Comparison of Prophylactic Versus Reactive Tube Feeding Approaches on Weight Loss and Unplanned Hospital Admissions in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Receiving Chemoradiotherapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Clinical and Disease Characteristics

3.2. Patients’ Nutrition Characteristics

3.3. Weight Loss Outcomes

3.4. Unplanned Nutrition-Related Admissions

3.5. Unplanned Medical Admissions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell cancer |

| LOS | Length of stay |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary team |

| CRT | Chemoradiotherapy |

| H-IMRT | Helical intensity-modulated radiotherapy |

| PGSGA | Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment |

| SGA | Subjective Global Assessment |

| HD | High dose |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| NGT | Nasogastric tube |

| HPV | Human papilloma virus |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trial |

| CTCAE | Common toxicity criteria for adverse events |

| QOL | Quality of life |

| GRADE | Grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation |

References

- Ackerman, D.; Laszlo, M.; Provisor, A.; Yu, A. Nutrition Management for the Head and Neck Cancer Patient. Cancer Treat. Res. 2018, 174, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossola, M. Nutritional interventions in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy: A narrative review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orell, H.; Schwab, U.; Saarilahti, K.; Osterlund, P.; Ravasco, P.; Makitie, A. Nutritional Counseling for Head and Neck Cancer Patients Undergoing (Chemo) Radiotherapy—A Prospective Randomized Trial. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powrózek, T.; Dziwota, J.; Małecka-Massalska, T. Nutritional Deficiencies in Radiotherapy-Treated Head and Neck Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, M.; Bauer, J.; Brown, T.; Davidson, W.; Isenring, E.; Kiss, N.; Kurmis, R.; Loeliger, J.; Sandison, A.; Talwar, B.; et al. Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines for the Nutritional Management of Adult Patients with Head and Neck Cancer; Cancer Council Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2011; Available online: https://app.magicapp.org/#/guideline/Eez3Kj (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Homer, J.J.; Winter, S.; Abbey, E.; Aga, H.; Agrawal, R.; Ap Dafydd, D.; Arunjit, T.; Axon, P.; Aynsley, E.; Bagwan, I.; et al. Head and Neck Cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines, Sixth Edition. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2024, 138, S1–S224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hutterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, B.; Baker, A.; Wolfenden, L.; Wratten, C.; Bauer, J.; Beck, A.; McCarter, K.; Handley, T.; Carter, G. Five-Year Mortality Outcomes for Eating As Treatment (EAT), a Health Behavior Change Intervention to Improve Nutrition in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer: A Stepped-Wedge, Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 119, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar-Mangaj, S.; Laskar, S.G.; Talapatra, K. Choosing Optimal Feeding Method in Head–Neck Cancer Patients Receiving Radiation: Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Versus Nasogastric Tube—Is It Pertinent? J. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 6, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

