Perspectives and Misconceptions of an Online Adult Male Cohort Regarding Prostate Cancer Screening

Abstract

1. Key Messages

- ○

- have low knowledge and possess misconceptions about prostate cancer and screening;

- ○

- are interested in screening for prostate cancer, including PSA;

- ○

- want to be included in shared decision-making for prostate cancer screening;

- ○

- accept the negative trade-offs associated with screening, including unnecessary testing and treatment.

1.1. Social Media Blurb

1.2. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

2.2. Survey Distribution

2.3. Study Sample

2.4. Comparative Cohort

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Prostate Cancer Knowledge

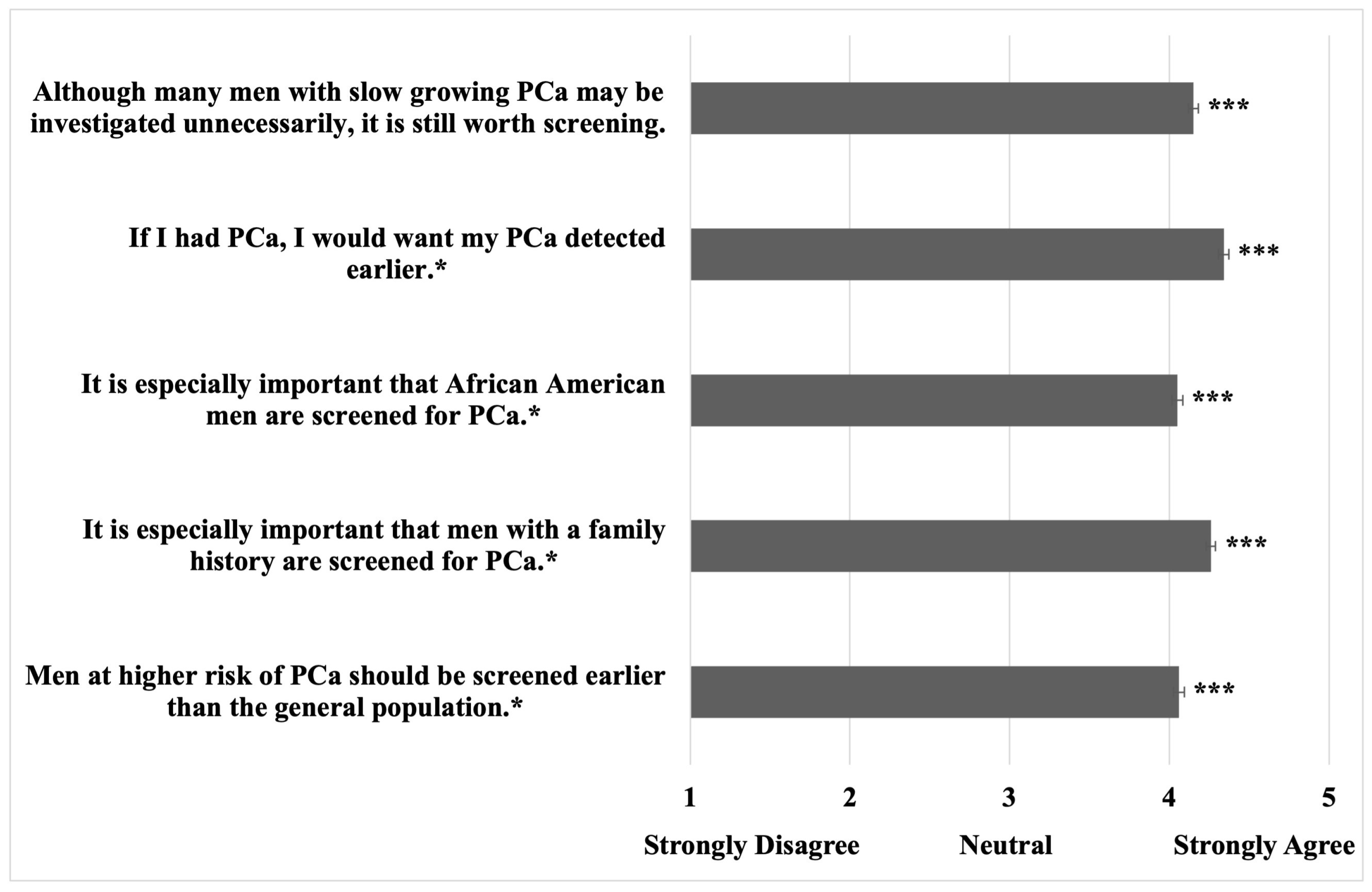

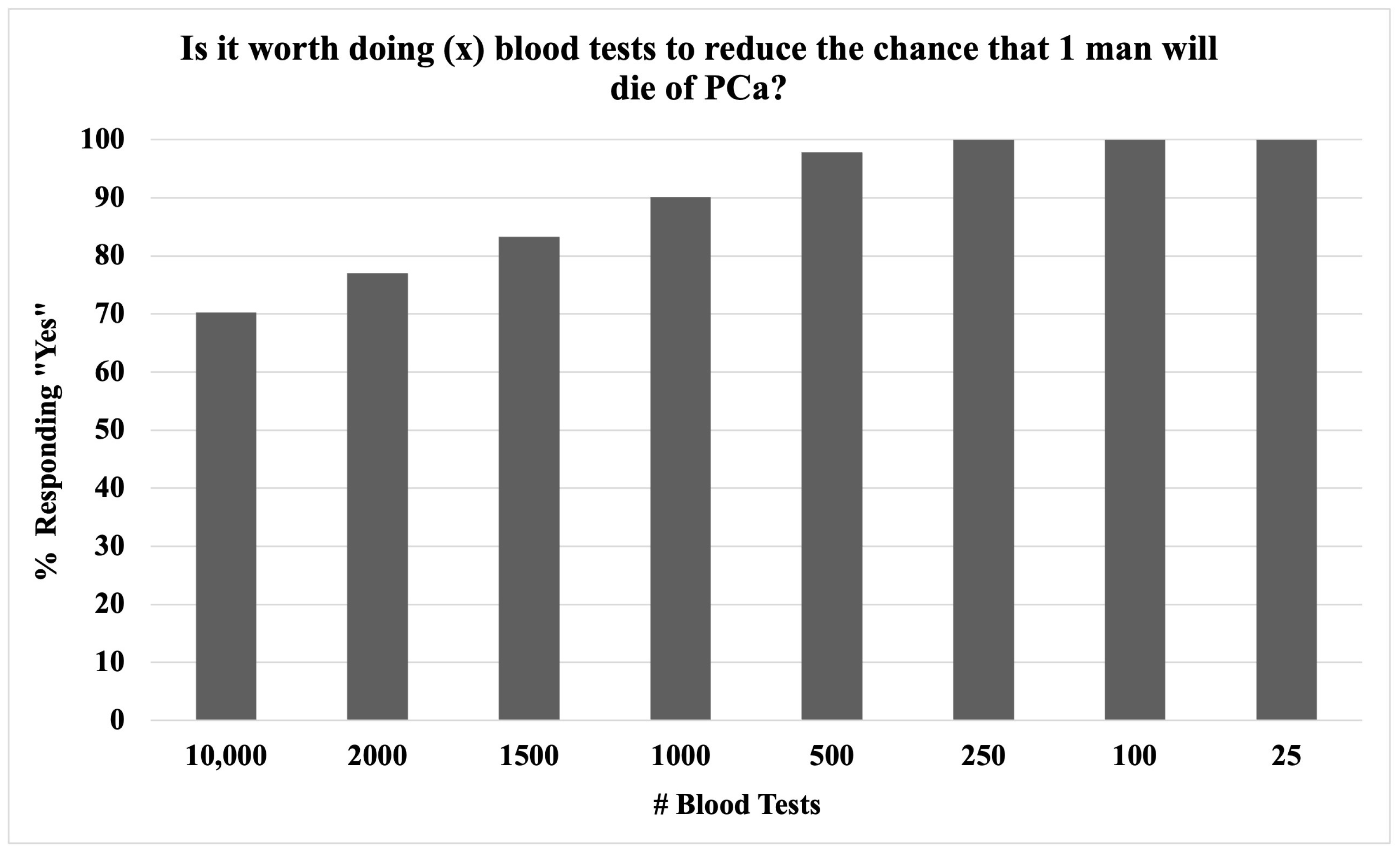

3.3. Prostate Cancer Screening Attitudes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andriole, G.L.; Crawford, E.D.; Grubb, R.L.I.; Buys, S.S.; Chia, D.; Church, T.R.; Fouad, M.N.; Gelmann, E.P.; Kvale, P.A.; Reding, D.J.; et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared decision making—The pinnacle of patient-centered care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe, S.; Scimeca, A.; Diab, D.; Wong, N.C.; Posid, T.; Dason, S. Testicular Cancer Knowledge and Viewpoints of American Men. Urol. Pract. 2022, 9, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, B. The Patient Experience and Patient Satisfaction: Measurement of a Complex Dynamic. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2016, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, U.S.C. Unites States Census Quick Facts. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221 (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Evans, W.D.; Lantz, P.M.; Mead, K.; Alvarez, C.; Snider, J. Adherence to clinical preventive services guidelines: Population-based online randomized trial. SSM Popul. Health 2015, 1, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, J.M.; Shaw, E.K.; Scott, J.G. Factors influencing men’s decisions regarding prostate cancer screening: A qualitative study. J. Community Health 2011, 36, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gejerman, G.; Ciccone, P.; Goldstein, M.; Lanteri, V.; Schlecker, B.; Sanzone, J.; Esposito, M.; Rome, S.; Ciccone, M.; Margolis, E.; et al. US Preventive Services Task Force prostate-specific antigen screening guidelines result in higher Gleason score diagnoses. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2017, 58, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomella, L.G.; Liu, X.S.; Trabulsi, E.J.; Kelly, W.K.; Myers, R.; Showalter, T.; Dicker, A.; Wender, R. Screening for Prostate Cancer: The Current Evidence and Guidelines Controversy. Can. J. Urol. 2011, 18, 5875–5883. [Google Scholar]

