A Non-Randomized Comparison of Online and In-Person Formats of the Canadian Androgen Deprivation Therapy Educational Program: Impacts on Side Effects, Bother, and Self-Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- assess the effectiveness of the online ADT Educational Program in terms of pre-post changes in self-reported (i) side effect occurrence, (ii) bother associated with side effect experiences, and (iii) sense of self-efficacy to manage side effects;

- compare the effectiveness of the online versus in-person ADT program format based on pre-post changes in participants’ self-reported side effect occurrence, bother, and management self-efficacy;

- examine possible predictors of change in participants’ self-reported side-effect occurrence, bother, and management self-efficacy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Measures

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Baseline and Follow-Up Reports

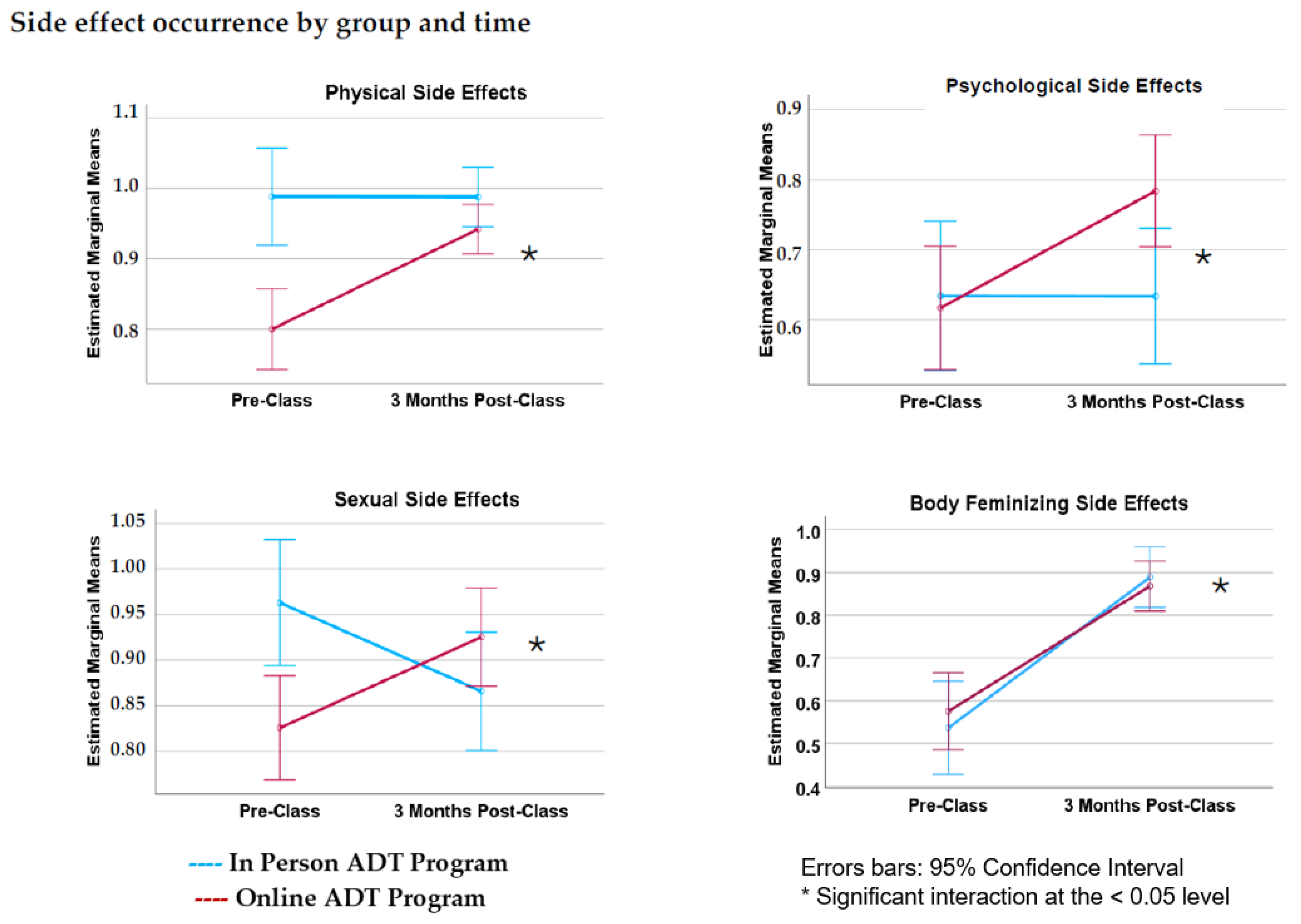

3.3. Side Effect Occurrence

3.4. Side Effect Bother

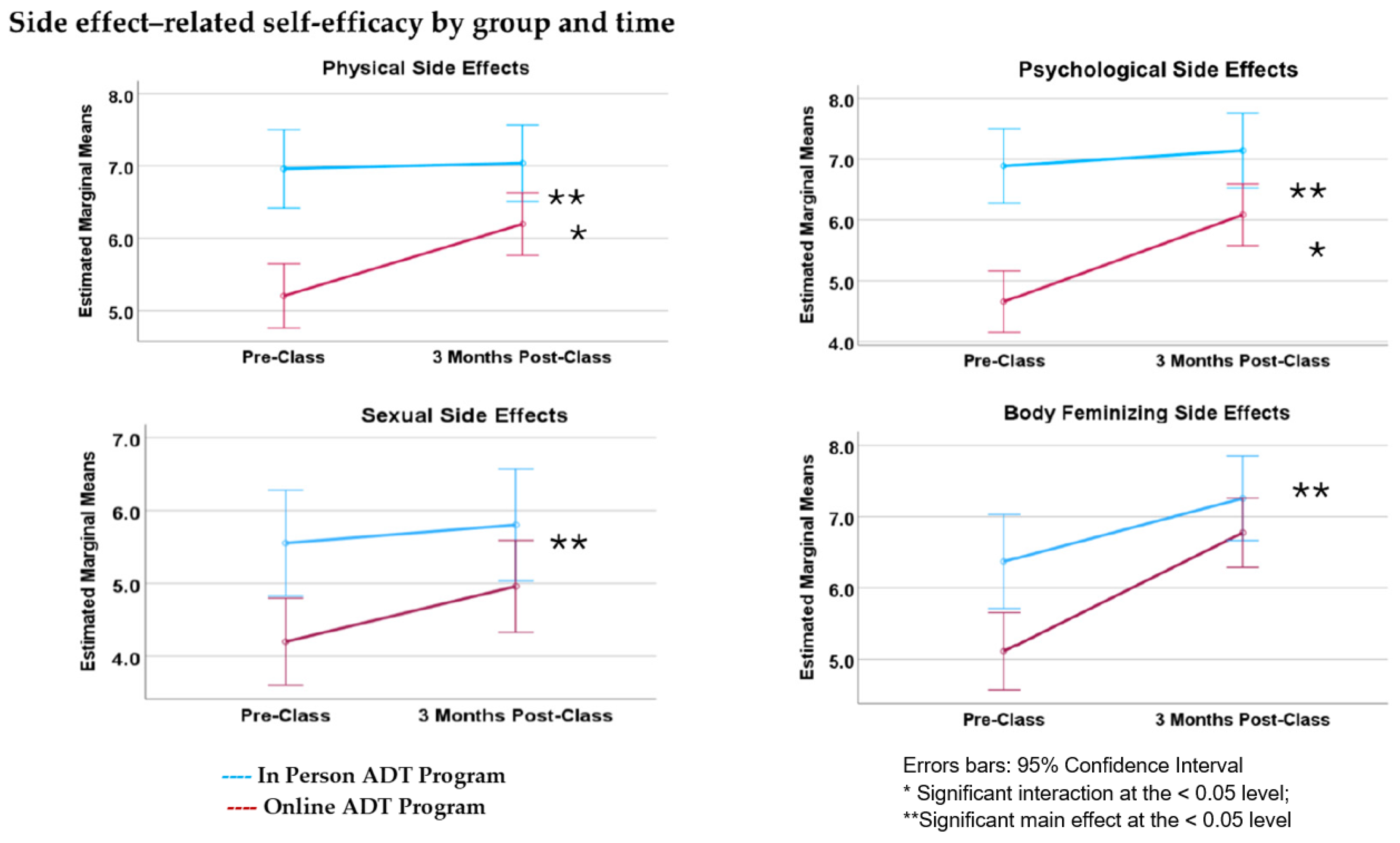

3.5. Side Effect Self-Efficacy

4. Discussion

4.1. Side Effect Occurrence

4.2. Side Effect Bother

4.3. Side Effect Self-Efficacy

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, E.M.; Aragon-Ching, J.B. Advances with androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2022, 23, 1015–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohler, J.L.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Armstrong, A.J.; D’Amico, A.V.; Davis, B.J.; Dorff, T.; Eastham, J.A.; Enke, C.A.; Farrington, T.A.; Higano, C.S.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 479–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liede, A.; Hallett, D.C.; Hope, K.; Graham, A.; Arellano, J.; Shahinian, V.B. International survey of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for non-metastatic prostate cancer in 19 countries. ESMO Open 2016, 1, e000040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokorovic, A.; So, A.I.; Serag, H.; French, C.; Hamilton, R.J.; Izard, J.P.; Nayak, J.G.; Pouliot, F.; Saad, F.; Shayegan, B.; et al. Canadian Urological Association guideline on androgen deprivation therapy: Adverse events and management strategies. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2021, 15, E307–E322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.; Latini, D.M.; Walker, L.M.; Wassersug, R.; Robinson, J.W.; Adt Survivorship Working Group. Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Recommendations to Improve Patient and Partner Quality of Life. J. Sex. Med. 2010, 7, 2996–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, E.; Wassersug, R.J.; Robinson, J.W.; Matthew, A.; McLeod, D.; Walker, L.M. How Are Patients with Prostate Cancer Managing Androgen Deprivation Therapy Side Effects? Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2019, 17, e408–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.M.; Tran, S.; Robinson, J.W. Luteinizing Hormone–Releasing Hormone Agonists: A Quick Reference for Prevalence Rates of Potential Adverse Effects. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2013, 11, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Barocas, D.; Bitting, R.; Bryce, A.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’Amico, A.V.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 1067–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rot, I.; Wassersug, R.J.; Walker, L.M. What do urologists think patients need to know when starting on androgen deprivation therapy? The perspective from Canada versus countries with lower gross domestic product. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2016, 5, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, S.; Walker, L.M.; Wassersug, R.J.; Matthew, A.G.; McLeod, D.L.; Robinson, J.W. What do Canadian uro-oncologists believe patients should know about androgen deprivation therapy? J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 20, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.M.; Tran, S.; Wassersug, R.J.; Thomas, B.; Robinson, J.W. Patients and partners lack knowledge of androgen deprivation therapy side effects. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2013, 31, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibowo, E.; Wassersug, R.J.; Robinson, J.W.; Santos-Iglesias, P.; Matthew, A.; McLeod, D.L.; Walker, L.M. An Educational Program to Help Patients Manage Androgen Deprivation Therapy Side Effects: Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Outcomes. Am. J. Mens. Health 2020, 14, 155798831989899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassersug, R.J.; Walker, L.M.; Robinson, J.W.; Psych, R. Androgen Deprivation Therapy: An Essential Guide for Prostate Cancer Patients and Their Loved Ones, 3rd ed.; Demos Health: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: A consensus approach. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2005, 14, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.P.; Barker, M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 2016, 136, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, C.C.; Finlay, A.; McIntosh, M.; Siddiquee, S.; Short, C.E. A systematic review of the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care interventions targeting men with a history of prostate cancer. