Predictive Relationships Between Death Anxiety and Fear of Cancer Recurrence in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Ethical Statement

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Basic Characteristics

2.4.2. The Templer’s Death Anxiety Scale

2.4.3. The Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Network Analysis

2.5.2. Post Hoc Stability and Accuracy Analysis

2.5.3. Network Comparison

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Death Anxiety and Fear of Recurrence

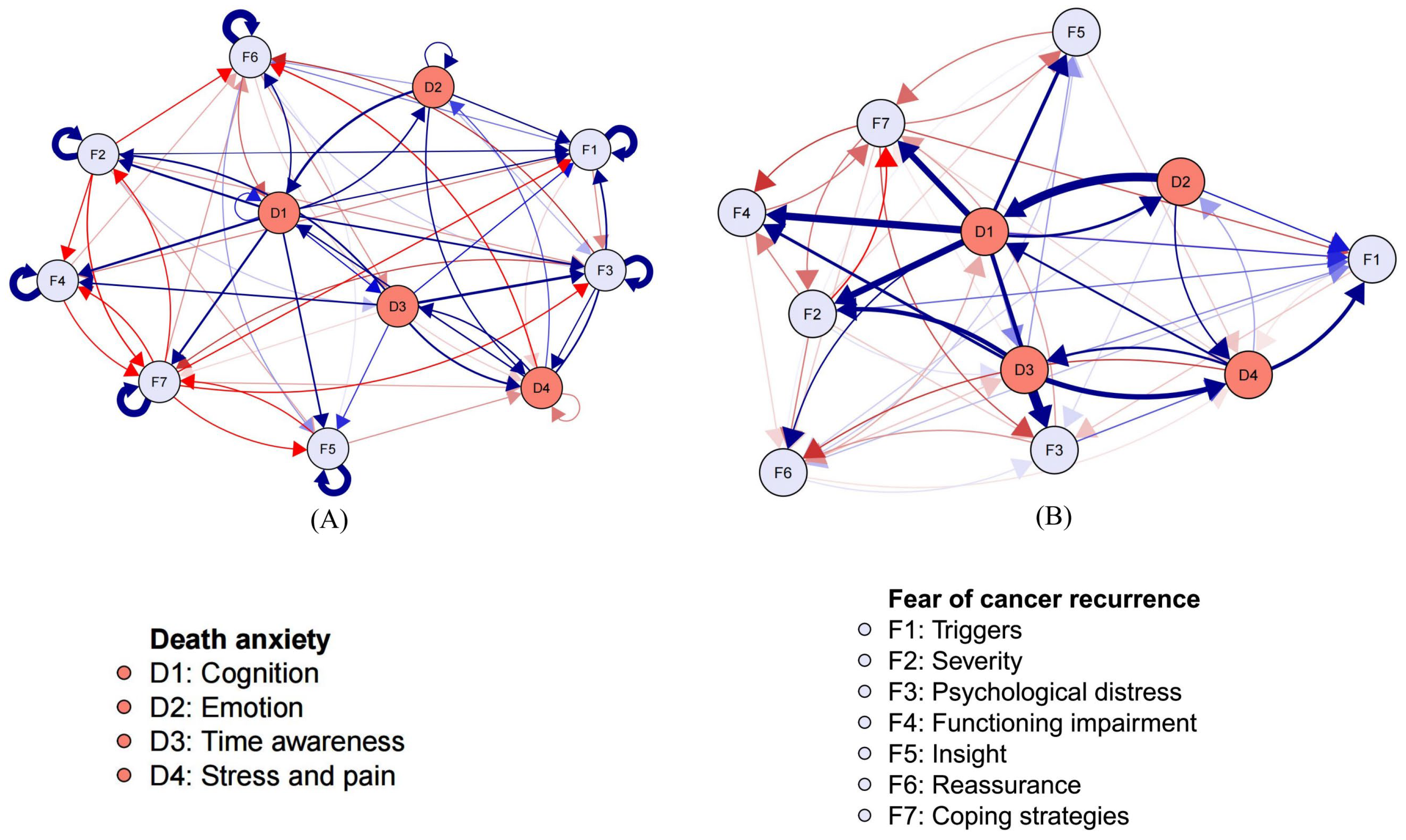

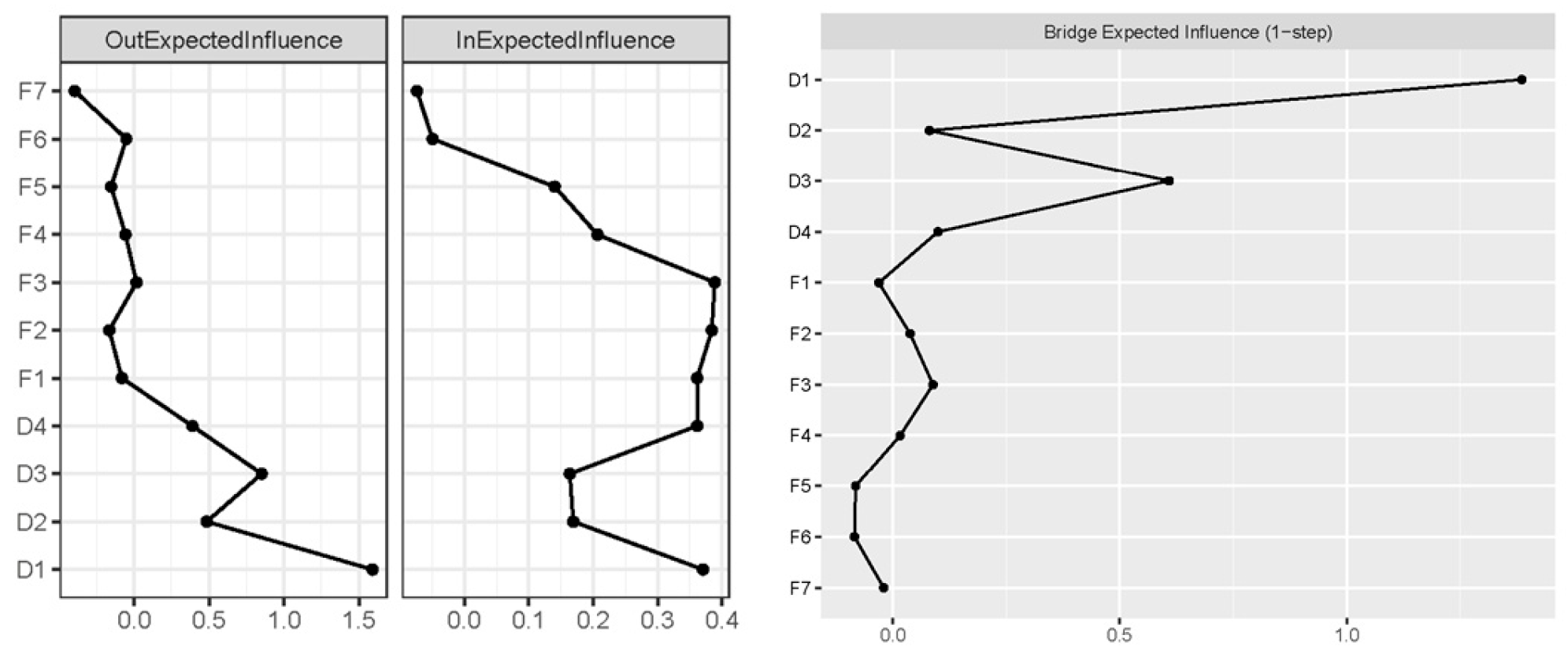

3.3. Cross-Lagged Panel Network Models

3.4. Network Stability and Accuracy

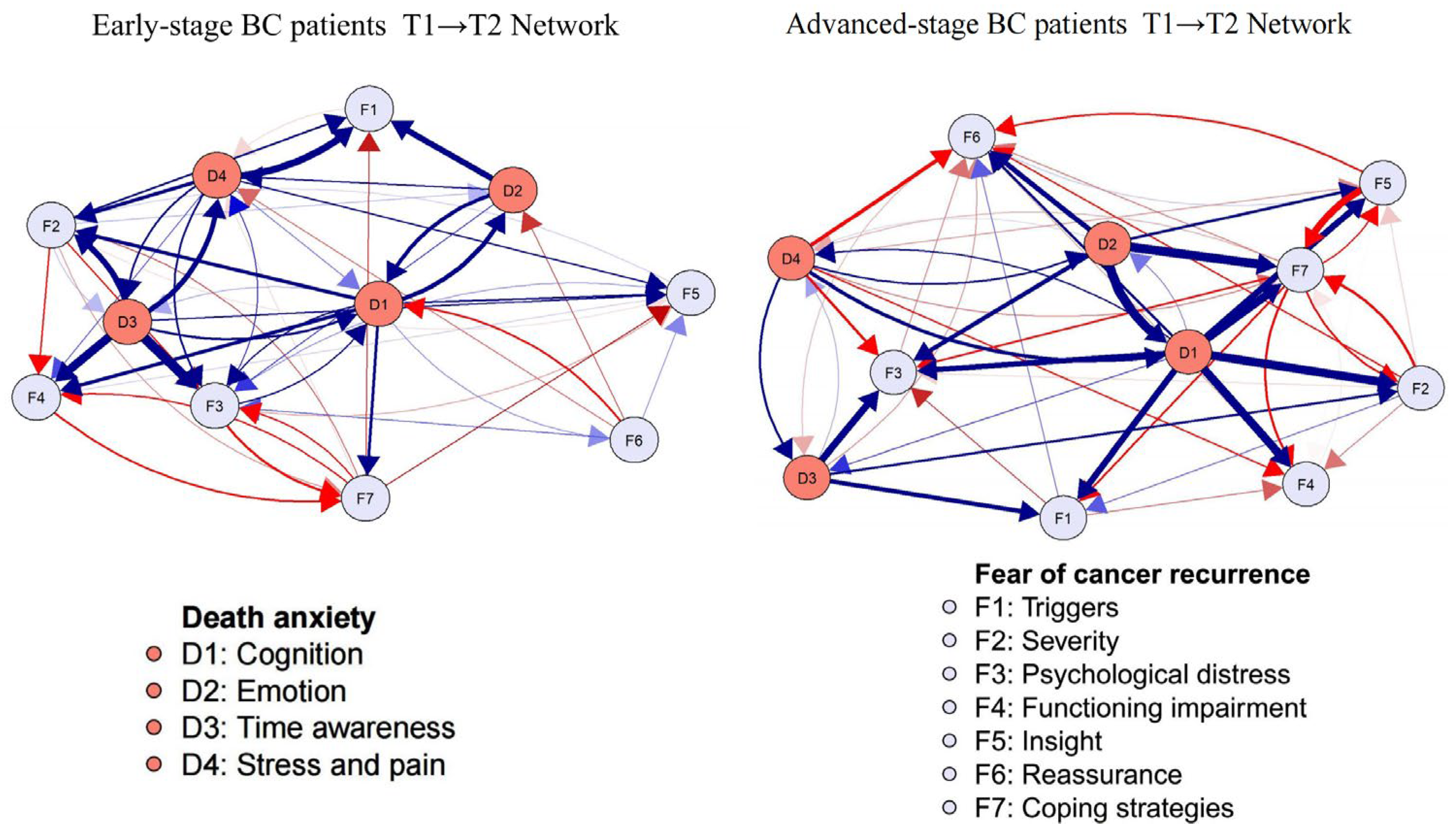

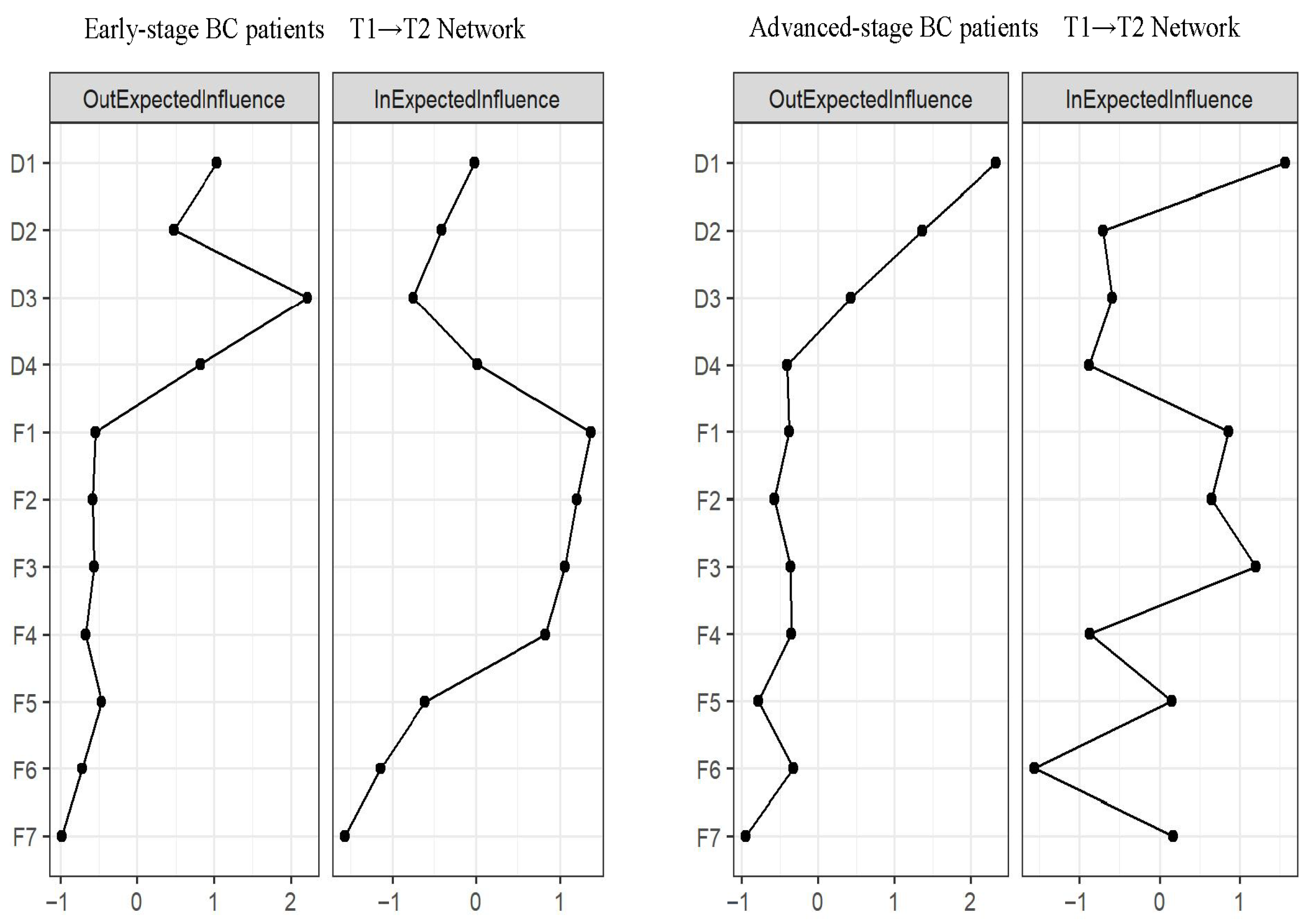

3.5. Network Comparison

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DA | Death anxiety |

| FCR | Fear of cancer recurrence |

| CLPN | Cross-lagged panel networks |

| DIRT | Danger ideation reduction therapy |

References

- Loughan, A.R.; Lanoye, A.; Aslanzadeh, F.J.; Villanueva, A.A.L.; Boutte, R.; Husain, M.; Braun, S. Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Death Anxiety: Unaddressed Concerns for Adult Neuro-oncology Patients. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2021, 28, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampour, S.; Fereidooni-Moghadam, M.; Zarea, K.; Cheraghian, B. The prevalence of death anxiety among patients with breast cancer. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 8, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, L.; Curran, L.; Butow, P.; Thewes, B. Fear of cancer recurrence and death anxiety. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 2559–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, M.A.; Bahrami, N.; Allen, K.A.; Alimoradi, Z. Death anxiety in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 48, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapira, L.; Zheng, Y.; Gelber, S.I.; Poorvu, P.; Ruddy, K.