To Hide Behind the Mask of Mandates: Disguised Opinion Shopping Under Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation and Retention in Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

1.2. Significance of the Study

2. Background and Prior Literature

2.1. Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation and Retention in Korea

2.2. Opinion Shopping Literature

2.2.1. Opinion Shopping Under Voluntary Settings

2.2.2. Opinion Shopping Under Tenure Mandates

2.3. Audit Quality Literature

2.3.1. Audit Quality Under Voluntary Settings

2.3.2. Audit Quality Under Tenure Mandates

Cross-Jurisdictional Evidence on Mandatory Tenure

Empirical Findings from Korea’s Auditor Rotation and Retention

3. Hypothesis Development

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample and Data

4.2. Data Collection and Coding Procedures

4.3. Justification of Sample Period

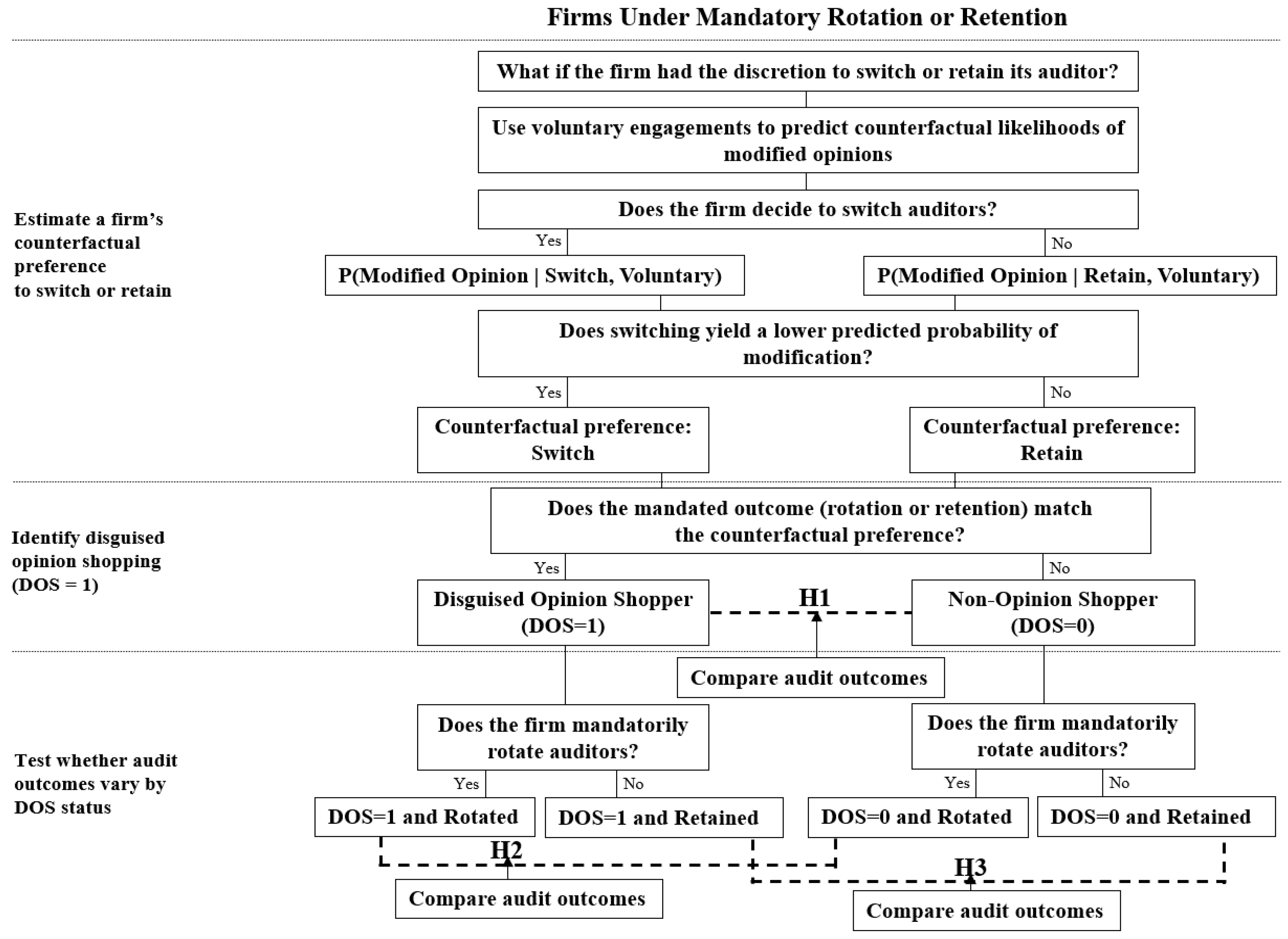

4.4. Estimating Counterfactual Auditor Switching Preferences Under Tenure Mandates

4.5. Identifying Disguised Opinion Shopping

5. Empirical Analyses

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Disguised Opinion Shopping and Audit Opinion Outcomes

5.3. Disguised Opinion Shopping and Audit Quality

5.4. Voluntary Auditor Selection in the Post-Mandate Period

6. Additional Analyses

6.1. Sensitivity of Audit Quality Outcomes to Modified Opinion Classification

6.2. Alternative Thresholds for Inferring Firms’ Auditor Preference: Switch vs. Retain

7. Discussion and Contribution to Knowledge

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Definition of Variables

| Variables | Definition | |

| Audit Opinion Model (1) | ||

| MO | = | 1 if a firm receives a modified opinion, i.e., an unqualified opinion with harmful explanatory language, qualified opinion, disclaimer of opinion, and adverse opinion, and 0 otherwise; |

| MOLAG | = | 1 if a firm receives a modified opinion in the prior year, i.e., an unqualified opinion with harmful explanatory language, qualified opinion, disclaimer of opinion, and adverse opinion, and 0 otherwise; |

| SIZE | = | the natural logarithm of total assets; |

| LEV | = | total debt divided by total assets; |

| LIQ | = | current assets divided by current liabilities; |

| LOSS | = | 1 for firms reporting losses in the current year, and 0 otherwise; |

| BM | = | book value of equity divided by market value of equity; |

| ISSUANCE | = | 1 if a firm issues debt or equity securities in the current year, and 0 otherwise; |

| OCF | = | operation cash flows divided by the previous year’s total assets; |

| BIGN | = | 1 if the Big N audit firms perform the audit, 0 otherwise; |

| RETURN | = | the compounded stock return over the fiscal year; |

| VOLATILITY | = | the standard deviation of residuals of the market model; |

| PROF | = | net income before extraordinary items scaled by total assets; |

| S | = | 1 if a firm switches an auditor, and 0 otherwise; |

| MAND | = | 1 if a firm is subject to mandatory auditor rotation or retention, and 0 otherwise. |

