Impact of Oncological Treatment on Quality of Life in Patients with Head and Neck Malignancies: A Systematic Literature Review (2020–2025)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

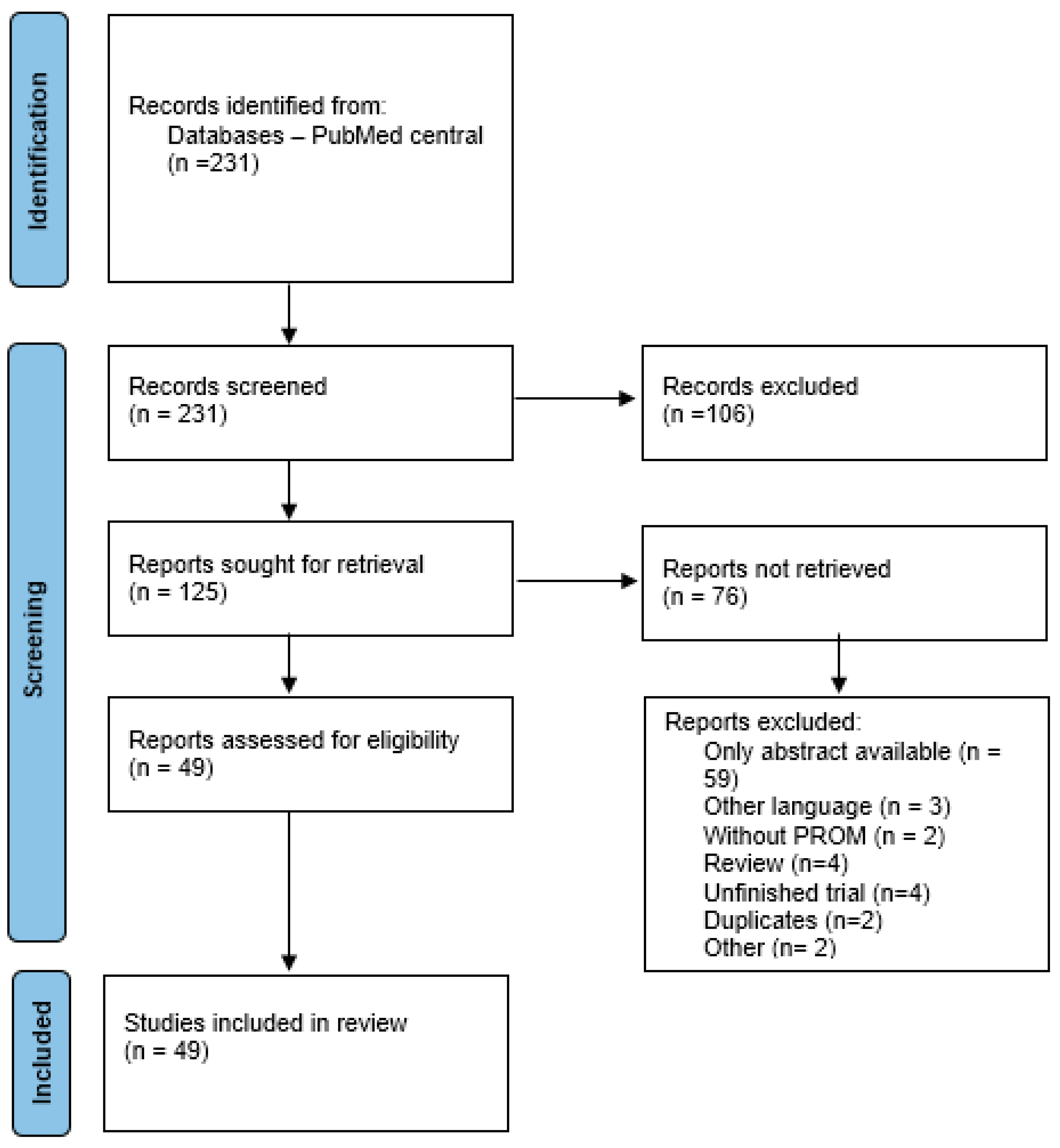

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Methods

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Outcomes and Variables

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis and Presentation

2.6. Effect Measures

2.7. Eligibility for Synthesis

2.8. Handling Missing Data

2.9. Heterogeneity and Sensitivity Analyses

2.10. Risk of Bias Due to Missing Results

2.11. Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Main Results of the Studies

3.2. Main Conclusions of the Studies

3.3. QoL and Functional Outcomes Across Studies: Risk of Bias Assessment

- ✓

- ✓

- ✓

- ✓

- ✓

- ✓

- ✓

- ✓

- Novel Interventions: Nutri-PEITC jelly enhanced progression-free survival and QoL in advanced cases [20].

- ✓

- Most studies were rated very low (31/49) or low (12/49) due to:

- ✓

- ✓

- High certainty was rare, seen in one RCT sub-analysis with low bias and precise estimates [46].

- Research Needs: Larger, randomized trials with standardized measures (e.g., MDADI, EORTC-QLQ) and extended follow-ups are needed [33].

- ➢

- Seven of eight RCTs (Nutting, Lam-Ubol, Hajdú, Karlsson, Jansen, Johansson, Theurer) have some concerns overall, driven by:

- ➢

- Domain 2 (Deviations): Lack of patient blinding in rehabilitation (Hajdú, Karlsson, Jansen, Johansson), surgical/radiation (Nutting, Theurer), or nutritional trials (Lam-Ubol is an exception due to placebo).

- ➢

- Domain 3 (Missing Data): Potential dropout in cancer/rehabilitation trials, except Nutting (phase 3 rigor).

- ➢

- Domain 4 (Outcome Measurement): Subjective outcomes (QoL, swallowing, voice) with unblinded patients, except Lam-Ubol (blinded QoL/PFS).

- ➢

- Xuewei et al. (#44) have a high risk overall, due to high risk in Domains 2 and 4 (no blinding, subjective QoL) and some concerns in Domains 1, 3, and 5, reflecting weaker methodology in acupuncture trials.

- ➢

- Domain 1 (Randomization): Seven RCTs are low risk, indicating robust randomization in high-quality journals (Lancet Oncol, Oral Oncol, Head Neck). Xuewei is an exception (Some concerns).

- ➢

- Domain 5 (Reported Result): Six RCTs are low risk, suggesting protocol adherence, especially in multicenter/phase 3 trials. Xuewei and Johansson have some concerns due to potential unregistered protocols.

- ➢

- Domain 2 (Deviations): Most RCTs (6/8) have some concerns due to impractical blinding in non-pharmacological interventions. Xuewei is high risk (no blinding, analytical issues).

- ➢

- Domain 4 (Outcome Measurement): Six RCTs have some concerns due to subjective outcomes and unblinded patients. Xuewei is high risk (unvalidated QoL). Lam-Ubol is low risk (blinded, objective PFS).

- ➢

- Domain 3 (Missing Data): Seven RCTs have some concerns due to dropout risks in cancer trials. Nutting is low risk (phase 3 rigor).

- ➢

- Non-RCTs: Five studies require NOS or ROBINS-I, not RoB 2, limiting direct comparison with RCTs.

3.4. Implications for Systematic Review

4. Discussion

4.1. Small Sample Size

4.2. Single-Center Study Design

4.3. Limited Generalizability Due to Regional or Population-Specific Factors

4.4. Potential Selection Bias

4.5. Reliance on Self-Reported or Subjective Measures

4.6. Cross-Sectional or Retrospective Design

4.7. Limited Follow-Up Duration

4.8. Missing Data or High Dropout Rates

4.9. Lack of Preoperative or Baseline Data

4.10. Heterogeneity in Treatment or Patient Characteristics

4.11. Specificity of the Inclusion Criteria

4.12. Overall Impact on the Literature Review

- Reliability: Small sample sizes, missing data, and reliance on self-reported measures introduce variability and potential bias, reducing the confidence in reported outcomes. For example, studies like Williamson A et al. (2021) [2] and Aggarwal P et al. (2023) [4] note wider confidence intervals due to small samples, which weakens the precision of QoL or functional outcome estimates.

- Generalizability: Single-center studies and region-specific protocols (e.g., Bozec A et al., 2022 [27]; Goiato MC et al., 2020 [8]) limit the applicability of findings to diverse populations or healthcare settings. This is particularly relevant for your review if you aim to draw conclusions applicable to global or varied clinical contexts.

