Abstract

The study examined the mediating roles of adaptive leadership in the relationship between financial technology innovation and rural bank performance. A survey-based research approach was applied, and the hypotheses were tested using a sample of 305 respondents. A measurement model was employed to evaluate the validity and reliability of the scales used in the study. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to analyze the hypothesized relationships and test the mediation effects. The empirical findings support the hypothesized relationship between both financial technology innovation and the director’s individual performance on rural bank performance. Adaptive leadership was found not to mediate the association between financial technology innovation and rural bank performance. The research highlights the importance of financial technology innovation and individual director performance in enhancing rural bank performance. Furthermore, the findings support the notion that developing financial technology innovation is crucial for fostering adaptive leadership. Additionally, adaptive leadership contributes to strengthening director individual performance, which ultimately drives overall performance improvements in rural banks. The integration of these variables offers new empirical insights. It expands the understanding of rural bank performance, highlighting how internal capabilities can be optimized to improve organizational outcomes in this under-researched sector.

1. Introduction

In recent years, ASEAN’s fintech industry has shifted the spotlight toward emerging technologies and sustainability (PwC, 2024). According to Bank Indonesia’s regulations, the term ‘financial technology’, often abbreviated as fintech, refers to integrating technological advancements within the financial industry (Aldhi et al., 2024). Financial technology has transformed the financial services landscape, offering innovative solutions that cater to the diverse needs of individuals and businesses (Hudaefi, 2020). This transformative phenomenon, commonly known as “fintech”, has gained significant traction in emerging economies, where it has the potential to address the longstanding challenge of financial inclusion (Christiyanto et al., 2023; Mehrotra, 2019). Indonesia, as an emerging market, has witnessed the rapid growth of fintech, with the sector attracting significant investment and attention from both the public and private sectors (Rahmi, 2019).

According to Indonesian banking laws, banks are classified as either commercial or rural. Rural banks in Indonesia are commonly referred to as credit banks (Amanda, 2023). Rural banks hold a vital position in Indonesia’s financial system by advancing financial inclusion, especially for individuals, micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), cooperatives, and community-based institutions (Tedyono et al., 2025). One crucial aspect of the fintech landscape in Indonesia is its potential impact on rural banks, which play a vital role in providing financial services to underserved communities (Rahayu & Rahadi, 2023). As fintech continues to disrupt traditional banking models, it is essential to understand the role of leadership in fostering the adoption of fintech solutions within rural banks (Zhang & Lin, 2019). Indonesia, as one of the largest and most populous countries in Southeast Asia, has experienced a surge in fintech activity in recent years (Pambudianti et al., 2020) and the Indonesian government has recognized the importance of fintech in driving financial inclusion and taken steps to regulate and support the industry (Subagiyo, 2021).

The success of fintech adoption within rural banks is heavily dependent on the leadership of these institutions (Aulia et al., 2020). Effective leaders within rural banks must possess the vision, strategic acumen, and technological expertise to navigate the rapidly evolving fintech landscape (Yin, 2022). They must be able to identify and implement fintech solutions that cater to the unique needs of their rural clientele while also ensuring the long-term sustainability and competitiveness of their institutions (Goswami et al., 2022). In addition, rural bank leaders must be able to foster a culture of innovation and adaptability within their organizations (Sugiyanto & Setiawan, 2022). This requires a proactive approach to employee training, the development of digital capabilities, and the cultivation of partnerships with fintech providers (Linna, 2021). Furthermore, rural bank leaders must be able to navigate the regulatory landscape, collaborating with policymakers and regulators to ensure that the implementation of fintech solutions aligns with the overall financial inclusion agenda (Sahay et al., 2020). The existing body of research on the intersection of fintech and traditional banking provides valuable insights for rural banks as they navigate the transition to digital financial services (Hudaefi, 2020; Iman, 2018).

Studies have shown that the successful integration of fintech within conventional banking models requires a strategic and collaborative approach. Fintech firms and traditional banks must work together to leverage their respective strengths and create mutually beneficial partnerships (Yin, 2022). This model of cooperation can be particularly beneficial for rural banks, which may lack the resources and technical expertise to develop and implement fintech solutions independently (Zhang & Lin, 2019).

Research by Zhao et al. (2022) indicates that financial technology innovation influences bank performance. Financial technology represents a significant manifestation of innovation in the financial industry and has a profound impact on the banking sector (Iman, 2018). It helps alleviate information asymmetry issues arising from distance constraints and can reduce transaction costs (Alaassar et al., 2023). On the other hand, research by Thakor (2020) suggests that financial technology innovation can worsen bank performance because loan platforms and online investment opportunities may disrupt existing business models and potentially reduce the profitability of the banks involved.

Moreover, research has highlighted the importance of institutional leadership in driving the adoption of fintech within conventional banking. Leaders who are able to foster a culture of innovation, empower their teams, and effectively manage the risks associated with fintech integration are more likely to achieve successful outcomes (Frost, 2020; Gong, 2023; Unsal et al., 2020). Research by Wamburu et al. (2022) also demonstrates that adaptive leadership has a significant impact on organizational performance. As such, it is crucial for leaders to consider dimensions of adaptive leadership to gain perspective through reflection, identify challenges, and solve problems, thereby impacting organizational or company performance (Maulana et al., 2022). While the existing research provides valuable insights, it is essential to consider the unique context and challenges faced by rural banks in emerging economies, such as Indonesia (Anwar et al., 2019). A comparative analysis of fintech adoption in rural banks between Indonesia and other developing countries can offer valuable lessons and best practices (Harjanti et al., 2021; Rahmi, 2019).

In Indonesia, the adoption of fintech within rural banks has been influenced by a range of factors, including the regulatory environment, the availability of supporting infrastructure, and the level of digital literacy among rural populations (Mutiara et al., 2019). The Indonesian government has taken steps to encourage fintech innovation and promote financial inclusion, but more work is needed to ensure that rural banks are equipped to leverage these opportunities (Iman, 2018).

Developing countries, on the other hand, may have different challenges and approaches to fintech adoption in rural banking. For instance, studies have shown that the successful implementation of fintech in rural Kenya has been heavily dependent on the ability of financial technology firms to develop applications that are user-friendly and tailored to the needs of smallholder farmers (Wabwire, 2019). Similarly, research in India has highlighted the potential of fintech to improve the delivery of financial services to underserved communities, but also the need for regulatory support and capacity-building within traditional banking institutions (Mittal & Gupta, 2023).

By examining the experiences of fintech adoption in rural banks across different developing countries, rural bank leaders in Indonesia can learn from best practices, identify common challenges, and develop strategies to effectively harness the power of fintech to drive financial inclusion and sustainable development (Afif & Samsuri, 2022).

Leaders or superiors play a pivotal role in the success of a company, where the success of the company can be measured and seen through the performance it produces (Suwandi, 2021). Leaders or superiors, especially CEOs, hold the highest positions in a company and are responsible for the company’s stability (Sabir, 2017). They bear responsibilities including developing and implementing high-level strategies, making corporate decisions, managing overall company operations and resources, and serving as the primary link between the board and executive directors.

Research by Al-Matari (2019) indicates a positive and significant influence between several executive management characteristics, including director individual performance, on company performance. Executive management plays a role in assisting the achievement of company goals (Al-Matari, 2019) and research by Gupta and Mahakud (2020) shows that professional superiors can enhance performance with experienced superiors contributing to maximum performance, thereby influencing banking performance.

