A Rare Case of Paired Congenital Cervical Aneurysms in a Communicating Vein: Clinical and Imaging Findings in a Pediatric Patient

Abstract

1. Introduction

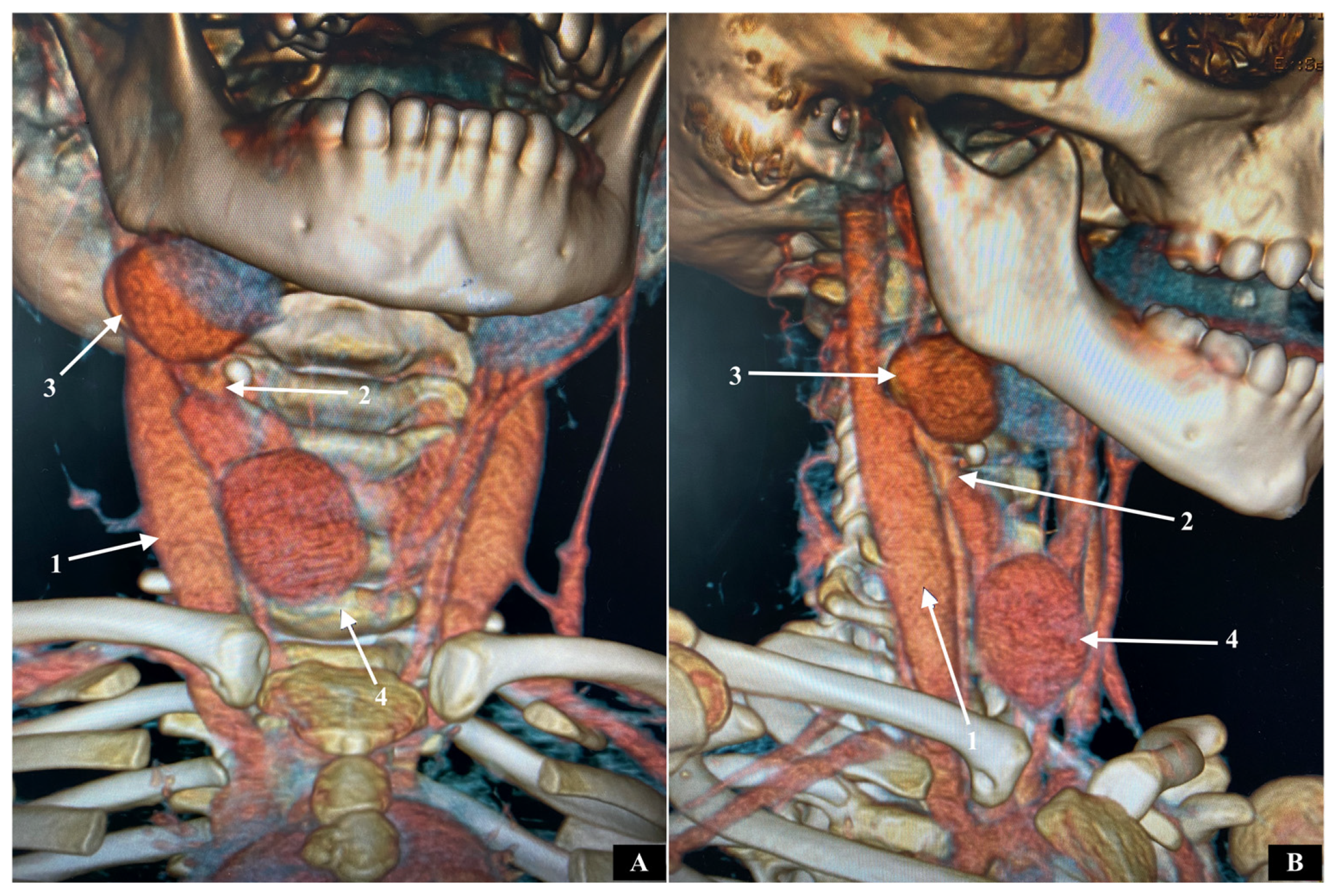

2. Case Description

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gillespie, D.L.; Villavicencio, J.L.; Gallagher, C.; Chang, A.; Hamelink, J.K.; Fiala, L.A.; O’Donnell, S.D.; Jackson, M.R.; Pikoulis, E.; Rich, N.M. Presentation and management of venous aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 1997, 26, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwa, Y.L.; Seung, M.Y.; Song, I.S.; Yu, H.; Jong, B.L. Sonographic diagnosis of a saccular aneurysm of the internal jugular vein. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2007, 35, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, S.; Dey, P.K.; Roy, A. Internal jugular vein phlebectasia presenting with hoarseness of voice. Case. Rep. Vasc. Med. 2014, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, D.; Kain, B.K.; Garg, P.K.; Tandon, A. External jugular venous aneurysm: A clinical curiosity. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2013, 4, 223–225. [Google Scholar]

