Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade: A Framework for Monitoring Uptake and Retention Along the Screening and Treatment Pathway

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade Development

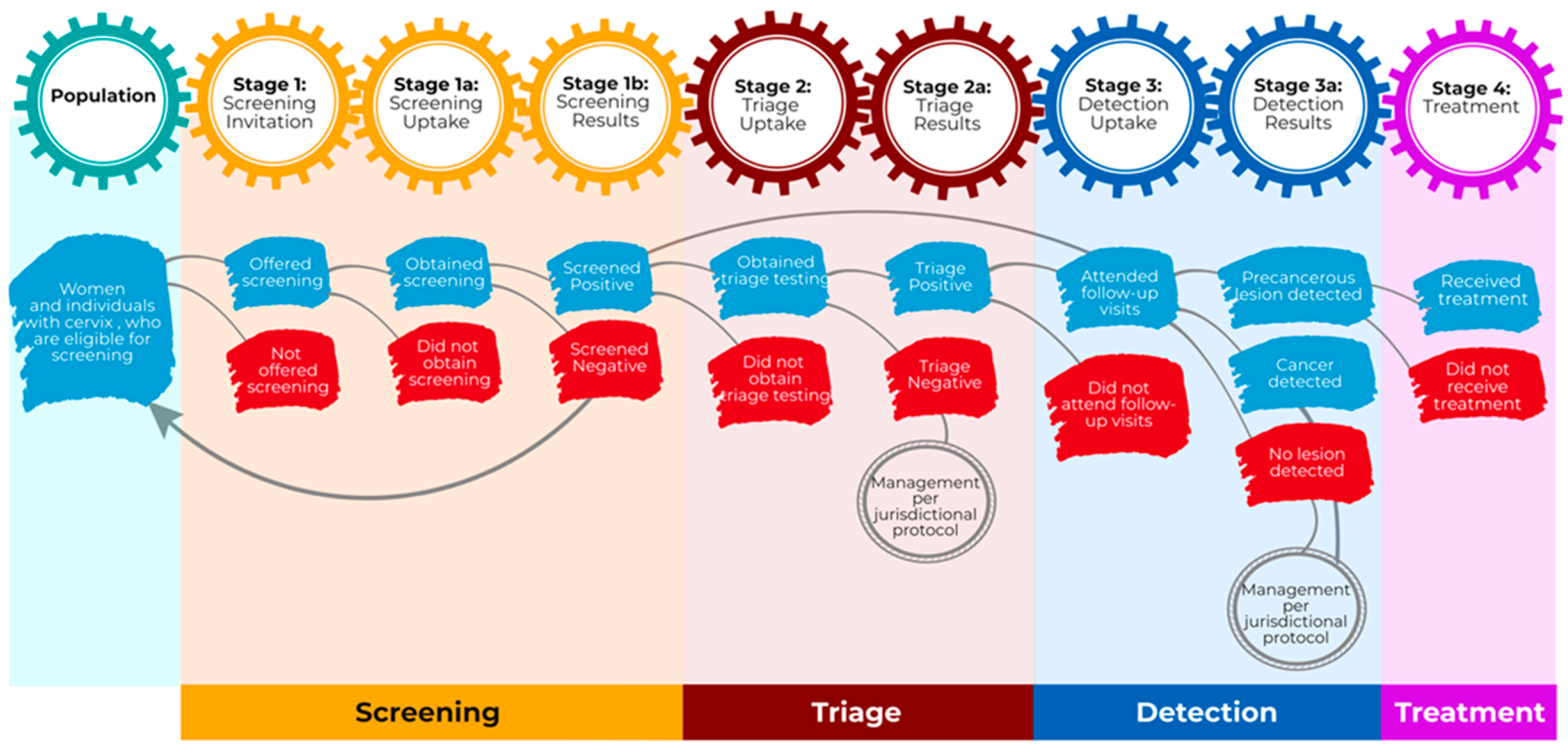

3. Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade Stages

3.1. Population of Interest

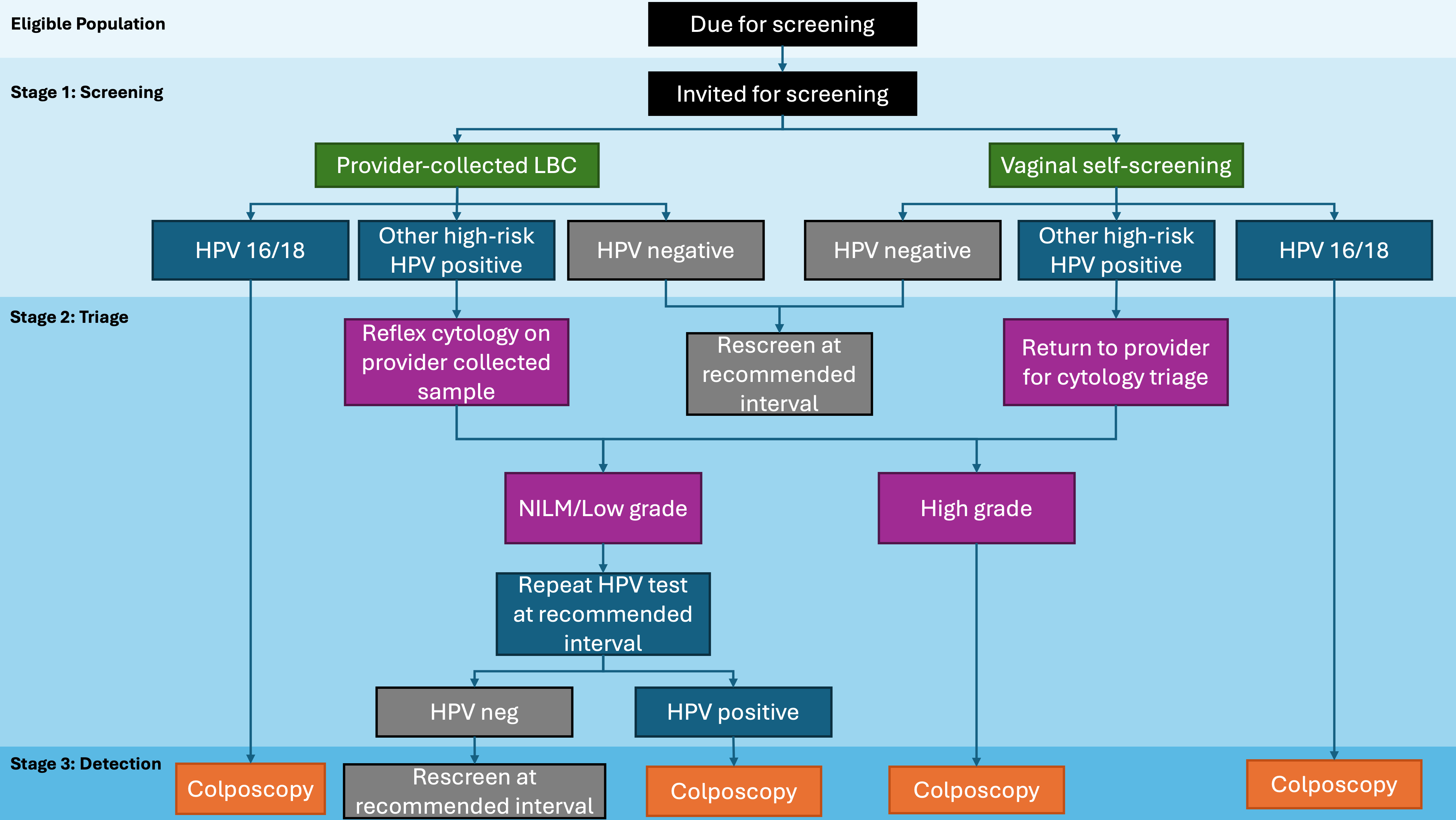

3.2. Screening

3.2.1. Stage 1: Screening Invitation

3.2.2. Stage 1a: Screening Uptake

3.2.3. Stage 1b: Screening Results

3.3. Triage

3.3.1. Stage 2: Triage Uptake

3.3.2. Stage 2a: Triage Results

3.4. Detection

3.4.1. Stage 3: Detection Uptake

3.4.2. Stage 3a: Detection Results

3.5. Treatment

Stage 4: Treatment Uptake

4. Practical Steps for Using the Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade

- Identify the Population:

- •

- Define the eligible group for cervical cancer screening (e.g., age range, risk factors, or geographic location).

- •

- Ensure you have access to data on the number of eligible WIC and the corresponding stages of their care.

- Map Data onto the Cascade Stages:

- •

- Break down the screening algorithm and categorize available data into the four key stages of the Cascade:

- i.

- Screening: Number of WIC invited, participating, and screened.

- ii.

- Triage: Individuals completing triage testing after an abnormal result, and number of those with positive triage results.

- iii.

- Detection: Individuals undergoing follow-up diagnostic testing, and number diagnosed with precancerous lesions.

- iv.

- Treatment: Number receiving appropriate treatment.

