3.1. Hypotheses and Methodology

The main question of interest I examine is the following: Does an increase in CEO risk-taking decrease firm sustainability as proxied by ESG measures? If fWHR is our measure of risk-taking, this suggests the following hypothesis:

H1. An increase in fWHR will decrease firm sustainability as measured by ESG ratings.

While I initially measure sustainability using the total ESG ratings, sub-hypotheses look at the effects of risk-taking on the individual measures of E, S, and G. In all cases, the proposition is that an increase in the risk-taking measure, fWHR, will decrease the individual sustainability gauge.

Sustainability might also be thought of as a destination, rather than a journey. A change in a company’s CEO affords a new direction for the firm that might include adopting more sustainable practices. This suggests a second set of related hypotheses that investigates episodes of CEO turnover. The second proposition is as follows:

H2. A change in a firm’s CEO will increase sustainability as measured by ESG more than at a similar firm that does not experience CEO turnover.

Additionally, embracing sustainable practices is likely a “sticky” policy. It is hard to imagine that firms adopting renewable energy, enforcing socially responsible supply chain agreements, or implementing environmentally friendly manufacturing processes will suddenly backtrack and return to previous procedures. If true, advancing sustainability suggests an asymmetry when there is CEO turnover, and a final testable hypothesis is as follows:

H2a. CEO turnover from a less risk-taking to a more risk-taking executive has no relative effect on sustainable ESG measures, whereas a change in CEO from a more risk-taking to a less risk-taking executive will comparatively increase the firm’s sustainable practices.

