Abstract

In recent years, sport governing bodies (SGB) have been the subject of serious questions regarding their governance structures and decision-making processes. SGB that fail to implement regulatory mechanisms and to improve their governance structures and processes risk being confronted with severe ethically sensitive issues outside and inside the fields, which may eventually result in negative publicity and reduced demand (e.g., fans, sponsors) or financial support (e.g., from governments). This study examines selected regulations and practices of North American professional sports leagues in light of good governance principles. By adopting a qualitative research design, we investigate if there is a need for reforms to be employed by the leagues to comply with core dimensions of governance and thus reduce the risk of not being prepared to deal with ethically sensitive issues that may come up. Our critical analysis suggests that essential reforms need to be employed by the leagues to comply with core principles of good governance. In terms of democracy, professional leagues need to recognise stakeholder interests, implement innovative participation mechanisms, and apply diversity and inclusion policies for board composition. On transparency, it is required to publish internal regulations and financial information despite lax regulations on disclosure policies in the United States. Concerning accountability, professional leagues should separate their disciplinary and executive branches to avoid the concentration of power and potential conflict of interest in the relationship between the commissioner and team owners.

Keywords:

good governance principles; democracy; transparency; accountability; ethics; risk; US sport 1. Introduction

In recent years, sport governing bodies (SGB) have come under serious questioning regarding their governance structures and decision-making processes. By governance failures, Henry and Lee (2004) mean a lack of coordination among relevant bodies, deficiencies in regulating potentially harmful practices, and a flaw in establishing fair, transparent, and efficient procedures. Sports organisations both on national and international levels face a myriad of risks related to ethically sensitive issues and several organisations have received criticism in the past for their handling of different matters. Professional sports leagues in North America are no exception to this, as their approaches to dealing with ethically sensitive issues such as doping, cheating, concussions, domestic violence, racial discrimination, and homophobia, to name a few, have been criticized by broad sectors inside and outside sports (Shropshire 2004; Gregory 2004; Wolf 2010; Rapp 2012; Augelli and Kuennen 2018; Conklin 2020).

The high level of autonomy of sports organisations, an extremely rule-oriented context, and the increasing commercialisation of sport (e.g., Geeraert 2013; Hillman 2016) have called into question the legitimacy of sports organisations and have led to the development of criteria and indicators of good practice and ethical conduct in the governance of sports organisations. The Sport Governance Observer developed by Play the Game in 2013, for example, resulted in clear criteria for desirable behaviour in sport organisations (Alm 2013). Thompson et al. (2022) explain that, as seen by many, improving organisational governance by implementing policies is regarded as central to the performance and effective governance practices of sport organisations.

Professional sports leagues in North America have emerged as entities in which profit maximisation and shareholder supremacy have been the fundamental principles of decision-making. The lack of clarity about the legal nature of North American professional leagues, their self-governance mechanisms and the weight of economic performance as a determining factor in their governance raise a number of ethical concerns that deserve to be studied. While it is true that the business operations of North American professional sports leagues have been a fertile research topic for scholars in the field of economics and management (e.g., Zimbalist 2002; Szymanski 2003; Blair 2011; Leeds et al. 2018), studies on the ethical issues and conflicts of interest arising from this business model in sport are limited (e.g., Willisch 1993; Lentze 1995; McLin 2016). It is precisely this gap that we have found through our research, which highlights the need to examine North American professional sports leagues through the lens of ethical standards and principles of good governance.

In this paper we examine selected regulations and practices of professional sports leagues in North America in light of good governance principles. By adopting a qualitative research design analysing a plethora of secondary sources, we look into issues related to the governance principles democracy, transparency and accountability. In a recent review, Thompson et al. (2022) identified these three principles to be the most frequently discussed criteria in academic discourse (and in the grey literature). Also, Geeraert et al. (2014) state that these three principles constitute central dimensions of good governance. This paper aims to investigate whether leagues must undertake reforms to comply with these core dimensions of governance and thus reduce the risk of being unprepared to deal with ethically sensitive issues that may arise.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: First, we lay out our theoretical framework on the principles of (good) governance in sport. Then, we present the context of our analysis and describe core features of North American professional sports leagues. The research methods are described next, followed by the results and their discussion. The paper ends with a general conclusion and some practical implications as well as limitations of the study that may invoke further research.

2. Theoretical Framework: Principles of (Good) Governance

Since the late twentieth century, the term ‘governance’ has played a central part in contemporary social science debates (Bruyninckx 2012). The concept of governance is commonly used in the spheres of policymaking, regulation, standards, and the exercise of authority. The Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance (1992), known in the U.K. as the Cadbury Committee, defined it as ‘the system by which organisations are directed and controlled’. Shleifer and Vishny (1997) maintain that corporate governance is how investors are assured of a return. Several authors have criticized these approaches for their limited scope and descriptive approach (McNamee and Fleming 2007). McNamee and Fleming’s main concern is that such definitions exclude normative ideals. They claim that it is not only a matter of describing the type of governance but also of thinking of corporate governance as a concept that entails both descriptive and evaluative standards.

Good governance is a term that became popular in the 1990s when the World Bank introduced it as an unavoidable condition for countries requiring financial aid. Providing additional funding was subject to countries following these international financial organisations’ ‘good governance’ recommendations. The OECD (2015) stated that good governance seeks an atmosphere of trust, transparency, and accountability necessary for fostering long-term investment, financial stability, and business integrity, thereby supporting more robust growth and more inclusive societies. It is clear that these concepts are oriented towards a set of principles and therefore correspond to the normative dimension, which help address what is expected from organisations. Although Geeraert (2018) recognises recent efforts in sports, he concludes that there is still a certain inertia hampering the establishment of better governance in sports organisations. Geeraert credited this inaction to the lack of generally clear frameworks and the unavailability of benchmarking tools for good governance. Chappelet and Mrkonjic (2013) claim that the absence of universal principles in sports is motivated by the fact that sports organisations are rarely identical. Risk analysis needs to be employed by each organisation individually to identify which risks it is exposed to and to assess incidents or actions that may have a negative impact on the organisation (Transparency International 2021). Therefore, the relevance of governance indicators may vary across organisations. Nevertheless, as outlined above, certain principles (namely democracy, transparency and accountability) appear to be more frequently discussed than others (e.g., responsibility, solidarity and integrity) in the debate (Thompson et al. 2022). In the following subsections, the three most frequently used terms that also form the basis of this study are discussed in turn.