- Comparability: Heterogeneity in treatment regimens, patient populations, and study designs (e.g., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) makes it challenging to synthesize results or perform meta-analyses. For instance, differences in tumor sites (e.g., oropharynx vs. larynx) and treatment modalities (e.g., TORS vs. RT in Scott SI et al., 2023 [11]) complicate direct comparisons.

- Long-Term Insights: Limited follow-up durations and lack of preoperative data (e.g., Larson AR et al., 2021 [28]; Jia L et al., 2025 [41]) restrict the understanding of long-term QoL or functional outcomes, which are critical for head and neck cancer patients given the chronic nature of treatment-related morbidities.

5. Conclusions

Implications for Future Research

- Refinement of De-escalation Protocols: Current evidence suggests that de-escalated adjuvant therapy—through reduced radiation doses and adjusted CT regimens—can achieve satisfactory oncologic outcomes while minimizing long-term side effects. Future studies should focus on refining these protocols, evaluating them in larger and more diverse patient groups to confirm safety, efficacy, and sustainability.

- Emphasis on Multidimensional Functional Assessment: Many studies have demonstrated the impact of treatments on swallowing function, voice quality, and HrQoL. Future research must integrate validated PROM alongside objective functional tests (e.g., FEES, V-VST, EP-SHI, HoCoS) to standardize data and enable comparison of results across studies.

- Personalized and Multidisciplinary Approaches: Variability based on factors such as the extent of surgical resection, patient age, socioeconomic status, and psychological stress indicates that a one-size-fits-all strategy is not optimal. Future studies should explore personalized therapies integrating baseline HrQoL assessments, predictive models, and multidisciplinary supportive interventions—including psychological counseling, nutritional support, and dental rehabilitation—to optimize treatment plans tailored to each subgroup.

- Comparative Evaluations of Minimally Invasive Surgical Techniques: Emerging data on robotic-assisted surgery and other minimally invasive techniques suggest significant benefits in functional recovery and complication reduction compared to traditional methods. Future research should conduct direct comparative studies between these new approaches and conventional techniques, emphasizing long-term functional and quality-of-life outcomes.

- Integration of Supportive and Rehabilitation Interventions: The results highlight the critical role of supportive interventions—such as nutritional supplements, vocal rehabilitation programs, and guided self-help exercises—in reducing treatment-associated morbidity. Future research should establish the optimal timing, duration, and combination of these interventions while evaluating their cost-effectiveness and impact on patient recovery.

