Abstract

With the advancement of consumers’ awareness of environmental protection, the green supply chain, a modern management model considering environmental impact and resource efficiency, is increasingly valued by managers and consumers and has become an important determinant of crowdfunding success. Different from existing research on crowdfunding with symmetric thinking, this paper employs text mining and the QCA method to identify various configurations of crowdfunding success. Based on the data of the leading Chinese crowdfunding platform, JD Crowdfunding, this paper studies multiple configurations of the green supply chain, delivery time and funding goals of crowdfunding projects in the technology category. The results show that a crowdfunding project that adopts a green supply chain can succeed with a higher funding goal and longer delivery time, and a project without a green supply chain but with a lower funding goal is also a successful configuration. In addition, this study also explores the successful configuration paths of hedonic products and functional products in crowdfunding projects, respectively, and it finds that investors of hedonic products pay more attention to green supply chain management. These findings support complexity theory, deepen the understanding of the success of crowdfunding projects, and provide important management suggestions for fundraisers and crowdfunding platforms.

1. Introduction

The rapid industrialization process is not only harmful to the environment but also harmful to human health [1]. At present, globally, a safe and sustainable environment and economy have become the commitment of countries and enterprises. With the improvement of public awareness of environment, sustainable development and social responsibility, consumers favor green products [2]. Richard Thaler, a 72-year-old American economist who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2017, believes that completely rational economic people do not exist, and people’s various economic behaviors will inevitably be affected by various “irrationality”. Irrational consumption refers to phenomenon such as bounded rationality, social preferences, lack of self-control, and other factors. Studies have shown that consumers will consider social benefits, ecological values, etc. when consuming, and there is green consumption behavior in current consumption behavior [3,4]. Some pro-social consumer behaviors may lead a consumer to buy products affiliated with “cause-related marketing”. Pro-social framing affects the success of crowdfunding projects [5]. Therefore, with the continuous improvement of people’s living standards and environmental awareness, the concept of green consumption has been accepted by the public, and consumers support green-conscious enterprises and purchase green products. Green products pay more attention to environmental consumption and resource utilization than traditional products. Enterprises implement green supply chain management to the whole product life cycle and timely adjust the standards of the green products [6].

With the emergence of environmental problems such as extreme weather and resource shortages, the green supply chain based on green manufacturing theory and supply chain management technology has become a modern management model that comprehensively considers the environmental impact and resource utilization efficiency and aims to improve the optimal utilization efficiency [7]. It involves suppliers, manufacturers, sellers and logistics providers. Its purpose is to minimize the negative impact on the environment, improve resource efficiency and promote sustainable development in the manufacturing, transportation and postprocessing of the entire product [8]. With the globalization of the supply chain, international companies such as GM and Walmart have announced the implementation of green supply chain management strategies and are transforming into green suppliers [9]. Their practice shows that green management of the whole process of design, raw material supply, product manufacturing, sales and waste recycling can enhance product competitiveness. Many studies have shown that the green supply chain has improved the profitability of enterprises and brought many benefits, such as saving energy, saving costs, improving the competitiveness of enterprises, and enhancing the capacity for sustainable development [10,11,12,13]. Some enterprises fulfill their environmental protection responsibilities through the green supply chain while improving the efficiency of resource utilization and promoting the sustainable development of enterprises [14]. Based on institutional theory, Zhu [15] esteems that implementing a green supply chain can affect economic performance by improving environmental and operational performance.

However, when implementing green supply chain management to promote green products, the price is often higher than that of other products due to the green properties of its products. The lack of funds is often an obstacle to implementing green supply chain management, and crowdfunding provides a new idea for enterprises to raise funds [6].

In recent years, crowdfunding, inspired by microfinance [16] and crowdsourcing [17], has become a new way for start-ups to obtain funds. The source of funds is no longer limited to venture capital and other companies but can be the public interested in crowdfunding projects [18]. Compared with traditional financing channels, the Internet-based crowdfunding model has received more attention and developed rapidly [19]. In 2019, the total transaction volume of the crowdfunding business in the world is USD 6923.6 million, and the total number of crowdfunding business is 872,400; it is estimated that by 2023, the total transaction volume of the crowdfunding business will reach USD 11,985 million, and the total number is expected to reach 1,206,390, with the average financing amount of projects in crowdfunding activities reaching USD 780 [20]. At present, there are various crowdfunding models such as donation-based, lending-based, equity-based and reward-based; the most popular one is reward crowdfunding, in which sponsors receive non-monetary returns. This study focuses on reward-based crowdfunding [19].

Since the failure rate of crowdfunding projects has reached approximately 60% [21], the determinants of project success are a hot issue in the study of crowdfunding projects, which are also the focus of this article. Some studies have identified several factors that have an impact on crowdfunding outcomes. Miglo [22] believed that the quality of projects affects the funding outcome; i.e., crowdfunding projects with high quality are more likely to attract investors and obtain financing. Hobbs [23] found that a detailed text description is a way to establish trust between investors and fundraisers, so detailed information disclosure has a certain impact on the funding outcome. Mollick [18] believed that project goals, delivery time and the number of Facebook friends of fundraisers impact funding outcomes. In addition, the amount of investor support impacts funding outcomes [24]. Friends and families play an important role in early crowdfunding investments [25], and the number of early investors and early capital impacts the success of crowdfunding projects [26]. Yuan [27] used the DC-LDA topic model to extract topics from the project description so that the fundraisers could promote the success of projects by embedding the most influential topic features in project descriptions. To sum up, previous studies on crowdsourcing mainly focused on project characteristics and investment behavior. However, with the improvement of environmental awareness, some consumers have begun to care about whether crowdfunding projects contain green factors. Although studies have shown that environmental or sustainable development orientation has an impact on funding outcomes [28], few people have explored how investors’ investment behaviors will react when green supply chains are incorporated into crowdfunding projects.

At present, some scholars have begun to explore the influencing factors of the success of cleantech crowdfunding. Cumming provided insights on the crowdfunding of new alternative energy technologies by enabling inferences from large pools of small investors [29]. Cumming identifies cleantech as encompassing four main sectors—energy, transportation, water, and minerals—and explores the factors that influence the success of cleantech crowdfunding. Ppo explores the combinational effect of the six success factors identified in the general crowdfunding literature for cleantech projects published on the Kickstarter platform. The research variables include target amount, locality of backers, compelling emotional appeal of the campaign/narrative, communication with backers–campaign updates, duration of crowdfunding campaign and entrepreneur’s gender [30]. To sum up, previous scholars mainly explored the impact of a single characteristic variable on the success of clean crowdsourcing. However, few scholars have explored the greening of crowdsourcing project products based on the whole life cycle of crowdsourcing project products. To make up for this deficiency, this study evaluates the greening of every link of the product life cycle by building a vocabulary related to the green supply chain.