The existing research has highlighted the importance of leadership in driving the adoption of fintech within conventional banking. But there is a lack of in-depth understanding of the specific leadership factors that influence the impact of financial technology on the performance of rural banks (Agwu, 2021). The success of fintech integration in rural banks is heavily dependent on the ability of institutional leaders to navigate the complex and rapidly evolving fintech landscape (Goswami et al., 2022). Factors such as the leader’s vision, strategic acumen, technological expertise, and ability to foster a culture of innovation and adaptability within the organization can play a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of fintech implementation (Lee & Shin, 2018; Mirchandani et al., 2020).

This study is also supported by the resource-based view (RBV) theory, which emphasizes that an organization’s competitive advantage is primarily determined by its ability to manage internal resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (Wernerfelt, 1984). In today’s digital era, financial technology innovation represents a strategic resource that can enhance efficiency, expand service outreach, and drive business process transformation in the banking sector, including rural banks (Zhao et al., 2022). However, for such innovation to truly generate added value, organizations require adaptive leadership—the ability of leaders to respond to change, manage uncertainty, and guide the organization with flexibility. Thus, integrating technological resources and leadership capabilities is crucial in strengthening overall organizational performance. The RBV approach helps explain the importance of collaboration between organizational and individual dimensions in addressing the ongoing challenges of digital transformation (Assensoh-Kodua, 2019).

Furthermore, rural bank leaders must be able to effectively manage the unique challenges and constraints faced by their institutions, such as limited resources, regulatory hurdles, and the need to cater to the specific needs of underserved rural communities (Harjanti et al., 2021). Understanding how these leadership factors shape the interplay between fintech and rural bank performance can provide valuable insights for policymakers, regulators, and rural bank leaders as they work to harness the potential of financial technology to drive financial inclusion and sustainable development (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018; Gu, 2021).

By addressing this research gap, future studies can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the leadership–fintech–performance nexus in the context of rural banking, ultimately informing the design and implementation of effective strategies for fintech adoption and rural bank transformation. This study makes key contributions in several aspects, including the following:

- Analyzing the impact of fintech innovation on the performance of rural banks, with a focus on reducing operational costs and enhancing financial inclusion;

- Exploring the role of adaptive leadership in the adoption of fintech in rural banks and how this adaptive leadership can improve performance and sustainability;

- Conducting a comparative analysis of fintech adoption in rural banks in Indonesia and other developing countries and providing practical insights for policymakers and bank leaders on optimizing technology for financial inclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Financial Technology and Bank Performance

The association between financial technology innovation and bank performance has been widely studied, yielding mixed findings. Zhao et al. (2022) found that fintech innovation positively influences the performance of Chinese banks, highlighting its role as a key driver of efficiency and growth in the financial industry. Fintech has reshaped traditional banking operations by enhancing digital transactions, optimizing risk management, and expanding financial services. However, other studies suggest that fintech’s disruptive nature can negatively affect banks. Phan et al. (2020) and Thakor (2020) found that fintech innovations, such as loan platforms and online investments, reduce banks’ profitability by increasing competition and altering traditional financial models. These contrasting perspectives indicate that while fintech brings opportunities, it also poses significant challenges for banks.

While these studies primarily focus on large commercial banks, their findings can also be extended to rural banks, which play a crucial role in serving underserved communities. In rural banks, fintech offers significant benefits by helping to optimize lending processes, reduce operational costs through automation, and enhance accuracy in credit risk analysis. For example, Zhu and Guo (2024) discuss how fintech, particularly peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, enables rural banks to serve communities that have traditionally lacked access to financial services more effectively. These technologies allow the provision of loans to underserved populations without requiring substantial investments in physical infrastructure, thereby reducing operational costs while enhancing service delivery.

The implementation of technologies such as P2P lending enables rural banks to serve underserved communities more effectively while expanding their market reach without the need for significant infrastructure investments. Research by Wahyuni et al. (2024) suggests that P2P lending significantly contributes to bank performance, particularly in terms of increased lending and operational efficiency in Islamic banks, as well as in rural banks in Indonesia. The positive outcomes from the integration of P2P lending in rural banks are driven by its ability to lower transaction costs and enhance credit accessibility for rural borrowers, as demonstrated by Najaf et al. (2022), who highlight that during the COVID-19 pandemic, P2P lending became a primary alternative for borrowers unable to access traditional credit services, underlining how fintech acts as a solution for financial inclusion in rural areas.

Beyond fintech, leadership characteristics play a crucial role in shaping organizational and financial performance. Wamburu et al. (2022) demonstrated that adaptive leadership significantly influences the performance of insurance companies, emphasizing the importance of leaders who can navigate dynamic environments. Similarly, Al-Matari (2019) examined the relationship between executive characteristics and corporate performance in the financial sector, revealing that individual director performance positively impacts financial outcomes. However, factors such as executive team size and professional certifications were found to have no significant effect, suggesting that leadership effectiveness is more dependent on decision-making abilities than formal qualifications.

The role of CEOs in banking performance has also been explored. Gupta and Mahakud (2020) analyzed the impact of CEO characteristics on Indian commercial banks, finding that experienced CEOs contribute to superior financial performance. Their study highlighted a nonlinear relationship between CEO tenure and bank performance, suggesting that leadership experience enhances decision-making capabilities and strategic foresight. This reinforces the argument that strong leadership is essential for banks to adapt to technological advancements and competitive pressures.

Overall, existing research underscores the complex interplay between fintech innovation, leadership, and financial performance; while fintech drives innovation, its disruptive effects necessitate strong adaptive leadership to ensure sustainable bank performance. Future research should further explore how financial institutions can integrate fintech advancements while leveraging effective leadership strategies to maintain long-term stability and competitiveness.

Given these challenges and opportunities, the resource-based view (RBV) theory offers a valuable framework for understanding how financial institutions can leverage fintech innovations as strategic resources. According to RBV, competitive advantage arises from an organization’s ability to manage resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (Wernerfelt, 1984). In the context of fintech, these resources include technological infrastructure, digital capabilities, and leadership competencies. For fintech to drive sustainable performance, it must be supported by adaptive leadership that can align technological innovations with the organization’s strategic objectives. Adaptive leaders can harness these resources effectively, enabling banks to navigate digital disruption while maintaining competitive advantage (Cortellazzo et al., 2019). Thus, integrating fintech innovation and leadership capabilities becomes a key factor in achieving long-term success and resilience in the banking sector, highlighting the importance of both technological and managerial resources in overcoming the challenges posed by digital transformation.

2.2. Development of Financial Technology Regulations in Indonesia

The rapid advancement of technological innovation and digitalization has significantly impacted the global financial sector, including Indonesia (Kharisma, 2021). Financial technology (fintech) refers to the application of new technologies in financial services, enhancing accessibility, efficiency, and security (Hapsari et al., 2019). Fintech development focuses on multichannel assistance, cloud-based financial services, global transactions with minimal intermediaries, and mobile payments that offer security and speed (Abad-Segura et al., 2020). The use of fintech in banking is not a new phenomenon, dating back to the 1980s, and has continuously evolved to streamline financial operations, optimize data collection, and reduce non-performing loans (Broby, 2021; Lagna & Ravishankar, 2022).

