Trajectories of Posttraumatic Growth Among Latvian Parents of Children with Cancer: A Mixed Methods Approach

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Which latent class model best explains the heterogeneity in PTG outcomes among Latvian parents of CCSs, based on mean differences across identified subgroups?

- (2)

- What are the differences in psychosocial factors (i.e., sociodemographic and personality traits, initial stress reactions, illness cognitions, coping strategies, and PTSS) in the identified latent classes?

- (3)

- What are the parents’ experiences of PTG following their children’s cancer treatment?

- (4)

- How do the quantitative and qualitative sets of results develop a more comprehensive understanding of PTG in parents of CCSs?

2. Materials and Methods

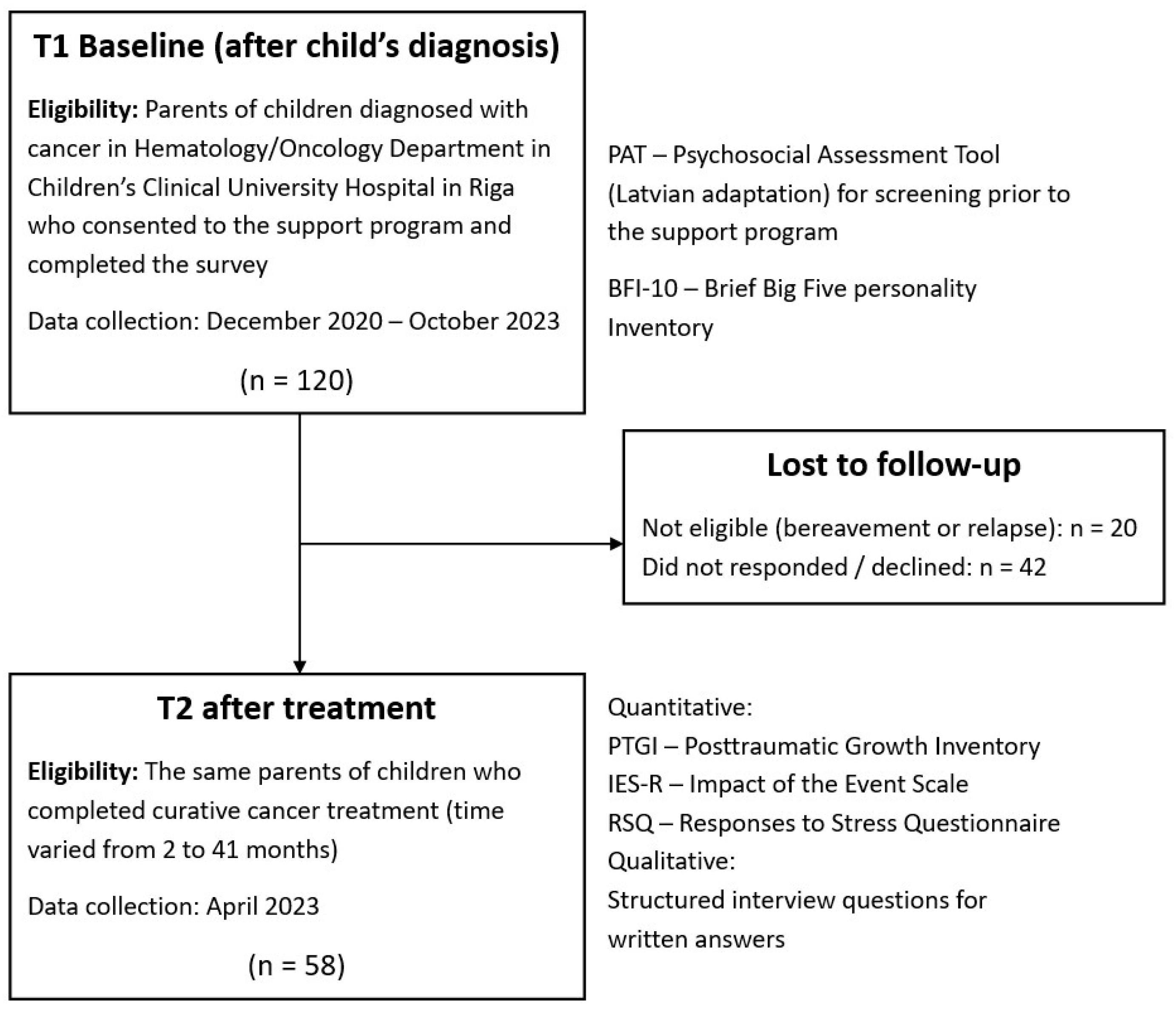

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Screening Measures at T1

- The Latvian version of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) [39], derived from PAT 2.0 and PAT 3.1 [40], evaluates psychosocial risks faced by families across five areas, two of which are included in this analysis: ‘Stress Reactions after Diagnosis’ and ‘Family Beliefs’. The ‘Stress Reactions’ subscale addresses the initial stress responses of parents immediately following a diagnosis, including feelings like mood swings, nightmares related to the child’s illness, physical discomfort when discussing the diagnosis, and difficulties relaxing due to heightened stress. The ‘Family Beliefs’ subscale comprises both positive and significantly negative thoughts related to cancer (e.g., “The doctors will know what to do” and “Cancer is a death sentence”).

- The Big Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10) [41] is a concise self-assessment tool consisting of 10 items (5-point Likert scale) that measures five personality traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.

2.3.2. Outcome Measures at T2

- The Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) [5] is another self-report questionnaire with 21 items (6-point Likert scale) that assesses five domains of PTG: ‘Relation to others’, ‘New possibilities’, ‘Personal strength’, ‘Spiritual change’, and ‘Appreciation of life’.