| Reported Modified Opinion Model (2) | ||

| DOS | = | 1 if the firm’s predicted preferences on auditor selection align with regulatory requirements, and 0 otherwise; |

| DOS_SWITCH | = | 1 if the firm’s predicted preference is to switch auditors and it is subject to mandatory rotation, and 0 otherwise; |

| DOS_RETAIN | = | 1 if the firm’s predicted preference is to retain its auditor and it is subject to mandatory retention, and 0 otherwise; |

| DE | = | the ratio of long-term debt over total assets at year-end; |

| REC_INV | = | the ratio of the sum of receivables and inventories to total assets at year-end; |

| ZSCORE | = | Altman’s bankruptcy score: 3.3 × Net income/Total Assets + 0.99 × Sales/Total Assets + 1.4 × Retained earnings/Total Assets + 1.2 × Working capital/Total Assets + 0.6 × Market value of equity/Total liabilities; |

| TENURELAG | = | the natural logarithm of auditor tenure plus one in the previous year; |

| SPECIALIST | = | 1 if an audit firm has the largest market share in a particular industry and its market share is at least 10 percent greater compared to the second-largest market share, and 0 otherwise; |

| CI_FEE | = | the audit fees of a client divided by the sum of total audit fees of all clients audited by a given auditor in a particular year; |

| DELAY | = | the natural logarithm of the number of days between the year-end and the audit signature date; |

| LISTINGAGE | = | number of years that firms have been listed on the stock exchange; |

| DELIST | = | 1 if a firm is delisted, and 0 otherwise; |

| IND_BOARD | = | the percentage of independent board members to the total numbers of board of directors; |

| FOREIGN | = | the percentage of foreign-based sales; |

| SQSEG | = | the square root of the total number of segments. |

| Audit Quality Model (3) | ||

| DA | = | performance-matched discretionary accruals; |

| FSD_SCORE | = | financial statement divergence score (Amiram et al., 2015) multiplied by 100; |

| LAH | = | the natural logarithm of audit hours; |

| EST_AGE | = | number of years that firms have been established; |

| IND_GROWTH | = | the annual percentage change in total industry sales by the two-digit SIC code; |

| TENURE | = | the number of consecutive years that the same audit firm audited the company. |

| Voluntary Auditor Selection Model in the Post-Mandate Period (4) | ||

| VOL_SWITCH | = | 1 if a firm voluntarily switches auditors during the post-mandate period when auditor choice is discretionary, and 0 otherwise; |

| CASH | = | cash plus cash equivalents scaled by total assets; |

| GROWTH | = | the annual percentage change in total assets; |

| ACQUIRE | = | 1 if cash outflows related to acquisitions or the contribution of acquisitions to sales exceed ten percent of total assets, and 0 otherwise; |

| CFEARLY | = | 1 if the company is in the introduction or growth stage of its life cycle, and 0 otherwise; |

| CFMATURE | = | 1 if the company is in the introduction or growth stage of its life cycle, and 0 otherwise; |

| MODOPIN | = | 1 if firms report a nonstandard audit opinion, and 0 otherwise; |

| SHORT_TEN | = | 1 if auditor tenure with the company is three years or less, and 0 otherwise. |

References

- Alhazmi, A. H. J., Islam, S., & Prokofieva, M. (2024). The impact of changing external auditors, auditor tenure, and audit firm type on the quality of financial reports on the Saudi stock exchange. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(9), 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, K., Eshleman, D., & Guo, P. (2021). Investor sentiment and audit opinion shopping. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 40, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiram, D., Bozanic, Z., & Rouen, E. (2015). Financial statement errors: Evidence from the distributional properties of financial statement numbers. Review of Accounting Studies, 20(4), 1540–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, R. (1982). The auditor as an economic agent. Journal of Accounting Research, 20(2), 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrunada, A., & Paz-Ares, C. (1997). Mandatory rotation of company auditors. International Review of Law and Economics, 17, 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, D. R., Neal, T. L., Reid, L. C., & Shipman, J. E. (2019). Auditing goodwill in the post-amortization era: Challenges for auditors. Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(1), 82–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G., Rho, J., & Ro, B. (2007). The effect of mandatory audit firm retention on audit quality: Evidence from the Korean audit market [Unpublished Working paper]. Purdue University.

