Unmasking Short-Term Wealth Effects of M&A Deals in India: A Multi-Model Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Underpinnings and Literature Review

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Data Sources and Methodology

4. Results

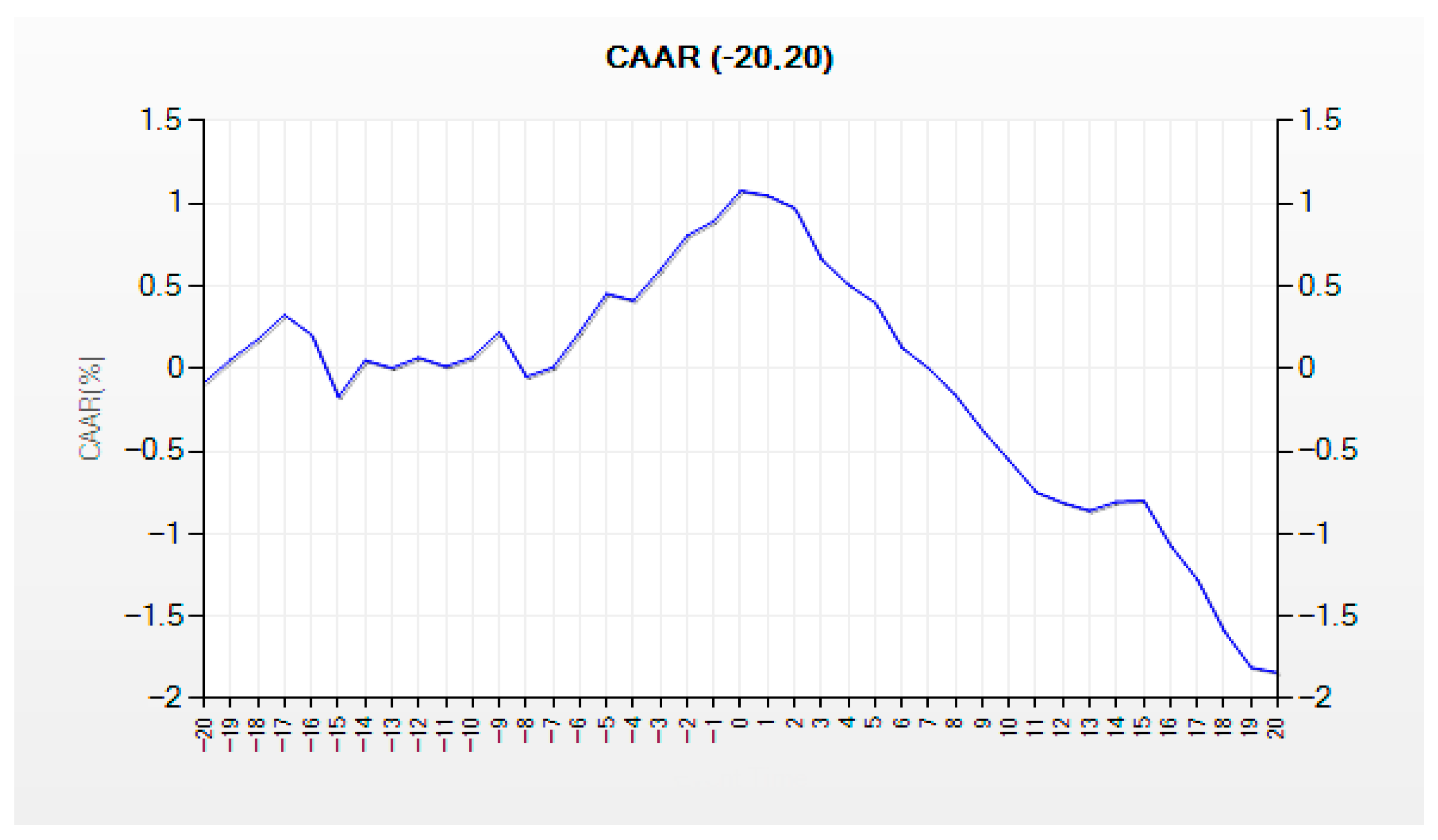

4.1. Pre-Announcement Period Results

4.2. Post-Announcement Period

4.3. Selected Other Window Periods

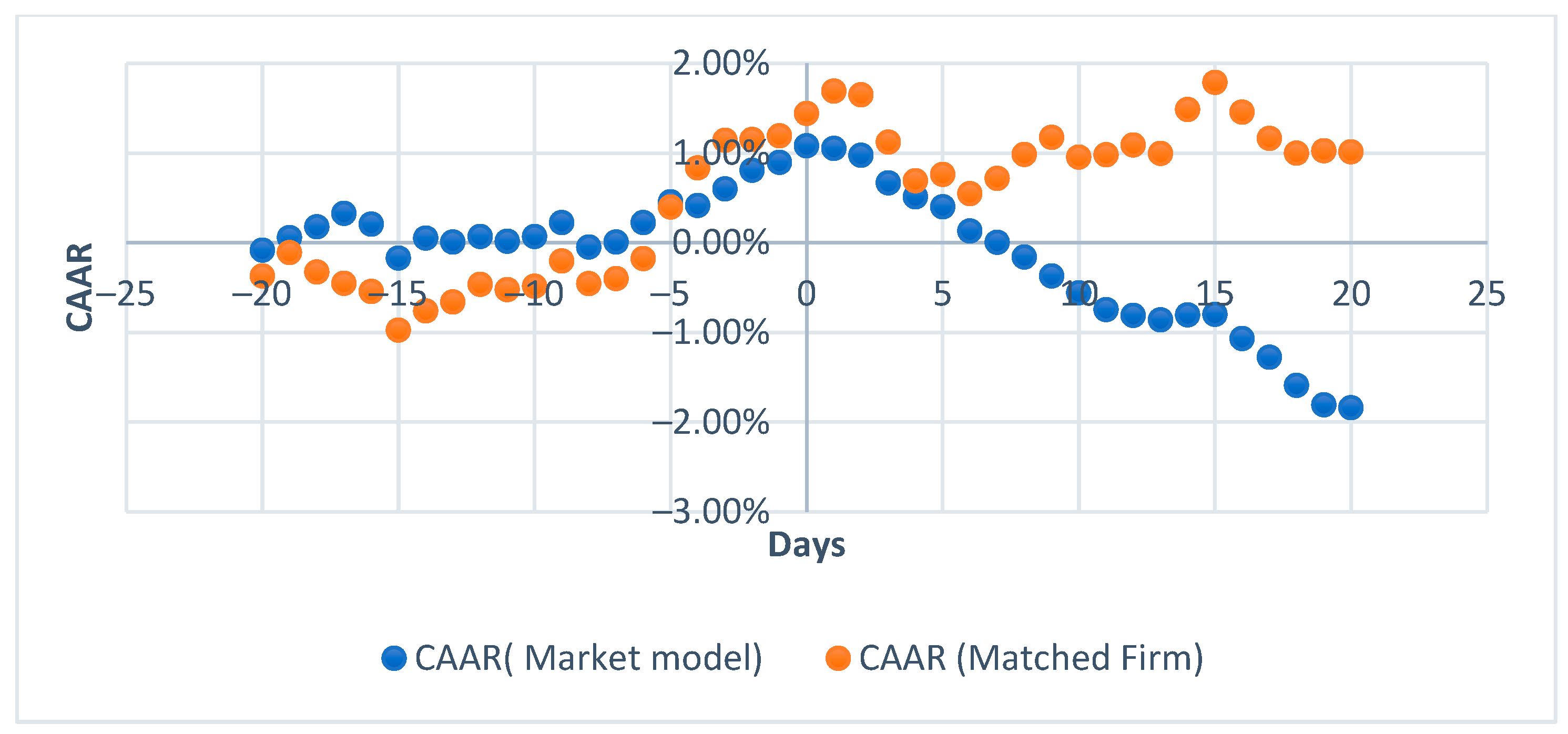

4.4. Matching-Firm Approach

4.5. Robustness Tests

5. Discussion

6. Managerial Implication

7. Limitations and Future Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, R., Chen, Y., Benjasak, C., Gregoriou, A., Nahar Falah Alrwashdeh, N., & Than, E. T. (2023). The performance of bidding companies in merger and acquisition deals: An empirical study of domestic acquisitions in Hong Kong and Mainland China. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 87, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S., Zhang, Y., & Lee, K. (2023). Short-term market reactions to domestic acquisitions in Hong Kong and Mainland China post-financial crisis. Asia-Pacific Journal Finance Studies 52, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Akben Selcuk, E., & Kiymaz, H. (2015). The impact of diversifying acquisitions on shareholder wealth: Evidence from Turkish acquirers. The International Journal of Business and Finance Research, 9(3), 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandridis, G., Petmezas, D., & Travlos, N. G. (2010). Gains from mergers and acquisitions around the world: New evidence. Financial Management, 39(4), 1671–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amewu, G., & Alagidede, P. (2018). Do mergers and acquisitions announcements create value for acquirer shareholders in Africa. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 23, 606–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, M., & Singh, J. (2008). Impact of merger announcements on shareholders’ wealth: Evidence from Indian private sector banks. Vikalpa, 33(1), 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybar, B., & Ficici, A. (2009). Cross-border acquisitions and firm value: An analysis of emerging-market multinationals. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 1317–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barai, P., & Mohanty, P. (2010, October 25). Short term performance of Indian acquirers–effects of mode of payment, industry relatedness and status of target. Industry Relatedness and Status of Target. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1697564 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Brown, S. J., & Warner, J. B. (1985). Using daily stock returns: The case of event studies. Journal of Financial Economics, 14(1), 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, I., & Kattuman, P. (2023). The impact of mergers and acquisitions on performance of firms: A pre- and post-TRIPS analysis of India’s pharmaceutical industry. Asia and the Global Economy, 3, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faff, R., Prasadh, S., & Shams, S. (2019). Merger and acquisition research in the Asia-Pacific region: A review of the evidence and future directions. Research in International Business and Finance, 50, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., Fisher, L., Jensen, M. C., & Roll, R. (1969). The adjustment of stock prices to new information. International Economic Review, 10(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, K., Netter, J., & Stegemoller, M. (2002). What do returns to acquiring firms tell us? Evidence from firms that make many acquisitions. The Journal of Finance, 57(4), 1763–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J. R., Lemmon, M. L., & Wolf, J. G. (2002). Does corporate diversification destroy value? The Journal of Finance, 57(2), 695–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, T. (2011). Determinants of short-term value creation for the bidder: Evidence from France. Journal of Management & Governance, 15, 157–186. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X., Yang, H., & Yang, P. (2024). The impact of cross-border mergers and acquisitions on corporate organisational resilience: Insights from dynamic capability theory. Sustainability, 16(6), 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S., Kashiramka, S., & Jain, P. K. (2020). Do frequent acquirers outperform in cross-border acquisitions? A study of Indian companies. Review of International Business and Strategy, 30, 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiymaz, H., & Baker, H. K. (2008). Short-term performance, industry effects, and motives: Evidence from large M&As. Quarterly Journal of Finance and Accounting, 47(2), 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kohers, N., & Kohers, T. (2000). The value creation potential of high-tech mergers. Financial Analysts Journal, 56(3), 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecky, K. J., Li, Z., Sugrue, T. F., & Tucker, A. L. (2018). Revisiting M&A with taxes: An alternative equilibrating process. International Journal of Financial Studies, 6(1), 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. (2009). Post-merger corporate performance: An Indian perspective. Management Research News, 32(2), 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinlay, A. C. (1997). Event studies in economics and finance. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1), 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, S. B., Schlingemann, F. P., & Stulz, R. M. (2004). Firm size and the gains from acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 73, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A., & Bakhshi, P. (2025). Shareholders’ wealth dynamics: Study of M&A announcements and target and acquirer financial performance in the Indian corporate landscape. Managerial Finance, 51(10), 1684–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, N., Yadav, S. S., & Jain, P. K. (2014). Impact of domestic and cross-border acquisitions on acquirer shareholders’ wealth: Empirical evidence from Indian corporate. International Journal of Business and Management, 9(3), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, N., Yadav, S. S., & Jain, P. K. (2015). Market response to internationalization strategies: Evidence from Indian cross-border acquisitions. IIMB Management Review, 27(2), 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, P., Shauki, E. R., Darminto, D., & Prijadi, R. (2020). Motives, governance, and long-term performance of mergers and acquisitions in Asia. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1791445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, M., & Williams, J. (1977). Estimating betas from nonsynchronous data. Journal of Financial Economics, I(3), 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, S., Banerjee, S., & Deisting. (2012). The impact of M&A announcement and financing strategy on stock returns. Evidence from BRICKS markets. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(11), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. S. (2018). Profitability of mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from India’s high-tech industries. The Indian Economic Journal, 66, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsanam, S., & Mahate, A. A. (2003). Glamour acquirers, method of payment and post-acquisition performance: The UK evidence. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 30(1–2), 299–342. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H., Fang, S., & Jiang, D. (2022a). The market value effect of digital mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from China. Economic Modelling, 116, 106006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H., Zhang, C., & Xu, Y. (2022b). The impact of digital mergers and acquisitions on market value in China. Journal Business Research, 139, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Teti, E., & Tului, M. (2020a). Mergers and acquisitions in the infrastructure market: An analysis of the utilities sector. Utilities Policy, 64, 101043. [Google Scholar]

