Does the Croatian Stock Market Have Seasonal Affective Disorder?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Research

3. Methodology Description

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Data Description

4.2. Initial Results

4.3. Robustness Checking

4.4. Simple Investing Strategies Simulation

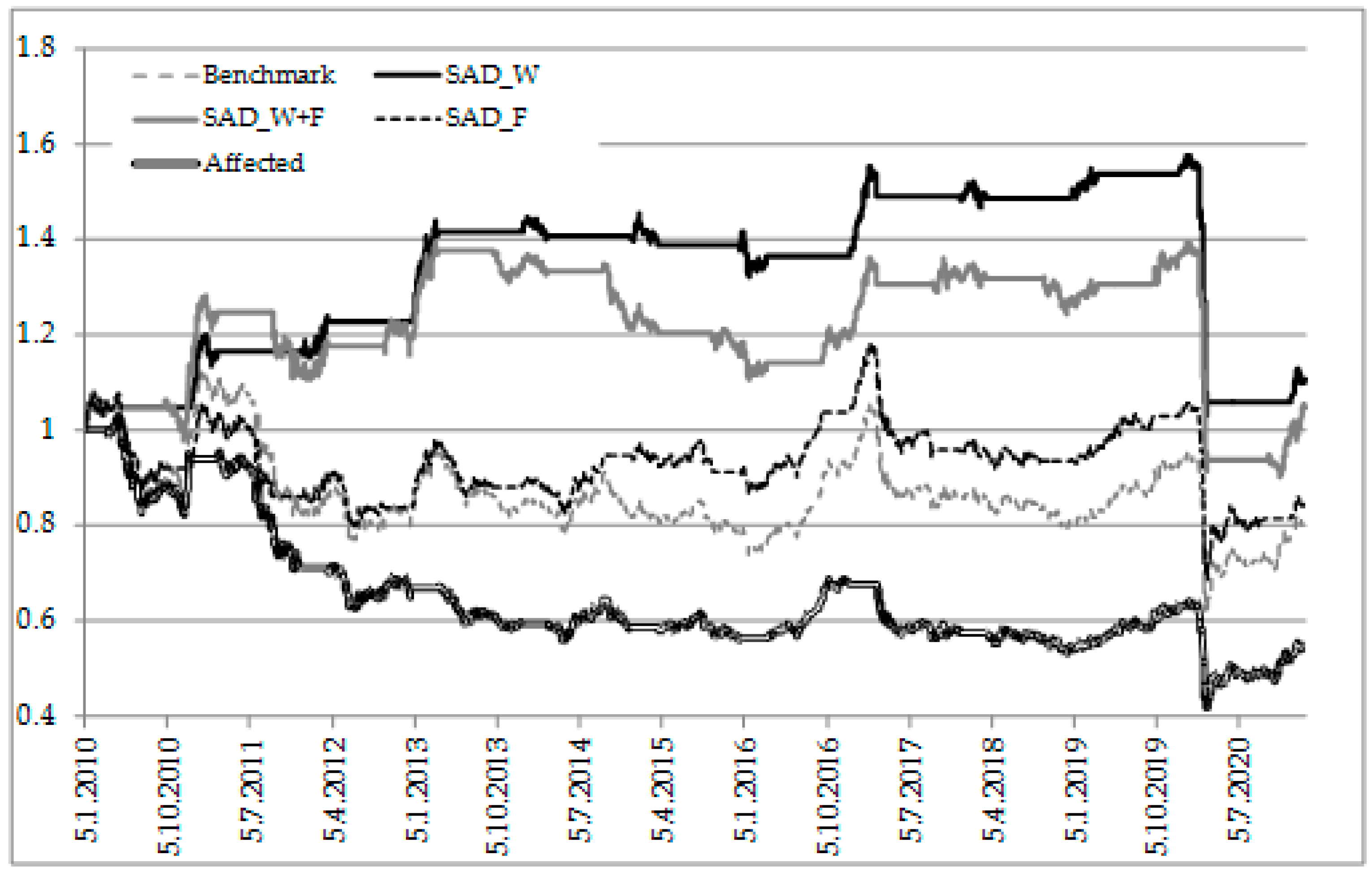

- (i)

- First strategy is the SAD_W, in which the investor uses the contrarian strategy where he buys the stock market index before the winter time and holds it during the winter. When spring comes, he sells the index and holds the money until the new winter season arrives.