To sum up, researchers have shown that with the improvement of people’s environmental protection awareness, consumers have accepted green products and enterprises have begun to improve environmental performance through the implementation of green supply chain management [3,31]. In addition, crowdfunding has become a way for enterprises to raise funds for green production. However, previous studies are mainly based on the characteristics of crowdfunding projects [21,22,23,24] and have not explored the impact of environmental factors on the success of crowdfunding projects. Although some scholars have begun to explore the success factors of clean technology projects [29,30], they have neglected to examine the impact of the whole life cycle of crowdfunding project products on the results of crowdfunding projects. Moreover, few studies have explained how to configure the elements of the green supply chain and the characteristics of crowdfunding projects to achieve success of crowdfunding projects. To remedy this gap in research, we applied the qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) method, which combines qualitative and quantitative analysis using set theory and complexity theory as well as Boolean algebra.

Previous studies on the success factors of crowdfunding projects are mainly multiple regression analysis and structural equations, but regression analysis assumes that variables (conditions) play an independent role, focusing on the study of the unique “net effect” of a single variable. The problem is that when independent variables are correlated, the unique effects of a single variable may be masked by the correlated variable. QCA analysis no longer assumes that causal conditions are independent but focuses on “configuration effect” analysis from a holistic perspective to study the causal relationship between condition configuration and results. It does not study the influence of a single condition on the outcome but combines it with other conditions to study the effect of the condition configuration on the result [32]. Different combinations of antecedent conditions lead to the same results, which may come from the existence and absence of a certain antecedent condition. QCA provides a method for solving complex condition configurations [33].

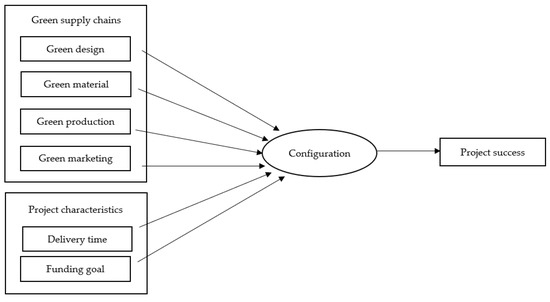

This paper explores the essential green supply chain factors (green design, green materials, green production, green marketing) and project characteristics (delivery time and funding goal) that influence the project’s success. For entrepreneurs who consider the green supply chain, this will help them to make better decisions. Ragin [34] believes that a configuration model composed of factors with high consistency and coverage is sufficient to predict the success of crowdfunding projects. These models illustrate that a single conditional variable cannot produce a specific result. The result is affected by multiple conditional configurations [32]. Therefore, we try to explore the impact of the combinations of multiple variables on achieving the success of the crowdfunding project.

The paper is expanded as follows. Section 2 is a literature review of crowdfunding and the green supply chain. Section 3 introduces theoretical assumptions. Section 4 presents data collection and interpretation. The results are presented in Section 5, followed by a discussion and summary in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

This study aims to study the impact of the characteristics of crowdfunding projects and the involvement of the green supply chain on the success of crowdfunding projects. Therefore, this section reviews the literature on crowdfunding and green supply chains.

2.1. Crowdfunding

In the reward-based crowdfunding project, investors obtain corresponding rewards after the successful funding of crowdfunding projects. The project’s reward has a certain impact on investor decision-making behavior [35,36]. Fundraisers attract investors to invest by setting different types of rewards [37]. Based on signal theory, Xiao [38] found that the length of the video and description text significantly affect the actual financing outcome of crowdfunding. By analyzing 1507 reward-based crowdfunding projects, Lagazio [39] concluded that the accuracy of project descriptions impacts the crowdfunding campaign’s success. Xu [40] found that updating project descriptions affected crowdfunding projects’ success. Zhang [19] uses fuzzy set qualitative analysis to determine that the funding goal, update number, support number and minimum pledge have an important impact on the funding outcome. In addition, the success of crowdfunding projects is affected by the popularity of project fundraisers, and projects initiated by more prominent people are easier to succeed [25].

Previous studies on the influencing factors of crowdfunding projects mainly focus on project characteristics and fundraiser dynamics. Some studies also explore funding outcomes from investors’ investment behavior. Zvilichovsky’s study showed that if project sponsors had previously supported other projects [41], the behavior would have a positive impact on funding outcomes. Investors’ investment behavior shows a herding effect, which is affected by existing investors’ project progress and investment behavior [42]. In the project implementation stage, timely communication between sponsors and investors can effectively alleviate the information asymmetry between the two sides, increase investors’ perception of project prospects, and affect their investment behavior [38].

In summary, significant progress has been made in research on the determinants of crowdfunding success. The research on crowdfunding mainly focuses on two aspects. One is to explore the impact of project characteristics that directly affect crowdfunding outcomes [37,38,39,40], and the other is to analyze crowdfunding outcomes from the perspective of investors’ behavior [41,42]. However, with the deterioration of the environment and the awakening of people’s environmental awareness, people have begun to pay attention to whether fundraisers carry out green management in the production process. Therefore, the research on the determinants of crowdfunding success is no longer limited to project characteristics and investors’ investment behavior, and the green management of projects also impacts crowdfunding outcomes.

2.2. Green Supply Chain

The Manufacturing Research Council of Michigan State University proposed the green supply chain in 1996, which considers environmental factors from product design to raw materials to product production, and ultimately to product warehousing, logistics and distribution. Beamon proposed that the recycling of products should be fully considered in the whole supply chain of products, which enriched the content of the green supply chain [43]. After the 21st century, with the in-depth exploration of green manufacturing, some scholars have proposed new ideas about the connotation of the green supply chain. Sarkis explored integrating environmental decisions with supply chain decisions [44]. Stephan and Robert started from the two aspects of enterprises and suppliers. Enterprises can evaluate and select suppliers through customer information feedback and cooperate with suppliers to jointly develop environmental protection programs [45]. Herrmann proposed a conceptual framework to identify a green supply chain management model and a set of green dimensions, categories, and practices [46].

At present, the green supply chain has attracted the attention of academia. Some organizational theories provide a theoretical basis for the study of the green supply chain, such as complexity theory [47], ecological modernization [44], and institutional theory [48]. Zhu [15] used a sample of 396 Chinese manufacturers and assessed the impact of three institutional pressures, namely, normative pressure, coercive pressure, and mimetic pressures, on implementing a green supply chain by enterprises based on institutional theory. The empirical results show that implementing a green supply chain can affect economic performance by improving environmental and operational performance. Li revealed the relationship between GSCM pressure, practice, and performance under the moderating effect of quick response (QR) technology [13]. Ball and Craig believed that the green supply chain could be achieved according to different practices and used robust ranking technology to evaluate green supply chain practice and performance [47]. They employed neutrosophic set theory to handle data, knowledge, information and imprecision. The empirical results show that ‘reverse logistics’, ‘supplier environmental collaboration’ and ‘carbon management’ are significant in GSCM practice.