- Bartov, E., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. S. (2000). Discretionary-accruals models and audit qualifications. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 30(3), 421–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, N. R., Draeger, M., & Sterin, M. (2022). Management’s undue influence over audit committee members: Evidence from auditor reporting and opinion shopping. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 41(1), 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, J. P., Khurana, I. K., & Raman, K. K. (2008). Audit firm tenure and the equity risk premium. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 23(1), 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. V., & Knechel, W. R. (2016). Auditor–client compatibility and audit firm selection. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(3), 725–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameran, M., Francis, J. R., Marra, A., & Pettinicchio, A. (2015). Are there adverse consequences of mandatory auditor rotation? evidence from the italian experience. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cameran, M., Prencipe, A., & Trombetta, M. (2016). Mandatory audit firm rotation and audit quality. European Accounting Review, 25(1), 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcello, J. V., & Nagy, A. L. (2004). Audit firm tenure and fraudulent financial reporting. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 23(2), 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcello, J. V., & Neal, T. L. (2003). Audit committee characteristics and auditor dismissals following “new” going-concern reports. The Accounting Review, 78(1), 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, P., & Simnett, R. (2006). Audit partner tenure and audit quality. The Accounting Review, 81(3), 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casterella, J. R., & Johnston, D. (2013). Can the academic literature contribute to the debate over mandatory audit firm rotation? Research in Accounting Regulation, 25(1), 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanach, A. H., Jr., & Walker, P. L. (1999). The international debate over mandatory auditor rotation: A conceptual research framework. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 8(1), 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. J., & Hong, J. (2000). Economic performance of group-affiliated companies in Korea: Intergroup resource sharing and internal business transactions. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Francis, J. R., & Hou, Y. (2019). Opinion shopping through same-firm audit office switches. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2899888 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Chen, F., Peng, S., Xue, S., Yang, Z., & Ye, F. (2016). Do audit clients successfully engage in opinion shopping? Partner-level evidence. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(1), 79–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W., Lisic, L. L., Long, X., & Wang, K. (2013). Do regulations limiting management influence over auditors improve audit quality? Evidence from China. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 32(2), 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P., Wu, D., Xue, J., & Yau, L. N. B. (2025). Are all auditors the same? KAM topic selection and audit procedure choices in the United Kingdom. Journal of International Accounting Research, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. U., Na, H. J., & Lee, K. C. (2023). Does explanatory language convey the auditor’s perceived audit risk? A study using a novel big data analysis metric. Managerial Auditing Journal, 38(6), 783–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C. W., & Rice, S. J. (1982). Qualified audit opinions and auditor switching. The Accounting Review, 57, 326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H., Jo, J., & Sonu, C. H. (2025). Pricing opinion shopping: Evidence from an emerging debt market. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 61(13), 3989–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H., Kim, Y., & Sunwoo, H. (2021). Korean evidence on auditor switching for opinion shopping and capital market perceptions of audit quality. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics, 28(1), 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H., & Lee, E. Y. (2024). Does opinion shopping impair auditor independence? Evidence from tax avoidance. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 20(1), 100398. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H., Sonu, C. H., Zang, Y., & Choi, J. (2019). Opinion shopping to avoid a going concern audit opinion and subsequent audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 38(2), 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Corbella, S., Florio, C., Gotti, G., & Mastrolia, S. A. (2015). Audit firm rotation, audit fees and audit quality: The experience of Italian public companies. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 25, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowle, E. N., Decker, R. P., & Rowe, S. P. (2023). Retain or rotate: The association between frequent auditor switching and audit quality. Accounting Horizons, 37(3), 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerney, K., Schmidt, J., & Thompson, A. M. (2014). Does auditor explanatory language in unqualified audit reports indicate increased financial misstatement risk? The Accounting Review, 89(6), 2115–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerney, K., Schmidt, J., & Thompson, A. M. (2019). Do investors respond to explanatory language included in unqualified audit reports? Contemporary Accounting Research, 36, 198–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, B. W., & Booker, Q. (2011). The effects of audit firm rotation on perceived auditor independence and audit quality. Research in Accounting Regulation, 23(1), 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L. R., Soo, B. S., & Trompeter, G. M. (2009). Auditor tenure and the ability to meet or beat earnings forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(2), 517–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayanandan, A., & Kuntluru, S. (2023). Mandatory auditor rotation and audit quality. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management, 31(4), 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, L. (1981). Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M. L., & Francis, J. R. (2005). Audit research after Sarbanes-Oxley. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 24(s-1), 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M. L., & Subramanyam, K. R. (1998). Auditor changes and discretionary accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25(1), 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M. L., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting Economics, 58(2–3), 275–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M. L., Zhang, J., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Do managers successfully shop for auditors who allow them to opportunistically report positive news? Evidence from accounting estimates. Management Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, B., Hijink, S., & Veld, L. I. (2020). Mandatory Audit firm rotation for listed companies: The effects in the Netherlands. European Business Organization Law Review (EBOR), 21(4), 937–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M., Li, J., Simunic, D. A., & Zhou, N. (2019). Audit retendering and mandatory auditor rotation [Unpublished Working paper]. Baruch College Zicklin School of Business.

