1. Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been one of the main drivers of economic growth and plays a crucial role in both host and home countries. However, following the global financial crisis in 2008, global FDI growth began to stagnate and fell sharply in 2020 to below USD 1 trillion, representing a decline of 34.7% due to the pandemic. China’s FDI has been significantly affected as a result. By the end of September 2023, foreign firms had withdrawn a total of more than USD 160 billion from China for six consecutive quarters. This has caused the amount of FDI in China to fall into negative territory for the first time in approximately 25 years.

Following the global financial crisis, we have observed that economic policy uncertainty is a significant factor influencing FDI inflows. Governments have frequently adjusted policies to stimulate the economy, leading to an unstable policy environment and heightened macroeconomic volatility (

Colombo, 2013;

Karnizova & Li, 2014). Currently, there is limited understanding of the impact of policy environment volatility on economic activity compared to other economic factors. Previous studies have extensively explored the influence of various factors on FDI inflows, primarily focusing on long-term structural determinants. Researchers have consistently examined GDP (

L. K. Cheng & Kwan, 2000), infrastructure development (

Shah, 2014), and trade openness (

Demirhan & Masca, 2008) as the primary drivers of FDI flows. However, these traditional determinants represent relatively stable, long-term characteristics that change gradually over several years, whereas EPU, as a more dynamic, short-term factor, may fluctuate significantly within months or quarters.

Furthermore, the existing literature presents inconsistent conclusions regarding the positive or negative impact of policy-related economic uncertainty on FDI inflows. First, from the perspective of host country EPU, some scholars argue that host country EPU has a negative impact on FDI inflows (

Chen & Funke, 2011;

Pennings & Sleuwaegen, 2004). Others disagree, with researchers supporting the growth choice theory arguing that increased host country economic policy uncertainty has a positive impact on FDI inflows (

Hartman, 1972;

Oi, 1961;

Vo & Le, 2017).

Knight (

1921) argued that firms can identify and capitalize on investment opportunities to generate profits by integrating resources in an uncertain economic policy environment. Investors tend to focus on potential opportunities and returns and increase their investment efforts when uncertainty rises.

Furthermore, while previous studies have extensively examined the impact of economic policy adjustments (EPU) on macroeconomic variables and investment behavior, few have focused on the role of global EPU in influencing FDI inflows. Existing research primarily centers on single-dimensional analyses of domestic EPU, such as

Gao et al. (

2024), who specifically studied the impact of domestic EPU in 264 Chinese cities on FDI inflows;

C. H. J. Cheng (

2017) analyzed the role of domestic policy uncertainty shocks on economic fluctuations in South Korea; and

Sinha and Ghosh (

2021) studied the impact of domestic EPU on FDI inflows in India. Regarding international uncertainty, some scholars have pointed out that the impact of global EPU on local financial markets is a rarely explored angle (

Gong et al., 2023). Some studies have found that, in addition to domestic uncertainty, uncertainty in other regions/countries can also affect a country’s economic activity (e.g.,

Colombo (

2013),

Carrière-Swallow and Céspedes (

2013),

C. H. J. Cheng (

2017)). These findings suggest that international investors consider not only the host country’s EPU but also the EPU of other regions when making FDI investment decisions (

Canh et al., 2020).

Although the importance of institutional factors is increasingly recognized,

Chinh and Thi Minh Hue (

2025) found that while ‘improvements in institutional quality and financial development have a positive impact on FDI, the interaction between these two factors may produce opposite effects,’ indicating that the moderating mechanism of the joint effects of political stability and financial development remains poorly understood (

Bommadevara & Sakharkar, 2021).

Therefore, from the perspective of the host country’s EPU, related studies have not obtained consistent conclusions. We need to conduct a further systematic and comprehensive analysis to explore the impact of EPU on China’s FDI inflows. In this paper, taking China as an example, the specific research questions are as follows: (1) Whether and how world EPU affects China’s FDI? (2) Whether and how China’s EPU affects China’s FDI inflows? (3) Whether and how financial development and political stability moderate the relationship between China’s EPU and China’s FDI inflows? The specific objectives of this study are as follows: (1) To determine the impact of world EPU on China’s FDI inflows. (2) To determine the impact of China’s EPU on China’s FDI inflows. (3) To determine the moderating role of financial development and political stability on the relationship between China’s EPU and China’s FDI inflows.