2.1. Democracy

Democracy is one of the most protected values of western societies, commonly referred to as the ‘government by the people’, where the power resides in the people and decisions are made by individuals directly or by elected representatives (Mittag and Putzmann 2013). This traditional concept of democracy is hardly strictly applicable to the North American sporting model, which even shows less democratic features as compared to, for example, the European model. Yet it might offer some essential ethical standards to pursue. Democracy is usually associated with governments and the public sphere, while it does not have the same acceptance among private entities. However, scholars have built a case for extending democratic principles into corporate settings (De Jong and Van Witteloostuijn 2004). According to Garrett (1956), democracy has a ringing appeal to Americans because of its political implications, but in a corporate sense, its meaning is restricted. Dahl (2020) maintains that a democratic system consists of designing regulations and principles that determine how the association members should conduct the decision-making process. More concretely, Geeraert (2022) summarises that democracy contains a set of rules that establish (electoral) competition, and collective participation (by affected groups) in decision-making and deliberation (fair and open debates).

2.2. Transparency

Forssbaeck and Oxelheim (2014) defined transparency as the entire disclosure of relevant information in a timely and systematic way, made available for observation and decision-making by stakeholders. They also acknowledge transparency as a connection with openness, clarity, access to information, and communication. Hood (2010) advocates that transparency helps bring corruption situations to the proper authorities’ attention and leads to an open culture that benefits stakeholders. Roberts (2006) attributes the failure of organisations in part to the culture of secrecy and advocates for a culture of transparency. Similarly, Geeraert (2022) refers to McCubbins and Schwartz (1984) and points out that the major benefit of transparency is the decrease in information asymmetries between an organisation and its stakeholders; the availability of information indeed allows stakeholders (and others) to detect (the potential of) wrongdoings.

2.3. Accountability

While transparency refers to business conduct in a manner that makes decisions, regulations, and policies visible from the outside, (internal) accountability denotes the obligation of an individual or organisation to respond internally to how they have conducted their affairs (Hood 2010). According to Bovens (2007), accountability implies a social relationship between an actor and a forum. The actor is obligated to explain and defend a behaviour, and the forum may question such conduct. As a result of this relationship, the actor might face some sanctions in case of negative judgement. Bovens makes particular reference to the impact of accountability in preventing excessive concentration of power in organisations. According to Geeraert (2022) accountability consists of (a) a clear separation of powers (executive, judicial, and supervisory) and (b) an internal system to monitor decision-makers’ compliance with rules. These two components together help deter undesired behaviour by increasing the likelihood of negative consequences (ebd.). The idea of a separation of powers, consequently, it is an excellent basis upon which to analyse the possible concentration of disciplinary, political, and executive power and potential conflicts of interest that are not being well-addressed in North American professional sports leagues.

3. Logic and Structure of North American Professional Sports Leagues

Professional sports leagues in North America emerged as entities in the spirit of the greatest boom of capitalism and an expansion of corporate culture in the first half of the 20th century (Kristol 1975), with profit maximisation and shareholdership being the overriding principles (Fort 2000; Andreff and Staudohar 2002). American professional leagues are considered exemplary organisations, usually supported by arguments like successful fan engagement, a high economic return, good sporting performance, and organisation longevity. Jozsa (2010) argues that despite issues such as player strikes, integrity concerns, and external problems such as economic recessions and armed conflicts, clubs within these professional leagues have remained operational as profitable businesses and an essential element of American culture and history.

The business operations of North American professional sports leagues have been a fertile research subject for scholars in the field of economics and management for more than thirty years due to their unique governance structures and sound financial performance (Jozsa 2010). However, scholarship about ethical problems and conflicts of interest that arise from this corporate system in sport is limited. Therefore, it is pertinent to question whether the governance of these professional leagues has been examined through the lens of ethical standards and principles of good governance.

One of the main obstacles when analysing the organisational structure of North American professional sports leagues is the lack of clarity regarding the entity’s classification (league corporations, partnerships, or associations). One of the significant consensuses is that their organisational structures are problematic, to say the least (Davis 2018). Grossman (2014) finds a problem in the fact that although the components of the structural organisation are known, its legal classification as an entity is not. Organisational forms define the rights and duties of the member team owners, management and stakeholders.

According to Conrad (2009), professional leagues were created as a self-governance mechanism for a group of competitive teams, which have an organisational structure for decision-making focused on players and owner discipline, financial management, and expansion and relocation of league clubs. These last two elements have been intimately related to the league management’s economic dimension and, therefore, have had the most weight in determining their governance structures. In this respect, Lentze (1995) concludes that sources of revenue and cost have played an essential part in defining the organisational structure of professional leagues.

The MLB, the NHL, the NFL, and the NBA are established as unincorporated associations that consist of their respective member clubs. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) from the US, an unincorporated association is “an association of two or more persons formed for some religious, educational, charitable, social or other non-commercial purposes”. The four leagues clearly state in their founding documents that they are non-profit organisations. For most scholars of law, an unincorporated association is not a legal entity and therefore does not have limited liability, but its members do. Members may vary from time to time, and they agree on their organisation and common purposes by utilising a written constitution. Committees chosen by the members usually manage their matters. This legal approach helps understand the decision-making process of professional league members since the member clubs share revenues. Notwithstanding, each franchise belongs to separate owners or corporations with distinct incomes, assets, and market values from those of other member clubs (Flynn and Gilbert 2001).

Unlike other national sports organisations, such as national Olympic committees (NOCs) and national sports federations, the unincorporated condition of professional sports leagues makes the need to be accountable towards society less obvious. For example, while it is correct to assert that incorporated non-profit organisations such as the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) are not agencies of the United States (US) government, there are instances where the line between the private and government sectors is, at best, blurry (Congressional Research Service 2011). It is possible to argue that, at least in some cases, the private character of these corporations is reasonably in question. The fact that USOPC’s recognition as the governing body of sports in the US comes from Congress is a testament to the public’s interest in these organisations. This is not the case for professional leagues and makes a difference when analysing their structure and governance.

Longley (2013) highlights the closed nature of North American sports league governance, since their club members keep strict control over all facets of the game, without any external organisation regulating the game. Technically, leagues are private enterprises and the relationship between franchise members is contractual and not of public interest (Grossman 2014). In short, they are self-governed private entities protected by exceptions to antitrust laws. New members are only acknowledged with the approval of other team owners, and franchisees are protected from competition with territorial rights over attractive cities. The author expands by arguing that the lack of competition allows leagues to explicitly select an arbitrary structure and implement policies that maximise revenues. Thus, North American professional sports leagues differ in many aspects from sports leagues in other parts of the world. Van Bottenburg (2011) lists different reasons why professional sports leagues in the US developed differently to, for example, European ones that are largely driven by an association mindset. According to the author, leagues in the US developed in relative geographic and cultural isolation from processes of organisation, regulation, and standardisation in Europe, what led to ‘far more room for all kinds of commercial initiatives to establish closed professional leagues under profit-oriented managerial control’. As a consequence, as discussed below, North American professional sports leagues also have a different approach to dealing with stakeholder interests and representation.