- (ii)

- Second strategy is SAD_W+F, in which investor uses contrarian strategy again (as previous one), but adds the information about asymmetric effect of the fall time. Thus, when the variable Fall is not equal to zero, then the investor does not sell the index, as returns fall additionally. Opposite is true for Fall being equal to zero.

- (iii)

- Third strategy is SAD_F, in which the investor uses the contrarian strategy, in which he buys the index when the value of Fall is not equal to zero due to lower returns, and holds the index until it is ready to be sold (when the value of Fall is zero).

- (iv)

- Fourth strategy is simulated based on those investors who are affected by the SAD effects and do the wrong thing, sell when the returns are expected to rise, and buy when the returns are expected to fall. This is called “affected”.

4.5. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agrawal, Anup, and Kishore Tandon. 1994. Anomalies or illusions? Evidence from stock markets in eighteen countries. Journal of International Money and Finance 13: 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baele, Lieven, Geert Bekaert, and Larissa Schäfer. 2015. An Anatomy of Central and Eastern European Equity Markets. Columbia Business School Working Paper, No. 15–71. Singapore: Columbia Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Malcom, and Jeffery Wurgler. 2006. Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. The Journal of Finance 61: 1645–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Malcom, and Jeffery Wurgler. 2007. Investor sentiment in the stock market. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21: 129–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcilar, Mehmet, Rangan Gupta, and Clement Kyei. 2018. Predicting stock returns and volatility with investor sentiment indices: A reconsideration using a nonparametric causality in quantiles test. Bulletin of Economic Research 70: 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchit, Azilawati, Sazali Abidin, Sophyafadeth Lim, and Fareiny Morni. 2020. Investor Sentiment, Portfolio Returns, and Macroeconomic Variables. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbić, Tajana. 2010. Testiranje slabog oblika hipoteze efikasnog tržišta na hrvatskom tržištu dionica (Testing the weak form of efficient market hypothesis on Croatian stock market). Proceedings of the Faculty of Economics and Business in Zagreb. Zbornik Ekonomskog fakulteta u Zagrebu 8: 155–72. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, Robert Joseph, Jose Ursua, and Joanna Weng. 2020. The coronavirus and the great influenza pandemic: Lessons from the “Spanish Flu” for the coronavirus’s potential effects on mortality and economic activity. National Bureau Economic Research, w26866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathia, Deven, and Don Bredin. 2013. An examination of investor sentiment effect on G7 stock market returns. The European Journal of Finance 19: 909–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, Geert, and Campbell Harvey. 1995. Time-varying world market integration. Journal of Finance 50: 403–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Melanie, and Jason Wei. 2005. Stock market returns: A note on temperature anomaly. Journal of Banking & Finance 296: 1559–73. [Google Scholar]