- Force, U.P.S.T.; Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Owens, D.K.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Ebell, M.; Epling, J.W.; et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer. JAMA 2018, 319, 1901–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.K.J.; Kobrin, S.; Breen, N.; Joseph, D.A.; Li, J.; Frosch, D.L.; Klabunde, C.N. National evidence on the use of shared decision making in prostate-specific antigen screening. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevey, D.; Pertl, M.; Thomas, K.; Maher, L.; Chuinneagáin, S.N.; Craig, A. The relationship between prostate cancer knowledge and beliefs and intentions to attend PSA screening among at-risk men. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Fedewa, S.A.; Wen, Y.; Jemal, A.; Han, X. Shared decision making and prostate-specific antigen based prostate cancer screening following the 2018 update of USPSTF screening guideline. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021, 24, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leapman, M.S.; Wang, R.; Park, H.; Yu, J.B.; Sprenkle, P.C.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Gross, C.P.; Ma, X. Changes in Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing Relative to the Revised US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation on Prostate Cancer Screening. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 8, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.H.; Kong, T.; Killow, V.; Wang, L.; Kobes, K.; Tekian, A.; Ingledew, P.-A. Quality Assessment of Online Resources for the Most Common Cancers. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 38, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, R.J.; Marzouk, K.; Finelli, A.; Saad, F.; So, A.I.; Violette, P.D.; Breau, R.H.; Rendon, R.A. UPDATE—2022 Canadian Urological Association recommendations on prostate cancer screening and early diagnosis: Endorsement of the 2021 Cancer Care Ontario guidelines on prostate multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2022, 16, E184–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, M.E.; Occhipinti, S.; Chambers, S.K. Classifying the reasons men consider to be important in prostate-specific antigen (psa) testing decisions: Evaluating risks, lay beliefs, and informed decisions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.C. A discussion on controversies and ethical dilemmas in prostate cancer screening. J. Med. Ethic 2020, 47, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Trinh, Q.; Cole, A.P.; Kilbridge, K.L.; Mahal, B.A.; Hayn, M.; Hansen, M.; Han, P.K.J.; Sammon, J.D. Impact of health literacy on shared decision making for prostate-specific antigen screening in the United States. Cancer 2021, 127, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orom, H.; Underwood, W.; Homish, D.L.; Kiviniemi, M.T.; Homish, G.G.; Nelson, C.J.; Schiffman, Z. Prostate cancer survivors’ beliefs about screening and treatment decision-making experiences in an era of controversy. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsky, P.F.; Black, A.; Kramer, B.S.; Miller, A.; Prorok, P.C.; Berg, C. Assessing contamination and compliance in the prostate component of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Clin. Trials 2010, 7, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheetz, T.; Amin, S.; Diab, D.; Payne, N.; Posid, T. Current Knowledge and Opinions of Medical Trainees Regarding PSA Screening. J. Cancer Educ. 2022, 37, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shungu, N.; Haley, S.P.; Berini, C.R.; Foster, D.; Diaz, V.A. Quality of YouTube Videos on Prostate Cancer Screening for Black Men. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021, 34, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squiers, L.B.; Bann, C.M.; Dolina, S.E.; Tzeng, J.; McCormack, L.; Kamerow, D. Prostate-specific antigen testing: Men’s responses to 2012 recommendation against screening. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamey, T.A.; Yang, N.; Hay, A.R.; McNeal, J.E.; Freiha, F.S.; Redwine, E. Prostate-specific antigen as a serum marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.; Glasziou, P.; Rychetnik, L.; Mackenzie, G.; Gardiner, R.; Doust, J. Deliberative democracy and cancer screening consent: A randomised control trial of the effect of a community jury on men’s knowledge about and intentions to participate in PSA screening. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vines, A.I.; Hunter, J.C.; Carlisle, V.A.; Richmond, A.N. rostate Cancer Ambassadors: Process and Outcomes of a Prostate Cancer Informed Decision-Making Training Program. Am. J. Men’s Health 2017, 11, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Barocas, D.; Carlsson, S. Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline (2023)—American Urological Association. 2023, 1–47. Available online: https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/early-detection-of-prostate-cancer-guidelines (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Weiner, A.B.; Matulewicz, R.S.; E Eggener, S.; Schaeffer, E.M. Increasing incidence of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States (2004–2013). Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016, 19, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Myrie, A.; Taylor, J.I.; Matulewicz, R.; Gao, T.; Pérez-Rosas, V.; Mihalcea, R.; Loeb, S. Instagram and prostate cancer: Using validated instruments to assess the quality of information on social media. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021, 25, 791–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics (n = 906) | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