- Exploration of Dose–Effect Relationships and Toxicity Profiles: A detailed analysis of dose–effect relationships and long-term effects, particularly regarding late toxicities (e.g., trismus, fibrosis, and subclinical swallowing disorders), is necessary. Future studies must investigate the mechanisms underlying these effects and develop strategies or adjuvant therapies to minimize toxicities without compromising tumor control.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, A.; Haywood, M.; Awad, Z. Feasibility of Free Flap Reconstruction Following Salvage Robotic-Assisted Resection of Recurrent and Residual Oropharyngeal Cancer in 3 Patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100 (Suppl. 10), 1113S–1118S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, K.; Van Abel, K.M.; Moore, E.J.; Patel, S.H.; Hinni, M.L.; Chintakuntlawar, A.V.; Graner, D.; Neben-Wittich, M.; Garces, Y.I.; Price, D.L.; et al. Long-Term Toxic Effects, Swallow Function, and Quality of Life on MC1273: A Phase 2 Study of Dose De-escalation for Adjuvant Chemoradiation in Human Papillomavirus-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2022, 114, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, P.; Nader, M.E.; Gidley, P.W.; Pratihar, R.; Jivani, S.; Garden, A.S.; Mott, F.E.; Goepfert, R.P.; Ogboe, C.W.; Charles, C.; et al. Association of hearing loss and tinnitus symptoms with health-related quality of life among long-term oropharyngeal cancer survivors. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wulff, N.B.; Dalton, S.O.; Wessel, I.; Arenaz Búa, B.; Löfhede, H.; Hammerlid, E.; Kjaer, T.K.; Godballe, C.; Kjaergaard, T.; Homøe, P. Health-Related Quality of Life, Dysphagia, Voice Problems, Depression, and Anxiety After Total Laryngectomy. Laryngoscope 2022, 132, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.Y.; Hsu, M.H.; Lee, S.H.; Hsueh, S.W.; Lu, C.H.; Yeh, K.Y.; Wang, H.M.; Chang, J.T.; Hung, Y.S.; Chou, W.C. Impact of pretreatment quality of life on tolerance and survival outcome in head and neck cancer patients undergoing definitive CCRT. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2024, 123, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsten, L.H.A.; Jansen, F.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; Vergeer, M.; Brakenhoff, R.H.; Leemans, C.R.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. The course of health-related quality of life from diagnosis to two years follow-up in patients with oropharyngeal cancer: Does HPV status matter? Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4473–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goiato, M.C.; Amoroso, A.P.; Silva, B.; Dos Santos, E.G.; Caxias, F.P.; Bitencourt, S.B.; Moreno, A.; Dos Santos, D.M. The Impact of Surgery and Radiotherapy on Health-Related Quality of Life of Individuals with Oral and Oropharyngeal Carcinoma and Short-Term Follow up after Treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yifru, T.A.; Kisa, S.; Dinegde, N.G.; Atnafu, N.T. Dysphagia and its impact on the quality of life of head and neck cancer patients: Institution-based cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Álvarez-Marcos, C.; Vicente-Benito, A.; Gayol-Fernández, Á.; Pedregal-Mallo, D.; Sirgo-Rodríguez, P.; Santamarina-Rabanal, L.; Llorente, J.L.; López, F.; Rodrigo, J.P. Voice outcomes in patients with advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer treated with chemo-radiotherapy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2022, 42, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scott, S.I.; Madsen, A.K.Ø.; Rubek, N.; Charabi, B.W.; Wessel, I.; Jensen, C.V.; Friborg, J.; von Buchwald, C. Dysphagia and QoL 3 Years After Treatment of Oropharyngeal Cancer With TORS or Radiotherapy. Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Feng, H.; Liang, Z.; Xu, S.; Qin, G. Analysis of swallowing and voice-related quality of life in patients after supracricoid partial laryngectomy. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cocuzza, S.; Maniaci, A.; Grillo, C.; Ferlito, S.; Spinato, G.; Coco, S.; Merlino, F.; Stilo, G.; Santoro, G.P.; Iannella, G.; et al. Voice-Related Quality of Life in Post-Laryngectomy Rehabilitation: Tracheoesophageal Fistula’s Wellness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guimarães, I.; Sousa, A.R.; Gonçalves, M.F. Speech handicap index: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation in European Portuguese speakers with oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 2021, 46, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaguer, M.; Pinquier, J.; Farinas, J.; Woisard, V. Development of a holistic communication score (HoCoS) in patients treated for oral or oropharyngeal cancer: Preliminary validation. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2023, 58, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Henry, M.; Arnovitz, E.; Frenkiel, S.; Hier, M.; Zeitouni, A.; Kost, K.; Mlynarek, A.; Black, M.; MacDonald, C.; Richardson, K.; et al. Psychosocial outcomes of human papillomavirus (HPV)- and non-HPV-related head and neck cancers: A longitudinal study. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.P.; Dietrich, M.S.; Murphy, B.A.; Deng, J. Factors associated with quality of life among patients with a newly diagnosed oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 66, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Atula, M.; Atula, T.; Aro, K.; Irjala, H.; Halme, E.; Jouppila-Mättö, A.; Koivunen, P.; Wilkman, T.; Mäkitie, A.; Elovainio, M.; et al. Psychosocial factors and patient and healthcare delays in large (class T3-T4) oral, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal carcinomas. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pingili, S.; Ahmed, J.; Sujir, N.; Shenoy, N.; Ongole, R. Evaluation of Malnutrition and Quality of Life in Patients Treated for Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 9936715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lam-Ubol, A.; Sukhaboon, J.; Rasio, W.; Tupwongse, P.; Tangshewinsirikul, T.; Trachootham, D. Nutri-PEITC Jelly Significantly Improves Progression-Free Survival and Quality of Life in Patients with Advanced Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer: A Blinded Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- D’Andréa, G.; Bordenave, L.; Nguyen, F.; Tao, Y.; Paleri, V.; Temam, S.; Moya-Plana, A.; Gorphe, P. A prospective longitudinal study of quality of life in robotic-assisted salvage surgery for oropharyngeal cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.X.; Dong, Y.B.; Lu, C.; Bradley, P.J.; Liu, L.F. Efficacy of Larynx Preservation Surgery and Multimodal Adjuvant Therapy for Hypopharyngeal Cancer: A Case Series Study. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023, 102, NP319–NP326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutting, C.; Finneran, L.; Roe, J.; Sydenham, M.A.; Beasley, M.; Bhide, S.; Boon, C.; Cook, A.; De Winton, E.; Emson, M.; et al. Dysphagia-optimised intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus standard intensity-modulated radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer (DARS): A phase 3, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 868–880, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, e328. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00350-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, R.C.; Kamal, M.; Zaveri, J.; Chambers, M.S.; Gunn, G.B.; Fuller, C.D.; Lai, S.Y.; Mott, F.E.; McMillan, H.; Hutcheson, K.A. Self-Reported Trismus: Prevalence, severity and impact on quality of life in oropharyngeal cancer survivorship: A cross-sectional survey report from a comprehensive cancer center. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Hinte, G.; Sancak, T.; Weijs, W.L.J.; Merkx, M.A.W.; Leijendekkers, R.A.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G.; Takes, R.; Speksnijder, C.M. Effect of elective neck dissection versus sentinel lymph node biopsy on shoulder morbidity and health-related quality of life in patients with oral cavity cancer: A longitudinal comparative cohort study. Oral Oncol. 2021, 122, 105510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, J.E.; Nilsen, M.L.; Gooding, W.E.; Anderson, J.L.; Khan, N.I.; Mady, L.J.; Wasserman-Wincko, T.; Duvvuri, U.; Kim, S.; Ferris, R.L.; et al. factors associated with patient-reported quality of life outcomes after free flap reconstruction of the oral cavity. Oral Oncol. 2021, 123, 105574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bozec, A.; Majoufre, C.; De Boutray, M.; Gal, J.; Chamorey, E.; Roussel, L.M.; Philouze, P.; Testelin, S.; Coninckx, M.; Bach, C.; et al. Oral and oropharyngeal cancer surgery with free-flap reconstruction in the elderly: Factors associated with long-term quality of life, patient needs and concerns. A GETTEC cross-sectional study. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 35, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, A.R.; Han, M.; Webb, K.L.; Ochoa, E.; Stanford-Moore, G.; El-Sayed, I.H.; George, J.R.; Ha, P.K.; Heaton, C.M.; Ryan, W.R. Patient-Reported Outcomes of Split-Thickness Skin Grafts for Floor of Mouth Cancer Reconstruction. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2021, 83, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monte, L.E.F.D.; Simão, I.C.; Reis Junior, J.R.D.; Leal, P.D.C.; Dibai Filho, A.V.; Oliveira, C.M.B.; Moura, E.C.R. Evolution of the quality of life of total laryngectomy patients using electrolarynx. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2024, 70, e20231146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Souza, F.G.R.; Santos, I.C.; Bergmann, A.; Thuler, L.C.S.; Freitas, A.S.; Freitas, E.Q.; Dias, F.L. Quality of life after total laryngectomy: Impact of different vocal rehabilitation methods in a middle income country. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Andreassen, R.; Jönsson, B.; Hadler-Olsen, E. Oral health related quality of life in long-term survivors of head and neck cancer compared to a general population from the seventh Tromsø study. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scott, S.I.; Kathrine Ø Madsen, A.; Rubek, N.; Charabi, B.W.; Wessel, I.; Fredslund Hadjú, S.; Jensen, C.V.; Stephen, S.; Patterson, J.M.; Friborg, J.; et al. Long-term quality of life & functional outcomes after treatment of oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng, J.; Murphy, B.A.; Niermann, K.J.; Sinard, R.J.; Cmelak, A.J.; Rohde, S.L.; Ridner, S.H.; Dietrich, M.S. Validity Testing of the Head and Neck Lymphedema and Fibrosis Symptom Inventory. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2022, 20, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harrowfield, J.; Isenring, E.; Kiss, N.; Laing, E.; Lipson-Smith, R.; Britton, B. The Impact of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OPSCC) on Nutritional Outcomes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramalingam, K.; Yadalam, P.K.; Ramani, P.; Krishna, M.; Hafedh, S.; Badnjević, A.; Cervino, G.; Minervini, G. Light gradient boosting-based prediction of quality of life among oral cancer-treated patients. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Balaji, H.; Aithal, V.U.; Varghese, J.J.; Devaraja, K.; Kumar, A.N.N. Agreement between patient-reported and clinician-rated speech and swallowing outcomes—Understanding the trend in post-operative oral cavity cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2024, 159, 107068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuomi, L.; Karlsson, T. Voice Quality, Function, and Quality of Life for Laryngeal Cancer: A Prospective Longitudinal Study Up to 24 Months Following Radiotherapy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100 (Suppl. 10), 913S–920S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S.N.; Waylen, A.E.; Thomas, S.; Penfold, C.; Pring, M.; Waterboer, T.; Pawlita, M.; Hurley, K.; Ness, A.R. Quality of life, cognitive, physical and emotional function at diagnosis predicts head and neck cancer survival: Analysis of cases from the Head and Neck 5000 study. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 277, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zivkovic, A.; Jotic, A.; Dozic, I.; Randjelovic, S.; Cirkovic, I.; Medic, B.; Milovanovic, J.; Trivić, A.; Korugic, A.; Vukasinović, I.; et al. Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Postoperative Complications and Quality of Life After Laryngeal Cancer Surgery. Cells 2024, 13, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grant, S.R.; Hutcheson, K.A.; Ye, R.; Garden, A.S.; Morrison, W.H.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Brandon Gunn, G.; Fuller, C.D.; Phan, J.; Reddy, J.P.; et al. Prospective longitudinal patient-reported outcomes of swallowing following intensity modulated proton therapy for oropharyngeal cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 148, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jia, L.; Yan, C.; Liu, R.; He, P.; Liu, A.; Yang, F.; Huangfu, H.; Zhang, S. Early application value of flexible laryngoscope swallowing function assessment in patients after partial laryngectomy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aggarwal, P.; Hutcheson, K.A.; Garden, A.S.; Mott, F.E.; Lu, C.; Goepfert, R.P.; Fuller, C.D.; Lai, S.Y.; Gunn, G.B.; Chambers, M.S.; et al. Determinants of patient-reported xerostomia among long-term oropharyngeal cancer survivors. Cancer 2021, 127, 4470–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hajdú, S.F.; Wessel, I.; Dalton, S.O.; Eskildsen, S.J.; Johansen, C. Swallowing Exercise During Head and Neck Cancer Treatment: Results of a Randomized Trial. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, M.; Zong, M.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J. Effect of three tongue needles acupoints Lianquan (CV23) and Hegu (LI4) combined with swallowing training on the quality of life of laryngeal cancer patients with dysphagia after surgery. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2022, 42, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karlsson, T.; Tuomi, L.; Finizia, C. Effect of voice rehabilitation following radiotherapy for laryngeal cancer—A 3-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Acta Oncol. 2022, 61, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, F.; Eerenstein, S.E.J.; Cnossen, I.C.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; de Bree, R.; Doornaert, P.; Halmos, G.B.; Hardillo, J.A.U.; van Hinte, G.; Honings, J.; et al. Effectiveness of a guided self-help exercise program tailored to patients treated with total laryngectomy: Results of a multi-center randomized controlled trial. Oral Oncol. 2020, 103, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, M.; Finizia, C.; Persson, J.; Tuomi, L. Cost-effectiveness analysis of voice rehabilitation for patients with laryngeal cancer: A randomized controlled study. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 5203–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, W.X.; Dong, Y.B.; Lu, C.; Bradley, P.J.; Liu, L.F. Survival and swallowing function outcome impact factors analysis of surgery-oriented comprehensive treatment for hypopharyngeal cancer in a series of 122 patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2022, 101, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theurer, J.A.; Martino, R.; Jovanovic, N.; de Almeida, J.R.; Goldstein, D.P.; Fung, K.; Yoo, J.; MacNeil, S.D.; Winquist, E.; Hammond, J.A.; et al. Impact of Transoral Robotic Surgery Versus Radiation on Swallowing Function in Oropharyngeal Cancer Patients: A Sub-Study From a Randomized Trial. Head Neck 2025, 47, 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nakai, M.Y.; Menezes, M.B.; de Carvalho, J.V.B.G.; Dias, L.P.M.; de Barros Silva, L.A.; Tenório, L.R.; Gonçalves, A.J. Quality of life after Supracricoid Partial Laryngectomy. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 50, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R.S.; Vyas, R.; Mosaddad, S.A.; Heboyan, A. Efficacy of Oral Rehabilitation Techniques in Patients With Oral Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 131, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, A.; Macluskey, M.; Mc Goldrick, N.; Conway, D.I.; Glenny, A.M.; Clarkson, J.E.; Worthington, H.V.; Chan, K.K. Interventions for the treatment of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer: Chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 12, CD006386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Genden, E.M.; Kotz, T.; Tong, C.C.; Smith, C.; Sikora, A.G.; Teng, M.S.; Packer, S.H.; Lawson, W.L.; Kao, J. Transoral robotic resection and reconstruction for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 1668–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, K.A.; Holsinger, F.C.; Kupferman, M.E.; Lewin, J.S. Functional outcomes after TORS for oropharyngeal cancer: A systematic review. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutcheson, K.A.; Warneke, C.L.; Yao, C.M.K.L.; Zaveri, J.; Elgohari, B.E.; Goepfert, R.; Hessel, A.C.; Kupferman, M.E.; Lai, S.Y.; Fuller, C.D.; et al. Dysphagia After Primary Transoral Robotic Surgery With Neck Dissection vs Nonsurgical Therapy in Patients With Lowto Intermediate-Risk Oropharyngeal Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.B.; Hinni, M.L.; Pollei, T.R.; Hayden, R.E.; Moore, E.J. Severe prolonged dysphagia following transoral resection of bilateral synchronous tonsillar carcinoma. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 3585–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.J.; Jackson, A.; Setton, J.; Riaz, N.; McBride, S.; Leeman, J.; Kowalski, A.; Happersett, L.; Lee, N.Y. Modeling Dose Response for Late Dysphagia in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer in the Modern Era of Definitive Chemoradiation. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 2017, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourmand, R.; Olsson, S.E.; Fijany, A. Tracheoesophageal puncture and quality of life after total laryngectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2024, 9, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boyle, K.; Jones, S. Functional outcomes of early laryngeal cancer—Endoscopic laser surgery versus external beam radiotherapy: A systematic review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2022, 136, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banda, K.J.; Chu, H.; Kao, C.C.; Voss, J.; Chiu, H.L.; Chang, P.C.; Chen, R.; Chou, K.R. Swallowing exercises for head and neck cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, C.; Kent, S.; Schache, A.; Rogers, S.; Shaw, R. Health-related quality of life, functional outcomes, and complications after sentinel lymph node biopsy and elective neck dissection in early oral cancer: A systematic review. Head Neck 2023, 45, 2754–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff, N.B.; Højager, A.; Wessel, I.; Dalton, S.O.; Homøe, P. Health-Related Quality of Life Following Total Laryngectomy: A Systematic Review. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Study Type | NO of Studies | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case series | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Clinical trial | 1 | 79 | 79 |