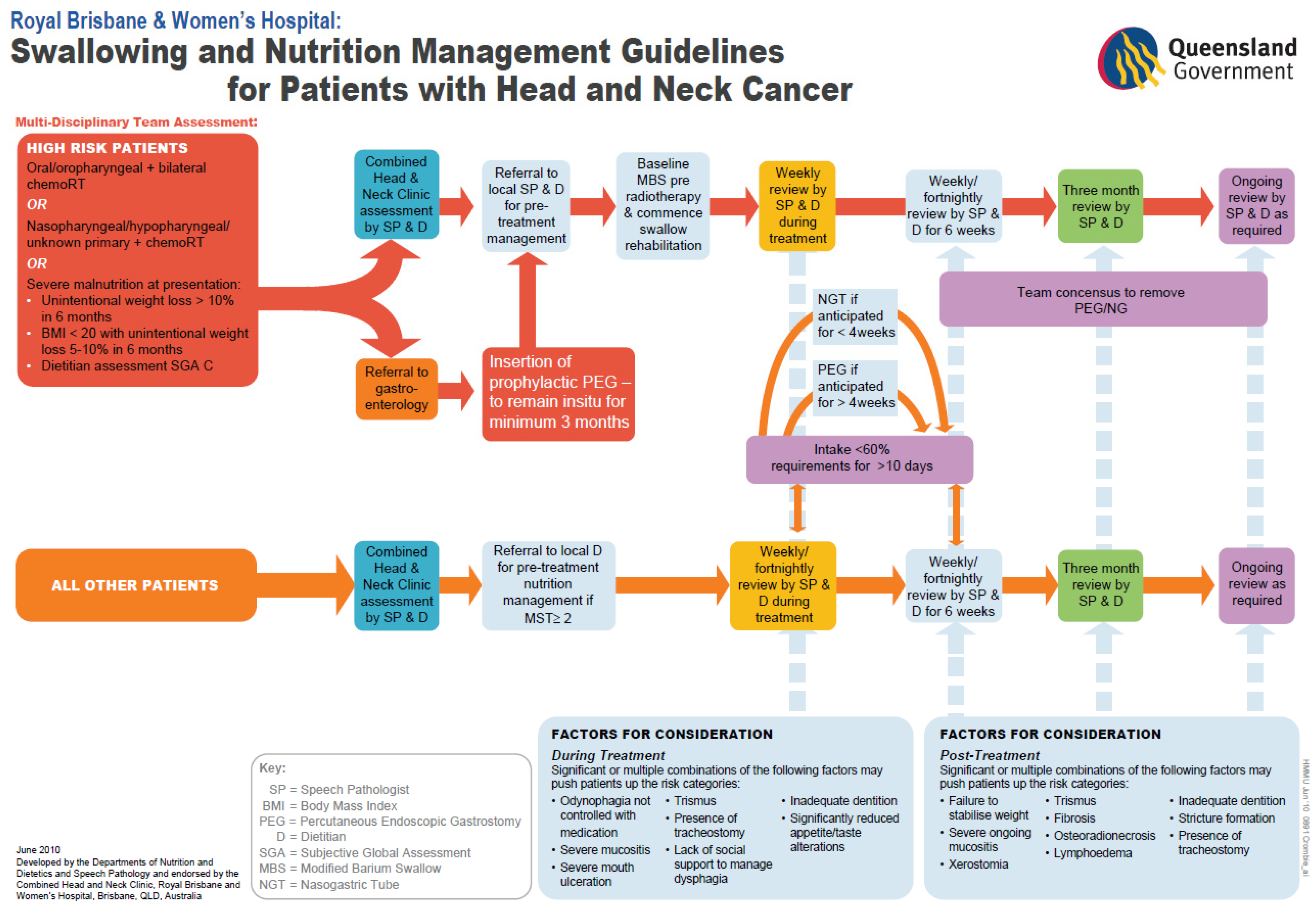

- Brown, T.E.; Spurgin, A.; Ross, L.; Tripcony, L.; Keller, J.; Hughes, B.; Hodge, R.; Walker, Q.; Banks, M.; Kenny, L.; et al. Validated swallowing and nutrition guidelines for patients with head and neck cancer: Identification of high-risk patients for proactive gastrostomy. Head Neck 2013, 35, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Ottery, F.D. Assessing nutritional status in cancer: Role of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 4.5.0; R. Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Malone, A.; Hamilton, C. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition consensus malnutrition characteristics: Application in practice. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2013, 28, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langius, J.A.; Twisk, J.; Kampman, M.; Doornaert, P.; Kramer, M.; Weijs, P.; Leemans, C. Prediction model to predict critical weight loss in patients with head and neck cancer during (chemo)radiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2016, 52, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Dijkstra, P.; Vissink, A.; van der Laan, B.; van Oort, R.; Roodenburg, J. Critical weight loss in head and neck cancer—Prevalence and risk factors at diagnosis: An explorative study. Support. Care Cancer 2007, 15, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Senesse, P.; Gioulbasabis, I.; Antoun, S.; Bozzetti, F.; Deans, C.; Strasser, F.; Thoresen, L.; Jagoe, R.; Chasen, M.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for the classification of cancer-associated weight loss. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langius, J.A.; Bakker, S.; Rietveld, D.; Kruizenga, H.; Langendijk, J.; Weijs, P.; Leemans, C. Critical weight loss is a major prognostic indicator for disease-specific survival in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.; Karam, I.; Wilson, G.; Bowman, A.; Lee, C.; Wong, F. Population-based comparison of two feeding tube approaches for head and neck cancer patients receiving concurrent systemic-radiation therapy: Is a prophylactic feeding tube approach harmful or helpful? Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 3433–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClelland, S.; Andrews, J.; Chaudhry, H.; Teckie, S.; Goenka, A. Prophylactic versus reactive gastrostomy tube placement in advanced head and neck cancer treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy: A systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2018, 87, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellors, K.; Ye, X.; van den Brande, J.; Wai Ray Mak, T.; Brown, T.; Findlay, M.; Bauer, J. Comparison of prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with reactive enteral nutrition in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 46, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wan, H. Comparative effects of different enteral feeding methods in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy: A network meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 2897–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossola, M.; Antocicco, M.; Pepe, G. Tube feeding in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy: A systematic review. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2022, 46, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capoccia, D.; Milani, I.; Colangeli, L.; Parrotta, M.; Leonetti, F.; Guglielmi, V. Social, cultural and ethnic determinants of obesity: From pathogenesis to treatment. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choulli, M.; Morey, F.; Tous, S.; Brenes, J.; Wang, X.; Quiros, B.; Gonzalez-Tampan, A.; Pavon, M.; Goma, M.; Taberna, M.; et al. Exploring the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) status in body composition and nutritional features in patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 67, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.; Brown, T.; Hughes, B.; Bauer, J. The changing face of head and neck cancer: Are patients with human papillomavirus-positive disease at greater nutritional risk? A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7191–7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Ross, L.; Jones, L.; Hughes, B.; Banks, M. Nutrition outcomes following implementation of validated swallowing and nutrition guidelines for patients with head and neck cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 2381–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.E.; Banks, M.; Hughes, B.; Lin, C.; Kenny, L.; Bauer, J. Randomised controlled trial of early prophylactic feeding vs. standard care in patients with head and neck cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Banks, M.; Hughes, B.; Lin, C.; Kenny, L.; Bauer, J. Tube feeding during treatment for head and neck cancer—Adherence and patient reported barriers. Oral Oncol. 2017, 72, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, C.L.; Brown, T.; Pelecanos, A.; Moroney, L.; Helios, J.; Hughes, B.; Chua, B.; Kenny, L. Enteral nutrition support and treatment toxicities in patients with head and neck cancer receiving definitive or adjuvant helical intensity-modulated radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy. Head Neck 2023, 45, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.E.; Banks, M.; Hughes, B.; Lin, C.; Kenny, L.; Bauer, J. Comparison of Nutritional and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Undergoing Chemoradiotherapy Utilizing Prophylactic versus Reactive Nutrition Support Approaches. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddle, M.R.; Chen, R.; Arastu, N.; Green, R.; Jackson, M.; Qaqish, B.; Camporeale, J.; Collichio, F.; Marks, L. Unanticipated hospital admissions during or soon after radiation therapy: Incidence and predictive factors. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 5, e245–e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, D.C.; Kabolizadeh, P.; Heron, D.; Ohr, J.; Wang, H.; Johnson, J.; Kubicek, G. Incidence of hospitalization in patients with head and neck cancer treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Head Neck 2015, 37, 1750–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, E.; Brooker, R.; Fleming, J.; Patterson, J. A review of unplanned admissions in head and neck cancer patients undergoing oncological treatment. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, B.; Findlay, M. When is the optimal time for placing a gastrostomy in patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer? Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2012, 6, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.T.; Brown, T.; Paleri, V. Gastrostomy in head and neck cancer: Current literature, controversies and research. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 23, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, B.G.; Jain, V.; Brown, T.; Spurgin, A.; Hartnett, G.; Keller, J.; Tripcony, L.; Appleyard, M.; Hodge, R. Decreased hospital stay and significant cost savings after routine use of prophylactic gastrostomy for high-risk patients with head and neck cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy at a tertiary cancer institution. Head Neck 2013, 35, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, B.; Parker, M.J.; McIntyre, I.A. Nasogastric tube feeding and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding in patients with head and neck cancer. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 23, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baschnagel, A.M.; Yadav, S.; Marina, O.; Parzuchowski, A.; Lanni, T.; Warner, J.; Parzuchowski, J.; Ignatius, R.; Akervall, J.; Chen, P.; et al. Toxicities and costs of placing prophylactic and reactive percutaneous gastrostomy tubes in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancers treated with chemoradiotherapy. Head Neck 2014, 36, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapała, A.; Surwillo-Snarska, A.; Jodkiewicz, M.; Kawecki, A. Nutritional Care in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer during Chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and Bioradiotherapy (BRT) Provides Better Compliance with the Treatment Plan. Cancers 2021, 13, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.C.; Pandey, R.; Rajaretnam, M.; Delaibatiki, M.; Peel, D. Routine Prophylactic Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in Head and Neck Cancers with Bilateral Neck Irradiation: A Regional Cancer Experience in New Zealand. J. Med. Radiat. Sci. 2023, 70, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, C.E.; Yovino, S.; Taylor, R.; Wolf, J.; Cullen, K.; Ord, R.; Athas, M.; Zimrin, A.; Strome, S.; Suntharalingam, M. Impact of early percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement on nutritional status and hospitalization in patients with head and neck cancer receiving definitive chemoradiation therapy. Head Neck 2011, 33, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.M.; Li, B.; Lau, D.; Farwell, D.; Luu, Q.; Stuart, K.; Newman, K.; Purdy, J.; Vijayakumar, S. Evaluating the role of prophylactic gastrostomy tube placement prior to definitive chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 78, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaver, M.E.; Matheny, K.; Roberts, D.; Myers, J. Predictors of weight loss during radiation therapy. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2001, 125, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Machtay, M.; Unger, L.; Weinstein, G.; Weber, R.; Chalian, A.; Rosenthal, D. Prophylactic gastrostomy tubes in patients undergoing intensive irradiation for cancer of the head and neck. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998, 124, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquet, M.-A.; Ozsahin, M.; Larpin, I.; Zouhair, A.; Coti, P.; Monney, M.; Monnier, P.; Mirimanoff, R.-O.; Roulet, M. Early nutritional intervention in oropharyngeal cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Support. Care Cancer 2002, 10, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Yanamoto, S.; Takeda, D.; Saito, H.; Sato, H.; Asoda, S.; Adachi, M.; Yuasa, H.; Uzawa, N.; Krita, H. Tube feeding in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradio-/radio therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on the GRADE approach. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 2025, 37, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.M.; Flowers, H.; O’Sullivan, B.; Hope, A.; Liu, L.; Martino, R. The effect of prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement on swallowing and swallow-related outcomes in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Dysphagia 2015, 30, 152–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, C.; Ye, Y.; Huang, G. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding for patients with head and neck cancer: A systematic review. J. Radiat. Res. 2014, 55, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, B.; Lewis, S.; O’Sullivan, J.M. Enteral feeding methods for nutritional management in patients with head and neck cancers being treated with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, Cd007904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, S.; Baumstarck-Barrau, K.; Alfonsi, M.; Digue, L.; Bagarry, D.; Feham, N.; Bensadoun, R.; Pignon, T.; Loundon, A.; Deville, J.; et al. Impact of the prophylactic gastrostomy for unresectable squamous cell head and neck carcinomas treated with radio-chemotherapy on quality of life: Prospective randomized trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 93, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silander, E.; Nyman, J.; Bove, M.; Johansson, L.; Larsson, S.; Hammerlid, E. Impact of prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy on malnutrition and quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer: A randomized study. Head Neck 