Metastasis-Free Survival in Patients with Biochemical Recurrence After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study in Japan (MSUG94 Group)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Preoperative Clinical Variables

2.2. Surgical and Pathological Variables

2.3. Follow-Up Protocol

2.4. Endpoints and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients and Characteristics

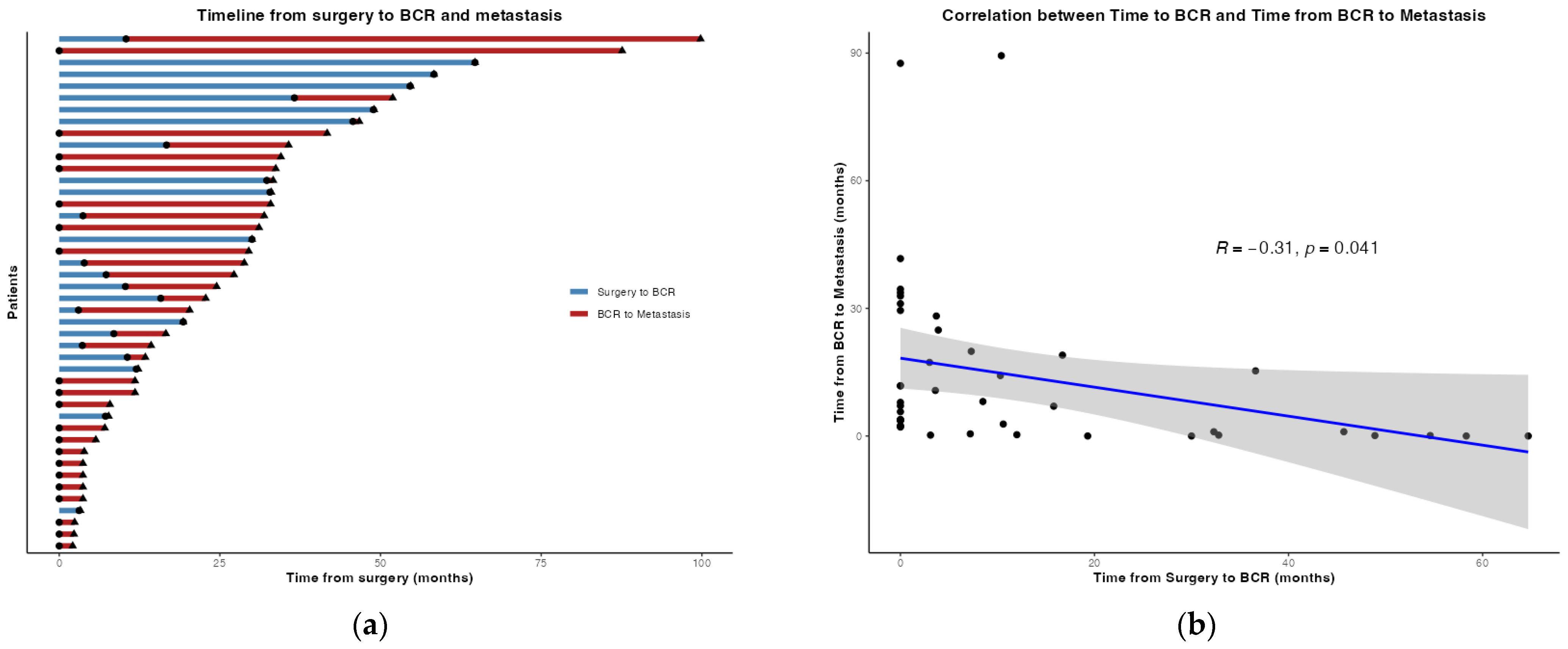

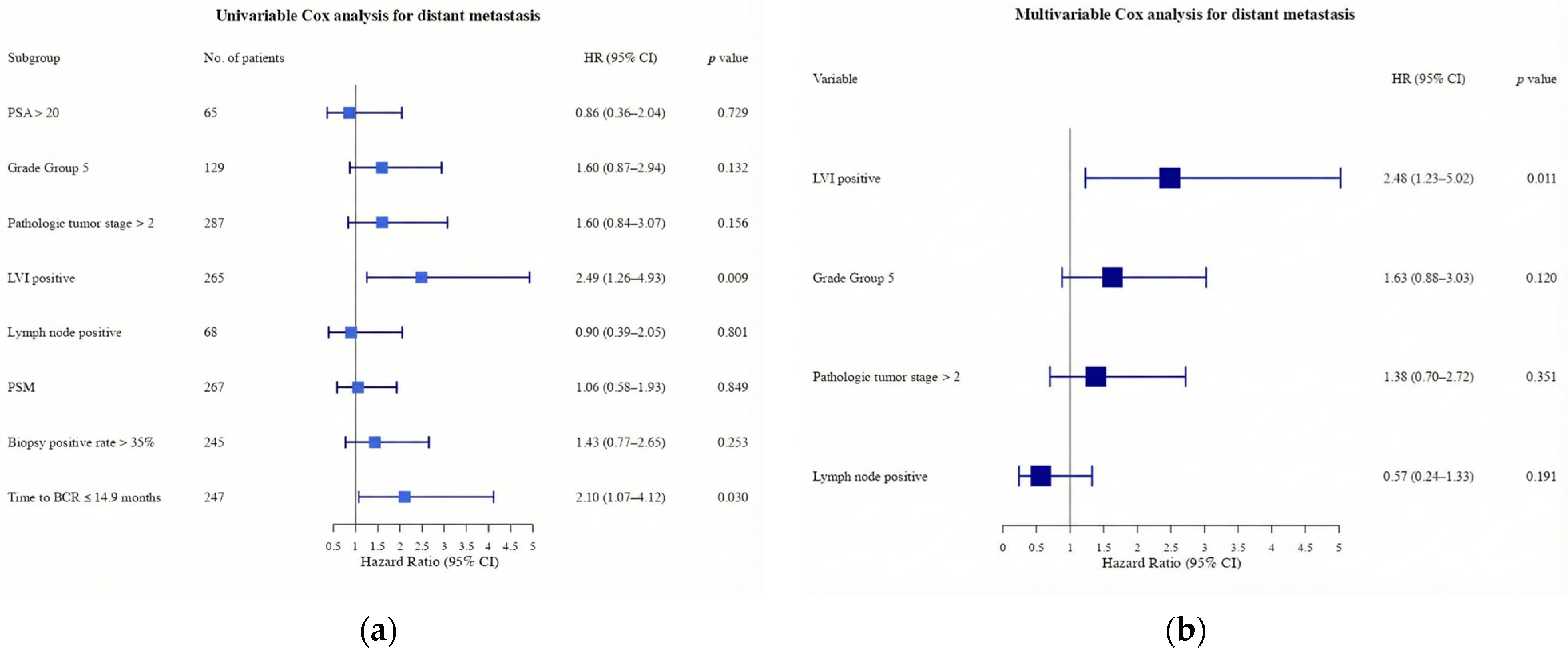

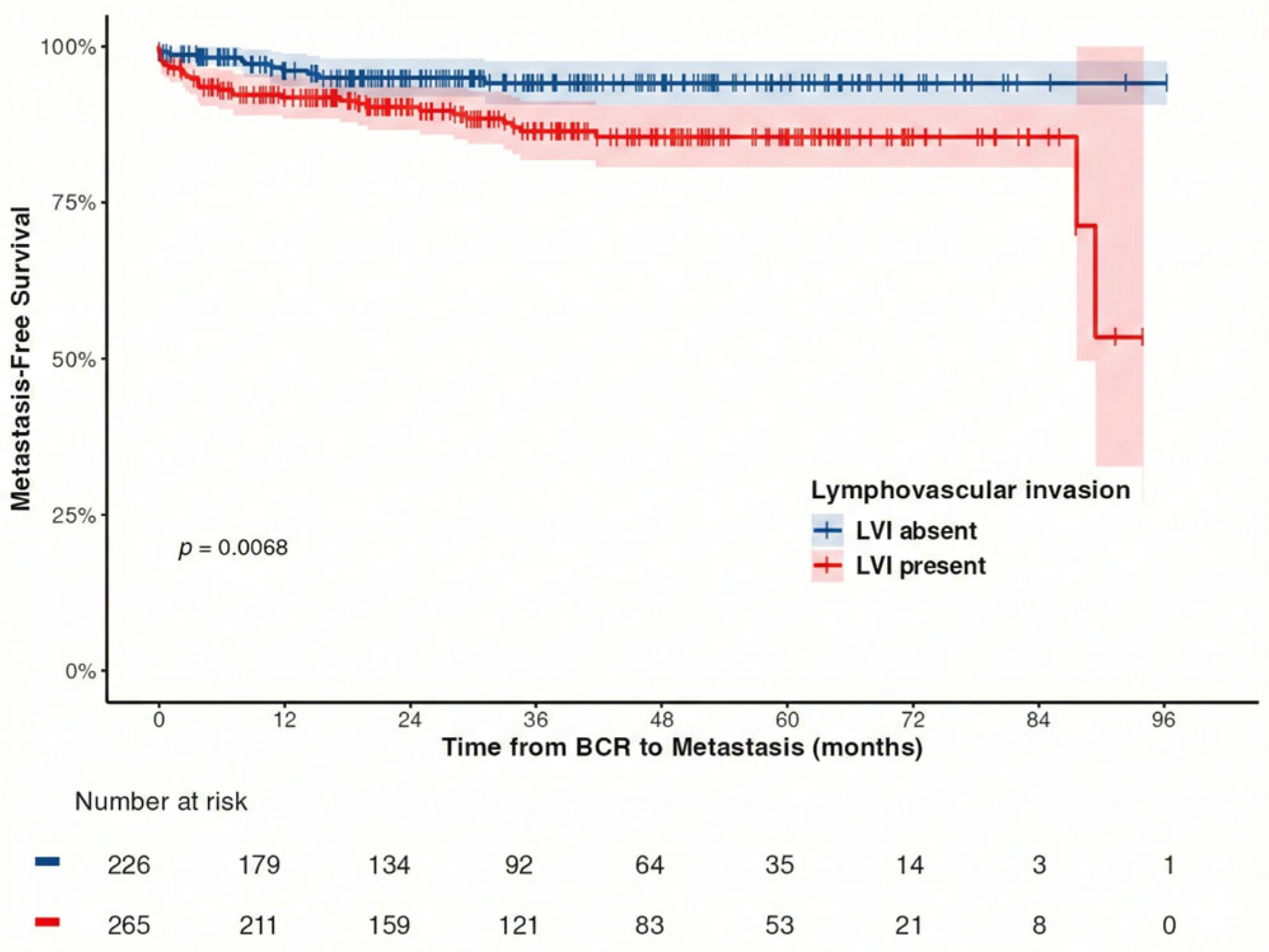

3.2. Metastasis-Free Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boorjian, S.A.; Thompson, R.H.; Tollefson, M.K.; Rangel, L.J.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Blute, M.L.; Karnes, R.J. Long-term risk of clinical progression after biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy: The impact of time from surgery to recurrence. Eur. Urol. 2011, 59, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Feng, Z.; Trock, B.J.; Humphreys, E.B.; Carducci, M.A.; Partin, A.W.; Walsh, P.C.; Eisenberger, M.A. The natural history of metastatic progression in men with prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy: Long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2012, 109, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, D.; Ebara, S.; Tatenuma, T.; Sasaki, T.; Ikehata, Y.; Nakayama, A.; Toide, M.; Yoneda, T.; Sakaguchi, K.; Teishima, J.; et al. Short-term oncological and surgical outcomes of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: A retrospective multicenter cohort study in Japan (the MSUG94 group). Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2022, 15, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pound, C.R.; Partin, A.W.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Chan, D.W.; Pearson, J.D.; Walsh, P.C. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA 1999, 281, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedland, S.J.; Humphreys, E.B.; Mangold, L.A.; Eisenberger, M.; Dorey, F.J.; Walsh, P.C.; Partin, A.W. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA 2005, 294, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzman, D.L.; Zhou, X.C.; Zahurak, M.L.; Lin, J.; Antonarakis, E.S. Change in PSA velocity is a predictor of overall survival in men with biochemically-recurrent prostate cancer treated with nonhormonal agents: Combined analysis of four phase-2 trials. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2015, 18, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, M.T.; Zhou, X.C.; Wang, H.; Yang, T.; Shaukat, F.; Partin, A.W.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Antonarakis, E.S. Metastasis-free survival is associated with overall survival in men with PSA-recurrent prostate cancer treated with deferred androgen deprivation therapy. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2881–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prostate Cancer (2026) NCCN Guidelines®. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Epstein, J.I.; Egevad, L.; Amin, M.B.; Delahunt, B.; Srigley, J.; Humphrey, P.A.; Committee, G. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: Definition of Grading Patterns and Proposal for a New Grading System. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.; Parekh, D.J.; Cookson, M.S.; Chang, S.S.; Smith, E.R., Jr.; Wells, N.; Smith, J.A., Jr. Randomized prospective evaluation of extended versus limited lymph node dissection in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furubayashi, N.; Negishi, T.; Iwai, H.; Nagase, K.; Taguchi, K.; Shimokawa, M.; Nakamura, M. Determination of adequate pelvic lymph node dissection range for Japanese males undergoing radical prostatectomy. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyyounouski, M.K.; Choyke, P.L.; McKenney, J.K.; Sartor, O.; Sandler, H.M.; Amin, M.B.; Kattan, M.W.; Lin, D.W. Prostate cancer—Major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, M.S.; Aus, G.; Burnett, A.L.; Canby-Hagino, E.D.; D’Amico, A.V.; Dmochowski, R.R.; Eton, D.T.; Forman, J.D.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Hernandez, J.; et al. Variation in the definition of biochemical recurrence in patients treated for localized prostate cancer: The American Urological Association Prostate Guidelines for Localized Prostate Cancer Update Panel report and recommendations for a standard in the reporting of surgical outcomes. J. Urol. 2007, 177, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, S.; You, D.; Jeong, I.G.; Kim, Y.S.; Hong, J.H.; Kim, C.S.; Ahn, H. Time to biochemical relapse after radical prostatectomy and efficacy of salvage radiotherapy in patients with prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 24, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axén, E.; Stranne, J.; Månsson, M.; Holmberg, E.; Arnsrud Godtman, R. Biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy—A large, comprehensive, population-based study with long