Apart from the fact that North American professional leagues are a monopoly in practice, it is appropriate to analyse the owners’ interests. Leagues are composed of a group of individual owners but collectively also own the league as a whole. It means that they play a double role: they pursue the maximisation of profits for individual teams and manage the entire league in the owners’ best interest. According to Longley (2013), the latter role implies making the most crucial decisions for the league’s success. They include potential expansions, relocations, salary policies, and revenue sharing. In McLin’s (2016) view, this double role results in what he calls a ‘collective action problem’: self-interested owners would focus on actions that benefit their own club rather than the league and other stakeholders at large. As a consequence, due to the requirement of a supermajority vote of the owners, this may prevent the implementation of more efficient policies by the commissioners. Furthermore, this constellation may also easily impede innovation and the adoption of reforms to address issues such as a lack of transparency or accountability, if these are not congruent with the (economic) interest of all individual owners.

With greater or lesser similarities in their regulations, some authors support the idea that the four professional leagues share most of the principles. For example, McLin (2016) stresses that each of the four major professional sports leagues have an extraordinarily similar governance structure reflected in their respective constitutions. In general, they show a peculiar mix of corporate principles and particularities that address the nature of sporting organisations. The above-described landscape is the basis for arguing that professional leagues take the best of each model to guarantee profits while avoiding regulations from the business sector and societal demands to sport organisations. Therefore, it leads to severe problems of ethics and integrity concerning society and internal functioning.

4. Research Methods

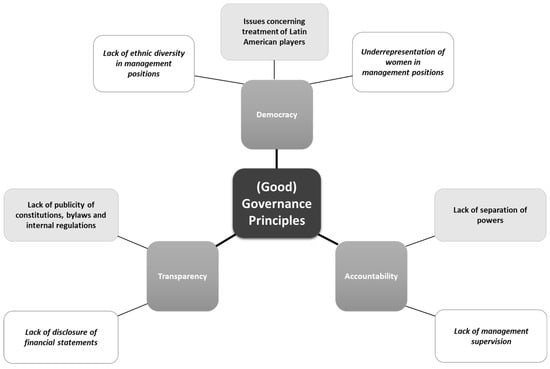

This qualitative research focuses on the social sphere, whose methodological orientation is documentary in nature. This type of research responds to a systematic search, analysis, and synthesis of information from secondary sources. It refers to an exhaustive examination of documents that contain relevant and systematic information on the phenomenon explored (Bailey 1994). The procedure involved three fundamental steps: (1) Extensive document search: a keyword-based search with words such as ‘governance’, ‘sports governance’, ‘corporate governance’, and ‘principles of governance’ paired with keywords related to North American professional sports leagues resulted in a plethora of data that entered the analysis, thus ensuring data triangulation. A multitude of word combinations allowed us to assess previous research in this area and identify gaps in the literature. Furthermore, through desk research, we identified discursive heights of attention (e.g., scandals, important events or decisions) that also served as key terms (Hajer 1997). This collection of data was dynamic in the sense that new keywords could arise as a result of our directed search until theoretic saturation was attained (Strauss and Corbin 1990). (2) Organisation of the data: we organised and grouped the data in a deductive way based on the three (good) governance principles under consideration. (3) Critical analysis and synthesis of the data: the exhaustive reading technique involved identifying primary and secondary themes related to the three principles, which allowed the understanding and interpretation of the ideas expressed in the text. It involved going deeper by consulting various authors and sources and making evident the remaining ideas that were overlapping. Investigator triangulation in the form of intersubjective verifiability was addressed through regular meetings between research team members during which agreement on the interpretation of the data was reached (Guest et al. 2012). Finally, we synthesised the data to construct a coherent pattern. Figure 1 shows the final coding tree with our three main principles under consideration as well as the different main themes that were identified in the data. The themes written in italics were not included in the analysis for research economic reasons (see information in the limitations section at the end of the paper).

Figure 1.

Final coding tree showing the three principles and themes that emerged from the data.

We acknowledge that the chosen methodological procedure impacts the results and findings of the research. Piggin et al. (2009, p. 91) point out that, in line with Foucauldian theorization, it is acknowledged that controlling and examining all ‘data’ on a given subject is not possible. As a consequence, an important assumption underlying our study is that the entire amount of information on the topic could never be covered. Rather, the chosen documents and examples represent focal points in a debate. It is also worth noting that the research process was partially constrained by the lack of relevant information on the leagues’ internal regulations. The lack of publicity of constitutions and bylaws on the official websites of North American professional sports leagues, beyond being a constraint, reveals the problem of transparency suffered by the governance of these organisations. This governance flaw will be discussed in Section 5.2 in particular.

5. Results and Discussion

In the following sections, we present to what extent the described structures and regulations are compatible with the good governance principles of democracy, transparency, and accountability. We illustrate deficiencies in each dimension drawn from different examples. Regarding democracy, we look into the mechanisms employed by the leagues towards stakeholder representation and participation. Regarding transparency, the availability of information with a concrete focus on the publicity of constitutions, bylaws, and internal regulations is critically investigated. Finally, regarding accountability, we assess the role of the leagues’ commissioners and their powerful position within the structures.

5.1. Democracy: Representation and Participation Mechanisms

Despite an evolution of corporate responsibility (Crane et al. 2019) and considering some stakeholder rights in North America, the current corporate model is still determined mainly by decisions exclusively made by shareholders and management. Jackson (2011) asserts that most groups and individuals impacted by the conduct of American companies have no voice in their governance structures. Sports organisations have been no strangers to these concerns about athletes and stakeholders’ lack of influence in decision-making bodies. Geeraert et al. (2014) claim that sports organisations’ stakeholders have been excluded from policy processes pivotal to the regulations that govern their activities.

This phenomenon is clearly observable in North American professional sports leagues. The original wording in their constitutions state that they represent an agreement between their constituent parties (team owners). Therefore, they are governed by the rules of contract law (Davis 2018). In the framework of liberal democracy, in which contractual relations are protected from the intervention of third parties, the involvement of agents outside the traditional governance of these leagues, such as employees and fans, is infrequent, not to say non-existent.

After an exhaustive review of constitutions, bylaws and internal regulations of professional sports leagues in North America, there were no indications of any formal representation of stakeholders in their governance structures other than the team owners. Even less observed were any mechanisms of active participation by players, coaches, referees, or spectators in governance choices. Based on the analysis of all these powers being attributed to the commissioner and the board, it can be concluded that the constitutions of these leagues correspond to a governance system typical of shareholder supremacy.

The shareholder approach is traditionally understood as one that mainly considers profit maximisation favouring stockholders. It defines the primary duty of a company’s management bodies as the maximisation of shareholder capital (Friedman 1962). Velasco (2010) argues that because shareholders are ‘owners’ of the company, it must be governed in the owners’ best interest, which precludes the participation of other organisation members in the decision-making process. These principles of the American business culture have been observed in some way in professional sports leagues. Most of their governance decisions are made based on profit-maximisation approaches, and owners and commissioners dictate governance entirely.