- de Ricquebourg, A. D., & Maroun, W. (2023). How do auditor rotations affect key audit matters? Archival evidence from South African audits. The British Accounting Review, 55(2), 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X., Xiao, L., & Du, Y. (2023). Does CEO–auditor dialect connectedness trigger audit opinion shopping? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 184(2), 391–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, R. A. (1993). Auditing standards, legal liability, and auditor wealth. Journal of Political Economy, 101(5), 887–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ege, M. S., & Stuber, S. B. (2022). Are auditors rewarded for low audit quality? The case of auditor lenience in the insurance industry. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 73(1), 101424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M., Elshandidy, T., & Ahmed, Y. (2023). Is expanded auditor reporting meaningful? UK evidence. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 53, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament & European Council. (2014a). Directive 2014/56/EU of the European parliament and of the council of 16 April 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/56/oj/eng (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- European Parliament & European Council. (2014b). Regulation (E.U.) no. 537/2014 of the European parliament and of the council 16 April 2014 on specific requirements regarding statutory audit of public-interest entities and repealing commission decision 2005/909/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014R0537 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Financial Supervisory Service. (1997–2009). Public notice on analysis of auditor opinion and explanatory language in audit reports in listing companies. Available online: https://www.fss.or.kr/fss/bbs/B0000154/list.do?menuNo=200467&bbsId=&cl1Cd=&pageIndex=42&sdate=&edate=&searchCnd=1&searchWrd= (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Financial Supervisory Service. (2008). Public notice on amendments of mandatory audit firm rotation in the external audit Act. No. 2008–70. Available online: https://www.moleg.go.kr/lawinfo/makingInfo.mo?mid=a1010401000-0&lawSeq=7421&lawCd=200000013690&lawType=TYPE5¤tPage=2&keyField=lmNm&keyWord=%EC%99%B8%EB%B6%2580%EA%B0%90%EC%82%AC&stFmt=&edYdFmt=&lsClsCd=&cptOfiOrgCd= (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Financial Supervisory Service. (2014). Guide to interpreting corporate disclosures in Korea. Available online: https://www.fss.or.kr/fss/bbs/B0000188/view.do?nttId=11023&menuNo=200218 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Firth, M., Rui, O. M., & Wu, W. (2011). Cooking the books: Recipes and costs of falsified financial statements in China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(2), 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florio, C. (2024). A structured literature review of empirical research on mandatory auditor rotation. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 55, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, R., Khemakhem, H., & Herda, D. N. (2016). Audit committee perspectives on mandatory audit firm rotation: Evidence from Canada. Journal of Management and Governance, 20(3), 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, M., & Raghunandan, K. (2002). Auditor tenure and audit reporting failures. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 21(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, P. A., & Lont, D. H. (2010). Do investors care about auditor dismissals and resignations? What drives the response? Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 29(2), 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. K., Mortal, S., Chakrabarty, B., Guo, X., & Turban, D. B. (2020). CFO gender and financial statement irregularities. The Academy of Management Journal, 63(3), 802–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A., Bhuiyan, B. U., Huang, H. J., & Miah, M. S. (2019a). Determinants of audit report lag: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Auditing, 23(1), 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A., Wu, J., Bhuiyan, B. U., & Sun, X. (2019b). Determinants of auditor choice: Review of the empirical literature. International Journal of Auditing, 23(2), 308–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harber, M., Marx, B., & De Jager, P. (2020). The perceived financial effects of mandatory audit firm rotation. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting, 31(2), 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herald Business Newspaper. (2002). Hyundai motors’ union demands auditor switching. Available online: https://urisaju.net/board/view.php?id=sub31&uniq=236&p=432&c1=0&c2=0&c3=0&c4=0&c5=0&opt=&key=&d1=&d2= (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Horton, J., Livne, G., & Pettinicchio, A. (2020). Empirical evidence on audit quality under a dual mandatory auditor rotation rule. European Accounting Review, 30(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J. O., Rosser, D. M., & Rowe, S. P. (2021). Using machine learning to predict auditor switches: How the likelihood of switching affects audit quality among non-switching clients. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 40(5), 106785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A. B., Moldrich, M., & Roebuck, P. (2008). Mandatory audit firm rotation and audit quality. Managerial Auditing Journal, 23(5), 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadiyappa, N., Hickman, L. E., Kakani, R. K., & Abidi, Q. (2021). Auditor tenure and audit quality: An investigation of moderating factors prior to the commencement of mandatory rotations in India. Managerial Auditing Journal, 36(5), 724–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D., & Velury, U. (2008). Does auditor tenure influence the reporting of conservative earnings? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 27(2), 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E., Khurana, I. K., & Reynolds, J. K. (2002). Audit-firm tenure and the quality of financial reports. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(4), 637–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalanjati, D. S., Nasution, D., Jonnergård, K., & Sutedjo, S. (2019). Auditor rotations and audit quality: A perspective from cumulative number of audit partner and audit firm rotations. Asian Review of Accounting, 27(4), 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, K. A., Wan Ismail, W. A., & Ariff, A. M. (2022). Auditor tenure, investor protection and accounting quality: International evidence. Accounting Research Journal, 35(2), 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. M., Kim, S. M., Lee, D. H., & Yoo, S. W. (2019). How investors perceive mandatory audit firm rotation in Korea. Sustainability, 11(4), 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klevak, J., Livnat, J., Pei, D., & Suslava, K. (2023). Critical audit matters: Possible market misinterpretation. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 42(3), 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Knechel, W. R., & Vanstraelen, A. (2007). The relationship between auditor tenure and audit quality implied by going concern opinions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 26(1), 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Economic Daily. (1996). South Korea’s watchdog urges proactive use of explanatory language in audit reports. Available online: https://www.kinds.or.kr/v2/news/newsDetailView.do?newsId=02100601.20160116011400872 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Korea Economic Daily. (2008). Big 4 auditors are facing a cutthroat competition to obtain new clients. Available online: https://m.news.nate.com/view/20080121n23294 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Kothari, S. P. (2001). Capital markets research in accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31(1–3), 105–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraakman, R. H. (1986). Gatekeepers: The anatomy of a third-party enforcement strategy. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 2(1), 53–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. Y., Lim, Y., & Simnett, R. (2014). The effect of mandatory audit firm rotation on audit quality and audit fees: Empirical evidence from the korean audit market. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 33(4), 167–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B., Gamble, G., Noland, T., & Zhao, Y. (2024). The effects of regulated auditor tenure on opinion shopping: Evidence from the Korean market. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(11), 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, C. (1998). Audit quality and auditor switching: Some lessons for policy makers [Working paper]. Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=121048 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Lennox, C. (2000). Do companies successfully engage in opinion-shopping? The UK experience. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 29(3), 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, C. (2002). Opinion shopping, audit firm dismissals, and audit committees [Working Paper]. Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=299843 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Lennox, C. (2014). Auditor tenure and rotation. In The Routledge companion to auditing (pp. 111–128). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lennox, C., Wu, X., & Zhang, T. (2014). Does mandatory rotation of audit partners improve audit quality? The Accounting Review, 89(5), 1775–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y. (2025). The effect of mandatory audit firm rotation on firm value: Evidence from Korea. Journal of International Accounting Research, 24(2), 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. (2006). Does opinion shopping impair auditor independence and audit quality? Journal of Accounting Research, 44(3), 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T., & Sivaramakrishnan, K. (2009). Mandatory audit firm rotation: Fresh look versus poor knowledge. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 28(2), 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, D., & Lim, H. (2018). Conservative reporting and the incremental effect of mandatory audit firm rotation policy: A comparative analysis of audit partner rotation vs audit firm rotation in South Korea. Australian Accounting Review, 28(3), 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minichilli, A., Prencipe, A., Radhakrishnan, S., & Siciliano, G. (2022). What’s in a name? Eponymous private firms and financial reporting quality. Management Science, 68(3), 2330–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, H. (2021). Dressing for the occasion? Audit quality in the presence of competition for new clients. The Accounting Review, 96(6), 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustikarini, A., & Adhariani, D. (2022). In auditor we trust: 44 years of research on the auditor-client relationship and future research directions. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(2), 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J. N., Myers, L. A., & Omer, T. C. (2003). Exploring the term of the auditor-client relationship and the quality of earnings: A case for mandatory auditor rotation? The Accounting Review, 78(3), 779–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, N. J., Persellin, J. S., Wang, D., & Wilkins, M. S. (2016). Internal control opinion shopping and audit market competition. The Accounting Review, 91(2), 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osma, B. G., Noguer, B. G., Cristóbal, E. D. L. H., & Rusanescu, S. (2022). Opinion-shopping: Firm versus partner-level evidence. Accounting and Business Research, 52(7), 773–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). (2011). Concept release on auditor in-dependence and audit firm rotation, pcaob release no. 2011-006, August 16, 2011. PCAOB. Available online: https://pcaobus.org/about/rules-rulemaking/rulemaking-dockets/docket-037-concept-release-on-auditor-independence-and-audit-firm-rotation (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Quick, R., Toledano, D. S., & Toledano, J. S. (2024). Measures for enhancing auditor independence: Perceptions of spanish non-professional investors and auditors. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 30(2), 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, L. C., & Carcello, J. V. (2017). Investor reaction to the prospect of mandatory audit firm rotation. The Accounting Review, 92(1), 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Barbadillo, E., Gómez-Aguilar, N., & Biedma-López, E. (2006). Long-term audit engagements and opinion shopping: Spanish evidence. Accounting Forum, 30(1), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Barbadillo, E., Gómez-Aguilar, N., & Carrera, N. (2009). Does mandatory audit firm rotation enhance auditor independence? Evidence from Spain. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 28(1), 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, M., Zimon, G., Tarighi, H., & Gholamzadeh, J. (2022). The effect of mandatory audit firm rotation on earnings management and audit fees: Evidence from Iran. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(3), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, Z., & Zhang, J. (2022). Do companies try to conceal financial misstatements through auditor shopping? Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 49(1–2), 140–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyi, P., Raghunandan, K., & Barua, A. (2010). Audit report lags after voluntary and involuntary auditor changes. Accounting Horizons, 24(4), 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstraelen, A. (2000). Impact of renewable long-term audit mandates on audit quality. European Accounting Review, 9(3), 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. (2023). Determinants and financial consequences of environmental performance and reporting: A literature review of European archival research. Journal of Environmental Management, 340, 117916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velte, P., & Loy, T. (2018). The impact of auditor rotation, audit firm rotation and non-audit services on earnings quality, audit quality and investor perceptions: A literature review. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 7(2), 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Zhang, L., Ma, Q., & Wu, C. (2024). The impact of financial risk on boilerplate of key audit matters: Evidence from China. Research in International Business and Finance, 70, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R. L., & Zimmerman, J. L. (1983). Agency problems, auditing, and the theory of the firm: Some evidence. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(3), 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C., Yuwen, H., & Yang, D. (2023). Goodwill impairment, auditor dismissal and opinion shopping–evidence from China. China Journal of Accounting Studies, 11(4), 864–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y., & Xue, S. (2019). Comment letters and internal control opinion shopping. China Journal of Accounting Studies, 7(2), 214–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G., Chen, S., Zhang, P., & Lin, X. (2022). Does the random inspection reduce audit opinion shopping? China Journal of Accounting Studies, 10(4), 528–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. (1999). A bargaining model of auditor reporting. Contemporary Accounting Research, 16, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Selection Criteria | Number of Firm-Years |

