An Integrative Review to Examine the Care Pathways and Support Available for Individuals Diagnosed with Lung Cancer Who Have Never Smoked

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

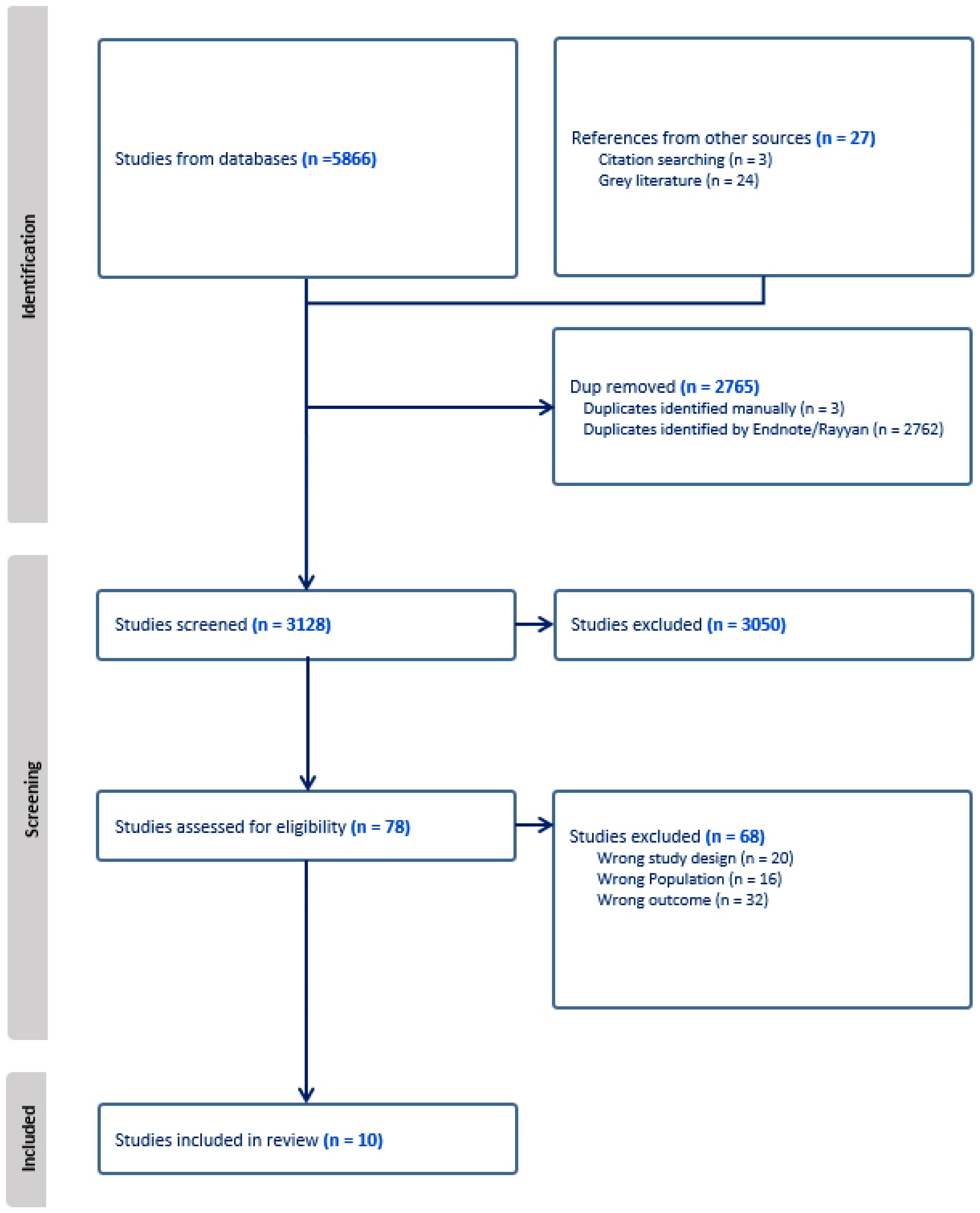

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

- Stigma;

- Awareness;

- Diagnosis;

- The emotional response;

- Support.

