Assessing Disparities in Who Accepts an Early Palliative Care Consultation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

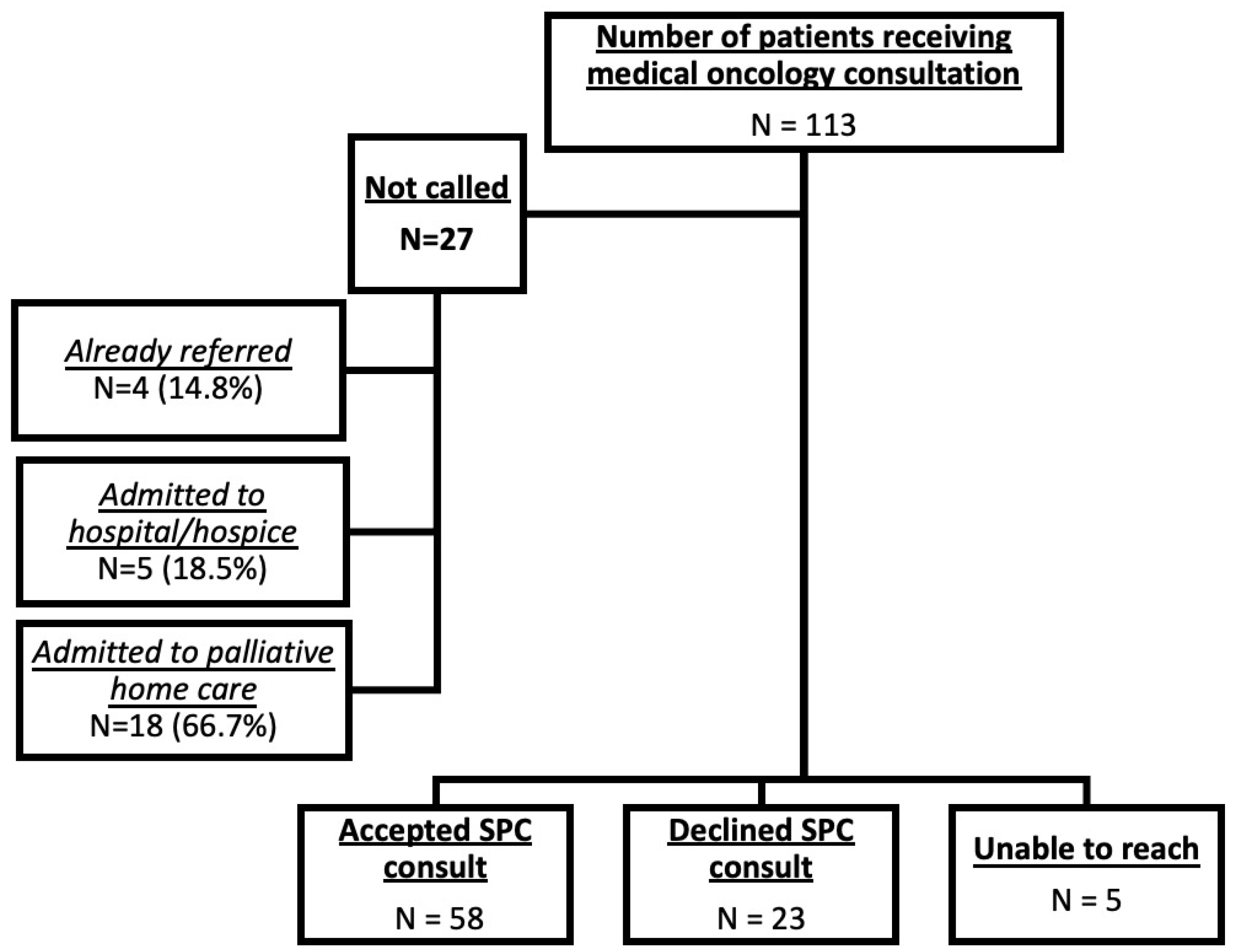

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Univariate Analysis

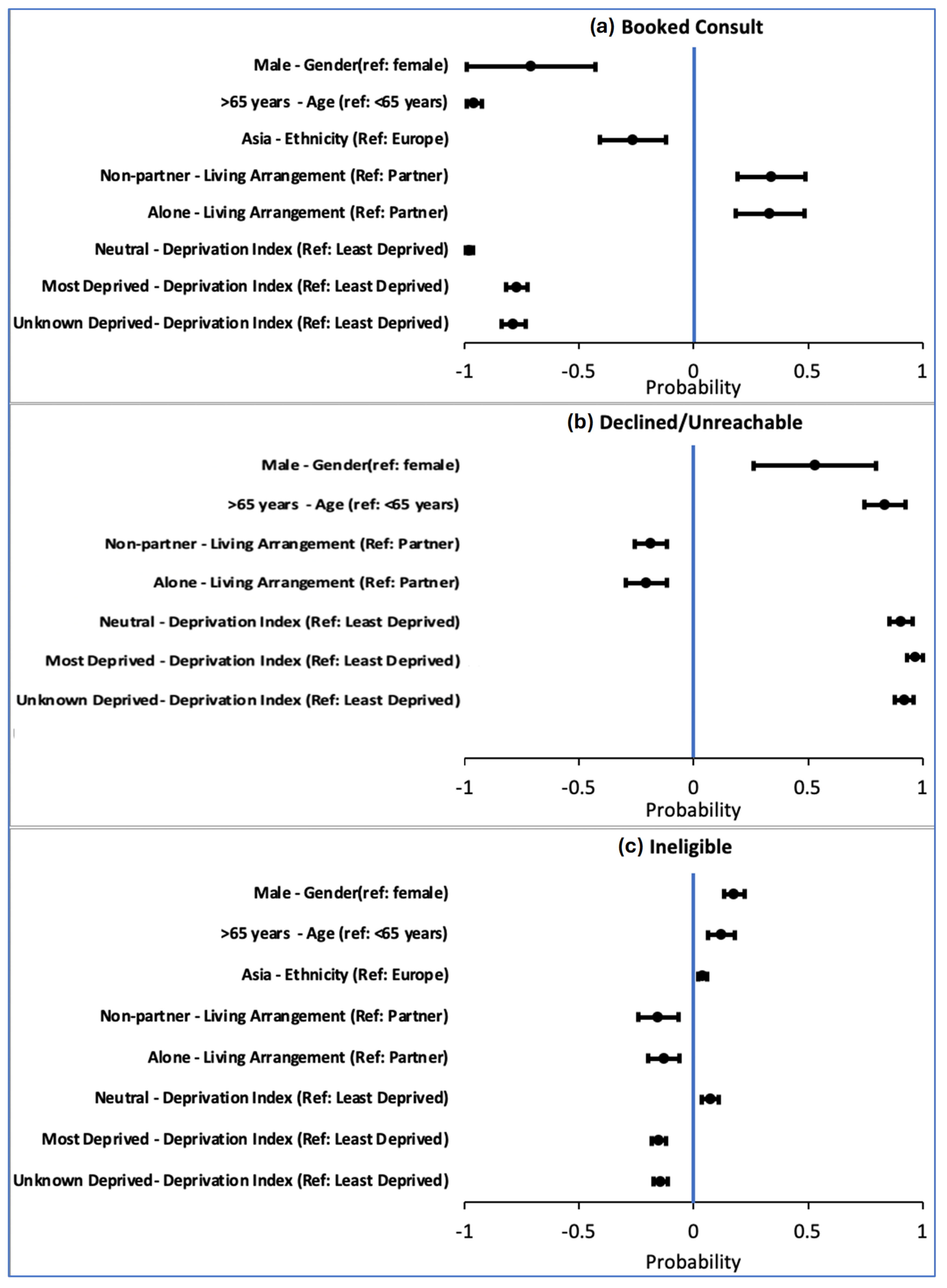

3.3. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SPC | Specialist Palliative Care |

| SES | Socio-Economic Status |

| PaCES | Palliative Care Early and Systematic (project) |

| PROGRESS-Plus | Place of residence, Race/ethnicity, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, Social capital, and additional context-specific factors (Plus) |