- •

- Identify gaps in data or data collection system at each stage and identify strategies to address them.

- Calculate Key Metrics:

- •

- Use program data to calculate the corresponding measures at each stage of the Cascade. Example: screening participation rate = (number screened ÷ eligible population) × 100

- •

- Calculate the attrition rate or loss to follow-up rate at each stage. Example: triage attrition rate = 1—triage completion rate

- Compare Metrics with Targets:

- •

- Assess whether the calculated metrics meet established benchmarks (e.g., WHO targets of 70% screening participation and 90% treatment rates).

- •

- Identify any deviations from the targets and determine potential areas for improvement.

- Identify Attrition Points:

- •

- Look for stages where the largest attrition or loss to follow-up occurs (e.g., WIC who test positive but do not proceed to triage).

- •

- If needed, conduct a more granular-level or stratified analysis to gather more insight.

- •

- Analyze reasons for attrition, such as lack of accessibility, awareness, or follow-up mechanisms.

- Implement Targeted Interventions:

- •

- Develop strategies to address gaps identified at each stage.

- •

- Example: If triage completion rates are low, consider introducing automated reminders or mobile diagnostic units to improve access.

- Monitor Progress over Time:

- •

- Use the Cascade framework longitudinally to track program improvements and the impact of interventions.

- •

- Compare data across different years or regions to identify trends and share best practices.

5. Discussion

- A guiding framework for emerging programs: Screening programs in developmental stages or those undergoing transitions, such as the shift from cytology to HPV screening, can utilize this cascade to embed clearly defined touchpoints with automated data capture through integration with electronic health records or laboratory information systems. The framework supports the development of robust data collection and reporting infrastructures, essential for optimizing program effectiveness.

- A standardized evaluation and benchmarking tool: The cascade provides a consistent and systematic approach for collecting and reporting metrics across key stages of screening. By adopting this standardized framework, existing programs can better evaluate and report their performance, facilitate cross-program comparisons, and share insights and best practices to collectively advance cervical cancer prevention efforts.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cervical Cancer. World Health Organization, 2024. March. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer (accessed on 11 July 2025 ).

- Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- World Health Organization. Improving Data for Decision-Making: A Toolkit for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Programmes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514255 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Action Plan for the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in Canada 2020–2030; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://s22438.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Elimination-cervical-cancer-action-plan-EN.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- The American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team. The American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Prevention and Early Detection of Cervical Cancer 2021. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines.html (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Olthof, E.M.G.; Aitken, C.A.; Siebers, A.G.; van Kemenade, F.J.; de Kok, I. The Impact of Loss to Follow-up in the Dutch Organised HPV-based Cervical Cancer Screening Programme. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 154, 2132–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, E.A.; Kim, J.J. The Value of Improving Failures within a Cervical Cancer Screening Program: An Example from Norway. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Campos, N.G.; Sy, S.; Burger, E.A.; Cuzick, J.; Castle, P.E.; Hunt, W.C.; Waxman, A.; Wheeler, C.M. Inefficiencies and High-Value Improvements in U.S. Cervical Cancer Screening Practice. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 163, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.T.; Sonne, S.B.; Pedersen, H.; Andreasen, E.K.; Serizawa, R.; Ejegod, D.M.; Bonde, J. Participation and relative cost of attendance by direct-mail compared to opt-in invitation strategy for HPV self-sampling targeting cervical screening non-attenders: A large-scale, randomized, pragmatic study. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 156, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Smith, S.B.; Temin, S.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: Updated meta-analyses. BMJ 2018, 363, k4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maver, P.J.; Poljak, M. Primary HPV-Based Cervical Cancer Screening in Europe: Implementation Status, Challenges, and Future Plans. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.-S.; Clark, M.; Carson, E.; Weeks, L.; Moulton, K.; McFaul, S.; McLauchlin, C.M.; Tsoi, B.; Majid, U.; Kandasamy, S. HPV Testing for Primary Cervical Cancer Screening: A Health Technology Assessment; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019.