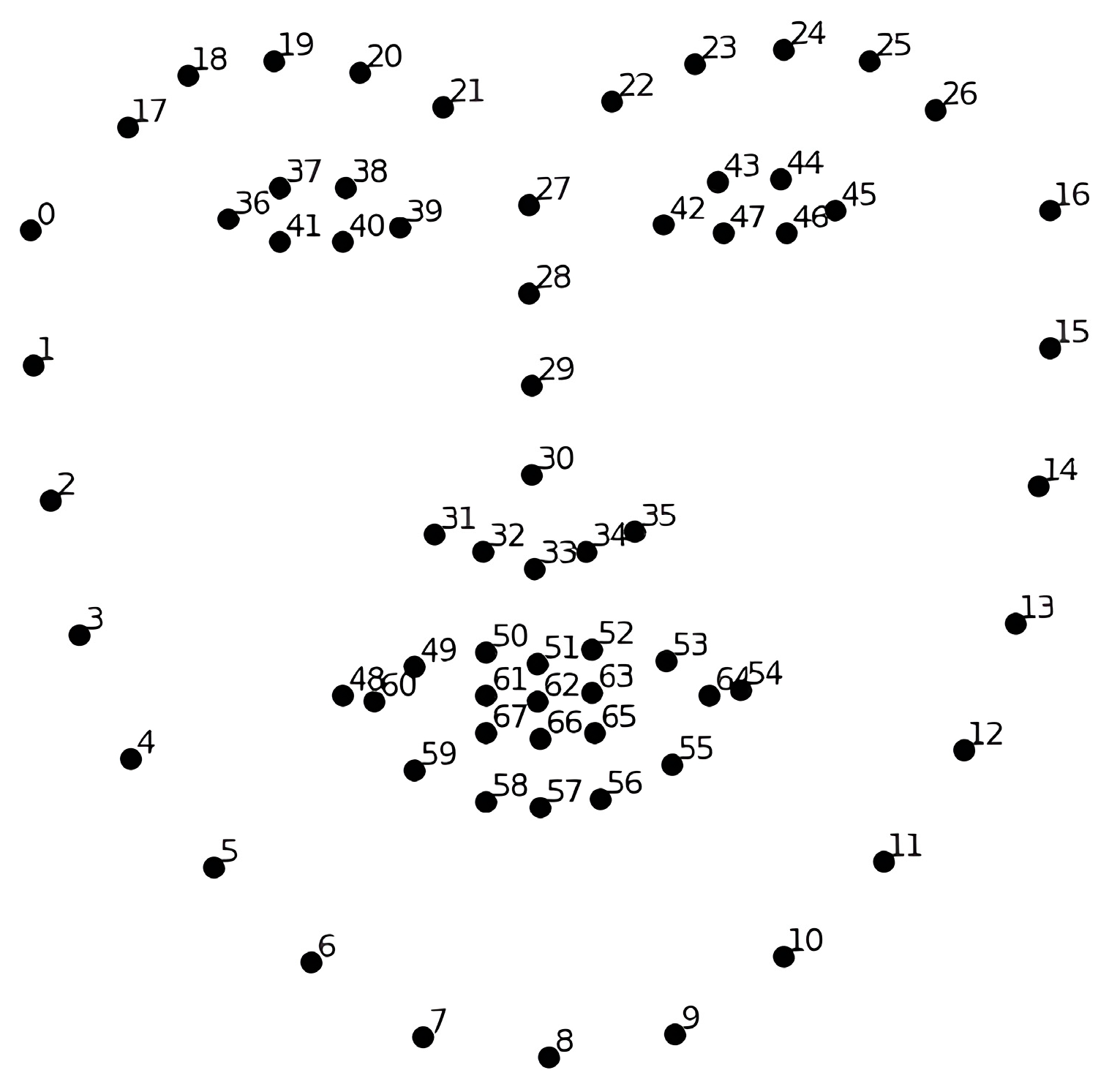

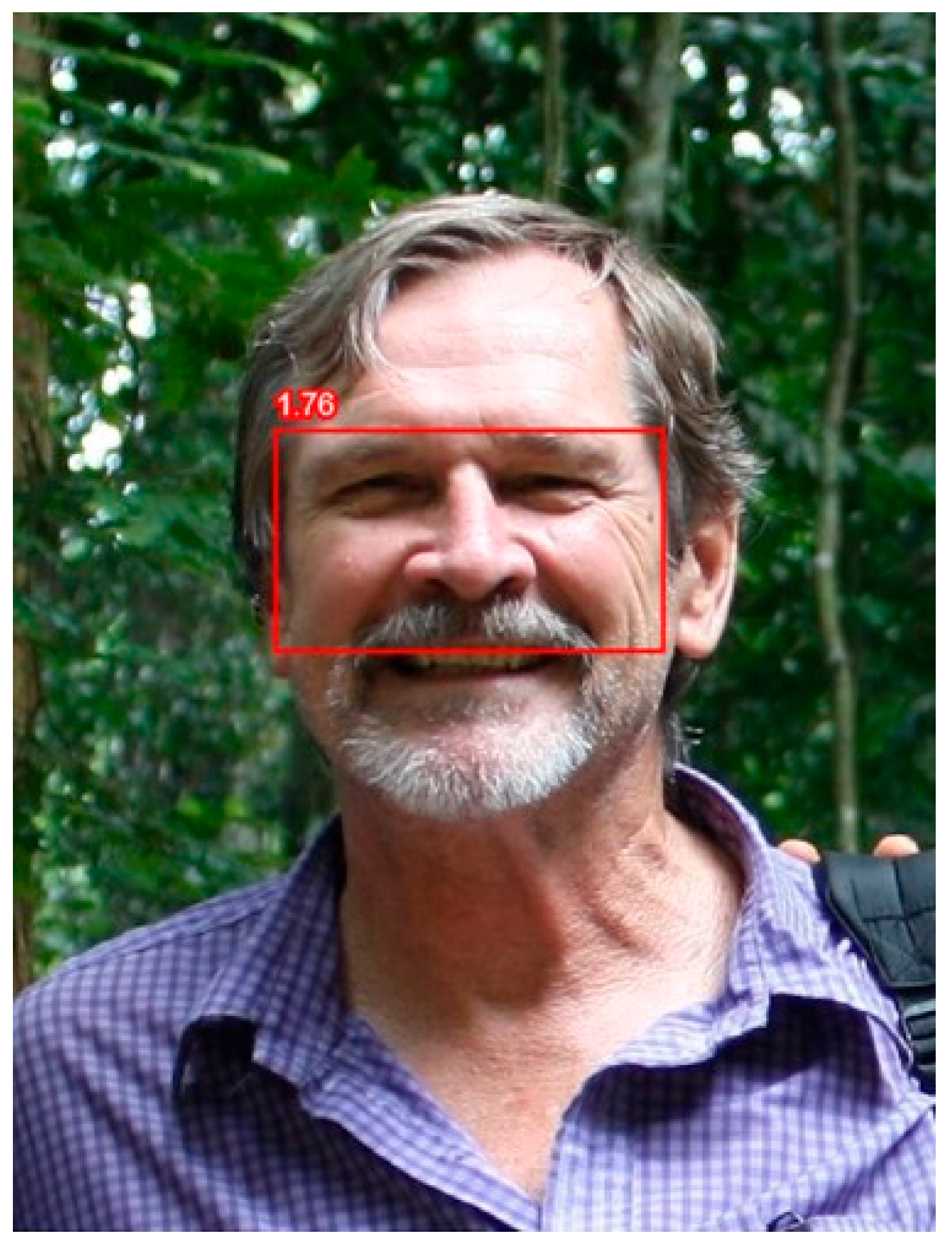

In examining the effects of CEO characteristics on firm sustainability, the main trait of interest is executive risk-taking. I consider a direct path that stems from higher testosterone, which is believed to produce aggression and risk-taking behavior. An executive’s fWHR proxies for their testosterone levels. As risk-taking has been found to be positively related to testosterone levels, fWHR serves as a measure of executive risk-taking. I have gathered a collection of CEO photos from Annual Reports, LinkedIn, and other public sources of company information.

3.3. Structural Equation for a Test of Hypothesis 1

The main test of the first hypothesis employs multiple regression analysis and follows the general form of

Kamiya et al. (

2019):

where SUSTAIN is an ESG measure of sustainability for firm i, RiskTake is a risk-taking metric associated with the chief executive officer, CEO is a vector of CEO characteristics including age, gender, and cash compensation, FIRM is a vector of firm characteristics such as size (assets), leverage, and profitability, FE equals year and industry fixed effects, and ϵ is an error term. There is a lead-lag effect, so that the independent variables in year t influence the firm’s sustainability measure in t + 1. Thus, the model implies that CEO and firm characteristics affect next year’s sustainability measure.