- Concetto, Chiara Limongi, and Francesco Ravazzolo. 2019. Optimism in Financial Markets: Stock Market Returns and Investor Sentiments. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- De Long, Bradford, Andrei Shleifer, Lawrence Summers, and Robert Waldmann. 1990. Noise trader risk in financial markets. Journal of Political Economy 98: 703–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, Jaap, Ligaya Butalid, Lars Penke, and Marcel van Aken. 2008. The effects of weather on daily mood: A multilevel approach. Emotion 85: 662–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolvin, Steven, and Mark Pyles. 2007. Seasonal affective disorder and the pricing of IPOs. Review of Accounting and Finance 62: 214–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolvin, Steven, Mark Pyles, and Q. Wu. 2009. Analysts Get SAD Too: The Effect of Seasonal Affective Disorder on Stock Analysts’ Earnings. The Journal of Behavioral Finance 10: 214–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, Michael, and Brian M. Lucey. 2005. Weather, Biorhythms, Beliefs and Stock Returns—Some Preliminary Irish Evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis 143: 337–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, Michael, and Brian Lucey. 2008. Robust Global Mood Influences in Equity Pricing. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 182: 145–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragotă, Victor, and Elena Ţilică. 2014. Market efficiency of the Post Communist East European stock markets. Central European Journal of Operations Research 22: 307–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Ding, Ronald Gunderson, and Xiaobing Zhao. 2016. Investor sentiment and oil prices. Journal of Asset Management 17: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene Francis. 1965. The Behavior of Stock-Market Prices. Journal of Business 64: 34–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene Francis. 1970. Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work. The Journal of Finance 252: 383–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Paulo. 2018. Long-range dependencies of Eastern European stock markets: A dynamic detrended analysis. Physica A 505: 454–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, Joseph. 1995. Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin 117: 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gakhovich, Alexander. 2011. The Holiday Effect in the Central and Eastern European Financial Markets. Dissertation, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Ian, Mark Kamstra, and Lisa Kramer. 2005. Winter Blues and Time Variation in the Price of Risk. Journal of Empirical Finance 12: 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosten, Lawrence, Ravi Jagannathan, and David Runkle. 1993. On the relation between the expected value and the volatility of the nominal excess returns on stocks. The Journal of Finance 48: 1779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golab, Anna, David Allen, and Robert Powell. 2015. Aspects of Volatility and Correlations in European Emerging Economies. In Emerging Markets and Sovereign Risk. Edited by Finch Nigel. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Grable, John, and Michael Roszkowski. 2008. The influence of mood on the willingness to take financial risks. Journal of Risk Research 11: 905–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, Fatma, and Ezzeddine Abaoub. 2011. Winter Blues, Investor Mood and Stock Market Returns: Evidence from the Tunisian Stock Exchange. Journal of Applied Finance 172: 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- He, Pinglin, Yulong Sun, Ying Zhang, and Tao Li. 2020. COVID–19′s Impact on Stock Prices Across Different Sectors—An Event Study Based on the Chinese Stock Market. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 56: 2198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heininen, Polina, and Vesa Puttonen. 2008. Stock Market Efficiency in the Transition Economies through the Lens of Calendar Anomalies. Paper presented at the 10th Biannual EACES Conference, Moscow, Russia, August 28. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer, David, and Tyler Shumway. 2003. Good day sunshine: Stock returns and the weather. The Journal of Finance 583: 1009–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Dashan, Fuwei Jiang, Jun Tu, and Goufu Zhou. 2014. Investor sentiment aligned: A powerful predictor of stock returns. Review of Financial Studies 28: 791–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, Alice, and Robert Patrick. 1983. The effect of positive feelings on risk taking: When the chips are down. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 31: 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, Alice, Thomas Nygren, and Gregory Ashby. 1988. Influence of positive affect on the subjective utility of gains and losses: It is just not worth the risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55: 710–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, Ben, and Wessel Marquering. 2008. Is it the weather? Journal of Banking & Finance 324: 526–40. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Eric, and Amos Tversky. 1983. Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 451: 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. Econometrica 472: 263–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamstra, Mark, Lisa Kramer, and Maurice Levi. 2002. Losing Sleep at the Market. American Economic Review 924: 1251–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kamstra, Mark, Lisa Kramer, and Maurice Levi. 2003. Winter Blues: A SAD Stock Market Cycle. American Economic Review 931: 324–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamstra, Mark, Lisa Kramer, and Maurice Levi. 2008a. Opposing Seasonalities in Treasury Versus Equity Returns. Working paper. Toronto: University of Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Kamstra, Mark, Lisa Kramer, Maurice Levi, and Wermers Russ. 2008b. Seasonal Asset Allocation: Evidence from Mutual Fund Flows. Working paper. Toronto: University of Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Kamstra, Mark, Lisa Kramer, and Maurice Levi. 2009. Is it the weather? Comment. Journal of Banking & Finance 333: 578–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kliger, Doron, and Ori Levy. 2008. Mood Impacts on Probability Weighting Funcitons: Large-Gamble Evidence. Journal of Socio-Economics 374: 1397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Lisa, and Mark Weber. 2011. This is Your Portfolio on Winter: Seasonal Affective Disorder and Risk Aversion in Financial Decision Making. Social Psychological and Personality Science 3: 193–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, Nikolaos. 2019. A Survey on Efficiency and Profitable Trading Opportunities in Cryptocurrency Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2008. Systemic Banking Crises: A New Database. IMF Working Paper WP/08/224. Washington, DC: IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Lakonishok, Josef, and Seymour Smidt. 1988. Are seasonal anomalies real? A ninety year perspective. Review of Financial Studies 1: 403–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Wayne, Christine Jiang, and Daniel Indro. 2002. Stock market volatility, excess returns, and the role of investor sentiment. Journal of Banking & Finance 26: 2277–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Kin, and Serena Wu. 2018. The Impact of Seasonal Affective Disorder on Financial Analysts. The Accounting Review 93: 309–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, George, Elke Weber, Christopher Hsee, and Ned Welch. 2001. Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin 1272: 267–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliaropulos, Dimitrios, and Richard Priestley. 1999. Mean reversion in Southeast Asian stock markets. Journal of Empirical Finance 6: 355–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, Pece Andrea, Ludisan Emilia Anuta, and Mutu Simona. 2013. Testing the long range-dependence for the Central Eastern European and the Balkans stock markets. Annals of the University of Oradea, Economic Science Series 22: 1113–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mayoclinic. 2018. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/seasonal-affective-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20364651 (accessed on 13 July 2018).