Through the literature review, we can see that the current research on green supply chain mainly focuses on two aspects; one is to explore the connotation of the green supply chain, and the other is to explore the practice and performance of the green supply chain. Studies have shown that green management has a certain impact on the performance of enterprises, but few studies have demonstrated the effects of a green supply chain on crowdfunding results, and the existing studies have paid little attention to the impact of the comprehensive impact of various elements of the green supply chain on performance. Previous studies have used traditional multiple regression models to explore the impact of variables on crowdfunding results, which assume that variables are independent, so when there is a correlation between variables, the effect of a single variable may be covered by the correlation effect. Moreover, regression analysis has difficulty explaining the complex causal relationship between the configuration of variables and the results. Therefore, we use the QCA method to better express the causal relationship between conditional configuration and crowdfunding outcome.

2.3. QCA

Compared with the traditional symmetry method, QCA provides more insights into the effect of interaction among variables on the results. In recent years, QCA has received increasing attention in management research. QCA has mainly been used in organizational management in the past few years. For example, in terms of strategic types, Fiss [49] uses QCA to determine how to configure enterprise strategies to achieve higher delivery performance reasonably. At present, QCA is also used in other areas, such as combining QCA with process-tracing techniques, revealing the successful path of monitoring systems [50]. QCA was combined with a structural equation model to study Bitcoin [51]. QCA was used to analyze unstructured data, calculate configurational models for different years, and illustrate the evolution of configurations [52]. QCA has been applied in the field of crowdfunding research. For example, Xu [40] used QCA to study the satisfaction of crowdfunding, and Tuo [53] used the data of crowdfunding platforms to identify different configurational paths to deliver performance through QCA.

At present, there are few studies linking the green supply chain with crowdfunding project characteristics and analyzing how to reasonably configure conditions to achieve crowdfunding success. Therefore, this study used asymmetric analysis to explore the impact of the green supply chain (green design, green materials, green production, green marketing) and basic characteristics of crowdfunding projects (delivery time, funding goal) on the success of crowdfunding and obtained several configuration paths that make crowdfunding projects successful. In this study, QCA combines quantitative and qualitative data to study the influence of the interaction between various conditions on the funding outcome.

3. Configuration Model

This section proposes theoretical hypotheses based on the crowdfunding and green supply chain literature.

3.1. Green Supply Chain

With the widely recognized idea of the ecological environment and sustainable development, the green supply chain puts higher demands on resources and provides more environmental benefits than the traditional supply chain. Scholars have researched the concept of green supply chains. Jiang [8] argued that environmental protection consciousness should be run through the green supply chain and be referred to as several specific components of the green supply chain: green design, green materials, green manufacturing, green packaging, green consumption and green recycling. In 2007, Srivastava proposed that green supply chain management has the least negative effect on the environment and the highest resource efficiency in product design, procurement, manufacturing, distribution and terminal management of the product life cycle. Sezen and Çankaya believed that green supply chain management is an important part of environmental and supply chain strategy, which considers all activities in the supply chain, from raw material procurement, inbound logistics, production, outbound logistics, marketing, and after-sales to appropriate product disposal throughout the supply chain process to achieve the purpose of greening the supply chain [54]. Vargas divided green supply chain management practices into two dimensions: corporate green practices and social practices. Green practices include green procurement, design, manufacturing, logistics, customer cooperation and recycling, and social practices include employee safety management, product safety, community responsibility, and senior and middle management support [55]. Foo measures green supply chain management practices from seven dimensions: internal environmental management, customer cooperation, investment recovery, green design, supplier selection, supplier cooperation and supplier evaluation [56]. There are various ways of classifying green supply chain management practices in the academic community. Comprehensively considering existing research at home and abroad and combining with the description of crowdfunding projects, green supply chain management practices are divided into green design, green materials, green production and green marketing.

3.1.1. Green Design

When design brings convenience to humans, it also causes environmental damage and resource consumption. In this context, people begin to consider green design [57]. In the whole product cycle, green design takes the environmental attributes of the entire product as the design goal, which not only meets the environmental requirements but also ensures the functions, service life and quality of the product. There are recognized principles of green design, which are “3R”: reduce, recycle, reuse [58]. Green design is an important prerequisite to achieving green products. Green design can promote the sustainable development of enterprises and attract more consumers [59]. Thus, we propose green design as part of the antecedent conditions for project success. We put forward the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Green design would serve as an antecedent condition and can be combined with other causal conditions to influence the success of crowdfunding projects.

3.1.2. Green Material

Green material is the raw material procurement stage in the green supply chain, which is an important component of green design and manufacturing [60]. Green material has the least environmental pollution and is beneficial to human health in the process of raw material acquisition, product production, use, recycling and waste treatment [61]. All countries are paying increasing attention to environmental protection and taking action to forbid toxic materials accordingly. Therefore, it is necessary for entrepreneurs to integrate environmental ideas into the selection of materials in advance. As an important part of the green supply chain, green materials reflect whether the product has green characteristics [62]. Moon [63] found that consumers pay more attention to whether a product has green characteristics and are willing to spend more than ordinary products. Green material affects the choice of consumers. Thus, we think green material would be part of the antecedent conditions influencing the success of crowdfunding projects. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Green material would serve as an antecedent condition and can be combined with other causal conditions to influence the success of crowdfunding projects.

3.1.3. Green Production

With the increasing shortage of global resources, it has become increasingly important for enterprises to save energy and reduce emissions through green production. Green production has also been called “clean production”. It was first proposed by the UNEP in 1989, which means saving energy and reducing waste discharge through strict management and advanced technology throughout the manufacturing process of products to realize minimum environmental pollution and maximum efficiency. In 1994, some management philosophy supporters thought green manufacturing was beneficial to the environment and strengthened the enterprise’s competitiveness [64]. Through a random sample survey, Mohr [65] found that consumers preferred enterprises with green production and preferred to purchase environmentally friendly products. Previous studies have shown that green production affects consumers’ choice of products [66]. Therefore, green production serves as an antecedent condition to achieve the outcome of the project’s success. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Green production would serve as an antecedent condition and can be combined with other causal conditions to influence the success of crowdfunding projects.

3.1.4. Green Marketing

In his book Green Marketing—Turning Crisis into Business Opportunities, Ken Peattie of the University of Wales pointed out that green marketing is a marketing approach that focuses on sustainable development and environmental protection while meeting the common interests of producers and consumers. The development of green marketing has gone through three stages: “ecological” green marketing, “environmental” green marketing and “sustainable” green marketing [67]. Scholars have studied the importance of green marketing. Green marketing enhanced corporate social responsibility, promoted sustainable corporate development and benefited enterprises to promote green cultures, strengthening competitive advantages and improving economic profits [68]. Astuti [69] investigated consumers randomly and concluded that green marketing significantly positively impacted purchasing decisions. Therefore, in this study, green marketing is considered an antecedent condition for the success of crowdfunding projects. Thus, the hypothesis is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Green marketing would serve as an antecedent condition and can be combined with other causal conditions to influence the success of crowdfunding projects.

