Resilience, Valuation, and Governance Interactions in Shaping Financial Accounting Manipulation: Evidence from Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Construction

2.1. Financial Accounting Manipulation

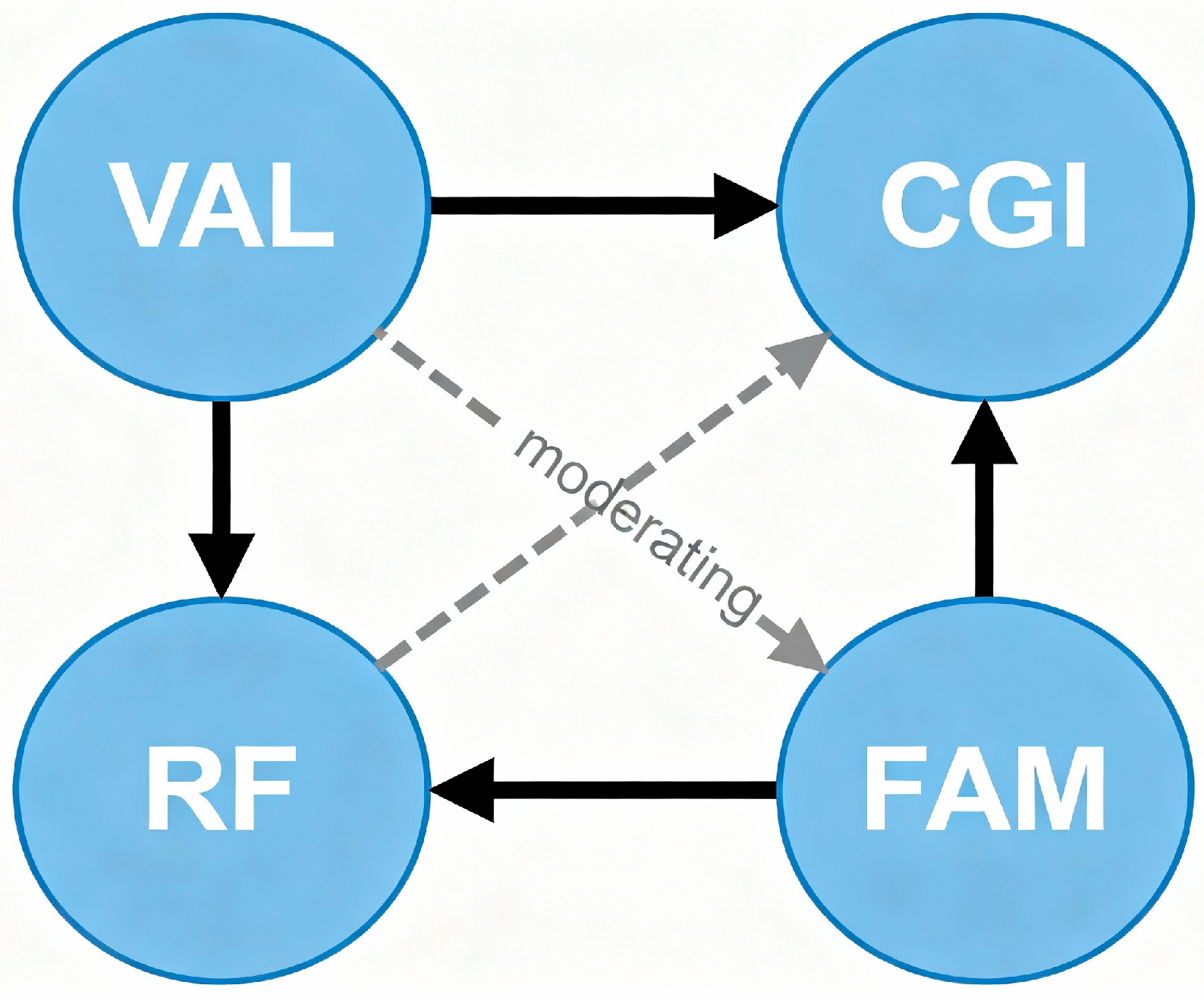

2.2. Resilience Factor, Valuation, and Country Governance

2.3. Role of Interaction Terms and Hypotheses

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Model Specification

3.2. Variable Definition and Measurement

3.3. Data Sources and Sample Construction

- (1)

- Removal of financial sector firms due to their distinct reporting structures and regulatory environments.

