Abstract

The aim of this article is to identify the prevalence of posttraumatic psychological symptoms following maxillofacial trauma among an Indian population sample and assess changes in these symptoms over a period of time. Forty-eight adult patients were assessed within 2 weeks of injury with two follow-up visits (4–6 weeks and 12–14 weeks). Patients were administered three self-reporting questionnaires in local language (GHQ-12; HADS; TSQ) on all occasions. Relevant sociodemographic and clinical data were obtained. Forty patients were included in the final analysis. Emotional distress was present in nine participants and five participants satisfied the TSQ criteria for a diagnosis of stress disorder. Anxiety and depression were observed in 10 and 4 patients, respectively. Characteristics associated with abnormal high scores included substance abuse, low education and income levels, facial scars, and complications needing additional intervention. These findings reveal the abnormal psychological response to maxillofacial trauma in immediate and follow-up periods. The use of such screening tools can be considered by the maxillofacial surgeon for early identification of psychological symptoms and referral to the psychiatrist.

India holds the dubious distinction of the largest number of road traffic accidents and maxillofacial injuries are quite common.[1] Current treatment protocols concentrate on the overt manifestation of the physical injury, while the less evident psychosocial sequelae is rarely considered. The psychiatric consequences of posttrauma may range from anxiety and depression, substance abuse or addiction, or posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSDs).[2] Failure to identify and resolve such psychiatric sequelae can result in poor outcome and patient satisfaction. There is a scarcity of information as regard to the psychological after-effects of facial trauma in the Indian population. This is probably due to no exposure to psychiatry as a subject in the undergraduate and postgraduate dental curriculum in India, resulting in low awareness among maxillofacial surgeons. Also, in understaffed surgical units, a relatively quick identification of susceptible patients can allow for early referral to formal psychiatric care. While there has been some scientific work in this topic on the Indian population, none of the studies appear to examine maxillofacial injuries exclusively. This study is among the first few to explore the under-considered psychological sequelae of a maxillofacial injury in an Indian population sample. The objectives of this study are to (1) identify the prevalence of posttraumatic psychological symptoms following maxillofacial trauma, (2) identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with psychological symptoms, (3) assess changes in levels of psychological symptoms over a period of time, and (4) identify patients with potential to develop long-term psychological complications.

Patients and Methods

Participants were recruited over a 15-month period (January 2013 to March 2014) after approvalhad been obtainedfromthe Institute Ethics and Research Committee (IEC/2011/1/12). All adult patients (ages 18–60 years) who reported to the departmentofdentistry ina public sector teaching hospital and level 1 trauma center with a traumatic facial injury resulting in fracture of one or more facial bones were included. Those patients with obvious cerebral impairment, injuries from deliberate self-harm, minor facial injuries, preexisting psychiatric illness, and with injuries beyond the facial region were excluded from the study. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Relevant sociodemographic and clinical data were documented. The participants completed three written questionnaires on three occasions (baseline: within 2 weeks of injury; first follow-up: 4–6 weeks; second follow-up: 12–14 weeks). The questionnaires were forward translated into the native language (Tamil) by a professional translator and back translated into English by a bilingual expert to assess for conformity between the forward translation and the existing version of the questionnaire. These time intervals were as per the protocol followed by the department for recall review of patients. As most patients were daily wage earners, review appointments were designed to minimize loss of earning and out-of-pocket expenditure on travel. The first follow-up questionnaire was administered when patients usually report for arch bar removal. The second follow-up questionnaire was administered when patients were assessed for possible dental rehabilitation with restorative procedures and dentures.

General Health Questionnaire-12

The General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) focuses on 12 indicators of psychological morbidity and is used to identify the severity of psychological distress experienced by an individual within the past few weeks. Scoring was done using the simple Likert scale of 0–1–2–3, and a total score of 12 and above was considered as abnormal.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a 14-item questionnaire with anxiety and depression subscales. Each subscale has a score range of 0 to 21 with a score above 7 indicative of disorder.