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escriva Boulley, G.; Leroy, T.; Bernetière, C.; Paquienseguy, F.; Desfriches-Doria, O.; Préau, M. Digital health interventions to help living with cancer: A systematic review of participants’ engagement and psychosocial effects. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 2677–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, H.; Joubert, L.; Martin-Sanchez, F.; Merolli, M.; Drummond, K.J. A systematic review of types and efficacy of online interventions for cancer patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Kim, H.K.; Park, S.M.; Kim, J.H. Online-based interventions for sexual health among individuals with cancer: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintiliani, L.M.; Mann, D.M.; Puputti, M.; Quinn, E.; Bowen, D.J. Pilot and Feasibility Test of a Mobile Health-Supported Behavioral Counseling Intervention for Weight Management Among Breast Cancer Survivors. JMIR Cancer 2016, 2, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, M.L.; Armbruster, S.; Pohle-Krauza, R.J.; Lyzen, A.M.; Min, S.; Nash, D.W.; Roulette, G.D.; Andrews, S.J.; Von Gruenigen, V.E. Feasibility of a lifestyle intervention for overweight/obese endometrial and breast cancer survivors using an interactive mobile application. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 137, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challapalli, A.; Edwards, S.M.; Abel, P.; Mangar, S.A. Evaluating the prevalence and predictive factors of vasomotor and psychological symptoms in prostate cancer patients receiving hormonal therapy: Results from a single institution experience. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 10, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.T.; Dunn, R.L.; Litwin, M.S.; Sandler, H.M.; Sanda, M.G. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000, 56, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Núñez, J.; Heredia-Ciuró, A.; Valenza-Peña, G.; Granados-Santiago, M.; Hernández-Hernández, S.; Ortiz-Rubio, A.; Valenza, M.C. Systematic review of self-management programs for prostate cancer patients, a quality of life and self-efficacy meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 107, 107583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, C.; Robertson, A.; Smith, A.; Nabi, G. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: A systematic review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafieifar, M.; Hanbidge, A.S.; Lorenzini, S.B.; Macgowan, M.J. Comparative Efficacy of Online vs. Face-to-Face Group Interventions: A Systematic Review. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2024, 10497315241236966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Peña-Purcell, N.C.; Ory, M.G. Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 86, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleras de Frutos, M.; Medina, J.C.; Vives, J.; Casellas-Grau, A.; Marzo, J.L.; Borràs, J.M.; Ochoa-Arnedo, C. Video conference vs. face-to-face group psychotherapy for distressed cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncol. 2020, 29, 1995–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Hormone Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Published 2014. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/treating/hormone-therapy.html (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- McLennan, A.I.G.; Baydoun, M.; Oberoi, D.; Carlson, L.E. “A Hippo Out of Water”: A Qualitative Inquiry of How Cancer Survivors Experienced In-Person and Remote-Delivered Mind-Body Therapies. Glob. Adv. Integr. Med. Health 2023, 12, 27536130231207807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruland, C.M.; Andersen, T.; Jeneson, A.; Moore, S.; Grimsbø, G.H.; Børøsund, E.; Ellison, M.C. Effects of an Internet Support System to Assist Cancer Patients in Reducing Symptom Distress: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2013, 36, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, C.; Grimmett, C.; May, C.M.; Ewings, S.; Myall, M.; Hulme, C.; Smith, P.W.; Powers, C.; Calman, L.; Armes, J.; et al. A web-based intervention (RESTORE) to support self-management of cancer-related fatigue following primary cancer treatment: A multi-centre proof of concept randomised controlled trial. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzer, M.S.; Palmer, S.C.; Kaplan, K.; Brusilovskiy, E.; Ten Have, T.; Hampshire, M.; Metz, J.; Coyne, J.C. A randomized, controlled study of Internet peer-to-peer interactions among women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2010, 19, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, E.; Shinkins, B.; Frith, E.; Neal, D.; Hamdy, F.; Walter, F.; Weller, D.; Wilkinson, C.; Faithfull, S.; Wolstenholme, J.; et al. Symptoms, unmet needs, psychological well-being and health status in survivors of prostate cancer: Implications for redesigning follow-up. BJU Int. 2016, 117, E10–E113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbSPORU. Patient Engagement (PE) Definitions. AbSPORU: Alberta SPOR Support Unit. Published 2024. Available online: https://absporu.ca/patient-engagement/definitions/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