3.2. Project Characteristics

Previous studies have shown that funding goals and delivery time are important factors in the success of crowdfunding projects. Kuppuswamy [21] put forward a unique view. When the financing goal is close to and does not exceed people’s expectations, people are easier to fund the project, meaning that the project is more likely to succeed. If the project succeeds, the sponsor promises a date as the delivery date of the reward and completes the award within the specified date. If this delivery date is close to or does not exceed people’s expectations, people are easier to fund this project, and this project is easier to succeed [69]. In contrast, long delivery intervals allow fundraisers more time and opportunities to polish their products and optimize their campaigns [70]. Based on the literature on the success of crowdfunding, this study considers the impact of delivery time and funding goals on the success of crowdfunding projects.

3.2.1. Delivery Time

For consumers, waiting time for products and services has a certain impact on their purchasing behavior. In addition, delivery time is a substantive signal, and it reflects the planned interval from the end of the campaign to the estimated reward delivery. This signal commits a fundraiser to make every effort to complete the project and deliver the rewards on time [70]. Project fundraisers with crowdfunding experience formulate a more reasonable delivery time [71]. The length of delivery time reflects the preparedness of the project. Investors think the longer delivery time, the less preparation and confidence of fundraisers. Using regression analysis, Hu [72] found a negative correlation between delivery time and crowdfunding success. The estimated delivery time affects investors’ strategies, expectations, and eventual satisfaction [70]. The longer the delivery time is, the lower the possibility of financing success, indicating that a long delivery time reduces investors’ investment willingness. The above conclusions imply that the length of delivery time affects investors’ investment decisions. Therefore, in this study, delivery time can serve as a prerequisite and interact with other variables in multiple paths to achieve project success. Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Delivery time would serve as an antecedent condition and can be combined with other causal conditions to influence the success of crowdfunding projects.

3.2.2. Funding Goal

Before the launch of crowdfunding projects, it is necessary to set a funding goal. In the All-or-Nothing model, if the final amount of funding reaches the initial target, the project is successful; otherwise, it fails. Another way to measure project success is to compare the ratio of the final amount raised to the target amount. If the ratio exceeds 1, the project succeeds. The greater the ratio, the more successful the project [73]. Using regression analysis, Huang [74] found that the funding goal negatively correlates with project success. For investors, a lower funding goal may result in awards not being delivered, and a higher funding goal may result in projects that are not successful [18]. It is therefore important to set an appropriate funding goal. Thus, this research argues that the funding goal would be part of the antecedent conditions to achieve project success.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Funding goals would serve as an antecedent condition and can be combined with other causal conditions to influence the success of crowdfunding projects.

Based on the above assumptions, we propose the following configuration model, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A configurational model.

4. Methods

4.1. Data Collection

The data of this study come from 8 types of crowdfunding projects on JD crowdfunding. The prediction variables and response variables of this study were constructed from the campaign page of JD crowdfunding projects. On the JD crowdfunding website, the project is successful when the final fundraising amount exceeds the fundraising goal during the crowdfunding period. Successful crowdfunding projects will deliver all promised rewards within the delivery time. If a project does not raise enough funds within the limited time, it is considered to fail. In this study, both successful and failed projects are included for analysis.

JD crowdfunding began to operate in July 2014 and became a larger crowdfunding platform. In 2015, it entered a period of rapid development, during which the platform developed steadily and various regulations began to improve. Our purpose is to find effective configurations that make the crowdfunding project successful. Therefore, all 1042 crowdfunding projects from April 2015 to May 2016 are analyzed. Table 1 shows the types of crowdfunding projects. Technical crowdfunding projects account for the largest proportion, reaching 55.662%, followed by design projects, accounting for 13.244%. Publication crowdfunding accounts for the smallest proportion: only 1.152%. Green supply chain management is mainly applied to technical projects. As technical projects cover the whole process of design, material procurement, production and marketing, this study focuses on technical crowdfunding, with a sample size of 580. The QCA method is considered to be a sufficient sample size.

Table 1.

The types of crowdfunding projects.

4.2. Predictive Variables

Because the projects on the JD crowdfunding platform are mainly introduced through various pictures, we employed text recognition technology to extract the text from the picture. This paper focused on four parts of the green supply chain: green design, green material, green production, and green marketing. Based on the available data and literature, we extracted the keywords and constructed a vocabulary (see Table 2 for details). When a word of a certain category in the vocabulary was mentioned in the project introduction, we assigned 1 to the variable and 0 otherwise. Quantitative data on delivery time and funding goals were retrieved and converted into binary according to medians for further analysis by QCA.

Table 2.

Green supply chain vocabulary.

4.3. Response Variable (Outcomes)

The response variable is a binary variable, indicating whether the crowdfunding project is successful. At the end of crowdfunding, projects whose progress is greater than or equal to 100% show that crowdfunding is successful with a value of 1; otherwise, crowdfunding fails with a value of 0. The above information is accessible because real-time fundraising data enable project fundraisers and investors to clearly understand project progress.

4.4. QCA Method

As a qualitative analysis method, QCA is suitable for analyzing configuration problems. QCA is mainly classified as clear set QCA (csQCA), multi-valued set QCA (mvQCA) and fuzzy set QCA (fsQCA). csQCA is used to analyze dichotomous variables, and the variable assignment is 1 or 0, indicating that the state exists or lacks. FsQCA overcomes the defect that the variable is a binary variable and can better avoid missing data in the conversion process [82].

This study used QCA to analyze the complex causal relationship between the combination of antecedent conditions and results by using truth tables to assess causality between antecedent conditions and results. Calibrating raw data is a prerequisite for fuzzy sets. Through calibration, variables generated fuzzy set-membership scores, and data were calibrated to generate values ranging from 0 to 1. During calibration, we set three thresholds: full membership, full non-membership, and crossover point. The calibration standards were 95%, 5% and 50% quantiles of the data, respectively [35]. The calculations of the calibration for the membership scores were performed using QCA Software. Using QCA software, the data were converted into a ‘truth table’, which shows all possible configurations of antecedent conditions that affect project success.

QCA is a set theory analysis method that analyzes the relationship between the condition set and the result set in the case. The set analysis mainly includes two aspects: the necessity of a single condition and the sufficiency of the combination of antecedent conditions. Consistency and coverage can help explain the necessity of a single condition and the sufficiency of the combination of conditions. A single condition is necessary to test whether the result set is a subset of the condition set: that is, to measure whether a single condition is necessary for the result [34]. It is generally believed that a single conditional necessity exists when the consistency is greater than 0.9 [34]. The sufficiency of conditional combinations is to check whether the antecedent conditional combination is a subset of the result set. In the early literature, the consistency threshold was set to 0.75. Subsequently, Fiss [49] used 0.8 as the consistency threshold, which is also the standard used in most current studies. Raw coverage measures the explanatory degree of each configuration to the results. Unique coverage measures the number of cases that can only be explained by the configuration. Solution coverage measures the explanatory degree of all configurations to the results. High coverage means that configurational models explain the most successful cases [40].

