Identification of Actionable Mutations in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Through Circulating Tumor DNA: Are We There Yet?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Actionable Genomic Mutations in mCRPC

3. Approved Targeted Therapies in mCRPC with Actionable Mutations

4. ctDNA Analysis for the Detection of Actionable Mutations in mCRPC

4.1. Analytical Validity

4.2. Clinical Validity

4.3. Clinical Utility

4.4. Limitations

5. Challenges and Limitations to ctDNA Analysis of Actionable Mutations in mCRPC

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADT | Androgen deprivation therapy |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| ARSI | Androgen receptor-signaling inhibitor |

| ATM | Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated |

| Bps | Base pairs |

| cfDNA | Cell-free DNA/circulating cell-free DNA |

| CHIP | Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| CRPC | Castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| CtIP | C-terminal-binding protein interacting protein |

| dHJs | Double Holliday junctions |

| dMMR | Deficiency in mismatch repair |

| DSBs | DNA double-strand breaks |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FFPE | Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue |

| HRR | Homologous recombination repair |

| mCRPC | Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| MMR | Mismatch repair |

| MMRd | Mismatch repair deficiency/deficient |

| MSI | Microsatellite instability |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PARP1 | Poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 |

| PARPI | PARP inhibitor |

| PAR | Poly-(ADP-ribose) |

| PC | Prostate cancer |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PSA | Prostate-specific antigen |

| PSMA | Prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| RPA | Replication protein A |

| rPFS | Radiographic progression-free survival |

| SCNC | Small-cell neuroendocrine prostate cancer |

| SDSA | Synthesis-dependent strand annealing |

| SSBs | Single-strand breaks |

| SsDNA | Single-stranded DNA |

| TMB | Tumor mutational burden |

References

- Aucamp, J.; Bronkhorst, A.J.; Badenhorst, C.P.S.; Pretorius, P.J. The diverse origins of circulating cell-free DNA in the human body: A critical re-evaluation of the literature. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2018, 93, 1649–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.C.M.; Massie, C.; Garcia-Corbacho, J.; Mouliere, F.; Brenton, J.D.; Caldas, C.; Pacey, S.; Baird, R.; Rosenfeld, N. Liquid biopsies come of age: Towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitzer, E.; Haque, I.S.; Roberts, C.E.S.; Speicher, M.R. Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettegowda, C.; Sausen, M.; Leary, R.J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Agrawal, N.; Bartlett, B.R.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Alani, R.M.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfil, R.D.; Al-Eyd, G. Evolving insights in blood-based liquid biopsies for prostate cancer interrogation. Oncoscience 2023, 10, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, T.H.; McEwen, R.; Dougherty, B.; Johnson, J.H.; Dry, J.R.; Lai, Z.; Ghazoui, Z.; Laing, N.M.; Hodgson, D.R.; Cruzalegui, F.; et al. Defining actionable mutations for oncology therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, H.I.; Halabi, S.; Tannock, I.; Morris, M.; Sternberg, C.N.; Carducci, M.A.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Higano, C.; Bubley, G.J.; Dreicer, R.; et al. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: Recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D.M.; Howard, L.E.; Sourbeer, K.N.; Amarasekara, H.S.; Chow, L.C.; Cockrell, D.C.; Hanyok, B.T.; Aronson, W.J.; Kane, C.J.; Terris, M.K.; et al. Predictors of Time to Metastasis in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Urology 2016, 96, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini, E.; Gray, K.P.; Shaw, G.K.; Evan, C.P.; Hamid, A.A.; Perry, C.E.; Kantoff, P.W.; Taplin, M.E.; Sweeney, C.J. Impact of new systemic therapies on overall survival of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in a hospital-based registry. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019, 22, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeeri, M.N.E.; Awies, M.; Constantinou, C. Prostate Cancer, Pathophysiology and Recent Developments in Management: A Narrative Review. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