| Cross-sectional study | 15 | 21 | 892 |

| Nationwide prospective questionnaire-based study | 1 | 203 | 203 |

| Prospective study | 19 | 28 | 2171 |

| Randomized controlled trial | 8 | 66 | 240 |

| Retrospective study | 4 | 21 | 122 |

| Sub-study from a randomized trial | 1 | 21 | 21 |

| Survey study | 1 | 33 | 33 |

| Treatment Category | Description (Authors) |

|---|---|

| Surgery | Selective neck dissection, transoral robotic surgery (TORS), total laryngectomy (TL), partial laryngectomy, free-flap reconstruction, supracricoid partial laryngectomy (SCPL), tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) (Williamson A, Wulff NB, Bozec A, Jimenez JE, Larson AR, Monte LEFD, Souza FGR, Atula M, Scott SI, D’Andr’ea G, Goiato MC, van Hinte G, Balaji H, Zivkovic A, Liu T, Cocuzza S, Nakai MY) |

| Radiotherapy (RT) | Adjuvant RT, intensity-modulated RT (IMRT), proton therapy (IMPT), dysphagia-optimized IMRT (DO-IMRT), conventional/hyperfractionated RT (Price K, Aggarwal P, Wulff NB, Alvarez-Marcos C, Pingili S, Cardoso RC, Bozec A, Guimaraes I, Balaguer M, Henry M, Scott SI, Korsten LHA, Tuomi L, Rogers SN, Grant SR, Nutting C, Theurer JA, Karlsson T, Johansson M, Li WX) |

| Chemotherapy (CT) | Concurrent chemoradiation (CRT) with cisplatin, docetaxel, or 5-Fluorouracil, induction chemotherapy, targeted therapy (Price K, Aggarwal P, Alvarez-Marcos C, Pingili S, Cardoso RC, Bozec A, Guimaraes I, Balaguer M, Henry M, Yifru TA, Hung CY, Rogers SN, Grant SR, Li WX) |

| Combination Therapy | Surgery with adjuvant RT/CT, chemoradiation, multimodality treatment (surgery, RT, CT) (Pingili S, Guimaraes I, Balaguer M, Yifru TA, Henry M, Korsten LHA, Andreassen R, Scott SI, Deng J, Harrowfield J, Balaji H, Rogers SN, Li WX) |

| Novel Interventions | Nutri-PEITC Jelly, acupuncture with swallowing training, progressive resistance training (PRT), voice rehabilitation, and swallowing exercises (Lam-Ubol A, Zhu X, Hajd’u SF, Karlsson T, Johansson M, Jia L) |

| No. | |

|---|---|

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) | 17 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer—Head and Neck questionnaire (EORTC-H&N35) | 14 |

| Voice-Related QoL questionnaire (V-RQOL) | 2 |

| M D Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) | 7 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | 5 |

| Functional Outcome Swallowing Scale (FOSS) | 3 |

| Voice Handicap Index-10 (VHI-10) | 4 |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G) | 4 |

| Consensus Protocol for Auditory–Perceptual Voice Assessment (CAPE-V) | 1 |

| Swallowing QoL questionnaire (SWAL-QoL) | 4 |

| Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34) | 1 |

| Neck Dissection Impairment Index (NDII) | 2 |

| Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) | 1 |

| Mandibular Function Impairment Questionnaire (MFIQ) | 1 |

| Head and Neck Lymphedema and Fibrosis Symptom Inventory (HN-LEF SI) | 1 |

| Modified Barium Swallow Study (MBS) | 2 |

| Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS) | 1 |

| Performance Status Scale–Head and Neck (PSS-H&N) | 1 |

| European QoL (EQ-5D) Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Head and Neck (FACT-H&N) | 3 |

| University of Michigan Xerostomia-related QoL Scale (XeQOLS) | 1 |

| Tumor response evaluations Serum p53 and cytochrome c levels (VAG) | 2 |

| Progression-free survival (PFS) measurements | 1 |

| Patient Concerns Inventory (PCI) | 1 |

| Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale (DOSS) | 1 |

| Speech Handicap Index (SHI) | 3 |

| Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ) | 3 |

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM) | 2 |

| MD Anderson Symptom Inventory Head and Neck module (MDASI-HN) | 2 |

| University of Washington QoL(UW-QOL) score | 4 |

| Patient Generated-Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) | 1 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | 1 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) | 1 |

| General Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-2) | 1 |

| Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) EQ-5D | 1 |

| Swedish Self-Evaluation of Communication Experiences After Laryngeal Cancer (S-SECEL) | 2 |

| Oral Impact on Daily Performances questionnaire | 1 |

| Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10) | 1 |

| Neck Disability Index | 2 |

| Dysphagia Handicap Index Kannada (DHI-K) | 1 |

| Symptom Check List | 2 |

| EORTC QLQ H&N43 | 2 |

| Three-Item Loneliness Scale | 1 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | 2 |

| Authors, Year, Region | No. | Evaluation Methods | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Williamson A et al., 2021 United Kingdom | 3 | UW-QOL MDADI | Histopathological analysis verified complete removal of the primary tumor in all instances. Two patients had smooth recoveries, but one experienced a chest infection and tracheocutaneous fistula, treated non-surgically. The average hospital stay was 15 days [2]. |

