Developing the Understanding Palliative Care Module: A Quality Improvement Initiative Incorporating Public, Patient, and Family Caregiver Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review and Environmental Scan

2.2. Development of the Alberta Module

2.2.1. Process

2.2.2. Design

2.2.3. Video Content

2.3. Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Working Group Feedback

3.1.1. Use Plain Language

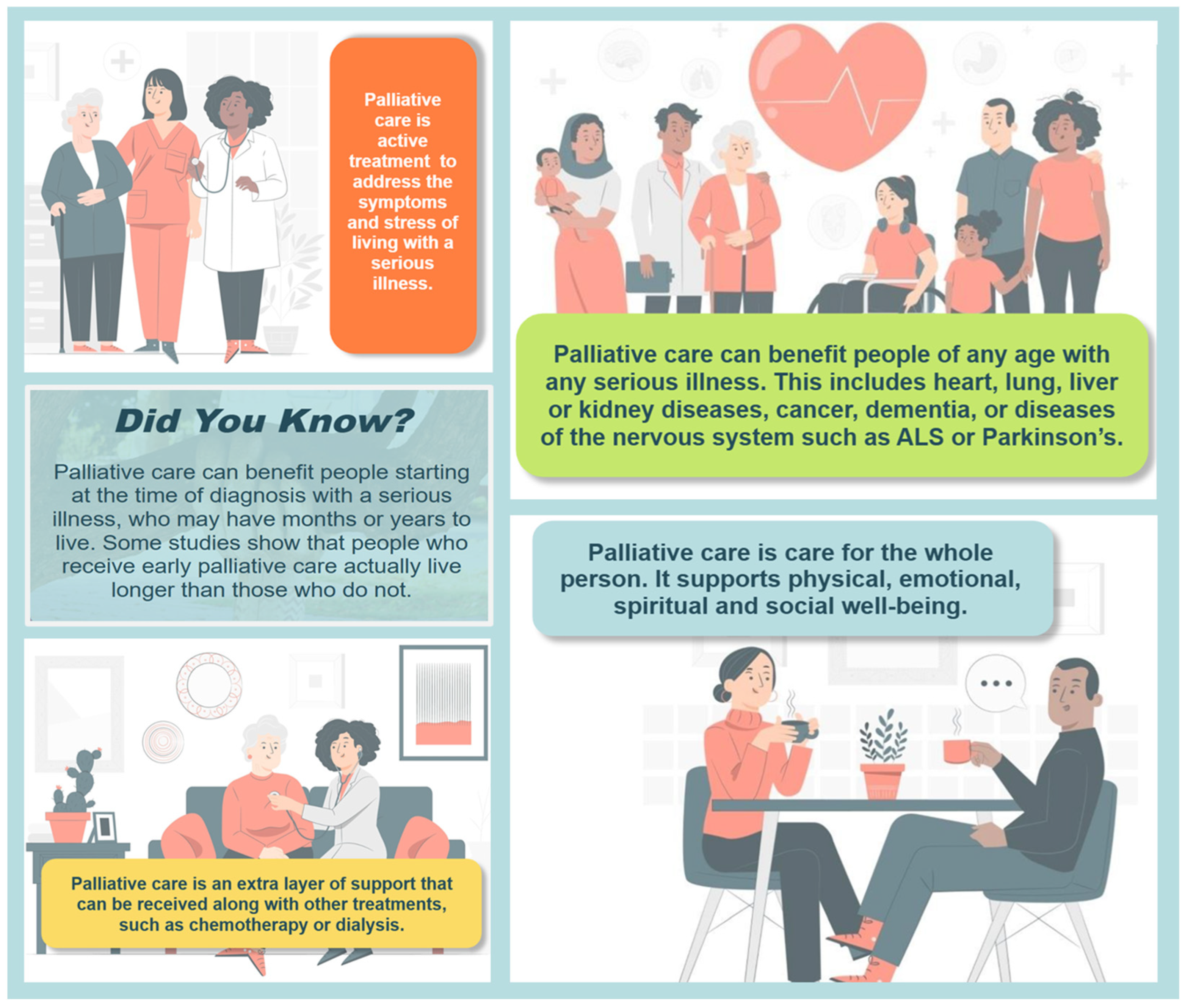

3.1.2. Focus on Positive Key Messages

3.1.3. Feature Albertans with Lived Experience of Palliative Care

3.1.4. Use Friendly, Engaging Graphics and Navigation

3.2. The Understanding Palliative Care Module

3.3. Dissemination of the Module

3.4. Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaasa, S.; Loge, J.H.; Aapro, M.; Albreht, T.; Anderson, R.; Bruera, E.; Brunelli, C.; Caraceni, A.; Cervantes, A.; Currow, D.C.; et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e588–e653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.; Hannon, B.L.; Zimmermann, C.; Bruera, E. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, B.; Song, Y.; Chang, L.; Tan, B. Effects of early palliative care on patients with incurable cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earp, M.; Cai, P.; Fong, A.; Blacklaws, K.; Pham, T.M.; Shack, L.; Sinnarajah, A. Hospital-based acute care in the last 30 days of life among patients with chronic disease that received early, late or no specialist palliative care: A retrospective cohort study of eight chronic disease groups. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Access to Palliative Care in Canada, 2023; CIHI: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/access-to-palliative-care-in-canada-2023-report-en.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Leighl, N.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; Hannon, B. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 2016, 188, E217–E227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.S.; Back, A.L.; Dettmar, N.S. Public Perceptions of Advance Care Planning, Palliative Care, and Hospice: A Scoping Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, S.; Earp, M.A.; Biondo, P.; Cheung, W.Y.; Kerba, M.; Tang, P.A.; Sinnarajah, A.; Watanabe, S.M.; Simon, J.E. Oncology Clinicians’ Challenges to Providing Palliative Cancer Care-A Theoretical Domains Framework, Pan-Cancer System Survey. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadul, N.; Elsayem, A.; Palmer, J.L.; Del Fabbro, E.; Swint, K.; Li, Z.; Poulter, V.; Bruera, E. Supportive versus palliative care: What’s in a name?: A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009, 115, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickey, J.; Flannery, M.; Cuthel, A.; Cho, J.; Grudzen, C.R.; The EMPallA Investigators. Barriers to recruitment into emergency department-initiated palliative care: A sub-study of a multi-site, randomized controlled trial. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, V.; Rahman, A.; Zhu, Y.; Enguidanos, S. Reluctance to Accept Palliative Care and Recommendations for Improvement: Findings From Semi-Structured Interviews With Patients and Caregivers. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2022, 39, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.; McLachlan, S.A.; Philip, J. Initial perceptions of palliative care: An exploratory qualitative study of patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, P.; Collins, A.; Boughey, M.; Philip, J. Reframing palliative care to improve the quality of life of people diagnosed with a serious illness. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 215, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roulston, E. Canadians’ Views on Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, S9–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National Palliative Care Strategy 2018; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/the-national-palliative-care-strategy-2018?language=en (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Health Canada. Framework on Palliative Care in Canada; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018; Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/palliative-care/framework-palliative-care-canada.html (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada. Blueprint for Action 2020–2025: A Progress Report. Canada. 2020. Available online: https://www.chpca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/QELCCC-Blueprint-for-Action-2020-2025-ENG-PRIN-H.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Abel, J.; Sallnow, L.; Murray, S.; Kerin, M. Each Community Is Prepared to Help: Community Development in End of Life Care Guidance on Ambition Six; The National Council for Palliative Care: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/J1448%20ncpc_strand_6_ART_NC.