| Age (years) 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–69 70–79 | 38.2 (12.0) 226 (24.9%) 333 (36.8%) 200 (22.1%) 77 (8.5%) 52 (5.7%) 14 (1.5%) |

| Married Status | 498 (55.0%) |

| Median Yearly Household Income Category | USD 50,000–74,999 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 619 (68.3%) |

| Asian | 151 (16.8%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 150 (16.6%) |

| Black | 88 (9.8%) |

| Other | 21 (2.3%) |

| Highest Degree Level | |

| Less than a secondary school degree | 4 (0.4%) |

| Secondary school degree (or equivalent) | 174 (19.2%) |

| Associate degree | 58 (6.4%) |

| Bachelor degree | 491 (54.2%) |

| Professional degree (e.g., J.D. or M.D.) | 47 (5.2%) |

| Graduate degree (e.g., Ph.D.) | 115 (12.7%) |

| General Health Descriptors | |

| Healthcare worker | 266 (29.4%) |

| Current health self-rating (1–10 Likert scale) | 7.4 (1.74) |

| Current smoker | 247 (27.3%) |

| Prostate Health Descriptors | |

| Ever received PSAS? | 181 (20.0%) |

| Ever received DRE screening? | 227 (25.1%) |

| Ever been told your PSA was elevated? | 152 (16.8%) |

| Ever received PCa diagnostic testing? | 149 (16.4%) |

| Ever been diagnosed with PCa? | 64 (7.1%) |

| Ever had a family member diagnosed with PCa? | 201 (22.2%) |

| Ever had a family member die from PCa? | 113 (12.4%) |

| 2a. Self-Reported Prostate Cancer Knowledge. | |

|---|---|

| Survey Question | Affirmative Answer, n (%) |

| Do you know… | |

| …what a prostate is? | 768 (84.8%) |

| …that men can get PCa? | 773 (85.3%) |

| …that men can get screened for PCa? | 733 (80.9%) |

| …how men get screened for prostate cancer? | 538 (59.4%) |

| Do you possess little or no knowledge about… | |

| …PCa? | 361 (39.8%) |

| …PSAS guidelines? | 574 (63.3%) |

| 2b. Prostate Cancer and PSA Multiple-Choice Knowledge Assessment. | |

| Assessment Question | Correct Answer, n (%) |

| Is PCa treatable? | 672 (74.2%) |

| What are the side effects of PCa treatment? | 421 (46.5%) |

| How common is PCa? | 315 (34.8%) |

| Which age group is most likely to develop PCa? | 234 (25.8%) |

| Does all PCa require treatment? | 196 (21.6%) |

| Is PCa fatal? | 549 (60.9%) |

| Average correct | 44.00% |

| Misconceptions Regarding Prostate Cancer (PCa) Among Middle-Aged Men | ||

|---|---|---|

| Survey Question | Incorrect Answers | n (%) |

| Does all PCa require treatment? | Yes | 644 (71%) |

| What age group is most likely to get PCa? | 41–60 | 416 (46%) |

| 21–40 | 154 (17%) | |

| 0–20 | 10 (1%) | |

| How common is PCa? | Top 5 male cancer | 373 (41%) |

| Rare | 128 (14%) | |

| Top 20 male cancer | 81 (9%) | |

| Chance a man will develop PCa in his life? | Pretty low chance | 209 (30%) |

| Very low chance | 113 (16%) | |

| Is PCa fatal? | Usually | 182 (20%) |

| Always | 60 (7%) | |

| Never | 66 (7%) | |

| Can men get screened for PCa? | No | 164 (18%) |