follow-up. Scand. J. Urol. 2022, 56, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, D.M.; Ta, A.; Bagnato, M.; Muller, D.; Lawrentschuk, N.L.; Severi, G.; Syme, R.R.; Giles, G.G. Interval to biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy does not affect survival in men with low-risk prostate cancer. World J. Urol. 2014, 32, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedland, S.J.; Humphreys, E.B.; Mangold, L.A.; Eisenberger, M.; Partin, A.W. Time to prostate specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy and risk of prostate cancer specific mortality. J. Urol. 2006, 176, 1404–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Chen, Y.; Elsamanoudi, S.I.; Brassell, S.A.; Da Rocha, M.V.; Eisenberger, M.A.; McLeod, D.G. Long-term overall survival and metastasis-free survival for men with prostate-specific antigen-recurrent prostate cancer after prostatectomy: Analysis of the Center for Prostate Disease Research National Database. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Koo, K.C.; Lee, K.S.; Hah, Y.S.; Rha, K.H.; Hong, S.J.; Chung, B.H. Time to disease recurrence is a predictor of metastasis and mortality in patients with high-risk prostate cancer who achieved undetectable prostate-specific antigen following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2018, 33, e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schisterman, E.F.; Cole, S.R.; Platt, R.W. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 2009, 20, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, J.A.; Alanee, S.; Vickers, A.J.; Scardino, P.T.; Wood, D.P.; Kibel, A.S.; Lin, D.W.; Bianco, F.J.; Rabah, D.M.; Klein, E.A.; et al. Nomogram predicting prostate cancer-specific mortality for men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompe, R.S.; Gild, P.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Bock, L.-P.; Schlomm, T.; Steuber, T.; Graefen, M.; Huland, H.; Tian, Z.; Tilki, D. Long-term cancer control outcomes in patients with biochemical recurrence and the impact of time from radical prostatectomy to biochemical recurrence. Prostate 2018, 78, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, J.W.; Steigler, A.; Wilcox, C.; Lamb, D.S.; Joseph, D.; Atkinson, C.; Matthews, J.; Tai, K.H.; Spry, N.A.; Christie, D.; et al. Time to biochemical failure and prostate-specific antigen doubling time as surrogates for prostate cancer-specific mortality: Evidence from the TROG 