Abstract

Women play a crucial leadership role in higher education institutions by implementing knowledge management practices; however, there is a lack of scientific studies that mainly investigate this role. Therefore, in order to fill this scientific studies gap, a purposive sampling technique focusing on women managers and a survey were employed to collect data from 201 women working in managerial positions in Lebanese and Syrian higher education institutions. PLS structural equational modeling technique and independent sample t-test were used to analyze the influence of the knowledge management cycle on sustainability in higher education institutions through women managers’ perspectives. The findings revealed a positive and significant relationship among the analyzed knowledge management processes in the study, and some insignificant differences were detected in the independent sample t-test between the Lebanese and Syrian higher education institutions. The results of this study are valuable for strategic and knowledge management practitioners concerned with women’s leadership and implementation of knowledge management practices in higher education institutions for sustainability.

1. Introduction

Women constitute fifty percent of the global population and have a crucial contribution to social and economic development [1]. Even so, there remain significant obstacles for women in leadership positions to overcome [2]. These include negative perceptions about their competencies and potential, low self-expectations, limited access to education and political representation, and undervaluation of their successes. Sustainable Development Goal 5 aims to achieve gender equality and promote women’s empowerment. Nonetheless, only a few studies have focused on the benefits of long-term women leadership in academic administration [3] in the Middle East and mainly in the Lebanese and Syrian higher education institutions (HEIs). Furthermore, compared to other scientific disciplines, the gender sustainability aspect has been under-researched and under-emphasized in knowledge management theory and practice. In this context, as the commitment to ensuring female representation in the workplace grows [4], this study seeks to address this deficiency by analyzing the perspectives of women managers through implementing knowledge management practices in HEIs.

One of the missions of HEIs is to equip individuals to meet problem solving by promoting continuous learning [5] by implementing high-level education standards and equity. All 17 sustainable development goals aim to ensure a bright and peaceful future for the entire world population, and HEIs play a crucial role in achieving this [6]. In this context, effective and efficient application of knowledge management practices in HEIs contributes to implementing sustainable development goals and leads to enhancing staff competencies, uniqueness, and leadership. These outcomes benefit the organization and the entire economy and promote a culture of lifelong learning [7,8]. This study adopts a process-oriented approach [9,10] to sustain knowledge management practices in HEIs. This perspective suggests that an organization can build a uniqueness of knowledge potential [11,12,13] through the strategic application of knowledge strategy based on integrating the knowledge management cycle, leading to sustained organizational performance and leadership. From this perspective, it is argued in this study that investigating the influence of each knowledge management process on the subsequent processes helps ensure the sustainability of the flow of knowledge in an organization and its application, as it will assist in comprehending the contribution of each process to the knowledge management cycle in HEIs. In addition, this study conducts a comparison between Lebanese and Syrian HEIs in terms of knowledge management practices for better women managers’ collaboration, transfer of best practices, and leadership.

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

The knowledge-based view [14] contends that knowledge—both tangible and intangible—should be the central element of resources and that the structure of an institution should be built to maximize the generation and use of knowledge. Individual, organizational, and national growth are dependent on knowledge [15]. Knowledge is an organization’s unique resource for building uniqueness and leadership [9]. Thus, systemizing, managing, and sustaining knowledge in an organization is critical [16] and can be adopted through a process-oriented approach [9,10]. Knowledge management is systematically managing an organization’s knowledge potential to create value in line with its strategic needs [9]. It involves approaches, procedures, sustainability measures, and knowledge processes that are essential to knowledge management [9,10,17]. In this context, the HEI’s knowledge management system serves an essential purpose and helps implement the institution’s mission. Scientists [9,18,19,20,21,22] have studied various sets of knowledge management processes [9,10,23]. Based on HEIs, women managers’ perspective, knowledge acquisition, creation, storage, sharing, and application are all areas of study to raise sustainability within an organization. The learning community should begin at the individual level by developing required individual and organizational knowledge through knowledge networks within organizations [24]. From this perspective, and starting from the personal level, this study focuses on knowing women managers’ views on the organizational level at HEIs concerning managing knowledge for five knowledge management processes: knowledge acquisition, knowledge storage, knowledge sharing, knowledge application, and knowledge creation, and the levels of these processes between HEIs located in the two different countries to enhance the network of knowledge between them.