- Teti, E., & Tului, S. (2020b). Do mergers and acquisitions create shareholder value in the infrastructure and utility sectors? Analysis of market perceptions. Utilities Policy, 64, 101053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M. M. (2000). Corporate takeovers, strategic objectives, and acquiring-firm shareholder wealth. Financial Management, 29, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Y., Segara, R., & Feng, J. (2019). Stock price movements and trading behaviors around merger and acquisition announcements: Evidence from the Korean stock market. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 15(4), 593–610. [Google Scholar]

- Yuce, A., & Ng, A. (2005). Effects of private and public Canadian mergers. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 22(2), 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zaremba, A., & Płotnicki, M. (2016). Mergers and acquisitions: Evidence on post-announcement performance from CEE stock markets. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 17(2), 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, Q., Yu, X., & Ma, Q. (2023). Equity overvaluation, insider trading activity, and M&A premium: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 80, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L., Shen, J., & Yeerken, A. (2024). Impact analysis of mergers and acquisitions on the performance of China’s new energy industries. Energy Economics, 129, 107189. [Google Scholar]

| Industry-Wise Distribution of Firms | Number of Firms | Number of Firms (In %) |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Sector | ||

| 30 | 6.68 |

| 27 | 6.01 |

| 91 | 20.27 |

| 21 | 4.68 |

| 27 | 6.01 |

| 37 | 8.24 |

| 36 | 8.02 |

| 25 | 5.57 |

| 9 | 2.00 |

| 17 | 3.78 |

| Service Sector | ||

| 11 | 2.45 |

| 24 | 5.35 |

| 5 | 1.11 |

| 7 | 1.56 |

| 44 | 9.80 |

| 27 | 6.01 |

| 11 | 2.45 |

| Total | 449 | 100 |

| Window Period | CAAR (%) | Time-Series t-Test | Cross-Sectional t-Test | Patell Z | Boehmer Z | Corrado Rank | Sign Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [−1, 0] | 0.27% | 1.209 | 1.067 | −2.742 * | −0.710 | 1.884 * | 1.385 |