In QCA analysis, the selection of case samples, data calibration, adjustment parameters, case frequency threshold and consistency threshold are set by researchers according to research problems and empirical knowledge. Their setting is subjective, and different operations lead to different results. It is particularly important to evaluate the stability of the configuration path generated by the currently selected parameters. In multiple regression, if different models and samples are replaced, the significance, sign and relationship strength of the coefficient do not change significantly; then, it can be determined that the influence of relevant variables on the results is significant. Similar to the test method in multiple regression, if you want to evaluate the robustness of QCA results, you should consider two aspects: one is the selection of indicators, and the other is the operation selection to change the results of these indicators. At present, scholars at home and abroad mainly use three methods to test the robustness of the results: changing the calibration method of variables, changing the case frequency and consistency threshold, and deleting the number of cases. After the robustness test, if the configuration models obtained have similar configuration path, coverage value and consistency value to the original model, the original models are considered to be robust. “Similarity” means that the solution set after robustness test is the same as the original solution set, or there is a subset of the original solution set, and there is no significant difference from the original solution set.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics of variables. It provides the mean, standard deviation, maximum and minimum of green design, green materials, green production, green marketing, delivery time and funding goals. Table 3 shows that the maximum of each factor in the green supply chain is 1, and the minimum value is 0. The maximum value of delivery time is 90, the minimum value is 3, the average value is 27.133, and the standard deviation is 9.880, indicating that the delivery time of different projects is significantly different. The maximum value of the funding target is 5,000,000, the minimum value is 5000, the average value is 171,846.4, and the standard deviation is 476,001.5, indicating that the funding goals of each project have significant differences.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics on variables.

5.2. Configurational Models

Table 4 shows the results of the necessary analysis for a single condition. The consistency of each condition is less than 0.9, indicating that the occurrence of the results is not only dependent on a certain condition variable but is affected by multiple conditional variables. Therefore, it is necessary to study the influence of the combination of multiple antecedent conditions on the results.

Table 4.

Analysis of necessary conditions.

Table 5 shows the configurational models that support the success of the project. In Table 5, the consistency values of all configurational models exceed 0.8, and the coverages do not exceed 0.65, indicating that the conditional configuration is a sufficient condition for the success of the project. The green design appears in one of the five models with a coverage value of 0.025 and a consistency value of 0.897, indicating that the combination of green design and other factors has an impact on project success. Therefore, the result supports H1. Green material appears in two of the five models with coverage values of 0.008 and 0.014 and consistency values of 0.867 and 0.892, indicating that the combination of green material with other conditions has an impact on the success of the project. Therefore, the parameters support H2. Green production appears in three of the five models with coverage values ranging from 0.008 to 0.025 and consistency values ranging from 0.847 to 0.897, indicating the importance of green production for project success. Therefore, the parameters support H3. Green marketing appears in two of the five models with coverage values ranging from 0.014 and 0.0248 and consistency values of 0.847 and 0.893, indicating that green marketing combined with other conditions has an impact on the results. Therefore, the result supports H4. The delivery time appears in two models with coverage values of 0.008 and 0.025 and consistency value values of 0.867 and 0.897, indicating that the delivery time combined with other conditions has an impact on the results. Therefore, the parameters support H5. The funding goal appeared in three models with coverage values ranging from 0.008 to 0.025 and consistency values ranging from 0.847 to 0.893, indicating that the combination of funding goals and other conditions has an impact on the success of the project. Therefore, the study supports H6.

Table 5.

Configuration models for success.

Configuration 1 in Table 5 shows that projects that do not involve green design, green materials, green production or green marketing have lower funding goals to support the success of crowdfunding projects. Model 1 sets a lower funding goal to reduce the adverse effects of a lack of green design, green materials, green production and green marketing. Because of the lack of green design, the enterprise did not consider the environmental friendliness and cost of the whole product life cycle in the early stage of project preparation. Green materials are not used in the project, and there is no need to consider the higher cost of using environmentally friendly materials over ordinary materials. At the same time, there is no need to consider the additional charges of using green production and green marketing. The fundraiser wants to reach the fundraising amount as soon as possible to promote the project’s success. This conclusion supports the conclusion of the previous crowdfunding operation and management model: that is, a lower funding goal can promote the success of crowdfunding projects [18]. Model 1 shows that when the project does not mention any green supply chain factors, the success of the project can be achieved by setting a low funding goal. This may be because investors fully understand the time and money costs of using green supply chains, so when the project succeeds as soon as possible, consumers are more tolerant of whether to include green supply chains. Model 1 applies to enterprises with low funding goals that wish to receive financing amounts as soon as possible.

Model 2 shows that for projects involving green design and green production, fundraisers need to configure a longer delivery time to support the success of crowdfunding projects. Model 2 shows that consumers can accept long delivery times to support green design and green production. A longer delivery time gives the enterprise enough time to carry out green design, considering the greenness of products from the perspective of the whole life cycle, looking for and adopting more reasonable and optimized schemes to minimize resource consumption and negative environmental impacts [59]. In the process of green production, it may take sufficient time to improve equipment and processes and develop green technology. In green production, transforming technology into productive sales products is a complex process, and there may be problems such as information transmission. Accordingly, a longer delivery time gives companies enough time to address technical barriers [83]. Model 2 shows that when the project mentioned the factors of the green supply chain, even if the project had a longer delivery time, the project could be successful. This shows that when the product meets the requirements of green development, consumers are more tolerant of longer delivery times.

Model 3 shows that projects that do not involve green design but involve green materials and green marketing configure a shorter delivery time and a higher funding goal to achieve the success of crowdfunding projects. Model 4 shows that projects that involve green production and green marketing, a shorter delivery time and a higher funding goal would support the success of crowdfunding projects. Models 3 and 4 show that crowdfunding projects require higher funding goals to support green materials, green production and green marketing, and shorter delivery times can support the implementation of green marketing. Companies need to find environmentally friendly materials, which increases additional costs for companies [61]. Green production often requires innovation and new technology, and a large amount of capital investment is needed in the early stage of technological innovation. Technological innovation requires a large amount of capital investment in the early stage. In green marketing, it is necessary to invest money in the whole marketing process to carry out the overall environmental protection planning. Although green logistics can slightly reduce costs in some ways, due to the high cost of green packaging, the overall cost of green marketing is increased, so it is necessary to set a higher funding goal to support the success of the project. Although it takes time to establish green marketing channels when implementing green marketing, enterprises can effectively shorten the marketing time by directly docking partners and reducing intermediaries [84]. In addition, green marketing can make full use of the Internet to reduce marketing time compared with the traditional marketing method of issuing leaflets. For projects involving the green supply chain, consumers are more tolerant of financing objectives and willing to pay higher investments to support the development of the green industry [63]. Models 3 and 4 support Cumming’s conclusion that clean technology crowdfunding projects may have a higher funding goal [29]. Models 3 and 4 are suitable for companies that have begun to improve competitiveness and pursue sustainable development.