For the main measure of risk-taking, the analysis uses the CEO’s fWHR. Thus, a test of Hypothesis 1 examines the sign of the coefficient, b. A greater fWHR implies greater risk-taking, so the main hypothesis predicts that the RiskTake coefficient, b, will be negative, holding all else constant. Thus, an increase in CEO risk-taking decreases the sustainability of the firm.

3.4. Tests for Hypotheses 2 and 2a

To test Hypothesis 2, I first identify all firms that had CEO turnover within the sample period of analysis. I then randomly match the company with another firm in the same industry that did not experience a change in CEO that year. Having already identified the industry and fiscal year, there frequently remains only a small group of potential matching firms. Thus, I use a random selection process rather than some machine learning algorithm that would require a larger potential data set.

To see if a new CEO produces an increase in firm sustainability over the following year above what you would expect, the analysis compares the change in sustainability over the year following CEO turnover to the change in sustainability of the matching firm. To formally test Hypothesis 2, I then run a matched pair t-test comparing changes in ESG, our measure of sustainability.

Hypothesis 2a predicts an asymmetric response to firm sustainability when there is CEO turnover. Specifically, a change from a less risk-taking to a more risk-taking executive will have no relative effect on sustainable measures, while a CEO switch from a more risk-taking to a less risk-taking individual will increase the firm’s sustainable practices. To test this hypothesis, the analysis separates CEOs according to their fWHR.