In Indonesia, fintech is categorized as part of digital financial services and is regulated by various legal frameworks to ensure consumer protection and financial stability (Rahayu & Rahadi, 2023). Key regulations include Financial Services Authority Regulation No. 77/POJK.01/2016, which governs peer-to-peer lending services; Law No. 11/2008, which regulates electronic transactions; and Financial Services Authority Regulation No. 1/POJK.07/2013, which emphasizes consumer protection in financial services. Additionally, Law No. 8/1999 and Government Regulation No. 82/2012 ensure legal certainty for electronic transactions, while Bank Indonesia Regulation No. 19/12/PBI/2017 mandates fintech providers to register with the central bank (Widarwati et al., 2022; Wirani et al., 2021).

The emergence of fintech in Indonesia has addressed various societal needs by providing alternative financial solutions that are practical, efficient, and inclusive (Kurniasari, 2021). Key fintech applications include crowdfunding, which facilitates fundraising for social initiatives; microfinancing, which provides financial access to underserved communities; peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, which simplifies borrowing processes; market comparison platforms, which aid financial planning; and digital payment systems, which streamline bill payments and transactions (Prasastisiwi et al., 2021; Putra et al., 2023). With continuous regulatory support and technological advancements, fintech in Indonesia is poised to further enhance financial inclusion and economic growth.

2.3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

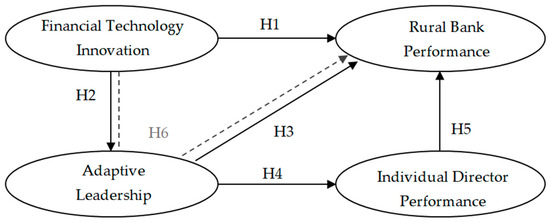

Theoretical framework and hypotheses development provide a structured basis to explain the relationship between research variables. Hypotheses are formulated as predictions about how one variable may influence another. The following are the hypotheses proposed in this study as follows:

2.3.1. Financial Technology Innovation and Rural Bank Performance

A term used to refer to the application of new technology in financial services (Abad-Segura et al., 2020), financial technology in banking is not a new phenomenon. It combines financial services with technology, transforming the business model from conventional to modern and making transaction processes faster and more efficient. From a theoretical perspective, financial technology innovation aligns with the resource-based view (RBV), which posits that banks achieve superior performance by developing and leveraging unique, valuable, and inimitable capabilities (Indriyani et al., 2025).

Research by Zhao et al. (2022) indicates that financial technology innovation is a significant manifestation of innovation in the financial industry and has a profound impact on the banking, helping reduce information asymmetry issues arising from distance constraints and able to lower transaction costs. Banking is an information-intensive and technology-based business, so the development of financial technology can help banks expand their business, thereby enhancing bank performance (Tcvetova, 2020). Therefore, the proposed hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a relationship between financial technology innovation and the performance of rural banks.

2.3.2. Financial Technology Innovation and Adaptive Leadership

The rapid advancement of financial technology (fintech) has not only transformed the operational landscape of financial institutions but also introduced complex challenges that demand adaptive and responsive leadership. Financial technology innovation compels organizational leaders to shift away from traditional decision-making models toward leadership approaches that are more agile, flexible, and learning-oriented (Faiz et al., 2024). Leaders are required to navigate uncertainty, drive organizational transformation, and mobilize teams toward innovation adoption (Schiuma et al., 2024). As fintech reshapes workflows, customer engagement, and organizational culture, leaders must develop new competencies to adapt to ongoing technological changes, manage resistance, and align innovation with strategic objectives (Singh & Jha, 2024).

Existing literature suggests that technological innovation drives the evolution of leadership styles (Hoffman & Vorhies, 2017). Organizations undergoing digital transformation tend to foster adaptive leadership behaviors to sustain performance and remain competitive in dynamic environments and adaptive leadership ensures organizational continuity and success in the digital era (Candrasa et al., 2024). Leaders who possess the ability to guide and leverage technology are referred to as digital leaders. Digital leadership goes beyond merely understanding technology; it involves formulating a vision that integrates technology into business strategy, fostering a culture of innovation, enhancing employees’ digital skills, focusing on customer needs, and creating organizational flexibility (Wang et al., 2022). Developing a positive public image is vital for banks to minimize the adverse effects of swayer factors and ensure continued customer retention (Akbar et al., 2024). Therefore, the proposed hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There is a relationship between financial technology innovation and adaptive leadership.

2.3.3. Adaptive Leadership and Rural Bank Performance

Adaptive leadership demonstrates that a leader has the ability and intelligence to face various situations in different events (Mweu & Mung’ara, 2021). This means that adaptive leadership is not about overthinking but rather about quickly taking action, seeking solutions to solve problems according to the needs (Briscoe & Nyereyemhuka, 2022). An adaptive leader is someone who can maintain a proactive mindset to engage in every change that occurs (Wong & Chan, 2018).

Research by Wamburu et al. (2022) shows that adaptive leadership has a significant influence on organizational performance. It is important for leaders to consider the dimensions of adaptive leadership to gain perspective through reflection, identify challenges, and solve problems effectively, thus impacting organizational or company performance (Mahfouz et al., 2022). The actions of leaders affect the business areas they lead and can create important relationships between employee performance and the organization (Horan, 2020; Madyan et al., 2023). Therefore, the proposed hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

There is a relationship between adaptive leadership and the performance of rural banks.

2.3.4. Adaptive Leadership and Director’s Individual Performance

Adaptive leadership focuses on a leader’s ability to inspire organizational members to adapt to environmental changes (Monyei et al., 2023). An adaptive leader is seen as someone who easily adjusts to new changes and circumstances. Adaptive leadership is a practical leadership framework that helps individuals and organizations adapt and thrive in challenging environments.

Directors who implement adaptive leadership will be able to adjust strategies and actions according to evolving conditions, thus enhancing effectiveness and efficiency (Schulze & Pinkow, 2020). This flexibility allows directors to address challenges creatively and innovatively and make informed decisions. Applied adaptive leadership also promotes the development of a strong team and empowers individuals within the organization, ultimately supporting director individual performance (Zhao et al., 2022). Therefore, the proposed hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

There is a relationship between adaptive leadership and the director’s individual performance.

2.3.5. Director’s Individual Performance and Rural Bank Performance

As top leaders, directors play a key role in formulating strategies and managing banking resources (Vo et al., 2021). Effective director performance includes the ability to make appropriate strategic decisions, manage risks, and ensure compliance with all existing regulations (Naim & Rahman, 2022). These aspects are considered to help rural banks achieve financial and operational goals, enhancing profitability and competitiveness (Kathawala & Sharma, 2021).

Research by Al-Matari (2019) demonstrates a positive and significant influence of several executive management characteristics, including director individual performance, on company performance. Executive management plays a role in assisting in the achievement of company goals (Li & Wu, 2022; Madyan et al., 2023). Additionally, a study by Gupta and Mahakud (2020) indicates that professional superiors can enhance performance. Experienced superiors contribute to maximum performance, thus influencing banking performance. Therefore, the proposed hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

There is a relationship between the performance of individual directors and the performance of rural banks.

