Abstract

Fracture of the clavicle following radical neck dissection (RND) and/or radiotherapy is a rare complication. Several causes of fracture of the clavicle after treatment of head and neck cancer were postulated in previous reports. We present a case of fracture of the clavicle after treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. An 81-year-old Japanese woman underwent RND, subtotal glossectomy, reconstruction using a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap (PMMCF), and postoperative radiotherapy (50.4 Gy). One month after the primary treatment, fracture of the clavicle occurred. It was thought that muscular dynamic factor and reduction of blood supply in the clavicle associated with RND and PMMCF were the causes of the fracture. We have to recognize the occurrence of this complication and try to reduce the factors related to the complication.

Radical neck dissection (RND) followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy has been a common treatment strategy for advanced head and neck cancer. In patients with some problems such as general illness, reconstruction of the surgical defect using a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap (PMMCF) is still a feasible option. Fracture of the clavicle has been reported as one of the rare complications after RND and the incidence is approximately 0.4 to 0.5% [1]. Strauss et al reported that RND and/or radiotherapy result in weakening of the bone and blood supply that subsequently cause fracture of the clavicle [2]. Previously reported PMMCF-related complications included fistula, partial necrosis, infection, dehiscence, hematoma, seroma, and total necrosis [3,4]. Only one report described the association between fracture of the clavicle and PMMCF [5].

We present a rare case of the fracture of the clavicle following surgery that involved RND and reconstruction by PMMCF and adjuvant radiotherapy for tongue carcinoma.

Case Report

An 81-year-old Japanese woman with squamous cell carcinoma on the left side of the tongue was referred to our department. The tumor extended over a midline contralaterally and a swollen lymph node in Level IIA with fixation around soft tissue, which contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed, was palpable. The lesion was staged as cT3N1M0 according to the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors (7th Edition, UICC) [6]. But there were two lymph nodes with an irregular contrast effect in Levels IIA and B in contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging besides the obvious metastatic lymph node by contrast-enhanced CT that were suspected lymph node metastases (Figure 1). Therefore, RND, subtotal glossectomy, and simultaneous reconstruction using a PMMCF were performed. The PMMCF was elevated from the chest wall and moved upward. The clavicular periosteum around the pectoral branches of the thoracoacromial vessels was excised from the cervical and thoracic sides, and the periosteum on the inferior surface of the clavicle was detached and reflected to drop it downward [7,8]. The PMMCF was brought to the oral cavity via the subclavian route for reconstruction of the defect of the tongue (Figure 2).

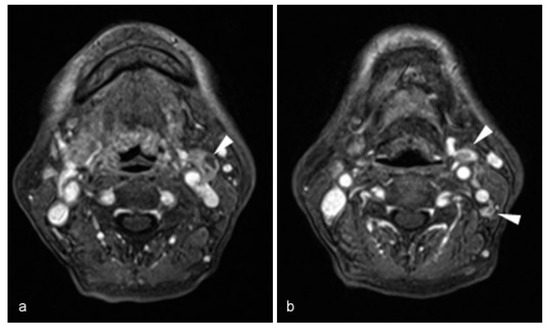

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced MRI (axial T1-weighted images, fat suppression, gadolinium enhancement) showed metastatic and metastases suspicious lymph node in Levels II A and B. (a) Fixed swollen lymph node detected contrast-enhanced CT (arrow head). (b) Two no swollen lymph nodes with irregular contrast effect (arrow head).

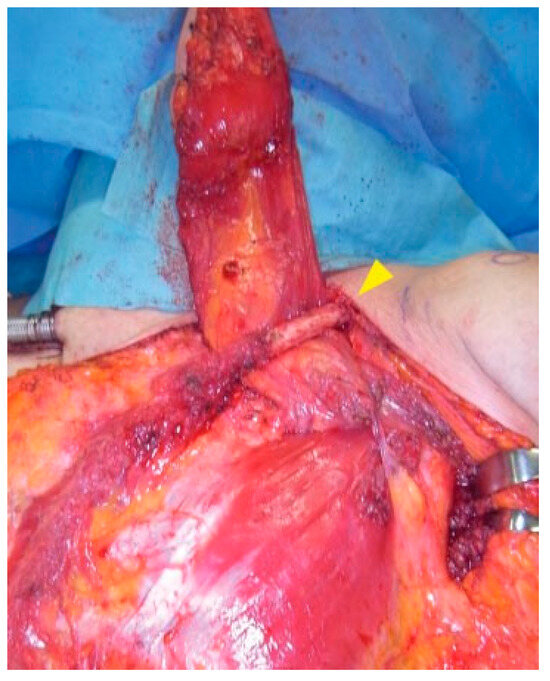

Figure 2.

