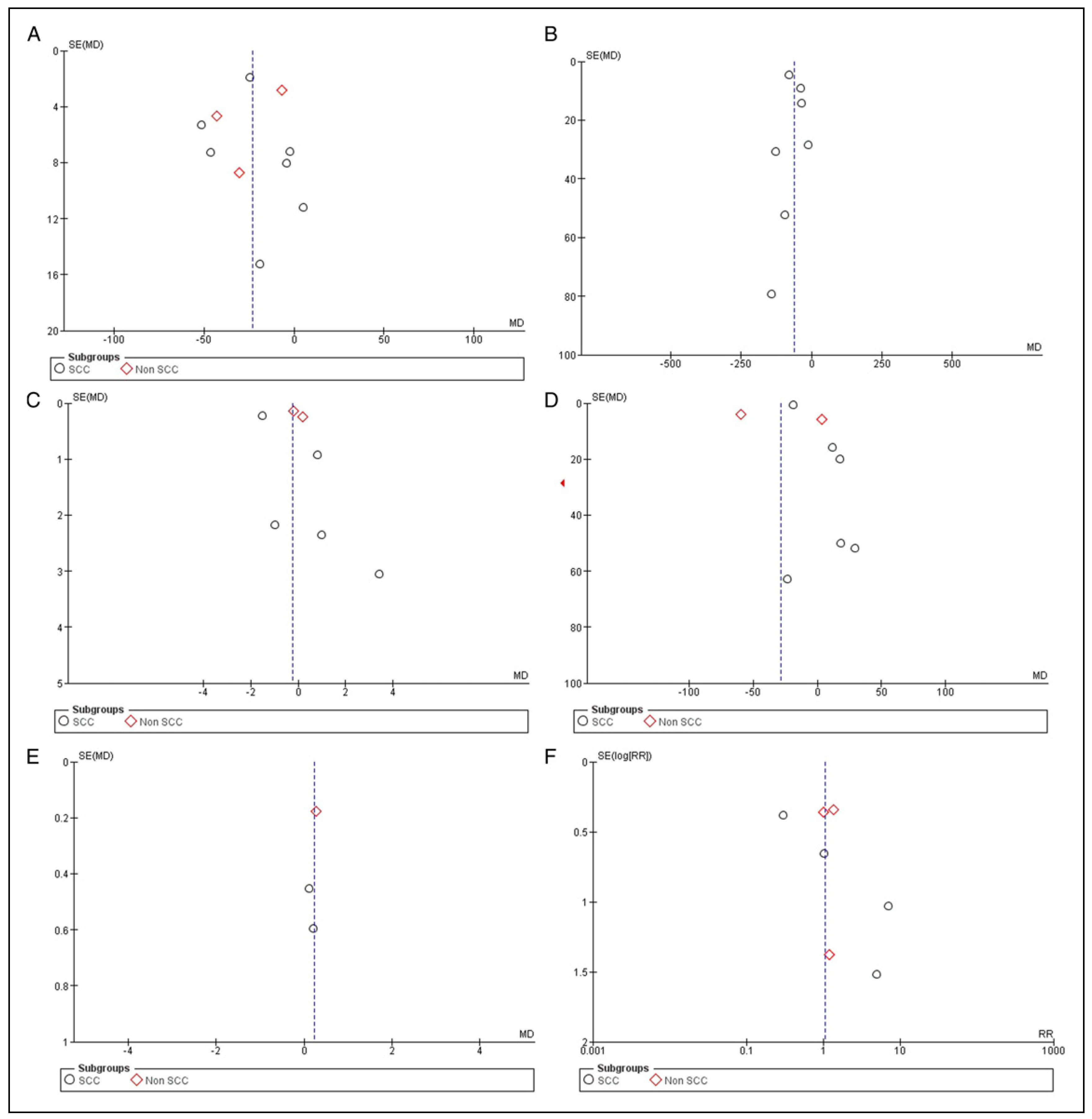

Primary Outcomes

Secondary Outcomes

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

Funding

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

IRB Approval

References

- Guo, K.; Xiao, W.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chen, G. Epidemiological Trends of head and neck cancer: a population-based study. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1738932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71(3), 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.uicc.org/news/globocan-2020-new-global-cancer-data.