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Peppercorn, J.; Come, S.E.; Borges, V.F.; Partridge, A.H.; et al. Trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer 2022, 128, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.X.M.; Jung, S.Y.; Lee, E.G.; Cho, H.; Kim, N.Y.; Shim, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Kang, D.; Cho, J.; Lee, E.; et al. Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Its Negative Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life in Long-term Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 54, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, L.E.; Siegel, S.D.; Duffy, N.M. Fear of cancer recurrence: A theoretical review and its relevance for clinical presentation and management. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1444–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, L.; Sharpe, L.; MacCann, C.; Butow, P. Testing a model of fear of cancer recurrence or progression: The central role of intrusions, death anxiety and threat appraisal. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 43, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts-Bain, D.; Sharpe, L.; Russell, H. Death anxiety predicts fear of Cancer recurrence and progression in ovarian Cancer patients over and above other cognitive factors. J. Behav. Med. 2023, 46, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellon, S.; Kershaw, T.S.; Northouse, L.L.; Freeman-Gibb, L. A family-based model to predict fear of recurrence for cancer survivors and their caregivers. Psychooncology 2007, 16, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardell, J.E.; Thewes, B.; Turner, J.; Gilchrist, J.; Sharpe, L.; Smith, A.; Girgis, A.; Butow, P. Fear of cancer recurrence: A theoretical review and novel cognitive processing formulation. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, L.; Sharpe, L.; Butow, P. Anxiety in the context of cancer: A systematic review and development of an integrated model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 56, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Ou, M.; Xiao, Z.; Xu, X. The relationship between fear of cancer recurrence and death anxiety among Chinese cancer patients: The serial mediation model. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlin, P.; von Blanckenburg, P. Death anxiety as general factor to fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Xiong, Y.; Li, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Knobf, M.T.; Ye, Z. Association between psychological flexibility and self-perceived burden in patients with cervical cancer: A computer-simulated network analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 74, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, A.; McCarthy, I.; van Bork, R.; Cramer, A.O.J. Cross-lagged panel networks. Adv. Psychol. 2025, 2, e739621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society of Breast Cancer China Anti-Cancer Association; International Medical Exchange Society CAA; Breast Cancer Group BoO; Chinese Medical Doctor Association. Guidelines for clinical diagnosis and treatment of advanced triple negative breast cancer in China (2024 edition). Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2024, 46, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, H.; Xiong, Y.; Knobf, M.T.; Ye, Z. Social support, fear of cancer recurrence and sleep quality in breast cancer: A moderated network analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 74, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Chen, P.; Tang, Y.; Liang, Y.Y.; Li, S.H.; Hu, G.Y.; Sun, Z.; Yu, Y.L.; Molassiotis, A.; Knobf, M.T.; et