The Alchemy of Coaching: Psychological Capital as HERO within Coaches’ Selves

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Psychological Capital

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design, Sampling, Data Collection and Ethical Considerations

3.2. Data Analysis

3.3. Validity and Reliability

4. Findings

4.1. A Sense of Responsibility

4.1.1. Responsibility to Others

“I stepped down and left my previous position as a lecturer. When I was a lecturer, I saw there was a need for me to make a change... so I left my career as a lecturer”(Ahmad)

“During my time at the Teacher Training Institute, I have always wondered, once they have finished their training at Teacher Training Institute, can they practice what they have learnt?”(Sheila)

“My only aim is to make my state successful. I came back serving my state so I can contribute back and guide the teachers to be at par with those at the international level”(Asyikin)

4.1.2. Realising the Skills and Quality in Self

“When the ministry first announced this IC position and knowing the role and task it had to do which is to guide teachers, I saw the potential in me, that I believe I have the criteria as well as the knowledge that I can share with the teachers”(Sheila)

“I have the ability to know people because I am very experienced and have been involved in teaching and training for a long time”(Ahmad)

4.2. Positive Resources

4.2.1. Keeping a Positive Mind

“Challenges are the foundation of our success. There is no success without challenges. The challenges make us think. We can never be successful if we are too comfortable”(Ahmad)

“The tasks we need to do keep changing and this becomes a motivation for me to keep being an IC”(Sheila)

“I have always put aside negative elements. I told myself, ‘Not me, not me, not me. It’s not me! I’m a very positive person’”(Asyikin)

“It gave me so much pressure that I was prescribed hypertension medication. I have never had hypertension before!”(Zaiton)

“In the end, it (the heated discussion with teachers) turned out to be a good event. One thing is probably because I am much older than them. It’s also because I never forced them to follow my way of doing, and I never handle things negatively”(Zaiton)

4.2.2. Positive Attitude and Behaviour

“Since they have been throwing bad words at me, I decided to change the strategy of approaching them. What I did was, I said to them, ‘Alright, since you are so mad having me here to coach you, go on and say what you wanted to say first’. I used that kind of approach and I’m cool with that”(Zaiton)

“Even our SOP highlighted that we (as IC) cannot force teachers who do not want to be coached. That was the concept. We cannot force them”(Yahya)

“Our personality, we need to be humble. We want to coach people, of course we need to have humanistic characteristics”(Asyikin)

“We, as IC need to be honest. We need to gain their trust or else. And once we lose their trust, they are never going to believe us”(Ahmad)

4.3. Work Commitment

4.3.1. Knowledge-Seeking Behaviour

“To be a successful coach, I have to know the principles of counselling. I have to learn, I have to read”(Ahmad)

4.3.2. Have Goals Set in Mind and Work Hard in Achieving Those Goals

“If possible, I want to make Temerloh (state) number one again as to how it was before. Previously when I was a GC (Guru Cemerlang/Excellent Teacher), Temerloh (state) was in the first place in academic achievement in Pahang”(Siti)

“I set as many goals as I can and one of those is to make the state that I serve successful. The aim that I set up every year is, ‘What can I do for my PPD (district office)? What can I do for my organisation? What can I do to my coachees?’ And this year, I managed to develop a module for my coachees. I even created (learning) games”(Asyikin)

“My aim is to produce quality teachers so they can further help the students to become excellent”(Zaiton)

4.3.3. Job as Calling

“I love my job. It is because, when I enjoy what I’m doing, I will find a solution to whatever issue that comes ahead”(Asyikin)