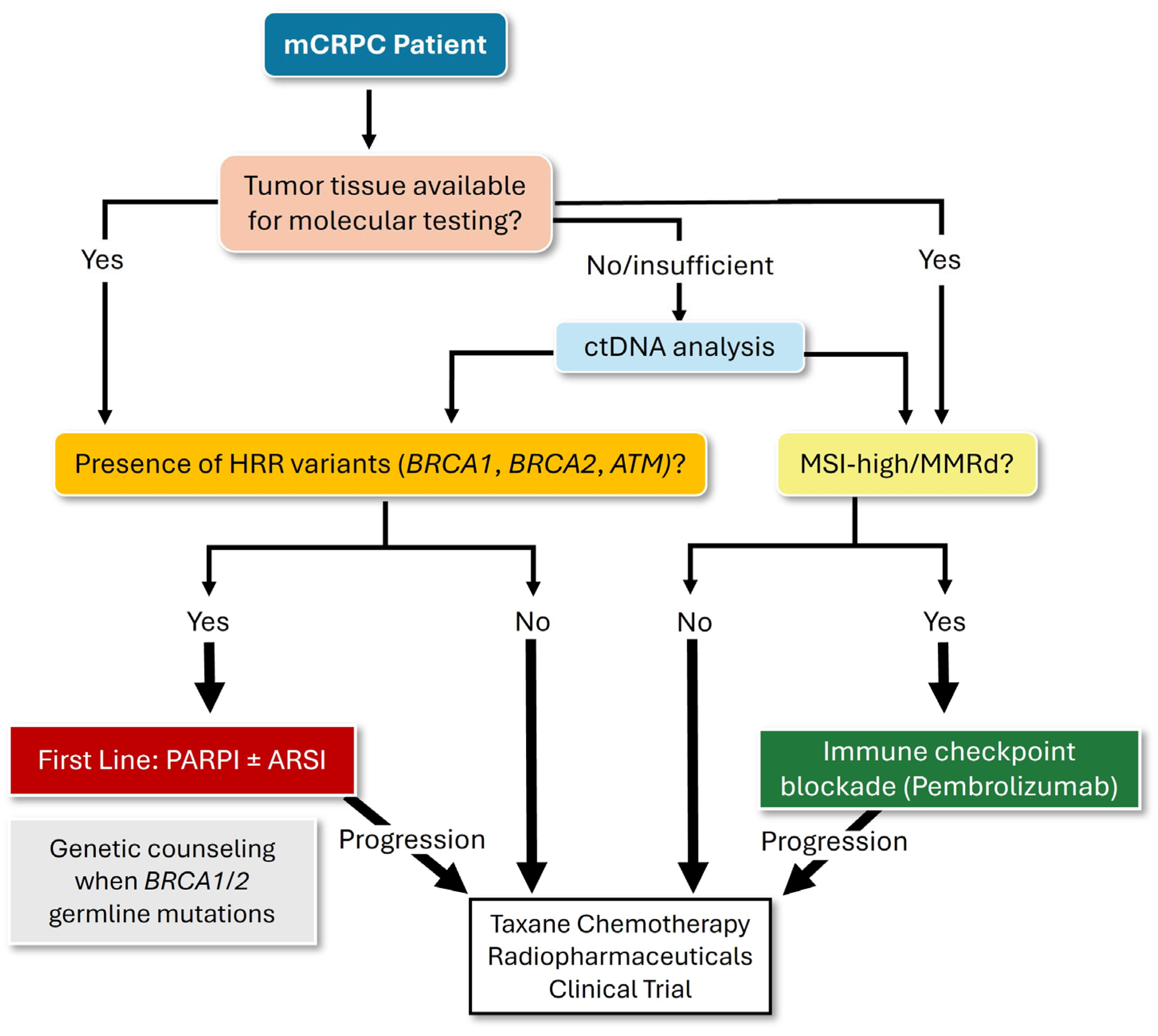

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Barocas, D.; Bitting, R.; Bryce, A.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’Amico, A.V.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 1067–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.Y.; Rumble, R.B.; Agarwal, N.; Cheng, H.H.; Eggener, S.E.; Bitting, R.L.; Beltran, H.; Giri, V.N.; Spratt, D.; Mahal, B.; et al. Germline and Somatic Genomic Testing for Metastatic Prostate Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merseburger, A.S.; Waldron, N.; Ribal, M.J.; Heidenreich, A.; Perner, S.; Fizazi, K.; Sternberg, C.N.; Mateo, J.; Wirth, M.P.; Castro, E.; et al. Genomic Testing in Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: A Pragmatic Guide for Clinicians. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.W.S.; Wyatt, A.W. Building confidence in circulating tumour DNA assays for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, A.W.; Annala, M.; Aggarwal, R.; Beja, K.; Feng, F.; Youngren, J.; Foye, A.; Lloyd, P.; Nykter, M.; Beer, T.M.; et al. Concordance of Circulating Tumor DNA and Matched Metastatic Tissue Biopsy in Prostate Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djx118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukachinsky, H.; Madison, R.W.; Chung, J.H.; Gjoerup, O.V.; Severson, E.A.; Dennis, L.; Fendler, B.J.; Morley, S.; Zhong, L.; Graf, R.P.; et al. Genomic Analysis of Circulating Tumor DNA in 3334 Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer Identifies Targetable BRCA Alterations and AR Resistance Mechanisms. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 3094–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayrhofer, M.; De Laere, B.; Whitington, T.; Van Oyen, P.; Ghysel, C.; Ampe, J.; Ost, P.; Demey, W.; Hoekx, L.; Schrijvers, D.; et al. Cell-free DNA profiling of metastatic prostate cancer reveals microsatellite instability, structural rearrangements and clonal hematopoiesis. Genome Med. 2018, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.; Van Allen, E.M.; Wu, Y.M.; Schultz, N.; Lonigro, R.J.; Mosquera, J.M.; Montgomery, B.; Taplin, M.E.; Pritchard, C.C.; Attard, G.; et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell 2015, 161, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Johnson, A.; Holla, V.; Bailey, A.M.; Brusco, L.; Chen, K.; Routbort, M.; Patel, K.P.; Zeng, J.; Kopetz, S.; et al. A decision support framework for genomically informed investigational cancer therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Lu, C.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Nakazawa, M.; Roeser, J.C.; Chen, Y.; Mohammad, T.A.; Fedor, H.L.; Lotan, T.L.; et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloberti, T.; De Leo, A.; Coluccelli, S.; Sanza, V.; Gruppioni, E.; Altimari, A.; Zagnoni, S.; Giunchi, F.; Vasuri, F.; Fiorentino, M.; et al. Multi-Gene Next-Generation Sequencing Panel for Analysis of BRCA1/BRCA2 and Homologous Recombination Repair Genes Alterations Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