- The Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) [42] is a self-report survey for PTSS that includes 22 items (5-point Likert scale) across three subscales: ‘Intrusion’ (which covers intrusive thoughts and nightmares), ‘Avoidance’ (including emotional numbness and avoidance of feelings or situations), and ‘Hyperarousal’ (characterized by irritability and hypervigilance).

- The Responses to Stress Questionnaire (RSQ) [43], the Survivors’ version, is a self-report questionnaire focused on parental coping strategies. It contains 57 items (4-point Likert scale) and is structured into five subscales. At the highest level, coping is categorized as Engagement or Disengagement. Engagement coping is further divided into ‘Primary Control Engagement’ (involving problem-solving, emotional expression, and emotional regulation) and ‘Secondary Control Engagement’ (including cognitive restructuring, positive thinking, and acceptance). ‘Disengagement Coping’ involves strategies like avoidance, denial, wishful thinking, and distraction. Two additional subscales capture involuntary responses to stress: ‘Involuntary Engagement’ (e.g., rumination and impulsive actions) and ‘Involuntary Disengagement’ (e.g., cognitive interference and numbing).

- A short, structured interview with open-ended questions for written answers (e.g., “It is believed that a child’s cancer diagnosis and prolonged treatment can significantly impact parents. Some of these changes may resonate with you, some you may not like. Have you noticed any differences in yourself compared to before? In what ways have you changed?”) was employed to explore changes following a child’s cancer treatment. The qualitative questions were informed by the semi-structured Impact of Traumatic Stressors Interview Schedule (ITSIS) [44]. Thematic analysis was conducted to identify and describe the key experiences of growth derived from the qualitative data.