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2020, 6(1), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, L.P.; Sanabria, A. Elective neck dissection in oral carcinoma: a critical review of the evidence. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2007, 27(3), 113–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salami, A.; Dellepiane, M.; Bavazzano, M.; Crippa, B.; Mora, F.; Mora, R. New trends in head and neck surgery: a prospective evaluation of the harmonic scalpel. Med. Sci. Mon. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2008, 14(5), 1–5. Available online: https://medscimonit.com/abstract/index/idArt/855735 (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Verma, R.K.; Mathiazhagan, A.; Panda, N.K. Neck dissection with harmonic scalpel and electrocautery? A randomised study. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2017, 44(5), 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.H.; Xu, J.L.; Fan, T.F.; Ji, T.; Wu, H.J.; Zhang, C.P. The harmonic scalpel versus conventional hemostasis for neck dissection: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2015, 10(7), e0132476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaira, L.A.; De Riu, G.; Ligas, E.; et al. Neck dissection with harmonic instruments and electrocautery: a prospective comparative study. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 25(1), 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, H.Y. Total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection using harmonic focus: a randomized clinical trial. Koren J. Endocr. Surg. 2017, 17(1), 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, D.K.; Matthews, T.W.; Chandarana, S.P.; Nakoneshny, S.C.; Dort, J.C. Harmonic scalpel impact on blood loss and operating time in major head and neck surgery: a randomized clinical trial. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2016, 45(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.W.; Park, J.H.; Lee, S.W.; Choi, E.C. The harmonic scalpel technique without supplementary ligation in total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection: a prospective randomized study. Ann. Surg. 2008, 247(6), 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miccoli, P.; Materazzi, G.; Fregoli, L.; Panicucci, E.; Kunz-Martinez, W.; Berti, P. Modified lateral neck lymphadenectomy: prospective randomized study comparing harmonic scalpel with clamp-and-tie technique. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2009, 140(1), 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.S.; Koh, Y.W.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, E.C. The efficacy of the harmonic scalpel in neck dissection: a prospective randomized study. Laryngoscope 2013, 123(4), 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, E.; Armato, E.; Spinato, G.; Lunghi, M.; Tirelli, G.; Spinato, R. Harmonic scalpel versus conventional haemostasis in neck dissection: a prospective randomized study. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 2013, 369345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walen, S.G.; Rudmik, L.R.; Dixon, E.; Matthews, T.W.; Nakoneshny, S.C.; Dort, J.C. The utility of the harmonic scalpel in selective neck dissection. A prospective, randomized trial. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2011, 144(6), 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, A.; Alamillos, F.; Centella, I.; Garc´ıa-A´ lvarez, S. Neck dissection with the harmonic scalpel in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. J. Cranio-Maxillo-Fac. Surg. 2014, 42(1), 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirelli, G.; Del Piero, G.C.; Perrino, F. Ultracision harmonic scalpel in oral and oropharyngeal cancer resection. J. Cranio-Maxillo-Fac. Surg. 2014, 42(5), 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haehl, E.; Ruhle, A.; David, H.; et al. Radiotherapy for geriatric head-and-neck cancer patients: what is the value of standard treatment in the elderly? Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, M.; Engelke, W. Advantages of a new technique of neck dissection using an ultrasonic scalpel. J. Cranio-Maxillo-Fac. Surg. 2007, 35(1), 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Khan, S.; Chawla, T.; Murtaza, G. Harmonic scalpel versus electrocautery dissection in modified radical mastectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21(3), 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, E.; Armato, E.; Spinato, G.; Spinato, R. Focus harmonic scalpel compared to conventional haemostasis in open total thyroidectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2011, 2011, 357195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faisal, M.; Fathy, H.; Shaban, H.; Abuelela, S.T.; Marie, A.; Khaled, I. A novel technique of harmonic tissue dissection reduces seroma formation after modified radical mastectomy compared to conventional electrocautery: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Patient Saf. Surg. 2018, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Emam, T.A.; Cuschieri, A. How safe is high-power ultrasonic dissection? Ann. Surg. 2003, 237(2), 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantis, T.; Kontos, M.; Arvelakis, A.; et al. Comparison of monopolar electrocoagulation, bipolar electrocoagulation, Ultracision, and Ligasure. Surg. Today. 2006, 36(10), 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adwani, A.; Ebbs, S.R. Ultracision reduces acute blood loss but not seroma formation after mastectomy and axillary dissection: a pilot study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006, 60(5), 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | String | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (((“ultrasonically” [All fields] OR “ultrasonicated” [All fields] OR “ultrasonication” [All fields] OR“ultrasonicator" [All fields] OR “ultrasonics” [MeSH terms] OR “ultrasonics” [All fields] OR “ultrasonic” [All fields]) AND (“scalpel” [All fields] OR “scalpels” [All fields])) OR ((“harmonic” [All fields] OR “harmonical” [All fields] OR “harmonically” [All fields] OR “harmonicity” [All fields] OR “harmonics” [All fields]) AND (“scalpel” [All fields] OR “scalpels” [All fields])) OR ((“harmonic” [All fields] OR “harmonical” [All fields] OR “harmonically” [All fields] OR “harmonicity” [All fields] OR “harmonics” [All fields]) AND (“wood des focus” [Journal] OR “focus” [Journal] OR “focus Ohio dent” [Journal] OR “focus madison” [Journal] OR “focus am psychiatr publ” [Journal] OR “focus” [All fields]))) AND (“neck dissection” [MeSH terms] OR (“neck” [All fields] AND “dissection” [All fields]) OR “neck dissection” [All fields] OR (“neck dissection” [MeSH terms] OR (“neck” [All fields] AND “dissection” [All fields]) OR “neck dissection” [All fields] OR (“radical” [All fields] AND “neck” [All fields] AND “dissection” [All fields]) OR “radical neck dissection” [All fields])) | 76 |