|---|---|

| Number of KOSPI- and KOSDAQ-listed firms | 20,843 |

| Less: non-December fiscal year-end firms | 1646 |

| Less: firms in non-compliance with mandatory rotation or retention | 755 |

| Less: firms in the financial and insurance industries | 350 |

| Less: firms that changed their fiscal year-end | 45 |

| Less: firms missing relevant data | 7262 |

| Both mandatory and voluntary sample for models (1) and (2) | 10,785 |

| Less: voluntary auditor switching and retention | 3329 |

| Mandatory sample for models (3) and (4) | 7456 |

| Less: firms missing relevant data | 6422 |

| Post-mandate sample for model (5) | 1034 |

| (1) Voluntary Auditor Switching and Retention | (2) Mandatory Auditor Switching and Retention | (3) Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinions | # of Obs. | % | # of Obs. | % | # of Obs. | % |

| Unqualified opinions with no explanatory language | 696 | 20.68 | 2058 | 27.6 | 2754 | 25.54 |

| Unqualified opinions with harmless explanatory language | 304 | 9.11 | 688 | 9.23 | 992 | 9.2 |

| Unqualified opinions with potentially negative explanatory language | 405 | 12.14 | 663 | 8.89 | 1068 | 9.9 |

| Unqualified opinions with harmful explanatory language | 1872 | 56.12 | 3919 | 52.56 | 5791 | 53.69 |

| Qualified opinions | 38 | 1.14 | 71 | 0.95 | 102 | 0.95 |

| Adverse opinions | 1 | 0.03 | 2 | 0.03 | 3 | 0.03 |

| Opinion disclaimer | 20 | 0.6 | 55 | 0.74 | 75 | 0.7 |

| Total | 3336 | 100 | 7456 | 100 | 10,785 | 100 |

| Dep. = | MO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |||

| Variable | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat |

| MOLAG | 2.034 *** | 49.35 | 1.904 *** | 26.88 |

| SIZE | 0.099 *** | 5.71 | 0.091 *** | 3.10 |

| LEV | 0.484 *** | 4.06 | 0.598 *** | 2.73 |

| LIQ | 0.005 | 0.69 | 0.012 | 0.94 |

| LOSS | 0.062 | 1.20 | 0.057 | 0.63 |

| BM | 13.452 ** | 2.37 | 31.440 *** | 2.64 |

| ISSUANCE | −0.022 | −0.61 | −0.006 | −0.09 |

| OCF | −0.322 ** | −2.03 | −0.228 | −0.80 |

| BIGN | −0.628 *** | −16.69 | −0.433 *** | −6.46 |

| RETURN | 0.009 | 0.43 | 0.037 | 1.14 |

| VOLATILITY | 0.121 | 1.11 | −0.027 | −0.16 |

| PROF | −0.988 *** | −7.59 | −0.865 *** | −3.68 |

| S | 0.526 | 0.64 | 1.450 | 1.44 |

| S × MOLAG | −0.719 *** | −7.81 | −0.470 *** | −3.59 |

| S × SIZE | −0.009 | −0.22 | −0.047 | −0.88 |

| S × LEV | 0.096 | 0.35 | −0.096 | −0.27 |

| S × LIQ | −0.020 | −1.07 | −0.024 | −0.97 |

| S × LOSS | −0.025 | −0.21 | 0.119 | 0.70 |

| S × BM | −7.273 | −0.75 | −22.760 | −1.53 |

| S × ISSUANCE | −0.073 | −0.80 | −0.043 | −0.34 |

| S × OCF | −0.892 ** | −2.50 | −1.399 *** | −2.84 |

| S × BIGN | −0.139 | −1.46 | −0.085 | −0.64 |

| S × RETURN | 0.077 ** | 2.09 | 0.036 | 0.81 |

| S × VOLATILITY | 0.289 | 1.24 | 0.061 | 0.33 |

| S × PROF | 0.604 ** | 2.31 | 0.995 *** | 3.05 |

| MAND | −0.034 | −0.05 | ||

| MAND × MOLAG | 0.179 ** | 2.30 | ||

| MAND × SIZE | 0.010 | 0.30 | ||

| MAND × LEV | −0.148 | −0.57 | ||

| MAND × LIQ | −0.008 | −0.49 | ||

| MAND × LOSS | 0.003 | 0.03 | ||

| MAND × BM | −25.183 ** | −2.01 | ||

| MAND × ISSUANCE | −0.030 | −0.38 | ||

| MAND × OCF | −0.140 | −0.41 | ||

| MAND × BIGN | −0.270 *** | −3.36 | ||

| MAND × RETURN | −0.038 | −1.04 | ||

| MAND × VOLATILITY | 0.250 | 1.11 | ||

| MAND × PROF | −0.144 | −0.50 | ||

| S × MAND | −3.506 ** | −2.01 | ||

| S × MAND × MOLAG | −0.506 ** | −2.56 | ||

| S × MAND × SIZE | 0.171 * | 1.90 | ||

| S × MAND × LEV | 0.493 | 0.77 | ||

| S × MAND × LIQ | 0.003 | 0.06 | ||

| S × MAND × LOSS | −0.247 | −0.93 | ||

| S × MAND × BM | −12.902 | −0.37 | ||

| S × MAND × ISSUANCE | −0.152 | −0.76 | ||

| S × MAND × OCF | 1.443 * | 1.80 | ||

| S × MAND × BIGN | −0.600 *** | −2.70 | ||

| S × MAND × RETURN | −0.024 | −0.24 | ||

| S × MAND × VOLATILITY | 0.576 | 1.27 | ||

| S × MAND × PROF | −1.021 | −1.42 | ||

| Intercept | −3.141 *** | −7.49 | −3.105 *** | −5.04 |

| Industry Effects | YES | YES | ||

| Year Effects | YES | YES | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.459 | 0.465 | ||