2.1. Knowledge Acquisition

The process by which an organization attains knowledge, whether from external sources or within, is known as knowledge acquisition [9,25]. The goal is to fill a knowledge gap or gain expertise to boost the organization’s ability to create value. Therefore, managing the mechanisms by which an organization gains new and long-lasting knowledge is becoming increasingly important. It enables the organization to improve its performance as organizations can achieve sustainability by acquiring new competencies and transferring them across various organizational levels. Consequently, organizations have not only to care about how to gain knowledge but also efficiently manage the knowledge acquisition process to achieve knowledge strategy [9,26]. Al Yami et al. [27] highlighted that the acquired knowledge should be codified and preserved so that it may be included in the organization’s current knowledge base, as technological advances allow organizations to codify, digitalize, and automate processes quickly. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Knowledge acquisition positively influences knowledge storage.

2.2. Knowledge Storage

An organization’s staff’s explicit knowledge is the source of its accumulated knowledge gained from implementation, leading to learned lessons about given management methods, techniques, tools, etc. Knowledge can be shared when an organization has captured and preserved enough [9]. As a result of its ability to improve the efficiency of the knowledge management cycle, a company’s ability to grow sustainably depends on its ability to accumulate valuable knowledge. Consequently, knowledge storage is crucial to the knowledge management process [9,28]. According to Cordeiro et al. [29], the process of storing knowledge is viewed as the systematization and structuring of an organization’s knowledge stock to make it accessible and usable by its organizational members. Hence, knowledge can only be shared to be accessed when it is appropriately systemized and stored. However, scientific studies rarely handle the influence of knowledge storage on knowledge sharing. Therefore, in order to fill this study gap, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Knowledge storage positively influences knowledge sharing.

2.3. Knowledge Sharing

The knowledge sharing process refers to assisting and working with others through gained knowledge [30] to solve issues, generate new ideas, implement policies, and achieve knowledge strategy [9,31]. Organizations may make the most of their knowledge-based resources by encouraging knowledge sharing between their employees and external partners; as a result, this is an essential process that institutions should continuously pursue to maintain their long-term development and leadership [9,32]. Organizations can generate substantial value from sharing what they already know internally. Organizations initiate the knowledge sharing process for personal knowledge to be transformed to the organizational level for effective and efficient usage [33]. Therefore, organizations need to integrate knowledge sharing process into the whole knowledge management cycle, which should reflect an ongoing cycle of knowledge gathering and application [9,34]. Adeinat and Abdulfatah [35] noted that some obstacles to successfully applying knowledge strategies inside organizations might be attributable to the absence of knowledge sharing. Intezari et al. [36] emphasized that knowledge sharing should lead to knowledge application, as it permits organizations to capitalize on and employ their knowledge assets. In this context, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Knowledge sharing positively influences knowledge application.

2.4. Knowledge Application and Creation

Knowledge application, also referred to in studies as knowledge utilization [9,37], is the process that guides how effectively and efficiently knowledge is used in the form of problem solving, decisions, new idea development, or alterations to behavior. It leads to attaining objectives and the possible transformation of prevailing practices within an organization [38]. In comparison, knowledge creation refers to the collaborative and interdependent process of generating new knowledge and updating current expertise inside an organization. As a result, this process generates new knowledge [39] at the individual and corporate levels [17]. Accordingly, knowledge application enables an organization to respond swiftly to shifting macro- and micro-environment conditions by incorporating existing knowledge into activities and processes [40]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Knowledge application positively influences knowledge creation.