2.3.6. Mediator Role of Adaptive Leadership

Innovation in financial technology has become a key strategic factor in transforming the banking industry, including in the rural banking sector. This innovation includes digitalizing service processes, automating risk management, using big data for credit analysis, and integrating mobile and internet-based financial services (Chakraborty, 2020). Previous studies have shown that fintech adoption can enhance operational efficiency, expand service accessibility, and strengthen the competitiveness of financial institutions, ultimately leading to improved organizational performance (Tcvetova, 2020; Zhao et al., 2022).

The availability of technology does not solely determine the success of financial technology innovation implementation but also depends on the organization’s readiness to manage the changes it brings—one of which is adaptive leadership. Leadership identity strongly resonates with individuals, reinforcing the legitimacy and essential role of leadership in guiding and influencing others (Abbas et al., 2023). Adaptive leadership refers to a leader’s ability to respond to complex external dynamics, guide organizational cultural change, and empower employees to face new challenges flexibly and proactively (Wong & Chan, 2018). Adaptive leadership can bridge the gap between technological innovation and performance outcomes in financial institutions such as rural banks, which often face resource limitations, and conventional organizational structures. Adaptive leaders are capable of translating technological potential into operational strategies that are relevant to the local context (Ramesh et al., 2023). They also play a crucial role in fostering an innovative culture, mitigating resistance to change, and enhancing the organization’s capacity to adopt technology effectively (Lei et al., 2019; Srimulyani et al., 2025).

Previous research has shown that leadership style mediates the relationship between exploitative and explorative innovation and firm performance (Berraies & Bchini, 2019). Therefore, it can be assumed that adaptive leadership is a mediating variable linking financial technology innovation to rural bank performance. Therefore, the proposed hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Adaptive leadership mediates the relationship between financial technology innovation and rural bank performance.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

The study focused on rural banks operating in the Indonesian banking industry, aiming to explore the mechanisms of financial practices. A total of 305 survey questionnaires were distributed to executives, including C-level executives and mid-level managers directly involved in the banks’ operations and performance. The sampling process was conducted extensively, without geographic limitations, covering both central and branch offices across various regions in Indonesia.

3.2. Measurement of Variables

This study employed a structured questionnaire to collect data, ensuring the reliability and validity of the measurements through the careful selection of items from established research instruments. The study consisted of four variables: financial technology innovation, adaptive leadership, director individual performance, and rural bank performance. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), facilitating a nuanced capturing of participant attitudes and perceptions. The questionnaire items distributed to the study sample are shown in Appendix A, Table A1 and Table A2.

3.3. Analytical Approach

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) has gained widespread recognition as a powerful statistical tool across diverse disciplines, including human resource management, strategic management, accounting, operations management, marketing, and information systems. Its increasing adoption stems from its flexibility and robustness in handling complex latent variable models, which are commonly found in advanced research settings (Cheah et al., 2019; Hair et al., 2011), as illustrated by the conceptual structure presented in Figure 1. PLS-SEM is a variance-based structural equation modeling technique that consists of two main components: the measurement model and the structural model (Hair et al., 2019). The measurement model defines how latent constructs are represented by their observed indicators, focusing on the reliability and validity of these relationships. Meanwhile, the structural model examines the hypothesized causal relationships among latent constructs, assessing the strength and significance of path coefficients and the model’s explanatory power. In this study, PLS-SEM analysis was conducted using SmartPLS software version 3.2.9, which provides comprehensive features for evaluating high-order models and improving predictive accuracy, as suggested by Hair et al. (2017).

Figure 1.

Research model. Source(s): Authors’ own creation.

3.4. The Common Method Bias Assessment

We first engaged in the common method bias assessment. As a procedural step, we reassured participants that their responses would remain confidential and anonymous (MacKenzie & Podsakoff, 2012). After data collection, we conducted a full collinearity test based on Kock and Lynn (2012) to detect both multicollinearity and common method bias (CMB). The results suggest that the variance inflation factor values are between 1.000 and 1.148, which is lower than 3.3, indicating no serious multicollinearity or CMB issues. To further minimize bias, we applied several procedural remedies, including ensuring respondent anonymity, utilizing validated measurement instruments, and employing bootstrapping techniques. Hence, common method bias is unlikely to be a threat.

3.5. Sampling Design

In social science research, both probability and non-probability sampling techniques are widely used (Ali et al., 2022). While probability sampling ensures broader generalizability, non-probability methods are often applied when a sampling frame is not available. This study adopted purposive sampling, a non-probability technique suitable for selecting participants with specific expertise relevant to the research objectives (Ali et al., 2022). Bank executives were targeted due to their direct involvement in adaptive leadership and rural bank performance, ensuring the reliability of the data collected.

Given the use of structural equation modeling (SEM), an adequate sample size is crucial. Based on the rule of thumb, five times the number of indicators, the minimum sample size required for 38 indicators is 190 participants. However, this study collected 305 responses to enhance data accuracy and measurement validity (Hair et al., 2017).

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Demographic

The study sample consisted of 305 participants distributed across two levels of management (Table 1): 165 from the top-level manager and 140 from the middle-level manager. The number of male respondents was 170 (56%), and the number of female respondents was 135 (44%). Of the final usable sample, 34% had an office located in West Java and 73% had work experience of more than seven years. The respondents’ detailed descriptions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of respondents (n = 305).

4.2. Measurement Model

The evaluation of the reflective measurement model began with analyzing indicator loadings, where values above 0.6, as presented in Table 2, indicate satisfactory validity (Hair et al., 2014). Several indicators were dropped due to factor loadings below the 0.6 threshold, leaving only the indicators presented in Table 2. Following this, internal consistency was assessed using composite reliability (CR), with values between 0.70 and 0.90 deemed satisfactory; the CR values in this study all exceed 0.8, confirming strong inter-item correlations (Gefen et al., 2000). Additionally, convergent validity was established by ensuring that the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct was above 0.50, as shown in Table 2, thereby confirming that each construct accounts for sufficient variance and validating the overall reliability and validity of the measurement model (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 2.

Results of reliability and validity.

The criterion developed by Fornell and Larcker (1981) is employed to assess the discriminant validity. According to Table 3, the values along the main diagonal are greater than the values outside the diagonal. Thus, this study has successfully demonstrated discriminant validity. Additionally, we found that 19% of the variance could be explained by the current model and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value is 0.073. According to Hair et al. (2017), the model is considered to have a good level of fit if the SRMR value is less than 0.10 or 0.08. The results of this evaluation indicate that the model has adequate goodness of fit.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity using Fornell and Larker criterion.

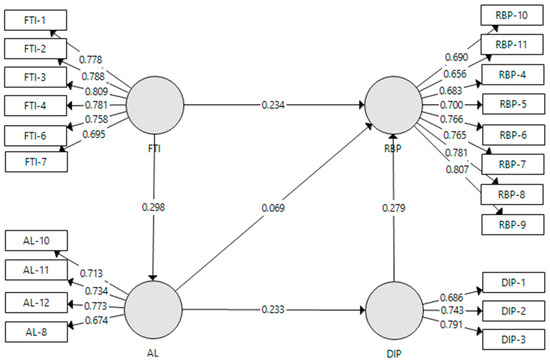

4.3. Structural Model

After validating the measurement model, the structural model was examined, focusing on path coefficients and significance, using t-values from bootstrapping with 5000 samples (Hair et al. 2017). The structural equation model (SEM) depicted in Figure 2 presents a comprehensive view of the relationships between financial technology innovation (FTI), adaptive leadership (AL), director individual performance (DIP), and rural bank performance (RBP). The model offers significant insights into how these variables interact to influence rural bank performance, with clear path coefficients that elucidate the strength and direction of these relationships.