Group 1 is the upper quartile of fWHR values, group 2 is the interquartile, and group 3 is the lower quartile. If the new CEO is in a higher fWHR group than the former CEO, i.e., a sign of more aggressive, risk-taking behavior, they are subsequently matched with a firm that has no CEO turnover for the year. Following Hypothesis 2a, a matched pair t-test is then run to see if there are any differences in firm sustainability.

Similarly, when the new CEO is in a lower fWHR group than their predecessor, they are again compared to a control group to see the relative change in sustainability. According to Hypothesis 2a, there should be little or no difference in sustainability in the first case, whereas the second case predicts a higher relative change in ESG.

3.5. Data

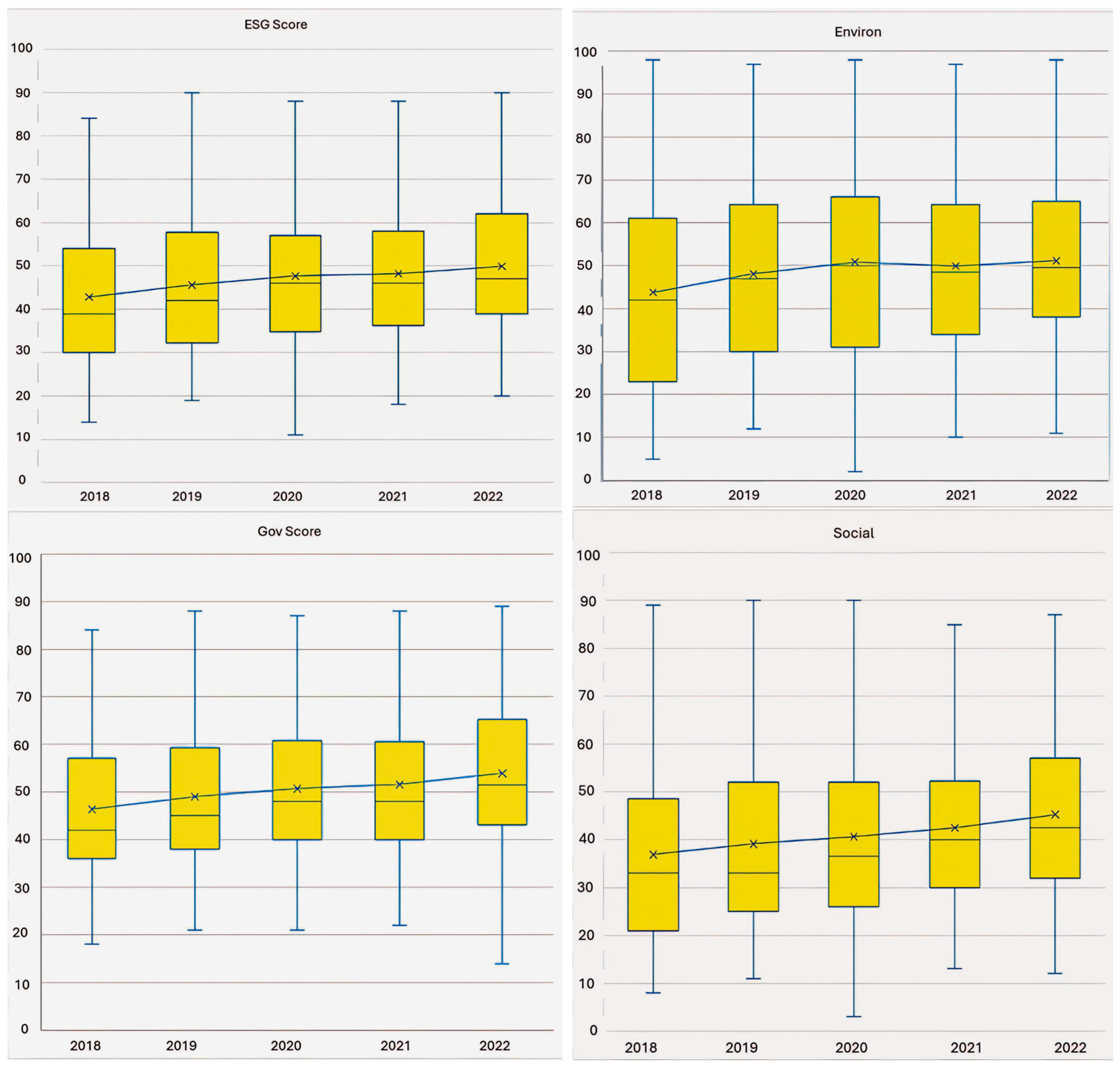

The estimation of the first set of regressions uses panel data covering a five-year period from 2018 to 2022. The analysis examines member firms in the S&P 500 at the end of 2022 that were publicly traded in the previous five years. The empirical work excludes utilities and financial institutions, consistent with established finance research. The research frequently excludes both industries as they are highly regulated and, in the case of financial institutions, report different metrics of operations and performance. This produces a final sample of 290 companies.

From 2018 to 2022, there were 463 different CEOs in the 290 firm sample. Hand collecting the pictures from publicly available sources yields 455 readable photos that are then scored by de Kok’s fWHR calculator app (

de Kok, n.d.).

Appendix A lists all variables, their definitions, and how they were constructed.

The regression dependent variable is either the total ESG or one of the individual components: Environmental, Social, or Governance. I obtained ESG scores for these variables from S&P Global. As of spring 2024, S&P Global covers 13,500 firms worldwide, representing 99% of global market capitalization (

S&P Global, n.d.).

The S&P Global rates firms on a 0–100 scale, where 100 is the maximum score (

S&P Global, 2023). The score represents “a company’s performance on and management of material ESG risks, opportunities, and impacts informed by a combination of company disclosures, media and stakeholder analysis, modeling approaches, and in-depth company engagement via the S&P Global Corporate Sustainability Assessment (CSA)” (

S&P Global, 2023, p. 4). The score is a relative measure that compares the firm’s performance on ESG risks, opportunities, and impacts to other companies within the same industry.