- (2)

- Elimination of firms with missing values required for constructing FAM (Dechow F-Score), RF proxies, and valuation ratios.

- (3)

- Screening for extreme inconsistencies and outliers before winsorization.

- (4)

- Harmonization of industry classification using GICS and regional grouping following World Bank regional definitions.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Pairwise Correlation

4.2. Heterogeneity Character and Endogeneity Test

4.3. Baseline Model

4.4. Robustness Check

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alharbi, S., Al Mamun, M., & Atawnah, N. (2021). Uncovering real earnings management: Pay attention to risk-taking behavior. International Journal of Financial Studies, 9(4), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H., Amin, H. M. G., Mostafa, D., & Mohamed, E. K. A. (2022). Earnings management and investor protection during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from G-12 countries. Managerial Auditing Journal, 37(8), 951–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. I. (1968). Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance, 23(4), 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, A. M., Azimli, A., & Adedokun, M. W. (2025). Earnings management and IFRS adoption influence on corporate sustainability performance: The moderating roles of institutional ownership and board independence. Sustainability, 17, 7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A., Candy, C., & Robin, R. (2022). Detecting fraudulent financial statements using fraud s.c.o.r.e model and financial distress. International Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting Research, 6(1), 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baigon, T. E., Amanova, G., & Saparbaeva, S. S. (2024). Exploring the impact of financial statement manipulations on stakeholders. Vestnik Torajgyrov Universiteta, 2, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, C. F., Schaffer, M. E., & Stillman, S. (2007). Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/GMM estimation and testing. The Stata Journal, 7(4), 465–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benuzzi, M., Bax, K., Paterlini, S., & Taufer, E. (2023). Chasing ESG performance: How methodologies shape outcomes. International Review of Financial Analysis, 104, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, A., Wang, Y., Ntim, C. G., & Glaister, K. W. (2021). National culture, corporate governance and corruption: A cross-country analysis. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(3), 3852–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortomeu, J., Cheynel, E., Li, E. X., & Liang, Y. (2021). How pervasive is earnings management? Evidence from a structural model. Management Science, 67(8), 5145–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, T. S. (1978). Testing for autocorrelation in dynamic linear models. Australian Economic Papers, 17(31), 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T. H. (2024). Past, present, and future of earnings management research. Cogent Business & Management, 11, 2300517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capital markets and key sustainability issues in Asia. (2023). Corporate Governance. [CrossRef]