2012, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silander, E.; Jacobsson, I.; Berteus-Forslund, H.; Hammerlid, E. Energy intake and sources of nutritional support in patients with head and neck cancer—A randomised longitudinal study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsson, L.; Silander, E.; Nyman, J.; Bove, M.; Johansson, L.; Hammerlid, E. Effect of prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube on swallowing in advanced head and neck cancer: A randomized controlled study. Head Neck 2017, 39, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleri, V.; Patterson, J.; Rousseau, N.; Moloney, E.; Craig, D.; Tzelis, D.; Wilkinson, N.; Franks, J.; Hynes, A.; Heaven, B.; et al. Gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding for chemoradiation patients with head and neck cancer: The TUBE pilot RCT. Health Technol. Assess. 2018, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskar, S.G.; Sinha, S.; Jeeva, M.; Gupta, M.; Karmakar, S.; Kumar, A.; Mohanty, S.; Mahajan, P.; Timmanpyati, S.; Balaji, A.; et al. Prophylactic Versus Reactive (PvR) Feeding in Patients Undergoing (Chemo)radiation in Head and Neck Cancers: Results of a Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial. Head Neck 2025, 47, 3301–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corry, J.; Poon, W.; McPhee, N.; Milner, A.; Cruickshank, D.; Porceddu, S.; Rischin, D.; Peters, L. Randomized study of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tubes for enteral feeding in head and neck cancer patients treated with (chemo)radiation. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2008, 52, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramyothin, P.; Manyanont, S.; Trakarnsanga, A.; Petsuksiri, J.; Ithimakin, S. A prospective study comparing prophylactic gastrostomy to nutritional counselling with a therapeutic feeding tube if required in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy in Thai real-world practice. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croake, D.J.; Angadi, V. Prophylactic Versus Reactive Gastrostomy Tubes in Head and Neck Cancer: Making Joint Decisions. Perspect. ASHA Spec. Interest Groups 2019, 4, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, G.; Mancin, S.; Matteucci, S.; Cattani, D.; Pastore, M.; Franzese, C.; Scorsetti, M.; Mazzoleni, B. Nutritional prehabilitation in head and neck cancer: A systematic review of literature. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 58, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, C.; Edwards, A.; Treleaven, E.; Brown, T.; Hughes, B.; Lin, C.; Kenny, L.; Banks, M.; Bauer, J. Evaluation of a novel pre-treatment model of nutrition care for patients with head and neck cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 79, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corry, J. Feeding tubes and dysphagia: Cause or effect in head and neck cancer patients. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 53, 431–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wopken, K.; Bijl, H.; Langendijk, J. Prognostic factors for tube feeding dependence after curative (chemo-) radiation in head and neck cancer: A systematic review of literature. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 126, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crombie, J.; Ng, S.; Spurgin, A.-L.; Ward, E.; Brown, T.; Hughes, B. Swallowing outcomes and PEG dependence in head and neck cancer patients receiving definitive or adjuvant radiotherapy +/− chemotherapy with a proactive PEG: A prospective study with long term follow up. Oral Oncol. 2015, 51, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Banks, M.; Hughes, B.; Lin, C.; Kenny, L.; Buaer, J. Impact of early prophylactic feeding on long term tube dependency outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2017, 72, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Site A—Prophylactic Model of Care | Site B—Reactive Model of Care | |