96.01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, H.; Yan, L.; Ye, T.; Lu, H.; Sun, X.; Ye, Z.; Xu, H. Prognostic significance of six clinicopathological features for biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 32238–32249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesen, A.; Milonas, D.; Laenen, A.; Tosco, L.; Chlosta, P.; De Meerleer, G.; Devos, G.; Moris, L.; Claessens, F.; Albersen, M.; et al. Prognostic stratification of pN1 prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: A competing risk analysis from a multi-institutional cohort. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2025, 79, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barletta, F.; Tappero, S.; Morra, S.; Incesu, R.B.; Cano Garcia, C.; Piccinelli, M.L.; Scheipner, L.; Tian, Z.; Saad, F.; Graefen, M.; et al. Identification of patients with low cancer-specific mortality risk lymph node-positive radical prostatectomy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 129, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisser, F.; Marchioni, M.; Nazzani, S.; Bandini, M.; Tian, Z.; Pompe, R.S.; Montorsi, F.; Graefen, M.; Shariat, S.F.; Saad, F.; et al. The impact of lymph node metastases burden at radical prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2019, 5, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschini, M.; Sharma, V.; Zattoni, F.; Quevedo, J.F.; Davis, B.J.; Kwon, E.; Karnes, R.J. Natural history of clinical recurrence patterns of lymph node-positive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touijer, K.A.; Karnes, R.J.; Passoni, N.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Assel, M.; Fossati, N.; Gandaglia, G.; Eastham, J.A.; Scardino, P.T.; Briganti, A. Survival outcomes of men with lymph node-positive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: A comparative analysis of different postoperative management strategies. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, M.C.; Burkhard, F.C.; Thalmann, G.N.; Fleischmann, A.; Studer, U.E. Good outcome for patients with few lymph node metastases after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 2008, 54, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedland, S.J.; de Almeida Luz, M.; De Giorgi, U.; Gleave, M.; Gotto, G.T.; Pieczonka, C.M.; Haas, G.P.; Stylianou, F.; McVary, K.T.; Freedland, R.L.; et al. Improved Outcomes with Enzalutamide in Biochemically Recurrent Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, Y.; Gupta, A.; Shariat, S.F.; Palapattu, G.S.; Vazina, A.