| Variable | In-Person | Online | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Province/Territory (In-Person: n = 94; Online: n = 137) | |||||

| Alberta | 22 | 23.4 | 51 | 37.2 | |

| British Columbia | 46 | 48.9 | 35 | 25.5 | |

| Ontario | 18 | 19.1 | 31 | 22.6 | |

| Atlantic Provinces | 8 | 8.5 | 9 | 6.5 | |

| Saskatchewan | - | - | 5 | 3.6 | |

| Quebec | - | - | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Manitoba | - | - | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Northwest Territories | - | - | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Yukon | - | - | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Ethnicity (In-Person: n = 93; Online: n = 137) | |||||

| White/Caucasian | 79 | 84.0 | 124 | 90.5 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7 | 7.4 | 3 | 2.2 | |

| Black/African-Canadian | 4 | 4.3 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| First Nations/Aboriginal/Native Canadian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Latino/Hispanic/Mexican-Canadian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Middle-Eastern/Arab/Indian | 2 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Other | 1 | 1.1 | - | - | |

| Missing | 1 | 1.1 | - | - | |

| Relationship (In-Person: n = 94; Online: n = 133) | |||||

| Yes | 77 | 81.9 | 121 | 88.3 | |

| No | 17 | 18.1 | 12 | 8.8 | |

| Missing | - | - | 4 | 2.9 | |

| Marital Status (In-Person: n = 93; Online: n = 132) | |||||

| Married/Civil Union | 62 | 66.0 | 104 | 75.9 | |

| Divorced/Separated | 20 | 21.2 | 18 | 13.1 | |

| Never Married | 6 | 6.4 | 8 | 5.8 | |

| Widowed | 5 | 5.3 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1.1 | 5 | 3.6 | |

| Partner’s Gender (In-Person: n = 77; Online: n = 121) 2 | |||||

| Female | 75 | 97.4 | 113 | 93.4 | |

| Male | 2 | 2.6 | 7 | 5.8 | |

| Education (In-Person: n = 94; Online: n = 133) | |||||

| Graduate or professional degree | 44 | 46.8 | 61 | 44.5 | |

| College graduate | 13 | 13.8 | 33 | 24.1 | |

| Some college | 14 | 14.9 | 20 | 14.6 | |

| High school or technical school graduate | 19 | 20.2 | 16 | 11.7 | |

| Less than high school diploma or technical school | 4 | 4.3 | 3 | 2.2 | |

| Missing | - | - | 4 | 2.9 | |

| Employment Status (In-Person: n = 94; Online: n = 133) | |||||

| Retired | 65 | 69.1 | 90 | 65.7 | |

| Part-time | 6 | 6.4 | 21 | 15.3 | |

| Full-time | 20 | 21.3 | 17 | 12.4 | |

| Looking for work | 3 | 3.2 | 5 | 3.6 | |

| Missing | - | - | 4 | 2.9 | |

| Annual Household Income (In-Person: n = 87; Online: n = 127) | |||||

| CAD 30,001–CAD 100,000 | 48 | 51.1 | 77 | 56.2 | |

| More than CAD 100,000 | 28 | 29.8 | 38 | 27.7 | |

| Less than CAD 30,000 | 11 | 11.7 | 12 | 8.8 | |

| Missing | 7 | 7.4 | 10 | 7.3 | |

| PCa Treatment Type | |||||

| ADT injections (Yes) | 78 | 83.0 | 108 | 78.8 | |

| EBRT (Yes) | 27 | 28.7 | 54 | 39.4 | |

| Radical Prostatectomy (Yes) | 42 | 44.7 | 47 | 34.3 | |

| ADT pills (Yes) | 38 | 40.4 | 47 | 34.4 | |

| Active Surveillance (Yes) | 18 | 19.1 | 12 | 8.8 | |

| Brachytherapy (Yes) | 5 | 5.3 | 9 | 6.5 | |

| Cryotherapy (Yes) | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Orchiectomy (Yes) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other (Yes) 1 | - | - | 13 | 9.5 | |