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Patterson, R.P.; Peacock, R.; Hazelwood, M. A Road Less Lonely: Moving Forward with Public Health Approaches to Death, Dying and Bereavement in Scotland; Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care: Edinburgh, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.palliativecarescotland.org.uk/content/publications/1526560117_A-Road-Less-Lonely-WEB.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Compassionate Alberta. Available online: https://covenanthealth.ca/about/centres-and-institutes/palliative-institute/compassionate-alberta (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- All Ireland Institute of Hospice and Palliative Care. Introduction to Palliative Care. Available online: https://thepalliativehub.com/introduction-to-palliative-care/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. MOTIVATE: Marketing and Messaging Palliative Care Toolkit. Available online: https://www.capc.org/toolkits/marketing-and-messaging-palliative-care/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Back, A. Serious Illness Messaging Toolkit. Available online: https://www.seriousillnessmessaging.org/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Back, A.L.; Grant, M.S.; McCabe, P.J. Public Messaging for Serious Illness Care in the Age of Coronavirus Disease: Cutting through Misconceptions, Mixed Feelings, and Distrust. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, C.; Mathews, J. Palliative Care Is the Umbrella, Not the Rain-A Metaphor to Guide Conversations in Advanced Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 681–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covenant Health Palliative Institute. Understanding Palliative Care. Available online: https://covenanthealth.ca/about/centres-and-institutes/palliative-institute/compassionate-alberta/learn-about-palliative-care (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Back, A.L.; Rotella, J.D.; Dashti, A.; DeBartolo, K.; Rosa, W.E.; October, T.W.; Grant, M.S. Top 10 Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Messaging for the Public. J. Palliat. Med. 2024, 27, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, G.; River, J.; Molloy, R.; Kemp, H.; Bellingham, B. Whose knowledge is of value? Co-designing healthcare education research with people with lived experience. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 120, 105616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flieger, S.P.; Chui, K.; Koch-Weser, S. Lack of Awareness and Common Misconceptions About Palliative Care Among Adults: Insights from a National Survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Interview Guide |

|---|

| How has palliative care helped/benefitted you/those close to you? What physical symptoms were/are challenging for you/your family member, and how has palliative care helped address those symptoms? Are you able to share some of the emotions you have experienced during your illness/your family member’s illness? Did palliative care help you cope emotionally with your/your family member’s illness? If so, in what way? At the time of your/your family member’s diagnosis, or in the time that followed, did you/they have spiritual questions or concerns? If yes, have you/they received support to help you/them on your/their journey? Did palliative care play a role? How did your/your family member’s illness impact you socially? Has palliative care provided support in this area? Has palliative care provided support to your family or caregivers? How has it helped them? What is something you have learned about palliative care since you/your family member received it? What do you think everyone should know about palliative care? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biondo, P.; Shantz, M.-A.; Zheng, Y.; Manning, M.; Kashuba, L. Developing the Understanding Palliative Care Module: A Quality Improvement Initiative Incorporating Public, Patient, and Family Caregiver Perspectives. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32040221

Biondo P, Shantz M-A, Zheng Y, Manning M, Kashuba L. Developing the Understanding Palliative Care Module: A Quality Improvement Initiative Incorporating Public, Patient, and Family Caregiver Perspectives. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(4):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32040221

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiondo, Patricia, Mary-Ann Shantz, Yuanjie (Bill) Zheng, Miranda Manning, and Louise Kashuba. 2025. "Developing the Understanding Palliative Care Module: A Quality Improvement Initiative Incorporating Public, Patient, and Family Caregiver Perspectives" Current Oncology 32, no. 4: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32040221

APA StyleBiondo, P., Shantz, M.-A., Zheng, Y., Manning, M., & Kashuba, L. (2025). Developing the Understanding Palliative Care Module: A Quality Improvement Initiative Incorporating Public, Patient, and Family Caregiver Perspectives. Current Oncology, 32(4), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32040221