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Bastian, P.J.; Rogers, C.G.; Amiel, G.; Perotte, P.; et al. Lymphovascular invasion is independently associated with overall survival, cause-specific survival, and local and distant recurrence in patients with negative lymph nodes at radical cystectomy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6533–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okiror, L.; Harling, L.; Toufektzian, L.; King, J.; Routledge, T.; Harrison-Phipps, K.; Pilling, J.; Veres, L.; Lal, R.; Bille, A. Prognostic factors including lymphovascular invasion on survival for resected non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 156, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G.; Annicchiarico, A.; Morini, A.; Pagliai, L.; Crafa, P.; Leonardi, F.; Dell’Abate, P.; Costi, R. Three distinct outcomes in patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma and lymphovascular invasion: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2671–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.C.; Winter, D.C.; Heeney, A.; Gibbons, D.; Lugli, A.; Puppa, G.; Sheahan, K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of tumour budding in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukagai, T.; Namiki, T.S.; Carlile, R.G.; Yoshida, H.; Namiki, M. Comparison of the clinical outcome after hormonal therapy for prostate cancer between Japanese and Caucasian men. BJU Int. 2006, 97, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperberg, M.R.; Hinotsu, S.; Namiki, M.; Carroll, P.R.; Akaza, H. Trans-Pacific variation in outcomes for men treated with primary androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2016, 117, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, B.; Muralidhar, V.; Chen, Y.-H.; Sridhar, S.S.; Mitchell, E.P.; Pettaway, C.A.; Carducci, M.A.; Nguyen, P.L.; Sweeney, C.J. Impact of ethnicity on the outcome of men with metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Cancer 2017, 123, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xu, C.; Lee, H.J.; Ren, S.; Zi, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Yang, C.; Gao, X.; et al. Genomic and epigenomic atlas of prostate cancer in Asian populations. Nature 2020, 580, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Non-Metastasis Group N = 447 | Metastasis Group N = 44 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, median, IQR) | 68.0 (64.0, 72.0) | 68.5 (61.5, 70.5) | 0.584 |