| Observations | 10,785 | 10,785 | ||

| Panel A: Observed Mandatory Rotation or Retention to Predicted Preference | |||

| Predicted | |||

| Observed | Switching Preferred (S = 1) | Retention Preferred (S = 0) | Total |

| Mandatory Rotation (MAND = 1 & S = 1) | 180 | 314 | 494 |

| Mandatory Retention (MAND = 1 & S = 0) | 2932 | 4030 | 6962 |

| Total | 3112 | 4344 | 7456 |

| Panel B: Identification of Disguised Opinion Shopping | |||

| Aligned = | 180 + 4030 = | 4210 | 56.5% |

| Misaligned = | 314 + 2932 = | 3246 | 43.5% |

| Total = | 7456 | 100% | |

| (1) Mandatory Rotation Sample | (2) Mandatory Retention Sample | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean in DOS = 0 | Mean in DOS = 1 | Diff. in Means | t-Stat | p-Value | Mean in DOS = 0 | Mean in DOS = 1 | Diff. in Means | t-Stat | p-Value | |

| Dependent Variables | ||||||||||

| MO | 0.32 | 0.59 | −0.27 | −6.1 *** | (0.00) | 0.84 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 48.87 *** | (0.00) |

| DA | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 4.58 *** | (0.00) | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −16.2 *** | (0.00) |

| FSD_SCORE | 3.55 | 3.29 | 0.26 | 2.42 ** | (0.02) | 3.42 | 3.54 | −0.12 | −4.21 *** | (0.00) |

| VOL_SWITCH | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.06 | 1.28 | (0.20) | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 4.08 *** | (0.00) |

| Independent Variables | ||||||||||

| MOLAG | 0.21 | 0.91 | −0.70 | −22 *** | (0.00) | 0.95 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 83.5 *** | (0.00) |

| SIZE | 18.63 | 18.56 | 0.08 | 0.68 | (0.50) | 18.84 | 18.27 | 0.57 | 15.54 *** | (0.00) |

| LIQ | 2.50 | 2.09 | 0.41 | 1.53 | (0.13) | 2.34 | 2.58 | −0.24 | −3.25 *** | (0.00) |

| DE | 0.10 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −2.1 ** | (0.03) | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 14.60 *** | (0.00) |

| REC_INV | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 1.04 | (0.30) | 0.27 | 0.30 | −0.03 | −6.90 *** | (0.00) |

| ISSUANCE | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 0.18 | (0.85) | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 5.29 *** | (0.00) |

| ZSCORE | 3.02 | 1.49 | 1.53 | 3.99 *** | (0.00) | 2.39 | 3.51 | −1.12 | −11.2 *** | (0.00) |

| TENURELAG | 3.16 | 3.13 | 0.02 | 0.72 | (0.47) | 2.09 | 2.05 | 0.04 | 1.99 ** | (0.05) |

| BIGN | 0.46 | 0.47 | −0.00 | −0.04 | (0.97) | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 4.57 *** | (0.00) |

| SPECIALIST | 0.04 | 0.10 | −0.06 | −2.3 ** | (0.02) | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 8.69 *** | (0.00) |

| CI_FEE | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.00 | −0.05 | (0.96) | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −4.28 *** | (0.00) |

| DELAY | 3.91 | 3.96 | −0.05 | −1.59 | (0.11) | 3.80 | 3.88 | −0.08 | −9.86 *** | (0.00) |

| LISTINGAGE | 13.97 | 13.78 | 0.19 | 0.25 | (0.80) | 13.34 | 11.02 | 2.31 | 10.19 *** | (0.00) |

| DELIST | 0.12 | 0.26 | −0.14 | −3.6 *** | (0.00) | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 1.49 | (0.14) |

| RETURN | −0.16 | −0.34 | 0.18 | 2.77 *** | (0.01) | 0.12 | 0.30 | −0.17 | −7.25 *** | (0.00) |

| VOLATILITY | 0.68 | 0.71 | −0.03 | −1.56 | (0.12) | 0.63 | 0.66 | −0.04 | −3.29 *** | (0.00) |

| INDBOARD | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.58 | (0.56) | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 5.42 *** | (0.00) |

| FOREIGN | 0.23 | 0.33 | −0.10 | −3.2 *** | (0.00) | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 5.58 *** | (0.00) |

| SQSEG | 1.49 | 1.53 | −0.04 | −0.96 | (0.34) | 1.49 | 1.46 | 0.03 | 3.07 *** | (0.00) |

| LAH | 6.55 | 6.53 | 0.01 | 0.25 | (0.80) | 6.43 | 6.27 | 0.15 | 5.97 *** | (0.00) |

| EST_AGE | 28.21 | 28.31 | −0.10 | −0.08 | (0.93) | 27.66 | 24.45 | 3.21 | 9.09 *** | (0.00) |

| OCF | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −3.6 *** | (0.00) | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 14.08 *** | (0.00) |

| IND_GROWTH | 0.15 | 0.17 | −0.02 | −1.72 * | (0.09) | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 1.01 | (0.31) |

| LEV | 0.41 | 0.52 | −0.11 | −4.1 *** | (0.00) | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.10 | 17.12 *** | (0.00) |

| TENURE | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.27 | 5.03 | 0.24 | 2.56 ** | (0.01) | |||

| CASH | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 2.16 ** | (0.03) | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −4.09 *** | (0.00) |

| PROF | −0.01 | −0.22 | 0.21 | 4.73 *** | (0.00) | −0.10 | 0.00 | −0.10 | −12.5 *** | (0.00) |

| LOSS | 0.32 | 0.42 | −0.10 | −2.2 ** | (0.03) | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.90 | (0.37) |

| GROWTH | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 1.95 * | (0.05) | 0.05 | 0.15 | −0.10 | −11.7 *** | (0.00) |

| ACQUIRE | 0.08 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −1.04 | (0.30) | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 4.89 *** | (0.00) |

| CFEARLY | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 1.41 | (0.16) | 0.36 | 0.45 | −0.09 | −6.77 *** | (0.00) |

| CFMATURE | 0.26 | 0.37 | −0.11 | −2.2 ** | (0.03) | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 9.56 *** | (0.00) |

