Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) has been used for the removal of pharyngeal and laryngeal cancers with the objective to improve functional and aesthetic outcomes without worsening survival.[

1,

2] With the exponential increase in incidence of human papilloma virus (HPV)–related oropharyngeal cancers,[

3] surgical management is getting more preference as these patients are diagnosed earlier and live longer, and the lateonset morbidity of radiotherapy-based treatment is more severe.[

4] In oropharyngeal salivary origin tumors, where surgery is the primary essential modality, this modality may be used for better access to the oropharynx, avoiding a lip split approach with mandibulotomy. We report one such case.

Case Report

A 31-year-old male working in a furniture polishing company, with no comorbidities or tobacco-related habits, presented with insidious onset of a painless swelling on the tongue for 1 month. He was seen in the otorhinolaryngology department at a local hospital and evaluated with an incision biopsy of the lesion, which was reported as adenoid cystic carcinoma. He was referred to our department for further management.

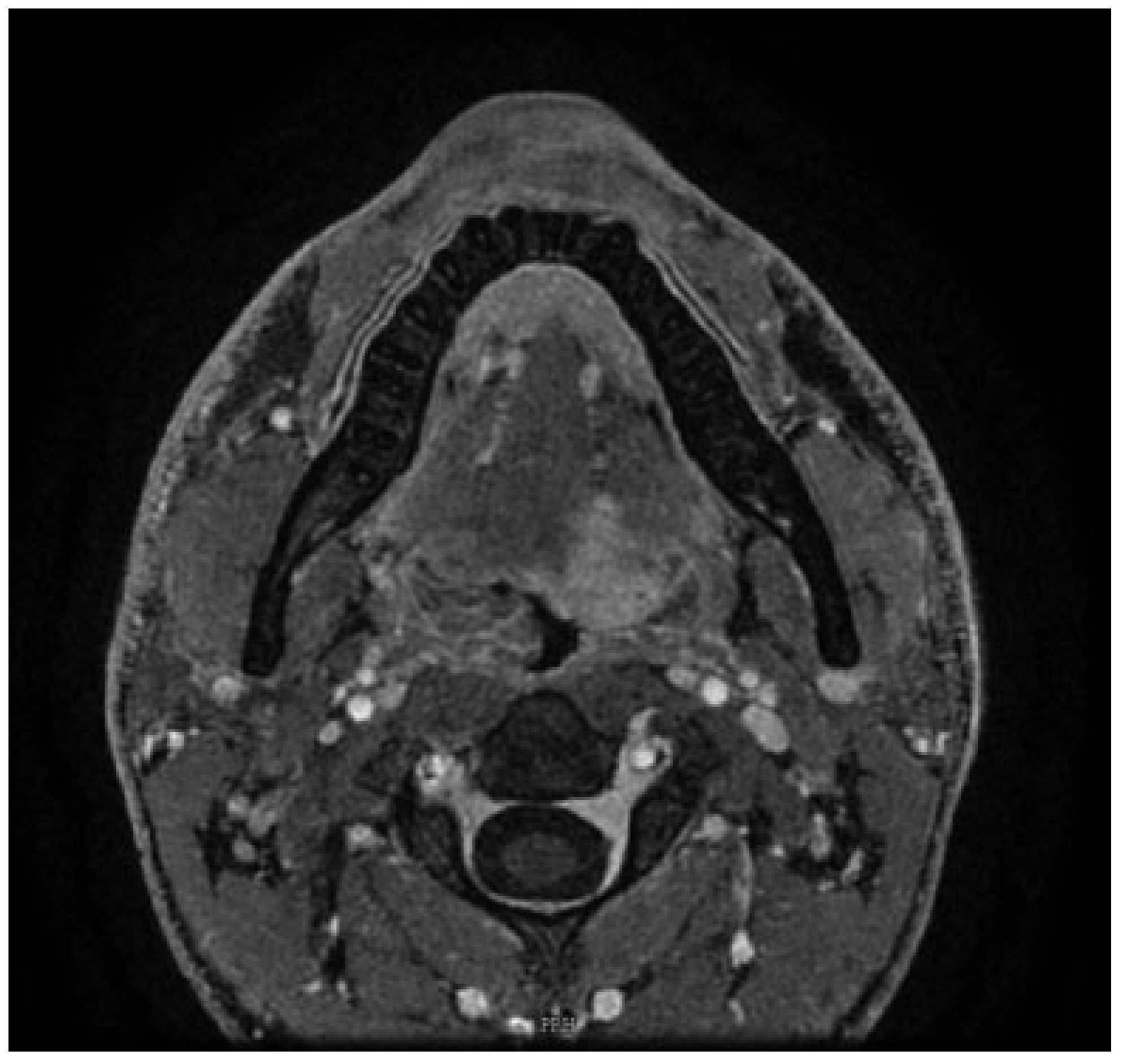

On clinical examination, the patient was fully dentate with an interincisor diameter of greater than 3.5 cm. On endoscopic examination, there was an exophytic growth arising from the left base of the tongue of size 3.5 × 2 cm, with a lateral extension to the left tonsillolingual sulcus. It extended medially toward the right base of tongue, not crossing midline in the oral tongue anteriorly and stopping short of vallecula posteriorly. The rest of pharynx and larynx appeared normal in structure and function. There were no palpable lymph nodes in the neck. Hence, it was staged as cT2N0M0 as per AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer; 7th Edition). A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck was performed, which revealed a 1.8 × 1.6 × 3.3 cm enhancing lesion involving the base of the tongue to the left of midline indenting on the left tonsil (

Figure 1). The lesion was seen extending till the midline of the tongue, involving the genioglossus and intrinsic muscles of the tongue. There was no significant cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no focal lung lesions on computed tomography (CT) of the chest. The patient’s case was discussed in the Head & Neck Multidisciplinary tumor board, and the patient was counseled for robotassisted surgery of left base of tongue with left level (I–III) neck dissection including selective arterial ligation, tracheostomy, and left radial forearm fasciocutaneous free flap.