| BMI (kg/m2, median, IQR) | 23.8 (22.1, 25.8) | 24.1 (21.9, 26.0) | 0.767 |

| Initial PSA (ng/mL, median, IQR) | 9.8 (6.8, 15.3) | 10.6 (6.3, 15.9) | 0.986 |

| Biopsy Grade Group (number, %) | 0.002 | ||

| 1 | 37 (8.3) | 2 (4.5) | |

| 2 | 83 (18.6) | 2 (4.5) | |

| 3 | 114 (25.5) | 9 (20.5) | |

| 4 | 147 (32.9) | 14 (31.8) | |

| 5 | 66 (14.8) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Positive core rate (%, median, IQR) | 33 (22, 50) | 41 (25, 60) | 0.105 |

| Clinical T stage (number, %) | 0.210 | ||

| 1 | 46 (10.3) | 5 (11.4) | |

| 2 | 316 (70.7) | 26 (59.1) | |

| 3 | 85 (19.0) | 13 (29.5) | |

| NCCN risk classification (number, %) | 0.009 | ||

| Low | 9 (2.0) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Favorable intermediate | 43 (9.6) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Unfavorable intermediate | 134 (30.0) | 10 (22.7) | |

| High | 186 (41.6) | 15 (34.1) | |

| Very high | 72 (16.1) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Lymph node dissection (number, %) | 0.862 | ||

| None | 77 (17.2) | 9 (20.5) | |

| Limited | 211 (47.2) | 19 (43.2) | |

| Standard | 41 (9.2) | 3 (6.8) | |

| Extended | 118 (26.4) | 13 (29.5) | |

| Nerve-sparing (number, %) | >0.999 | ||

| None | 336 (75.2) | 34 (77.2) | |

| Unilateral | 92 (20.4) | 9 (20.5) | |

| Bilateral | 19 (4.33) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Pathological grade group (number, %) | 0.186 | ||

| 1 | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 95 (21.3) | 4 (9.1) | |

| 3 | 154 (34.5) | 16 (36.4) | |

| 4 | 81 (18.1) | 7 (15.9) | |

| 5 | 112 (25.1) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Pathological T stage (number, %) | 0.028 | ||

| 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (2.3) | |

| 2 | 190 (42.5) | 12 (27.3) | |

| 3 | 140 (31.3) | 12 (27.3) | |

| 4 | 116 (26.0) | 19 (43.2) | |

| Lymph node positive (number, %) | 61 (13.6) | 7 (15.9) | 0.678 |

| Positive surgical margin (number, %) | 242 (54.1) | 25 (56.8) | 0.733 |

| Lymphovascular invasion (number, %) | 232 (51.9) | 33 (75.0) | 0.003 |

| Adjuvant therapy (number, %) | 0.103 | ||

| None | 397 (88.8) | 37 (84.1) | |

| Radiotherapy | 17 (3.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Hormone therapy | 24 (5.4) | 5 (11.4) | |

| Both radiotherapy and hormone therapy | 9 (2.0) | 2 (4.5) | |

| Time from RARP to BCR (months, median, IQR) | 16 (5, 33) | 3 (0, 16) | <0.001 |

| Salvage radiotherapy (number, %) | 181 (40.5) | 12 (27.3) | 0.087 |

| Salvage hormone therapy (number, %) | 194 (43.4) | 24 (54.5) | 0.156 |

| Metastasis time (months, median, IQR) | 24 (7, 34) | ||

| CRPC (number, %) | 7 (1.6) | 19 (43.2) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up period (months, median, IQR) | 59 (43, 73) | 57 (40, 71) | 0.605 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nezasa, M.; Tomioka, M.; Tatenuma, T.; Sasaki, T.; Ikehata, Y.; Nakayama, A.; Toide, M.; Yoneda, T.; Sakaguchi, K.; Makiyama, K.; et al. Metastasis-Free Survival in Patients with Biochemical Recurrence After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study in Japan (MSUG94 Group). Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010056

Nezasa M, Tomioka M, Tatenuma T, Sasaki T, Ikehata Y, Nakayama A, Toide M, Yoneda T, Sakaguchi K, Makiyama K, et al. Metastasis-Free Survival in Patients with Biochemical Recurrence After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study in Japan (MSUG94 Group). Current Oncology. 2026; 33(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleNezasa, Minori, Masayuki Tomioka, Tomoyuki Tatenuma, Takeshi Sasaki, Yoshinori Ikehata, Akinori Nakayama, Masahiro Toide, Tatsuaki Yoneda, Kazushige Sakaguchi, Kazuhide Makiyama, and et al. 2026. "Metastasis-Free Survival in Patients with Biochemical Recurrence After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study in Japan (MSUG94 Group)" Current Oncology 33, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010056

APA StyleNezasa, M., Tomioka, M., Tatenuma, T., Sasaki, T., Ikehata, Y., Nakayama, A., Toide, M., Yoneda, T., Sakaguchi, K., Makiyama, K., Inoue, T., Kitamura, H., Saito, K., Koga, F., Urakami, S., & Koie, T. (2026). Metastasis-Free Survival in Patients with Biochemical Recurrence After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study in Japan (MSUG94 Group). Current Oncology, 33(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010056