- Carmona, S., Filatotchev, I., Fisch, J. H., & Livne, G. (2023). Integrating contemporary accounting and international business research: Progress so far and opportunities for the future. Accounting and Business Research, 54(4), 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casquel Júnior, F. L., Gaio, L. E., Belli, M. M., Dos Santos, L. H., & Povedano, R. (2023). ESG index impact on the performance of education sector companies. Bohrium Research Repository, 17(2), e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A. H., & Wu, R. Y. (2022). Mediating effect of brand image and satisfaction on loyalty through experiential marketing: A case study of a sugar heritage destination. Sustainability, 14(12), 7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Cheng, C. S. A., Li, S., & Zhao, J. (2021). The monitoring role of the media: Evidence from earnings management. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 48(3–4), 533–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.-M., Kim, H. J., Mun, S., & Han, S. H. (2021). Do confident CEOs increase firm value under competitive pressure? Applied Economics Letters, 28(17), 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, A. (1987). Equity risk, the opportunity set, production costs, and debt [Working paper]. University of Rochester. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysikou, K., & Kapetanios, G. (2024). Heterogeneous grouping structures in panel data. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtaoui, A. (2024). The manipulation of financial statements: A theoretical explanation. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(4), 3218–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J., Dechow, P. M., Hui, K. W., & Wang, A. Y. (2019). Maintaining a reputation for consistently beating earnings expectations and the slippery slope to earnings manipulation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(4), 1966–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D. J., Ji, S., Peter, R., & Tarsalewska, M. (2020). Market manipulation and innovation. Journal of Banking and Finance, 120, 105957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P. M., Ge, W., Larson, C. R., & Sloan, R. G. (2011). Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(1), 17–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiraj, R., Demiraj, E., & Dsouza, S. (2025). The moderating role of worldwide governance indicators on ESG–firm performance relationship: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(4), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W., Levine, R., Lin, C., & Xie, W. (2021). Corporate immunity to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Financial Economics, 141(2), 802–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Jardin, P., Veganzones, D., & Séverin, E. (2019). Forecasting corporate bankruptcy using accrual-based models. Computational Economics, 54(1), 7–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C., & Pescetto, G. (2019). Overvaluation and earnings management: Does the degree of overvaluation matter? Accounting and Business Research, 49(2), 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H. K., Kang, H., & Salter, S. B. (2022). The joint effect of internal and external governance on earnings management and firm performance. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 33(2), 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckles, D. L. (2021). Asymmetry in earnings management surrounding targeted ratings. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The cross-section of expected stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassas, A., Nerantzidis, M., Tsakalos, I., & Asimakopoulos, I. (2023). Earnings quality and firm valuation: Evidence from several European countries. Corporate Governance, 23(6), 1298–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J., LaFond, R., Olsson, P. M., & Schipper, K. (2005). The market pricing of accruals quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(2), 295–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B., & Dodd, D. L. (1934). Security analysis. McGraw–Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, J. (1998). A new bankruptcy prediction model for U.S. firms. Journal of Management and Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, L. P. (1982). Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica, 50(4), 1029–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., & Ke, B. (2021). How does reduced timeliness of public enforcement affect corporate disclosure behavior in a developing financial market? SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Li, X., & Wei, K. C. J. (2021). Investor protection and resource allocation: International evidence. International Review of Economics & Finance, 75, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikpere, C. O., & Aronu, C. O. (2024). Improved two-stage least square estimation with permutation methods for solving endogeneity problems. Earthline Journal of Mathematical Sciences, 14(6), 1213–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, Z. A., Wong, W. C., & Binti Ismail, R. (2022). Governance quality and momentum returns: International evidence. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 41(1), 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido-Lobatón, P. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. World Bank working paper 5430. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettering, C. (2023). Hypothesis development. In The Effect of COVID-19 on loan loss provisions and earnings management of European banks. BesMasters. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, D. D. (2021). Innovation, short-termism, and the cost of strong corporate governance. Strategic Management Journal, 42(1), 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, S. F. A. (2024). An assessment of methods to deal with endogeneity in corporate governance and reporting research. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 25(3), 606–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. (2024). ESG activities and value relevance: Break down the market-to-book ratio into growth opportunities and misvaluation measures. Korean Management Review, 53(1), 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-W. R., & Shawn, H. (2022). Conservative financial reporting and resilience to the financial crisis. Sustainability, 14(14), 8535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviet, J. F., & Kripfganz, S. (2021). Instrument approval by the Sargan test and its consequences for coefficient estimation. Economics Letters, 205, 109935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, S. P., Mizik, N., & Roychowdhury, S. (2016). Managing for the moment: The role of earnings management via real activities versus accruals in SEO valuation. The Accounting Review, 91(2), 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovjanić, M. (2020). Fraudulent financial reporting as a permanent problem for decision makers. Available online: https://portal.finiz.singidunum.ac.rs/Media/files/2020/73-77.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wang, X., & Xu, F. (2024). Survive the economic downturn: Operating flexibility, productivity, and stock crash. Journal of Operations Management, 71(4), 483–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, W. (2024). Beyond the barriers: Institutional strength as a shield in curbing earnings manipulation. Available online: https://www.qeios.com/read/33ZFSO (accessed on 28 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Martens, W., & Andersson, D. E. (2024). From M-score to F-score: Moderating the relationship between earnings management and stock performance. Available online: https://www.qeios.com/read/RI1NIL/pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Meng, T., Zhang, T., Chen, M., & Cao, J. (2023). Factors influencing enterprise organizational resilience: Evidence based on machine learning. Managerial and Decision Economics, 45(2), 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, E., & Paolucci, G. (2023). ESG dimensions and bank performance: An empirical investigation in Italy. Corporate Governance, 23(3), 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mos, C. (2024). Determinants of financial reporting quality: A review of existing literature. Review of Economic Studies and Research “Virgil Madgearu”, 17(2), 101–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S. C. (1977). Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics, 5(2), 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, P. M. D. C., & Smith, R. (2017). Tests of additional conditional moment restrictions. Journal of Econometrics, 200(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. H. (2025). Effects of COVID-19 on financial reporting in the U.S. life science industry. Journal of Accounting and Finance, 25(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddika, A., & Sarwar, A. (2023). The evolution of corporate governance in Asian markets. In Cases on uncovering corporate governance challenges in Asian markets. IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney, M. T., & Liao, G. (2025). Greenwashing, environmental performance, and financial outcome through panel VAR/GMM analysis. Sustainability, 17(9), 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J. H., & Yogo, M. (2005). Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In D. W. K. Andrews, & J. H. Stock (Eds.), Identification and inference for econometric models (pp. 80–108). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J. H., Warkentin, M., & Wallace, L. (2021). So many ways for assessing outliers: What really works and does it matter? Journal of Business Research, 132, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synn, C., & Williams, C. D. (2023). Financial reporting quality and optimal capital structure. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 51(5–6), 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, H., & Polat, A. (2021). Is leverage a substitute or outcome for governance? Evidence from financial crises. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(4), 1007–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulcanaza-Prieto, A. B., & Lee, Y. (2022). Real earnings management, firm value, and corporate governance: Evidence from the Korean market. International Journal of Financial Studies, 10(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-F., Kim, Y., Kim, S., & Song, K. (2024). Refinancing risk, earnings management, and stock return. Research in International Business and Finance, 70, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintoki, M. B., Linck, J. S., & Netter, J. M. (2012). Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 105(3), 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, D., Czapiewski, L., & Lizińska, J. (2024). Company financial distress and earnings manipulation. In Earnings management and corporate finance. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd ed.). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H., Shi, W., Xia, J., & Liu, M. (2023). M-score and F-score from the financial statement for company fraud prediction. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences, 19(1), 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W. (2020). Costly regulatory institutions of enforcement, extent of the market, and rational expectations. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Liu, Z., Wang, H., Zhang, X., & Zheng, X. (2022). How does COVID-19 affect earnings management: Empirical evidence from China. Research in International Business and Finance, 63, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zattoni, A., Dedoulis, E., Leventis, S., & van Ees, H. (2020). Corporate governance and institutions—A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 28(6), 465–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Li, H., & Liu, J. (2024). How does ESG constrain corporate earnings management? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 64, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition of Variables | Proxy/Description | Reference and Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Accounting Manipulation (FAM) | The practice of companies changing or engineering financial reports to make them look better than the actual conditions. | References: Dechow et al. (2011). Sources: Refinitiv Eikon | |