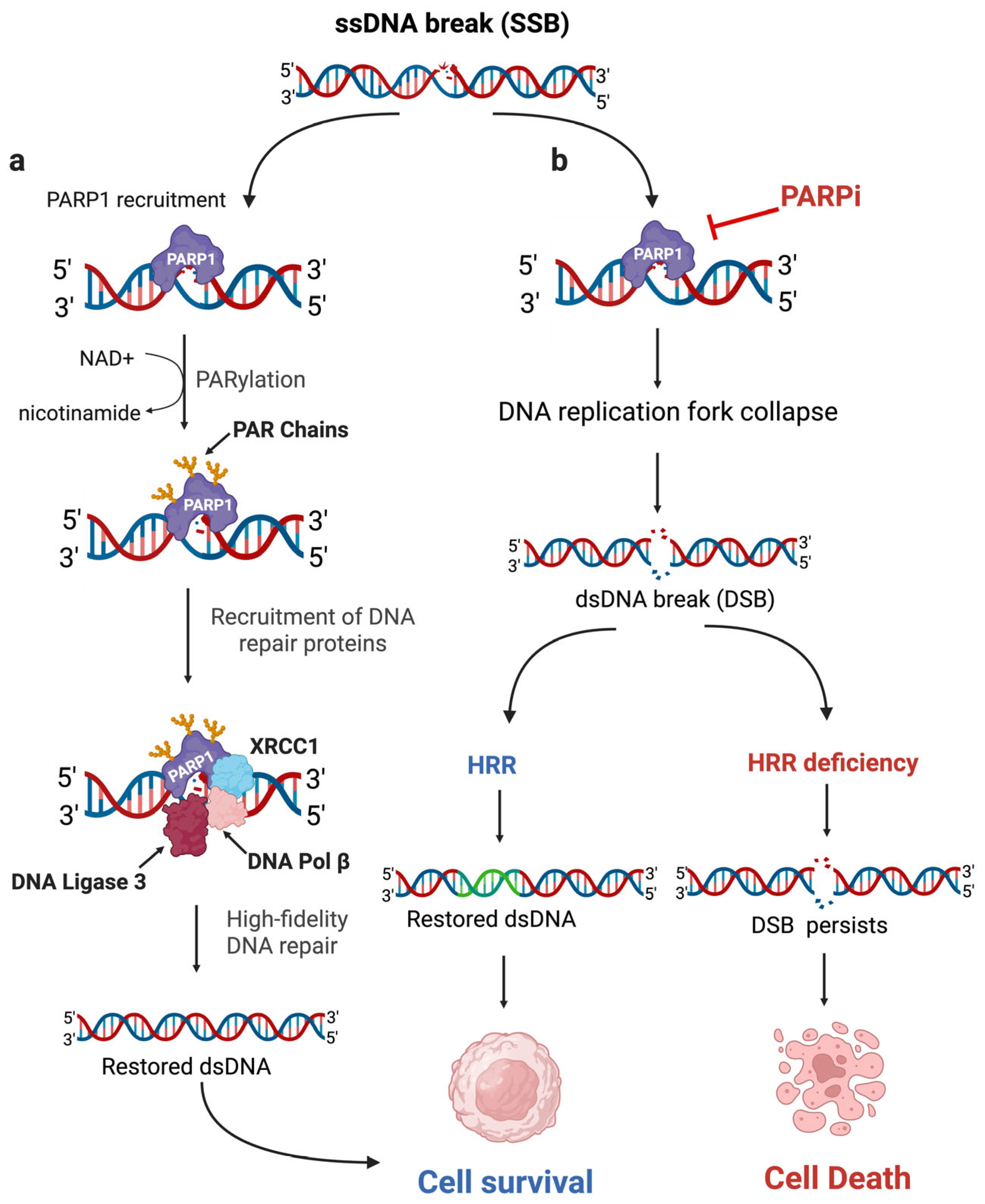

- Caldecott, K.W. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray Chaudhuri, A.; Nussenzweig, A. The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konecny, G.E.; Kristeleit, R.S. PARP inhibitors for BRCA1/2-mutated and sporadic ovarian cancer: Current practice and future directions. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 1157–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, D.K.; Mishra, D.; Singh, R.P. Targeting DNA repair for cancer treatment: Lessons from PARP inhibitor trials. Oncol. Res. 2023, 31, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