The shareholder approach has been an object of broad criticism for its promotion of unethical conduct since it applies the rights claim of shareholders to excuse failure to consider the rights of other groups. In addition, the growing and sustained power of corporations has opened the discussion about the decision-making process within these private entities. Sports leagues have been no exception due to of the particular interest of a large portion of society, public investment to build sports facilities, and the effects that governance may have on critical agents such as athletes, coaches, referees, spectators, and society as a whole. These concerns about the decision-making process mainly raise challenges in the participation of those affected stakeholders and the absence of democratic practices.

To further illustrate our argument, we provide a selected example from baseball to illustrate a lack of mechanisms for stakeholder representation and participation, such as is the case of Latin-American players in MLB. Disadvantaged youths and families from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, or Mexico, for instance, often see North American baseball as a way to escape poverty. Since the US government has no international jurisdiction, MLB scouts operate with almost complete freedom to recruit Latin American players at a very young age, even before they finish high school (Marcano and Fidler 1999). Because Latin American baseball players are not covered by the regulated draft system of North American athletes, the scouting system takes advantage of the rampant poverty that reigns in these countries. As an MLB team representative, a scout with the power to sign baseball prospects has huge leverage over vulnerable families from poverty-stricken countries (Regalado 1998). Marcano and Fidler (1999) add that these facts lead Latino prospects to be typically eager to accept any conditions an MLB scout puts in front of them while receiving any of the signing incentives that US baseball prospects receive. Fierce competition among scouts in an unregulated environment has also led to the signing of younger and younger prospects, without offering any incentive to complete their formal education. It undoubtedly represents a significant impact on the educational development of these young people and is a determining factor in the functioning of the local leagues in these countries. It denotes that the promise of millionaire contracts in North America has encouraged corrupt methods by scouts seeking to take advantage of the region’s juvenile talent. Rosentraub (2000) affirms that ethical implications raised by MLB’s foreign activities validate that several constituencies are affected and proposes that a shared model of decision-making might be more suitable for representing different stakeholder interests.

The mentioned example clearly demonstrates that under the current scenario, the leagues risk not adequately taking into account the interests of stakeholders that are crucial to the leagues’ continuing success. To avoid this, a risk management-based recommendation would be to implement changes in the representation and participation of these stakeholders. The intellectual reference point of most demands for further democratic practices in corporations is stakeholder theory, which contradicts shareholder theory. According to Blount (2015), the rationale for stakeholder theory lies in the fact that organisations have several constituent entities, which have an influence on or are influenced by the practices and decisions that take place within the business. Therefore, their interest must be considered for the successful governance of these organisations through specific mechanisms of representation and participation.

Beyond recognising these interests, the real problem at hand is whether stakeholders would have a place at the decision-making table and, in particular, if their interests should be treated equally or similarly to those of shareholders. Greenfield (1997) defends the equal right of stakeholders, arguing that shareholders invest their economic resources with confidence that managers can use the company’s productive capabilities to secure and increase profitable returns. Similarly, workers attend work because they believe that managers can organise their job skills in such a way as to make them more productive and guarantee them appropriate compensation. Like stockholders, employees depend on the care, performance, and ethics of managers. This approach, applied to professional leagues, would equalise the interests of crucial stakeholders such as players, coaches, and referees with those of team owners. The former consider that their physical and intellectual skills are productive only within the framework of the league, and their interests must be protected by management bodies, in the same way as the owners, who invest their money for profit-making. Equal rights when participating in governance decision-making would imply for professional leagues that crucial stakeholders also sit on boards, as the current representation methods do not meet the current needs of these stakeholders.

It is undeniable that the bargaining power of players has increased in parallel with the strengthening of players’ associations, which in practice operate as labour unions. However, they are not considered part of the leagues’ governance structure, as is the case with the vast majority of companies in North America. On this matter, Davis (2018) has called to differentiate interests as employees from interests as stakeholders, appealing to the representation failures seen in the NBA and the role of the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA). In response to the Anglo-American shareholder primacy norm, proposals for alternative mechanisms of participation and representation have already been made in corporate governance and to a lesser extent in the governance of sports organisations. For instance, Jackson et al. (2004) refer to the case of the German codetermination model, in which employee participation is institutionalised at the level of boards and work councils. It means giving one or more employee representatives a formal position at the boardroom table to constitute a balance of power vis-à-vis the shareholders regarding appointing managers. Under this scheme, if applied to the professional leagues, one or more representatives of the stakeholders, whether players, coaches or referees, may have a say in the selection of the commissioner, or perhaps the power to appoint committees for a specific purpose, provided that their interests are affected.

The most evident obstacle to achieving such participation is that none of the constitutions and bylaws of the four professional leagues contemplates this; in fact, the NBA’s constitution expressly prohibits the inclusion of players on the board of governors. Stakeholder recognition would be the first step for leagues toward achieving better governance in terms of democracy. After such recognition, mechanisms of representation and participation of these groups in league governance should be implemented. In this regard, it is suggested that these foundational documents must be modified, not only to allow the representation of stakeholders (coaches, players, referees, and fans) but also to promote it. Without modification, the recognition of the voice and vote of stakeholders regarding concrete aspects of governance would not be easy. It implies that MLB, NHL, NFL, and NBA stakeholders’ groups have a voice on their decision-making boards. The amendment of the constitution could aim at allowing stakeholders to be (better-)represented in decision-making processes, for example when ethical issues such as doping or match-fixing are addressed by rule changes, league investments, or governance mechanisms. While it is true that this would not substantially affect the balance of power immediately, it is the first step towards more democratic and inclusive practices.

5.2. Transparency: Publicity of Constitutions, Bylaws, and Internal Regulations

Concerning the availability of information, the discussion is focused on critical elements of the governance of both a sports organisation and conventional companies: publicity of constitutions, bylaws, and internal regulations. Publication of internal regulations can give stakeholders and society as a whole an idea of how leagues operate. Decision-making bodies can affect the professional dimensions and personal aspects of players, coaches, referees, and fans. The public domain of these foundational rules can give an idea of the leagues’ commitment to establishing clear rules for their operation and provide some certainty to those involved.

In the research process, access to internal regulations of the four professional leagues in North America, without exception, has been minimal. Even their most essential documents, their constitutions and bylaws, are not available to the public. Therefore, there was a need to conduct an exhaustive search of digital repositories of legal documents. For instance, for this research, the NBA and MLB’s constitutions were found in DocumentCloud, a platform that grants independent users access to primary source documents. This platform is part of the MuckRock Foundation, a non-profit organisation dedicated to promoting trust and transparency in organisations of distinct nature by publishing source documents on the open web.