Surgical Procedure

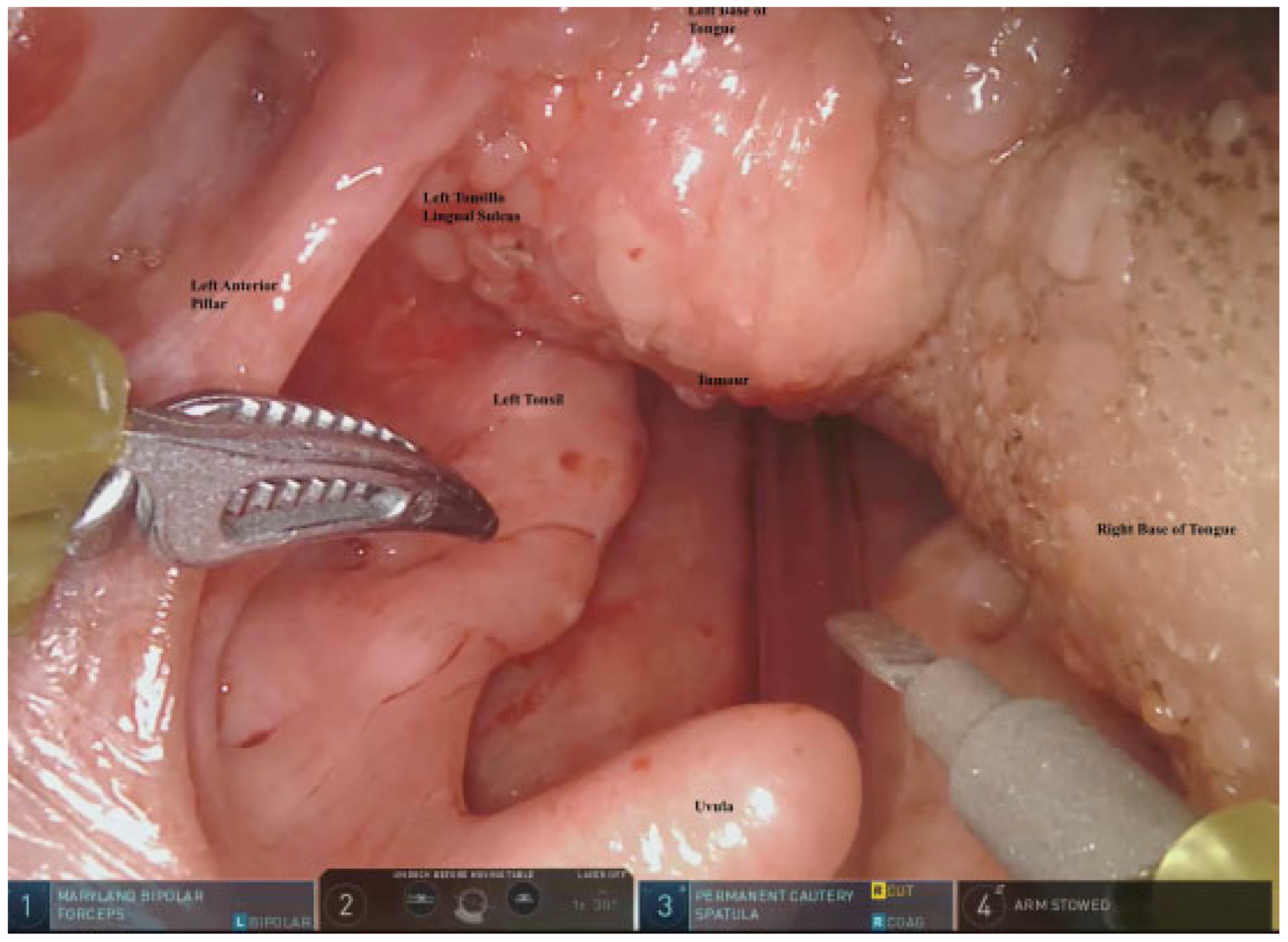

After endotracheal intubation, the patient underwent an elective tracheostomy. The procedure started with an ipsilateral selective neck dissection of levels I to III. Then the release of the suprahyoid musculature was done posteriorly, cutting the mylohyoid, hyoglossus, and posterior geniohyoid muscles. The carotid sheath and its contents were retracted laterally. Lingual and hypoglossal nerves were identified and preserved. The left lingual artery was ligated at its origin from the left external carotid artery. This technique of selective arterial ligation is performed to avoid postoperative hemorrhage from the bed of the tongue base resection. Attention was then diverted to the transoral robot-assisted part of the surgery. The mouth opening was stabilized with Boyle Davis mouth gag and tongue blade with Draffin bipod after insertion of a cheek retractor. A tongue stitch with silk was performed to keep the tongue protruded. Robotic docking into the mouth was done, with the robotic arms along with the 30-degree camera. A wide area around the tumor with a margin of 1 cm was mapped (

Figure 2). The excision of the tumor was performed with robotic instruments, monopolar cautery spatula, and Maryland bipolar forceps.

da Vinci Xi robot (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) was used. An upward facing camera, 8 mm, 30 degrees, was used for visualization. The excision crossed the midline, and the robotic cuts were connected to those made from the neck, resulting in a defect connected to the neck.