Trauma Screening Questionnaire

The Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ) is a 10-item symptom screen for PTSD and has five reexperiencing items and five arousal symptoms of PTSD in a simple yes/no format. A “yes” score in six or more items was considered as abnormal.

The results were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 19) and a p-value of ≤ 0.5 was considered significant. While all participants were included for analysis of demographic and clinical data, only those who completed the questionnaires at all three periods were included for the analysis of psychological outcomes. ANOVA test was performed to determine the association, if any, between the demographic and clinical data and abnormal scores. A linear regression model was employed to assess predictive risk factors for persistent abnormal psychological response following facial injury.

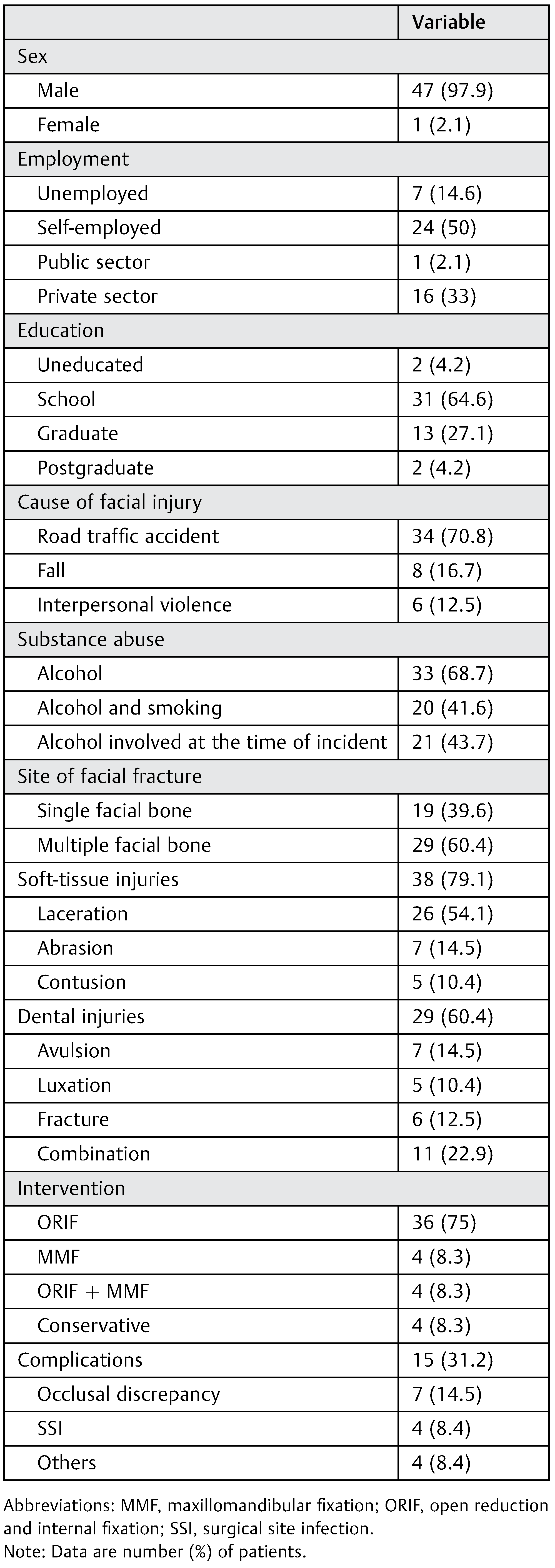

A total of 48 patients were recruited in this study period. Of these, 41 patients completed the measurements at all three intervals. One patient was excluded after completion of the final questionnaire due to bereavement in the family during the study period. The study group was almost exclusively male with only a single female participant. The mean age of the participants was 29.04 years (SD 8.12 years; range, 18–48 years). Twenty-seven patients were married with a single divorcee. All married patients had one or more child except a single participant who was childless. A majority of the participants (n = 44) were educated to at least basic schooling or above. More than 80% were employed as daily wage earners performing low-skilled work. The leading cause of injury was road traffic accidents (70.8%). Associated soft-tissueand dental injuries were observed in a majority of patients. Twenty-one participants were under the influence of alcohol at the time of facial injury. Open reduction and internal fixation of facial fractures were performed in 36 patients. Fifteen patients reported with complications during the follow-up and required additional intervention in the form of medications/ surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical details of participants (n = 48).