The MLB’s constitution has been treated as an internal and secret text, which officially forms part of another document called The Official Professional Baseball Rules Book. However, when trying to access this rulebook, downloaded from MLB’s official website, it is not possible to find the section that refers to the governance structure of MLB. The NHL’s constitution is also not a document published by the league on its official website. The first reports that it had been released to the public domain were made in 2009 when a legal dispute over control of a member club forced the league to include its own constitution as part of the case and consequently made it publicly available (McGran 2009). This lends credence to the culture of secrecy that professional league constitutions typically possess and how it hinders the process of assessing their governance system. In the case of the NBA, reports indicate that the constitution was published in 2014 due to a scandal over racist comments made by one of the team owners. In order to apply the appropriate sanctions, the NBA commissioner decided to disclose the contents of the league’s constitution. According to Flynn (2014), this constituted an unprecedented display of transparency from the NBA. As with the previous leagues, it was not evident during this research that the NFL’s constitution and bylaws were available on any official web portals belonging to the league.

Compliance with the principle of transparency is often regulated by some legal systems, such as in European Union member states, where companies must disclose information on how they operate. However, this is not a widespread practice among companies in the US. According to the US Internal Revenue Service (2021), the office that administers and enforces federal tax regulations, bylaws are an organisation’s internal operating rule. From the legal perspective of the US institutions, this definition indicates that companies are not obliged to publish their bylaws because of their internal nature.

Strict adherence to the law is often an argument for establishing the limits of human and organisational behaviour. However, are legal provisions sufficient in determining best practices? Crane et al. (2019) maintain that the law might be understood as the minimum acceptable standards of conduct, but it does not explicitly cover every possible ethical issue in business. For those business issues that regulations cannot cover since they involve values in conflict, business ethics may offer some guidance to put in place good practices. Disclosure of internal corporate affairs could well fall into this grey area, as US regulations do not require companies to publish their internal regulations.

Professional sports leagues in North America are of interest to fans acting as consumers. Their management also impacts the welfare of employees (players, coaches, referees), and public funding has been part of the development of North American sport. Given this, it is suggested that these leagues voluntarily provide details of their internal workings to benefit the game and their stakeholders. Remarkably, the four professional leagues have maintained a culture of secrecy about foundational documents that explain operations, organisational structures, and internal decision-making processes that impact internal and external actors. Much of the game’s reputation rests on fans’ knowledge about how the leagues work. If there are suspicions of, for instance, doping, cheating, and threats to the integrity of athletes, it seems fair to communicate how decisions are made and who was involved.

Silver (2005, p. 16) maintains that stakeholders demand that organisations implement transparency not only ‘in the numbers they release but also in how they are run’. Schnackenberg and Tomlinson (2016) see transparency as a necessity not only from a normative perspective but also relating to pragmatic aspects of business, such as efficiency and gaining the trust of stakeholders. A culture of secrecy, therefore, runs the risk of damaging the reputation of the sports organisation among its main stakeholders and the gaining of public trust and support. Based on the above analysis, concerning the culture of secrecy surrounding the leagues’ internal regulations, it would be interesting to know if the leagues see commercial risks involved in publishing their internal regulations. If such risks do not exist, it is suggested that they dedicate a section of their websites to the publication of their constitutions, bylaws, and policies. It would create an environment of transparency where players, coaches, and spectators understand the protocols for response to specific problems by league authorities. It would help to provide a feeling that the organisation is determined to ensure that similar incidents will be addressed transparently and according to rules (e.g., addressing doping cases in the best interest of the fans and the health of the athletes, preventing cheating where the cheater is correctly sanctioned without any interests at stake, among others).

5.3. Accountability: Separation of Powers

The discussion centres around the first of the two components of accountability mentioned above: the separation of powers. It seeks to reflect on how the league structures respond to the principle of the separation of powers in light of the many powers that the commissioners have within the leagues, emphasising disciplinary attributions. The approach to the review of the separation of powers in professional leagues is based on constitutions and bylaws, as they set out the original powers of commissioners, boards, and committees. The constitutions confer the power to govern North American professional sports leagues upon the commissioner’s office. According to Lentze (1995), the creation of this super-powerful authority in 1920 obeyed the personal interests of the members, the ineffective MLB structure, and the ‘Chicago Black Sox’ scandal, which severely damaged the public confidence in the game and the league. To restore public faith in the integrity of the game, the owners replaced the commission with a single commissioner. Since then, any individual involved in the league is subject to the commissioner’s jurisdiction, bound by his/her decisions, with very discreet alternative instances of appeal and little power. The commissioner position was replicated from MLB to the other leagues with no significant changes.

Lentze (1995) states that commissioners retain disciplinary power, dispute resolution, and executive authority, for example appointing other officers and committees. According to Conrad (2009), league constitutions provide the commissioner’s extraordinary power to the extent that they can be judge, jury, and appeals court in a given disciplinary case. The constitutions secure a large number of powers for the commissioner and ensure that she/he remains in office for long periods. On average, each commissioner has been in office for fifteen years (McLin 2016).

Over the last few years, professional leagues have been an object of criticism due to how some disciplinary procedures have been handled. For instance, in Milwaukee American Ass’n v. Commissioner Landis, the court interpreted that it is deductible from the MLB’s constitution and collective bargaining agreement that the owners intend to grant the commissioner all the attributes of a ‘benevolent but absolute despot’ (Willisch 1993). The NFL’s commissioner does not only have the authority to discipline players for misconduct but also the capacity to review player appeals for penalties he or she imposed by appointing him- or herself over such grievances (Einhorn 2016). It means that commissioner decisions are final and non-appealable. For instance, NFL domestic violence policy infringements and cases of cheating such as ‘The Deflategate’ have been under the exclusive supervision of the commissioner’s office. As a result, they affect not only the integrity of the game but also the reputation of the league. Einhorn adds that these incidents have called the ability of the NFL commissioner into question, not only because of their individual capacities but also because of the absence of a fair appeals body composed of impartial arbitrators. According to Mondelli (2017), the NFL commissioner seems to impose a despotic government upon all other league members.

Because the team owners are also proprietors of the league as a whole, they appoint a figure who must not only defend their joint interests but also act in ‘the best interests of the game’. It is an expression that appears not infrequently in the constitutions of these leagues. Durney (1992) suggests that professional leagues’ primary disciplinary standard is ‘the best interest of the game’ clause, which is functional in supporting any decision from the commissioner’s office. The lack of clarity regarding the authority of ‘best interest’ offers a great deal of discretionary power to the commissioner, which has been used to extend the role’s powers and enforce excessive sanctions. The best interest of the game, integrity, and fairness have been motives for owners and commissioners to defend the almost absolute powers of the latter. Commissioners often turned to their ‘best interests’ powers to discipline players or another staff member within the leagues. Traditional experts in the field have often advocated for the benefits of this case. However, considering that much of the literature regarding professional league commissioners is from the 20th century, it is necessary to examine whether the ‘best interest of the game’ strategy is not contrary to contemporary principles of good governance in sport and therefore involves several risks.