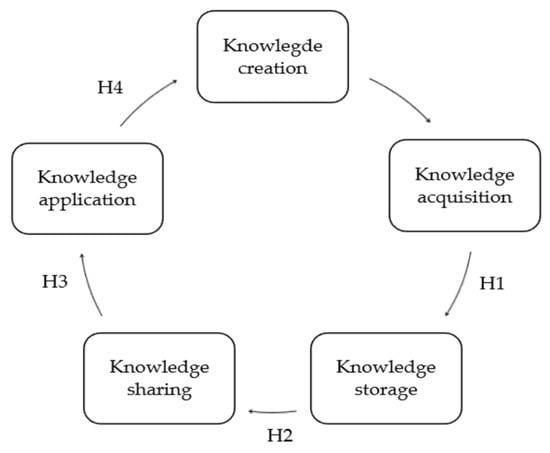

Previous studies stated that knowledge management processes were interrelated, and the improvement of one process would lead to the progress of the subsequent process. Based on this conviction, the conceptual research model for this study (Figure 1) was developed, and four research hypotheses were proposed.

Figure 1.

Conceptual research framework (created by the authors).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instrument

In order to capture women managers’ perspectives on knowledge management processes in HEIs, a survey was prepared, and a Likert scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) was employed. The survey consisted of two sections. In the first section, the purpose of the study was introduced along with demographic questions. The second section includes 24 questions related to the five knowledge management processes analyzed in the study, with five items to measure each construct, except for the knowledge application, which only had four items. The survey items were self-developed and checked with representatives of HEIs. They were experts in knowledge management to ensure that survey did not have content- or face validity-related issues. Based on their comments, a few modifications and corrections were made to the study. Then, the survey was translated into Arabic to ensure that respondents could fully capture the meaning of the questions if they were not proficient in English.

3.2. Sampling Approach and Data Collection Process

Based on scientists’ recommendations on the sample size in structural equation modeling [41,42], the sample size in the partial least squares structural equation modeling technique should be greater than 200 [43]. The potential respondents’ selection criteria were gender (female) and managerial positions in HEIs. The study was conducted from May to July 2022, and 350 possible respondents were contacted online, where 201 respondents agreed to participate in this study.

3.3. Data Analysis Programs

The data analysis was performed using Smart-PLS 3 and Version 26 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Aspects of the Participants

The age distribution of the Syrian and Lebanese female academics revealed that 52.7% of the respondents were between the ages of 20 and 35, 42.8% were between the ages of 36 and 55, and 4.5% were above the age of 56. A total of 72.1% of the participants worked in Lebanese HEIs, and 27.9% worked in Syrian HEIs.

The educational background of the respondents showed that 17.4% had a Bachelor’s degree, 56.7% had a Master’s degree, 19.4% had a Ph.D., and 6.5% indicated that they received other forms of education. A total of 36.8% had managerial positions in administrative departments, and 63.2% worked in academic departments. A total of 35.3% had one to five years of experience, 34.3% had an experience of six to ten years, and 30.4% had more than ten years of professional experience (Table 1).

Table 1.

Women managers’ demographic aspects (created by the authors).

4.2. Multicollinearity and Common Method Variance

Multicollinearity in a dataset between variables might reduce the reliability of the findings. The variance inflation factor (VIF) measures the degree of correlation between one predictor and the other predictors in a model. It is utilized for collinearity/multicollinearity diagnosis. Scientists [44] recommend the value for VIF to be less than five to avoid multicollinearity problems, as greater values indicate that it is impossible to evaluate the contribution of predictors to a model with precision. Therefore, the VIF value was calculated for all the items included in the study, and all the results revealed a value of less than 3 for the items included in the study. Furthermore, since this study only employed a survey, the common method variance (CMV) was also calculated, and the result was 42.08% (<50%).

4.3. Measurement Model

By using the smart PLS program, confirmatory factor analysis was run, and generated a factor loading matrix (Table 2). All the cross-loadings are displayed on the left side of the table, while the cleaned-up matrix is on the right. Matrix calculations show that no indicator has a cross-loading value larger than 0.6 in any dimension other than its original construct.

Table 2.