| ADT Started Prior to Class (In-Person: n = 94; Online: n = 136) | |||||

| Yes | 80 | 85.1 | 97 | 70.8 | |

| No | 14 | 14.9 | 39 | 28.5 | |

| Missing | - | - | 1 | 0.7 | |

| M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | ||

| Age (Years) | 68.39 (7.68) | 48–85 | 68.72 (6.59) | 49–84 | |

| Relationship Duration (years) (In-Person: n = 77; Online: n = 121) | 33.99 (16.87) | 0.5–62 | 36.00 (15.46) | 0.6–59 | |

| Duration (days) between baseline and T2 follow-up (In-Person: n = 99, Online: n = 133) | 84.05 (27.23) | 52.00–219.00 | 84.42 (16.05) | 68.53–188.32 | |

| Anticipated duration (number of weeks) between registration form and start of ADT (Online: n = 37) | - | - | 7.65 (11.90) | 0.00–52.00 | |

| Referral Source | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Clinic Nurse/Physician | 40 | 17.3 |

| Support Group/Webinar | 35 | 15.2 |

| Website/Internet Search | 16 | 6.9 |

| Patient/Peer/Friend | 12 | 5.2 |

| Poster/Pamphlet | 10 | 4.3 |

| Program Facilitator | 6 | 2.6 |

| Psychosocial Oncology Clinician | 3 | 1.3 |

| Pharmacy | 3 | 1.3 |

| ADT Book | 3 | 1.3 |

| Prostate Cancer Centre | 3 | 1.3 |

| Organization Newsletter | 1 | 0.4 |

| Other | 1 | 0.4 |

| Missing | 98 | 42.4 |

| Total | 231 | 100.0 |

| Outcome | F | df | p Value | Partial Eta Squared | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side effect occurrence scores | ||||||