For many years, professional players’ unions have negotiated collective agreements with professional leagues. One of the historical demands has been disciplinary proceedings being intervened in by external arbitration to guarantee stakeholders’ rights. During the first 50 years of MLB, the commissioner’s authority over all league discipline remained supreme. In 1970, the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) installed independent grievance arbitration into baseball’s collective bargaining agreement. They were reluctant to accept the idea that the commissioner, appointed and paid by the franchise owners, was an unbiased decision-maker in disputes where such owners were involved (Zimbalist 2007). This demand will eventually also be heard in the NBA and NHL. On the other hand, the NFL continues to give its commissioner absolute powers in these proceedings. Despite significant progress through collective bargaining agreements negotiated by players’ associations, concerns persist in the world of professional leagues regarding the independence of decision-makers in disciplinary processes. A disciplinary process should consider the rights of all parties involved. So far, our analysis suggests that this has not been the guiding criterion applied by the leagues to handle disciplinary issues. As stated before, commissioners respond to the interests of the game and the owners’ interests as they are subject to removal by the relevant board.

Geeraert (2013) suggests that a sound system of checks and balances in professional sports would imply separating disciplinary powers from those with executive responsibilities. In the context of North American professional sports leagues, it means that the current commissioner’s powers should be divided among several individuals or bodies. A first step in establishing a system of checks and balances in professional leagues is to stop using integrity as an explanation for arbitrariness. The vital function of the commissioner in protecting the integrity of the game has already been discussed. However, when we look at the nature of its second function, which is to protect the business interests of team owners, it can be even more problematic. This second responsibility raises a potential conflict of interest within the agency relationship between the owners and the commissioner. As the CEO of the league and owners’ employee, the commissioner is responsible for safeguarding the principals’ significant investments in the league (Willisch 1993). This mission mainly maintains labour harmony between teams and players, engages fans, and guarantees terrific television revenues. In regular companies, corporate functions would be performed by or under the mandate of the board of directors. By contrast, no further delegation of power is necessary according to professional leagues’ constitutions. While a board of directors oversees the actions of their CEO, the league’s owners do not oversee the actions of their commissioner (McLin 2016). If that is not enough leverage, the commissioner also has the authority to sanction owners for any misconduct. This would mean that a CEO can sanction board members. This ability to sanction league members derives from the best interest of the game clauses and conflicts with their role of defending the owners’ best interests. The employee–employer relationship does not allow the commissioner to exercise these powers freely. Any decision that goes against the interests of a group of owners could mean his/her removal from office.

Many decision-making processes in professional leagues imply the sole discretion of the commissioner. From the perspective of business ethics and good governance principles in sports, such concentration of power in the commissioner and conflicting interests involved in an agency relationship do not correspond to good practices in the business world nor sports organisations. Adopting an alternative structure with elements of the corporate culture and satisfying demands from the sports industry would mitigate some of the negative consequences of the current model.

In addition to the apparent governance problems arising from the current conception of the commissioner and his or her relationship with other governing bodies of the professional leagues, some scholars in the field have proposed alternative structures to the existing one (Willisch 1993; Lentze 1995). Given the particularities of professional sports and their corporate nature, it would seem appropriate to implement a hybrid system that addresses various interests, one that is fair to the various stakeholders and improves the business efficiency of these leagues. As already proposed, the need to separate the executive arm from the disciplinary arm is paramount. The hybrid model suggested by these authors involves a CEO taking full ownership of corporate decisions and preserving team proprietors’ interests. It also contemplates the commissioner’s role in the hands of a different individual, who protects the integrity of the game with no concerns about independence from the owners. For a clear understanding of this separation of roles, Willisch (1993) distinguishes between the ‘best Interest of the game’ and ‘the best economic interest’. For the former, it is appropriate to rethink the source of the commissioner’s power. Protecting the game requires absolute independence from economic factors and not the mere declaration of autonomy and moral status of the commissioner. For the latter, taking the fundamentals of the CEO position seems suitable for continuing to manage the economic side of the leagues.

Although most of the criticism of power concentration may come from the governance view of sport governing organisations, calls for deconcentrating power within the corporate culture are becoming more prevalent. If professional sports leagues in North America intend to implement best practices as a sporting organisation but also as a company in the following years, then they should undoubtedly consider separating their executive arm from the disciplinary arm as a first step. While it is true that the professional leagues have not suffered from outside intervention by the courts, the adoption of these measures will help these leagues remain autonomous. At the same time, it will improve their accountability practices, which is a growing demand in the US for private entities and sports organisations worldwide.

6. Conclusions and Implications

By linking (good) governance to rational choice theory, Geeraert (2022) holds that organisations that fail to implement some form of transparency, accountability, and democracy run the risk that unconstrained self-interest and limited access to information will lead to governance failures in organisations. Our critical analysis identified several areas in which North American professional sports leagues may be exposed to such a risk. It can be concluded that changes in the governance structure of North American professional sports leagues have been essentially determined by economic motivations, in part to preserve monopoly power. As a result, it has been conducive to an utterly self-governed system with predominantly corporate features and some characteristics typical of sports organisations. The analysis involved making visible concrete aspects of organisational structures and practices of the leagues, examining them in terms of selected principles of (good) governance. Based on our analysis, we can identify some risk management-related recommendations for each of the three principles analysed.

In terms of democracy, professional leagues have not recognised stakeholder interests in decision-making processes, despite clear evidence that their policies affect interests beyond those of the team owners. For this reason, it is suggested to promote reforms to those constitutions and bylaws whose spirit is that of the early twentieth century when the leagues were founded. It implies transcending shareholder supremacy and ensuring that representatives of these stakeholders (players, coaches, referees, among others) have a position on decision-making boards to avoid the risk of continued discomfort among affected groups. Furthermore, it would contribute to meeting social demands for stakeholder participation and representation towards companies and sports organisations, which would positively impact the leagues’ reputation and establish confident perceptions of their work culture.

In terms of transparency, the research process itself revealed the culture of secrecy surrounding the governance of the four professional leagues. Specifically, one of the findings was that their internal regulations, such as constitutions and bylaws, policies and disciplinary measures are not in the public domain. Lax regulation in the US is often an excuse for companies not to disclose their internal information, but it has been shown that the laws are only minimum acceptable standards of conduct. In this regard, both good governance principles and business ethics can guide the implementation of good practices. Given the interests of employees and the social interest in sport, leagues should contemplate the business risks of publishing their constitutions, bylaws, policies, and procedures on their websites. Without jeopardising the commercial operations of the league, making this information available to stakeholders would help create an environment of transparency and certainty on integrity matters specific to sports and business affairs.