2.4. Data Analytics Plan

2.4.1. Bayesian Latent Class Analysis

2.4.2. Thematic Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses and Correlation Overview

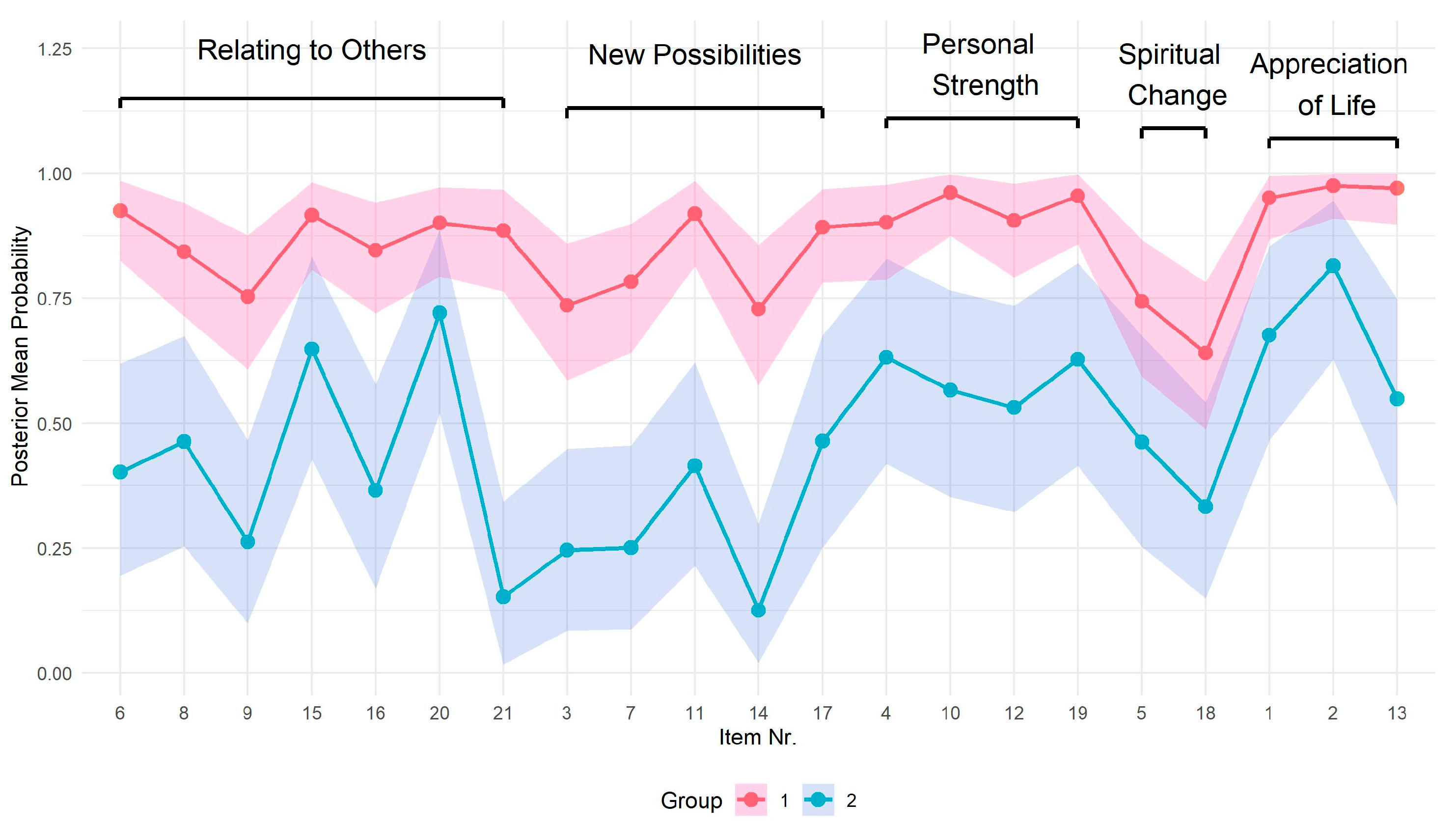

3.2. Latent Class Analysis of Parental PTG Following Childhood Cancer

3.2.1. Sociodemographic Factors

3.2.2. Personality Traits

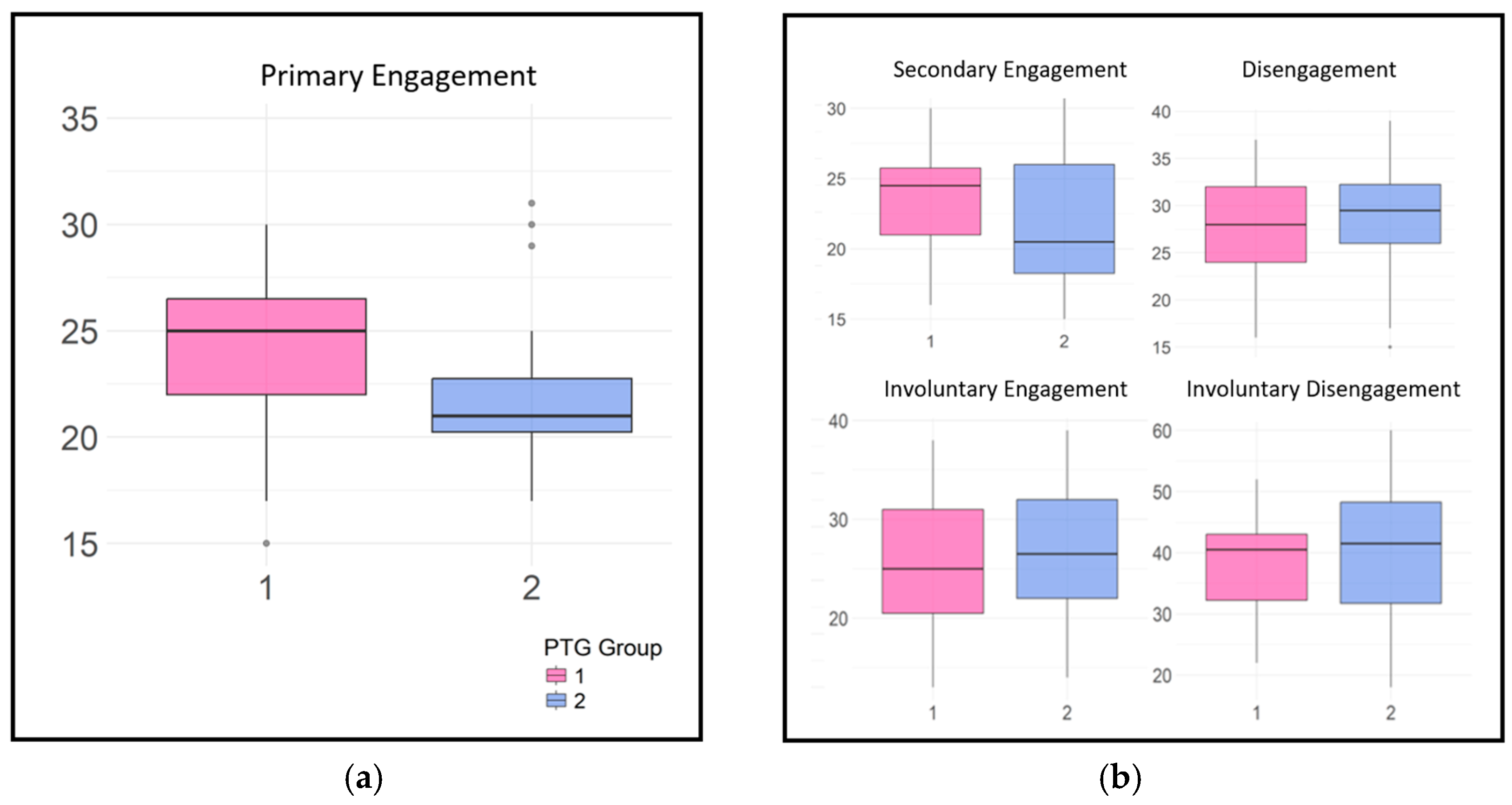

3.2.3. Coping Strategies

3.2.4. Psychosocial Factors After Diagnosis

May 19, when the doctor called me in to inform me about the diagnosis. Shock, the inability to accept that this is happening to my child, and that what is about to begin will also become a part of my life. You’re facing something with no known endpoint or measurable distance. A day when you’re left with the thought that you lack the ability to take responsibility for your own tomorrow, or perhaps for the rest of your life.(Mother, 46B)

The very beginning at BKUS, in ward 10, right after the diagnosis was announced and we were transferred to this ward—I didn’t know anyone, I didn’t know the ward rules (mask-wearing, not being able to meet freely, accidentally breaking some rule and getting corrected for it), I didn’t know what to expect—all combined with my own emotions, when I could suddenly start crying out of nowhere (and I really dislike crying when others can see it).(Mother, 33B)