Model 5 shows that projects that involve green materials and green production but do not involve green design configure a longer delivery time and a higher funding goal to achieve the success of crowdfunding projects. Model 5 shows that for projects containing green materials and green production, setting longer delivery times and higher funding goals to obtain sufficient time and financing amounts would promote the success of the project. Enterprises can design and develop new materials based on the basic concept of green materials. For traditional materials, enterprises can also carry out ecological environmental transformation. New type green materials may have insufficient output, so they reserve a long time to achieve on-time delivery. Green production also takes enough time for technological innovation [80]. Models 3–5 support the existing literature indicating that the innovation of products requires capital investment [83]. Models 3–5 illustrate that even with a high funding goal, projects can succeed, indicating that the introduction of green supply chains attracts more investors to pay attention to the green supply chain or that funders are willing to provide more funds to support the development of the green industry.

5.3. Robustness Test

In the robustness test method mentioned above, the first and second test methods are mainly used in this study; that is, we change the consistency threshold, case frequency threshold and data calibration strategy to check the robustness of the results. The results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Robustness test summary.

First, we used a higher consistency threshold (0.83) and a lower threshold (0.81) in QCA analysis. The results show that with the increase in the consistency threshold, the overall consistency value of the solution increases, but the coverage value decreases. In addition, when the consistency threshold is 0.83, four paths appear the same as the original path; when the consistency threshold is 0.81, two new paths appear, but the original five paths appear.

To evaluate the robustness of the results when changing the case frequency threshold, we set the case frequency threshold to 5 and 7. The results show that when the case frequency threshold is 5, the overall coverage and consistency increase slightly, and two new paths appear, but the original five paths appear. When the case frequency threshold is 7, the same path as the original result appears. When the case frequency threshold is 7, the same path as the original result appears.

We changed the calibration anchor of the data and recalibrated the variables. The upper bound (full membership point) and lower bound (full non-membership point) are changed to 100% and 0%, and the results are the same as the original results, but the overall coverage value increases slightly and the overall consistency value decreases slightly.

To sum up, with the changes in consistency threshold, case frequency threshold and calibration strategy, no robustness test shows a significant difference from the original solution. We can conclude that the results are robust.

5.4. Configuration Model for Successful Crowdfunding of Functional and Hedonic Products

In this study, products in crowdfunding campaigns are divided into functional products and hedonic products according to the functions, application situations and attributes of products in crowdfunding projects [85]. Functional products mainly provide consumers with functional benefits and values to help consumers obtain certain functions or achieve certain purposes, which can meet the functional needs of consumers. Hedonic products mainly provide consumers with emotional or other sensory experiences, which can make consumers produce sensory pleasure, fantasy or entertainment products or services, meet certain emotional needs of consumers, and provide consumers with experiential value [85]. It can be seen that consumers purchase functional products mainly for a tool to achieve some purposes, and its impact is tangible, while the purchase of hedonic products is to obtain the experience or emotional value brought by the product, and its impact is usually invisible. In this study, technical crowdfunding projects are divided into those for functional products and for hedonic products to explore the differences in the configuration paths between different product types. There are 450 crowdfunding projects for functional products and 130 crowdfunding projects for hedonic products. It can be seen that the crowdfunding projects for functional products are the main projects in technical crowdfunding projects.

Table 7 and Table 8 show the results of the necessity analysis of individual conditions for functional and hedonic products. It can be seen from the results that the consistency of the six condition variables of the two products is less than 0.9, indicating that the necessity test of each condition variable is not passed; that is, each antecedent condition is not a necessary condition for the result, and the result is affected by multiple condition variables. Therefore, it is essential to study the influence of the combination of antecedent conditions on the results.

Table 7.

Necessity test for variables (functional products).

Table 8.

Necessity test for variables (hedonic products).

Table 9 shows the configuration model for the success of crowdfunding projects for functional and hedonic products. The consistency values of all configuration models exceed 0.8, indicating that the configuration among conditional variables is the sufficient condition for the success of crowdfunding projects.

Table 9.

Configuration models.

For functional products, Model 1 shows that when the crowdfunding project does not include the elements of the green supply chain, the project can succeed regardless of the configuration of delivery time and funding goal. These investors are more concerned about the function of the product and whether the functions can meet their needs. Models 2–4 show that when the project contains the elements of a green supply chain, it is necessary to configure the corresponding delivery time and funding goal to make the crowdfunding project successful. Models 3 and 4 show that when the project involves green design, green materials and green production, without green marketing, it requires a higher funding goal to support the success of the project. At this time, the sponsors need enough time to find environmentally friendly green materials to replace the previous materials. On the other hand, some raw materials of functional products need green certification when they are used, so the sponsors need enough time to carry out the certification. In the green production of products, the sponsors need sufficient funds to carry out the greening of technology and increase the functionality of the products. The sponsors need enough time to consider the greening of the whole product line from a holistic perspective when carrying out green design. Model 2 shows that the sponsors need enough funds to support the high cost of green materials. At this time, green marketing and green transportation can effectively shorten the time compared to traditional media publicity and transportation.

Compared with functional products, investors pay more attention to the green elements of hedonic products, and they are willing to tolerate a longer delivery time and a higher funding goal to support the greening of products. Models 1–3 show that when green materials and green production are involved in the project, it is necessary to configure a longer delivery time and a higher funding goal to support the success of crowdfunding projects. The sponsors need sufficient time to find green materials, which add extra costs compared to previous materials, so they need enough funds to support using green materials. The sponsors need sufficient funds to cover the cost of equipment modification for cleaner production. Through green logistics, the sponsor rationally allocates distribution centers and implements joint and consistent transportation, which can effectively reduce transportation time, improve distribution services, greatly reduce inventory, even achieve “zero” inventory, and reduce logistics costs. Model 4 shows that when green design and green production are involved in the project, the sponsor needs to configure a longer delivery time and a higher funding goal to support the success of the crowdfunding project.

6. Conclusions

This research has made contributions to the research of crowdfunding and investigated the implementation of crowdfunding projects from the perspective of the green supply chain. The research on crowdfunding projects is no longer limited to project characteristics, fundraisers and investors, which enriches the research in the field of crowdfunding. Based on the data collected from the JD crowdfunding platform, this study examines the impact of the green supply chain (green design, green materials, green production, green marketing) and crowdfunding project characteristics (delivery time, funding goal) on project success. We propose prerequisites for successful crowdfunding based on the literature on green supply chains and crowdfunding. This study evaluates the greening of every link of product life cycle by building a vocabulary related to the green supply chain. Using the QCA method on technical crowdfunding projects, we found several configurational models that lead to crowdfunding success. For some sponsors who are short of funds and who want to pursue green products, this study provides some important insights: that is, they can attract investors by going green in a certain part of products. Different from previous symmetry studies, this study utilized the QCA method to provide more paths for project success.

Most of the previous empirical studies used symmetric tools, such as regression analysis, which only reported the fitting validity and did not report the predictive validity. According to Gigerenzer and Brighton, a model with good fitting validity does not mean that the model has good prediction ability [86]. This study tested the predictive validity by adjusting the parameter threshold and changing the data calibration method. The results show that the model has good predictive validity.