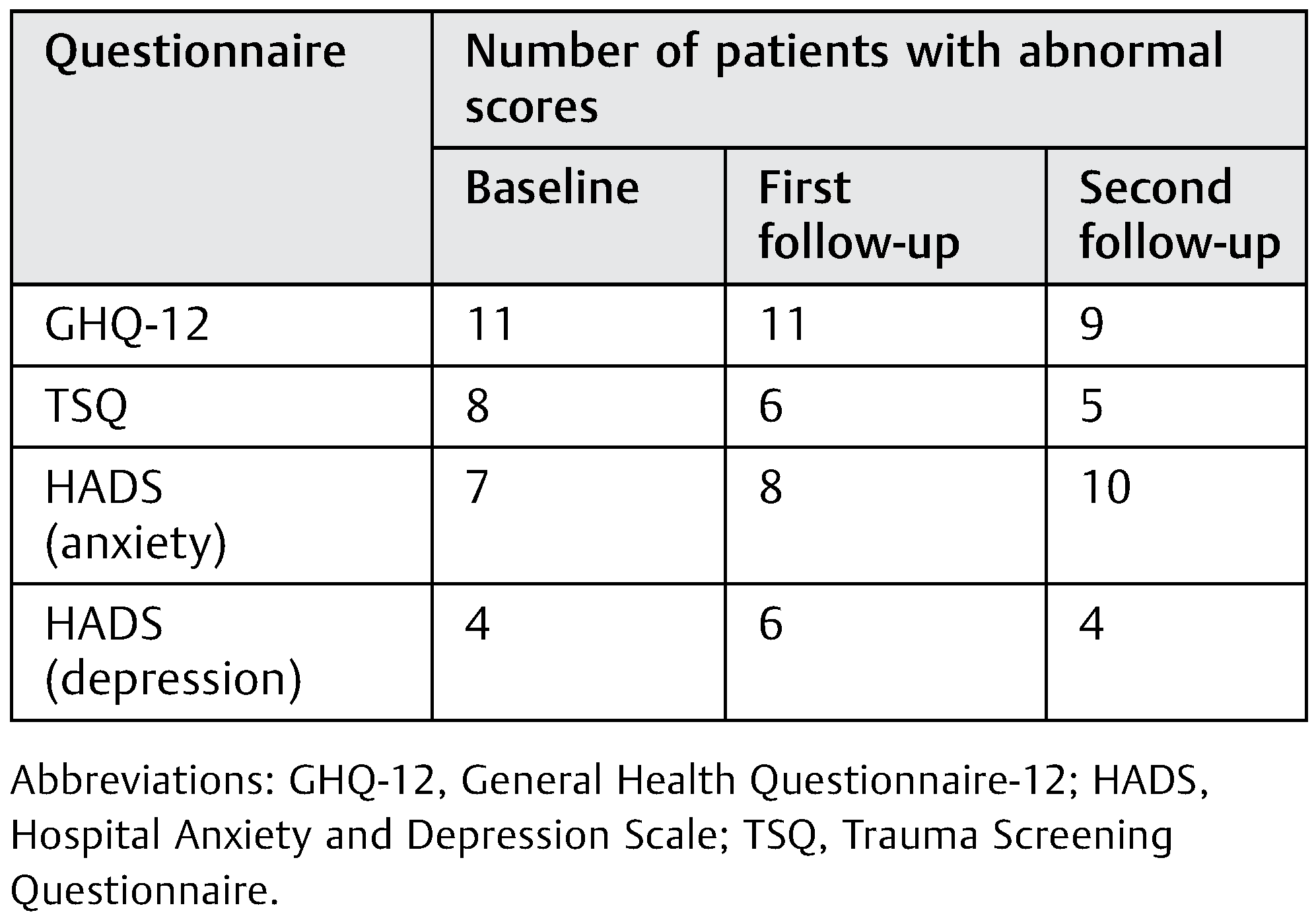

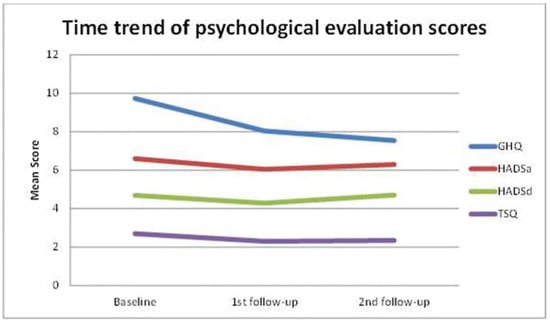

The mean score for the administered questionnaires for the three visits is depicted in Figure 1. While improvement or worsening of scores was seen in a few patients, abnormal scores were also reported in new patients at follow-up visits. At the end of last follow-up, emotional distress was present in nine participants and five participants satisfied the TSQ criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD. Anxiety and depression were observed in 10 and 4 patients, respectively (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Time trend of psychological evaluation scores. GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; HADSa, Hospital Anxiety Scale; HADSd, Hospital Depression Scale; TSQ, Trauma Screening Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Patients with abnormal psychological scores.

A statistically significant association with abnormal scores was observed with substance abuse (p = 0.2), the presence of facial scars and dental injuries (p = 0.2), low skilled daily wage earners (p = 0.1), and in complications requiring additional intervention (p = 0.06). These factors were also predictive for persistent psychological issues in facial injury patients (R2 > 0.90).

Discussion

Varied responses have been observed with regard to the psychological adjustment to acquired facial trauma. Most studies report significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression among facial trauma patients (13–40%) at baseline and follow-up periods (1 monthto 1 year).[3,4,5] Ukpongetalobserved symptoms of depression in 48% (baseline) and 22% (10–12 weeks) among a cohort of Nigerian patients with facial trauma.