| Price K et al., 2022 United States | 79 | MBS FOIS PSS-H&N EQ-5D FACT-H&N EORTC QLQ-H&N35 XeQOLS | Low rates of long-term toxic effects. Improved swallowing function by 12 months post-treatment; QoL returned to baseline levels over time. No patients required long-term feeding tube dependence [3]. |

| Aggarwal P et al., 2023 United States | 880 | MDASI-HN | In total, 64.4% of survivors reported mild to severe hearing symptoms. Hearing loss and tinnitus were significantly associated with worse HrQoL. Moderate to severe hearing loss and tinnitus increased the odds of reporting moderate to severe symptom distress [4]. |

| Wulff NB et al., 2022 Denmark and Sweden | 172 | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-H&N35, V-RQOL MDADI, HADS | Participants scored worse than normative reference populations on nearly all scales of the EORTC questionnaires. A total of 46% experienced moderate/severe dysphagia, 57% had moderate/severe voice problems, 16% had depression, and 20% had anxiety. Increasing voice problems, dysphagia, depression, and comorbidities were associated with lower HrQoL [5]. |

| Álvarez-Marcos C et al., 2022 Spain | 21 | EORTC-H&N35, VHI, CAPE-V | Voice changes were frequent, with alterations in all CAPE-V attributes. A total of 78% of patients showed type II and III spectrograms in acoustic analysis. EORTC-H&N35 scores showed a reduction in 10–40% of items related to voice [10]. |

| Pingili S et al., 2021 India | 97 | EORTC QOL-H&N35, MFIQ | Most commonly reported symptoms: xerostomia (93.81%), pain (81.44%), dysphagia (76.3%). In total, 40.2% of patients experienced malnutrition. Malnutrition was lower in patients who had nutritional supplements. QoL deteriorated immediately after treatment but improved over time [19]. |

| Cardoso RC et al., 2021 United States | 892 | MDASI-HN. EQ-5D EuroQol-5D MDADI | In total, 31% of patients reported trismus. Severity of trismus negatively impacted QoL. Trismus correlated with increased dysphagia and dietary restrictions. Patients with severe trismus were more likely to be feeding tube-dependent. Adherence to jaw stretching exercises was associated with lower trismus prevalence [24]. |

| Bozec A et al., 2020 France | 64 | EORTC QLQ-C30, QLQ-H&N35, QLQ-ELD14. HADS. PCI DOSS | Long-term QoL and functional measures remained largely intact. Primary ongoing issues included fatigue, constipation, and oral function difficulties. Salivary dysfunction and challenges with chewing/swallowing were key patient concerns. Significant psychological distress (HADS score ≥ 15) and frailty (G8 score < 15) correlated strongly with reduced QoL [27]. |

| Guimarães I et al., 2021 Portugal | 95 | EP-SHI | The EP-SHI demonstrated strong reliability and validity, distinguishing between patients and healthy individuals. It showed significant correlations with the European Portuguese Voice Handicap Index (EP-VHI) [14]. |

| Balaguer M et al., 2023 France | 25 | ECVB, DIP, PHI, CHI, EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-H&N35 | A holistic communication score (HoCoS) was developed to measure the impact of speech disorders on communication in patients treated for oral or oropharyngeal cancer. The score showed good reliability (rs = 0.91) and validity [15]. |

| Jimenez JE et al., 2021 United States | 80 | EAT-10, UW-QOL NDI, PHQ-2, GAD-2 | The degree of tongue resection was closely linked to diminished quality-of-life outcomes, particularly in patients with oral tongue defects [26]. |

| Larson AR et al., 2021 United States | 24 | UW-QOL 4. | Acceptable QoL outcomes in swallowing and speech; anterior floor of mouth (A-FOM) patients reported worse chewing outcomes compared to lateral floor of mouth (L-FOM) patients [28]. |

| Monte LEFD et al., 2024 Brazil | 31 | UW-QOL. | Significant improvements were observed in domains like speech, pain, appearance, activity, recreation, mood, and anxiety. However, no statistical significance was found for swallowing, chewing, taste, and saliva [29]. |

| Souza FGR et al., 2020 Brazil | 95 | UW-QOL, FACT-HN, EORTC QLQ-H&N35. | Patients using tracheoesophageal prostheses reported superior QoL compared to those relying on electrolarynx or esophageal speech. Lack of vocal output was tied to poorer quality of life [30]. |

| Andreassen R et al., 2022 Norway | 216 | Oral Impact on Daily Performances questionnaire | Survivors of head and neck cancer faced a fourfold higher likelihood of reporting issues with daily activities compared to the general population. Eating and food enjoyment were the most commonly impacted areas [31]. |

| Yifru TA et al., 2021 Ethiopia | 102 | MDADI | The composite mean MDADI score was 53.29, reflecting impaired swallowing-related QoL. Factors such as female gender, low income, advanced tumor stage, and laryngeal cancer were associated with poorer QoL [9]. |

| Atula M 2024 Finland | 203 | SSQ BDI, Three-Item Loneliness Scale. | No association was found between psychosocial factors and patient delay. Patients with large head and neck cancers had lower socioeconomic status and higher depression rates compared to the general Finnish population [18]. |

| Hung CY 2024 Taiwan | 461 | EORTC QLQ-HN35 | Patients with higher QLQ-HN35 scores had an increased risk of incomplete CCRT (13.4% vs. 6.5%, OR = 2.22, p = 0.015). Higher scores were associated with more emergency room visits (36.4% vs. 27.0%, OR = 1.55, p = 0.030) and unexpected hospitalizations (33.8% vs. 19.6%, OR = 2.10, p = 0.001). Higher scores correlated with increased grade 3 hematological (34.2% vs. 21.3%, OR = 1.92, p = 0.002) and non-hematological toxicities (78.8% vs. 68.7%, OR = 1.69, p = 0.014). Lower QLQ-HN35 scores were linked to better overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) [6]. |

| Henry M et al., 2022 Canada | 146 | HADS, FACT-G + Head and Neck Module, SCNS-SF34 | HPV-negative patients had higher anxiety and depression levels immediately post-diagnosis. HPV-positive patients showed lower psychological distress but had increased vulnerability post-treatment. Major depressive disorder (MDD) significantly impacted anxiety, depression, and QoL in HPV-positive patients [16]. |

| Scott SI et al., 2021 United States | 44 | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-HN35 MDADI, NDII, OSS | Salivary flow rates dropped significantly in the RT group at 12 months. The RT group also showed the largest declines in QoL scores related to dry mouth and sticky saliva. Swallowing function worsened in both groups at 12 months, while shoulder impairment was uncommon in both [32]. |

| D’Andréa G et al., 2022 France | 53 | MDADI, EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-H&N35 | MDADI total scores at preoperative, 1-year, and 2-year marks were 71.4, 64.3, and 57.5, respectively. QLQ-C30 global scores at the same intervals were 61.2, 59.4, and 80.6. Decannulation was achieved in 97.1% of tracheotomized patients. Two-year enteral tube dependency was 23.1%. Two-year overall survival, disease-free survival, and local control rates were 59%, 46.1%, and 80.9%, respectively [21]. |

| Andersen LP et al., 2023 United States | 115 | EORTC QLQ-C30, HADS, BHLS | Median global HrQoL score was 67.7 (IQR = 50.0, 83.4). Anxiety and depression were significantly inversely correlated with QoL. Higher income and early-stage cancer were associated with better physical functioning [17]. |

| Korsten LHA et al., 2021 Netherlands | 270 | (EORTC QLQ-C30) (EORTC QLQ-HN35) | Patients with HPV-positive tumors had better QoL before treatment, worsened more during treatment, but recovered better and faster at follow-up. Differences in global quality of life, physical, role, and social functioning, fatigue, pain, insomnia, and appetite loss were observed between HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients. Oral pain followed a different trajectory, with HPV-positive patients reporting lower pain before treatment and at certain follow-up points [7]. |

| Goiato MC et al., 2020 Brazil | 50 | EORTC QLQ-C30 EORTC QLQ-HN35 | QoL was significantly affected by treatment type and tumor location. Patients treated with surgery plus RT had worse QoL scores compared to those treated with surgery alone. The period of greatest morbidity was 1 week after treatment. QoL scores improved over time, with many returning to baseline levels after 3 months [8]. |

| Scott SI et al., 2023 Denmark | 44 | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-HN35, MDADI | Significant improvement in swallowing function from 1 to 3 years post-treatment. The TORS group showed better safety scores and swallowing efficiency. QoL improvements were noted only in TORS-treated patients. The RT group showed deterioration in QoL scores despite functional improvements [32]. |