al. Associations Between Brain Structural Connectivity and 1-Year Demoralization in Breast Cancer: A Longitudinal Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study. Depress. Anxiety 2024, 2024, 5595912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Shen, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Guo, J.; Huang, H.; Knobf, M.T.; Ye, Z. A multi-center study of symptoms in patients with esophageal cancer postoperatively: A networking analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 74, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templer, D.I. The construction and validation of a Death Anxiety Scale. J. Gen. Psychol. 1970, 82, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif Nia, H.; Lehto, R.H.; Pahlevan Sharif, S.; Mashrouteh, M.; Goudarzian, A.H.; Rahmatpour, P.; Torkmandi, H.; Yaghoobzadeh, A. A Cross-Cultural Evaluation of the Construct Validity of Templer’s Death Anxiety Scale: A Systematic Review. Omega 2021, 83, 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Han, L.; Guo, H. Study on the cross-cultural adjustment and application of the Death Anxiety Scale. Chin. J. Pract. Nurs. 2012, 28, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B.; Costa, D.; Galica, J.; Lebel, S.; Tauber, N.; van Helmondt, S.J.; Zachariae, R. Spotlight on the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI). Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, S.; Simard, S.; Harris, C.; Feldstain, A.; Beattie, S.; McCallum, M.; Lefebvre, M.; Savard, J.; Devins, G.M. Empirical validation of the English version of the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funkhouser, C.J.; Chacko, A.A.; Correa, K.A.; Kaiser, A.; Shankman, S.A. Unique longitudinal relationships between symptoms of psychopathology in youth: A cross-lagged panel network analysis in the ABCD study. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelieva, K.; Komulainen, K.; Elovainio, M.; Jokela, M. Longitudinal associations between specific symptoms of depression: Network analysis in a prospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 278, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.J.; Waldorp, L.J. qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Chen, F.; Ou, M.; Xiao, Z.; Xu, X. Trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence and its influence factors: A longitudinal study on Chinese newly diagnosed cancer patients. Psychooncology 2024, 33, e6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuning-Smit, E.; Custers, J.A.E.; Miroševič, Š.; Takes, R.P.; Jansen, F.; Langendijk, J.A.; Terhaard, C.H.J.; Baatenburg de Jong, R.J.; Leemans, C.R.; Smit, J.H.; et al. Prospective longitudinal study on fear of cancer recurrence in patients newly diagnosed with head and neck cancer: Course, trajectories, and associated factors. Head Neck 2022, 44, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, R.H.; Stein, K.F. Death anxiety: An analysis of an evolving concept. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2009, 23, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmanian, K.; Marashian, F.S. Association of Coping Strategies with Death Anxiety through Mediating Role of Disease Perception in Patients with Breast Cancer. Arch. Breast Cancer 2021, 8, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewes, B.; Butow, P.; Bell, M.L.; Beith, J.; Stuart-Harris, R.; Grossi, M.; Capp, A.; Dalley, D.; FCR Study Advisory Committee. Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: A cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 2651–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, E.C.; Valera, R.; Pasipanodya, E.C.; Otto, A.K.; Siegel, S.D.; Laurenceau, J.P. Checking Behavior, Fear of Recurrence, and Daily Triggers in Breast Cancer Survivors. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.M.; Siah, R.C.; Lam, A.S.L.; Cheng, K.K.F. The effect of psychological interventions on fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 3069–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Ou, M.; Xia, W.; Xu, X. Psychological adjustment to death anxiety: A qualitative study of Chinese patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e080220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Khalid, M.A. Death anxiety, perceived social support, and demographic correlates of patients with breast cancer in Pakistan. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haehner, P.; Kritzler, S.; Fassbender, I.; Luhmann, M. Stability and change of perceived characteristics of major life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 122, 1098–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaha, M.; Bauer-Wu, S. Early adulthood uprooted: Transitoriness in young women with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2009, 32, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverach, L.; Menzies, R.G.; Menzies, R.E. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: Reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.P.; Berenbaum, H. Emotional approach and problem-focused coping: A comparison of potentially adaptive strategies. Cogn. Emot. 2007, 21, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Chen, Y.; Gai, Q.; D’Arcy, C.; Su, Y. The co-occurrence between symptoms of internet gaming disorder, depression, and anxiety in middle and late adolescence: A cross-lagged panel network analysis. Addict. Behav. 2025, 161, 108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Classification | Total [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18~44 | 173 (40.61) | |