3.1. Stigma

3.2. Awareness

3.3. Diagnosis

3.4. Emotional Response

3.5. Support

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- El-Turk, N.; Chou, M.S.H.; Ting, N.C.H.; Girgis, A.; Vinod, S.K.; Bray, V.; Dobler, C.C. Treatment burden experienced by patients with lung cancer. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Lung Cancer in Nonsmokers. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/lung-cancer/nonsmokers/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Dubin, S.; Griffin, D. Lung cancer in non-smokers. Mo. Med. 2020, 117, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pelosof, L.G.; Ahn, C.; Gao, A.; Horn, L.; Madrigales, A.; Cox, J.; McGavic, D.; Minna, J.D.; Gazdar, A.F.; Schiller, J. Proportion of never smoker non-small cell lung cancer patients at three diverse institutions. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopal, A.; Peake, M.D.; Gilligan, D.; Cosford, P. Lung cancer in never-smokers: A hidden disease. J. R. Soc. Med. 2019, 112, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoPiccolo, J.; Gusev, A.; Christiani, D.C.; Jänne, P.A. Lung cancer in patients who have never smoked—An emerging disease. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, A.; Woods, S.; Dunne, S.; Gallagher, P. Unmet supportive care needs associated with quality of life for people with lung cancer: A systematic review of the evidence 2007–2020. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 2022, 31, e13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schomerus, G.; Leonhard, A.; Manthey, J.; Morris, J.; Neufeld, M.; Kilian, C.; Speerforck, S.; Winkler, P.; Corrigan, P.W. The stigma of alcohol related liver disease and its impact on healthcare. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawfal, E.S.; Gray, A.; Sheehan, D.M.; Ibañez, G.E.; Trepka, M.J. A systematic review of the impact of HIV related stigma and serostatus disclosure on retention in care and antiretroviral therapy adherence among women with HIV in the United States/Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2024, 38, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S.K.; Dunn, J.; Occhipinti, S.; Hughes, S.; Baade, P.; Sinclair, S.; Aitken, J.; Youl, P.; O’Connell, D.L. A systematic review of the impact of stigma and nihilism on lung cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.; Pandya, T.; Swanton, C.; Solomon, B.J. Lung cancer in nonsmoking individuals: A review. JAMA 2025, 334, 1836–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, G.A.; Young, R.P.; Tanner, N.T.; Mazzone, P. Screening low-risk individuals for lung cancer: The need may be present, but the evidence of benefit is not. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. 2006. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, R. The Lived Experience of Lung Cancer for Never Smokers. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella Univeristy, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, D.; O’Connor, J.M.; Jatoi, A.; Ridgeway, J.; Deering, E.; Schwecke, A.; Radecki Breitkopf, C.; Huston, O.; Le Rademacher, J.G. A qualitative study of healthcare-related experiences of non-smoking women with lung cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung Cancer Europe (LuCE). Challenges in the Care Pathway and Preferences of People with Lung Cancer in Europe: 7th LuCE Report 2022. Available online: https://www.lungcancereurope.eu/2022/11/29/7th-edition-of-the-luce-report-chalenges-in-the-care-pathway-and-preferences-of-people-with-lung-cancer-in-europe/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Black, G.B.; van Os, S.; Whitaker, K.L.; Hawkins, G.S.; Quaife, S.L. What are the similarities and differences in lung cancer symptom appraisal and help seeking according to smoking status? A qualitative study with lung cancer patients. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Hatton, N.; Tough, D.; Rintoul, R.C.; Pepper, C.; Calman, L.; McDonald, F.; Harris, C.; Randle, A.; Turner, M.C.; et al. Lung cancer in never smokers (LCINS): Development of a UK national research strategy. BJC Rep. 2023, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, G.B.; Janes, S.M.; Callister, M.E.J.; van Os, S.; Whitaker, K.L.; Quaife, S.L. The role of smoking status in making risk-informed diagnostic decisions in the lung cancer pathway: A qualitative study of health care professionals and patients. Med. Decis. Mak. 2024, 44, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criswell, K.R.; Owen, J.E.; Thornton, A.A.; Stanton, A.L. Personal responsibility, regret, and medical stigma among individuals living with lung cancer. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 39, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, T.J.; Choi, A.K.; Kim, J.C.; Garon, E.B.; Shapiro, J.R.; Irwin, M.R.; Goldman, J.W.; Bornyazan, K.; Carroll, J.M.; Stanton, A.L. A longitudinal investigation of internalized stigma, constrained disclosure, and quality of life across 12 weeks in lung cancer patients on active oncologic treatment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, T.J.; Kwon, D.M.; Riley, K.E.; Shen, M.J.; Hamann, H.A.; Ostroff, J.S. Lung cancer stigma: Does smoking history matter? Ann. Behav. Med. 2020, 54, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.; Beattie, K.; Montague, D. The role of UK oncogene focused patient groups in supporting and educating patients with oncogene driven NSCLC: Results from a patient devised survey. Oncol. Ther. 2021, 9, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, S.K.; Baade, P.; Youl, P.; Aitken, J.; Occhipinti, S.; Vinod, S.; Valery, P.C.; Garvey, G.; Fong, K.M.; Ball, D.; et al. Psychological distress and quality of life in lung cancer: The role of health-related stigma, illness appraisals and social constraints. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Son, H.; Han, G.; Kim, T. Stigma and quality of life in lung cancer patients: The mediating effect of distress and the moderated mediating effect of social support. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 11, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Exploring psychological distress among lung cancer patients through the stress system model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.-H.; Liu, Y.; Hsu, H.-T.; Kao, C.-C. Cancer fear, emotion regulation, and emotional distress in patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2024, 47, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, E.J.; Novotny, P.J.; Sloan, J.A.; Yang, P.; Patten, C.A.; Ruddy, K.J.; Clark, M.M. Emotional problems, quality of life, and symptom burden in patients with lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2017, 18, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolazco, J.I.; Chang, S.L. The role of health-related quality of life in improving cancer outcomes. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2023, 9, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, H.; Schuler, M.; Richard, M.; Heckl, U.; Weis, J.; Küffner, R. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, R.H. Psychosocial challenges for patients with advanced lung cancer: Interventions to improve well-being. Lung Cancer Targets Ther. 2017, 8, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadsuan, J.; Lai, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Chen, M.-R. The effectiveness of exercise interventions on psychological distress in patients with lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Surviv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki-Tan, J.; Harrison, N.J.; Marshall, H.; Gartner, C.; Runge, C.E.; Morphett, K. Interventions to reduce lung cancer and COPD-related stigma: A systematic review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2024, 58, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K.E.; Ulrich, M.R.; Hamann, H.A.; Ostroff, J.S. Decreasing Smoking but Increasing Stigma? Anti-tobacco Campaigns, Public Health, and Cancer Care. AMA J. Ethics 2017, 19, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth Strauss Foundation. Non-Smoking Lung Cancers. Ruth Strauss Foundation. Available online: https://ruthstraussfoundation.com/professionals/non-smoking-lung-cancer/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation. Let Go of the Labels. Liverpool: Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation. 2024; Available online: https://www.roycastle.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Hamilton, W.; Walter, F.M.; Rubin, G.; Neal, R.D. Improving early diagnosis of symptomatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casal Mouriño, A.; Valdés, L.; Barros Dios, J.M.; Ruano Ravina, A. Lung cancer survival among never smokers. Cancer Lett. 2019, 451, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Housten, A.J.; Gunn, C.M.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Basen-Engquist, K.M. Health literacy interventions in cancer: A systematic review. J. Canc. Educ. 2021, 36, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ironmonger, L.; Ohuma, E.; Ormiston-Smith, N.; Gildea, C.; Thomson, C.S.; Peake, M.D. An evaluation of the impact of large-scale interventions to raise public awareness of a lung cancer symptom. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.P.T.; Cheyne, L.; Darby, M.; Plant, P.; Milton, R.; Robson, J.M.; Gill, A.; Malhotra, P.; Ashford-Turner, V.; Rodger, K.; et al. Lung cancer stage-shift following a symptom awareness campaign. Thorax 2018, 73, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Hu, X. Peer support interventions on quality of life, depression, anxiety, and self-efficacy among patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 3213–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.; Finnis, A.; Khan, H.; Ejbye, J. At the Heart of Health: Realising the Value of People and Communities; Nesta & The Health Foundation: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Patient Power. Lung Cancer. Medically Reviewed by Natalie Vokes, MD; Updated 21 April 2023. Available online: https://www.patientpower.info/lung-cancer/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Walsh, C.A.; Al Achkar, M. A qualitative study of online support communities for lung cancer survivors on targeted therapies. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4493–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | “Never-smok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Never smok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Non-smok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Non smok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Nonsmok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Don’t smok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Never-Tobacco” [Title/Abstract] OR “Never Tobacco”[Title/Abstract] OR “Non-tobacco”[Title/Abstract] OR “Non tobacco”[Title/Abstract] OR “Nontobacco”[Title/Abstract] OR “Never-cigar*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Never cigar*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Passive smok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Involuntary smok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Second-hand smok*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Non-Smokers”[Mesh] OR “Tobacco Smoke Pollution”[Mesh]data |