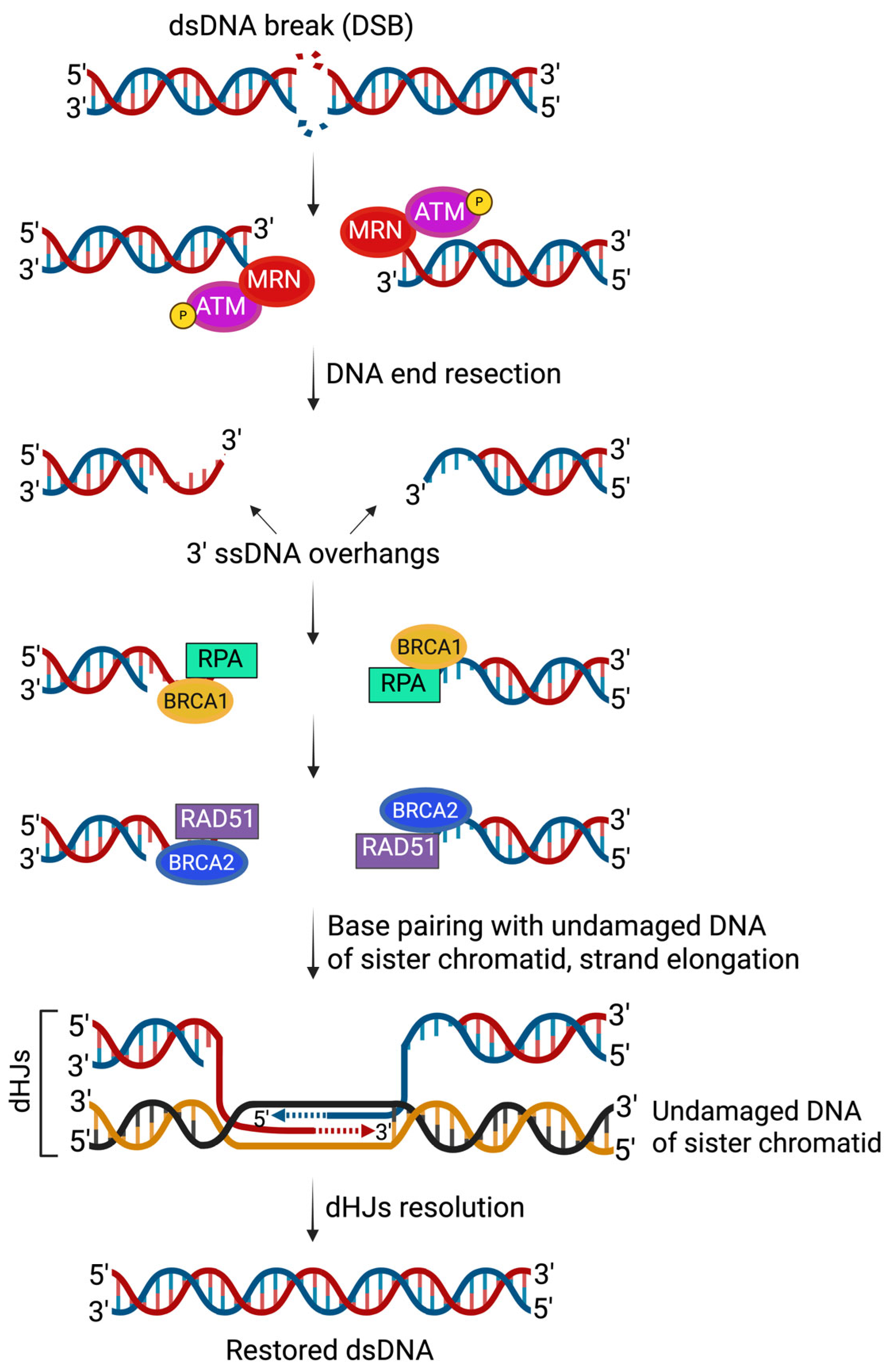

- Symington, L.S.; Gautier, J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011, 45, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.D.; Shah, S.S.; Heyer, W.D. Homologous recombination and the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 10524–10535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Kim, W.; Kloeber, J.A.; Lou, Z. DNA end resection and its role in DNA replication and DSB repair choice in mammalian cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carusillo, A.; Mussolino, C. DNA Damage: From Threat to Treatment. Cells 2020, 9, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.J.; Mehta, A.; Macedo, G.S.; Borisov, P.S.; Kanesvaran, R.; El Metnawy, W. Genetic testing for homologous recombination repair (HRR) in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Challenges and solutions. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 1600–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, C.; Di Carlo, E. Molecular Targeted Therapies in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. Cancers 2023, 15, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valsecchi, A.A.; Dionisio, R.; Panepinto, O.; Paparo, J.; Palicelli, A.; Vignani, F.; Di Maio, M. Frequency of Germline and Somatic. Cancers 2023, 15, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, H.; McCabe, N.; Lord, C.J.; Tutt, A.N.; Johnson, D.A.; Richardson, T.B.; Santarosa, M.; Dillon, K.J.; Hickson, I.; Knights, C.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, W.G., Jr. The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, H.E.; Schultz, N.; Thomas, H.D.; Parker, K.M.; Flower, D.; Lopez, E.; Kyle, S.; Meuth, M.; Curtin, N.J.; Helleday, T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005, 434, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abida, W.; Cheng, M.L.; Armenia, J.; Middha, S.; Autio, K.A.; Vargas, H.A.; Rathkopf, D.; Morris, M.J.; Danila, D.C.; Slovin, S.F.; et al. Analysis of the Prevalence of Microsatellite Instability in Prostate Cancer and Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Aulakh, L.K.; Lu, S.; Kemberling, H.; Wilt, C.; Luber, B.S.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017, 357, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Prostate Cancer Version 2. 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Aggarwal, R.; Huang, J.; Alumkal, J.J.; Zhang, L.; Feng, F.Y.; Thomas, G.V.; Weinstein, A.S.; Friedl, V.; Zhang, C.; Witte, O.N.; et al. Clinical and Genomic Characterization of Treatment-Emergent Small-Cell Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer: A Multi-institutional Prospective Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2492–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Survival with Olaparib in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopsack, K.H. Efficacy of PARP Inhibition in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer is Very Different with Non-BRCA DNA Repair Alterations: Reconstructing Prespecified Endpoints for Cohort B from the Phase 3 PROfound Trial of Olaparib. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Piulats, J.M.; Reaume, M.N.; Ostler, P.; McDermott, R.; Gingerich, J.R.; Pintus, E.; Sridhar, S.S.; Bambury, R.M.; Emmenegger, U.; et al. Rucaparib or Physician’s Choice in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karzai, F.; Madan, R.A.; Figg, W.D. How far does a new horizon extend for rucaparib in metastatic prostate cancer? Transl. Cancer Res. 2024, 13, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abida, W.; Patnaik, A.; Campbell, D.; Shapiro, J.; Bryce, A.H.; McDermott, R.; Sautois, B.