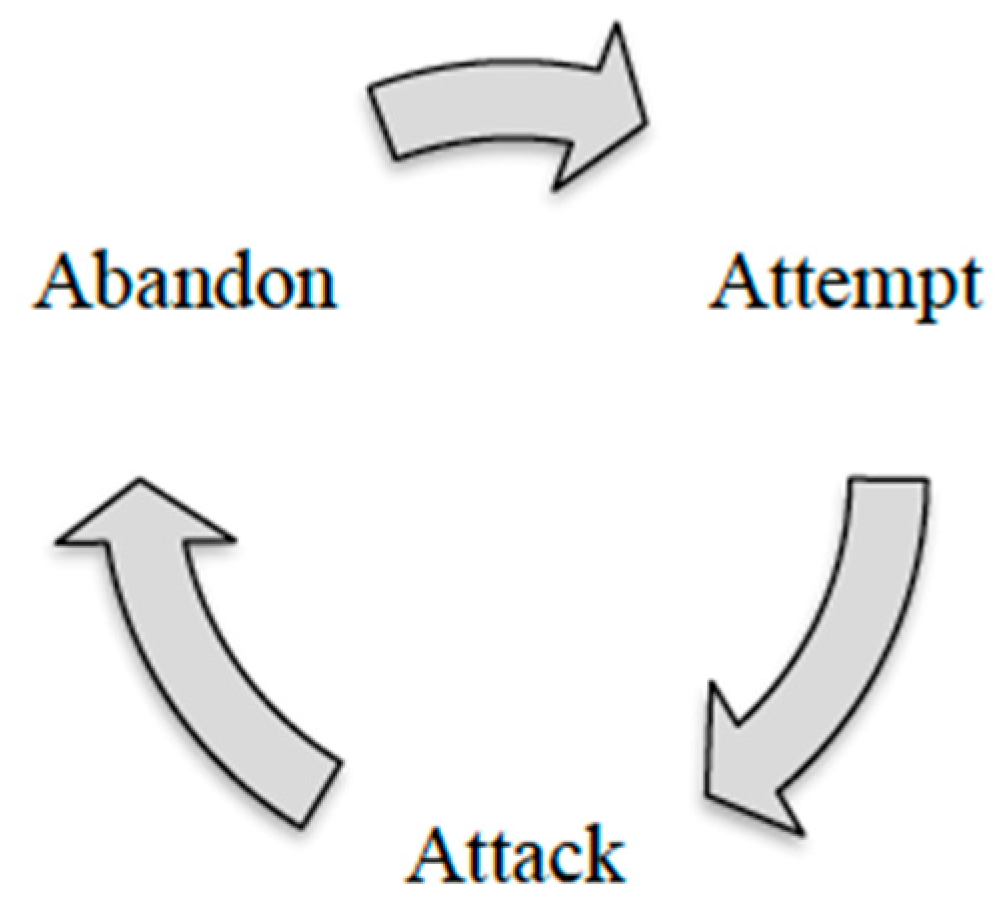

5. Discussion

5.1. A Sense of Responsibility

5.2. Positive Resources

5.3. Work Commitment

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seligman, M.E.P. Building Human Strengths: Psychology’s Forgotten Mission; APA Monitor: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, S.; Whybrow, A. Coaching psychology: An introduction. In Handbook of Coaching Psychology: A Guide for Practitioners; Palmer, S., Whybrow, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M.; Green, L.S.; Rynsaardt, J. Developmental coaching for high school teachers: Executive coaching goes to school. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2010, 62, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.J. The role of contracting in coaching: Balancing individual client and organizational issues. In Handbook of the Psychology of Coaching and Mentoring; Passmore, J., Peterson, D.B., Friere, T., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Heineke, S.F. Coaching discourse: Supporting teachers’ professional learning. Elem. Sch. J. 2013, 113, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzimiri, R.; Burroughs, E.A.; Luebeck, J.; Sutton, J.; Yopp, D. A look inside mathematics coaching: Roles, content, and dynamics. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2014, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, F.A. The role of the English learner facilitator in developing teacher capacity for the instruction of English learners. Teach. Teach. 2017, 23, 312–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanita, P. Instructional Coaches as Teacher Leaders: Roles, Challenges, and Facilitative Factors. Ph.D. Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Mei, J.; Zhu, Y. Feedback-Seeking Behaviour: Feedback Cognition as a Mediator. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2017, 45, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, S.H.; Saeed, K.M.; Mohamed, A.R. Instructional coaching as a tool for professional development: Coaches’ roles and considerations. Qual. Rep. 2019, 24, 1106–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. Unmistakable Impact: A Partnership Approach for Dramatically Improving Instruction; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borman, J.; Feger, S. Instructional Coaching: Key Themes from the Literature; The Education Alliance at Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M.; Knight, J. Coaches as system leaders. Educ. Leadersh. 2011, 69, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, A. Making Our Own Road: The Emergence of School-Based Staff Developers in America’s Public Schools; The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Psychological Capital: An Evidence-Based Positive Approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhanuddin, N.A.N.; Ahmad, N.A.; Said, R.R.; Asimiran, S. A Systematic Review of the Psychological Capital (PsyCap) Research Development: Implementation and Gaps. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 2019, 8, 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cimen, I.; Ozgan, H. Contributing and damaging factors related to the psychological capital of teachers: A qualitative analysis. Issues Educ. Res. 2018, 28, 308–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W.M.; Rhee, S.Y.; Ahn, K.H. Positive psychological capital and emotional labor in Korea: The job demands-resources approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lian, X. Psychological Capital, Emotional Labor and Counterproductive Work Behavior of Service Employees: The Moderating Role of Leaders’ Emotional Intelligence. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2015, 5, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamer, I. The Effect Of Positive Psychological Capital on Emotional Labor. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D.; King, R.B.; Valdez, J.P.M.; Alfonso, J.; King, R.B.; Valdez, J.P.M. Psychological capital bolsters motivation, engagement, and achievement: Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 13, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, O.L.; Bakker, A.B.; Jiang, X. Psychological Capital among University Students: Relationships with Study Engagement and Intrinsic Motivation. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 979–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueb, R.; Hashim, H.; Said Hashim, K.; Mohd Izam, M. Excellent Teachers’ Strategies in Managing Students’ Misbehaviour in the Classroom. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2020, 16, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fred, A.; Bishen, S.; Gurcharan, S. Instructional Leadership Practices in Under-Enrolled Rural Schools in Miri, Sarawak. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2021, 17, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefai, C.; Cavioni, V. Social and Emotional Education in Primary School: Integrating Theory and Research into Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital and Beyond; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, Social, and Now Positive Psychological Capital Management: Investing in People for Competitive Advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. The Need for and Meaning of Positive Organizational Behaviour. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Li, W. The psychological capital of Chinese workers: Exploring the relationship with performance. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Norman, S.M.; Combs, G.M. Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Hobfoll, S.E. Work Can Burn Us Out or Fire Us up: Conservation of Resources in Burnout and Engagement. In Handbook of Stress and Burnout in Health Care; Nova Science: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ganotice, F.A., Jr.; Yeung, S.S.; Beguina, L.A. In Search for H.E.R.O Among Filipino Teachers: The Relationship of Positive Psychological Capital and Work-Related Outcomes. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2015, 25, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S. Teachers as Leaders: The Role of Psychological Capital on the Work Engagement. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H.; Chen, Y.T.; Hsu, M.H. A Case Study on Psychological Capital and Teaching Effectiveness in Elementary Schools. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2014, 6, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yalcin, S. Analyzing the Relationship between Positive Psychological Capital and Organizational Commitment of the Teachers. Int. Educ. Stud. 2016, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsing-Ming, L.; Mei-Ju, C.; Chia-Hui, C.; Ho-Tang, W. The Relationship between Psychological Capital and Professional Commitment of Preschool Teachers: The Moderating Role of Working Years. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 5, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty, M. The Foundations of Social Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H. On the Scope and Function of Hermeneutical Reflection 1967. In Hans-Georg Gadamer: Philosophical Hermeneutics; Linge, D.E., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkley, MA, USA, 1976; pp. 18–43. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time; Stambaugh, J., Translator; New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzel, A.J. Sampling in Qualitative Inquiry. In Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Crabtree, B.F., Miller, W.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. Phenomenological Research Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Eatough, V. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Research Methods in Psychology, 3rd ed.; Breakwell, G., Fife-Schaw, C., Hammond, S., Smith, J.A., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Langdridge, D. Phenomenological Psychology: Theory, Research and Method; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, C.; Palmgren, P.J.; Liljedahl, M. Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Qualitative Case Studies. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India, 2005; pp. 443–466. [Google Scholar]