Figure 2.

The structural model and path coefficients values for the total sample.

Table 4 presents the findings of this study. According to the results, financial technology innovation was found to be positively related to rural bank performance (H1). Thus, the results of H1 (β = 0.234, t = 4.237, and p < 0.01) were found to be statistically significant; therefore, we concluded that H1 was supported. The results of the present study also supported H2, which stated that financial technology innovation is positively related to rural bank performance (β = 0.298, t = 4.498, and p < 0.01). However, there is no significant association between adaptive leadership and rural bank performance (β = 0.069, t = 1.098, and p > 0.1), indicating that H3 is not supported. On the other hand, the result of the direct path analysis for H4 (β = 0.233, t = 3.123, and p < 0.01), which stated that adaptive leadership significantly positively influences director individual performance, also supported H4. Lastly, the study finds a statistically significant association between director individual performance and rural bank performance (β = 0.279, t = 4.450, and p < 0.01), thus supporting H5.

Table 4.

Structural model assessment (n = 305).

4.4. Mediation Analysis

Our analysis showed that adaptive leadership is an insignificant mediator between financial technology innovation and rural bank performance (β = 0.021; p > 0.1) (see Table 5). Hypothesis H6, “Adaptive leadership mediates the relationship between financial technology innovation and rural bank performance”, was not supported by this study.

Table 5.

Mediation assessment (n = 305).

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical/Research Implications

Our first hypothesis tests the relationship between financial technology (fintech) innovation and rural bank performance. Based on the analysis results presented in Table 5, financial technology innovation significantly positively affects rural bank performance. This positive relationship indicates that rural banks capable of integrating digital innovation tend to perform better than those without optimally adopting technology. This result is consistent with previous studies by Tcvetova (2020) and Zhao et al. (2022) which show that financial technology innovation substantially impacts banking performance. Financial technology innovation enables rural banks to reach previously underserved segments of the population.

Meanwhile, our second hypothesis examines the relationship between financial technology innovation and adaptive leadership. We found a significant positive relationship between financial technology innovation and adaptive leadership. This finding suggests that the advancement and implementation of financial technology within financial organizations drive the need for a more adaptive leadership style. Leaders are increasingly required to be responsive to external dynamics, capable of flexibly mobilizing resources and empowering their teams to adapt to change (Schiuma et al., 2024). This relationship is supported by the study conducted by Hoffman and Vorhies (2017).

However, testing our third hypothesis shows that adaptive leadership has a positive but insignificant effect on rural bank performance in Indonesia. This result is inconsistent with the hypothesis developed based on previous studies indicating a significant positive relationship between adaptive leadership and rural bank (BPR) performance (Horan, 2020; Mahfouz et al., 2022; Wamburu et al., 2022). The lack of significance may be due to the complex relationship between the two variables. The relationship between adaptive leadership and BPR performance is not always direct and may be influenced by other factors, such as organizational innovation and market orientation (Djalil et al., 2023).

The testing of our fourth hypothesis shows a significant positive relationship between adaptive leadership and director individual performance. This finding indicates that directors who exhibit an adaptive leadership style tend to demonstrate better individual performance. This aligns with previous literature, which suggests that adaptive leadership enhances executive performance through empowerment, the formation of responsive teams, and developing context-based strategies (Schulze & Pinkow, 2020; Zhao et al., 2022). In the long term, directors with adaptive leadership are capable of creating an innovative and resilient work environment, which contributes not only to individual performance but also to the organization’s overall performance.

Furthermore, our fifth hypothesis tests the effect of a director individual performance on rural bank performance, revealing a significant positive relationship between the two. This finding reinforces the view that the performance of top leaders, particularly directors, plays a strategic role in determining the direction and success of an organization. Directors who can effectively carry out their managerial roles can establish operational stability and drive the achievement of both financial and non-financial organizational goals. High-performing leaders typically possess a strong vision, the ability to respond quickly to market changes, and the drive to foster innovation within the organization. This result is consistent with previous research demonstrating that the characteristics and performance of executive management, including directors, significantly impact company performance (Al-Matari, 2019; Gupta & Mahakud, 2020; Li & Wu, 2022). Directors with experience, knowledge, and strong leadership capabilities are better equipped to guide their organizations toward sustainable growth and profitability.

Our sixth hypothesis examines the mediating mechanism of adaptive leadership in the relationship between financial technology innovation and rural bank performance. The analysis rejects the hypothesized relationship. Adaptive leadership does not mediate the relationship between financial technology innovation and rural bank performance. This finding contradicts previous studies, such as Berraies and Bchini (2019) and Ma et al. (2024), which suggested that adaptive leadership is vital in linking financial technology innovation to improved organizational performance. The inconsistency between this result and earlier literature can be interpreted through several possibilities—for instance, the role of adaptive leadership within the context of rural banks in Indonesia appears to be not yet fully optimized (Wasiaturrahma et al., 2020). This reflects a gap between leadership capabilities in responding to technological changes and the organizational need to integrate financial innovation into business strategy comprehensively. Resource limitations, both in terms of technological infrastructure and managerial digital competence, may act as constraining factors that hinder the effectiveness of adaptive leadership in mediating the impact of fintech innovation on bank performance (Bhutto et al., 2023). Many rural banks still face challenges in strategically adopting technology, where digitization efforts tend to remain operational rather than transformational (Samsudin et al., 2024).

These results suggest that while adaptive leadership is essential, it may not be sufficient as a catalyst for translating technological innovation into superior organizational performance. Other variables, more relevant and contextual, are likely better suited to explain this relationship. Factors such as digital capability, organizational agility, or technology readiness need to be explored further as alternative mediators that could more accurately capture how fintech innovation influences rural bank performance (Jun et al., 2022). This study may enrich the academic discourse on leadership effectiveness in the digital era. Furthermore, these findings underscore the importance of building a technologically prepared and strategically adaptive organizational foundation so that digital innovation can generate real added value for the performance of financial institutions, particularly rural banks.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Findings from the study offer a number of implications for managers and other stakeholders in the rural banking ecosystem. There is the need for rural bank managers to proactively adopt and support digital transformation initiatives. These innovations not only streamline operations but also foster the development of adaptive leadership within the organization (Hoffman & Vorhies, 2017). Management must ensure that fintech adoption is not merely symbolic but fully integrated into service systems, credit processes, risk management, and financial reporting. Investments in digital payment systems, big data-based credit scoring, and mobile banking platforms can enhance operational efficiency and expand service outreach to unbanked populations in rural areas (Setiawan et al., 2021).

Rural banks must emphasize leadership capacity development through training programs, coaching, and benchmarking with financial institutions that have successfully undergone digital transformation (Winasis et al., 2021). Adaptive leaders can steer organizations flexibly, manage resistance to change, and initiate innovations that align with local market needs (Schulze & Pinkow, 2020). In addition, management should develop recruitment and evaluation systems that prioritize strategic competencies rather than focus solely on administrative aspects or previous experience. Directors with a strong vision, technological expertise, and practical communication skills are better equipped to lead teams, make strategic decisions, and foster an innovative and collaborative organizational culture (Kurzhals et al., 2020).