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Bambury, R.M.; Voog, E.; et al. Rucaparib in Men with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Harboring a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Gene Alteration. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3763–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, N.W.; Armstrong, A.J.; Thiery-Vuillemin, A.; Oya, M.; Shore, N.; Loredo, E.; Procopio, G.; de Menezes, J.; Girotto, G.; Arslan, C.; et al. Abiraterone and Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, F.; Clarke, N.W.; Oya, M.; Shore, N.; Procopio, G.; Guedes, J.D.; Arslan, C.; Mehra, N.; Parnis, F.; Brown, E.; et al. Olaparib plus abiraterone versus placebo plus abiraterone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (PROpel): Final prespecified overall survival results of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, J.; Xu, J.; Weinstock, C.; Brave, M.H.; Bloomquist, E.; Fiero, M.H.; Schaefer, T.; Pathak, A.; Abukhdeir, A.; Bhatnagar, V.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Olaparib in Combination with Abiraterone for Treatment of Patients with BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.N.; Rathkopf, D.; Smith, M.R.; Efstathiou, E.; Attard, G.; Olmos, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Small, E.J.; Pereira de Santana Gomes, A.J.; Roubaud, G.; et al. Niraparib and Abiraterone Acetate for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3339–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, K.N.; Castro, E.; Attard, G.; Smith, M.R.; Sandhu, S.; Efstathiou, E.; Roubaud, G.; Small, E.J.; de Santana Gomes, A.P.; Rathkopf, D.E.; et al. Niraparib and Abiraterone Acetate plus Prednisone in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: Final Overall Survival Analysis for the Phase 3 MAGNITUDE Trial. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Azad, A.A.; Carles, J.; Fay, A.P.; Matsubara, N.; Heinrich, D.; Szczylik, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Young Joung, J.; Fong, P.C.C.; et al. Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with first-line metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TALAPRO-2): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Azad, A.A.; Carles, J.; Fay, A.P.; Matsubara, N.; Szczylik, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Young Joung, J.; Fong, P.C.C.; Voog, E.; et al. Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Final overall survival results from the randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 TALAPRO-2 trial. Lancet 2025, 406, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, L.; Lemery, S.J.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Microsatellite Instability-High Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3753–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marabelle, A.; O’Malley, D.M.; Hendifar, A.E.; Ascierto, P.A.; Motola-Kuba, D.; Penel, N.; Cassier, P.A.; Bariani, G.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Doi, T.; et al. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite-instability-high and mismatch-repair-deficient advanced solid tumors: Updated results of the KEYNOTE-158 trial. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Piulats, J.M.; Gross-Goupil, M.; Goh, J.; Ojamaa, K.; Hoimes, C.J.; Vaishampayan, U.; Berger, R.; Sezer, A.; Alanko, T.; et al. Pembrolizumab for Treatment-Refractory Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Multicohort, Open-Label Phase II KEYNOTE-199 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescigno, P.; Fenor de la Maza, M.D.; Tovey, H.; Villacampa, G.; Cafferty, F.; Burnett, S.; Stiles, M.; Gurel, B.; Tunariu, N.; Carreira, S.; et al. PERSEUS1: An Open-label, Investigator-initiated, Single arm, Phase 2 Trial Testing the Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer with Mismatch Repair Deficiency and Other Immune-sensitive Molecular Subtypes. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.N.; Barnicle, A.; Sibilla, C.; Lai, Z.; Corcoran, C.; Barrett, J.C.; Adelman, C.A.; Qiu, P.; Easter, A.; Dearden, S.; et al. Detection of BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM Alterations in Matched Tumor Tissue and Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients with Prostate Cancer Screened in PROfound. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbury, C.A.; Creeden, J.; Yip, W.K.; Smith, D.L.; Pattani, V.; Maxwell, K.; Sawchyn, B.; Gjoerup, O.; Meng, W.; Skoletsky, J.; et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne(R)CDx, a comprehensive genomic profiling assay for solid tumors. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiota, M.; Matsubara, N.; Kato, T.; Eto, M.; Osawa, T.; Abe, T.; Shinohara, N.; Nishimoto, K.; Yasumizu, Y.; Tanaka, N.; et al. Genomic profiling and clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA in metastatic prostate cancer: SCRUM-Japan MONSTAR SCREEN project. BJC Rep. 2024, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, N.; de Bono, J.; Olmos, D.; Procopio, G.; Kawakami, S.; Ürün, Y.; van Alphen, R.; Flechon, A.; Carducci, M.A.; Choi, Y.D.; et al. Olaparib Efficacy in Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer and BRCA1, BRCA2, or ATM Alterations Identified by Testing Circulating Tumor DNA. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstathiou, E.; Titus, M.; Wen, S.; Hoang, A.; Karlou, M.; Ashe, R.; Tu, S.M.; Aparicio, A.; Troncoso, P.; Mohler, J.; et al. Molecular characterization of enzalutamide-treated bone metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, J.; Mateo, J.; Yuan, W.; Mossop, H.; Porta, N.; Miranda, S.; Perez-Lopez, R.; Dolling, D.; Robinson, D.R.; Sandhu, S.; et al. Circulating Cell-Free DNA to Guide Prostate Cancer Treatment with PARP Inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J.; Lefterova, M.I.; Artyomenko, A.; Kasi, P.M.; Nakamura, Y.; Mody, K.; Catenacci, D.V.T.; Fakih, M.; Barbacioru, C.; Zhao, J.; et al. Validation of Microsatellite Instability Detection Using a Comprehensive Plasma-Based Genotyping Panel. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 7035–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, A.; Rauterkus, G.P.; Vaishampayan, U.N.; Barata, P.C. Overcoming Obstacles in Liquid Biopsy Developments for Prostate Cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barata, P.; Agarwal, N.; Nussenzveig, R.; Gerendash, B.; Jaeger, E.; Hatton, W.; Ledet, E.; Lewis, B.; Layton, J.; Babiker, H.; et al. Clinical activity of pembrolizumab in metastatic prostate cancer with microsatellite instability high (MSI-H) detected by circulating tumor DNA. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FoundationOne Liquid CDx—P190032. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf19/P190032S011A.