| AND | |

| Exposure | “Lung cancer”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pulmonary cancer”[Title/Abstract] OR “Cancer of the Lung”[Title/Abstract] OR “Lung carcinoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pulmonary carcinoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “Carcinoma of the lung”[Title/Abstract] OR “Lung neoplasm”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pulmonary neoplasm”[Title/Abstract] OR “Small cell lung cancer”[Title/Abstract] OR “Non-small cell lung cancer”[Title/Abstract] OR “Lung neoplasm”[Title/Abstract] OR “ALK-positive”[Title/Abstract] OR “Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase”[Title/Abstract] OR “lung tumor*”[Title/Abstract] OR “EGFR-positive”[Title/Abstract] OR “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor”[Title/Abstract] OR “Lung Neoplasms”[Mesh] OR “Small Cell Lung Carcinoma”[Mesh] OR “Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung”[Mesh] OR “Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase”[Mesh] OR “ErbB Receptors”[Mesh] data |

| AND | |

| Outcome | “Guidance”[Title/Abstract] OR “Support”[Title/Abstract] OR “Help”[Title/Abstract] OR “Assistance”[Title/Abstract] OR “Experience*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Impact”[Title/Abstract] OR “Burden”[Title/Abstract] OR “Care”[Title/Abstract] OR “Treatment*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Diagnos*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Pathway*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Screening”[Title/Abstract] OR “Early-diagnosi*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Presentation”[Title/Abstract] OR “Barrier*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Detection”[Title/Abstract] OR “Management”[Title/Abstract] OR “Therap*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Treatment Outcome”[Mesh] OR “Treatment Failure”[Mesh] OR “Treatment Delay”[Mesh] OR “Time-to-Treatment”[Mesh] OR “Critical Pathways”[Mesh] OR “Diagnosis”[Mesh] OR “Delayed Diagnosis”[Mesh] OR “Early Diagnosis”[Mesh] OR “Missed Diagnosis”[Mesh] OR “Early Detection of Cancer”[Mesh] OR “Health Impact Assessment”[Mesh] OR “Mass Screening”[Mesh] OR “Disease Management”[Mesh] OR “Disease Management”[Mesh] |

| Author (Year) | Country | Study Aims | Participants | Study Design | Key Findings/Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott, Beattie, and Montague (2021) [29] | Worldwide (Charities based in the UK) | To provide insight into support groups for individuals with ALK+, EGFR+, and ROS1 lung cancer mutations. | 167 lung cancer patients | Quantitative cross-sectional survey | Support groups are “extremely” or “very” valuable to most lung cancer patient participants (91.6%) with an oncogene mutation and represent a valuable tool in supporting them. More could be done through the groups to combat loneliness and help patients “advocate for better care”. |

| Black et al. (2022) [22] | UK | To explore the different diagnostic experiences of individuals diagnosed with lung cancer depending on smoking status. | 40 lung cancer patients | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | Individuals who have never smoked are less vigilant about lung cancer symptoms and more likely to accept an initial alternative diagnosis. |

| Black et al. (2024) [23] | UK | To better understand how smoking history affects risk-informed decision-making in the lung cancer diagnostic pathway. | 20 never smoker lung cancer patients; 10 clinicians | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | There is a need to improve awareness of lung cancer in never smokers amongst clinicians, and guidance should be updated to avoid delays to diagnosis caused by overreliance on smoking history as a marker. |