| MODOPIN | 0.87 | 0.92 | −0.04 | −1.55 | (0.12) | 0.91 | 0.57 | 0.34 | 36.70 *** | (0.00) |

| SHORT_TEN | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.46 | 0.48 | −0.02 | −1.56 | (0.12) | |||

| N | 314 | 180 | 2932 | 4030 | ||||||

| Full Mandate Sample | Mandatory Rotation | Mandatory Retention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||

| Dep. = | MO | MO | MO | MO | ||||

| Variable | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat |

| DOS | −0.254 *** | −4.82 | −0.070 | −0.29 | −0.214 *** | −3.40 | ||

| DOS_SWITCH | −0.675 *** | −4.32 | ||||||

| DOS_RETAIN | −0.157 ** | −2.47 | ||||||

| MOLAG | 1.889 *** | 36.30 | 1.971 *** | 31.51 | 1.272 *** | 5.47 | 1.982 *** | 32.98 |

| S | −0.335 *** | −3.32 | −0.095 | −0.73 | ||||

| SIZE | 0.063 ** | 2.43 | 0.069 *** | 2.64 | 0.232 ** | 2.51 | 0.037 | 1.59 |

| LIQ | −0.001 | −0.11 | 0.001 | 0.14 | −0.045 | −1.36 | 0.007 | 0.66 |

| DE | 0.314 | 1.59 | 0.322 | 1.64 | 0.807 | 0.85 | 0.476 ** | 2.55 |

| REC_INV | −0.131 | −0.92 | −0.151 | −1.05 | −0.971 * | −1.75 | 0.122 | 0.84 |

| ISSUANCE | −0.038 | −0.92 | −0.038 | −0.91 | −0.176 | −1.07 | −0.048 | −1.16 |

| ZSCORE | −0.038 *** | −4.44 | −0.039 *** | −4.55 | −0.031 | −0.97 | −0.044 *** | −5.07 |

| TENURELAG | 0.057 ** | 2.12 | 0.058 ** | 2.17 | −0.157 | −0.74 | 0.135 *** | 5.29 |

| BIGN | −0.772 *** | −15.30 | −0.754 *** | −14.95 | −1.656 *** | −7.88 | −0.609 *** | −12.20 |

| SPECIALIST | 0.023 | 0.38 | 0.027 | 0.44 | 0.345 | 1.08 | −0.006 | −0.10 |

| CI_FEE | −0.057 | −0.36 | −0.063 | −0.39 | −0.434 | −0.52 | −0.031 | −0.19 |

| DELAY | 0.095 | 1.44 | 0.098 | 1.49 | 0.396 | 1.36 | −0.110 * | −1.71 |

| LISTINGAGE | −0.003 | −1.11 | −0.003 | −1.16 | −0.017 | −1.48 | −0.004 * | −1.74 |

| DELIST | 0.161 *** | 2.66 | 0.169 *** | 2.76 | 0.387 | 1.64 | 0.166 *** | 2.86 |

| RETURN | −0.009 | −0.38 | −0.014 | −0.61 | −0.071 | −0.69 | −0.056 ** | −2.37 |

| VOLATILITY | 0.600 ** | 2.51 | 0.591 ** | 2.48 | 1.283 *** | 2.79 | 0.673 *** | 2.88 |

| INDBOARD | −0.053 | −0.35 | −0.068 | −0.44 | 0.399 | 0.65 | −0.400 *** | −2.66 |

| FOREIGN | 0.071 | 0.92 | 0.078 | 1.01 | 0.391 | 1.32 | 0.059 | 0.77 |

| SQSEG | 0.153 *** | 3.42 | 0.152 *** | 3.39 | 0.181 | 1.07 | 0.131 *** | 2.92 |

| Intercept | −2.605 *** | −3.32 | −2.842 *** | −3.60 | −6.738 *** | −2.98 | −1.072 | −1.46 |

| Industry Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||

| Year Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.491 | 0.492 | 0.408 | 0.473 | ||||

| Observations | 7456 | 7456 | 494 | 6962 | ||||

| Full Mandate Sample | Mandatory Rotation | Mandatory Retention | Full Mandate Sample | Mandatory Rotation | Mandatory Retention | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |||||||||

| Dep.= | DA | DA | DA | DA | FSD_SCORE | FSD_SCORE | FSD_SCORE | FSD_SCORE | ||||||||

| Variable | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat |

| DOS | 0.044 *** | 10.26 | −0.029 | −1.09 | 0.056 *** | 13.12 | 0.101 *** | 3.31 | −0.044 | −0.36 | 0.119 *** | 3.67 | ||||

| DOS_SWITCH | −0.008 | −0.61 | −0.110 | −1.15 | ||||||||||||

| DOS_RETAIN | 0.047 *** | 10.84 | 0.113 *** | 3.65 | ||||||||||||

| LAH | −0.007 ** | −2.40 | −0.006 ** | −2.32 | 0.010 | 0.35 | −0.007 ** | −2.53 | 0.027 | 1.43 | 0.028 | 1.48 | −0.231 * | −1.79 | 0.032 * | 1.68 |

| SIZE | 0.019 *** | 9.42 | 0.019 *** | 9.41 | −0.000 | −0.03 | 0.020 *** | 10.04 | −0.047 *** | −3.18 | −0.047 *** | −3.14 | 0.021 | 0.30 | −0.045 *** | −2.99 |

| BIGN | 0.000 | 0.02 | −0.000 | −0.04 | 0.022 | 0.78 | 0.001 | 0.17 | −0.146 *** | −4.59 | −0.147 *** | −4.62 | −0.105 | −0.85 | −0.146 *** | −4.4 |

| EST_AGE | 0.000 ** | 2.17 | 0.000 ** | 2.37 | 0.000 | 0.43 | 0.000 ** | 2.31 | 0.001 | 0.71 | 0.001 | 0.83 | −0.006 | −1.27 | 0.001 | 0.98 |

| OCF | −0.676 *** | −46.49 | −0.670 *** | −45.88 | −0.890 *** | −9.33 | −0.652 *** | −45.99 | 0.367 *** | 2.87 | 0.393 *** | 3.06 | −0.089 | −0.18 | 0.415 *** | 3.1 |

| IND_GROWTH | 0.011 | 0.59 | 0.012 | 0.64 | 0.006 | 0.04 | 0.020 | 1.03 | −0.667 *** | −4.92 | −0.643 *** | −4.74 | −1.388 ** | −2.34 | −0.647 *** | −4.5 |

| LIQ | −0.001 | −1.47 | −0.001 | −1.28 | −0.003 | −0.72 | −0.001 | −0.79 | −0.001 | −0.25 | −0.001 | −0.14 | 0.040 * | 1.67 | −0.004 | −0.61 |