Close collaboration between technological development and managerial structure reinforcement is essential to optimize the synergy between innovation and leadership. Decisions regarding technology implementation must involve top-level executives directly to ensure that digital strategies align with organizational goals (Gilli et al., 2024) Adaptive leaders serve as catalysts in ensuring that every adopted innovation is internalized and internalized across the organization (Susanty et al., 2024). Rural banks must build a digital ecosystem that supports technological advancement and organizational adaptability. This includes strengthening IT infrastructure, formulating internal policies that are flexible toward change, and establishing strategic partnerships with fintech service providers and other technology platforms. By creating a collaborative, data-driven ecosystem, rural banks will be better positioned to compete and grow amidst the increasingly intense digital disruption.

5.3. Recommended Strategies

Based on the study’s findings, although financial technology innovation significantly improves rural bank performance, the expected mediating role of adaptive leadership was not supported, indicating a gap between leadership responsiveness and technological advancement. To address this, rural banks must implement integrated strategies that strengthen the alignment between digital transformation initiatives and leadership effectiveness. First, leadership development programs should focus on enhancing digital literacy, agility, and strategic foresight among directors and managers, enabling them to lead innovation with clarity and confidence. Second, banks need to establish internal structures that foster cross-functional collaboration between technology units and executive leadership, ensuring that digital initiatives are embedded across operational and strategic levels. Third, adaptive leadership should be reinforced not as a standalone driver but as part of a broader ecosystem that includes digital capability building, agile organizational processes, and performance-based leadership evaluation systems. Lastly, to fully leverage the potential of fintech innovation, rural banks should consider complementary factors such as organizational culture, digital readiness, and innovation-oriented governance as alternative or supporting mechanisms in achieving sustainable performance improvement. These strategies are essential for transforming fintech adoption from operational upgrades into long-term value creation, driven by effective and forward-thinking leadership.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

As with many other studies, this study has some limitations worthy of mention. These limitations, however, did not affect the conclusions drawn but are necessary to guide future studies. First, the findings of this study are derived from cross-sectional data collected at a specific point in time, consistent with methodological practices in organizational research. Consequently, the study does not assert causal inferences, which would be more appropriately addressed through longitudinal or experimental research designs. However, the proposed associations among key constructs are grounded in established theoretical frameworks and supported by prior empirical evidence.

Second, the present study has examined financial technology innovation as the sole antecedent to adaptive leadership. The conceptual model may have overlooked other relevant antecedents to adaptive leadership. While the results show that adaptive leadership is significantly influenced by financial technology innovation, adaptive leadership could be affected by other factors, such as training and development programs that cultivate essential skills—such as emotional intelligence, decision-making under uncertainty, and collaboration—are pivotal in preparing leaders to navigate complex challenges (Sott & Bender, 2025). Future studies may examine other antecedents and outcomes of adaptive leadership to form a more comprehensive framework.

Third, we use leadership style (adaptive leadership) to improve rural bank performance; it would be reasonable for future researchers to test a moderator, or other leadership styles (i.e., agile leadership, responsible leadership, and change-oriented leadership) with different outcomes. By addressing these limitations and expanding the scope of future research, scholars can contribute to a more robust and globally relevant body of knowledge on rural banks’ performance.

Additionally, while this study focuses specifically on Indonesian firms, the proposed model has broader applicability and can be extended to other real-world contexts, particularly in developing countries with similar economic structures and regulatory pressures. Future research is encouraged to test this model in diverse geographical settings or industries, to validate its robustness and enhance generalizability across contexts.

6. Conclusions

This study offers valuable insights into the factors influencing rural bank performance among rural banking users in Indonesia, with a focus on financial technology innovation, adaptive leadership, and individual director performance. By applying the resource-based view (RBV) theory, this research explored how these factors shape rural bank performance. Our findings indicate that financial technology innovation and director individual performance are significantly linked to rural bank performance, highlighting the importance of these factors in enhancing operational efficiency and ensuring institutional sustainability. In contrast, adaptive leadership did not show a significant direct impact on rural bank performance. This suggests that while adaptive leadership is essential, it is not sufficient on its own to drive performance improvements. This finding indicates the need for more integrative leadership approaches that combine adaptive leadership with institutional readiness, employee alignment, and strategic clarity to enhance performance effectively.

These findings contrast with previous research that highlights adaptive leadership as crucial for organizational success. For example, studies such as those by Wamburu et al. (2022) and Maulana et al. (2022) emphasize the importance of adaptive leadership in driving performance. In contrast, our research suggests that fintech innovation may have a more immediate impact on rural bank performance. Moreover, the lack of a significant effect of adaptive leadership in this study adds a novel contribution to the literature, suggesting that other factors, such as organizational readiness or digital transformation, might be more prominent in improving performance in rural banking sectors.

In conclusion, this study enhances our understanding of how rural banks can leverage financial technology innovations and effective executive leadership to improve their performance. It emphasizes the need for a holistic leadership model that integrates adaptive leadership with broader organizational capabilities. Future research could explore alternative leadership styles and digital transformation strategies to better understand how rural banks can thrive in the rapidly evolving fintech landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T. and M.M.; methodology, R.T. and I.H.; software, I.H.; validation, M.M., I.H. and H.M.; formal analysis, R.T.; investigation, R.T.; resources, R.T.; data curation, M.M. and H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T.; writing—review and editing, I.H.; visualization, H.M.; supervision, M.M. and I.H.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in compliance with ethical research standards and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Universitas Airlangga on 23 May 2025. Additionally, the research involved no sensitive or high-risk inquiries, and all participant responses were collected anonymously to ensure confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author would also like to sincerely thank Hamidah Dwi Nita and Fritzy Vasya Anandiva for their support throughout the research process. Their assistance played an important role in the successful completion of this study. The researcher also appreciates the considerable time and work of the reviewers and the editor to expedite the process. Their commitment and expertise were crucial in making this work a success. I appreciate your unwavering help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FTI | financial technology innovation |

| AL | adaptive leadership |

| DIP | director individual performance |

| RBP | rural bank performance |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire items for C-level executives.

Table A1.