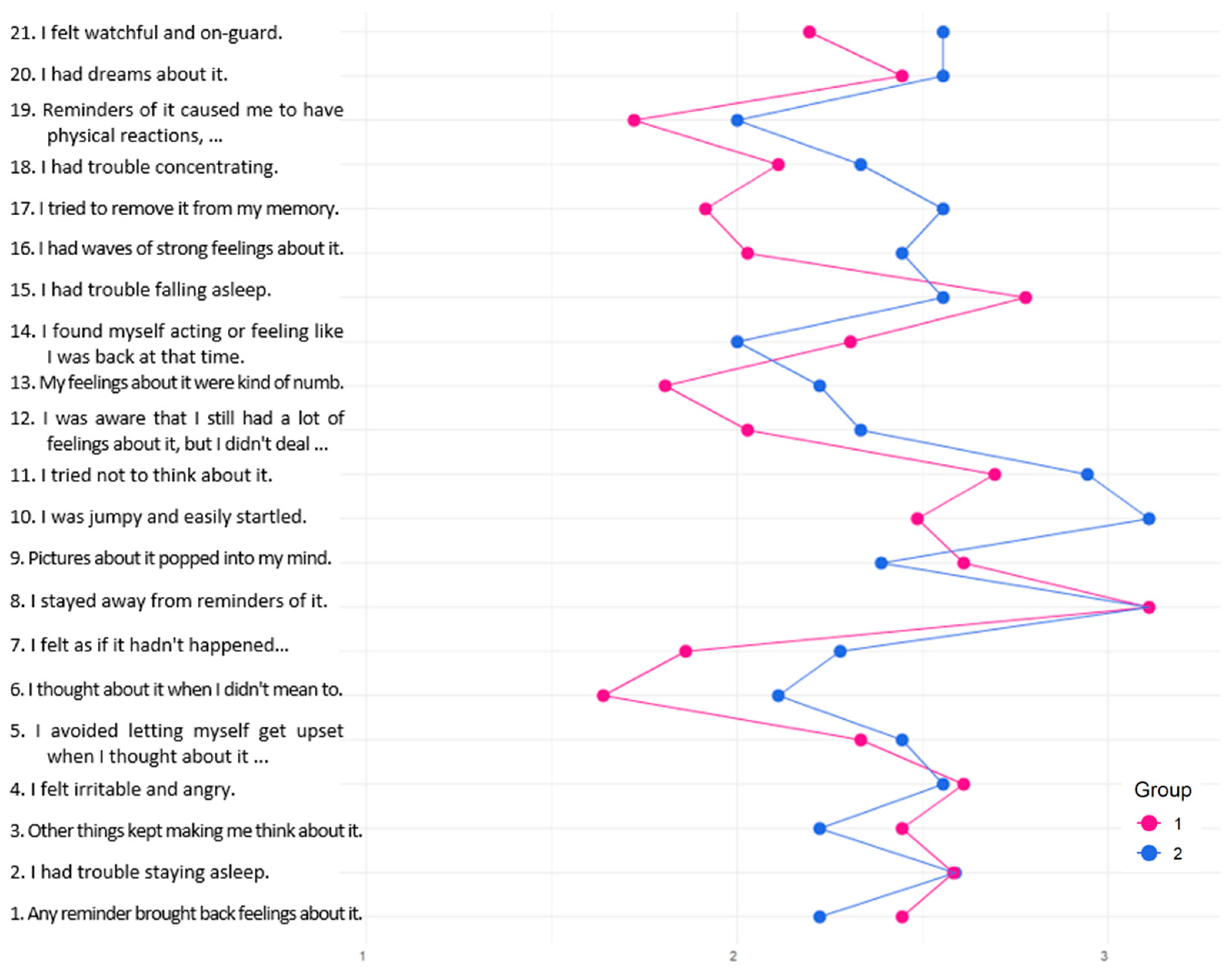

3.2.5. Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms

3.3. Mixed Methods Approach to Parental PTG in Childhood Cancer

“I’ve become calmer about the big things in life because I’m no longer as afraid. But the joy of life is gone—it no longer feels easy.”(G1, 31B)

“And once again—both difficult experiences [divorce and child’s cancer] shaped the changes in me, as they happened simultaneously. I’ve become much braver, more assertive, and more demanding—yet at the same time, more hesitant when it comes to trust. I’ve become less open, more inwardly reserved, yet simultaneously more empathetic and emotionally calm. I now deeply appreciate the things I once took for granted, value the genuine people around me, and love and protect those who are truly mine even more. As my psychologist said after a full year of sessions, I’ve become much stronger.”(G1, 32B)

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison to Previous Research and Novelty