Rotated factor loading matrix (created by the authors).

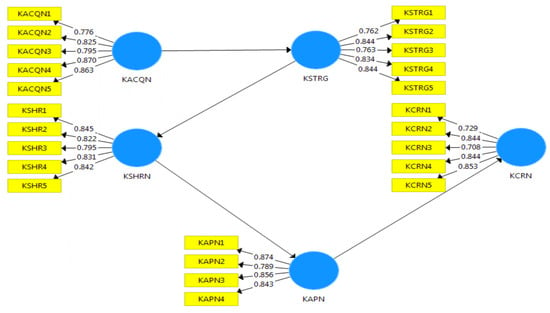

The results revealed good indicator loadings as no indicator had a value that was less than 0.703 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Indicator loadings (created by the authors).

The reliability of the constructs was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, and all calculations showed good reliability as all the values for each construct were above 0.7 [45]. Furthermore, the average variance extracted values were all greater than 0.5 for each construct, indicating convergent validity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Measurement model (created by the authors).

Discriminant Validity: for constructs to have discriminant validity, an adequate AVE analysis is required to determine whether or not discriminant validity is established. During an AVE analysis, it was checked whether the square root of every AVE value which belongs to each latent construct is significantly higher than any correlation that exists between any pair of latent constructs [46]. This method for assessing discriminant validity is also known as the Fornell and Larcker method.

In accordance with the Fornell and Larcker criterion, the discriminant validity for the constructs was confirmed as the study (Table 4) revealed that the square root of the AVE highlighted in bold and arranged diagonally is higher than inter-construct correlations [47].

Table 4.

Fornell and Larcker discriminant validity criterion-related calculations (created by the authors).

The discriminant validity of the constructs was also achieved by conducting another analysis known as the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

When the HTMT is used as a criterion, it is compared to a threshold that has been established beforehand. If the value of the HTMT is more than this threshold, it is possible to conclude that the discriminant validity of the test is lacking. A lack of discriminant validity might be inferred from HTMT values that are near 1. HTMT ratio calculations were conducted (Table 5), and all the values of the HTMT were less than the recommended threshold of 0.9 [48].

Table 5.

Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)-related calculations (created by the authors).

4.4. Structural Model Assessment and Hypotheses Testing

The structural relationships were tested at a 0.05 significance level by running a non-parametric bootstrapping technique that allows for the generation of 5000 subsamples from the original sampling size with replacement, which also yields approximate t-values for testing the significance of the structural path [49]. Therefore, a structural path is considered significant if it has a p-value that is less than 0.05. If the t-value exceeds 1.96, the path is considered significant at the 0.05 level of significance [50].

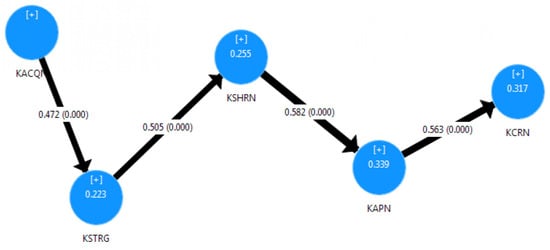

The structural model test revealed good results with a significant and positive influence among the analyzed structured relationships. The coefficient of variation (R2) related to the analyzed processes values (Figure 3) is greater than 0.2, indicating good predictive power as recommended in social science studies by scholars [51]. Furthermore, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) in this model is 0.07 (<0.08), which is within the recommended threshold. Therefore, the previously indicated measures (R2 and SRMR) suggest an acceptable model fit, as highlighted in previous research [52].

Figure 3.

Structural model (created by the authors).

The structural model test findings revealed significant positive relations (Table 6) among knowledge management processes: KACQN → KSTRG (β = 0.472, t = 7.608, p = < 0.001), KAPN → KCRN (β = 0.563, t = 9.998, p = < 0.001), KSHRN → KAPN (β = 0.582, t = 9.686, p = < 0.001), KSTRG → KSHRN (β = 0.505, t = 7.258, p = < 0.001).