[6] They concluded that scarring might be the cause of continuing depression serving as a constant reminder of the incident in which the injury was sustained. However, Hull et al in a prospective study of 39 patients with maxillofacial trauma reported a decrease in both depression levels (baseline: 14%; 1-month follow-up: 4%) and anxiety levels (baseline: 15%; 1-month follow-up: 7%).[7] This variable response has been attributed to several factors such as patient’s social support, preexisting psychological disorders, substance abuse, and postoperative pain.[8] Even the cause of facial trauma may have a differential effect on the psychological consequence with injuries sustained as a result of assault associated with poor psychological outcomes.[9] An important factor in recovery from any trauma is family support. Even during follow-up visits, most ofour patients are almost always accompanied by relatives who are anxious to provide appropriate care to ensure a speedy recovery. It is indicative of the good social support that a joint family system in India can provide. The cultural attitude toward illness, recovery, and the sick person’s role, work, and disability are other factors that would help or impede this process.[10]

PTSD is an anxiety disorder that results from exposure to an event that is threatening to one’s life or physical integrityand is reflected in three clusters of symptoms: (1) reexperiencing (e.g., nightmares and flashbacks), (2) avoidance/numbing (e.g., avoidance of reminders of the event and feelings of detachment), and (3) hypervigilance (e.g., irritability and sleep disturbances).[11] A diagnosis of PTSD is made when symptoms persist beyond 30 days and is associated with impairment in social and occupational functioning.