4.2. Latent Classes and Correlates of PTG: Personality, Coping, and Social Network

4.3. Qualitative Indicators of Dynamic PTG Within a Mixed Methods Framework

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lam, C.G.; Howard, S.C.; Bouffet, E.; Pritchard-Jones, K. Science and health for all children with cancer. Science 2019, 363, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botta, L.; Gatta, G.; Capocaccia, R.; Stiller, C.; Cañete, A.; Dal Maso, L.; Innos, K.; Mihor, A.; Erdmann, F.; Spix, C.; et al. Long-term survival and cure fraction estimates for childhood cancer in Europe (EUROCARE-6): Results from a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungman, L.; Hovén, E.; Ljungman, G.; Cernvall, M.; von Essen, L. Does time heal all wounds? A longitudinal study of the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of survivors of childhood cancer and bereaved parents. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lietaviete, I.; Martinsone, B. Parental perceptions of childhood cancer in Latvia: Coping and outcomes. In Human, Technologies and Quality of Education, 2024, Proceedings of Scientific Papers = Cilvēks, Tehnoloģijas un Izglītības Kvalitāte, 2024. Rakstu Krājums; Daniela, L., Ed.; University of Latvia Press: Riga, Latvia, 2024; pp. 409–423. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Taku, K.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R. The goal, rationale, and organization of the book. In The Routledge International Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth; Berger, R., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Koutrouli, N.; Anagnostopoulos, F.; Potamianos, G. Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Women Health 2012, 52, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, W.J.; Wang, X.Q.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.H.; Sun, J.R.; Lei, S.Y.; Liao, C.Y.; Wang, M.X. Research trends of posttraumatic growth from 1996 to 2020: A bibliometric analysis based on Web of Science and CiteSpace. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 3, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.M.Y.; Cheng, C.T. Illusory versus constructive posttraumatic growth in cancer. In The Routledge International Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth; Berger, R., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Lurie-Beck, J. A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, E.K.; da Silva Oliveira, J.A.; Armiliato, M.J.; Peloso, F.; Valentini, F. Profiles of posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress symptoms in childhood cancer survivors. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2024, 17, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, E.K.; Giacomoni, C. Features of posttraumatic growth of children with cancer. In Handbook of the Behavior and Psychology of Disease; Martin, C.R., Preedy, V.R., Patel, V.B., Rajendram, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Wang, G.; Ho, S.M.Y. The relationship between types of posttraumatic growth and prospective psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer: A follow-up study. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 586–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, O.; Zebrack, B.; Block, R.; Embry, L.; Aguilar, C.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Cole, S. Posttraumatic growth and well-being among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer: A longitudinal study. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2881–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawickreme, E.; Blackie, L.E.R. Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Evidence, controversies and future directions. Eur. J. Pers. 2014, 28, 312–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Gow, K.; Smith, S. Personality, coping and posttraumatic growth in emergency ambulance personnel. Traumatology 2005, 11, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauer, K.; Bach, A.; Schäffeler, N.; Stengel, A.; Graf, J. Personality traits and coping strategies relevant to posttraumatic growth in patients with cancer and survivors: A systematic literature review. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 9593–9612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Ortiz, G.; Noriega, C. Posttraumatic growth in parents of children and adolescents with cancer. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2019, 42, 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- Baenziger, J.; Roser, K.; Mader, L.; Ilic, A.; Sansom-Daly, U.M.; von Bueren, A.O.; Tinner, E.M.; Michel, G. Post-traumatic growth in parents of long-term childhood cancer survivors compared to the general population: A report from the Swiss childhood cancer survivor study—Parents. Psycho-Oncology 2024, 33, e6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meral, B.; Bulut, H.K. Predictors of moderate-high posttraumatic growth in parents of children with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloso, F.C.; Gonçalves, T.; Armiliato, M.J.; Gregianin, L.; Ramos, C.; de Castro, E.K. Posttraumatic growth among childhood cancer survivors and their caregivers: Associations with rumination and beliefs challenge. Psicooncologia 2022, 19, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Park, H.R.; Choi, S.H. Posttraumatic growth of adolescents with childhood leukemia and their parents. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2019, 25, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, B. Posttraumatic growth as experienced by childhood cancer survivors and their families. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 30, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halldorsdottir, B.; Michel, G.; Baenziger, J. Post-traumatic growth in family members of childhood cancer survivors—An updated systematic review. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2022, 4, e6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, A.; Jenewein, J. Resilience in cancer patients. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Thayer, W.M.; Bridges, J.F.P. Using latent class analysis to model preference heterogeneity in health: A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 2018, 36, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlin, K.S.; Williams, N.A.; Parra, G.R. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Sun, J.; Zhao, K.; He, M.; Yuan, C.; Fu, L.; Shen, N. Subjective toxicity profiles of children with cancer during treatment. Cancer Nurs. 2024, 47, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; Wang, J.; Greenzang, K.A.; McFatrich, M.; Hinds, P.S. The predictive trifecta? Fatigue, pain, and anxiety severity forecast the suffering profile of children with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 2081–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Luo, Y.; Xiong, W.; Meng, Z.; Yu, N.X.; Zhang, J. Latent profiles of problem-solving skills and their association with depressive symptoms in parents of children with cancer: A cross-sectional study. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 12, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Bi, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, Q.; Ma, L.; Geng, Z.; Yuan, C. Supportive care needs of parents caring for children with leukemia: A latent profile analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, D.E.; Narcisse, M.; James, L.; Selig, J.P.; Ason, M.; Scott, A.J.; Cornett, L.E.; McElfish, P.A. Vaccine hesitancy or hesitancies? A latent class analysis of pediatric patients’ parents. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2025, 18, e70042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, A.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, J. A latent class analysis of resilience and its relationship with depressive symptoms in the parents of children with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4379–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard Sharp, K.M.; Tillery Webster, R.; Cook, J.; Okado, Y.; Long, A.; Phipps, S. Profiles of resilience, distress, and posttraumatic growth in parents of children with cancer and the relation to subsequent parenting and family functioning. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 48, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Al Omari, O.; Roach, E.J.; Shakman, L.; Al Hashmi, A.; Sunderraj, S.J.; Francis, F.; Joseph, M.A. The lived experiences of mothers who are parenting children with leukemia. Cancer Nurs. 2021, 44, e374–e381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lietaviete, I. Towards a new model of personalized multidisciplinary care for children with cancer and their families. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2023, 5 (Suppl. S1), 116. [Google Scholar]