References

- Nundy, S.; Cooper, L.A.; Mate, K.S. The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement: A New Imperative to Advance Health Equity. JAMA 2022, 327, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Health Equity. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Krakauer, E.L. Just Palliative Care: Responding Responsibly to the Suffering of the Poor. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 36, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.S. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaul, F.M.; E Farmer, P.; Krakauer, E.L.; De Lima, L.; Bhadelia, A.; Kwete, X.J.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Gómez-Dantés, O.; Rodriguez, N.M.; A O Alleyne, G.; et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—An imperative of universal health coverage: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2018, 391, 1391–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.M.; DiGiacomo, M.; Currow, D.C.; Davidson, P.M. Dying in the margins: Understanding palliative care and socioeco-nomic deprivation in the developed world. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 42, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sítima, G.; Galhardo-Branco, C.; Reis-Pina, P. Equity of access to palliative care: A scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, S.; Earp, M.A.; Biondo, P.; Cheung, W.Y.; Kerba, M.; Tang, P.A.; Shinarajah, A.; Watanabe, S.M.; Simon, J.E. Oncology Clinicians’ Challenges to Providing Palliative Cancer Care-A The-oretical Domains Framework, Pan-Cancer System Survey. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busolo, D.; Woodgate, R. Palliative care experiences of adult cancer patients from ethnocultural groups: A qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2015, 13, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohinata, H.; Aoyama, M.; Miyashita, M. Complexity in the context of palliative care: A systematic review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2022, 11, 3231–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnarajah, A.; Watanabe, S.; Tang, P.A.; Kerba, M.; Tan, A.; Earp, M.; Biondo, P.; Fong, A.; Blacklaws, K.; Bond, C.; et al. The PACES Study: A controlled before and after pragmatic trial of a cancer clinic–based intervention to increase early referral to specialist palliative care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabani, A.; King, S.; Ahmed, S.; Shirt, L.; Slobogian, V.; Vig, C.; Hao, D.; Barbera, L.C.; Kurien, E.; Santana, M.; et al. Patient and caregiver-reported acceptability of an automatic phone call offering supportive and palliative care referral for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, e24097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Sinnarajah, A.; Ahmed, S.; Paolucci, A.; Shirt, L.; Slobogian, V.; Vig, C.; Hao, D.; Barbera, L.C.; Kurien, E.C.; et al. Patient-Rated Acceptability of Automatic Palliative Care Referral: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2025, 69, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Naqvi, S.F.; Sinnarajah, A.; McGhan, G.; Simon, J.; Santana, M. Patient and caregiver experiences with advanced cancer care: A qualitative study informing the development of an early palliative care pathway. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2020, 14, e790–e797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.E.; Ostrove, J.M. Socioeconomic Status and Health: What We Know and What We Don’t. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 896, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebo, P. How well does NamSor perform in predicting the country of origin and ethnicity of individuals based on their first and last names? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebo, P. Are Accuracy Parameters Useful for Improving the Performance of Gender Detection Tools? A Comparative Study with Western and Chinese Names. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 4024–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Naik, N.Y.; Teo, M. Race, Discrimination, and Hedge Funds. (30 March 2022). Available online: https://afajof.org/management/viewp.php?n=15680 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Raymond, G. A deprivation index for health planning in Canada. Chronic Dis. Can. 2009, 29, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P. A comparison of individual and area-based socio-economic data for monitoring social inequalities in health. Health Rep. 2009, 20, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Simpson, A.; Philibert, M.D. Validation of a deprivation index for public health: A complex exercise illustrated by the Quebec index. Chronic Dis. Can. 2014, 34, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamache, P.; Hamel, D.; Blaser, C. Material and Social Deprivation Index: A Summary: Overview of the Methodology; INSPQ: Québec, QC, Canada; BiESP: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Philibert, M.D.; Raymond, G.; Simpson, A. An area-based material and social deprivation index for public health in Québec and Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2012, 103 (Suppl. S2), S17–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, H.P. Poverty, Culture, and Social Injustice: Determinants of Cancer Disparities. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2004, 54, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houttekier, D.; Cohen, J.; Bilsen, J.; Deboosere, P.; Verduyckt, P.; Deliens, L. Determinants of the Place of Death in the Brussels Metropolitan Region. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2009, 37, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, C.; Todd, C.; Caress, A.; Chew-Graham, C. Patterns of Access to Community Palliative Care Services: A Literature Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2009, 37, 884–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.G.; Bowles, K.H.; King, L.; A Luth, E. Why Is Community-Based Palliative Care Declined? Older Adult, Caregiver, and Provider Perspectives. J. Palliat. Med. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.; Hoerger, M.; Norton, S.A.; Guancial, E.; Epstein, R.M.; Duberstein, P.R. Preference for Palliative Care in Cancer Patients: Are Men and Women Alike? J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, 1–6.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gómez, M.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Benítez-Hidalgo, V. Age- and gender-based social inequalities in palliative care for cancer patients: A systematic literature review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1421940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaro, M.; The ISDOC Study Group; Costantini, M.; Merlo, D.F. Inequity in the provision of and access to palliative care for cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC). BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solloway, M.; Lafrance, S.; Bakitas, M.; Gerken, M. A Chart Review of Seven Hundred Eighty-Two Deaths in Hospitals, Nursing Homes, and Hospice/Home Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2005, 8, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.L.; Kaplan, H.B. Gender, social roles and health care utilization. Appl. Behav. Sci. Rev. 1995, 3, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.E.; Anisimowicz, Y.; Miedema, B.; Hogg, W.; Wodchis, W.P.; Aubrey-Bassler, K. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: A QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballering, A.V.; Hartman, T.C.O.; Verheij, R.; Rosmalen, J.G.M. Sex and gender differences in primary care help-seeking for common somatic symptoms: A longitudinal study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2023, 41, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraballo, C.; Ndumele, C.D.; Roy, B.; Lu, Y.; Riley, C.; Herrin, J.; Krumholz, H.M. Trends in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Barriers to Timely Medical Care Among Adults in the US, 1999 to 2018. JAMA Health Forum 2022, 3, e223856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.J.; Clark, D.; Gatrell, A.C. Equity of access to adult hospice inpatient care within north-west England. Palliat. Med. 2004, 18, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A. Measuring Socioeconomic Disparities in Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Qubahan Acad. J. 2025, 5, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locher, J.L.; Kilgore, M.L.; Morrisey, M.A.; Ritchie, C.S. Patterns and Predictors of Home Health and Hospice Use by Older Adults with Cancer. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Sellick, K. Quality of life of cancer patients receiving inpatient and home-based palliative care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 53, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackan, N.A.; Ostir, G.V.; Freeman, J.L.; Mahnken, J.D.; Goodwin, J.S. Decreasing Variation in the Use of Hospice Among Older Adults With Breast, Colorectal, Lung, and Prostate Cancer. Med. Care 2004, 42, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adsersen, M.; Thygesen, L.C.; Neergaard, M.A.; Jensen, A.B.; Sjøgren, P.; Damkier, A.; Clausen, L.M.; Groenvold, M. Cohabitation Status Influenced Admittance to Specialized Palliative Care for Cancer Patients: A Nationwide Study from the Danish Palliative Care Database. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachterman, M.W.; Sommers, B.D. The Impact of Gender and Marital Status on End-of-Life Care: Evidence from the National Mortality Follow-Back Survey. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.A.; D’SOuza, A.G.; Saini, V.; Tang, K.; Quan, H.; Eastwood, C.A. Extracting social determinants of health from inpatient electronic medical records using natural language processing. J. Epidemiol. Popul. Health 2024, 72, 202791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.D.; Eissa, A.; Kiran, T.; Mashford-Pringle, A.; Needham, A.; Dhalla, I. Considerations for collecting data on race and Indigenous identity during health card renewal across Canadian jurisdictions. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2023, 195, E880–E882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’NEill, J.; Tabish, H.; Welch, V.; Petticrew, M.; Pottie, K.; Clarke, M.; Evans, T.; Pardo, J.P.; Waters, E.; White, H.; et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: Using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.; Luth, E.A.; Lin, S.-Y.; Brody, A.A. Advance Care Planning, Palliative Care, and End-of-life Care Interventions for Racial and Ethnic Underrepresented Groups: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, e248–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Outcome | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consult Booked | Declined/Unreachable | Not Called | |||