This study contributes to the theory and empirical evidence in the following aspects. First, it provides insight for solving the problem of China’s continuous withdrawal of foreign capital and explaining the phenomenon of China’s declining FDI. It enriches the application of real options theory, precautionary savings theory, and financial friction theory in the Chinese context. Second, against the backdrop of high global and China’s EPU, the exploration of the moderating effects of financial development and political stability can provide insights into mitigating this phenomenon. Third, this study can provide some implications for national policymakers.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows:

Section 2 presents the findings of the relevant literature;

Section 3 describes the data sources and the empirical model;

Section 4 includes the empirical results and robustness tests; the final section presents the conclusions and implications.

5. Conclusions and Implication

This study provides a comprehensive examination of how both global and domestic economic policy uncertainty (EPU) impact China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, revealing a complex web of relationships that vary across investor characteristics and institutional contexts. Using panel data from 212 countries spanning 2009 to 2022, the multi-faceted analytical approach yields several interconnected insights that collectively paint a nuanced picture of the EPU–FDI relationship.

The baseline results consistently demonstrate that both global and China-specific EPU exert statistically significant negative influences on FDI inflows into China. The economic magnitude of these effects is substantial: a 1% increase in China’s domestic EPU corresponds to a 0.083% decrease in FDI inflows, which translates to approximately USD 116 million in lost annual investment based on China’s average FDI inflows of USD 140 billion during the study period. To contextualize this impact, a one standard deviation increase in China’s EPU (0.511) would result in potential annual losses of USD 330 million, comparable to the economic impact of a moderate trade dispute or natural disaster. This magnitude aligns with

Julio and Yook (

2016), who found that “FDI flow rate falls by approximately 13% relative to non-election years” during political uncertainty periods, and with

Liu et al. (

2021), who demonstrated that “an increase in economic policy uncertainty lowers FDI inflows” across multiple countries. These findings align with real options theory, which posits that investors delay irreversible investments when facing uncertainty, treating investment opportunities as call options that become more valuable when held rather than exercised during volatile periods. As

Bernanke (

1983) established, “when uncertainty increases, firms postpone their investment and recruitment processes,” and contemporary research confirms that “uncertainty fosters an attitude of ‘wait and see’ and therefore a postponement of decisions” in FDI contexts (

Jahn & Stricker, 2022). The Granger causality tests further confirm that EPU has predictive power over FDI flows, establishing a clear directional relationship from uncertainty to investment decisions.