- Lietaviete, I.; Martinsone, B. Illness cognitions and parental stress symptoms following a child’s cancer diagnosis. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1436231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.E.; Hwang, W.T.; Chen, F.F.; Askins, M.A.; Carlson, O.; Argueta-Ortiz, F.; Barakat, L.P. Screening for family psychosocial risk in pediatric cancer: Validation of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) version 3. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J. Res. Pers. 2007, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Keane, T.M., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith, J.K.; Compas, B.E.; Wadsworth, M.E.; Thomsen, A.H.; Saltzman, H. Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 976–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.; Stuber, M.; Barakat, L.; Meeske, K. Assessing Posttraumatic Stress Related to Medical Illness and Treatment: The Impact of Traumatic Stressors Interview Schedule (ITSIS). Fam. Syst. Health 1996, 14, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lord-Bessen, J.; Shiyko, M.; Loeb, R. Bayesian latent class analysis tutorial. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Murphy, T.B. BayesLCA: An R Package for Bayesian Latent Class Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 61, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, W.; Shiwaku, H.; Taku, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Inoue, Y. Roles of reexamination of core beliefs and rumination in posttraumatic growth among parents of children with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2021, 44, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, S.; Long, A.; Willard, V.W.; Okado, Y.; Hudson, M.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Noll, R. Parents of children with cancer: At-risk or resilient? J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 40, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boals, A. Illusory posttraumatic growth is common, but genuine posttraumatic growth is rare: A critical review and suggestions for a path forward. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 103, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockton, H.; Hunt, N.; Joseph, S. Cognitive processing, rumination, and posttraumatic growth. J. Trauma Stress 2011, 24, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Blevins, C.L. From mindfulness to meaning: Implications for the theory of posttraumatic growth. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y. Factors influencing posttraumatic growth in mothers of children with cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 34, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Kilmer, R.P.; Gil-Rivas, V.; Vishnevsky, T.; Danhauer, S.C. The Core Beliefs Inventory: A brief measure of disruption in the assumptive world. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.L. Insights into processes of posttraumatic growth through narrative analysis of chronic illness stories. Qual. Psychol. 2015, 2, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietaviete, I. What happened to us: Psychosocial assessment, cognitive beliefs and parent’s adjustment to childhood cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2023, 5 (Suppl. S1), 142. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, L.P.; Madden, R.E.; Vega, G.; Askins, M.; Kazak, A.E. Longitudinal predictors of caregiver resilience outcomes at the end of childhood cancer treatment. Psycho-Oncol. 2021, 30, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, L.P.; Alderfer, M.A.; Kazak, A.E. Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2006, 31, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.H.; Mrug, S.; Schwebel, D.C.; Phipps, S.; Whelan, K.; Madan-Swain, A. Benefit finding and quality of life in caregivers of childhood cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2017, 40, e28–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Murguía, M.; Guevara-Sanginés, M.L.; Navarro-Contreras, G.; Peralta-Castillo, G.; Padilla-Rico, A.; González-Alcocer, L.; Padrós-Blázquez, F. Relationship between thought style, emotional response, post-traumatic growth (PTG), and biomarkers in cancer patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogińska-Bulik, N.; Socha, I. Emotional processing and negative and positive effects of trauma among parents struggling with cancer of their child. Psychoonkologia 2017, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y. Turning pain into strength: Prosocial behaviours in coping with trauma. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2024, 15, 2330302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M | SD | Range | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTGI—Total | 59.32 | 17.82 | 17–92 | 0.93 |

| Relation to others | 20.85 | 7.72 | 3–33 | 0.86 |

| New possibilities | 12.61 | 5.79 | 0–24 | 0.84 |

| Personal strength | 13.80 | 12.94 | 2–20 | 0.73 |

| Spiritual change | 5.23 | 3.34 | 0–10 | 0.82 |

| Appreciation of life | 11.50 | 12.86 | 0–15 | 0.84 |

| IES-R—Total | 1.81 | 0.57 | 0–3.49 | 0.92 |

| Intrusion | 1.81 | 0.66 | 0–3.61 | 0.84 |

| Avoidance | 1.82 | 0.64 | 0–3.71 | 0.84 |

| Hyperarousal | 1.86 | 0.55 | 0–3.33 | 0.65 |

| RSQ | ||||

| Primary Control Engagement | 23.55 | 4.08 | 15–36 | 0.79 |

| Secondary Control Engagement | 38.28 | 6.13 | 25–53 | 0.63 |

| Disengagement | 59.30 | 8.18 | 41–77 | 0.63 |

| Involuntary Engagement | 38.28 | 9.75 | 18–60 | 0.81 |

| Involuntary Disengagement | 25.12 | 6.97 | 12–39 | 0.81 |

| Measures at T1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | O | A | C | Stress Reactions | Family Beliefs | |

| Measures at T2 IES-R—Total | 0.36 ** | −0.19 | −0.23 | −0.19 | −0.01 | 0.41 ** | 0.22 |

| Intrusion | 0.37 ** | −0.17 | −0.27 * | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.45 *** | 0.20 |

| Avoidance | 0.23 | −0.22 | −0.18 | −0.21 | 0.02 | 0.33 * | 0.25 |

| Hyperarousal | 0.34 * | −0.05 | −0.13 | −0.17 | −0.01 | 0.38 ** | 0.16 |

| PTGI—Total | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.33 * | 0.18 | −0.16 | −0.39 ** |

| Relation to others | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.17 | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.32 * |

| New possibilities | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.12 | −0.12 | −0.30 * |

| Personal strength | −0.45 ** | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.43 ** | 0.25 | −0.30 * | −0.43 ** |

| Spiritual change | 0.07 | −0.13 | −0.15 | 0.12 | 0.15 | −0.02 | −0.19 |

| Appreciation of life | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.15 |