| Can men get PCa? | No | 122 (14%) |

| Is PCa treatable? | Always | 121 (13%) |

| No | 77 (9%) | |

| Prostate Cancer and PSA Screening: Perspectives and Preferences | ||

|---|---|---|

| Survey Question | Affirmative Answer, n(%) | |

| Has your doctor talked to you about PCa? | ||

| No | 526 (58.1%) | |

| Once | 239 (26.4%) | |

| More than once | 115 (12.7%) | |

| Would you like your doctor to talk to you about PCa? | ||

| No | 262 (28.9%) | |

| Regularly | 251 (27.7%) | |

| One time | 244 (26.9%) | |

| Already do/did | 118 (13.0%) | |

| Would you feel upset if your Dr. did not talk to you about PCa? | 276 (30.5%) | |

| If screening existed, * would you… | ||

| want your Dr. to discuss it with you? | 668 (73.7%) | |

| be upset if your Dr. did not discuss it with you? | 561 (61.9%) | |

| If I was diagnosed with PCa, this would cause me distress. | 700 (77.3%) | |

| Who should make the decision about whether or not a patient should have a PSA test? | ||

| Provider and patient together | 442 (48.8%) | |

| Patient | 230 (25.4%) | |

| I do not know | 141 (15.6%) | |

| Provider | 93 (10.3%) | |

| Do you still think it is worth screening for PCa if… | ||

| …PSAS could lead to side effects and even unnecessary treatment? * | ||

| Yes – always | 372 (41.1%) | |

| Yes – for high-risk patients | 305 (33.7%) | |

| It depends on the number helped vs. harmed | 139 (15.3%) | |

| No | 46 (5.1%) | |

| …PCa treatment could cause erectile dysfunction? | ||

| Yes | 669 (73.9%) | |

| No | 172 (19.0%) | |

| …PCa treatment could cause urinary problems (e.g., leakage)? | ||

| Yes | 676 (74.6%) | |

| No | 166 (18.3%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheetz, T.; Posid, T.; Khuhro, A.; Scimeca, A.; Beebe, S.; Gul, E.; Dason, S. Perspectives and Misconceptions of an Online Adult Male Cohort Regarding Prostate Cancer Screening. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 6395-6405. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31100475

Sheetz T, Posid T, Khuhro A, Scimeca A, Beebe S, Gul E, Dason S. Perspectives and Misconceptions of an Online Adult Male Cohort Regarding Prostate Cancer Screening. Current Oncology. 2024; 31(10):6395-6405. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31100475

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheetz, Tyler, Tasha Posid, Aliza Khuhro, Alicia Scimeca, Sarah Beebe, Essa Gul, and Shawn Dason. 2024. "Perspectives and Misconceptions of an Online Adult Male Cohort Regarding Prostate Cancer Screening" Current Oncology 31, no. 10: 6395-6405. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31100475

APA StyleSheetz, T., Posid, T., Khuhro, A., Scimeca, A., Beebe, S., Gul, E., & Dason, S. (2024). Perspectives and Misconceptions of an Online Adult Male Cohort Regarding Prostate Cancer Screening. Current Oncology, 31(10), 6395-6405. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31100475