In the developed world, PTSD prevalence rates range from 1 to 14% of the general population and 7.3 to 23.6% of the population exposed to assaults, disasters, or severe accidents.[12] The independent predictors of PTSD are female gender, marital status for males, preexisting psychiatric conditions, substance abuse, lower socioeconomic status, previous exposure to trauma, lack of postexposure social support, and adjustment.[13] Bisson et al[9] reported a PTSD of 27% among 66 patients with facial trauma 7 weeks after the injury. Other workers have reported PTSD levels ranging from 10 to 44% for up to 9 months following facial injuries with high absolute levels of PTSD at the initial stages.[11,14,15]

PTSD data in Indian population are limited with psychological consequences of road traffic accidents reported to range from 8.5 to 39%.[16] Undavalli et al[17] in a study of PTSD among post–road traffic accident patients requiring hospitalization in India observed a “three-hit” phenomenon, namely, hospital expenditure due to trauma; time away from work during hospitalization and recovery which results in loss of income; and finally, a reduction in performance due to PTSD which may lead to loss of work, which a road traffic accident victim experiences in the posttrauma period and these hits are significant factors resulting in a financial crisis and worsening of the psychological state. In a study involving 460 patients in an Indian city, a statistically significant relationship was observed between higher levels of PTSD in the 153 patients with disfiguring facial injuries and those with nondisfiguring facial injuries and orthopaedic injuries.[18] Despite the logical conclusion that severe injuries are more likely to precipitate PTSD, the scientific evidence is unclear, with PTSD observed even in those with minor facial injuries.[11,19] It is not necessary that all traumatic event should invariably lead to the development of a psychological disorder. Many patients are quite resilient and often appear to cope well following the traumatic event. The factor that seems to be responsible for the development of PTSD is the subjective perception of the injury.[20] Laskin[21] opined that the patient’s subjective perception is a more important determinant of adjustment to facial trauma than any objective measure of the deformity and that those who overestimate the degree of disfigurement generally show the greatest psychological maladjustment. Some patients may be extremely sensitive to minor changes in facial appearance following trauma and request secondary corrective surgery for imperfections that, in the eyes of a surgeon, are of negligible surgical importance.

Units that work with trauma patients should be able to identify and respond to the psychological needs of the individual patient. However, it has been observed that staffs working within facial trauma units often fail to detect, document, and treat the psychological symptoms due to limited knowledge of the possible psychological sequelae.[15] In a survey among oral and maxillofacial surgeons, 95% of surgeons had experienced patients with posttraumatic psychological morbidities, with close to 60% disclosing a moderate or high level of relevant knowledge.[22] Despite such high numbers, only a quarter had access to intra-service psychological staff. In another survey examining the perceptions of surgeons who treat facial injuries, less than 50% felt that the psychosocial welfare of their patients was adequately addressed in their hospital setting.[23] Lack of resources, namely, financial, space, and personnel constraints, is determined as the most important barrier to the implementation of psychosocial aftercare.[4] These limitations are only but amplified in crowded public sector hospitals in developing countries like India.

The clinical implications of unmet psychological needs can be subtle, yet profound. Unmet psychological needs in facially injured patients can potentially complicate physical recovery by adversely impacting on patient compliance and subsequent follow-up attendance.[7] Poor adherence to postoperative instructions such as in maxillomandibular fixation may force the surgeon to consider a more expensive option of internal fixation. Neurobiological research on PTSD shows an atypical response to stress with dysregulation of the hypothalamic– pituitary–axis, catecholamine system, endogenous opioid system, and the immune response to trauma.[24] PTSD may also have implications on wound healing due to a chronic disturbance in homoeostasis which could result in prolonged postoperative pain and increased drug dependence.[15] Furthermore, delayed healing may also encourage harmful habits such as substance abuse and predispose to maladjustment.