| Coping Strategy (RSQ) | Estimate | Est. Error | Lower (95% CI) | Upper (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Engagement | −0.16 | 0.08 | −0.33 | −0.01 |

| Secondary Engagement | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.22 | 0.08 |

| Disengagement | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.13 |

| Involuntary Engagement | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.09 |

| Involuntary Disengagement | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.13 |

| Subscale of PAT | Estimate | Est. Error | Lower (95% CI) | Upper (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Support | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.17 |

| Child Problems | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.23 | 0.09 |

| Family Problems | 0.18 | 0.30 | −0.41 | 0.78 |

| Stress Reactions | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.12 |

| Family Beliefs | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.17 | 0.21 |

| PTG Domain | Themes Reflecting Changes | G1 Prop. | G2 Prop. | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relating to Others | Improved Family Bonds/ Change in Priorities | 0.16 (6) | 0.10 (2) | I value the time spent with my family. (G1, 50A) I try to work less and spend more time with my family. (G2, 51A) |

| Increased Empathy and Connection | 0.05 (2) | - | I became more inwardly reserved yet simultaneously more empathetic and emotionally calm. (G1, 32B) | |

| Social Withdrawal/ Trust Shift (Negative) | 0.05 (2) | 0.05 (1) | Strangers feel like a threat, acquaintances feel safe. It wasn’t like that before. (G1, 15B) I live in my own world. (G2, 24B) | |

| Relational Strain (Negative) | 0.08 (3) | - | It’s hard for me to listen to other people’s problems, which I wouldn’t call problems anymore. This change might damage relationships. (G1, 63B) | |

| New Possibilities | Behavioral Adaptation and Self-Care Awareness | 0.05 (2) | - | I pay more attention to children’s health, try to spend more time with them. (G1, 27B) |

| Desire to Help Others Through Experience (emerging theme) | - | 0.10 (2) | I want my experience to help someone else, e.g., through conversations with those currently undergoing treatment. (G2, 21A) | |

| Changes in Daily Routine (Negative) | 0.03 (1) | - | I sense physical inactivity, slight irritation about my weight, and drowsiness. My child and work are priorities now. I miss time alone. (G1, 48B) | |

| Personal Strength | Self-Efficacy and Inner Strength | 0.08 (3) | - | Illness showed me how strong I really am! (G1, 40B) |

| Increased Expression/Assertiveness | 0.05 (2) | - | I express my opinion more. (G1, 14A) | |

| Emotional Maturity and Regulation | 0.19 (7) | 0.05 (1) | I’ve become calmer about the big things in life because I’m no longer as afraid. (G1, 31B) I think I’m the same person overall, just more hardened. (G2, 16B) | |

| Reduced Reactivity to Trivial Matters | 0.24 (7) | 0.14 (3) | I don’t worry about little things. Less interest in the insignificant. (G1, 28B) I don’t stress about unimportant things. (G2, 17B) | |

| Increased Anxiety/Stress (Negative) | 0.05 (2) | 0.19 (4) | I worry more, I listen to my inner voice and feelings. (G1, 17A) Lower stress tolerance; even unrelated stress triggers bodily reactions faster. (G2, 21A) | |

| Health Hypervigilance (Negative) | 0.03 (1) | 0.10 (2) | Cautious, more responsible. (G1, 50A) I react paranoidly to every complaint from my child. (G2, 9A) | |

| Emotional Changes (Negative) | 0.11 (4) | 0.10 (2) | I have become angrier, quicker to snap. (G1, 29A) Less joyful attitude toward life. (G2, 33B) | |

| Ongoing Psychological Burden (Negative) | 0.03 (1) | 0.14 (3) | Extreme fatigue has built up. (G1, 46B) I began experiencing insomnia—which I hadn’t had before—and started using antidepressants. (G2, 18A) | |

| Spiritual Change | Spiritual Growth/ Trust in God | 0.05 (2) | 0.05 (1) | I started to believe in God and feel thankful for the good people in life. (G1, 40B) I’m confident and fully convinced of God’s love and the medical quality in Latvia. (G2, 4A) |

| Appreciation of Life | Gratitude and Appreciation of Life | 0.24 (9) | 0.10 (2) | I see everything around me as a gift. (G1, 40B) I’m more appreciative of what I have. (G2, 7A) |

| Perspective Shift/ Change in Values | 0.22 (8) | 0.24 (5) | I’ve come to understand what truly matters in life and don’t focus on external problems. (G1, 55B) Reviewing my values (want to reduce the meaningless elements of life). (G2, 21A) | |

| Mindfulness/ Living in the Moment | 0.14 (5) | 0.05 (1) | I accept each moment and day as a gift, try not to plan because I don’t know what tomorrow brings. (G1, 12A) I try to work less and enjoy the moment with family. (G2, 51A) |