Bringing pectoralis major myocutaneous flap to the oral cavity via the subclavian root (arrowhead: left clavicle).

The surgical specimen showed lymphatic, vascular, and perineural invasions in the primary lesion and multiple cervical lymph node metastases. Consequently, postoperative radiotherapy to the primary site and whole neck was scheduled. Concurrent chemotherapy was not administered because of her renal dysfunction. The primary and cervical site was irradiated at a dose of 50.4 Gy. The supraclavicular site and whole clavicle were not irradiated (Figure 3).

One month after postoperative radiotherapy, the left clavicle was fractured when she raised her left hand and took hold of the handrail of a flight of stairs. She complained of limitation in her left shoulder movement without any pain and was referred to the department of orthopedics. Physical examination showed anteromedial displacement of her left shoulder. X-ray and CT scan revealed a fracture at the inner two-thirds of the clavicle (Figure 4). The patient chose con-servative treatment.

Figure 3.

Radiation field of the primary and cervical sites. The whole clavicle was outside the radiation field.

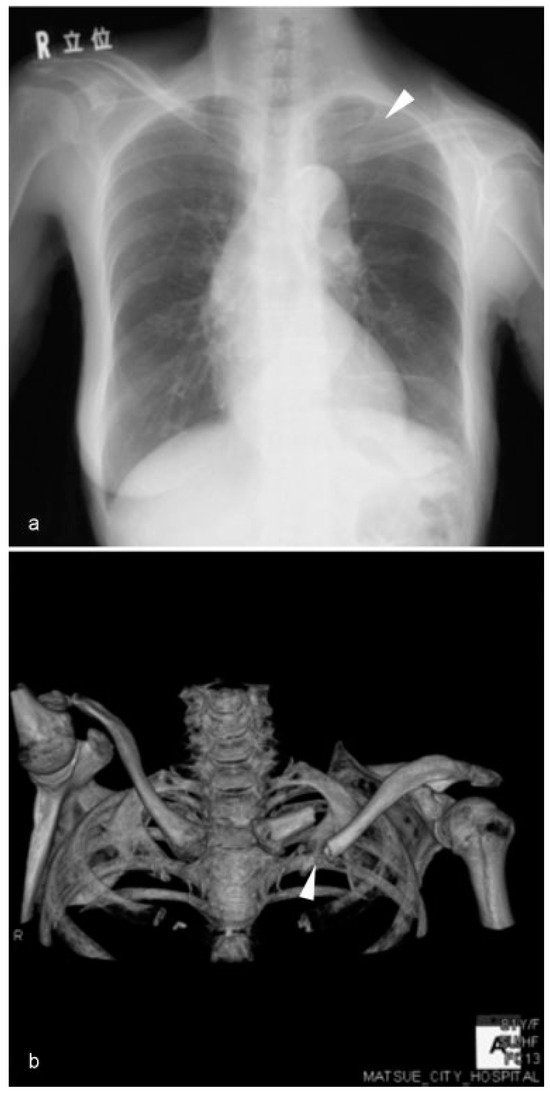

Figure 4.

Chest X-ray (a) and 3DCT (b) showed a fracture of the left clavicle (arrowhead).

Six months later, tumor reoccurred in the left floor of the mouth. Chemotherapy with 5-FU, cisplatin, and cetuximab (FP + Cmab) was planned, but an infusion reaction caused by Cmab (Grade III–IV, CTCAE version 4.0) occurred. Therefore, the FP + Cmab regimen was changed to FP regimen. After one course of the FP regimen, her performance status become worse and the patient received best supportive care. The patient died of recurrent tumor 15 months after primary treatment.

Discussion

Fracture of clavicle following RND is a rare, late postoperative complication, which is one of the pathological conditions in the clavicular region including infection, osteonecrosis, dislocation, and hypertrophy of the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) [9,10]. With an incidental swelling, it has been also reported as a pseudotumor [11]. When a slow growing mass in the SCJ occurs after RND, recurrent or metastatic disease, postradiation sarcoma, and infection should be ruled out. If a neoplastic lesion is suspected, a biopsy is essential [11,12,13]. Imaging modalities also play an important role in the assessment and management of fracture of the clavicle after RND [14]. Previous reports pointed out the following causes of fracture of the clavicle after treatment of head and neck cancer: (1) avascular necrosis of clavicle after RND, (2) dislocation of the shoulder position after RND, (3) imbalance of the muscles associated with the clavicle after RND, (4) influence of radiation therapy such as ostitis and osteonecrosis, and (5) reduction of blood supply associated with PMMCF harvesting and leading the flap to the oral cavity via the subclavian route.