Table 6.

Summary of structural model test results (created by the authors).

4.5. Independent Sample t-Test

In order to compare knowledge management processes among the Syrian and Lebanese HEIs and provide future suggestions on collaboration programs related to knowledge management, an independent sample t-test was conducted (Table 7) to test the following hypotheses at a 0.05 significance level:

Table 7.

Summary of independent sample t-test results (created by the authors).

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The knowledgeacquisition level is equal among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs;

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The knowledge acquisition level is different among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs;

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

The knowledge storage level is equal among Lebanese and Syrian HEI;

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

The knowledge storage level is different among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs;

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

The knowledge sharing level is equal among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs;

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

The knowledge sharing level is different among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs;

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

The knowledge application level is equal among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs;

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

The knowledge application level is different among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs;

Hypothesis 13 (H3).

The knowledge creation level is equal among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs;

Hypothesis 14 (H14).

The knowledge creation level is different among Lebanese and Syrian HEIs.

The independent sample t-test revealed a significant difference in knowledge acquisition between Syrian and Lebanese HEIs, t(199) = 2.578, p = 0.011, 95% C.I. (0.0550–0.4132). The Lebanese HEIs have, on average, a higher knowledge acquisition level in their organizations (M = 3.884, SD = 0.5665) as compared to Syrian HEIs (M = 3.650, SD = 0.6045). Therefore, H5 is rejected. A significant difference in knowledge storage is noticed: t(199) = 2.617, p = 0.010, 95% C.I. (0.0564–0.4011). The Lebanese HEIs have, on average, a higher knowledge storage level in their organizations (M = 3.836, SD = 0.5450) as compared to Syrian HEIs (M = 3.607, SD = 0.5821). Therefore, H7 is rejected. Furthermore, there is a significant difference in knowledge sharing: t(81.158) = 2.006, p = 0.048, 95% C.I. (0.0018–0.4252). The Lebanese HEIs have, on average, a higher knowledge sharing level in their organizations (M = 3.803, SD = 0.5508) as compared to Syrian HEIs (M = 3.589, SD = 0.7190). Therefore, H9 is rejected. However, the independent sample t-test reported an insignificant difference in knowledge application between Syrian and Lebanese HEIs: t(199) = 0.469, p = 0.640, 95% C.I. (−0.1365–0.2216). There is no significant difference between the Lebanese HEIs in knowledge application level in their organizations (M = 3.789, SD = 0.5446) as compared to Syrian HEIs (M = 3.746, SD = 0.6545). Therefore, H11 is accepted. The independent sample t-test also reported an insignificant difference in knowledge creation: t(199) = 1.350, p = 0.179, 95% C.I. (−0.0579–0.3091). There is no significant difference between the Lebanese HEIs’ knowledge creation level in their organizations (M = 3.883, SD = 0.5738) compared to Syrian universities (M = 3.757, SD = 0.6356). Therefore, H13 is accepted.

5. Discussion of the Results and Conclusions

The importance of this study is mainly related to its emphasis on women managers in Lebanese and Syrian HEIs, as the glass ceiling pertaining to a career still persists, and women’s representation in managerial positions remains low [53]. This study assessed knowledge management processes in HEIs through women managers’ perspective as knowledge-oriented leaders [13] who could prioritize knowledge by communicating a compelling vision and offering guidance to implement knowledge strategy in HEIs for sustainable leadership [54].