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Cervical Screening in Canada, 2023–2024. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/cervical-screening-canada-2023-2024/summary/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Wentzensen, N.; Schiffman, M. HPV-Based Cervical Cancer Screening in US. HPV World, The Newsletter on HPV 2018. Available online: https://www.hpvworld.com/articles/hpv-based-cervical-cancer-screening-and-management-of-abnormal-screening-results-in-the-us/#:~:text=Cervical%20cancer%20screening%20and%20management%20is%20undergoing%20a%20transition%20phase,e.g.%20cytology%20to%20HPV%20testing (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Costa, S.; Verberckmoes, B.; Castle, P.E.; Arbyn, M. Offering HPV self-sampling kits: An updated meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies to increase participation in cervical cancer screening. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.W.; Deats, K.; Gambell, J.; Lawrence, A.; Lei, J.; Lyons, M.; North, B.; Parmar, D.; Patel, H.; Waller, J.; et al. Opportunistic offering of self-sampling to non-attenders within the English cervical screening programme: A pragmatic, multicentre, implementation feasibility trial with randomly allocated cluster intervention start dates (YouScreen). E Clin. Med. 2024, 73, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, P.; Innes, C.; Bell, R.; Nip, J.; McMenamin, J.; McBain, L.; Hudson, B.; Gibson, M.; Whaiti, S.T.; Tino, A.; et al. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Screening With Universal Access to Vaginal Self-Testing: Outcomes of an Implementation Trial. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 132, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Hawkes, D.; Sweeney, D.; Wyatt, K.; Nightingale, C.; Chalmers, C.; Saville, S. Exponential uptake of HPV self-collected cervical screening testing 2 years since universal availability in Victoria, Australia. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, R.E.; Izadi-Najafabadi, S.; Smith, L.W.; Gottschlich, A.; Ionescu, D.; Proctor, L.; Ogilvie, G.S.; Peacock, S. Strategies to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer in British Columbia, Canada: A modelling study. CMAJ 2024, 196, E716–E723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, E.A.; Smith, M.A.; Killen, J.; Sy, S.; Simms, K.T.; Canfell, K.; Kim, J.J. Projected time to elimination of cervical cancer in the USA: A comparative modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e213–e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portnoy, A.; Pedersen, K.; Trogstad, L.; Hansen, B.T.; Feiring, B.; Laake, I.; Smith, M.A.; Sy, S.; Nygård, M.; Kim, J.J.; et al. Impact and cost-effectiveness of strategies to accelerate cervical cancer elimination: A model-based analysis. Prev. Med. 2021, 144, 106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, K.; Mandiriri, A.; Shamu, T.; Rohner, E.; Bütikofer, L.; Asangbeh, S.; Magure, T.; Chimbetete, C.; Egger, M.; Pascoe, M. Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade for Women Living with HIV: A Cohort Study from Zimbabwe. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, E.; Mulongo, M.; Pasipamire, T.; Oberlin, A.M.; Goeieman, B.; Williams, S.; Lubeya, M.K.; Rahangdale, L.; Chibwesha, C.J. Mapping the Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade among Women Living with HIV in Johannesburg, South Africaa. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 152, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-X.; Wu, J.-L.; Zheng, R.-M.; Xiong, W.-Y.; Chen, J.-Y.; Ma, L.; Luo, X.-M. A Preliminary Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade for Eight Provinces Rural Chinese Women: A Descriptive Analysis of Cervical Cancer Screening Cases in a 3-Stage Framework. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; MacDuffie, E.; Nsingo, M.; Lei, X.; Mehta, P.; Davey, S.; Urusaro, S.; Chiyapo, S.; Vuylsteke, P.; Monare, B. Benchmarking of the Cervical Cancer Care Cascade and Survival Outcomes After Radiation Treatment in a Low-and Middle-Income Country Setting. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2023, 9, e2200397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.; Juarez, M.; Sacuj, N.; Tzurec, E.; Larson, K.; Miller, A.; Rohloff, P. Loss to Follow-Up and the Care Cascade for Cervical Cancer Care in Rural Guatemala: A Cross-Sectional Study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2022, 8, e2100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Section 3: Patient and Programme Monitoring. In Improving Data for Decision-Making: A Toolkit for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Programmes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysostomou, A.C.; Stylianou, D.C.; Constantinidou, A.; Kostrikis, L.G. Cervical Cancer Screening Programs in Europe: The Transition Towards HPV Vaccination and Population-Based HPV Testing. Viruses 2018, 10, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhn, P.; Wentzensen, N. HPV-Based Tests for Cervical Cancer Screening and Management of Cervical Disease. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol. Rep. 2013, 2, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D. Chapter 14: Role of Triage Testing in Cervical Cancer Screening. JNCI Monogr. 2003, 2003, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doubeni, C.A.; Gabler, N.B.; Wheeler, C.M.; McCarthy, A.M.; Castle, P.E.; Halm, E.A.; Schnall, M.D.; Skinner, C.S.; Tosteson, A.N.; Weaver, D.L. Timely Follow-up of Positive Cancer Screening Results: A Systematic Review and Recommendations from the PROSPR Consortium. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, P.; Taghavi, K.; Hu, S.-Y.; Mogri, S.; Joshi, S. Management of Cervical Premalignant Lesions. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2018, 42, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Lines represent the anticipated flow between stages in the cascade of a cervical cancer screening program and indicate that the proportion of patients in a given stage is calculated from the number of patients in the preceding stage with available data.