- Agar, M. The Professional Stranger: An Informal Introduction to Ethnography; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Yardley, L. Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychol. Health 2000, 15, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Wernsing, T.S.; Mhatre, K.H. A longitudinal analysis of positive psychological constructs and emotions on stress, anxiety, and well-being. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2011, 18, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge; Oxford University Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A.; Buitendach, J.H.; Kanengoni, H. Psychological capital, subjective well-being, burnout and job satisfaction amongst educators in the Umlazi region in South Africa. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M. An Exploration of The Relationship between Psychological Capital (Hope, Optimism, Self-Efficacy, Resilience), Occupational Stress, Burnout and Employee Engagement. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, K.M. Are You a H.e.r.o.? A Mixed Methods Study of the Relationship between Illinois Principals’ Psychological Capital and School Culture. Ph.D. Thesis, Loyola University, Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, F.; Arizi, H.; Noori, A.; Namdari, K. The relationship between psychological capital in the workplace and employees’ passion for their work in the organization. Q. J. Occup. Organ. Couns. 2012, 4, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi, M.; Aghae, E.; Jamali, S.; Abedi, A. Meta-analysis of comparing the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment and psychological interventions on the rate of depression symptoms. J. Cult. Couns. Psychother. 2012, 10, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudvand, M. Investigating the relationship between mental health and depression among third grade secondary school female students in Zahedan area. In Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Tabriz, Iran, 17 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alipoor, A.; Saffarinia, M.; Forushani, G.H.; Aghaalikhani, A.M.; Akhoondi, N. Investigating the effectiveness of Luthans’ psychological capital intervention on burnout of experts working in Iran Khodro Diesel Company. Q. J. Med. 2013, 4, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.-j. Research on a PCI model-based reform in college students’ entrepreneurship education. In Proceedings of the 2011 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Management Science and Electronic Commerce (AIMSEC), Dengfeng, China, 8–10 August 2011; pp. 1361–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, L.T. Juggling Demands: The Impact of Middle Manager Roles and Psychological Capital. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Taris, T.W. Work engagement: An Emerging Concept in Occupational Health Psychology. Work Stress. 2008, 22, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafei, W. The Effects of Psychological Capital on Employee Attitudes and Employee Performance: A Study on Teaching Hospitals in Egypt. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. Instructional Coaching: A Partnership Approach to Improving Instruction; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; Available online: http://site.ebrary.com/id/10333453 (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Loehr, J.S.; Schwartz, T. The Power of Full Engagement: Managing Energy, Not Time, Is the Key to High Performance and Personal Renewal; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz, R.A.; Linsky, M. Leadership on the Line: Staying Alive Through the Dangers of Leading; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; Available online: https://books.google.ca/books?id=c3mYE7jNvn0C (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Knight, J. Instructional Coaching. Sch. Adm. 2006, 63, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. Leading in a Culture of Change; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F. The High Impact Leader: Moments Matter in Accelerating Authentic Leadership Development; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J. Authentic leadership: A positive developmental approach. In Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Barrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Norman, S.M.; Hughes, L. Authentic leadership. In Inspiring Leaders; Burke, R., Cooper, C., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2006; pp. 84–204. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, S.M.; Luthans, F. Relationship between entrepreneurs’ psychological capital and their authentic leadership. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 254–273. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Peterson, S.J.; Avolio, B.J.; Hartnell, C.A. Relationships of leader and follower psychological capital, service climate, and job performance. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 937–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Learned Optimism; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, K. Educator’s Positive Stress Responses: Eustress and Psychological Capital. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, DePaul University, Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Badran, M.A.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Psychological capital and job satisfaction in Egypt. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive Psychological Capital: Measurement and Relationship with Performance and Satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Reichard, R.J.; Luthans, F.; Mhatre, K.H. Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Positive Psychological Capital on Employee Attitudes, Behaviours, and Performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slåtten, T.; Lien, G.; Marie, C.; Horn, F.; Pedersen, E. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence The links between psychological capital, social capital, and work-related performance-A study of service sales representatives. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 3363, S195–S209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B. The role of cognitive development in Mezirow’s transformational learning theory. Adult Educ. Q. 2004, 55, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCompte, M.D.; Preissle, J. Ethnography and Qualitative Design in Educational Research, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Golparvar, M. Construct and Validation of Three-Dimensional Scale of Job Happiness. Unpublished Manuscript. Islamic Azad University: Esfahan, Iran, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F. Positive organizational behaviour: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2002, 16, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pseudonym | Age, Gender and Racial Background | Years Qualified as an Instructional IC | Previous Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Ahmad” | 59, M, Malay | 2014 | Lecturer |

