Breast Cancer Therapy by Small-Molecule Reactivation of Mutant p53

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

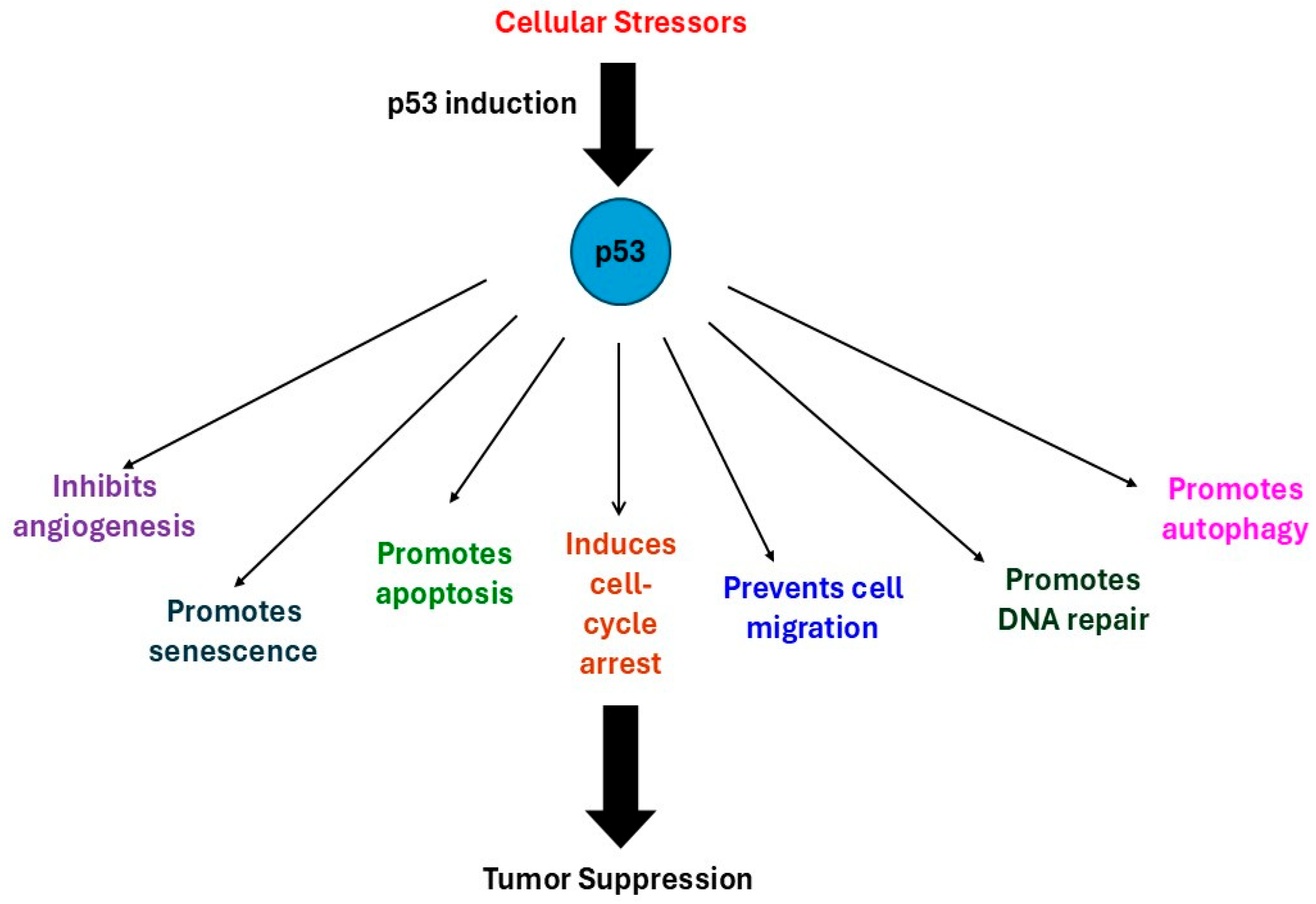

2. Tumor Suppressor p53

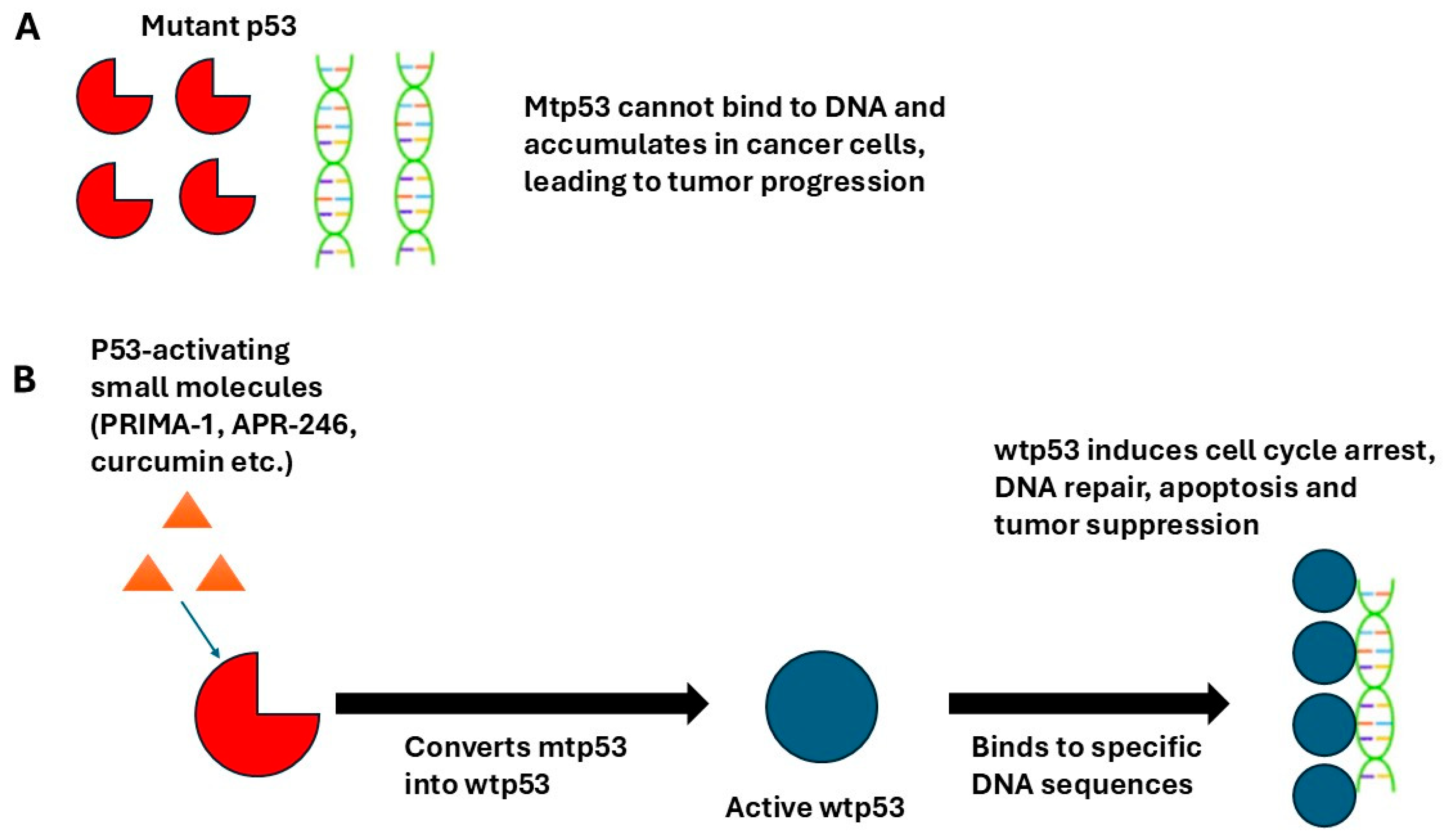

3. Restoration of wtp53 Activity by PRIMA-1

4. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

5. APR-246 Studies

6. Other Small Molecule Activators of mtp53

7. Restoration of wtp53 Activity by Natural Compounds

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Newman, L.A.; Freedman, R.A.; Smith, R.A.; Star, J.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeagu, E.I.; Obeagu, G.U. Breast cancer: A review of risk factors and diagnosis. Medicine 2024, 103, e36905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012, 490, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, H.A.; El-Hadaad, H.A. Current approaches in treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2015, 12, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.P. Cancer. P53, guardian of the genome. Nature 1992, 358, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, A.J. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 1997, 88, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klymkowsky, M.W.; Savagner, P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.I.; Tuszynski, J. The molecular mechanism of action of methylene quinuclidinone and its effects on the structure of p53 mutants. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 37137–37156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. The cell-cycle arrest and apoptotic functions of p53 in tumor initiation and progression. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a026104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.J.; Synnot, N.C.; O’Grady, S.; Crown, J. Targeting p53 for the treatment of cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 79, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilfou, J.T.; Lowe, S.W. Tumor suppressive functions of p53. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a001883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Besch-Williford, C.; Benakanakere, I.; Hyder, S.M. Re-activation of the p53 pathway inhibits in vivo and in vitro growth of hormone-dependent human breast cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2007, 31, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykov, V.J.; Issaeva, N.; Shilov, A.; Hultcrantz, M.; Pugacheva, E.; Chumakov, P.; Bergman, J.; Wiman, K.G.; Selivanova, G. Restoration of the tumor suppressor function to mutant p53 by a low-molecular-weight compound. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Jianbo Wu Stancel, G.M.; Hyder, S.M. P53-dependent inhibition of progestin-induced VEGF expression in human breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 93, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Besch-Williford, C.; Hyder, S.M. PRIMA-1 inhibits growth of breast cancer cells by re-activating mutant p53 protein. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 35, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Besch-Williford, C.; Benakanakere, I.; Thorpe, P.E.; Hyder, S.M. Targeting mutant p53 protein and the tumor vasculature: An effective combination therapy for advanced breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 125, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinter, S.Z.; Liang, Y.; Huang, S.-Y.; Hyder, S.M.; Zou, X. An inverse docking approach for identifying new potential anti-cancer targets. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2011, 29, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aysola, K.; Desai, A.; Welch, C.; Xu, J.; Qin, Y.; Reddy, V.; Matthews, R.; Owens, C.; Okoli, J.; Beech, D.J.; et al. Triple negative breast cancer—An overview. Hered. Genet. 2013, 2013 (Suppl. 2), 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Choi, J.H.; Nam, J.S. Targeting cancer stem cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, T.P.; Slight, S.H.; Hyder, S.M. Role of reactivating mutant p53 protein in suppressing growth and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, P.; Monti, P.; Speciale, A.; Cutrona, G.; Matis, S.; Fais, F.; Taiana, E.; Neri, A.; Bomben, R.; Gentile, M.; et al. Antitumor effects of PRIMA-1 and PRIMA-1Met (APR246) in hematological malignancies: Still a mutant p53-dependent affair? Cells 2021, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdrix, A.; Najem, A.; Saussez, S.; Awada, A.; Journe, F.; Ghanem, G.; Krayem, M. PRIMA-1 and PRIMA-1Met (APR-246): From mutant/wild type p53 reactivation to unexpected mechanisms underlying their potent anti-tumor effect in combinatorial therapies. Cancers 2017, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.J.; Synnott, N.C.; Crown, J. Mutant p53 in breast cancer: Potential as a therapeutic target and biomarker. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 170, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Mafuvadze, B.; Besch-Williford, C.; Hyder, S.M. A combination of p53-activating APR-246 and phosphatidylserine-targeting antibody potently inhibits tumor development in hormone-dependent mutant p53-expressing breast cancer xenografts. Breast Cancer 2018, 10, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Besch-Williford, C.; Mafuvadze, B.; Brekken, R.A.; Hyder, S. Combined treatment with p53-activating drug APR-246 and a phosphatidylserine-targeting antibody, 2aG4, inhibits growth of human triple-negative breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Rep. Rev. 2020, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S.; Bykov, V.J.; Ali, D.; Andrén, O.; Cherif, H.; Tidefelt, U.; Uggla, B.; Yachnin, J.; Juliusson, G.; Moshfegh, A.; et al. Targeting p53 in vivo: A first-in-human study with p53-targeting compound APR-246 in refractory hematologic malignancies and prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3633–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Besch-Williford, C.; Cook, M.T.; Belenchia, A.; Brekken, R.A.; Hyder, S.M. APR-246 alone and in combination with a phosphatidylserine-targeting antibody inhibits lung metastasis of human triple-negative breast cancer cells in nude mice. Breast Cancer 2019, 11, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykov, V.J.N.; Issaeva, N.; Zache, N.; Shilov, A.; Hultcrantz, M.; Bergman, J.; Selivanova, G.; Wiman, K.G. Reactivation of mutant p53 and induction of apoptosis in human tumor cells by maleimide analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 30384–30391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zache, N.; Lambert, J.M.R.; Rokaeus, N.; Shen, J.; Hainaut, P.; Bergman, J.; Wiman, K.G.; Bykov, V.J.N. Mutant p53 targeting by the low molecular weight compound STIMA-1. Mol. Oncol. 2008, 2, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, K.Y.; Maleki Vareki, S.; Danter, W.R.; Koropatnick, J. COTI-2, a novel small molecule that is active against multiple human cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41363–41379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synnott, N.C.; O’Connell, D.; Crown, J.; Duffy, M.J. COTI-2 reactivates mutant p53 and inhibits growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 179, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.A.; Von Euler, M.; Abrahmsen, L.B. Restoration of conformation of mutant p53. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaeva, N.; Bozko, P.; Enge, M.; Protopopova, M.; Verhoef, L.G.G.C.; Masucci, M.; Pramanik, A.; Selivanova, G. Small molecule RITA binds to p53, blocks p53–HDM-2 interaction and activates p53 function in tumors. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weilbacher, A.; Gutekunst, M.; Oren, M.; Aulitzky, W.E.; van der Kuip, H. RITA can induce cell death in p53-defective cells independently of p53 function via activation of JNK/SAPK and p38. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyser, B.D.; Hermone, A.; Salamoun, J.M.; Burnett, J.C.; Hollingshead, M.G.; McGrath, C.F.; Gussio, R.; Wipf, P. Specific RITA modification produces hyperselective cytotoxicity while maintaining in vivo antitumor efficacy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzio-Kuter, A.M.; Xu, L.; McBrayer, M.K.; Dominique, R.; Li, H.H.; Fahr, B.J.; Brown, A.M.; Wiebesiek, A.E.; Russo, B.M.; Mulligan, C.L.; et al. Restoration of the tumor suppressor function of Y220C-mutant p53 by rezatapopt, a small-molecule reactivator. Cancer Discov. 