Lines represent the anticipated flow between stages in the cascade of a cervical cancer screening program and indicate that the proportion of patients in a given stage is calculated from the number of patients in the preceding stage with available data.  Arrows denote a return to the main population pool.

Arrows denote a return to the main population pool.

Lines represent the anticipated flow between stages in the cascade of a cervical cancer screening program and indicate that the proportion of patients in a given stage is calculated from the number of patients in the preceding stage with available data.

Lines represent the anticipated flow between stages in the cascade of a cervical cancer screening program and indicate that the proportion of patients in a given stage is calculated from the number of patients in the preceding stage with available data.  Arrows denote a return to the main population pool.

Arrows denote a return to the main population pool.

| Study | Target Population | Age Range | Primary Screening Method | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grover et al. (2023) [25] | Women receiving radiation therapy in Botswana | ≥27 years | Not specified | Treatment delay Survival rates |

| Taghavi et al. (2022) [22] | Women living with HIV in Zimbabwe | ≥18 years | Visual inspection with acetic acid and cervicography (VIAC) | Screening uptake Screening result Treatment uptake Rescreening uptake Rescreening results |

| Garcia et al. (2022) [26] | Women in rural Guatemala | 21–65 years | Cytology | Screening uptake Screening result Triage + Detection uptake Treatment uptake |

| Rohner et al. (2021) [23] | Women living with HIV in South Africa | ≥18 years | Cytology/ Pap smear | Screening Results Follow-up uptake Treatment uptake |

| Wang et al. (2019) [24] | Rural Chinese women | 35–64 years | Cytology/ Pap smear | Screening uptake Screening results Detection uptake Detection result |

| Stage | Measure | Numerator | Denominator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | |||

| Stage 1: Screening Invitation | Screening Reach Rate | Number of WIC invited to screen | Eligible WIC: WIC eligible for average risk, routine screening, within eligible screening age range |

| Stage 1a: Screening Uptake | Screening Participation Rate | Number of screened WIC (self-sampled and/or provider-collected) | Number of invited WIC |

| Stage 1b: Screening Results | Screening Positivity Rate | Number of WIC with abnormal results that refer to triage or diagnostic follow-up | Number of screened WIC |

| Triage | |||

| Stage 2: Triage Uptake | Triage Completion Rate | Number of WIC referred to triage who completed all required triage visits | Number of WIC referred to triage |

| Stage 2a: Triage Results | Triage Positivity Rate | Number of WIC with positive triage results | Number of WIC completing triage |

| Detection | |||

| Stage 3: Detection Uptake | Follow-up Completion Rate | Number of WIC completing diagnostic follow-up visits | Number of WIC referred to diagnostic follow-up (directly after primary test or following triage) |

| Stage 3a: Detection Results | Precancer Rate | Number of WIC with precancerous lesions | Number of WIC completing diagnostic follow-up visits |

| Treatment | |||

| Stage 4: Treatment Uptake | Treatment Rate | Number of WIC with detected precancerous lesions who received treatment | Number of WIC with detected precancerous lesions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izadi-Najafabadi, S.; Smith, L.W.; Gottschlich, A.; Booth, A.; Peacock, S.; Ogilvie, G.S. Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade: A Framework for Monitoring Uptake and Retention Along the Screening and Treatment Pathway. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070407

Izadi-Najafabadi S, Smith LW, Gottschlich A, Booth A, Peacock S, Ogilvie GS. Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade: A Framework for Monitoring Uptake and Retention Along the Screening and Treatment Pathway. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(7):407. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070407

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzadi-Najafabadi, Sara, Laurie W. Smith, Anna Gottschlich, Amy Booth, Stuart Peacock, and Gina S. Ogilvie. 2025. "Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade: A Framework for Monitoring Uptake and Retention Along the Screening and Treatment Pathway" Current Oncology 32, no. 7: 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070407

APA StyleIzadi-Najafabadi, S., Smith, L. W., Gottschlich, A., Booth, A., Peacock, S., & Ogilvie, G. S. (2025). Cervical Cancer Screening Cascade: A Framework for Monitoring Uptake and Retention Along the Screening and Treatment Pathway. Current Oncology, 32(7), 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070407