| Cochrane CENTRAL | (Ultrasonic scalpel OR harmonic scalpel OR harmonic FOCUS) AND (neck dissection OR radical neck dissection) | 31 |

| SCOPUS | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((ultrasonic scalpel OR harmonic scalpel OR harmonic FOCUS) AND (neck dissection OR radical neck dissection)) | 7 |

| Postoperative Complications | Harmonic Scalpel | CT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Hypoparathyroidism | 16 | 41.02 | 14 | 47.06 |

| Seroma | 8 | 20.51 | 10 | 29.41 |

| Salivary fistula | 5 | 12.82 | 1 | 2.94 |

| Infection | 4 | 10.26 | 4 | 14.70 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy | 2 | 7.69 | 3 | 17.65 |

| Lymphatic leak | 2 | 5.13 | 0 | 0 |

| Hematoma | 1 | 2.56 | 1 | 2.94 |

| Hypocalcemia | 1 | 2.56 | 1 | 2.94 |

| Total | 39 | 100 | 34 | 100 |

| Factors | Bias Begg (P-value) | Bias Egger (P-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Operating time | .531 | .408 |

| Blood loss | .881 | .767 |

| Length of hospital stay | .652 | .739 |

| Total drain output | .835 | .127 |

| Length of drain stay | .602 | .685 |

| Postop complications | .881 | .323 |

© 2023 by the author. The Author(s) 2023.

Share and Cite

Hameed, I.; Khan, M.O.; Samad, S.A.; Mahmood, S.; Siddiqui, O.M.; Hameed, I.; Nashit, M.; Iqbal, A.; Marsia, S.; Al Shetawi, A.H. Is Using the Harmonic Scalpel Better than Conventional Hemostasis in Neck Dissection? A Meta-Analysis. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, 74-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231170924

Hameed I, Khan MO, Samad SA, Mahmood S, Siddiqui OM, Hameed I, Nashit M, Iqbal A, Marsia S, Al Shetawi AH. Is Using the Harmonic Scalpel Better than Conventional Hemostasis in Neck Dissection? A Meta-Analysis. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2024; 17(1):74-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231170924

Chicago/Turabian StyleHameed, Ishaque, Mohammad Omer Khan, Syed Abdus Samad, Samar Mahmood, Omer Mustafa Siddiqui, Indallah Hameed, Muhammad Nashit, Ayman Iqbal, Shayan Marsia, and Al Haitham Al Shetawi. 2024. "Is Using the Harmonic Scalpel Better than Conventional Hemostasis in Neck Dissection? A Meta-Analysis" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 17, no. 1: 74-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231170924

APA StyleHameed, I., Khan, M. O., Samad, S. A., Mahmood, S., Siddiqui, O. M., Hameed, I., Nashit, M., Iqbal, A., Marsia, S., & Al Shetawi, A. H. (2024). Is Using the Harmonic Scalpel Better than Conventional Hemostasis in Neck Dissection? A Meta-Analysis. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 17(1), 74-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231170924