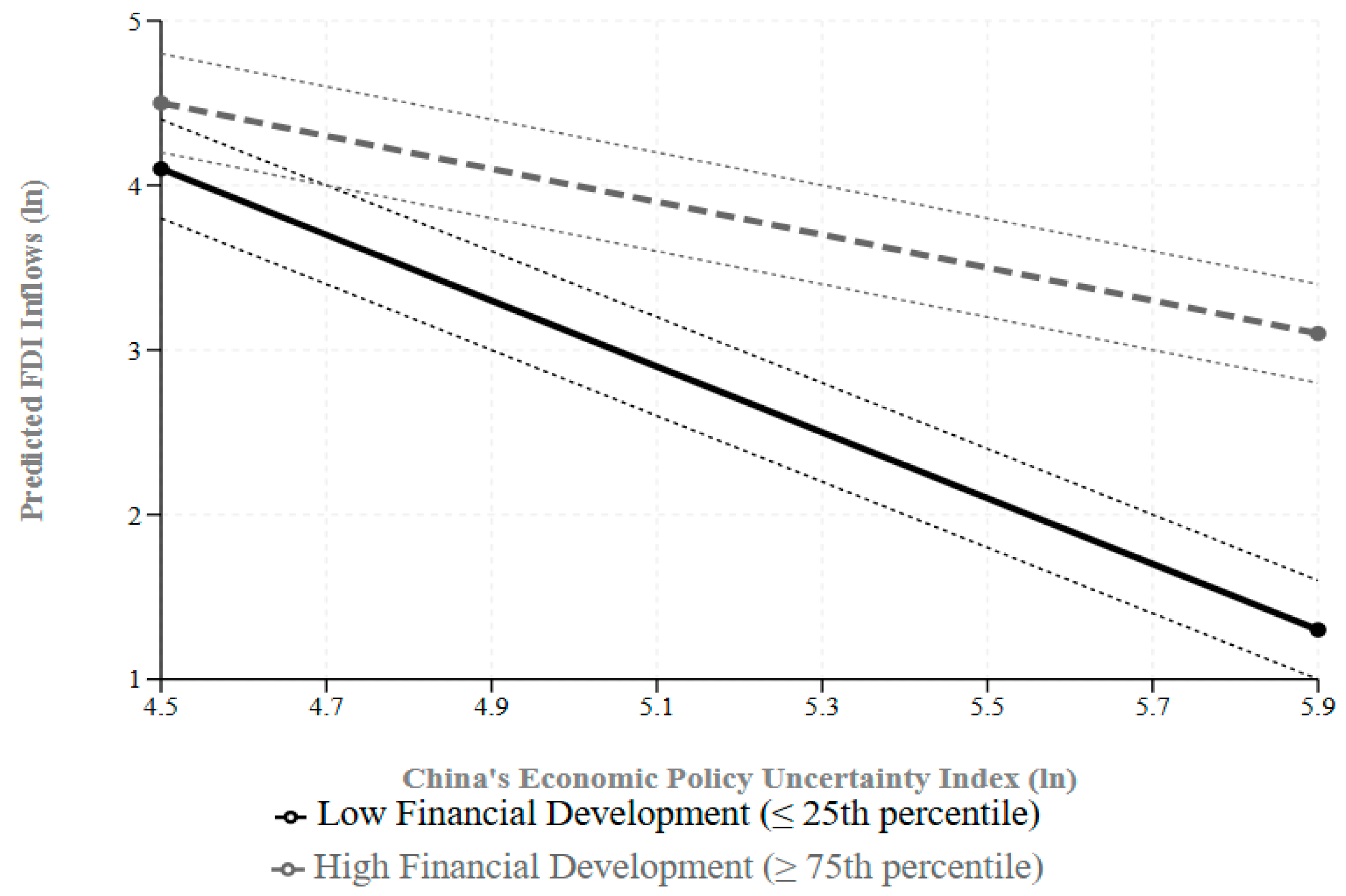

The moderating effects analysis reveals that institutional quality fundamentally alters how investors respond to policy uncertainty, with both political stability and financial development serving as powerful mitigating mechanisms. The marginal effects plots demonstrate that when political stability is high (ICRG > 9), the negative impact of EPU on FDI is reduced by approximately 60%, while strong financial development can offset up to 70% of uncertainty’s deterrent effect. These moderating mechanisms operate through distinct theoretical channels: political stability functions as a credible commitment device, signaling government dedication to maintaining investor-friendly policies regardless of short-term political pressures, while financial development reduces information asymmetries by providing sophisticated risk assessment tools and hedging instruments that enable investors to better evaluate and manage policy risks. From a behavioral economics perspective, well-developed financial markets help overcome investors’ natural loss aversion and anchoring bias by providing more accurate information processing capabilities and alternative risk management strategies.

Shin and Park (

2018) demonstrate that “sophisticated foreign investors reduce market anomaly because they are less subject to cognitive bias such as anchoring,” while recent research confirms that financial development helps investors overcome psychological biases that amplify uncertainty effects (

Marozva & Magwedere, 2025;

Zhang et al., 2023).