|---|---|---|

| Criteria for proactive G tube insertion | Oral cavity or oropharyngeal cancer plus bilateral CRT or nasopharyngeal/hypopharyngeal/unknown primary plus CRT or those who were severely malnourished at presentation. | Individual cases for prophylactic tube placement were discussed at the multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting as per treating team discretion. |

| Criteria for reactive G tube insertion | Clinical decision making by the multidisciplinary team if oral intake was <60% of energy requirements, with inadequate intake and no expected improvement for a total of 10 days or more and duration of tube feeding anticipated to be >4 weeks. | Clinical decision making by the radiation oncologist following discussion with the multidisciplinary team at a case conference or multidisciplinary meeting and duration of tube feeding anticipated to be >4 weeks. |

| Criteria for reactive NGT insertion | Clinical decision making by the multidisciplinary team if oral intake was <60% of energy requirements, with inadequate intake and no expected improvement for a total of 10 days or more and duration of tube feeding anticipated to be <4 weeks. | Clinical decision making by the radiation oncologist following discussion with the multidisciplinary team at a case conference or multidisciplinary meeting and duration of tube feeding anticipated to be <4 weeks. |

| Primary method of G tube placement | Endoscopic placement | Radiological placement |

| Allied health management during treatment | Multidisciplinary allied health group education talk in week one of treatment, followed by weekly dietetic and speech pathology reviews during treatment. | Dietitian and speech pathology group education talk in week one of treatment, followed by weekly to fortnightly dietetic and speech pathology reviews during treatment, with frequency dependent upon nutrition impact symptoms. |

| Allied health management post treatment | Dietetic and speech pathology reviews for a minimum of six weeks post treatment, as clinically indicated. | Dietetic and speech pathology reviews for up to 6 weeks post treatment. |

| Characteristics | Site A n = 58 | Site B n= 30 | p-Value for Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (+/− SD) | 60 (+/− 9.6) | 59.6 (+/− 8.5) | 0.92 |

| Sex | Male % | 50 (86.2) | 27 (90) | 0.74 |

| Tumour Site (%) | 0.34 | |||

| Oral cavity | 8 (13.8) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| Oropharynx | 45 (77.6) | 24 (80) | ||

| Nasopharynx | 2 (3.4) | 2 (6.7) | ||

| Hypopharynx | 3 (5.2) | 3 (10) | ||

| Treatment (%) | 0.48 | |||

| CRT | 50 (86.2) | 28 (93.3) | ||

| Post op CRT | 8 (13.8) | 2 (6.7) | ||

| Radiotherapy Total Fraction | Mean (+/− SD) | 34.3 (+/− 1.7) | 34.6 (+/− 1.3) | 0.46 |

| Dose (Gy) | Mean (+/− SD) | 68.6 (+/− 3.4) | 69.3 (+/− 2.5) | 0.46 |

| Systemic Therapy (%) | 0.38 | |||

| HD cisplatin | 18 (31) | 14 (46.7) | ||

| Weekly cisplatin | 20 (38) | 6 (20.6) | ||

| Cetuximab | 18 (31) | 9 (30) | ||

| Other | 2 (3.4) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| T stage (%) | 0.82 | |||

| T0 | 2 (3.4) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| T1 | 10 (17.2) | 6 (20) | ||

| T2 | 20 (34.5) | 10 (33.3) | ||

| T3 | 10 (17.2) | 6 (20) | ||

| T4 | 16 (27.6) | 6 (20) | ||

| Recurrent | 0 (0) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| N Stage (%) | 0.85 | |||

| N0 | 3 (5.2) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| N1 | 6 (10.3) | 5 (16.7) | ||

| N2 | 47 (81) | 23 (76.7) | ||

| N3 | 2 (3.4) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| p16 Status | 0.56 | |||

| Positive | 36 (80) | 22 (91.7) | ||

| Negative | 6 (13.3) | 1 (4.2) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (6.7) | 1 (4.2) | ||

| Weight at start of CRT (kg) | 0.004 | |||

| Mean (+/− SD) | 82.4 (+/− 15.5) | 93.1 (+/− 17.4) | ||

| PG-SGA Category (%) | 1.00 | |||

| SGA A | 50 (86.2) | 24 (85.7) | ||

| SGA B | 7 (12.1) | 4 (14.3) | ||

| SGA C | 1 (1.7) | 0 (--) | ||

| PG-SGA Score at start CRT | ||||

| Mean (+/− SD) | 5 (+/− 3.9) | 6.5 (+/− 5.5) | 0.99 | |

| Type of Tube (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Nil | 17 (29.3) | 18 (60) | ||