A CSA includes one of 62 industry-specific surveys sent to the firm with approximately 120 total questions. If a question is unanswered, a team of experts will fill in the information if publicly available. If not available, the CSA assigns a zero.

The CSA covers each of the three dimensions, Environmental, Social, and Governance. In addition to climate strategy and environmental policy and management, the Environmental dimension includes energy, waste & pollutants, and water. Social topics span across issues such as community relations, human capital management, labor practices, and occupational health and safety. Finally, governance includes business ethics, corporate governance, product quality, risk and crisis management, and supply chain management. The S&P Global marks each of the three dimensions on a 0-to-100-point scale and then takes a weighted average of the three scores to obtain the total ESG score.

Each firm has a two-month participation window to gather and send the requested data. The first window begins in April, with the first score releases beginning in August. In all cases, the regression analysis uses ESG scores from as late in the calendar year as they appear, with none sooner than a September release. For most of the firms in the sample, the ESG measure is within three months of the end of their fiscal year.

To better understand both the content and outcome of a firm’s ESG rating, consider the current ESG rating for Tesla, Inc. The firm is in the automobile industry and has an ESG rating equal to 40. The record shows that there is a “medium” data availability, so some information must be collected by the S&P Global. Furthermore, Tesla is “Under Review”, which indicates that the S&P Global is completing a “Media and Stakeholder Analysis,” with the possibility that the ESG score may subsequently change.

The ESG score is broken down along the three different dimensions, E, S, and G, and also compares the outcomes to industry norms. Tesla is well below the maximum industry ratings in all three dimensions. In the case of its social ratings, Tesla scores a 29, which is below even the industry average. While the environmental score is greater than the industry average, it is still a middling mark, equal to 53.

Finally, other ESG ratings, such as the MSCI data, were considered for the analysis. However, measures of strengths minus concerns yield a scale that hovers near zero and may not be as intuitive as the 100-point index of the S&P Global. Moreover, like the MSCI data, the S&P’s ratings and those of its predecessor RobecoSAM go back two decades, and its protocol, followed in the Corporate Sustainability Assessment (CSA), has long been recognized as one of the most sophisticated ESG scoring methodologies.