The heterogeneity analysis provides crucial insights into differential investor behavior and reveals the Belt and Road Initiative’s role as a “policy buffer” mechanism. The most striking finding is the 86% reduction in EPU sensitivity among BRI countries (−0.026) compared to non-BRI countries (−0.378), representing a difference of approximately USD 1.24 billion in protected annual FDI flows. This dramatic difference suggests that BRI partnerships create institutional trust frameworks that effectively insulate investment decisions from policy volatility through several mechanisms: formal diplomatic agreements that provide investment protection guarantees, regular bilateral consultation mechanisms that ensure policy predictability, and strategic economic interdependence that makes policy reversal costly for both parties. This finding is consistent with

Inada and Jinji (

2024), who found that “signing an international investment agreement stimulates FDI through a reduction in policy uncertainty,” demonstrating how “international investment agreements are one of the few policy instruments that countries can use to directly attract foreign investment.” The development status differential—where non-developed countries show ten times stronger negative responses (−0.292 vs. −0.033)—reflects varying investor risk tolerance and due diligence capabilities, with less developed economies having limited resources for comprehensive risk assessment and hedging strategies. These findings align with

Kiptoo (

2024), who emphasizes that “political stability was crucial in attracting FDI by providing a predictable and secure environment, reducing risks associated with political unrest and policy changes.” These findings have profound policy implications: countries seeking to attract investment during uncertain periods should prioritize developing formal cooperation frameworks similar to BRI partnerships, establish bilateral investment protection agreements, and create regular policy communication channels that reduce information asymmetries and build investor confidence through institutional predictability.

These three layers of analysis work together to explain the complex EPU–FDI dynamic through multiple channels: direct uncertainty effects, institutional mediation, and investor-specific risk perceptions. The baseline results establish that uncertainty generally deters investment, but the moderating effects show that this relationship can be managed through institutional development. The heterogeneity analysis then reveals that the effectiveness of these institutional buffers varies significantly across investor types. For instance, the strong moderating effect of political stability helps explain why BRI country investments are less sensitive to EPU—these strategic partnerships may serve as a form of political stability insurance.

From a policy perspective, the implications are clear:

First, predictability matters. While some level of uncertainty is inevitable in policymaking, the Chinese government—and governments in general—can reduce its adverse effects by ensuring clear communication, advance notice of reforms, and transparency in legislative processes.

Second, investments in political and institutional stability are not merely governance goals—they are also powerful economic tools. Strengthening the rule of law, regulatory coherence, and institutional efficiency can enhance investor confidence and reduce sensitivity to uncertainty.

Third, continued financial sector development—including improving credit access, reducing capital restrictions, and strengthening investor protections—can offset some of the risks posed by uncertainty. A well-functioning financial system can signal resilience and reliability, both of which are key investor priorities.

In addition, our findings highlight the interconnected nature of today’s global economy. China’s FDI inflows are not only affected by its own domestic policies but also by policy shifts and uncertainty in other parts of the world. This underscores the need for global economic cooperation and policy coordination, especially in times of geopolitical tension or economic crisis.

Finally, when uncertainty cannot be fully avoided—such as during global pandemics, political transitions, or financial shocks—governments can still mitigate its impact. As our results suggest, strengthening institutional resilience and fostering strategic international relationships (e.g., BRI partnerships) can serve as buffers to maintain foreign investor confidence.

Several limitations should be acknowledged regarding this study. The analysis relies on the EPU index developed by

Baker et al. (

2016), which, while widely accepted, may not capture all dimensions of policy uncertainty and is based primarily on English-language sources, potentially introducing bias when measuring uncertainty in non-English speaking countries. The study period (2009–2022) encompasses several major global events that may create structural breaks in the EPU–FDI relationship, and despite conducting robustness tests excluding certain periods, the possibility of regime changes in this relationship remains. The focus on FDI flows to China may limit the generalizability of findings to other emerging economies with different institutional structures, economic development levels, or geopolitical positions.

These limitations point toward several promising avenues for future research, including sector-specific analysis examining how EPU affects FDI across different industries, cross-country comparative analysis to test the generalizability of findings, and dynamic modeling to capture potential structural breaks and regime changes in the EPU–FDI relationship. Despite these limitations, this study makes important contributions to understanding the complex relationship between policy uncertainty and foreign investment, providing both theoretical insights and practical guidance for policymakers navigating an increasingly uncertain global economic environment.