| Stock Market Valuation (VAL) | Market valuation of a company, usually measured by financial ratios such as Price-to-Earnings (PE) or Price-to-Book (PB). | References: Graham and Dodd (1934). Fama and French (1992). Sources: Refinitiv Eikon | |

| Resilience Factor (RF) | A measure of a company’s financial resilience to the risk of bankruptcy, for example, using the Altman Z-score or Grover Model. | References: Altman (1968) Grover (1998) Sources: Refinitiv Eikon | |

| Country Governance Index (CGI) | World bank Country Governance Indicators | Worldwide Governance Indicator (WGI) developed by Kaufmann et al. (2010). (Voice and Accountability, Political Stability, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption) | Reference: Kaufmann et al. (2010) Source: Website World Bank (www.worldbank.org, 28 October 2025) |

| Interaction Term 1 (RF × VAL) | The interaction between a company’s financial resilience and market valuation. | Sources: Refinitiv Eikon | |

| Interaction Term 2 (VAL × CGI) | The interaction between market valuation and the quality of state governance. | Sources: Refinitiv Eikon | |

| Interaction Term 3 (RF × CGI) | The interaction between corporate financial resilience and the quality of state governance. | Sources: Refinitiv Eikon | |

| Debt to Equity Ratio (DER) | The debt-to-equity ratio indicates the company’s funding structure. | References: Myers (1977) Sources: Refinitiv Eikon | |

| Firm Size (SIZE) | Company size, generally proxied by the logarithm of total assets. | References: Christie (1987) Sources: Refinitiv Eikon |

| Industry | Freq. | Percent | Cum. | Regions | Freq. | Percent | Cum. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy and Utilities | 1236 | 2.39 | 2.39 | East Asia | 25,164 | 48.73 | 48.73 |

| Industry and Infrastructure | 12,024 | 23.29 | 25.68 | Southeast Asia | 15,984 | 30.96 | 79.69 |

| Consumer and Lifestyle | 26,472 | 51.27 | 76.95 | South Asia | 6240 | 12.08 | 91.77 |

| Service and Communication | 3348 | 6.48 | 83.43 | West Asia | 4248 | 8.23 | 100 |

| Property and Natural Resources | 8556 | 16.57 | 100 | ||||

| Total | 51,636 | 100 | Total | 51,636 | 100 |

| Stats | FAM | VAL1 | VAL2 | RF1 | RF2 | CGI | DER | SIZE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | −3.396 | 6.650 | 1.523 | 4.834 | 1.598 | 0.258 | 1.162 | 18.855 |

| p50 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.018 | 3.515 | 0.814 | −0.107 | 0.820 | 18.725 |

| SD | 37.212 | 12.427 | 1.409 | 4.347 | 1.797 | 0.673 | 1.061 | 1.962 |

| Min | −97.884 | −1.511 | 0.186 | 0.141 | −0.306 | −1.162 | 0.089 | 7.048 |

| Max | 65.370 | 44.573 | 5.612 | 17.377 | 5.814 | 1.628 | 4.055 | 26.700 |

| p5 | −97.884 | −1.511 | 0.186 | 0.141 | −0.306 | −0.527 | 0.089 | 15.874 |

| p95 | 65.370 | 44.573 | 5.612 | 17.377 | 5.814 | 1.323 | 4.055 | 22.303 |

| N | 50,777 | 51,547 | 51,547 | 51,633 | 51,636 | 51,636 | 51,636 | 51,636 |

| VAL1 | VAL2 | RF1 | RF2 | CGI | DER | SIZE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAL1 | 1 | ||||||

| VAL2 | 0.275 | 1 | |||||

| RF1 | 0.075 | 0.322 | 1 | ||||

| RF2 | −0.060 | 0.006 | 0.641 | 1 | |||

| CGI | 0.094 | −0.035 | −0.213 | −0.477 | 1 | ||

| DER | −0.040 | 0.072 | −0.385 | −0.182 | −0.077 | 1 | |

| SIZE | 0.342 | −0.025 | −0.167 | −0.158 | 0.203 | 0.178 | 1 |

| Variable | OLS | FE | RE |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAL1 | 0.100 *** (0.021) | 0.104 *** (0.029) | 0.100 *** (0.023) |