In terms of accountability, the salient aspect was the primacy of the commissioner’s role in the governance of the leagues. This, in turn, raised ethical concerns involving the high concentration of power in this figure and an evident conflict of interest due to the atypical commissioner–team owners’ relationship. Thus, a first approach to solving this problem would be the separation of disciplinary and executive powers to avoid the risk of potential conflicts of interest. While the commissioner watches over the integrity of the game, a CEO could govern the league in business matters. In this way, the best interests of the game would be separated from the best economic interests of the owners, which are not always aligned. It would address concerns arising from lack of independence when resolving disputes or applying disciplinary measures and contribute to better-addressing business challenges.

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

We have based our analysis on concrete examples of detected shortcomings in each of the three principles. It is important to note though, that these examples are only part of a longer list of shortcomings in each of the three areas. In our analysis, we came across a couple of other cases that would be worth investigating further (see Figure 1), yet the scope of the article and length restrictions did not allow us to address these in detail. These cases include a lack of a diversity and inclusion in board compositions (democracy). In terms of gender, for instance, after more than one hundred years since the first of these professional leagues was founded, all the commissioners who have held office have been white men. Furthermore, none of the thirteen MLB franchise owners (Baseball Reference 2020) and none of the thirty-one team representatives on the NHL Board of Governors are women (NHL 2021). Racial underrepresentation is even more eye-catching as the significant percentage of players, coaches, and referees of Latin and African American origin in the MLB, NFL, and NBA is not reflected at all in the composition of team owners. Furthermore, regarding transparency, we identified a complete lack of disclosure of financial statements. Even though professional leagues are not public companies, we would argue that the disclosure of such companies may well be implemented for the sake of good governance. In terms of accountability, we would like to highlight a lack of management supervision and potential conflicts due to the agency relationship between the owners and the commissioner. Given these examples, we believe that further research should explore these issues as well as others to increase awareness.

More generally, one significant limitation is that we conducted our analysis only on the basis of publicly available information. As Thompson et al. (2022) point out, such a procedure skews findings in favour of organisations that are more externally transparent. Furthermore, the design of our study does not provide an internal perspective looking into how the leagues internally deal with the mentioned issues. According to Thompson et al. (2022) and Pielke et al. (2019), this is a common shortcoming of most research on governance principles in organisations. Our contribution can thus only be a first step in exploring these fields. Therefore, we echo these authors’ suggestion of conducting empirical studies that adopt more sophisticated qualitative (e.g., observations, interviews) or quantitative (e.g., questionnaires) methods to obtain direct internal data from organisations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M. and M.S.; Methodology, N.M. and M.S.; Validation, N.M. and M.S.; Formal analysis, N.M.; Investigation, N.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.M. and M.S.; Writing—review and editing, N.M. and M.S.; Supervision, N.M. and M.S.; Project administration, N.M. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alm, Jens. 2013. Good Governance in International Non-Governmental Sports Organisations: An Empirical Study on Accountability, Participation and Executive Body Members in Sport Governing Bodies. Copenhagen: Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Andreff, Wladimir, and Paul Staudohar. 2002. European and US sports business models. In Transatlantic Sport. Edited by Carlos P. Barros, Muradali Ibrahimo and Stephan Szymanski. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Augelli, Chelsea, and Tamara Kuennen. 2018. Domestic Violence & Men’s Professional Sports: Advancing the Ball. The University of Denver Sports & Entertainment Law Journal 21: 27–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Kenneth. 1994. Typologies and Taxonomies: An Introduction to Classification Techniques. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Baseball Reference. 2020. List of Major League Baseball Principal Owners. Available online: https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/List_of_Major_League_Baseball_principal_owners (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Blair, Roger D. 2011. Sports Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blount, Justin. 2015. Creating a stakeholder democracy under existing corporate law. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law 18: 365–417. [Google Scholar]

- Bovens, Mark. 2007. Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. European Law Journal 13: 447–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyninckx, Hans. 2012. Sport Governance—Between the Obsession with Rules and Regulation and the Aversion to Being Ruled and Regulated. In Sports Governance, Development and Corporate Responsibility. Edited by Barbara Segaert, Mark Theeboom, Christiane Timmerman and Bart Vanreusel. New York: Routledge, pp. 107–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chappelet, Jean-Loup, and Michael Mrkonjic. 2013. Basic Indicators for Better Governance in International Sport (BIBGIS): An Assessment Tool for International Sport Governing Bodies. (No. 1/2013). Lausanne: IDHEAP. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance. 1992. Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance. Available online: http://cadbury.cjbs.archios.info/report (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Congressional Research Service. 2011. Congressionally Chartered Nonprofit Organisations (“Title 36 Corporations”): What They Are and How Congress Treats Them. Available online: https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RL30340.html (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Conklin, Michael. 2020. There’s No Lawsuit in Baseball: Houston Astros’ Liability for Sign Stealing. Mississippi Sports Law Review 9: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, Mark. 2009. The Business of Sports: A Primer for Journalists. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, Andrew, Dirk Matten, Sarah Glozer, and Laura J. Spence. 2019. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Robert A. 2020. On Democracy. New Haven: Yale UP. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Bria L. 2018. Put Me In Coach: Recognizing NBA Players’ Need for Legal Protection as Stakeholders in the League and Increased Participation in Governance. The Journal of Corporation Law 43: 939–64. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, Gjalt, and Arjen Van Witteloostuijn. 2004. Successful corporate democracy: Sustainable cooperation of capital and labor in the Dutch Breman Group. Academy of Management Perspectives 18: 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durney, Jeffrey A. 1992. Fair or Foul: The Commissioner and Major League Baseball’s Disciplinary Process. Emory Law Journal 41: 581–632. [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn, Eric L. 2016. Between the Hash Marks: “The Absolute Power the NFL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement Grants Its Commissioner”. Brooklyn Law Review 82: 393–428. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, Joe. 2014. NBA Releases Its Formerly Secret Constitution. Available online: https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2045950-nba-releases-its-formerly-secret-constitution (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Flynn, Michael A., and Richard J. Gilbert. 2001. The analysis of professional sports leagues as joint ventures. The Economic Journal 111: F27–F46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, Rodney. 2000. European and North American sports differences (?). Scottish Journal of Political Economy 47: 431–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssbaeck, J., and L. Oxelheim, eds. 2014. The multifaceted concept of transparency. In The Oxford Handbook of Economic and Institutional Transparency. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Milton. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Ray. 1956. Attitudes on Corporate Democracy—A Critical Analysis. Northwestern University Law Review 51: 310–36. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraert, Arnout. 2013. The Governance Agenda and Its Relevance for Sport: Introducing the Four Dimensions of the AGGIS Sports Governance Observer. Aarhus: Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraert, Arnout. 2018. Sports Governance Observer 2018. An Assessment of Good Governance in Five International Sports Federations. Aarhus: Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraert, Arnout. 2022. A rational choice perspective on good governance in sport: The necessity of rules of the game. In Good Governance in Sport. Critical Reflections. Edited by Arnout Geeraert and Frank van Eekeren. London: Routledge, pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraert, Arnout, Jens Alm, and Michael Groll. 2014. Good governance in international sport organisations: An analysis of the 35 Olympic sport governing bodies. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 6: 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, Kent. 1997. The place of workers in corporate law. Boston College Law Review 39: 283–327. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Anne. 2004. Rethinking Homophobia in Sports: Legal Protections for Gay and Lesbian Athlete and Coaches. DePaul Journal of Sports Law and Contemporary Problems 2: 264–92. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Nadelle. 2014. What is the NBA. Marquette Sports Law Review 25: 101–28. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, Greg, Kathleen M. MacQueen, and Emily E. Namey. 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, Maarten A. 1997. The Politics of Environmental Discourse. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Ian, and Ping C. Lee. 2004. Governance and ethics in sport. In The Business of Sport Management. Edited by Simon Chadwick and John Beech. Harlow: Pearson Education, pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, Cory. 2016. American Sports in an Age of Consumption: How Commercialization Is Changing the Game. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Christopher. 2010. Accountability and transparency: Siamese twins, matching parts, awkward couple? West European Politics 33: 989–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internal Revenue Service. 2021. Exempt Organisation—Bylaws. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/other-non-profits/exempt-organisation-bylaws (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Jackson, Gregory, Martin Höpner, and Antje Kurdelbusch. 2004. Corporate Governance and Employees in Germany: Changing Linkages, Complementarities, and Tensions. RIETI Discussion Paper Series 04-E-008. Tokyo: The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI). [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Katharine. V. 2011. Towards a Stakeholder-Shareholder Theory of Corporate Governance: A Comparative Analysis. Hastings Business Law Journal 7: 309–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jozsa, Frank P. 2010. National Basketball Association, The: Business, Organisation And Strategy. Singapore: World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Kristol, Irving. 1975. Corporate capitalism in America. The Public Interest 41: 124–41. [Google Scholar]