- El Youbi, S.; Naouli, H.; Jiber, H.; Bouarhroum, A. External jugular vein spontaneous aneurysm: A case report. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 2022, rjac134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Bhargava, S.; Bhargava, S.K.; Gupta, R. Anterior jugular vein phlebectasia: Diagnosis by multislice CT. J. Int. Med. Sci. Acad. 2013, 26, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Zorn, W.G.W.; Zorn, T.T.; Bellen, V.B. Aneurysm of the anterior jugular vein. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1981, 22, 546–549. [Google Scholar]

- Trushin, V.; Olevson, I.; London, D.; Ayzikovich, S.; Kravchenko, Y.; Joshua, B.Z. Anterior jugulr vein aneurysm associated with neurofibromatosis Type 1. Med. Case. Rep. 2021, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.W.; Chang, J.W.; Lee, S. Unusual presentation of a cervical mass revealed as external jugular venous aneurysm. Vasc. Spec. Int. 2016, 32, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, S.W.; Balhau, R.; Coelho, L.; Pinto, I.; Correia-Sa, I.; Silva, A. Thrombosed aneurysm of the external jugular vein: A rare cause of cervical mass. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, e36–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, C.V.; Kostas, T.; Tsetis, D.; Georgakarakos, E.; Gionis, M.; Katsamouris, A.N. External jugular vein aneurysms: A source of thrombotic complications. Int. Angiol. 2010, 29, 284–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.I.; Clouse, W.D.; Bowser, A.N.; Rasmussen, T.E. Superficial venous aneurysms of the small saphenous vein. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 50, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatz, I.J.; Fine, G. Venous aneurysms. N. Engl. J. Med. 1962, 266, 1310–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessa, C.; Nicolini, P.; Perrin, M.; Farah, I.; Magne, J.L.; Guidicelli, H. Management of symptomatic and asymptomatic popliteal venous aneurysms: A retrospective analysis of 25 patients and review of the literature. J. Vasc. Surg. 2000, 32, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, M.A.; Dewan, M.; Eid, R.A. Histopathologic changes in the wall of varicose veins. Int. Angiol. 2003, 22, 188–193. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, C.; Synn, A.; Kraiss, L.; Zhang, Q.; Griffen, M.M.; Hunter, G.C. Metalloproteinase expression in venous aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 48, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekim, H.; Kutay, V.; Tuncer, M. Management of primary venous aneurysms. Saud. Med. J. 2004, 25, 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, G.; DeRowe, A.; Singhal, V. Congenital internal and external jugular venous aneurysms in a child. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2004, 24, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajadurai, A.; Aziz, A.A.; Daud, N.A.M.; Wahab, A.F.A.; Muda, A.S. Embolisation of external jugular vein aneurysm: A case report. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 24, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choundry, R.; Tuli, A.; Choundry, S. Facial vein terminating in the external jugular vein. An embryologic interpretation. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 1997, 19, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Keshelava, G.; Nasvaladze, T.; Berdzenishvili, D.; Gigilashvili, K.; Janashia, G.; Beselia, K. Surgical Treatment of the giant congenital craniofacial arteriovenous malformation: A case report. EJVES Extra 2009, 17, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.C.; Tudose, R.C.; Vrapciu, A.D.; Toader, C.; Popescu, S.A. Anatomical variations of the external jugular vein: A pictorial and critical review. Medicina 2023, 59, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keshelava, G.; Robakidze, Z.; Mikadze, I. A Rare Case of Paired Congenital Cervical Aneurysms in a Communicating Vein: Clinical and Imaging Findings in a Pediatric Patient. Pathophysiology 2025, 32, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32020025

Keshelava G, Robakidze Z, Mikadze I. A Rare Case of Paired Congenital Cervical Aneurysms in a Communicating Vein: Clinical and Imaging Findings in a Pediatric Patient. Pathophysiology. 2025; 32(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32020025

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeshelava, Grigol, Zurab Robakidze, and Igor Mikadze. 2025. "A Rare Case of Paired Congenital Cervical Aneurysms in a Communicating Vein: Clinical and Imaging Findings in a Pediatric Patient" Pathophysiology 32, no. 2: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32020025

APA StyleKeshelava, G., Robakidze, Z., & Mikadze, I. (2025). A Rare Case of Paired Congenital Cervical Aneurysms in a Communicating Vein: Clinical and Imaging Findings in a Pediatric Patient. Pathophysiology, 32(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32020025