| RF1 | 0.275 *** (0.052) | 0.297 *** (0.069) | 0.275 *** (0.048) |

| CGI | −2.222 *** (0.403) | 38.14 *** (1.813) | −2.222 *** (0.402) |

| DER | −0.999 *** (0.187) | −2.245 *** (0.293) | −0.999 *** (0.174) |

| SIZE | 1.777 *** (0.098) | 12.08 *** (0.369) | 1.777 *** (0.095) |

| VAL1 × CGI | −0.028 (0.018) | −0.000 (0.027) | −0.028 (0.020) |

| RF1 × CGI | 0.221 *** (0.065) | −0.161 (0.101) | 0.221 *** (0.063) |

| VAL1 × RF1 | −0.00564 ** (0.003) | −0.001 (0.00365) | −0.00564 ** (0.003) |

| Constant | −37.06 *** (1.903) | −240.4 *** (6.858) | −37.06 *** (1.763) |

| FE Test | 0.91 | ||

| RE Test | 0.32 | ||

| Auto | 1.148 | ||

| Heterogeneity | 345.55 *** | ||

| Endogeneity | 22.412 *** | ||

| Observations | 50,689 | 50,689 | 50,689 |

| R-squared | 0.011 | 0.041 |

| Variable | Coefficient |

|---|---|

| RF1 | 0.546 *** |

| (0.097) | |

| VAL1 | −0.129 ** |

| (0.060) | |

| CGI | −1.060 ** |

| (0.450) | |

| DER | 0.064 |

| (0.230) | |

| SIZE | 1.832 *** |

| (0.128) | |

| RF1 × VAL1 | 0.009 |

| (0.006) | |

| VAL1 × CGI | 0.061 ** |

| (0.027) | |

| RF1 × CGI | 0.005 |

| (0.071) | |

| Constant | −34.27 *** |

| (2.419) | |

| Over-id Test | 5.24 |

| Under-id Test | 1342.048 *** |

| F Stat | 42.99 *** |

| Observations | 38,617 |

| R-squared | 0.007 |

| VARIABLES | Baseline | FAM-RF1-VAL2 | FAM-RF2-VAL1 | FAM-RF2-VAL2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF# | 0.546 *** | 0.413 *** | 1.654 *** | 2.709 *** |

| (0.097) | (0.112) | (0.278) | (0.340) | |

| VAL# | −0.129 ** | 0.495 * | −0.001 | 2.332 *** |

| (0.060) | (0.300) | (0.0310) | (0.414) | |

| CGI | −1.060 ** | −1.584 *** | −1.592 *** | 0.301 |

| (0.450) | (0.478) | (0.451) | (0.580) | |

| DER | 0.064 | −0.107 | −0.122 | −0.354 * |

| (0.230) | (0.258) | (0.205) | (0.194) | |

| SIZE | 1.832 *** | 1.648 *** | 1.629 *** | 1.645 *** |

| (0.128) | (0.098) | (0.124) | (0.097) | |

| RF * × VAL * | 0.009 | 0.203 * | 0.194 ** | −0.528 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.108) | (0.085) | (0.159) | |

| VAL * × CGI | 0.061 ** | 0.165 | 0.527 *** | −0.719 ** |

| (0.027) | (0.256) | (0.201) | (0.306) | |

| RF * × CGI | 0.005 | 0.829 *** | 1.713 *** | 1.744 *** |

| (0.071) | (0.243) | (0.267) | (0.263) | |

| Constant | −34.27 *** | −31.42 *** | −30.82 *** | −34.46 *** |

| (2.419) | (2.079) | (2.229) | (2.056) | |

| Over-id Test | 5.24 | 25.421 | 14.314 | 11.403 |

| Under-id Test | 1342.048 *** | 3097.409 *** | 3233.547 *** | 3162.18 *** |

| F Stat | 42.99 *** | 56.99 *** | 58.22 *** | 62.53 *** |

| Observations | 38,617 | 38,617 | 38,621 | 38,621 |

| R-squared | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.013 |

| Variable | Baseline | East Asia | Southeast Asia | South Asia | West Asia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF1 | 0.546 *** | 2.340 *** | 0.840 *** | 1.813 *** | −1.266 ** |