The sample size in this study involved 201 women managers, and it was satisfactory to use the partial least squares structural equation modeling technique. The findings indicated that the measurement model meets all the requirements. The reliability and validity of the constructs were achieved. Furthermore, the structural model test revealed a high positive significance among the analyzed knowledge management processes. The highest influence was for knowledge sharing on knowledge application: KSHRN → KAPN (β = 0.582, t = 9.686, p = < 0.001). Therefore, HEIs should emphasize knowledge sharing in their institution to improve knowledge application and sustainability. The second-highest influence was for knowledge application on knowledge creation: KAPN → KCRN (β = 0.563, t = 9.998, p = < 0.001). Thus, HEIs should encourage staff to apply existing organizational knowledge to solve problems or find ways to facilitate the knowledge creation process to find new solutions and innovative knowledge potential for new educational programs. The influence of knowledge storage on knowledge sharing, KSTRG → KSHRN (β = 0.505, t = 7.258, p = < 0.001), also showed a high significance. Therefore, storing knowledge efficiently in HEI databases and making it accessible should be highly prioritized. Concerning the influence of knowledge acquisition on knowledge storage, the results were also reinforcing: KACQN → KSTRG (β = 0.472, t = 7.608, p = < 0.001), which indicates that HEIs are encouraged to foster information technologies that enhance their knowledge storage capabilities, enabling the acquisition of knowledge from various inner and outer sources to increase knowledge potential.

The independent sample t-tests revealed a significant difference in knowledge acquisition, sharing, and storage between the Lebanese and Syrian HEIs. The Lebanese HEIs have, on average higher levels in these processes, and it would be beneficial for the Syrian HEIs to find collaborative ways to gain best practices from Lebanese HEIs.

This study’s motive was mainly related to empowering women by basing the research results on their insights about knowledge management in HEIs. In addition, improving knowledge processes could reduce costs incurred due to a knowledge gap that can be filled through knowledge acquisition and storage. When HEI staff learn how to transfer their acquired knowledge into the organizational repository for the appliance knowledge according to the need, it will facilitate the knowledge creation process and HEI sustainability.

This study contributes to the knowledge management field by providing a knowledge management framework that integrates the influence of each knowledge management process on the proceeding process in the knowledge management cycle within the HEI context through women managers’ perspectives. Lebanese and Syrian HEIs are encouraged to consider this study’s results as guidelines on implementing the whole knowledge management cycle as a tool for sustainable development and leadership.