| Deng J et al., 2022 United States | 117 | HN-LEF SI, VHNSS, EORTC QLQ-C30 HADS, SF-MPQ, NDI. | The study validated the HN-LEF SI by demonstrating expected correlations with existing quality-of-life and symptom burden measures, confirming its construct validity [33]. |

| Harrowfield J et al., 2021 Australia | 83 | PG-SGA, PHQ-9, EORTC QLQ-C30. | HPV-positive patients were more likely to experience > 10% weight loss three months post-treatment. No notable difference in malnutrition rates was observed between HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients during treatment [34]. |

| Ramalingam K et al., 2024 India | 111 | EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-HN43. | Light gradient boosting predicted cancer patients’ QoL with 96% accuracy and 0.20 log loss [35]. |

| van Hinte G et al., 2021 Netherlands | 69 | SDQ, SPADI, EQ-5D, EORTC-QLQ-HN35. | SLNB patients had better short-term shoulder function compared to END patients; no significant differences in long-term health-related quality of life [25]. |

| Balaji H et al., 2024 India | 53 | SHI-K DHI-K. | Poor agreement between clinician-rated and patient-reported outcomes for speech and swallowing (ICC values: 0.480 for speech, 0.471 for swallowing) [36]. |

| Tuomi L et al., 2021 Sweden | 28 | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-H&N35, S-SECEL | No significant changes in HrQoL perceptual voice quality over 24 months post-RT. However, HrQoL scores remained inferior to those of healthy controls, with significant deterioration in dry mouth and sticky saliva [37]. |

| Rogers SN et al., 2020 United Kingdom | 2171 | EORTC QLQ-C30 | Higher baseline HrQoL scores were associated with improved survival rates across most tumor sites. Specific functional domains like physical, role, and social functioning showed significant associations with survival [38]. |

| Zivkovic A et al., 2024 Serbia | 56 | EORTC QLQ-H&N43 | Significant predictors of QoL included T stage, pain intensity, and extent of surgical procedure. Oxidative stress markers (SOD, MDA) were linked to postoperative complications [39]. |

| Grant SR et al., 2020 United States | 71 | MDADI | Swallowing function declined sharply during treatment but showed rapid recovery by 10 weeks post-treatment, with steady improvement through two years [40]. |

| Jia L et al., 2025 China. | 30 | MDADI, FEES, VFSS. | FEES showed high sensitivity (84%) and specificity (94%) for detecting aspiration. MDADI scores indicated significant swallowing difficulties post-surgery, with improvements over time [41]. |

| Nutting C et al., 2023 United Kingdom and Ireland | 112 | MDADI | Patients in the DO-IMRT group had significantly higher MDADI composite scores at 12 months compared to the standard IMRT group (mean score 77.7 vs. 70.6, p = 0.037). DO-IMRT led to lower radiation doses to the pharyngeal constrictor muscles. Serious adverse events were reported in 23 patients, with common late adverse events, including hearing impairment, dry mouth, and dysphagia [23]. |

| Lam-Ubol A et al., 2023 Thailand | 72 | HrQoL assessments, PFS measurements, Tumor response evaluations, Serum p53 and cytochrome c levels | The study group showed improved HrQoL and stable disease compared to the control group. Progression-free survival was significantly longer in the study group. Serum p53 levels increased in the study group, suggesting potential p53 reactivation. No serious intervention-related adverse events occurred [20]. |

| Aggarwal P et al., 2021 Netherlands | 92 | SWAL-QOL. SHI SDQ. EORTC QLQ-C30 & QLQ-H&N35 PAM | Patients in the intervention group reported fewer swallowing and communication problems over time. No significant differences were found in speech, shoulder problems, patient activation, or overall quality of life. Patients within 6 months post-surgery benefited most from the intervention [42]. |

| Hajdú SF et al., 2022 Denmark | 240 | EORTC QLQ C-30, EORTC QLQ-H&N35, MD MDADI NRS. MDI SCL-92 Anxiety subscale. | Significant improvements in mouth opening, QoL, depression, and anxiety at 12 months in the intervention group compared to non-active controls. No significant effect on swallowing safety [43]. |

| Zhu X et al., 2022 China | 71 | VFSE MDADI, QLQ-C30 | The experimental group showed significantly higher effective rates (97.1%) and complete remission rates (36.1%) compared to the control group (60% and 14.3%, respectively). Improvements in VFSE, MDADI, and QLQ-C30 scores were significantly greater in the experimental group [44]. |

| Karlsson T et al., 2022 Sweden | 74 | S-SECEL, GRBAS protocol grade, Roughness, Breathiness, Asthenia, Strain, Acoustic analysis. | The intervention group showed significant improvements in communication experiences and perceptual voice qualities (breathiness and strain) over three years. The control group demonstrated deterioration in roughness [45]. |

| Jansen F et al., 2020 Netherlands. | 92 | SWAL-QOL SHI, SDQ, EORTC QLQ-C30/H&N35, PAM | The intervention group showed progress in swallowing and communication issues over time compared to the control group. No significant differences were noted for speech, shoulder issues, patient activation, or HrQoL [46]. |

| Johansson M et al., 2020 Sweden | 66 | EORTC QLQ-C30 mapped to EQ-5D values for quality-adjusted life years QALYs. | Voice rehabilitation improved HrQoL and communicative function, preventing deterioration of voice quality over time [47]. |

| Li WX et al., 2023 China | 64 | FOSS, VHI-10 FACT-G | Three-year OS was 60.7%, and five-year OS was 47.3%. Patients with Stage I or II disease had significantly higher OS than those with Stage III or IV. Decannulation succeeded in 85.9% of patients, and 78.1% achieved satisfactory swallowing function. The median FACT-G quality-of-life score was 75 [22]. |

| Li WX et al., 2022 China | 122 | FOSS, FACT-G | Five-year OS and disease-free survival (DFS) were 40.0% and 36.1%, respectively. Swallowing function was satisfactory in 73.8% of patients. Tracheostomy-free survival was achieved in 45.1% of patients. Local–regional recurrence and distant metastasis were independent impact factors for OS and DFS [48]. |

| Liu T et al., 2024 China | 21 | MDADI VHI-10. | Patients showed satisfactory recovery in swallowing and voice function. The mean MDADI score was 92.67, indicating good swallowing-related quality of life. The mean VHI-10 score was 7.14, reflecting minimal impact of voice disorders on QoL [12]. |

| Cocuzza S et al., 2020 Italy | 54 | V-RQoL VHI. | Tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis showed better socio-emotional and functional outcomes compared to esophageal speech. However, fistula-related complications negatively impacted quality of life [13]. |

| Theurer JA et al., 2025 Canada | 21 | MDADI, MBSImP, PAS. | Swallowing profiles were not significantly different between treatment arms. Pharyngeal swallowing impairments were weakly associated with MDADI subscales and PAS scores [49]. |

| Nakai MY et al., 2021 Brazil | 33 | EORTC QLQ-C30 and H&N35 | SPL patients scored better in global health status–QoL and general activities, with fewer sensory and speech-related symptoms compared to TL patients [50]. |

| Authors, Year, Region | Tumor Site | Main Conclusion | Study Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Williamson A et al., 2021 United Kingdom | Oropharynx | ORS-assisted resection combined with RFFF reconstruction can achieve good oncological and quality-of-life outcomes with acceptable postoperative complications [2]. | Small sample size, limited follow-up duration, and lack of direct comparison with conventional surgical approaches. |

| Price K et al., 2022 United States | Oropharynx | De-escalated adjuvant therapy resulted in excellent swallow outcomes and preserved QoL. Lower radiation doses reduced long-term toxic effects. Further studies are needed to confirm long-term benefits [3]. | Single-institution study. Limited generalizability due to specific inclusion criteria. Potential selection bias due to exclusion criteria. |

| Aggarwal P et al., 2023 United States | Oropharynx | The research emphasizes the importance of ongoing audiological assessments and monitoring to identify hearing issues early. Prompt intervention may reduce the long-term effects on quality of life [4]. | Small sample sizes led to wider confidence intervals. Variability in treatment regimens and patient selection may have influenced results. |

| Wulff NB et al., 2022 Denmark and Sweden | Hypopharynx and Larynx | A substantial proportion of patients experienced clinically significant late effects, which negatively impacted HrQoL. Voice problems, dysphagia, depression, and anxiety were independently associated with lower HrQoL [5]. | Single-center study, limiting generalizability. Variability in rehabilitation approaches across regions. |