Temesvari and Vandor postulated that the reason was avascular necrosis due to poor blood supply following resection of the sternocleidomastoid muscle [13]. However, Ord and Langdon stated that stripping of the sternocleidomastoid muscle alone is unlikely to cause avascular necrosis, and ligation of the suprascapular artery, which is a nutrient artery to the clavicle, in lower neck dissection could be a cause [9].

The muscles attached to the clavicle consist of the sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, deltoid, subclavius, and pectoralis major muscles. In classical RND, the sternocleidomastoid muscle and accessory nerve are sacrificed. Shoulder symptoms occur in 18 to 70% of patients in modified neck dissection and 29 to 39% of patients in selective neck dissection that spinal accessory nerve has been spared [15]. The sacrifice or injury of the accessory nerve results in paralysis of the trapezius muscle. RND disrupts the balance between cranial traction and caudal traction. Therefore, downward contraction of pectoralis major is unopposed and a vertical stress fracture of the clavicle might occur [5,11,16]. Paralysis of the trapezius muscle results in the drooping of the shoulder. Shoulder drooping tends to pull the lateral clavicle down and therefore the medial clavicle is mobilized upward and forward, and the increased weight of the upper limb is no longer upheld by the trapezius muscle [10,11,17].

Fracture of the clavicle following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma and Hodgkin’s disease has previously been reported [18,19]. Bone change after radiotherapy is quite common. Bone complications related to radiotherapy include pathological fracture, bone sequestrum, and bone necrosis, which result from damage of the blood supply [2]. Particularly, the risk of fracture of the clavicle would be increased when RND and radiotherapy are performed.

Koh et al reported the injury of the periosteum on the inferior surface of the clavicle at the time of elevation of PMMCF as a possible cause of fracture of the clavicle. Because the blood supply of the bone is usually through its periosteum and surrounding muscles, the injury of its periosteum and division of the overlying pectoralis major muscle might damage the blood supply of the clavicle and result in malnutrition of the clavicle [5].

In our case, trauma and metastasis in the clavicle were not recognized, and the subclavicular site and whole clavicle were not irradiated. Therefore, a muscular dynamic factor, dislocation of the shoulder position, and reduction of blood supply associated with RND and PMMCF are thought to be the causes of the fracture of the clavicle. However, wide periosteal stripping, which is needed to lead the bulky island of PMMCF to the oral cavity via the subclavian route, would be considered to increase the risk of the fracture.

When this complication occurs, the patient has little pain in the clavicular site and our patient had no complaint of pain. The reason for this is resection of the superficial branches of the cervical plexus (C2–4). This would be followed by reduced sensitivityof the periosteumof the clavicle and SCJ becausethe supraclavicular nerve is derived from C4 [9].

Trapezius muscle is innervated by accessory nerve and cervical plexus. Previous studies have reported that motor input from the cervical plexus to the trapezius muscle was provided in 32 to 75% of cases [20,21,22,23]. Kim et al demonstrated that the trapezius muscle receives a motor input from C4 in 83% of cases, C3 in 46% of cases, and C2 in 8% of cases [24]. Moreover, Pu et al histochemically revealed the presence of the motor nerve in the cervical plexuses that elicited no response to stimulation by electroneurography. They also suggested that intraoperative trauma and tension create dysfunction of some nerves [25]. Although C2, C3, and C4 inconsistently provide motor input to the trapezius muscle, careful preservation of these cervical plexus in RND would contribute to prevention of the pathological conditions affected in the clavicular region, which include fracture of the clavicle, dislocation, or hypertrophy of the SCJ by minimization of shoulder syndrome.

Conclusions

Fracture of the clavicle is a rare complication following treatment of head and neck cancer, but we have to recognize the occurrence of the fracture as a phenomenon resulted from the pathological conditions affected in the clavicular region and try to reduce the factors related to this complication to maintain of quality of life after the treatment.