| Brandt (2015) [20] | USA | To explore the experiences of individuals diagnosed with lung cancer who have never smoked. | 10 never smoker lung cancer patients | Qualitative phenomenological, unstructured interviews | The experience of lung cancer in never smokers is uniquely challenging, emotionally complex, and under-recognised in both research and clinical care. |

| Criswell et al. (2016) [26] | USA | To explore rates and intensity of regret, personal responsibility, and medical stigma amongst individuals with a lung cancer diagnosis with different smoking histories, and to measure their impact on psychosocial and health-related outcomes. | 213 lung cancer patients | Quantitative cross-sectional survey | Ever and current smokers experienced significantly higher levels of regret and personal responsibility than never smokers, but all groups experienced medical stigma to a similar degree. Associations between all factors of the Cancer Responsibility and Regret Scale and depressive symptoms were significantly higher in never smokers, suggesting that this group could be more adversely affected by regret, personal responsibility, and medical stigma. |

| Dao et al. (2019) [21] | USA | To explore the consequences of stigma from the perspective of non-smoking women with lung cancer, with a focus on healthcare, to better understand how this information can influence providers. | 23 lung cancer patients | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | The diagnosis of lung cancer was emotionally difficult, and individuals felt that the diagnosis of their cancer had been delayed as a result of their smoking status. |

| Khan et al. (2023) [24] | UK | To determine the areas in need of further study to promote better outcomes for individuals with lung cancer who have never smoked tobacco. | 127 stakeholder survey participants; 190 stakeholders took part in consensus work | Qualitative cross-sectional survey and consensus work | Areas of concern for further research included delayed diagnosis, the need to increase knowledge of lung cancer in never smokers, the need to increase awareness of other causes beyond smoking, and further research into the care pathway. There is a need to tackle the stigma attached to a diagnosis. |

| Lung Cancer Europe (2022) [22] | Europe | To explore lung cancer patients’ experiences of the care pathway, from diagnosis to treatment and follow-up. | 991 lung cancer patients | Qualitative cross-sectional survey | There is a need to speed up the diagnostics process, provide more support for patients on the treatment pathway, and improve supportive care for all lung cancer patients. There is a suggestion that never smokers experience each of these differently, but there is limited data as to how. |

| Williamson et al. (2018) [27] | USA | To explore the association between internalised stigma and constrained disclosure, with quality of life and associated physical and mental well-being. | 101 lung cancer patients | Quantitative longitudinal survey | Never smokers reported less internalised stigma than former smokers (p = 0.013) and current smokers (p = 0.001). There was a significant association between higher levels of internalised stigma and declining emotional well-being at 6 (p = 0.002 and 12 weeks (p = 0.004). |

| Williamson et al. (2020) [28] | USA | To discover if there is a relationship between smoking status and lung cancer stigma amongst patients, and if there is a link with depressive symptoms. | 266 lung cancer patients | Quantitative cross-sectional survey | Current smokers scored significantly more for total lung cancer stigma than former smokers (p = 0.003) and never smokers (p < 0.001). Lung cancer stigma scores are strongly associated with higher depressive symptoms, irrespective of smoking status (all p < 0.001). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dodd, C.; Henshall, C.; Jain, M.; Davey, Z. An Integrative Review to Examine the Care Pathways and Support Available for Individuals Diagnosed with Lung Cancer Who Have Never Smoked. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010004

Dodd C, Henshall C, Jain M, Davey Z. An Integrative Review to Examine the Care Pathways and Support Available for Individuals Diagnosed with Lung Cancer Who Have Never Smoked. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleDodd, Christopher, Catherine Henshall, Mohini Jain, and Zoe Davey. 2026. "An Integrative Review to Examine the Care Pathways and Support Available for Individuals Diagnosed with Lung Cancer Who Have Never Smoked" Current Oncology 33, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010004

APA StyleDodd, C., Henshall, C., Jain, M., & Davey, Z. (2026). An Integrative Review to Examine the Care Pathways and Support Available for Individuals Diagnosed with Lung Cancer Who Have Never Smoked. Current Oncology, 33(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010004