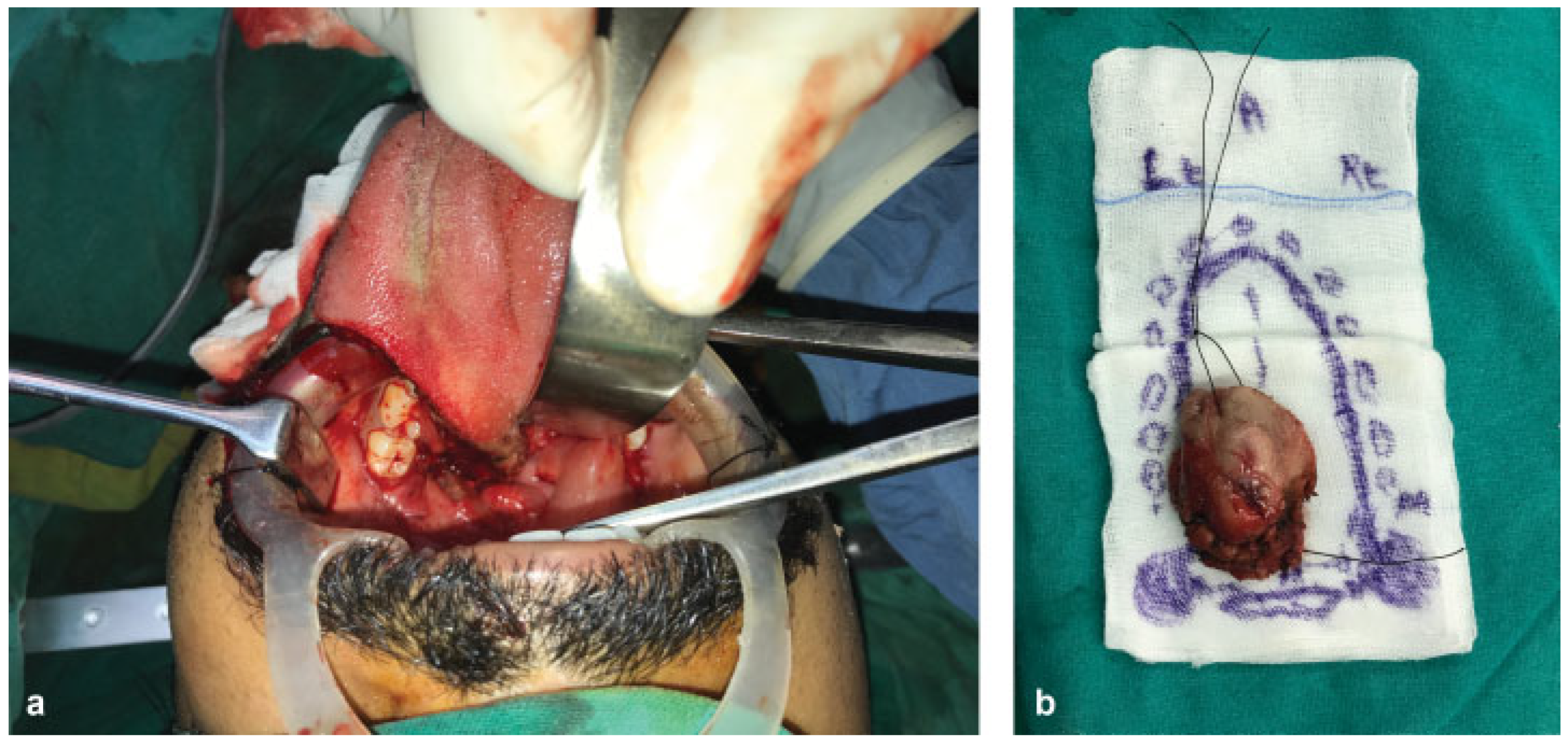

The resulting defect was about 6 × 4 cm extending from the left posterior floor of the mouth to cross the midline of tongue in the horizontal axis and from midoral tongue to the mucosa of the epiglottis in the vertical axis (

Figure 3a,

b). A 7 × 5 cm fascia—cutaneous left radial forearm flap—was harvested after suprafacial dissection, with the pedicle being the radial artery and venae comitantes and the cephalic vein. After flap harvest, inset into the resection defect was performed transorally. The posterior end of the defect was sutured to the flap with parachuted sutures that were placed during the resection. This allowed satisfying inset despite the space constraints associated with the transoral approach. End-to-end anastomosis of the radial artery to left facial artery and of venae comitantes to the left external jugular vein was performed with 8–0 nylon. Due to luminal discrepancy present between the cephalic and other veins in the left side of the neck, end-to-side anastomosis of the cephalic vein to the left internal jugular vein was also performed. Good hemostasis was ensured, drains were placed, and neck incision was closed in layers.

Postoperative Course

The patient tolerated the surgery and early postoperative course well. The tracheostomy was removed on the fifth postoperative day, and the patient could voice and articulate without much difficulty. A detailed swallowing assessment with videofluoroscopy and modified barium swallow (

Figure 4) was performed on the sixth postoperative day, which showed near-normal swallow without signs of penetration or aspiration. He was initially commenced on a blended diet and then upgraded to a soft diet by the eighth postoperative day. A detailed speech and language assessment was performed a month after the surgery, which reported that the patient has intelligible speech with an occasionally noticeable difference and some reduction in accuracy of articulatory movements, but with the normal speed of articulation.