Theoretically, this study provides insights into the complex interactions among green supply chains, delivery time, financing objectives and crowdfunding results. This study supports set theory by verifying the set relationship between condition sets and result sets through the necessity test of a single antecedent condition and the sufficiency test of the condition configuration. This study supports the complexity theory and provides empirical analysis to deeply understand the complex interaction of the green supply chain, delivery time, financing objectives and crowdfunding success. Researchers in marketing and management contend that complexity theory serves as a useful foundation for building and testing theory beyond symmetric perspectives [87]. This study adopts an overall perspective and is not limited to a single antecedent condition. The QCA results of successful crowdfunding projects verify that a single antecedent condition is difficult to lead to a result, and the configuration model that meets the consistency of conditions and coverage can predict the occurrence of the result.

In practice, this study provides some enlightenment for multiple stakeholders in crowdfunding. For crowdfunding platforms, configurational models provide them with useful suggestions to face projects that are or will be launched. For fundraisers, the results of this study provide a reliable reference for the setting of a green supply chain, crowdfunding delivery time and funding goal, helping them choose the best solution to make the project successful. Suppose the fundraiser does not want to implement green supply chain management in crowdfunding projects and wants to acquire investment as soon as possible. In that case, it is necessary to allocate a short delivery time in crowdfunding projects to remind investors that they will receive returns as soon as possible to attract consumers to invest. If fundraisers want to implement green supply chain management in crowdfunding projects, they need to adjust the delivery time and funding goal. For some fundraisers with green supply chain management experience, they can set a short delivery time in crowdfunding projects to attract investors with green consciousness. At this time, due to the short delivery time, even if there is a high funding goal, it may attract investors without green consciousness. For fundraisers who want to improve competitiveness and pursue green development, sufficient funds are needed to support green technology innovation, and a high funding goal can be allocated in crowdfunding projects. For investors, it reminds them to pay attention to the description and setting of the project before investing. If investors do not have green consciousness, they should pay more attention to the delivery time and funding goal. For investors with green awareness, they are more tolerant of delivery time and financing amount. At this time, they no longer focus on whether they can acquire returns quickly, but on the green supply chain management implemented by fundraisers. Meanwhile, crowdfunding platforms should encourage project sponsors to make adequate preparations and plans before starting crowdfunding to attract more investors who pay attention to the green supply chain.