| Álvarez-Marcos C et al., 2022 Spain | Hypopharynx and Larynx | Subclinical voice disorders are common after chemo-RT. Although patients consider vocal impairment minor, it may contribute to reduced quality of life [10]. | Small sample size. Single-center study, limiting generalizability. |

| Pingili S et al., 2021 India | Oral and Oropharynx | Treatment significantly impacts quality of life, but recovery improves symptoms over time. Nutritional supplements play a crucial role in reducing malnutrition [19]. | Single-center study, limiting generalizability. Modified questionnaires to suit the Indian population. Small sample size. |

| Cardoso RC et al., 2021 United States | Oral and Oropharynx | Trismus is a prevalent and impactful morbidity in long-term oropharyngeal cancer survivorship. Advanced disease stages, tumor sub-site (tonsil), and CCT were associated with increased trismus prevalence. Further investigation is needed to explore dose–effect relationships on muscles of mastication [24]. | Self-reported trismus assessment may introduce bias. Limited generalizability due to single-institution study. Potential selection bias due to exclusion criteria. Small sample size for certain subgroups (IMPT and PORT patients). |

| Bozec A et al., 2022 France | Oropharynx | An inverse relationship was observed between patient concerns and quality of life. Dental restoration, psychological care, and nutritional support are essential for managing elderly OOPC patients [27]. | Limited generalizability due to France-specific treatment protocols. Small sample size. Potential selection bias due to exclusion criteria. |

| Guimaraes I et al., 2021 Portugal | Oral and Oropharynx | The EP-SHI is a culturally relevant, valid, and reliable PROM for assessing speech-related QoL in oral and oropharyngeal cancer patients [14]. | Modest sample size, lack of objective speech measures, and limited representation of oropharyngeal cancer patients. |

| Balaguer M et al., 2023 France | Oropharynx | The HoCoS fills a gap in head and neck oncology by providing a comprehensive measure of communication impairments. It allows for a better understanding of functional and psychosocial consequences in patient follow-up [15]. | Small sample size; requires further validation on a larger cohort. |

| Jimenez JE et al., 2021 United States | Lips and Oral Cavity | The extent of tongue resection was strongly associated with poor QoL outcomes after free tissue reconstruction of the oral cavity. This factor mediates the associations between other defect characteristics and QoL. The findings emphasize the importance of considering expected oral tongue defects when counseling patients and highlight the need for a multidisciplinary approach to postoperative care [26]. | The subjective nature of PROM, the retrospective cross-sectional design, and the variability in the time elapsed since treatment. Additionally, the sample consisted mostly of white patients, highlighting disparities in access to survivorship services. The study also lacked pre-treatment comparisons and had potential sampling bias, as patients attending survivorship clinics may differ from those who do not. |

| Larson AR et al., 2021 United States | Lips and Oral Cavity | STSG reconstruction is a reasonable option for early-stage floor of mouth carcinoma, though A-FOM may benefit from alternative reconstruction methods [28]. | Small sample size, low questionnaire response rate, lack of preoperative functional data, and absence of tumor depth information. |

| Monte LEFD et al., 2024 Brazil | Larynx | The electrolarynx is a viable and effective method for voice rehabilitation, positively impacting the QoL of laryngectomy patients [29]. | Small sample size, cross-sectional design, and limited generalizability due to the specific patient population. |

| Souza FGR et al., 2020 Brazil | Larynx | Tracheoesophageal prosthesis (TEP) is the gold standard for vocal rehabilitation, providing better QoL for TL patients [30]. | Recall bias due to long intervals since surgery, cross-sectional design limiting generalizability, and potential underrepresentation of the broader patient population. |

| Andreassen R et al., 2022 Norway | Head and Neck | Head and neck cancer treatment is associated with lasting impairment of oral HrQoL. A multidisciplinary approach and access to expert dental care are recommended to improve OHrQoL [31]. | Cross-sectional design limits causal inferences; potential recall bias due to self-reported data. |

| Yifru TA et al., 2021 Ethiopia | Head and Neck | Swallowing-related QoL is significantly impacted by dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients. Incorporating swallowing assessments into treatment protocols is recommended [9]. | Cross-sectional design limits causal inferences; potential recall bias due to self-reported data; findings may not be generalizable beyond the Ethiopian context. |

| Atula M 2024 Finland | Head and Neck | Psychosocial factors did not influence patient delay, but socioeconomic status and depression should be considered in clinical practice [18]. | A large number of patients were excluded or unable to participate, potential for recall bias, and the inability to assess psychological status prior to cancer diagnosis. |

| Hung CY 2024 Taiwan | Head and Neck | Pre-treatment HrQoL significantly impacts treatment-related complications, tolerance, and survival outcomes. QLQ-HN35 is a valuable predictor for treatment tolerance and outcomes in head and neck cancer patients [6]. | Single-center study, limiting generalizability. HrQoL was only assessed at baseline, without follow-up evaluations. Factors influencing HrQoL, such as socioeconomic status, were not fully explored. |

| Henry M et al., 2022 Canada | Head and Neck | HPV-negative patients generally experience greater psychological distress at diagnosis. HPV-positive patients require equal psychological support post-treatment. Head and neck clinics should address MDD, anxiety, depression, and quality of relationships [16]. | Single-center study, limiting generalizability. The majority of participants were male. Some missing data required imputation. |

| Scott SI et al., 2021 United States | Oropharynx | Functional and QoL outcomes were generally positive 1 year after treatment. Persistent impairment was observed in both groups, particularly in swallowing function [32]. | Small sample size. Limited generalizability due to a single-center study. |

| D’Andréa G et al., 2022 France | Oropharynx | Robotic-assisted salvage surgery demonstrated satisfactory quality of life, good functional sequelae, and favorable oncological outcomes compared to historical approaches [21]. | Single-center study, limiting generalizability. Small sample size. A high proportion of HPV-negative patients, which may affect outcomes. |

| Andersen LP et al., 2023 United States | Oropharynx | Patients with lower income, advanced cancer stage, and anxiety/depression had poorer QoL. Screening for these factors before treatment could improve patient support and outcomes [17]. | Conducted in a single U.S. region, limiting generalizability. The majority of participants were white and male. Some missing data required imputation. |

| Korsten LHA et al., 2021 Netherlands | Oropharynx | HPV-positive patients generally recover better in terms of QoL compared to HPV-negative patients. Findings highlight the importance of tailoring supportive care based on HPV status [7]. | Limited generalizability due to Dutch-specific treatment protocols. Potential selection bias due to exclusion criteria. Missing surveys due to patient death or loss to follow-up. |

| Goiato MC et al., 2020 Brazil | Oral and Oropharynx | QoL is significantly impacted by oral and oropharyngeal cancer treatment. Patients treated with surgery plus RT experience greater morbidity. Short-term follow-up is crucial for understanding recovery trends [8]. | Small sample size. Short follow-up period (only 3 months). Limited generalizability due to Brazil-specific treatment protocols. |

| Scott SI et al., 2023 Denmark | Oropharynx | TORS patients demonstrated better long-term swallowing function and QoL. RT patients showed functional recovery but persistent QoL decline. Further studies are needed to assess long-term recovery trends [32]. | Small sample size, particularly in the RT group. TORS and RT groups are not directly comparable due to different eligibility criteria. Limited generalizability due to Denmark-specific treatment protocols. |

| Deng J et al., 2022 United States | Oropharynx | The HN-LEF SI is a reliable and valid patient-reported outcome measure for assessing symptom burden and functional impairment due to lymphedema and fibrosis in head and neck cancer patients [33]. | Limited diversity in patient demographics, single-institution study, and potential sampling bias. |

| Harrowfield J et al., 2021 Australia | Oropharynx | Both HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPSCC patients experience nutritional decline during treatment, requiring equally intense nutritional intervention. HPV-positive patients may need additional support during recovery [34]. | Small sample size, lack of long-term follow-up, and limited geographic diversity. |

| Ramalingam K et al., 2024 India | Lips and Oral Cavity | The prediction model can help oral surgeons and oncologists improve planning and therapy for oral cancer patients [35]. | Modest sample size, reliance on patient-reported outcomes, and variability in time elapsed since treatment. |