| [−2, 0] | 0.48% | 1.741 ** | 1.448 | −2.786 * | −0.672 | 1.827 * | 0.912 |

| [−5, 0] | 0.86% | 2.195 * | 1.972 * | −1.254 * | −0.489 | 2.331 ** | 2.613 * |

| [−10, 0] | 1.06% | 2.018 * | 1.767 ** | −0.995 *** | −0.689 | 2.158 * | 1.479 |

| [−15, 0] | 0.87% | 1.371 | 1.199 | −6.696 *** | −0.784 | 2.277 ** | 3.086 ** |

| [−20, 0] | 1.08% | 1.480 | 1.288 | −6.821 *** | −0.793 | 2.047 ** | 3.181 ** |

| [0, 0] | 0.19% | 1.205 | 1.042 | −2.146 * | −0.650 | 1.742 * | 1.194 |

| Window Period | CAAR (%) | Time-Series t | Cross-Sectional t | Patell z | Boehmer z | Corrado Rank | Sign Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0, 0] | 0.190 | 1.205 | 1.043 | −2.146 * | −0.650 | 1.742 * | 1.194 |

| [0, 1] | 0.150 | 0.680 | 0.569 | −4.831 *** | −0.856 | 1.853 * | 0.438 |

| [0, 2] | 0.070 | 0.240 | 0.195 | −6.650 *** | −1.005 | 0.900 | 0.154 |

| [0, 5] | −0.470 | −1.197 | −0.978 | −9.143 *** | −1.154 | −1.094 | −0.979 |

| [0, 10] | −1.460 | −2.770 * | −2.282 * | −16.835 *** | −1.180 | −2.165 ** | −2.208 ** |

| [0, 15] | −1.700 | −2.679 * | −2.247 ** | −10.747 *** | −1.231 | −1.820 * | −1.168 |

| [0, 20] | −2.750 | −0.871 * | −1.152 ** | −16.832 *** | −1.243 | −2.594 * | −2.398 ** |

| Event Window | CAAR (%) | Time-Series t | Cross-Sectional t | Patell z | Boehmer z | Corrado Rank | Sign Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0, 0] | 0.190 | 1.206 | 1.043 | −2.146 ** | −0.650 | 1.742 * | 1.194 |

| [−1, 1] | 0.220 | 0.816 | 0.700 | −5.008 *** | −0.856 | 1.924 * | 0.438 |

| [−2, 2] | 0.340 | 0.957 | 0.775 | −6.416 *** | −0.921 | 1.211 | 1.478 |

| [−5, 5] | 0.220 | 0.414 | 0.357 | −6.987 *** | −0.956 | 0.362 | −0.035 |

| [−10, 10] | −0.580 | −0.795 | −0.643 | −12.180 *** | −1.016 | −0.424 | 0.533 |

| [−15, 15] | −1.020 | −1.149 | −0.920 | −12.150 *** | −1.011 | −0.017 | 0.060 |

| [−20, 20] | −1.880 | −1.849 * | −1.423 | −14.320 *** | −1.045 | −0.737 | 0.154 |

| Event Phase | Window | CAAR (%) | Time-Series t | Cross-Sectional t | Patell z | Boehmer z | Corrado Rank | Sign Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Anticipation 1 | [−20, −5] | 0.420 | 0.656 | 0.570 | −5.969 *** | −0.835 | 1.186 | 1.194 |

| Market Anticipation 2 | [−5, −1] | 0.690 | 1.927 * | 1.788 * | −0.348 | −0.359 | 1.737 * | 2.045 ** |

| Event Day Reaction | [0, 0] | 0.190 | 1.206 | 1.043 | −2.147 ** | −0.650 | 1.742 * | 1.194 |