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Stout, L.A.; Hunter, C.; Schroeder, C.; Kassem, N.; Schneider, B.P. Clinically significant germline pathogenic variants are missed by tumor genomic sequencing. NPJ Genom. Med. 2023, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piombino, C.; Pipitone, S.; Tonni, E.; Mastrodomenico, L.; Oltrecolli, M.; Tchawa, C.; Matranga, R.; Roccabruna, S.; D’Agostino, E.; Pirola, M.; et al. Homologous Recombination Repair Deficiency in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: New Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirahata, T.; Ul Quraish, R.; Quraish, A.U.; Ul Quraish, S.; Naz, M.; Razzaq, M.A. Liquid Biopsy: A Distinctive Approach to the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Cancer. Cancer Inform. 2022, 21, 11769351221076062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.; Won, D.; Shin, S.; Cho, K.S.; Park, J.W.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.D.; Kang, S.; Lee, S.T.; Choi, J.R.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis on Metastatic Prostate Cancer with Disease Progression. Cancers 2023, 15, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Caldito, N. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the central nervous system: A focus on autoimmune disorders. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1213448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, N.M.; Maurice-Dror, C.; Herberts, C.; Tu, W.; Fan, W.; Murtha, A.J.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Kwan, E.M.; Parekh, K.; Schonlau, E.; et al. Prediction of plasma ctDNA fraction and prognostic implications of liquid biopsy in advanced prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, E.M.; Wyatt, A.W.; Chi, K.N. Towards clinical implementation of circulating tumor DNA in metastatic prostate cancer: Opportunities for integration and pitfalls to interpretation. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1054497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfo, C.D.; Madison, R.W.; Pasquina, L.W.; Brown, D.W.; Huang, Y.; Hughes, J.D.; Graf, R.P.; Oxnard, G.R.; Husain, H. Measurement of ctDNA Tumor Fraction Identifies Informative Negative Liquid Biopsy Results and Informs Value of Tissue Confirmation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 2452–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annala, M.; Vandekerkhove, G.; Khalaf, D.; Taavitsainen, S.; Beja, K.; Warner, E.W.; Sunderland, K.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Eigl, B.J.; Finch, D.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Genomics Correlate with Resistance to Abiraterone and Enzalutamide in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberts, C.; Wyatt, A.W. Technical and biological constraints on ctDNA-based genotyping. Trends Cancer 2021, 7, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, K.; Konnick, E.Q.; Schweizer, M.T.; Sokolova, A.O.; Grivas, P.; Cheng, H.H.; Klemfuss, N.M.; Beightol, M.; Yu, E.Y.; Nelson, P.S.; et al. Association of Clonal Hematopoiesis in DNA Repair Genes With Prostate Cancer Plasma Cell-free DNA Testing Interference. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial (NCT#) | Regimen | Population | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROpel (NCT03732820) | Olaparib + Abiraterone (vs. placebo + Abiraterone) | No prior systemic treatment. Irrespective of HRR status. | Overall rPFS benefit observed. No statistically significant OS benefit reached for the overall population, though the longest OS reported among first-line mCRPC trials to date. HRR Mutations: Strongest rPFS benefit observed, particularly with BRCA mutations. No HRR Mutations: Statistically significant rPFS benefit observed, though smaller than in HRR-positive group. |