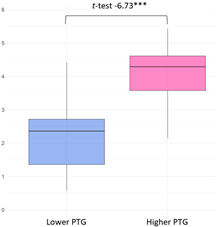

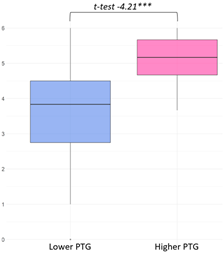

| PTG Domain | Boxplots of Group-Based Variations in PTGI Subscales | Qualitative Subcategories with Examples | Mixed Methods Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relating to Others |  | Improved Family Bonds/Change in Priorities (8 narratives) My life priorities have changed—I value family more than my career. (G2, 30A) I appreciate the seemingly obvious things much more, the genuine people around me; I love and protect those who are mine even more. (G1, 32B) Complete indifference to what others think or might think of me (this is both positive and negative). I value helpful people much more than I did before. (G1, 28A) Increased Empathy and Connection (2) I have become more sensitive. […] [and] rely more on those around me. (G1, 29B) I became more inwardly reserved yet simultaneously more empathetic and emotionally calm. (G1, 32B) | In the lower PTG group (M = 2.25, SD = 1.16), growth within the ‘Relating to Others’ domain showed greater variability, suggesting divergent relational experiences following adversity. Narratives from participants in both groups pointed to a reorientation of relational priorities, characterized by a renewed focus on close family ties and a heightened appreciation for genuinely supportive individuals. Quantitatively, this nuance is reflected in the pattern of item responses: participants reported higher agreement with PTGI item 15 (“I have more compassion for others”), yet lower scores on item 9 (“I am more willing to express my emotions”). This discrepancy suggests that while empathic concern may have increased, emotional openness remained constrained. |

| New Possibilities |  | Behavioral Adaptation and Self-Care Awareness (2) I pay more attention to children’s health, try to spend more time with them. (G1, 27B) Desire to Help Others Through Experience (2) I want my experience to help someone else, e.g., through conversations with those currently undergoing treatment. (G2, 21A) I would like to share our family’s experience with other parents as a source of support and encouragement. (G2, 12A-2) | The marked variability in ‘New Possibilities’ scores suggests ambivalence toward transformative growth. Narrative representation was limited. The prosocial theme—‘Desire to Help Others Through Experience’—unexpectedly emerged only from the lower PTG group. The lower endorsement of items related to new interests and opportunities contrasts with higher agreement on pragmatic change (item 17: “I am more likely to try to change things that need changing”), indicating a preference for practical adaptation over personal reinvention. |

| Personal Strength |  | Self-Efficacy and Inner Strength (3) I have found the strength within myself to ask for help when I need it. (G1, 20B) Increased Expression/Assertiveness (2) I’ve become much braver, more assertive, and more demanding (G1, 32B) Emotional Maturity and Regulation (8) I am more responsible, more mature, more logical now. (G1, 9B) Reduced Reactivity to Trivial Matters (10) I don’t stress about my child’s tantrums and tricks; I let them act out, and then we talk everything through afterward. (G1, 19A) | Parents with higher ‘Personal Strength’ scores on the PTGI often described cognitive–emotional growth in their narratives, particularly in the ‘Personal Strength’ and ‘Relating to Others’ domains. The theme ‘Reduced Reactivity to Trivial Matters’ also aligns with ‘Perspective Shift/Change in Values’ from the ‘Appreciation of Life’ domain, suggesting interconnected changes across domains. In the ‘Personal Strength’ domain, reported growth was frequently accompanied by ongoing anxiety, increased health vigilance, and lasting psychological burden. These patterns appeared more prominently among individuals in the lower PTG group. |

| Spiritual Growth |  | Spiritual Growth/Trust in God (3) Modesty, work, and career are not the most important things in life. (G1, 55A) I started to believe in God and feel thankful for the good people in life. (G1, 40B) I’m confident and fully convinced of God’s love and the quality of Latvian medical care. (G2, 4A) | The ‘Spiritual Change’ domain exhibited the greatest score dispersion among all PTGI subscales. Despite this variability, the difference between the higher and lower PTG groups remained significant, with the lower PTG group showing greater variability, suggesting potential spiritual ambivalence or strain. Narrative representation was limited. Quantitatively, parents more frequently endorsed an increased “understanding of spiritual matters” (item 5), while the “strengthening of religious faith” (item 18) was less commonly reported, indicating a broader, more individualized interpretation of spiritual rather than religious growth. |

| Appreciation of Life |  | Gratitude and Appreciation of Life (11) I see everything around me as a gift. (G1, 40B) I’m much better at appreciating life’s small positive moments! (G1, 19A) Perspective Shift/Change in Values (13) A completely different outlook on life. Different thoughts about people. (G1, 40A) I’ve realized what truly matters in life. (G1, 55B) Mindfulness/Living in the moment (6) The ability to find joy in everyday things and to live in the present moment. (G1, 12B) I live for today. (G1, 55B) | ‘Appreciation of Life’ was the most frequently represented domain across narratives in both groups. High scorers consistently described a heightened awareness of everyday positives and a shift in life priorities, reflecting not just emotional relief but a deeper reorientation of meaning and purpose. However, such responses warrant cautious interpretation, as social desirability and illusory growth may influence self-reports. Importantly, narratives also revealed that gratitude often coexisted with a sharpened sense of life’s fragility, underscoring the complex interplay between appreciation and existential awareness in PTG. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lietaviete, I.; Alksnis, R.; Martinsone, B. Trajectories of Posttraumatic Growth Among Latvian Parents of Children with Cancer: A Mixed Methods Approach. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32090486

Lietaviete I, Alksnis R, Martinsone B. Trajectories of Posttraumatic Growth Among Latvian Parents of Children with Cancer: A Mixed Methods Approach. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(9):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32090486

Chicago/Turabian StyleLietaviete, Inese, Reinis Alksnis, and Baiba Martinsone. 2025. "Trajectories of Posttraumatic Growth Among Latvian Parents of Children with Cancer: A Mixed Methods Approach" Current Oncology 32, no. 9: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32090486

APA StyleLietaviete, I., Alksnis, R., & Martinsone, B. (2025). Trajectories of Posttraumatic Growth Among Latvian Parents of Children with Cancer: A Mixed Methods Approach. Current Oncology, 32(9), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32090486