There are several shortcomings to this study. First, the sample (recruited from a single center) is moderately sized with a dropout rate of 16%. However, this sample size results in a power of 77.6% for detection for anxiety and depression, which is acceptable for a preliminary study. A large number of patients who reported with maxillofacial injuries to our hospital often had other associated injuries, thereby precluding their inclusion in this study and was the primary reason for the sample size. Second, as this hospital caters mainly to the medical needs of the underprivileged and lower socioeconomic strata, the influence of the socioeconomic condition on abnormal scores must be interpreted with caution due to the inherent bias in our patient population. Further, chronic alcoholism among this group could predispose them to high-risk behavior such as driving under influence of alcohol and not wearing protective helmets. Third, we were unable to ensure that no patient with a preexisting psychiatric condition was inadvertently recruited for this study, as most patients report with almost no supporting documents for earlier treatments. Also, baseline data were usually taken 7 to 10 days after the injury which may have resulted in nonidentification of acute stress reactions. Fourthly, data collected relied on self-reporting measures which meant that the questionnaire could be administered only to those who were literate in the Tamil language. The possibility of bias and misrepresentation cannot be entirely ruled out. Lastly, patients with minor injuries were not included as, during the pilot phase of this study, it was noticed that patients with such injuries failed to follow-up. A majority of patients happen to be daily wage earners and report to this hospital from large distances. We speculate that once the acute phase of a minor injury is satisfactorily managed, such patients due to financial and time constraints may not find it easy to be compliant with follow-up protocol of this study. Again, those with severe injuries precluding informed consent or extensive surgery were also excluded. Despite these limitations, this study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first from the Indian subcontinent, to examine the psychological consequences of injuries exclusive to the maxillofacial region.

Conclusions

The questionnaires used in the study are validated and internationally accepted screening tools for psychological distress and can be administered in a short period. The 1-month follow-up period is the best time to assess the patient, as many of the transient stress reactions would have diminished by then.[16] Scores beyond a threshold are categorized as “abnormal,” meaning that it is suggestive of a psychiatric issue and may need further evaluation by a psychiatrist if deemed necessary. Abnormal scores at the initial presentation can be attributed to preoperative pain, discomfort, and compromised mastication and deglutition. A downward trend of the mean scores of all administered questionnaires was seen in the first follow-up and can be explained by the expected improvement in oral function following corrective surgery for the facial fracture. Abnormal scores in this period would tag the patient as potential for long-term psychological sequelae and must be monitored at regular intervals. Persistent abnormal scores at 12- to 14-week intervals can no longer be attributed to transient postsurgery discomfort and will warrant a formal psychiatry evaluation. Even if normal scores are observed in high-risk individuals (substance abuse, healing complications, and associated facial and dental injuries as observed in this study) at the 1-month period, a recall evaluation is recommended to confirm normality.

The detection of abnormal scores in a quarter of the study population is indicative of the prevalence of this neglected complication following facial injury. Surgeons should not hesitate to utilize the services of a psychiatrist, whenever available, especially for those patients who exhibit certain key interpersonal behaviors.[25] While this study identified high-risk patients as those with a history of substance abuse, facial scars, and needing further intervention to address complications, more research is needed in the Indian population to identify patients with a facial injury who have potential for long-term psychological complications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. G. Ezhumalai, Department of Biostatistics, Sri Balaji Vidyapeeth University, Pondicherry, India, for his help.