| In-person vs. online | 5.500 | 1, 199 | <0.001 | 0.101 | ||

| Body Feminization | 0.035 | 1, 199 | 0.852 | 0.000 | ||

| Physical | 14.376 | 1, 199 | <0.001 | 0.067 | ||

| Emotional | 1.346 | 1, 199 | 0.247 | 0.007 | ||

| Sexual | 1.479 | 1, 199 | 0.225 | 0.007 | ||

| Pre-class vs. post-class | 2.032 | 1, 199 | 0.091 | 0.040 | ||

| Body Feminization | 5.330 | 1, 199 | 0.022 | 0.026 | ||

| Physical | 1.389 | 1, 199 | 0.240 | 0.007 | ||

| Emotional | 0.652 | 1, 199 | 0.421 | 0.003 | ||

| Sexual | 0.133 | 1, 199 | 0.716 | 0.001 | ||

| Side effect bother | ||||||

| In-person vs. online | 2.216 | 1, 212 | 0.068 | 0.041 | ||

| Body Feminization | 0.914 | 1, 212 | 0.340 | 0.004 | ||

| Physical | 0.387 | 1, 212 | 0.535 | 0.002 | ||

| Emotional | 1.808 | 1, 212 | 0.180 | 0.008 | ||

| Sexual | 2.358 | 1, 212 | 0.126 | 0.011 | ||

| Pre-class vs. post-class | 4.572 | 1, 212 | 0.001 | 0.080 | ||

| Body Feminization | 11.749 | 1, 212 | <0.001 | 0.053 | ||

| Physical | 12.255 | 1, 212 | <0.001 | 0.055 | ||

| Emotional | 0.940 | 1, 212 | 0.333 | 0.004 | ||

| Sexual | 1.080 | 1, 212 | 0.300 | 0.005 | ||

| Side effect self-efficacy | ||||||

| In-person vs. online | 7.059 | 1, 193 | <0.001 | 0.129 | ||

| Body Feminization | 6.238 | 1, 193 | 0.013 | 0.031 | ||

| Physical | 18.585 | 1, 193 | <0.001 | 0.088 | ||

| Emotional | 21.703 | 1, 193 | <0.001 | 0.101 | ||

| Sexual | 6.349 | 1, 193 | 0.013 | 0.032 | ||

| Pre-class vs. post-class | 1.313 | 1, 193 | 0.267 | 0.027 | ||

| Body Feminization | 2.157 | 1, 193 | 0.144 | 0.011 | ||

| Physical | 0.030 | 1, 193 | 0.862 | 0.000 | ||

| Emotional | 0.743 | 1, 193 | 0.390 | 0.004 | ||

| Sexual | 0.419 | 1, 193 | 0.518 | 0.002 | ||

| In Person | Online | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | |||||||||

| Occurrence—Yes | Bother * | Self-Efficacy | Occurrence—Yes | Bother * | Self-Efficacy | Occurrence—Yes | Bother * | Self-Efficacy | Occurrence—Yes | Bother * | Self-Efficacy | |

| Side Effect | N (%) | M (SD) | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | M (SD) | N (%) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Erectile difficulties | 75 (79.8) | 40.73 (41.52) | 5.27 (2.77) | 71 (75.5) | 38.33 (43.09) | 5.74 (3.19) | 101 (73.7) | 46.76 (40.12) | 4.07 (3.80) | 120 (87.6) | 51.53 (38.45) | 4.96 (3.79) |

| Loss of libido | 56 (59.6) | 52.78 (38.84) | 5.67 (2.77) | 31 (33.0) | 47.22 (41.47) | 5.78 (3.20) | 87 (63.5) | 54.04 (39.96) | 4.20 (3.68) | 115 (83.9) | 52.07 (37.69) | 4.85 (3.77) |

| Fatigue | 78 (83) | 64.89 (35.42) | 6.42 (2.28) | 71 (75.5) | 50.00 (33.54) | 6.86 (2.20) | 84 (61.3) | 58.71 (37.70) | 4.82 (3.31) | 100 (73.0) | 50.95 (33.61) | 5.80 (3.20) |

| Change in genital size | 31 (33) | 82.88 (29.17) | 6.36 (2.45) | 51 (54.3) | 75.27 (32.38) | 6.61 (2.69) | 49 35.8) | 83.40 (29.19) | 4.35 (3.75) | 86 (62.8) | 77.07 (29.68) | 5.32 (3.83) |

| Weight gain | 26 (27.7) | 80.00 (29.56) | 7.61 (2.05) | 43 (45.7) | 72.22 (32.98) | 7.61 (1.90) | 38 (27.7) | 81.30 (30.44) | 6.08 (3.01) | 60 (43.8) | 71.80 (33.06) | 6.94 (2.76) |

| Muscle loss | 24 (25.5) | 84.51 (28.19) | 7.17 (2.16) | 45 (47.9) | 71.70 (30.32) | 7.39 (1.88) | 41 (29.9) | 77.36 (33.69) | 5.45 (3.18) | 65 (47.4) | 66.03 (35.23) | 6.50 (3.03) |

| Relationship strain | 20 (21.3) | 80.75 (28.45) | 6.83 (2.45) | 25 (26.6) | 82.95 (25.86) | 7.29 (2.37) | 23 (16.8) | 81.68 (30.04) | 5.84 (3.79) | 30 (21.9) | 80.45 (29.89) | 6.76 (3.42) |

| Loss of body hair | 13 (13.8) | 93.01 (19.63) | - | 27 (28.7) | 93.68 (16.07) | - | 22 (16.1) | 93.55 (18.89) | - | 42 (30.7) | 90.79 (21.64) | - |

| Breast enlargement | 13 (13.8) | 91.13 (20.74) | 5.88 (2.78) | 25 (26.6) | 87.09 (23.97) | 7.13 (2.33) | 26 (19) | 91.15 (20.38) | 5.02 (3.88) | 32 (23.4) | 89.77 (21.39) | 6.62 (3.51) |