The histopathology of the resected specimen was reported as pT2N0Mx adenoid cystic carcinoma grade I, with clear margins, without perineural or lymphovascular invasion. The patient’s histology was discussed in the tumor board and was planned for adjuvant radiation therapy with a dose of 60 Gy in 30 fractions. The patient continued an oral diet during and after radiation therapy and is currently on the 12th month of his postoperative follow-up (

Figure 5). His speech, swallowing, and tongue movement were excellent.

Discussion

Although the treatment modality of choice for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma has been radiotherapy, in the context of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, primarily surgical resection is becoming increasingly popular. In nonsquamous histology, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma, surgical resection with or without adjuvant radiation is the preferred modality of treatment. The use of robotic surgery for tumors of the oropharynx (tongue base and pharyngeal wall) to avoid a mandibulotomy is an exciting new application.

Surgical treatment of oropharyngeal carcinoma has evolved for the better over the past two decades. Traditional surgical access to tumors involving the base of the tongue was often gained through a lip-splitting mandibulotomy, for adequate margin visualization and reconstruction of surgical defect.[

5] Nevertheless, despite the wide surgical access provided to lesions of the tongue base and tonsil by these anterior mandibulotomy approaches, the shortcomings of such approaches include ensuing alterations of speech and swallowing, malocclusion, wound healing problems, aesthetic deformity, and temporomandibular joint pain.[

6] Furthermore, patients who have undergone tumor resection via a mandibulotomy approach might be at a higher risk of adjuvant radiation–induced side effects of severe trismus and delayed bone healing.[

7,

8,

9]

TORS is well established as a safe and effective form of treatment for base of tongue tumors. It allows a clearer and wider view of the surgical field and better 3D visualization of structures, enabling more comfortable access to the tumor. An additional benefit of TORS is the use of miniaturized tools which imitate standard surgical instruments and arm movements, with tremor filtration. It also permits a frontal view and reaches “blind corners” of the pharyngolaryngeal.[

1,

2] With TORS, we could gain excellent access to the tongue base to excise the tumor with adequate margins, avoiding the functional and cosmetic issues associated with a mandibulotomy. The excellent visualization, exposure, and dexterity help in achieving the exposure that a mandibulotomy would have provided with none of the ensuing complications. However, at times, to achieve the wide surgical margins in case of base of tongue tumors, the docking and movements of the robotic arms may get restricted.

Having resected the tumor, the remnant tongue is likely to have slipped back with the mucosal edges contracting, making flap inset difficult. We avoided this by placing parachuted sutures on the posterior end of the mucosal defect, so that inset was satisfactory despite the limited exposure of the transoral approach. This part of the inset was crucial to avoid postoperative swallowing disturbance. The patient could tolerate oral feeding by the sixth postoperative day and a complete soft diet orally by the eighth postoperative day. This case illustrates how robot-assisted surgery could be used for improved access and ease of resection and reconstruction for optimal outcomes.

Weinstein et al. [

10] have given the contraindications for TORS in oropharyngeal cancer. One of the functional contraindications is tumor resection requiring more than 50% of the deep tongue base musculature. This may not strictly apply in this context of salivary cancers. In such tumors, the preferred modality is surgery, and the extent of the tumor dictates the extent of resection. The resection has to be done even if it crosses the midline. The organ preservation approach such as in oropharyngeal cancer with nonsurgical modalities like chemoradiotherapy is not preferred in such cancers, as in the present case. In this context, robot-assisted surgery helps in reducing the morbidity by avoiding the mandibulotomy.

Conclusion

TORS is an established treatment modality in the management of oropharyngeal cancers. Its use in oral tongue cancers is limited. We report a case of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the base of the tongue where robot-assisted surgery was utilized to achieve adequate resection and functional outcome without the use of a morbid mandibulotomy approach.