| 45~59 | 210 (49.30) | |

| ≥60 | 43 (10.09) | |

| Education | ||

| Junior secondary and less | 218 (51.18) | |

| High school/junior college | 140 (32.86) | |

| Bachelor and more | 68 (15.96) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 382 (89.67) | |

| Unmarried/Divorced/widowed | 44 (10.33) | |

| Occupation | ||

| In-service | 350 (82.16) | |

| No occupation | 34 (7.98) | |

| Retirement | 42 (9.86) | |

| Household income (RMB) | ||

| <3000 | 134 (31.46) | |

| 3000~5999 | 141 (33.09) | |

| ≥6000 | 151 (35.45) | |

| Cancer stage | ||

| I | 44 (10.33) | |

| II | 173 (40.61) | |

| III | 168 (39.44) | |

| VII | 41 (9.62) |

| Subscales | Label | Time Point 1 | Time Point 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Cognition | D1 | 3.30 | 2.13 | 2.58 | 1.74 |

| Emotion | D2 | 2.23 | 1.45 | 2.07 | 1.59 |

| Time awareness | D3 | 1.41 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.75 |

| Stress and pain | D4 | 1.98 | 1.18 | 1.19 | 1.23 |

| Triggers | F1 | 14.67 | 6.66 | 13.13 | 5.76 |

| Severity | F2 | 17.40 | 5.34 | 15.37 | 4.68 |

| Psychological distress | F3 | 7.05 | 2.95 | 5.23 | 2.28 |

| Functioning impairment | F4 | 13.58 | 4.53 | 8.93 | 5.41 |

| Insight | F5 | 5.84 | 2.46 | 9.11 | 4.68 |

| Reassurance | F6 | 8.58 | 3.20 | 7.24 | 3.07 |

| Coping strategies | F7 | 17.31 | 7.20 | 15.53 | 9.18 |

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 1.000 | 1.142 | 1.048 | 1.000 | 1.085 | 1.269 | 1.192 | 1.293 | 1.169 | 1.105 | 1.258 |

| D2 | 1.332 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.109 | 1.091 | 1.000 | 1.014 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.020 | 1.000 |

| D3 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.225 | 1.048 | 1.198 | 1.363 | 1.151 | 1.041 | 1.000 | 0.992 |

| D4 | 1.122 | 1.037 | 1.131 | 1.000 | 1.175 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.919 | 1.000 |

| F1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.976 | 0.972 | 1.000 | 1.028 | 1.000 |

| F2 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.012 | 1.000 | 1.063 | 1.000 | 0.978 | 0.949 | 0.981 | 0.947 | 0.896 |

| F3 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.068 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.956 | 0.960 |

| F4 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.983 | 0.941 |

| F5 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.978 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.005 | 0.942 |

| F6 | 0.967 | 1.000 | 0.977 | 0.989 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.011 | 1.000 | 1.022 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| F7 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.981 | 0.929 | 0.944 | 0.928 | 0.920 | 0.943 | 0.979 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, F.; Xiong, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Knobf, M.T.; Ye, Z. Predictive Relationships Between Death Anxiety and Fear of Cancer Recurrence in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120685

Chen F, Xiong Y, Li S, Zhang Q, Deng Y, Xiao Z, Knobf MT, Ye Z. Predictive Relationships Between Death Anxiety and Fear of Cancer Recurrence in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):685. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120685

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Furong, Ying Xiong, Siyu Li, Qihan Zhang, Yiguo Deng, Zhirui Xiao, M. Tish Knobf, and Zengjie Ye. 2025. "Predictive Relationships Between Death Anxiety and Fear of Cancer Recurrence in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120685

APA StyleChen, F., Xiong, Y., Li, S., Zhang, Q., Deng, Y., Xiao, Z., Knobf, M. T., & Ye, Z. (2025). Predictive Relationships Between Death Anxiety and Fear of Cancer Recurrence in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis. Current Oncology, 32(12), 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120685