| Hot flashes | 52 (55.3) | 65.69 (37.02) | 6.82 (2.45) | 80 (85.1) | 49.45 (31.40) | 7.53 (2.23) | 71 (51.8) | 68.18 (36.82) | 5.39 (3.46) | 106 (77.4) | 56.53 (32.72) | 6.65 (3.09) |

| Emotional expression | 33 (35.1) | 84.41 (21.47) | 6.91 (2.11) | 32 (34.0) | 76.37 (27.22) | 7.24 (2.11) | 56 (40.9) | 78.85 (29.61) | 4.88 (3.30) | 72 (52.6) | 73.68 (28.92) | 6.16 (3.31) |

| Depression | 32 (34) | 83.97 (26.62) | 6.91 (2.08) | 38 (40.4) | 79.67 (28.60) | 7.19 (2.19) | 28 (20.4) | 81.54 (29.79) | 4.89 (3.41) | 51 (37.2) | 77.84 (29.08) | 6.40 (3.26) |

| Cardiovascular disease ** | - | 90.76 (23.65) | 6.86 (2.15) | - | 87.36 (26.10) | 7.36 (1.97) | - | 90.96 (24.51) | 4.98 (3.71) | - | 88.95 (24.79) | 6.49 (3.24) |

| Diabetes ** | - | 92.93 (21.07) | 6.79 (2.25) | - | 90.45 (23.08) | 7.32 (1.97) | - | 89.92 (25.49) | 5.25 (3.61) | - | 90.96 (21.11) | 6.79 (3.24) |

| Breast Tenderness | 7 (7.4) | 94.02 (16.31) | 6.18 (2.61) | 9 (9.6) | 93.24 (16.54) | 7.20 (2.32) | 10 (7.3) | 94.19 (16.09) | 5.41 (3.92) | 13 (9.5) | 94.66 (16.70) | 7.04 (3.45) |

| Memory | 38 (40.4) | 83.97 (25.30) | 6.88 (1.96) | 43 (45.7) | 78.02 (27.09) | 7.16 (2.01) | 52 (38) | 81.15 (27.33) | 4.25 (3.47) | 72 (52.6) | 75.75 (27.69) | 5.74 (3.48) |

| Bone Density Loss | - | 89.24 (25.59) | 6.18 (2.48) | - | 86.25 (23.83) | 6.95 (2.19) | - | 89.48 (26.71) | 4.95 (3.37) | - | 85.74 (25.04) | 6.13 (3.26) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walker, L.M.; Sears, C.S.; Wibowo, E.; Robinson, J.W.; Matthew, A.G.; McLeod, D.L.; Wassersug, R.J. A Non-Randomized Comparison of Online and In-Person Formats of the Canadian Androgen Deprivation Therapy Educational Program: Impacts on Side Effects, Bother, and Self-Efficacy. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 5040-5056. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31090373

Walker LM, Sears CS, Wibowo E, Robinson JW, Matthew AG, McLeod DL, Wassersug RJ. A Non-Randomized Comparison of Online and In-Person Formats of the Canadian Androgen Deprivation Therapy Educational Program: Impacts on Side Effects, Bother, and Self-Efficacy. Current Oncology. 2024; 31(9):5040-5056. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31090373

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalker, Lauren M., Carly S. Sears, Erik Wibowo, John W. Robinson, Andrew G. Matthew, Deborah L. McLeod, and Richard J. Wassersug. 2024. "A Non-Randomized Comparison of Online and In-Person Formats of the Canadian Androgen Deprivation Therapy Educational Program: Impacts on Side Effects, Bother, and Self-Efficacy" Current Oncology 31, no. 9: 5040-5056. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31090373

APA StyleWalker, L. M., Sears, C. S., Wibowo, E., Robinson, J. W., Matthew, A. G., McLeod, D. L., & Wassersug, R. J. (2024). A Non-Randomized Comparison of Online and In-Person Formats of the Canadian Androgen Deprivation Therapy Educational Program: Impacts on Side Effects, Bother, and Self-Efficacy. Current Oncology, 31(9), 5040-5056. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31090373