| Centered Reaction | [−15, 10] | −0.770 | −0.956 | −0.756 | −13.675 *** | −0.996 | 0.002 | 0.438 |

| Post-Announcement 1 | [2, 10] | −1.610 | −3.384 ** | −2.939 ** | −12.740 *** | −1.275 | −3.268 ** | −2.870 ** |

| Post-Announcement 2 | [5, 20] | −2.380 | −0.846 *** | −3.394 ** | −10.621 *** | −1.309 | −2.441 ** | −1.925 ** |

| Total Abnormal Return | [−20, 20] | −1.880 | −1.850 * | −1.423 | −14.323 *** | −1.046 | −0.737 | 0.154 |

| Event Phase | Window | CAAR (%) | t-Test Cross-Sectional | Corrado Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Anticipation | [−20, −5] | 0.40 | 0.457 | 0.059 |

| Market Anticipation | [−5, −1] | 1.37 | 2.501 ** | 3.024 *** |

| Event Day Market Reaction | [0, 0] | 0.25 | 0.984 | 1.103 |

| Market Reaction Centered on the Day | [−15, 10] | 1.48 | 1.319 | 0.839 |

| Post-Announcement Market Return | [2, 10] | −0.74 | −1.017 | −1.396 |

| Post-Announcement Market Return | [5, 20] | 0.32 | 0.361 | −0.158 |

| Total Abnormal Return | [−20, 20] | 1.01 | 0.702 | 0.008 |

| Event Window | Constant Mean Return Brown and Warner (1985) | Market Adjusted Return MacKinlay (1997) | Market Model (OLS) | Market Model (Scholes/Williams) | CAPM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAAR | t-Statistics | CAAR | t-Statistics | CAAR | t-Statistics | CAAR | t-Statistics | CAAR | t-Statistics | |

| [−20, −5] | −0.170 | −0.205 | 1.220 | 1.855 ** | 0.420 | 0.570 | 0.720 | 0.939 | −5.830 | −5.524 * |

| [−5, −1] | 0.620 | 1.475 | 0.950 | 2.584 * | 0.690 | 1.788 ** | 0.460 | 1.107 | −1.270 | −2.708 * |

| [0, 0] | 0.130 | 0.635 | 0.330 | 1.783 ** | 0.190 | 1.043 | 0.200 | 1.076 | −0.200 | −1.065 |

| [−10, 10] | −0.970 | −0.960 | 0.790 | 1.072 | −0.580 | −0.644 | −1.010 | −1.098 | −8.790 | −6.731 * |

| [2, 10] | −1.730 | −2.899 * | −0.990 | −2.033 * | −1.610 | −2.939 * | −1.670 | −3.034 | −5.140 | −7.809 * |

| [5, 20] | −2.760 | −3.526 * | −1.230 | −2.112 * | −2.380 | −3.394 * | −2.400 | −3.454 | −8.600 | −8.730 * |

| [−20, 20] | −2.830 | −1.905 * | 0.670 | 0.671 | −1.880 | −1.423 | −1.950 | −1.551 | −17.880 | −7.711 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Satapathy, D.P.; Soni, T.K.; Mishra, A.K. Unmasking Short-Term Wealth Effects of M&A Deals in India: A Multi-Model Analysis. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120718

Satapathy DP, Soni TK, Mishra AK. Unmasking Short-Term Wealth Effects of M&A Deals in India: A Multi-Model Analysis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):718. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120718

Chicago/Turabian StyleSatapathy, Debi Prasad, Tarun Kumar Soni, and Ashok Kumar Mishra. 2025. "Unmasking Short-Term Wealth Effects of M&A Deals in India: A Multi-Model Analysis" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120718

APA StyleSatapathy, D. P., Soni, T. K., & Mishra, A. K. (2025). Unmasking Short-Term Wealth Effects of M&A Deals in India: A Multi-Model Analysis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120718