2025, 15, 1159–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papavassiliou, K.A.; Vassiliou, A.G.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Rezatapopt: A promising small-molecule “refolder” specific for TP53Y220C mutant tumors. Neoplasia 2025, 67, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schram, A.M.; Shapiro, G.I.; Johnson, M.L.; Tolcher, A.W.; Thompson, J.A.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Vandross, A.L.; Kummar, S.; Parikh, A.R.; Shepard, D.R.; et al. Updated phase I results from the PYNNACLE phase 1/2 study of PC14587, a selective p53 reactivator, in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring a TP53 Y220C mutation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2023, 22 (Suppl. 12), LB_A25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummar, S.; Fellous, M.; Levine, A.J. The roles of mutant p53 in reprogramming and inflammation in breast cancers. Cell Death Differ. 2025, 32, 1949–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.R.; Jones, R.N.; Tareque, R.K.; Springett, N.; Dingler, F.A.; Verduci, L.; Patel, K.J.; Fersht, A.R.; Joerger, A.C.; Spencer, J. A structure-guided molecular chaperone approach for restoring the transcriptional activity of the p53 cancer mutant Y220C. Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 2491–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.H.; Marshall, G.; Yuan, Y.; Steinmaus, C.; Liaw, J.; Smith, M.T.; Wood, L.; Heirich, M.; Fritzemeier, R.M.; Pegram, M.D.; et al. Rapid reduction in breast cancer mortality with inorganic arsenic in drinking water. EBioMedicine 2014, 1, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaram, S.; Synnott, N.C.; Crown, J.; Madden, S.F.; Duffy, M.J. Targeting mutant p53 with arsenic trioxide: A preclinical study focusing on triple negative breast cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 46, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autore, F.; Chiusolo, P.; Sorà, F.; Giammarco, S.; Laurenti, L.; Innocenti, I.; Metafuni, E.; Piccirillo, N.; Pagano, L.; Sica, S. Efficacy and tolerability of first line arsenic trioxide in combination with all-trans retinoic acid in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: Real life experience. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 614721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghadani, R.; Naidu, R. Curcumin: Modulator of key molecular signaling pathways in hormone-independent breast cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, L.; Goyal, H.K.; Jhuria, S.; Dev, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, M.; Kaur, P.; Ethayathulla, A.S. Curcumin rescue p53Y220C in BxPC-3 pancreatic adenocarcinomas cell line: Evidence-based on computational, biophysical, and in vivo studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2021, 1865, 129807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, L.; Sharma, S.; Hariprasad, G.; Dhingra, R.; Mishra, V.; Sharma, R.S.; Kaur, P.; Ethayathulla, A.S. Mechanism of apoptosis activation by curcumin rescued mutant p53Y220C in human pancreatic cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2022, 1869, 119343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, E.; Parker, T.M.; Bauer, M.R.; Dhiman, A.; Pelham, C.J.; Nagane, M.; Kuppusamy, M.L.; Holmes, M.; Holmes, T.R.; Shaik, K.; et al. The curcumin analog HO-3867 selectively kills cancer cells by converting mutant p53 protein to transcriptionally active wildtype p53. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 4262–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Besch-Williford, C.; Hyder, S.M. The estrogen receptor beta agonist liquiritigenin enhances the inhibitory effects of the cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitor RO 48-8071 on hormone-dependent breast-cancer growth. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 192, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Mafuvadze, B.; Hyder, S.M. The estrogen receptor beta agonist liquiritigenin enhances growth inhibition of TNBC by the cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitor RO 48-8071. J. Cancer Sci. Clin. Ther. 2025, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, L.; Kaur, P.; Ethayathulla, A.S. Flavonoids as potential reactivators of structural mutation p53Y220C by computational and cell-based studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 42, 9602–9613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slight, S.H.; Hyder, S.M. Breast Cancer Therapy by Small-Molecule Reactivation of Mutant p53. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120684

Slight SH, Hyder SM. Breast Cancer Therapy by Small-Molecule Reactivation of Mutant p53. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):684. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120684

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlight, Simon H., and Salman M. Hyder. 2025. "Breast Cancer Therapy by Small-Molecule Reactivation of Mutant p53" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120684

APA StyleSlight, S. H., & Hyder, S. M. (2025). Breast Cancer Therapy by Small-Molecule Reactivation of Mutant p53. Current Oncology, 32(12), 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120684