- Mehra, Rajnish, and Raaj Sah. 2002. Mood fluctuations, projection bias, and volatility of equity prices. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 26: 869–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, Robert. 1973. An Intertemporal Capital Asset Pricing Model. Econometrica 415: 867–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Edward. 1988. Why a weekend effect. The Journal of Portfolio Management 14: 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević Avdalović, Snežana, and Ivan Milenković. 2017. January effect on stock returns: Evidence from emerging Balkan equity markets. Industrija 45: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance. 2021. Available online: http://www.mfin.hr (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Muller, Luisa, Dirk Schiereck, Marc Simpson, and Christian Voigt. 2009. Daylight saving effect. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 192: 127–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgea, Aurora. 2016. Seasonal affective disorder and the Romanian stock market. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 291: 177–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Naik, Pramod Kumar, and Puja Padhi. 2016. Investor sentiment, stock market returns and volatility: Evidence from National Stock Exchange of India. International Journal of Management Practice 9: 213–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinegar, Michael. 2002. Losing sleep at the market: Comment. American Economic Review 92: 1251–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanov, Boris, and Aleksandra Marcikić. 2017. Bootstrap testing of trading strategies in emerging Balkan stock markets. E&M Economics and Management 20: 103–19. [Google Scholar]

- Roecklein, Kathyrin, and Kelly Rohan. 2005. Seasonal Affective Disorder An overview and Update. Psychiatry 2005: 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, Norman. 1998. Winter Blues: Seasonal Affective Disorder-What It Is and How to Overcome It. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, Norman. 2012. Winter Blues: Everything You Need to Know to Beat Seasonal Affective Disorder. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, Norman, David Sack, Christiansan Gillin, Alfred Lewy, Frederick Goodwin, Yolande Davenport, Peter Mueller, David Newsome, and Thomas Wehr. 1984. Seasonal affective disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry 41: 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupande, Lorriane, Hilary Tinotenda Muguto, and Paul-Francois Muzindutsi. 2019. Investor sentiment and stock return volatility: Evidence from the Johannesburg stock exchange. Cogent Economics and Finance 7: 1600233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Edward. 1993. Stock prices and Wall Street weather. American Economic Review 835: 1337–45. [Google Scholar]