- Leeds, Michael A., Peter Von Allmen, and Victor A. Matheson. 2018. The Economics of Sports. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lentze, Gregor. 1995. The legal concept of professional sports leagues: The commissioner and an alternative approach from a corporate perspective. Marquette Sports Law Review 6: 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Longley, Neil. 2013. An Absence of Competition: The Sustained Competitive Advantage of the Monopoly Sports Leagues. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Marcano, Arturo J., and David P. Fidler. 1999. The globalization of baseball: Major League Baseball and the mistreatment of Latin American baseball talent. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 2: 511–77. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbins, Mathew D., and Thomas Schwartz. 1984. Congressional oversight overlooked: Police patrols versus fire alarms. American Journal of Political Science 28: 165–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGran, Kevin. 2009. NHL Spills Its Secrets in Court. The Toronto Star. June 7. Available online: https://www.thestar.com/sports/hockey/2009/06/07/nhl_spills_its_secrets_in_court.html (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- McLin, Ian A. 2016. Going…Going…Public: Taking a United State Professional Sports League Public. William & Mary Business Law Review 8: 545–76. [Google Scholar]

- McNamee, Michael J., and Scott Fleming. 2007. Ethics audits and corporate governance: The case of public sector sports organisations. Journal of Business Ethics 73: 425–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittag, Jürgen, and Ninja Putzmann. 2013. Reassessing the democracy debate in sport alternatives to the one-association-one-vote-principle? In Action for Good Governance in International Sports Organisations. Edited by J. Alms. Copenhagen: Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies, pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mondelli, Michael. 2017. The Roger Goodell Standard: Is Commissioner Authority Good for Sports. Seton Hall Law Legislative Journal 42: 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- National Hockey League (NHL). 2021. Board of Governors. Available online: https://records.nhl.com/organization/board-of-governors (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- OECD. 2015. G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/g20-oecd-principles-of-corporate-governance-2015_9789264236882-en (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Pielke, Roger, Spencer Harris, Jared Adler, Sara Sutherland, Richard Houser, and Jackson McCabe. 2019. An evaluation of good governance in US Olympic sport national governing bodies. European Sport Management Quarterly 20: 480–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggin, Joe, Steven J. Jackson, and Malcom Lewis. 2009. Knowledge, power and politics: Contesting evidence based’ national sport policy. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 44: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, Geoffrey C. 2012. Suicide, Concussions, and the NFL. FIU Law Review 8: 123–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado, Samuel O. 1998. Viva Baseball!: Latin Major Leaguers and Their Special Hunger. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Alasdair. 2006. Blacked Out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosentraub, Mark S. 2000. Governing sports in the global era: A political economy of Major League Baseball and its stakeholders. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 8: 121–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schnackenberg, Andrew K., and Edward C. Tomlinson. 2016. Organisational transparency: A new perspective on managing trust in organisation-stakeholder relationships. Journal of Management 42: 1784–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 1997. A survey of corporate governance. The Journal of Finance 52: 737–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shropshire, Kenneth L. 2004. Minority issues in contemporary sports. Stanford Law & Policy Review 15: 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, David. 2005. Creating transparency for public companies: The convergence of PR and IR in the post-Sarbanes-Oxley marketplace. Public Relations Strategist 11: 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm L., and Juliet Corbin. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory, Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski, Stefan. 2003. The economic design of sporting contests. Journal of Economic Literature 41: 1137–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Ashley, Erik L. Lachance, Milena Parent, and Russell Hoye. 2022. A systematic review of governance principles in sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, [Online First version]; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International. 2021. Good Governance in Sport Organisations. Available online: https://www.transparency.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Publikationen/2021/GoodGovernance-in-Sports-Organisations.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Van Bottenburg, Maarten. 2011. Why Are the European and American Sports Worlds So Different? Path-Dependence in European and American Sports History. In Sport and the Transformation of Modern Europe. Edited by Alan Tomlinson, Christopher Young and Richard Holt. New York: Routledge, pp. 217–37. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, Julian. 2010. Shareholder ownership and primacy. University of Illinois Law Review 2010: 897–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Willisch, Michael J. 1993. Protecting the Owners of Baseball: A Governance Structure to Maintain the Integrity of the Game and Guard the Principals’ Money Investment. Northwestern University Law Review 88: 1619–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Roberta F. 2010. Conflicting Anti-Doping Laws in Professional Sports: Collective Bargaining Agreements v. State Law. Seattle University Law Review 34: 1605–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbalist, Andrew. 2002. Competitive balance in sports leagues: An introduction. Journal of Sports Economics 3: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbalist, Andrew. 2007. In the Best Interests of Baseball: The Revolutionary Reign of Bud Selig. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).