Questionnaire items for C-level executives.

| C-Level Executives | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Codes | Item Description | Reference |

| Financial Technology Innovation | FTI-1 | The quality of our digital financial solutions is superior compared to our competitors. | (Khin & Ho, 2019; Paladino, 2007) |

| FTI-2 | The features of our digital financial solutions are superior compared to our competitors. | ||

| FTI-3 | The applications of our digital financial solutions are totally different from our competitors. | ||

| FTI-4 | Our digital financial solutions are different from our competitors’ in terms of product platform. | ||

| FTI-5 | Our new digital financial solutions are minor improvements of existing products. | ||

| FTI-6 | Some of our digital financial solutions are new to the market at the time of launching. | ||

| FTI-7 | The applications of our digital solutions are totally different from the applications of our main competitors’ solutions. | ||

| Adaptive Leadership | AL-1 | My partner quickly grasps what kind of leadership behavior is optimal for a specific situation. | (Nöthel et al., 2023) |

| AL-2 | My partner realizes when his/her leadership style should change due to changes in the situation. | ||

| AL-3 | My partner tries to understand the needs of his/her subordinates and adjusts his/her responses in a fitting way. | ||

| AL-4 | My partner recognizes changes in task priorities and the need to modify his or her leadership behavior. | ||

| AL-5 | My partner is able to focus on and manage the task at hand while keeping an eye on employee’s needs. | ||

| AL-6 | My partner is able to continuously adjust his/her behavior to the right degree to the circumstances at hand. | ||

| AL-7 | My partner is capable of adjusting his/her leadership style based on the needs of his/her subordinates. | ||

| AL-8 | My partner is able to balance opposite types of behavior (e.g., controlling vs. empowering) in a way that is appropriate for the situation. | ||

| AL-9 | My partner is able to lead through difficulties, ambiguity and complexity. | ||

| AL-10 | My partner is able to balance various conflicting needs of different stakeholders. | ||

| AL-11 | My partner reacts to unforeseen circumstances or problems with an appropriate response. | ||

| AL-12 | My partner adjusts his or her leadership behaviors to the demands of the specific situation. | ||

| AL-13 | My partner adapts his or her leadership behavior when unexpected events occur. | ||

| AL-14 | My partner stays focused on the goal while remaining flexible in what leadership approaches he/she uses to achieve the goal. | ||

| AL-15 | My partner easily switches between directive and shared leadership according to the actual situation. | ||

| Rural Bank Performance | RBP-1 | The company has up-to-date equipment. | (Adil, 2013) |

| RBP-2 | The company has physical facilities. | ||

| RBP-3 | The company has visual service material. | ||

| RBP-4 | The company has services delivered at promised time. | ||

| RBP-5 | The company has service right the first time. | ||

| RBP-6 | The company is trustworthy. | ||

| RBP-7 | The company has safe transactions. | ||

| RBP-8 | The company has prompt service. | ||

| RBP-9 | The company has customer requests. | ||

| RBP-10 | The company has informed you in advance. | ||

| RBP-11 | The company has specific needs. | ||

| RBP-12 | The company has personal assistance. | ||

| RBP-13 | The company has the best interest. | ||

| Director Individual Performance | DIP-1 | Inadequate performance (including inadequate commitment) by Directors is addressed promptly through peer-remediation or by our Chair taking appropriate action. | (Asahak et al., 2018) |

| DIP-2 | Directors act independently of management. | ||

| DIP-3 | Appropriate action would be taken if we had undesirable behavior. | ||

Source(s): Authors’ own creation.

Table A2.

Questionnaire items for mid-level managers.

Table A2.

Questionnaire items for mid-level managers.

| Mid-Level Managers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Codes | Item Description | Reference |

| Financial Technology Innovation | FTI-1 | The quality of our digital financial solutions is superior compared to our competitors. | (Khin & Ho, 2019; Paladino, 2007) |

| FTI-2 | The features of our digital financial solutions are superior compared to our competitors. | ||

| FTI-3 | The applications of our digital financial solutions are totally different from our competitors. | ||

| FTI-4 | Our digital financial solutions are different from our competitors’ in terms of product platform. | ||

| FTI-5 | Our new digital financial solutions are minor improvements of existing products. | ||

| FTI-6 | Some of our digital financial solutions are new to the market at the time of launching. | ||

| FTI-7 | The applications of our digital solutions are totally different from the applications of our main competitors’ solutions. | ||

| Adaptive Leadership | AL-1 | My supervisor quickly grasps what kind of leadership behavior is optimal for a specific situation. | (Nöthel et al., 2023) |

| AL-2 | My supervisor realizes when his/her leadership style should change due to changes in the situation. | ||

| AL-3 | My supervisor tries to understand the needs of his/her subordinates and adjusts his/her responses in a fitting way. | ||

| AL-4 | My supervisor recognizes changes in task priorities and the need to modify his or her leadership behavior. | ||

| AL-5 | My supervisor is able to focus on and manage the task at hand while keeping an eye on employee’s needs. | ||

| AL-6 | My supervisor is able to continuously adjust his/her behavior to the right degree to the circumstances at hand. | ||

| AL-7 | My supervisor is capable of adjusting his/her leadership style based on the needs of his/her subordinates. | ||

| AL-8 | My supervisor is able to balance opposite types of behavior (e.g., controlling vs. empowering) in a way that is appropriate for the situation. | ||

| AL-9 | My supervisor is able to lead through difficulties, ambiguity and complexity. | ||

| AL-10 | My supervisor is able to balance various conflicting needs of different stakeholders. | ||

| AL-11 | My supervisor reacts to unforeseen circumstances or problems with an appropriate response. | ||

| AL-12 | My supervisor adjusts his or her leadership behaviors to the demands of the specific situation. | ||

| AL-13 | My supervisor adapts his or her leadership behavior when unexpected events occur. | ||

| AL-14 | My supervisor stays focused on the goal while remaining flexible in what leadership approaches he/she uses to achieve the goal. | ||

| AL-15 | My supervisor easily switches between directive and shared leadership according to the actual situation. | ||

| Rural Bank Performance | RBP-1 | The company has up-to-date equipment. | (Adil, 2013) |

| RBP-2 | The company has physical facilities. | ||

| RBP-3 | The company has visual service material. | ||

| RBP-4 | The company has services delivered at promised time. | ||

| RBP-5 | The company has service right the first time. | ||

| RBP-6 | The company is trustworthy. | ||

| RBP-7 | The company has safe transactions. | ||

| RBP-8 | The company has prompt service. | ||

| RBP-9 | The company has customer requests. | ||

| RBP-10 | The company has informed you in advance. | ||

| RBP-11 | The company has specific needs. | ||

| RBP-12 | The company has personal assistance. | ||

| RBP-13 | The company has the best interest. | ||

| Director Individual Performance | DIP-1 | Inadequate performance (including inadequate commitment) by Directors is addressed promptly through peer-remediation or by our Chair taking appropriate action. | (Asahak et al., 2018) |

| DIP-2 | Directors act independently of management. | ||

| DIP-3 | Appropriate action would be taken if we had undesirable behavior. | ||

Source(s): Authors’ own creation.