References

- Kaul, R.P.; Sagar, S.; Singhal, M.; Kumar, A.; Jaipuria, J.; Misra, M. Burden of maxillofacial trauma at level 1 trauma center. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2014, 7, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seethalakshmi, R.; Dhavale, H.S.; Gawande, S.; Dewan, M. Psychiatric morbidity following motor vehicle crashes: a pilot study from India. J Psychiatr Pract 2006, 12, 415–418. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, P.; Ross, N.; Rogers, S. Recovering maxillofacial trauma patients: the hidden problems. J Wound Care 2001, 10, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.; Ahmed, M.; Walton, G.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Hoffman, G.R. The association between depression and anxiety disorders following facial trauma–a comparative study. Injury 2010, 41, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lento, J.; Glynn, S.; Shetty, V.; Asarnow, J.; Wang, J.; Belin, T.R. Psychologic functioning and needs of indigent patients with facial injury: a prospective controlled study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004, 62, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ukpong, D.I.; Ugboko, V.I.; Ndukwe, K.C.; Gbolahan, O.O. Health-related quality of life in Nigerian patients with facial trauma and controls: a preliminary survey. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008, 46, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, A.M.; Lowe, T.; Devlin, M.; Finlay, P.; Koppel, D.; Stewart, A.M. Psychological consequences of maxillofacial trauma: a preliminary study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003, 41, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, A. Psychological issues in acquired facial trauma. Indian J Plast Surg 2010, 43, 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bisson, J.I.; Shepherd, J.P.; Dhutia, M. Psychological sequelae of facial trauma. J Trauma 1997, 43, 496–500. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, S.M.; Laskin, D.M.; Kiesler, D.J.; Wilson, M.; Rajab, B.; Campbell, T.A. Psychological factors associated with response to maxillofacial injury and its treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008, 66, 755–761. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, S.M.; Asarnow, J.R.; Asarnow, R.; et al. The development of acute post-traumatic stress disorder after orofacial injury: a prospective study in a large urban hospital. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003, 61, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C. Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. J Clin Psychiatry discussion 13–14. 2000, (Suppl. S5), 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev, A.Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder and stress-related disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2009, 32, 687–704. [Google Scholar]

- Roccia, F.; Dell’Acqua, A.; Angelini, G.; Berrone, S. Maxillofacial trauma and psychiatric sequelae: post-traumatic stress disorder. J Craniofac Surg 2005, 16, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, S.M.; Shetty, V. The long-term psychological sequelae of orofacial injury. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2010, 22, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Joshipura, M.K. Trauma care in India: current scenario. World J Surg 2008, 32, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Undavalli, C.; Das, P.; Dutt, T.; Bhoi, S.; Kashyap, R. PTSD in post-road traffic accident patients requiring hospitalization in Indian subcontinent: a review on magnitude of the problem and management guidelines. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2014, 7, 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Prashanth, N.T.; Raghuveer, H.P.; Kumar, R.D.; Shobha, E.S.; Rangan, V.; Hullale, B. Post-traumatic stress disorder in facial injuries: a comparative study. J Contemp Dent Pract 2015, 16, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch, M.D.; Gould, L.J.; Dzwierzynski, W.W.; Larson, D.L. Psychological impact of traumatic injuries: what the surgeon can do. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002, 109, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jeavons, S. Predicting who suffers psychological trauma in the first year after a road accident. Behav Res Ther 2000, 38, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskin, D.M. The psychological consequences of maxillofacial injury. (Editorial) J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999, 57, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitak-Arnnop, P.; Hervé, C.; Coffin, J.C.; Dhanuthai, K.; Bertrand, J.C.; Meningaud, J.P. Psychological care for maxillofacial trauma patients: a preliminary survey of oral and maxillofacial surgeons. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2011, 39, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zazzali, J.L.; Marshall, G.N.; Shetty, V.; Yamashita, D.D.; Sinha, U.K.; Rayburn, N.R. Provider perceptions of patient psychosocial needs after orofacial injury. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007, 65, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Pervanidou, P.; Chrousos, G.P. Neuroendocrinology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Prog Brain Res 2010, 182, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger, J.C.; Davidson, J.R.; Lecrubier, Y.; et al. Consensus statement update on posttraumatic stress disorder from the international consensus group on depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry 2004, 65 (Suppl 1), 55–62. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author. The Author(s) 2017.