- Šego, Boško, and Tihana Škrinjarić. 2018. Quantitative research of Zagreb stock exchange—literature overview for the period from establishment until 2018. Economic Review (Ekonomski Pregled) 69: 655–734. [Google Scholar]

- Shleifer, Andrei. 1999. Inefficient Markets: An Introduction to Behavioral Finance. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Škrinjarić, Tihana. 2012. The calendar effects on stock returns Kalendarski učinci u prinosima dionica. Economic Review (Ekonomski Pregled) 63: 651–78. [Google Scholar]

- Škrinjarić, Tihana. 2018. Testing for Seasonal Affective Disorder on selected CEE and SEE stock markets. Risks 6: 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrinjarić, Tihana. 2020. Dynamic portfolio optimization based on grey relational analysis approach. Expert Systems with Applications 147: 113207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrinjarić, Tihana, and Zrinka Orlović. 2020. Economic policy uncertainty and stock market spillovers: Case of selected CEE markets. Mathematics 8: 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrinjarić, Tihana, Zrinka Lovretin Golubić, and Zrinka Orlović. 2020. Empirical analysis of dynamic spillovers between exchange rate return, return volatility and investor sentiment. Studies in Economics and Finance 2020: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Graham. 2012. The changing and relative efficiency of European emerging stock markets. European Journal of Finance 18: 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šonje, Velimir, Denis Alajbeg, and Zoran Bubaš. 2011. Efficient market hypothesis: Is the Croatian stock market as (in)efficient as the U.S. market. Financial Theory and Practice 35: 301–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanescu, Razvan, and Ramona Dumitriu. 2011. The SAD Cycle for the Bucharest Stock Exchange. MPRA Working paper No. 41889. Munich: University Library of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, Ovidiu, and Delia-Elena Diaconasu. 2011. An Examination of the Calendar Anomalies on Emerging Central and Eastern European Stock Markets. Recent Researchers in Applied Economics. Conference Paper: 3rd World Multiconference on Applied Economics, Business and Development. Available online: http://www.wseas.us/e-library/conferences/2011/Iasi/AEBD/AEBD-19.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Stoitsova-Stoykova, Ani. 2017. Relationship Between Public Expectations and Financial Market Dynamics in South-East Europe Capital Markets. Economic Alternatives 2: 237–50. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Chei-Wei, Xu-Yu Cai, and Ran Tao. 2020. Can stock investor sentiment be contagious in China. Sustainability 12: 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Hulbert. 1980. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 48: 817–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Cheng. 2016. Are UK Financial Markets SAD? A Behavioural Finance Analysis. Ph.D. thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, Quianwei, Tahir Yousaf, Qurat ul Ain, Yasmeen Akhtar, and Muhammad Shahid Rasheed. 2019. Stock Investment and Excess Returns: A Critical Review in the Light of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12: 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Hai-Chin Yu, Michael S. Pagano, and Chia-Yi Wu. 2011. Intraday Returns and Weekday Effects in the Dow Jones and Nasdaq Stock Indexes. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics 68: 14–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Dayong, Min Hu, and Qiang Ji. 2020. Financial Markets Under the Global Pandemic of COVID-19. Finance Research Letters. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagreb Stock Exchange. 2021. Available online: http://www.zse.hr (accessed on 10 February 2021).