| Proactive G tube | 36 (62.1) | 4 (13.3) | ||

| Reactive G tube | 1 (1.7) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| Reactive NGT | 4 (6.9) | 7 (23.3) | ||

| Weight Loss Outcome | Site A n (%) | Site B n (%) | p-Value for Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss ≥ 5% at the end of treatment | 32 (55) | 20 (67) | 0.417 |

| Weight loss ≥ 10% at the end of treatment | 8 (14) | 8 (27) | 0.155 |

| Weight loss ≥ 5% at 4–6 weeks post treatment | 16 (70) | 25 (86) | 0.182 |

| Weight loss ≥ 10% at 4–6 weeks post treatment | 11 (48) | 18 (62) | 0.456 |

| Weight Change | Site A Mean (+/− SD) Median (Range) | Site B Mean (+/− SD) Median (Range) | p-Value for Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| % weight change at the end of treatment | −6.1 (3.5) −5.6 (−14.2 to −0.8) | −7.2 (5.6) −7.7 (−19.4 to 2.3) | 0.350 |

| % weight change at 4–6 weeks post treatment | −9.6 (5.6) −7.9 (−21.8 to −2.5) | −11.7 (6.4) −11.9 (−23.3 to 1) | 0.150 |

| Unplanned Admissions in Each Cohort * | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reason for Admission | Site A (n = 19/58) | Site B (n = 7/30) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 36% (n = 7/19) | 29% (n = 2/7) |

| Odynophagia | 26% (n = 5/19) | 29% (n = 2/7) |

| Dehydration | 16% (n = 3/19) | 29% (n = 2/7) |

| Poor oral intake | 16% (n = 3/19) | 14% (n = 1/7) |

| Problems with tube feeding | 5% (n = 1/19) | 0% (n = 0/7) |

| Term | Estimate | SE | t | P | OR | OR 95% CI Lower | OR 95%CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 8.908 | 5.255 | 1.695 | 0.090 | - | - | - |

| Age | 0.060 | 0.030 | 2.041 | 0.041 | 1.062 | 1.002 | 1.125 |

| Radiation dose | −0.200 | 0.081 | 2.465 | 0.014 | 0.819 | 0.698 | 0.960 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brown, T.; Cooney, L.; Smith, D.; Elvin-Walsh, L.; Kern, E.; Ahern, S.; Brown, B.; Hickman, I.; Porceddu, S.; Kenny, L.; et al. Comparison of Prophylactic Versus Reactive Tube Feeding Approaches on Weight Loss and Unplanned Hospital Admissions in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Receiving Chemoradiotherapy. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010005

Brown T, Cooney L, Smith D, Elvin-Walsh L, Kern E, Ahern S, Brown B, Hickman I, Porceddu S, Kenny L, et al. Comparison of Prophylactic Versus Reactive Tube Feeding Approaches on Weight Loss and Unplanned Hospital Admissions in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Receiving Chemoradiotherapy. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Teresa, Louise Cooney, David Smith, Louise Elvin-Walsh, Eliza Kern, Suzanne Ahern, Bena Brown, Ingrid Hickman, Sandro Porceddu, Lizbeth Kenny, and et al. 2026. "Comparison of Prophylactic Versus Reactive Tube Feeding Approaches on Weight Loss and Unplanned Hospital Admissions in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Receiving Chemoradiotherapy" Current Oncology 33, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010005

APA StyleBrown, T., Cooney, L., Smith, D., Elvin-Walsh, L., Kern, E., Ahern, S., Brown, B., Hickman, I., Porceddu, S., Kenny, L., & Hughes, B. (2026). Comparison of Prophylactic Versus Reactive Tube Feeding Approaches on Weight Loss and Unplanned Hospital Admissions in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Receiving Chemoradiotherapy. Current Oncology, 33(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010005