| “Laila” | 57, F, Malay | 2014 | Lecturer |

| “Siti” | 55, F, Malay | 2014 | Excellent Teacher |

| “Zaiton” | 55, F, Malay | 2013 | Excellent Teacher |

| “Asyikin” | 52, F, Malay | 2014 | Excellent Teacher |

| “Sheila” | 49, F, Malay | 2014 | Lecturer |

| “Yahya” | 57, M, Malay | 2014 | Excellent Teacher |

| Prepare | Contact | Follow Up |

|---|---|---|

| Describing the sample: Exemplary ICs, were an instructional coach for 5 years or more, highest grade for a government officer | Initial approach: Access and ethical considerations acknowledged, all potential applicants contacted through WhatsApp to send notification of study | Feedback to and from participants: Reiteration of participant information provided |

| Finding information sources: Determine potential group for target sample | Negotiation with key contacts: Negotiation with School Management Division and Educational Planning and Research Division, State Education Department. Request for ethical permission from University Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects (JKEUPM) | Feedback from key contacts: Findings discussed with research team |

| Discovering recent or related projects: No other research studies involving target sample at time of study | Direct negotiations: Requests made for potential participants. Information sheet sent out to all ICs with assurance of anonymity/confidentiality | Continuing links: Agreement received from individual participants to provide face-to-face feedback |

| Super-Ordinate Themes | Sub-Ordinate Themes |

|---|---|

| A sense of responsibility | Responsibility to others Realising the skills and quality in self |

| Positive resources | Keeping a positive mind Positive attitude and behaviour |

| Work commitment | Having goals set in mind and working hard towards achieving those goals Knowledge-seeking behaviour Job as calling |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burhanuddin, N.A.N.; Ahmad, N.A.; Said, R.R.; Asimiran, S. The Alchemy of Coaching: Psychological Capital as HERO within Coaches’ Selves. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912020

Burhanuddin NAN, Ahmad NA, Said RR, Asimiran S. The Alchemy of Coaching: Psychological Capital as HERO within Coaches’ Selves. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912020

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurhanuddin, Nur Aimi Nasuha, Nor Aniza Ahmad, Rozita Radhiah Said, and Soaib Asimiran. 2022. "The Alchemy of Coaching: Psychological Capital as HERO within Coaches’ Selves" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912020