However, this study has certain limitations. QCA and its reliance on the two-element Boolean algebra limits scholars in three ways. Firstly, compared with the quantitative method based on general Boolean algebra, two-element Boolean algebra limits the interaction between sets. Secondly, two-element Boolean algebra is a weak model of propositional logic, which cannot deal with modern social science theory. Third, researchers use QCA to describe causality only from the aspects of necessity, sufficiency and INUS conditions, but counterfactual cannot be explained by causality [88]. As to the variable selection, due to the limitation of the sample size, this paper only selects two critical variables, which are the delivery time and the funding goal of the crowdfunding project. We know that there are other variables which might have an impact on the success of crowdfunding, so in the next step, we will select other variables about crowdfunding characteristics to explore the impact of the interaction between the various elements of the green supply chain and other variables on the success of crowdfunding. The research samples in this paper are from technical crowdfunding projects on the JD crowdfunding platform and have not studied all types of projects. Therefore, this study’s conclusions are limited and unsuitable for all types of crowdfunding projects. In addition, as the largest crowdfunding website platform in China, JD Crowdfunding has a huge user base, but there are other crowdfunding website platforms in China. Whether the research conclusion can be used in crowdfunding projects on other crowdfunding websites remains to be verified. It is hoped that after more data are collected, other types of projects and projects on other platforms can be analyzed to verify the scalability of current research findings. In addition, studies have been provided insights on the role of environmental policies in promoting venture capital (VC) investments in companies involved in the development of clean technologies [89]. Therefore, we hope to explore the impact of environmental policies on consumer investment and consumption behavior and crowdfunding results in the next step.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and W.Y.; methodology, L.W.; software, L.W.; validation, L.W.; formal analysis, L.W. and W.Y.; investigation, L.W.; resources, L.W. and Y.Z.; data curation, L.W. and F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review and editing, W.Y. and Y.Z.; visualization, L.W.; supervision, W.Y.; project administration, W.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2021SRY05), Education and Teaching Research Project of Beijing Forestry University (BJFU2022JY037) and Major Project of National Forestry and Grassland Administration of China (2019132707).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study are publicly accessible on the JD crowdfunding website.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Han, H. Theory of green purchase behavior (TGPB): A new theory for sustainable consumption of green hotel and green restaurant products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2815–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummala, V.; Phillips, C.; Johnson, M. Assessing supply chain management success factors: A case study. Supply Chain Management. 2016, 11, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of Consumer Environmental Responsibility on Green Consumption Behavior in China: The Role of Environmental Concern and Price Sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green Consumption: Behavior and Norms. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defazio, D.; Franzoni, C.; Rossi-Lamastra, C. How Pro-social Framing Affects the Success of Crowdfunding Projects: The Role of Emphasis and Information Crowdedness. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 171, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-Y.; Tu, J.-C.; Gu, S.; Lu, T.-H.; Yi, M. Construct and Priority Ranking of Factors Affecting Crowdfunding for Green Products. Processes 2022, 10, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handfield, R.B.; Walton, S.V.; Goizueta, R.C.; Seegers, L.K.; Melnyk, S.A. ‘Green’ supply chain: Best practices from the furniture industry. In Proceedings of the 1996 27th Annual Meeting of the Decision Sciences Institute, Orlando, FL, USA, 24–26 November 1996; Volume 3, pp. 1295–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H. Green supply chain management—Direction of business management. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2000, 4, 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Plambeck, E.; Lee, H.L.; Yatsko, P. Improving Environmental Performance in Your Chinese Supply Chain. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Despoudi, S.; Papaioannou, G.; Saridakis, G.; Dani, S. Does Collaboration Pay in Agricultural Supply Chain? An Empirical Approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 4396–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Cagliano, R. Inclusive environmental disclosure practices and firm performance: The role of green supply chain management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 1815–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, P.D.; Lawson, B.; Petersen, K.J.; Fugate, B. Investigating green supply chain management practices and performance: The moderating roles of supply chain ecocentricity and traceability. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 39, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. Green supply chain behavior and business performance: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 144, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Hu, Z.; Wiwattanakornwong, K. Unleashing the role of top management and government support in green supply chain management and sustainable development goals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8210–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Institutional-based antecedents and performance outcomes of internal and external green supply chain management practices. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2013, 19, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, J. The microfinance promises. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 1569–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetz, M.K.; Schreier, M. The Value of Crowdsourcing: Can Users Really Compete with Professionals in Generating New Product Ideas? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E. The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yan, X.; Chen, Y. Configurational Path to Financing Performance of Crowdfunding Projects Using Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Eng. Econ. 2017, 28, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Crowdfunding|Digital Markets-Market forecast for Crowdfunding Worldwide Through[EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/335/100/crowdfunding/worldwide#market-users (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Kuppuswamy, V.; Bayus, B.L. Does my contribution to your crowdfunding project matter? J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglo, A.; Miglo, V. Market imperfections and crowdfunding. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.; Grigore, G.; Molesworth, M. Success in the management of crowdfunding projects in the creative industries. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cao, S. Research on factors influencing supporters’ decision-making in award-based crowdfunding based on “dream” platform. Int. Bus. 2018, 2, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, K.; Catalini, C.; Goldfarb, A. Crowdfunding: Geography, Social Networks, and the Timing of Investment Decisions. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2015, 24, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Franzoni, C.; Rossi-Lamastra, C. Internal Social Capital and the Attraction of Early Contributions in Crowdfunding. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Lau, R.Y.K.; Xu, W. The determinants of crowdfunding success: A semantic text analytics approach. Decis. Support Syst. Arch. 2016, 91, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemer, J. A snapshot on crowdfunding. Work. Pap. Res. Pap. Econ. 2011, 39, 1438–9843. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, D.J.; Leboeuf, G.; Schwienbacher, A. Crowdfunding cleantech. Energy Econ. 2017, 65, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ppo, A.; Nm, B. The combined effect of success factors in crowdfunding of cleantech projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132921. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Rahman, M.K.; Rana, M.S. Predicting Consumer Green Product Purchase Attitudes and Behavioral Intention During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 25, 760051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B.; Ragin, C.C. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (Qca) and Related Techniques; Sage Publications Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C. Fuzzy-set social science. Contemp. Sociol. 2000, 30, 291–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frydrych, D.; Bock, A.J.; Kinder, T.; Koeck, B. Exploring entrepreneurial legitimacy in reward-based crowdfunding. Ventur. Cap. Int. J. Entrep. Financ. 2014, 16, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholakova, M.; Clarysse, B. Does the possibility to make equity investments in crowdfunding projects crowd out reward-based investments? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Shen, J.; Hahn, J. How Rewarding Are Your Rewards? A Value-Based View of Crowdfunding Rewards and Crowdfunding Performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 562–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Tan, X.; Dong, M.; Qi, J. How to Design Your Project in the Online Crowdfunding Market? Evidence from Kickstarter. In Proceedings of the Thirty Fifth International Conference on Information Systems, Auckland, New Zealand, 14–17 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lagazio, C.; Querci, F. Exploring the multi-sided nature of crowdfunding campaign success. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zheng, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, T. Configurational paths to sponsor satisfaction in crowdfunding. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvilichovsky, D.; Inbar, Y.; Barzilay, O. Playing Both Sides of the Market: Success and Reciprocity on Crowdfunding Platforms. Int. Conf. Inf. Syst. 2013, 4, 3052–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Xue, Y.W.; Wang, W.L. A dynamic analysis of the investment behavior of backers in crowd-funding financing based on performing arts crowd-funding. J. Guangdong Univ. Financ. Econ. 2016, 31, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Beamon, B.M. Designing the green supply chain. Logist. Inf. Manag. 1999, 12, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.H. An Organizational Theoretic Review of Green Supply Chain Management Literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, V.; Robert, D.K. Extending green practices across the Supply chain. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 26, 795–821. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, F.F.; Barbosa-Povoa, A.P.; Butturi, M.A.; Marinelli, S.; Sellitto, M.A. Green Supply Chain Management: Conceptual Framework and Models for Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, V.D.R.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. OR FORUM—The Evolution of Closed-Loop Supply Chain Research. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, A.; Craig, R. Using neo-institutionalism to advance social and environmental accounting. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2011, 21, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building Better Causal Theories: A Fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannacci, F.; Cornford, T. Unravelling causal and temporal influences underpinning monitoring systems success: A typological approach. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattke, J.; Maier, C.; Reis, L.; Weitzel, T. Bitcoin investment: A mixed methods study of investment motivations. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishant, R.; Ravishankar, M.N. QCA and the harnessing of unstructured qualitative data. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 845–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, G.; Feng, Y.; Sarpong, S. A configurational model of reward-based crowdfunding project characteristics and operational approaches to delivery performance. Decis. Support Syst. 2019, 120, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezen, B.; Çankaya, S.Y. Green Supply Chain Management Theory and Practices. In Operations and Service Management: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón Vargas, J.R.; Moreno Mantilla, C.E.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Enablers of sustainable supply chain management and its effect on competitive advantage in the Colombian context. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, P.Y.; Lee, V.H.; Tan, W.H. A gateway to realising sustainability performance via green supply chain management practices: A PLS-ANN approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 107, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowie, T. Green design. World Cl. Des. Manuf. 1994, 1, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, G. Material selection for green product design. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 1996, 1, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Chiu, A.S.F.; Tan, R.R.; Siriban-Manalang, A.B. Sustainable consumption and production for Asia: Sustainability through green design and practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A.; Xiao, X. Multiple attribute decision making on green materials based on life cycle assessment. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 2012, 31, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, X.Y. Research on the Selection and Evaluation Content of Green Materials. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 721, 622–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K. Green supply-chain management: A state-of-the-art literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.; Florkowski, W.J.; Brückner, B.; Schonhof, I. Willingness to Pay for Environmental Practices: Implications for Eco-Labeling. Land Econ. 2002, 78, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. How green production might sustain the world. ILLAHEE-J. Northwest Environ. 1994, 10, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, N.; Lindsey-Mullikin, J.; Krishnan, R. An analysis of consumer reactions to green strategies. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2013, 22, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Towards Sustainability: The Third Age of Green Marketing. Mark. Rev. 2001, 2, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Smith, J.S.; Gleim, M.R.; Ramirez, E.; Martinez, J.D. Green marketing strategies: An examination of stakeholders and the opportunities they present. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, R.; Deoranto, P.; Wicaksono, M.L.A.; Nazzal, A. Green marketing mix: An example of its influences on purchasing decision. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 733, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, J. The clearer timelines, the better? Evidence from Kickstarter. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, J.A.; Chimahusky, S. Are promises meaningless in an uncertain crowdfunding environment. Econ. Inq. 2016, 54, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Han, K. Deconstruction of Online Crowdfunding Performance from the Perspective of Information Asymmetry. Financ. Trade Econ. 2020, 41, 100–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, T.; Schwienbacher, A. An empirical Analysis of Crowdfunding. Electron. J. 2010, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Q.; Chen, H.; Da-Ye, L.I. Research on factors influencing the success of crowd funding projects: The perspective of customer value. China Soft Sci. 2015, 6, 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.; Xiong, X.F. Study on the Design Process Based on Green Design. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2011, 130–134, 1298–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.Y.; Yuan, M.H.; Cheng, S.; Ji, A.M. Green Design Methods Based on Product Configuration. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 343–347, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhu, D. Organic Thermoelectric Materials: Emerging Green Energy Materials Converting Heat to Electricity Directly and Efficiently. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6829–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varbanov, P.S.; Jia, X.; Lim, J.S. Process Assessment, Integration and Optimization: The Path towards Cleaner Production. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 124602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]