| (0.097) | (0.632) | (0.199) | (0.359) | (0.543) | |

| VAL1 | −0.129 ** | −0.019 | −0.274 ** | −0.278 * | −0.973 *** |

| (0.060) | (0.127) | (0.112) | (0.167) | (0.260) | |

| CGI | −1.060 ** | 2.771 | −3.783 ** | −12.01 *** | 14.06 *** |

| (0.450) | (2.409) | (1.491) | (3.630) | (4.471) | |

| DER | 0.064 | −0.492 | 0.670 | 1.366 ** | −0.507 |

| (0.230) | (0.372) | (0.408) | (0.551) | (0.881) | |

| SIZE | 1.832 *** | 1.412 *** | 2.098 *** | 1.478 *** | 3.259 *** |

| (0.128) | (0.187) | (0.222) | (0.325) | (0.512) | |

| RF1 × VAL1 | 0.009 | −0.008 | 0.012 | −0.010 | 0.130 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.0107) | (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.030) | |

| VAL1 × CGI | 0.061 ** | 0.0859 | −0.003 | −0.662 ** | −0.278 |

| (0.027) | (0.0837) | (0.052) | (0.269) | (0.204) | |

| RF1 × CGI | 0.005 | −1.855 *** | 0.713 ** | 2.967 *** | −2.678 *** |

| (0.071) | (0.536) | (0.284) | (0.633) | (0.689) | |

| Constant | −34.27 *** | −29.59 *** | −40.25 *** | −35.83 *** | −52.05 *** |

| (2.419) | (5.170) | (4.031) | (6.004) | (8.812) | |

| Over-id Test | 5.24 | 11.994 | 4.222 | 6.303 | 3.925 |

| Under-id Test | 1342.048 *** | 464.278 *** | 325.298 *** | 197.103 *** | 161.23 *** |

| F Stat | 42.99 *** | 22.82 *** | 15.84 *** | 6.64 *** | 9.9 *** |

| Observations | 38,617 | 18,802 | 11,958 | 4675 | 3182 |

| R-squared | 0.007 | −0.005 | 0.005 | −0.026 | −0.007 |

| Variable | Baseline | Energy and Utilities | Industry and Infrastructure | Consumer and Lifestyle | Service and Communication | Property and Natural Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF1 | 0.546 *** | 1.641 | 0.229 | 0.410 ** | 0.349 | 4.626 *** |

| (0.097) | (1.466) | (0.249) | (0.175) | (0.776) | (1.136) | |

| VAL1 | −0.129 ** | −0.029 | −0.250 ** | −0.223 * | −0.044 | −2.090 |

| (0.060) | (0.356) | (0.111) | (0.134) | (0.274) | (1.734) | |

| CGI | −1.060 ** | −2.030 | 0.467 | −1.479 | −4.173 | −54.89 *** |

| (0.450) | (3.121) | (1.316) | (1.080) | (2.696) | (18.31) | |

| DER | 0.064 | 0.969 | 0.184 | −0.904 ** | 0.105 | 1.456 *** |

| (0.230) | (1.271) | (0.433) | (0.362) | (0.824) | (0.520) | |

| SIZE | 1.832 *** | 1.395 * | 2.372 *** | 1.444 *** | 0.947 *** | 2.512 *** |

| (0.128) | (0.750) | (0.268) | (0.190) | (0.338) | (0.356) | |

| RF1 × VAL1 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.031 ** | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.015 |