References

- Lörz, M.; Bettinger, R.; Desloovere, C.; Leppek, R. Clavicular fractures after radical neck dissection [in German]. HNO 1991, 39, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, M.; Bushey, M.J.; Chung, C.; Baum, S. Fracture of the clavicle following radical neck dissection and postoperative radiotherapy: A case report and review of the literature. Laryngoscope 1982, 92, 1304–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenović, A.; Virag, M.; Uglesić, V.; Aljinović-Ratković, N. The pectoralis major flap in head and neck reconstruction: First 500 patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2006, 34, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vartanian, J.G.; Carvalho, A.L.; Carvalho, S.M.; Mizobe, L.; Magrin, J.; Kowalski, L.P. Pectoralis major and other myofascial/myocutaneous flaps in head and neck cancer reconstruction: Experience with 437 cases at a single institution. Head Neck 2004, 26, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, Y.W.; Choi, E.C.; Lim, Y.C.; Lee, S.W. Fracture of the clavicle following the island type of pectoralis major myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of head and neck defect. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007, 264, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobin, L.H.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Wittekind, C. International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 7th ed.; Wiley-Liss: New York, 2010; pp. 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokawa, K.; Tai, Y.; Tanabe, H.Y.; et al. A method that preserves circulation during preparation of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap in head and neck reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998, 102, 2336–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, T.; Nariai, Y.; Tatsumi, H.; Karino, M.; Yoshino, A.; Sekine, J. A modified pectoralis major myocutaneous flap technique with improved vascular supply and an extended rotation arc for oral defects: A case report. Oncol Lett 2015, 10, 2739–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, R.A.; Langdon, J.D. Stress fracture of the clavicle. A rare late complication of radical neck dissection. J Maxillofac Surg 1986, 14, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantlon, G.E.; Gluckman, J.L. Sternoclavicular joint hypertrophy following radical neck dissection. Head Neck Surg 1983, 5, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini-Storchi, O.; Lo Russo, D.; Agostini, V. ‘Pseudotumors’ of the clavicle subsequent to radical neck dissection. J Laryngol Otol 1985, 99, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfpenny, W.; Goodger, N. Early fracture of clavicle following neck dissection. J Laryngol Otol 2000, 114, 714–715. [Google Scholar]

- Temesvari, A.; Vandor, F. Complications after cervical dissections [in German]. Chirurg 1954, 25, 437–443. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, T.; Kitajima, K.; Saito, M.; Otsuki, N.; Nibu, K.; Sugimura, K. Insufficiency fracture of the clavicle after neck dissection: Imaging features. Jpn J Radiol 2014, 32, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bradley, P.J.; Ferlito, A.; Silver, C.E.; et al. Neck treatment and shoulder morbidity: Still a challenge. Head Neck 2011, 33, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cummings, C.W.; First, R. Stress fracture of the clavicle after a radical neck dissection; Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg 1975, 55, 366–367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gorman, J.B.; Stone, R.T.; Keats, T.E. Changes in the sternoclavicular joint following radical neck dissection. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1971, 111, 584–587. [Google Scholar]

- Howland, W.J.; Loeffler, R.K.; Starchman, D.E.; Johnson, R.G. Postirradiation atrophic changes of bone and related complications. Radiology 1975, 117 (3 Pt 1), 677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Spar, I. Total claviculectomy for pathological fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977, 129, 236–237. [Google Scholar]

- Soo, K.C.; Strong, E.W.; Spiro, R.H.; Shah, J.P.; Nori, S.; Green, R.F. Innervation of the trapezius muscle by the intra-operative measurement of motor action potentials. Head Neck 1993, 15, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenberg Lind, C.; Lundberg, B.; Hammarstedt Nordenvall, L.; Heiwe, S.; Persson, J.K.; Hydman, J. Quantification of trapezius muscle innervation during neck dissections: Cervical plexus versus the spinal accessory nerve. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2015, 124, 881–885. [Google Scholar]

- Nori, S.; Soo, K.C.; Green, R.F.; Strong, E.W.; Miodownik, S. Utilization of intraoperative electroneurography to understand the innervation of the trapezius muscle. Muscle Nerve 1997, 20, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gavid, M.; Mayaud, A.; Timochenko, A.; Asanau, A.; Prades, J.M. Topographical and functional anatomy of trapezius muscle innervation by spinal accessory nerve and C2 to C4 nerves of cervical plexus. Surg Radiol Anat 2016, 38, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, K.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, D.J.; Park, B.J.; Rho, Y.S. Motor innervation of the trapezius muscle: Intraoperative motor conduction study during neck dissection. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2014, 76, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Y.M.; Tang, E.Y.; Yang, X.D. Trapezius muscle innervation from the spinal accessory nerve and branches of the cervical plexus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008, 37, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the author. The Author(s) 2017.