| MAGNITUDE (NCT03748641) | Niraparib + Abiraterone (vs. placebo + Abiraterone) | No prior systemic treatment (except in earliest hormone-sensitive setting). HRR-mutated vs. HRR-wildtype | HRR Mutations: Significant rPFS improvement and longer OS, particularly with BRCA mutations. No HRR Mutations: No rPFS or OS benefit observed. The combination was stopped in this cohort due to statistical futility. |

| TALAPRO-2 (NCT03395197) | Talazoparib + Enzalutamide (vs. placebo + Enzalutamide) | No prior systemic treatment (except in earliest hormone-sensitive setting). HRR mutation not required but analyzed as subgroups. | Overall improvement in rPFS observed, with OS improvements observed regardless of HRR status. HRR Mutations: Strongest rPFS and OS improvements observed, particularly with BRCA1/2 mutations. No HRR Mutations: Statistically significant rPFS improvement observed. OS benefit, though smaller than in HRR-positive group. |

| Feature | Somatic Variant | Germline Variant |

|---|---|---|

| Origin/Location | Acquired; confined only to tumor cells. | Inherited; found in every cell of the body. |

| Treatment Consequence | Guides individual therapy (e.g., PARPI eligibility). | Guides individual therapy (e.g., PARPI eligibility) and may affect overall prognosis or choice of subsequent lines of treatment. |

| Familial Consequence | None: Cannot be passed to children or relatives. | Major. 50% risk of transmission to offspring, requiring genetic counseling and cascade testing for blood relatives. |

| Patient Risk Consequence | None regarding risk of other primary cancers. | High lifetime risk for other primary cancers (e.g., pancreatic), requiring enhanced screening. |

| Assay | Sample Type | Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| FoundationOne®CDx | FFPE tissue | Alterations in 324 genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, BARD1, BRIP1, CDK12, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCL, PALB2, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, and RAD54L genes, as well as MSI-H, MMRd, and TMB-H. |

| FoundationOne® Liquid CDx | Plasma cfDNA | Alterations in 311 genes—a more constrained version of FoundationOne®CDx. |

| Guardant360® CDx | Plasma cfDNA | Alterations in >70 genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, and MSI-high |

| BRACAnalysis CDx® | Peripheral (whole) blood | Germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tao, W.; Sabel, A.; Bonfil, R.D. Identification of Actionable Mutations in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Through Circulating Tumor DNA: Are We There Yet? Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120692

Tao W, Sabel A, Bonfil RD. Identification of Actionable Mutations in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Through Circulating Tumor DNA: Are We There Yet? Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):692. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120692

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Wensi, Amanda Sabel, and R. Daniel Bonfil. 2025. "Identification of Actionable Mutations in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Through Circulating Tumor DNA: Are We There Yet?" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120692

APA StyleTao, W., Sabel, A., & Bonfil, R. D. (2025). Identification of Actionable Mutations in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Through Circulating Tumor DNA: Are We There Yet? Current Oncology, 32(12), 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120692