This study has two main limitations. The first limitation is related to the countries of the study, since it was conducted in Lebanon and Syria, and the results of this research are applicable to Lebanese and Syrian HEIs. The second limitation is that this study handled knowledge management processes without integrating individual and organizational factors influencing processes. Hence, future research is required with a wider geographical region to improve the generalizability of the findings, and the factors that influence these processes should be integrated to have an enhanced knowledge management framework in HEIs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R. and I.M.; Data curation, I.M.; Formal analysis, I.M.; Funding acquisition, J.R.; Investigation, J.R. and I.M.; Methodology, J.R. and I.M.; Project administration, J.R.; Resources, J.R. and I.M.; Software, I.M.; Supervision, J.R.; Validation, J.R. and I.M.; Visualization, I.M.; Writing—original draft, J.R. and I.M.; Writing—review and editing, J.R. and I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the research purpose of analyzing women managers’ perspectives on knowledge management practices for sustainable development in higher education institutions.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Raman, R.; Subramaniam, N.; Nair, V.K.; Shivdas, A.; Achuthan, K.; Nedungadi, P. Women Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development: Bibliometric Analysis and Emerging Research Trends. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, E.; Riera, M.; Rodríguez, R. The Importance of Sustainable Leadership amongst Female Managers in the Spanish Logistics Industry: A Cultural, Ethical and Legal Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merma-Molina, G.; Urrea-Solano, M.; Baena-Morales, S.; Gavilán-Martín, D. The Satisfactions, Contributions, and Opportunities of Women Academics in the Framework of Sustainable Leadership: A Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Fernández, M.; Fernández-Torres, Y. Does Gender Diversity Influence Business Efficiency? An Analysis from the Social Perspective of CSR. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnucci, L.; Spigarelli, F. The Third Mission of the University: A Systematic Literature Review on Potentials and Constraints. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre, E.M.; Perez-Encinas, A.; Gomez-Mediavilla, G. Fostering Sustainability through Mobility Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalauskiene, A.; Atkociuniene, Z. Knowledge Management Impact on Sustainable Development. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2019, 15, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Yu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Harms, R.; Fang, G. Knowledge Growth in University-Industry Innovation Networks—Results from a Simulation Study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 151, 119746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliūnienė, J. Organizacijos Žinių Potencialo Vertinimo Aktualijos [Actualities of Evaluating the Knowledge Potential of the Organization]; Monograph; Technika: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliūnienė, J.; Davidavičienė, V.; Jakubavičius, A. Knowledge Management Process Model. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2018, 5, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliūnienė, J.; Davidavičienė, V.; Petrusevičius, R. Factors influencing knowledge retention process: Case of Lithuanian armed forces. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2018, 24, 1104–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliūnienė, J.; Szarucki, M. An integrated approach to assessing an organization’s knowledge potential. Eng. Econ. 2019, 30, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliūnienė, J.; Kordab, M. Impact of knowledge oriented leadership on knowledge management processes in the Middle Eastern audit and consulting companies. Bus. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-M.; Nham, T.P.; Froese, F.J.; Malik, A. Motivation and Knowledge Sharing: A Meta-Analysis of Main and Moderating Effects. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 998–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Comite, U.; Yucel, A.G.; Liu, X.; Khan, M.A.; Husain, S.; Sial, M.S.; Popp, J.; Oláh, J. Unleashing the Importance of TQM and Knowledge Management for Organizational Sustainability in the Age of Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Knowledge Management in Startups: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajpour, M.; Hosseini, E.; Mohammadi, M.; Bahman-Zangi, B. The Effect of Knowledge Management on the Sustainability of Technology-Driven Businesses in Emerging Markets: The Mediating Role of Social Media. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Al-Ahbabi, S.; Sreejith, S. Knowledge Management Processes and Performance: The Impact of Ownership of Public Sector Organizations. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2019, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.; Hodgkinson, I. Knowledge Management Activities and Strategic Planning Capability Development. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2021, 33, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annansingh, F.; Howell, K.E.; Liu, S.; Baptista Nunes, M. Academics’ Perception of Knowledge Sharing in Higher Education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gharaibeh, R.S.; Ali, M.Z. Knowledge Sharing Framework: A Game-Theoretic Approach. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 332–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mete, M.H.; Belgin, O. Impact of Knowledge Management Performance on the Efficiency of R&D Active Firms: Evidence from Turkey. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 830–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi Boroujerdi, S.; Hasani, K.; Delshab, V. Investigating the Influence of Knowledge Management on Organizational Innovation in Higher Educational Institutions. Kybernetes 2019, 49, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Do, A.D.; Nguyen, Q.V.; Ta, V.L.; Dao, T.T.B.; Ha, D.L.; Hoang, X.T. Research on Knowledge Management Models at Universities Using Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP). Sustainability 2021, 13, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, S.; Alegre, J. Information Technology Competency, Knowledge Processes and Firm Performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2012, 112, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugalde Vásquez, A.F.; Naranjo-Gil, D. Management Accounting Systems, Top Management Teams, and Sustainable Knowledge Acquisition: Effects on Performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yami, M.; Ajmal, M.M.; Balasubramanian, S. Does Size Matter? The Effects of Public Sector Organizational Size’ on Knowledge Management Processes and Operational Efficiency. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Shang, Y.; Wang, N.; Ma, Z. The Mediating Effect of Decision Quality on Knowledge Management and Firm Performance for Chinese Entrepreneurs: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, M.d.M.; Oliveira, M.; Sanchez-Segura, M.-I. The Influence of the Knowledge Management Processes on Results in Basic Education Schools. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShamsi, O.; Ajmal, M. Critical Factors for Knowledge Sharing in Technology-Intensive Organizations: Evidence from UAE Service Sector. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 384–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.G.; Lee, K.C. Emotional Factors Affecting Knowledge Sharing Intentions in the Context of Competitive Knowledge Network. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pascual, L.; Galende, J.; Curado, C. Human Resource Management Contributions to Knowledge Sharing for a Sustainability-Oriented Performance: A Mixed Methods Approach. Sustainability 2019, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-B.; Lin, C.-H.; Chung, K.-C.; Tsai, F.-S.; Wu, R.-T. Knowledge Sharing and Co-Opetition: Turning Absorptive Capacity into Effectiveness in Consumer Electronics Industries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afandy, D.; Gunawan, A.; Stoffers, J.; Kornarius, Y.P.; Caroline, A. Improving Knowledge-Sharing Intentions: A Study in Indonesian Service Industries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeinat, I.M.; Abdulfatah, F.H. Organizational Culture and Knowledge Management Processes: Case Study in a Public University. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2019, 49, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intezari, A.; Pauleen, D.J.; Taskin, N. Towards a Foundational KM Theory: A Culture-Based Perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 1516–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahibzada, U.F.; Jianfeng, C.; Latif, K.F.; Sahibzada, H.F. Fueling Knowledge Management Processes in Chinese Higher Education Institutes (HEIs): The Neglected Mediating Role of Knowledge Worker Satisfaction. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 33, 1395–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.C.K.; Lee, J.C.K. Knowledge Management Process for Creating School Intellectual Capital. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2016, 25, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C. Effect of Knowledge Management and Co-Evolvement on Green Operations: The Role of Corporate Environmental Strategy. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.T.; Lo, M.C.; Suaidi, M.K.; Mohamad, A.A.; Razak, Z.B. Knowledge Management Process, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Performance in SMEs: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Sampling Methods in Research Methodology; How to Choose a Sampling Technique for Research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2016, 5, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ahbabi, S.A.; Singh, S.K.; Balasubramanian, S.; Gaur, S.S. Employee Perception of Impact of Knowledge Management Processes on Public Sector Performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, I.; Raudeliūnienė, J. The Role of Knowledge Acquisition in Enhancing Knowledge Management Processes in Higher Education Institutions. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Contemporary Issues in Business, Management and Economics Engineering 2021, Vilnius, Lithuania, 13–14 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwande, M.O.; Dikko, H.G.; Samson, A. Variance Inflation Factor: As a Condition for the Inclusion of Suppressor Variable(s) in Regression Analysis. Open J. Stat. 2015, 05, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyoubi, B.; Hoque, R.; Alharbi, I.; Alyoubi, A.; Almazmomi, N. Impact of Knowledge Management on Employee Work Performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Int. Technol. Manag. Rev. 2018, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zait, A.; Bertea, P.E. Methods for Testing Discriminant Validity. Manag. Mark. J. 2011, 9, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Mohmad Sidek, M.H. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker Criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, A.S.M.; Peng, F.S.; Razak, F.Z.A.; Mustafa, W.A. Discriminant Validity Assessment of Religious Teacher Acceptance: The Use of HTMT Criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1529, 042045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.d.C.G.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Medina-Merodio, J.-A.; Robina-Ramírez, R.; Fernandez-Sanz, L. Relationships among Relational Coordination Dimensions: Impact on the Quality of Education Online with a Structural Equations Model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karani, A.; Thanki, H.; Achuthan, S. Impact of University Website Usability on Satisfaction: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Manag. Labour Stud. 2021, 46, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilani, M.M.A.K.; Fan, L.; Islam, M.T.; Uddin, A. The Influence of Knowledge Sharing on Sustainable Performance: A Moderated Mediation Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, M.A.; Anyigba, H.; Ofori, K.S.; Ampong, G.O.A.; Addae, J.A. Factors Influencing Innovation Performance in Higher Education Institutions. Learn. Organ. 2020, 27, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejase, H.; Haddad, Z.; Hamdar, B.; Massoud, R.; Farha, G. Female Leadership: An Exploratory Research from Lebanon. Am. J. Sci. Res. 2013, 86, 28–52. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, K.F.; Afzal, O.; Saqib, A.; Sahibzada, U.F.; Alam, W. Direct and Configurational Paths of Knowledge-Oriented Leadership, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Knowledge Management Processes to Project Success. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020, 22, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).