References

- Abad-Segura, E., González-Zamar, M.-D., López-Meneses, E., & Vázquez-Cano, E. (2020). Financial technology: Review of trends, approaches and management. Mathematics, 8(6), 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A., Ekowati, D., Suhariadi, F., Anwar, A., & Fenitra, R. M. (2023). Technology acceptance and COVID-19: A perspective for emerging opportunities from crisis. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 36(11), 3551–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M. (2013). The relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in India’s rural banking sector: An item analysis and factor-specific approach. The Lahore Journal of Business, 1(2), 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afif, M., & Samsuri, A. (2022). Integration of fintech and Islamic banking in Indonesia: Opportunities and challenges. Cakrawala: Jurnal Studi Islam, 17(1), 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwu, M. E. (2021). Can technology bridge the gap between rural development and financial inclusions? Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 33(2), 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, R. F., Sukoco, B. M., & Nadia, F. N. D. (2024). Borrower switching behaviour on a P2P lending platform: A study of switching path analysis technique. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2422562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaassar, A., Mention, A.-L., & Aas, T. H. (2023). Facilitating innovation in FinTech: A review and research agenda. Review of Managerial Science, 17(1), 33–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhi, I. F., Suhariadi, F., Supriharyanti, E., Rahmawati, E., & Hardaningtyas, D. (2024). Financial technology in recovery: Behavioral usage of payment systems by Indonesian MSMEs in the post-pandemic era. International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems, 15(1), 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. A., Hussin, N., Haddad, H., Al-Ramahi, N. M., Almubaydeen, T. H., & Abed, I. A. (2022). The impact of intellectual capital on dynamic innovation performance: An overview of research methodology. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(10), 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matari, E. M. (2019). Do characteristics of the board of directors and top executives have an effect on corporate performance among the financial sector? Evidence using stock. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20(1), 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanda, C. (2023). Rural banking spatial competition and stability. Economic Analysis and Policy, 78, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M., Nidar, S. R., Komara, R., & Layyinaturrobaniyah, L. (2019). Rural bank efficiency and loans for micro and small businesses: Evidence from West Java Indonesia. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 15(3), 587–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahak, S., Albrecht, S. L., De Sanctis, M., & Barnett, N. S. (2018). Boards of directors: Assessing their functioning and validation of a multi-dimensional measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assensoh-Kodua, A. (2019). The resource-based view: A tool of key competency for competitive advantage. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 17(3), 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulia, M., Yustiardhi, A. F., & Permatasari, R. O. (2020). An overview of Indonesian regulatory framework on Islamic financial technology (fintech). Jurnal Ekonomi & Keuangan Islam, 6(1), 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraies, S., & Bchini, B. (2019). Effect of leadership styles on financial performance: Mediating roles of exploitative and exploratory innovations case of knowledge-intensive firms. International Journal of Innovation Management, 23(3), 1950020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, S. A., Jamal, Y., & Ullah, S. (2023). FinTech adoption, HR competency potential, service innovation and firm growth in banking sector. Heliyon, 9(3), e13967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, P., & Nyereyemhuka, N. (2022). Turning leadership upside-down and outside-in during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 200, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broby, D. (2021). Financial technology and the future of banking. Financial Innovation, 7(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candrasa, L., Cahyadi, L., Cahyadi, W., & Cen, C. C. (2024). Change management strategies: Building organizational resilience in the digital era. Journal of Ecohumanism, 3(7), 4125–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, G. (2020). Evolving profiles of financial risk management in the era of digitization: The tomorrow that began in the past. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(2), e2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Ramayah, T., Memon, M. A., Cham, T.-H., & Ciavolino, E. (2019). A comparison of five reflective–formative estimation approaches: Reconsideration and recommendations for tourism research. Quality & Quantity, 53(3), 1421–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiyanto, W. W., Solikin, I., Purnomo, B. S., & Andriana, D. (2023). The financial performance of Islamic rural bank in Indonesia: A bibliometric analysis. Shirkah: Journal of Economics and Business, 8(1), 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, L., Bruni, E., & Zampieri, R. (2019). The role of leadership in a digitalized world: A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalil, M. A., Amin, M., Herjanto, H., Nourallah, M., & Öhman, P. (2023). The importance of entrepreneurial leadership in fostering bank performance. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 41(4), 926–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, M., Sarwar, N., Tariq, A., & Memon, M. A. (2024). Mastering digital leadership capabilities for business model innovation: The role of managerial decision-making and grants. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 31(3), 574–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J. (2020). The economic forces driving FinTech adoption across countries. In The technological revolution in financial services: How banks, FinTechs, and customers win together (pp. 70–89). University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M.-C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilli, K., Lettner, N., & Guettel, W. (2024). The future of leadership: New digital skills or old analog virtues? Journal of Business Strategy, 45(1), 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z. (2023). Research on the impact and development of fintech on banks. BCP Business & Management, 47, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S., Sharma, R. B., & Chouhan, V. (2022). Impact of financial technology (Fintech) on financial inclusion(FI) in rural India. Universal Journal of Accounting and Finance, 10(2), 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H. (2021). Research for the development of digital inclusive finance in rural areas of Sichuan province. Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N., & Mahakud, J. (2020). CEO characteristics and bank performance: Evidence from India. Managerial Auditing Journal, 35(8), 1057–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 38(2), 220–221. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & G. Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, R. A., Maroni, M., Satria, I., & Ariyani, N. D. (2019). The existence of regulatory sandbox to encourage the growth of financial technology in Indonesia. FIAT JUSTISIA: Jurnal Ilmu Hukum, 13(3), 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjanti, A. E., Mudiarti, H., & Hedy, B. (2021). The impact of financial technology peer-to-peer lending (P2P lending) on growth credit rural bank. Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J. L., & Vorhies, C. (2017). Leadership 2.0: The impact of technology on leadership development. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2017(153), 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, T. A. (2020). The arc of purposeful leadership. Leader to Leader, 2020(97), 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudaefi, F. A. (2020). How does Islamic fintech promote the SDGs? Qualitative evidence from Indonesia. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 12(4), 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iman, N. (2018). Memahami dinamika tekfin di Indonesia (Understanding the dynamics of fintech in Indonesia). SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriyani, E. P., Suhariadi, F., Lestari, Y. D., Aldhi, I. F., Rahmawati, E., Hardaningtyas, D., & Abbas, A. (2025). Sustaining infrastructure firm performance through strategic orientation: Competitive advantage in dynamic environments. Sustainability, 17(3), 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W., Nasir, M. H., Yousaf, Z., Khattak, A., Yasir, M., Javed, A., & Shirazi, S. H. (2022). Innovation performance in digital economy: Does digital platform capability, improvisation capability and organizational readiness really matter? European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(5), 1309–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathawala, A. M., & Sharma, V. (2021). A Study on the performance of regional rural banks in India. Research Review International Journal of Multidisciplinary, 6(11), 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharisma, D. B. (2021). Urgency of financial technology (Fintech) laws in Indonesia. International Journal of Law and Management, 63(3), 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, S., & Ho, T. C. (2019). Digital technology, digital capability and organizational performance. International Journal of Innovation Science, 11(2), 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniasari, F. (2021). The factors affecting the adoption of digital payment services using trust as mediating variable. Emerging Markets: Business and Management Studies Journal, 8(1), 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzhals, C., Graf-Vlachy, L., & König, A. (2020). Strategic leadership and technological innovation: A comprehensive review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 28(6), 437–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagna, A., & Ravishankar, M. N. (2022). Making the world a better place with fintech research. Information Systems Journal, 32(1), 61–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I., & Shin, Y. J. (2018). Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons, 61(1), 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H., Phouvong, S., & Le, P. B. (2019). How to foster innovative culture and capable champions for Chinese firms. Chinese Management Studies, 13(1), 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., & Wu, Q. (2022). Impact of management’s irrational expectations on corporate tax avoidance: A mediating effect based on level of risk-taking. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 993045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linna, F. (2021). Innovation and supervision of rural Internet Finance. E3S Web of Conferences, 253, 02088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S., Sun, C., & Chen, G. (2024). Financial technology service companies’ innovation change management and leadership-driven organizational adaptability. Journal of Social Science and Cultural Development, 1(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2012). Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing, 88(4), 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madyan, M., Harymawan, I., Minanurohman, A., & Setiawan, W. R. (2023). The impact of top management education from reputable universities on corporate capital structure: Evidence from Indonesia. Global Business Review, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]