| Authors (year) | Market, Data | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Kamstra et al. (2003) | US, Sweden, UK, Germany, Canada, New Zealand, Japan, Australia, South Africa; 1928–2003 | Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) effects exist, greater effects when further from the equator |

| Garrett et al. (2005) | US, UK, Japan, Sweden, New Zealand, and Australia; 1962–2000 | SAD effects exist |

| Jacobsen and Marquering (2008) | 48 countries; 1970–2004 | SAD effects insignificant |

| Kamstra et al. (2009) | Replication of Jacobsen and Marquering (2008) | SAD effects found, problems of 2008 paper found |

| Dolvin et al. (2009) | US, 1998–2004 | Analysts’ forecasts are under SAD effects |

| Stefanescu and Dumitriu (2011) | Romania, 2002–2011 | SAD effects found, but no control variables included |

| Hammami and Abaoub (2011) | Tunis, 1998–2008 | No SAD effects, Tunis is close to the equator |

| Lo and Wu (2018) | US, 1998–2004 | Pessimistic analyst forecasts when SAD effects hold |

| Murgea (2016) | Romania, 2000–2014 | SAD effects found in every subsample (before, during and after 2008 crisis) |

| Škrinjarić (2018) | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Romania, and Ukraine, 2010–2018 | 6 out of 11 (Croatia included) had SAD effects, only return series observed |

| Descriptive Statistics | Return | Excess Return |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | −4.37 × 10−5 | −0.009 |

| Standard deviation | 0.0075 | 0.0135 |

| Min | −0.1073 | −0.1076 |

| Max | 0.0856 | 0.0626 |

| Skewness | −1.7526 | −1.2474 |

| Kurtosis | 41.477 | 6.498 |

| AR(5) | 94.474 (0.000) | 69.08 (0.000) |

| ARCH(5) | 934.32 (0.000) | 53.09 (0.000) |

| Parameter/Diagnostics | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.61 × 10−5 (0.0002) | 9.37 × 10−5 (0.0002) | - | - | |

| 0.0003 (0.0001) ** | 0.0004 (0.0002) *** | - | - | |

| −0.0018 (0.0004) *** | −0.002 (0.0004) ** | - | - | |

| 0.0017 (0.001) * | 0.0014 (0.0012) | - | ||

| −0.0003 (0.0002) * | - | - | ||

| −0.0033 (0.003) | −0.0035 (0.0032) | |||

| - | - | 3.45 (3.57) | - | |

| - | - | 1.89 × 10−6 (3.89 × 10−7) *** | - | |

| - | - | 0.096 (0.015) *** | - | |

| - | - | 0.859 (0.021) *** | - | |

| - | - | - | −0.052 (0.025) ** | |

| - | - | - | 0.055 (0.019) *** | |

| - | - | - | −0.038 (0.024) * |

| Parameter/Parameter | ||

|---|---|---|

| Original (from Table 2) | 0.0004 (0.0002) *** | −0.0003 (0.0002) * |

| With GARCH specification | 0.0001 (0.001) *** | −0.0002 (0.001) ** |

| Parameter/Parameter | ||

|---|---|---|

| Original (from Table 2) | 0.0004 (0.0002) *** | −0.0003 (0.0002) * |

| With GARCH specification | 0.0002 (0.0011) *** | −0.0002 (0.019) ** |

| Parameter/Diagnostics | Model 2 | Model 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAD f and w | Relation to the Original Model | SAD f and w | Relation to the Original Model | |

| 0.0002 (0.520) | Difference between estimated values as for and | - | - | |

| 0.0004 (0.0002) *** | - | |||

| - | - | 0.0001 (0.631) | Difference between estimated values as for and | |

| - | 0.0005 (0.000) *** | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Škrinjarić, T.; Marasović, B.; Šego, B. Does the Croatian Stock Market Have Seasonal Affective Disorder? J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14020089

Škrinjarić T, Marasović B, Šego B. Does the Croatian Stock Market Have Seasonal Affective Disorder? Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(2):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14020089

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠkrinjarić, Tihana, Branka Marasović, and Boško Šego. 2021. "Does the Croatian Stock Market Have Seasonal Affective Disorder?" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 2: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14020089

APA StyleŠkrinjarić, T., Marasović, B., & Šego, B. (2021). Does the Croatian Stock Market Have Seasonal Affective Disorder? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(2), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14020089