| LEV | −0.064 *** | −5.51 | −0.059 *** | −5.07 | −0.033 | −0.53 | −0.057 *** | −4.93 | −0.208 ** | −2.27 | −0.190 ** | −2.06 | −0.125 | −0.40 | −0.195 ** | −2.01 |

| TENURE | −0.000 | −0.05 | −0.000 | −0.55 | 0.000 | 0.26 | −0.011 *** | −2.98 | −0.013 *** | −3.35 | −0.012 *** | −3.16 | ||||

| Intercept | −0.314 *** | −9.01 | −0.319 *** | −9.16 | 0.017 | 0.07 | −0.336 *** | −10.09 | 4.409 *** | 18.13 | 4.380 *** | 18.00 | 4.991 *** | 4.82 | 4.311 *** | 17.55 |

| Industry Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||||

| Year Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||||

| Adj. R-squared | 0.288 | 0.290 | 0.318 | 0.312 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.200 | 0.039 | ||||||||

| Observations | 7456 | 7456 | 494 | 6962 | 7456 | 7456 | 494 | 6962 | ||||||||

| Full Mandate Sample | Mandatory Rotation | Mandatory Retention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||

| Dep. = | VOL_SWITCH | VOL_SWITCH | VOL_SWITCH | VOL_SWITCH | ||||

| Variable | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat |

| DOS | −0.343 *** | −3.31 | −0.147 | −0.94 | −0.611 *** | −3.42 | ||

| DOS_SWITCH | −0.233 | −1.59 | ||||||

| DOS_RETAIN | −0.440 *** | −3.23 | ||||||

| SIZE | −0.078 | −1.56 | −0.088 * | −1.73 | −0.117 | −1.38 | −0.051 | −0.70 |

| REC_INV | −0.336 | −0.87 | −0.339 | −0.88 | −0.440 | −0.79 | −0.154 | −0.25 |

| DA | 0.826 * | 1.75 | 0.927 * | 1.91 | −0.965 | −0.99 | 0.827 | 0.91 |

| CASH | −1.168 * | −1.70 | −1.137 * | −1.65 | −1.363 | −1.08 | −1.127 | −1.17 |

| PROF | −1.614 *** | −3.50 | −1.546 *** | −3.37 | −0.967 * | −1.78 | −3.249 *** | −3.08 |

| LOSS | 0.008 | 0.05 | 0.025 | 0.17 | −0.153 | −0.76 | −0.037 | −0.14 |

| GROWTH | −0.003 | −0.02 | −0.001 | −0.01 | 0.017 | 0.07 | −0.189 | −0.79 |

| ACQUIRE | −0.296 | −1.59 | −0.287 | −1.53 | −0.159 | −0.46 | −0.483 ** | −1.97 |

| CFEARLY | −0.192 | −1.40 | −0.181 | −1.31 | −0.302 | −1.60 | −0.013 | −0.05 |

| CFMATURE | 0.123 | 0.81 | 0.124 | 0.82 | 0.066 | 0.31 | 0.168 | 0.66 |

| MODOPIN | 0.200 | 1.57 | 0.165 | 1.25 | −0.098 | −0.47 | 0.485 ** | 2.45 |

| SPECIALIST | −0.097 | −0.59 | −0.100 | −0.61 | −0.479 | −1.40 | −0.095 | −0.43 |

| SHORT_TEN | −0.404 *** | −3.19 | −0.455 *** | −3.38 | −0.276 * | −1.67 | ||

| BIGN | −0.159 | −1.36 | −0.159 | −1.36 | −0.278 * | −1.67 | 0.155 | 0.76 |

| Intercept | 1.410 | 1.38 | 1.659 | 1.59 | 1.534 | 0.94 | 1.045 | 0.68 |

| Industry Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||

| Year Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.120 | 0.121 | 0.116 | 0.222 | ||||

| Observations | 1034 | 1034 | 445 | 589 | ||||

| Exclude Related Party Transactions | Include Potentially Negative Explanatory Language | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |||||||||

| Dep. = | DA | DA | FSD_SCORE | FSD_SCORE | DA | DA | FSD_SCORE | FSD_SCORE | ||||||||

| Variable | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat |

| DOS | 0.032 *** | 7.19 | 0.043 | 1.31 | 0.047 *** | 11.37 | 0.115 *** | 3.82 | ||||||||

| DOS_SWITCH | −0.001 | −0.14 | −0.037 | −0.51 | 0.003 | 0.21 | −0.053 | −0.57 | ||||||||

| DOS_RETAIN | 0.037 *** | 7.91 | 0.058 * | 1.66 | 0.050 *** | 11.83 | 0.125 *** | 4.10 | ||||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||||

| Industry Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||||

| Year Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||||

| Adj. R-squared | 0.283 | 0.284 | 0.037 | 0.038 | 0.291 | 0.292 | 0.040 | 0.040 | ||||||||

| Observations | 7456 | 7456 | 7456 | 7456 | 7456 | 7456 | 7456 | 7456 | ||||||||

| Apply 1% Cut-Off | Drop Observations Below 1% Cut-Off | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |||||||||

| Dep. = | DA | DA | FSD_SCORE | FSD_SCORE | DA | DA | FSD_SCORE | FSD_SCORE | ||||||||

| Variable | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat | Coeff | Z-Stat |

| DOS | 0.042 *** | 9.78 | 0.095 *** | 3.16 | 0.043 *** | 9.37 | 0.105 *** | 3.19 | ||||||||

| DOS_SWITCH | −0.015 | −1.09 | −0.066 | −0.68 | −0.010 | −0.72 | −0.048 | −0.49 | ||||||||

| DOS_RETAIN | 0.045 *** | 10.40 | 0.104 *** | 3.41 | 0.046 *** | 9.95 | 0.114 *** | 3.42 | ||||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||||

| Industry Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||||

| Year Effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||||

| Adj. R-squared | 0.287 | 0.289 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.315 | 0.317 | 0.040 | 0.040 | ||||||||

| Observations | 7456 | 7456 | 7456 | 7456 | 6213 | 6213 | 6213 | 6213 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, B. To Hide Behind the Mask of Mandates: Disguised Opinion Shopping Under Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation and Retention in Korea. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080410

Lee B. To Hide Behind the Mask of Mandates: Disguised Opinion Shopping Under Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation and Retention in Korea. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(8):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080410

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Beu. 2025. "To Hide Behind the Mask of Mandates: Disguised Opinion Shopping Under Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation and Retention in Korea" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 8: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080410

APA StyleLee, B. (2025). To Hide Behind the Mask of Mandates: Disguised Opinion Shopping Under Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation and Retention in Korea. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(8), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080410