| Gender | 0.09 | ||||

| Female | 32 (55%) | 10 (36%) | 9 (33%) | ||

| Male | 26 (45%) | 18 (64%) | 18 (67%) | ||

| Age | 0.01 * | ||||

| Under 65 | 23 (40%) | 12 (43%) | 3 (11%) | ||

| 65 and Over | 35 (60%) | 16 (57%) | 24 (89%) | ||

| Immigration Status | 0.48 | ||||

| Canadian | 34 (59%) | 19 (68%) | 12 (44%) | ||

| Not Canadian | 17 (29%) | 7 (25%) | 10 (37%) | ||

| n/a | 7 (12%) | 2 (7%) | 5 (19%) | ||

| Living Arrangements | 0.53 | ||||

| Partner | 38 (66%) | 18 (64%) | 12 (44%) | ||

| Non-partner | 5 (9%) | 1 (4%) | 4 (14) | ||

| Alone | 12 (21%) | 7 (25%) | 9 (33%) | ||

| n/a | 3 (5%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.78 | ||||

| Europe | 44 (76%) | 20 (71%) | 21 (78%) | ||

| Asia | 8 (14%) | 6 (21%) | 5 (18%) | ||

| Africa | 6 (10%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | ||

| Deprivation Index | 0.74 | ||||

| Most deprived | 5 (9%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | ||

| Neutral | 33 (57%) | 17 (61%) | 14 (52%) | ||

| Least Deprived | 8 (14%) | 4 (14%) | 8 (30%) | ||

| Unknown | 12 (21%) | 5 (18%) | 4 (15%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halperin, H.; Akude, P.; King, S.; Biondo, P.; Sinnarajah, A.; Hao, D.; Simon, J. Assessing Disparities in Who Accepts an Early Palliative Care Consultation. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32090485

Halperin H, Akude P, King S, Biondo P, Sinnarajah A, Hao D, Simon J. Assessing Disparities in Who Accepts an Early Palliative Care Consultation. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(9):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32090485

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalperin, Heather, Philip Akude, Seema King, Patricia Biondo, Aynharan Sinnarajah, Desiree Hao, and Jessica Simon. 2025. "Assessing Disparities in Who Accepts an Early Palliative Care Consultation" Current Oncology 32, no. 9: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32090485

APA StyleHalperin, H., Akude, P., King, S., Biondo, P., Sinnarajah, A., Hao, D., & Simon, J. (2025). Assessing Disparities in Who Accepts an Early Palliative Care Consultation. Current Oncology, 32(9), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32090485