| (0.006) | (0.076) | (0.013) | (0.011) | (0.029) | (0.049) | |

| VAL1 × CGI | 0.061 ** | −0.122 | −0.124 ** | 0.186 ** | 0.048 | −5.319 |

| (0.027) | (0.112) | (0.058) | (0.075) | (0.111) | (4.452) | |

| RF1 × CGI | 0.005 | 0.970 | 0.031 | −0.184 | 0.079 | 11.41 *** |

| (0.071) | (1.493) | (0.290) | (0.119) | (0.292) | (3.144) | |

| Constant | −34.27 *** | −32.04 * | −43.30 *** | −24.44 *** | −13.51 * | −66.92 *** |

| (2.419) | (19.13) | (4.929) | (3.601) | (8.006) | (9.192) | |

| Over-id Test | 5.24 | 2.176 | 6.476 | 3.428 | 12.845 | 9.069 |

| Under-id Test | 1342.048 *** | 33.532 *** | 487.221 *** | 405.555 *** | 91.148 *** | 9.193 *** |

| F Stat | 42.99 *** | 1.27 *** | 15.3 *** | 14.69 *** | 6.27 *** | 10.67 *** |

| Observations | 38,617 | 927 | 9008 | 19,785 | 2510 | 6387 |

| R-squared | 0.007 | −0.034 | 0.016 | 0.003 | 0.015 | −0.044 |

| Variable | Baseline | COVID-19 | Non-COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF1 | 0.546 *** | 0.848 *** | 0.167 |

| (0.097) | (0.130) | (0.147) | |

| VAL1 | −0.129 ** | −0.035 | −0.245 *** |

| (0.060) | (0.078) | (0.088) | |

| CGI | −1.060 ** | 0.457 | −3.350 *** |

| (0.450) | (0.562) | (0.746) | |

| DER | 0.064 | 0.713 ** | −0.861 ** |

| (0.230) | (0.297) | (0.362) | |

| SIZE | 1.832 *** | 1.656 *** | 2.134 *** |

| (0.128) | (0.162) | (0.207) | |

| RF1 × VAL1 | 0.009 | −0.004 | 0.025 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| VAL1 × CGI | 0.061 ** | 0.0382 | 0.098 ** |

| (0.027) | (0.036) | (0.040) | |

| RF1 × CGI | 0.005 | −0.109 | 0.172 |

| (0.071) | (0.093) | (0.110) | |

| Constant | −34.27 *** | −34.30 *** | −35.45 *** |

| (2.419) | (3.045) | (3.933) | |

| Over-id Test | 5.24 | 4.163 | 4.459 |

| Under-id Test | 1342.048 *** | 709.029 *** | 672.537 *** |

| F Stat | 42.99 *** | 24.17 *** | 23.43 *** |

| Observations | 38,617 | 21,473 | 17,144 |

| R-squared | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wibowo, J.C.; Ariefianto, M.D.; Laurence, L.; Soepriyanto, G. Resilience, Valuation, and Governance Interactions in Shaping Financial Accounting Manipulation: Evidence from Asia. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120719

Wibowo JC, Ariefianto MD, Laurence L, Soepriyanto G. Resilience, Valuation, and Governance Interactions in Shaping Financial Accounting Manipulation: Evidence from Asia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):719. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120719

Chicago/Turabian StyleWibowo, Janet Claresta, Moch. Doddy Ariefianto, Lizvin Laurence, and Gatot Soepriyanto. 2025. "Resilience, Valuation, and Governance Interactions in Shaping Financial Accounting Manipulation: Evidence from Asia" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120719

APA StyleWibowo, J. C., Ariefianto, M. D., Laurence, L., & Soepriyanto, G. (2025). Resilience, Valuation, and Governance Interactions in Shaping Financial Accounting Manipulation: Evidence from Asia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120719