| van Hinte G et al., 2021 Netherlands | Lips and Oral Cavity | SLNB is a preferred treatment strategy due to better short-term shoulder function and cost-effectiveness [25]. | Small sample size, lack of accessory nerve status data, and missing physiotherapy treatment details. |

| Balaji H et al., 2024 India | Lips and Oral Cavity | No agreement between patient-reported and clinician-rated outcomes; PROMs should be incorporated into routine clinical practice for comprehensive care [36]. | Modest sample size, lack of uniformity in cancer sub-sites, reliance on caregivers for illiterate participants, and absence of socioeconomic data. |

| Tuomi L et al., 2021 Sweden | Hypopharynx and Larynx | Patients with laryngeal cancer may require support in areas such as nutrition, swallowing, and voice rehabilitation up to 24 months post-RT [37]. | Small sample size, high dropout rate, and heterogeneity in tumor localization and stages. |

| Rogers SN et al., 2020 United Kingdom | Head and Neck | Baseline HRQOL is a valuable prognostic indicator for survival in head and neck cancer patients. Incorporating HRQOL into routine clinical care can enhance patient–clinician decision-making and recovery [38]. | Limited generalizability due to UK-based data, underrepresentation of older patients and those with poorer HRQOL, and incomplete data from some participants. |

| Zivkovic A et al., 2024 Serbia | Larynx | Extensive surgery and complications increase oxidative stress and inflammation, impacting QoL. Radical procedures correlate with higher symptom burden [39]. | Small sample size, single-center study, and lack of preoperative psychological assessments. |

| Grant SR et al., 2020 United States | Oropharynx | IMPT does not confer additional excess toxicity related to swallowing compared to photon-based RT [40]. | Single-institution study, decreasing patient numbers over long-term follow-up, and reliance on MDADI as the sole swallowing function measure. |

| Jia L et al., 2025 China. | Larynx | Dysphagia significantly impacts early QoL post-laryngectomy. FEES is effective for early swallowing function evaluation and rehabilitation guidance [41]. | Small sample size, limited follow-up duration, and exclusion of severely malnourished or non-compliant patients. |

| Nutting C et al., 2023 United Kingdom and Ireland | Oropharynx and Hypopharynx | DO-IMRT improved patient-reported swallowing function compared to standard IMRT. It should be considered a new standard of care for pharyngeal cancer RT [23]. | Single-center study limits generalizability. The majority of participants were male. Missing data required imputation. |

| Lam-Ubol A et al., 2023 Thailand | Oropharynx | Nutri-PEITC Jelly intake for 3 months is safe and improves QoL and PFS. Potential for PEITC to stabilize disease progression in advanced oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Further studies are needed to confirm long-term effects and mechanisms [20]. | Small sample size. Limited generalizability due to Thailand-specific treatment protocols. Potential selection bias due to exclusion criteria. |

| Aggarwal P et al., 2021 Netherlands | Oropharynx | The guided self-help exercise program improves swallowing and communication. Time since treatment influences effectiveness, with early intervention showing better results. Further research is needed to optimize rehabilitation strategies [42]. | Moderate adherence to the exercise program (59%). Limited generalizability due to Dutch-specific treatment protocols. Small sample size, particularly in subgroups. |

| Hajdú SF et al., 2022 Denmark | Head and Neck | The intervention showed benefits for secondary outcomes like QoL and mental health, but did not improve swallowing safety. Longer intervention durations and continued rehabilitation may be needed to mitigate functional deterioration in HNC survivors [43]. | The intervention period may have been too short; differences between groups were relatively small; high dropout rate (25% at 12 months). |

| Zhu X et al., 2022 China | Larynx | Combining acupuncture with swallowing exercises significantly enhances swallowing ability and QoLin post-surgical laryngeal cancer patients with dysphagia [44]. | Small sample size, single-center study, and lack of long-term follow-up data. |

| Karlsson T et al., 2022 Sweden | Larynx | Voice rehabilitation following RT for laryngeal cancer has long-term positive effects on communication and voice quality [45]. | Reduced number of participants over time, baseline differences between groups, and lack of significant acoustic findings. |

| Jansen F et al., 2020 Netherlands. | Larynx | The guided self-help exercise program effectively improves swallowing and communication in TL patients [46]. | Low adherence rate (59%) to the exercise program and lack of significant effects on shoulder problems, self-management, and HRQoL. |

| Johansson M et al., 2020 Sweden | Larynx | Voice rehabilitation following RT for laryngeal cancer is cost-saving from a societal perspective and provides better health outcomes [47]. | Small sample size, large variation in healthcare utilization and production loss, and potential recall bias in reporting sick leave days. |

| Li WX et al., 2023 China | Hypopharynx and Larynx | LPS and MAT provide satisfactory oncologic control and good functional outcomes for selected patients, especially those with early-stage disease [22]. | Retrospective design. Single-center study, limiting generalizability. High proportion of male patients. |

| Li WX et al., 2022 China | Hypopharynx and Larynx | Comprehensive treatment centered on surgery can achieve effective swallowing function while maintaining oncological control. Surgical defect size, local–regional recurrence, and distant metastasis independently affected survival. Pharyngo-cutaneous fistula and local–regional recurrence independently influenced swallowing function. Clinical stage, local–regional recurrence, decannulation, and feeding tube independently impacted quality of life [48]. | Single-center study, limiting generalizability. Retrospective design. |

| Liu T et al., 2024 China | Larynx | SCPL is effective in preserving laryngeal function while ensuring oncological safety, making it a viable surgical option for laryngeal cancer [12]. | Small sample size, single-center study, and potential bias due to the exclusion of patients with severe complications or incomplete follow-up. |

| Cocuzza S et al., 2020 Italy | Larynx | TEP is effective for voice rehabilitation, but complications like fistula-related disorders require careful management to optimize quality of life [13]. | Modest sample size, non-randomized design, and potential bias due to non-standardized protocols. |

| Theurer JA et al., 2025 Canada | Oropharynx | Instrumental swallowing assessments should be strongly considered alongside quality-of-life measures to best describe swallowing outcomes in studies of RT and/or surgery [49]. | Small sample size, limited follow-up duration, and lack of direct comparison with conventional surgical approaches. |

| Nakai MY et al., 2021 Brazil | Larynx | SPL is associated with better QoL than TL and should be considered for advanced laryngeal cancer treatment despite swallowing rehabilitation challenges [50]. | Small sample size, single-center study, and potential bias due to missing data and lack of preoperative QoL assessments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grigore, R.; Bejenaru, P.L.; Berteșteanu, G.S.; Nedelcu-Stancalie, R.I.; Schipor-Diaconu, T.E.; Rujan, S.A.; Taher, B.P.; Berteșteanu, Ș.V.G.; Popescu, B.; Popescu, I.D.; et al. Impact of Oncological Treatment on Quality of Life in Patients with Head and Neck Malignancies: A Systematic Literature Review (2020–2025). Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070379

Grigore R, Bejenaru PL, Berteșteanu GS, Nedelcu-Stancalie RI, Schipor-Diaconu TE, Rujan SA, Taher BP, Berteșteanu ȘVG, Popescu B, Popescu ID, et al. Impact of Oncological Treatment on Quality of Life in Patients with Head and Neck Malignancies: A Systematic Literature Review (2020–2025). Current Oncology. 2025; 32(7):379. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070379

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrigore, Raluca, Paula Luiza Bejenaru, Gloria Simona Berteșteanu, Ruxandra Ioana Nedelcu-Stancalie, Teodora Elena Schipor-Diaconu, Simona Andreea Rujan, Bianca Petra Taher, Șerban Vifor Gabriel Berteșteanu, Bogdan Popescu, Irina Doinița Popescu, and et al. 2025. "Impact of Oncological Treatment on Quality of Life in Patients with Head and Neck Malignancies: A Systematic Literature Review (2020–2025)" Current Oncology 32, no. 7: 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070379

APA StyleGrigore, R., Bejenaru, P. L., Berteșteanu, G. S., Nedelcu-Stancalie, R. I., Schipor-Diaconu, T. E., Rujan, S. A., Taher, B. P., Berteșteanu, Ș. V. G., Popescu, B., Popescu, I. D., Nicolaescu, A., Cîrstea, A. I., & Simion-Antonie, C. B. (2025). Impact of Oncological Treatment on Quality of Life in Patients with Head and Neck Malignancies: A Systematic Literature Review (2020–2025). Current Oncology, 32(7), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32070379