Cost Drivers and Financial Burden for Cancer-Affected Families in China: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Search Strategy

2.2. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment of Included Studies

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

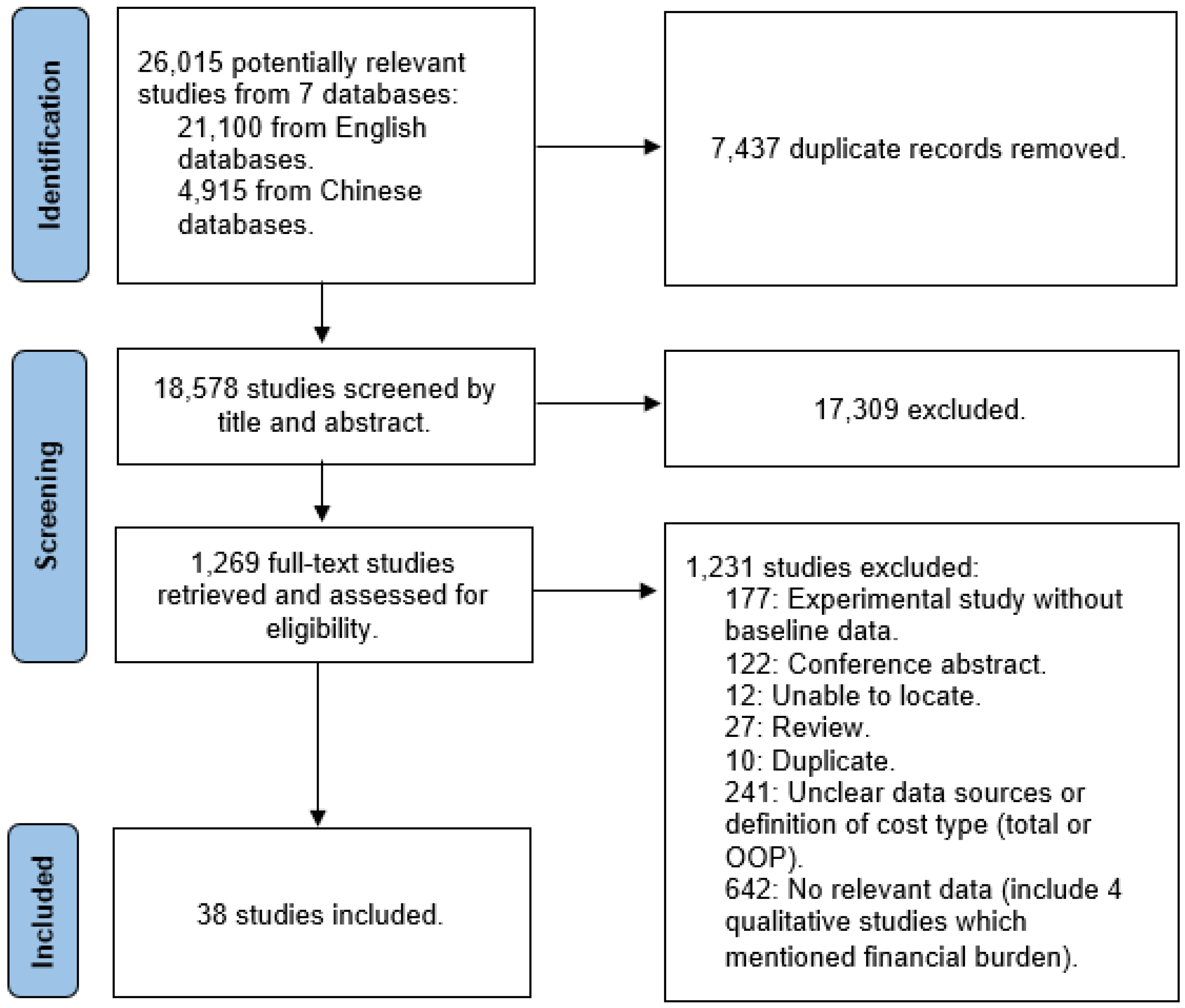

3.1. Study Identification and Main Characteristics of the Studies

3.2. Distribution of Cost Components

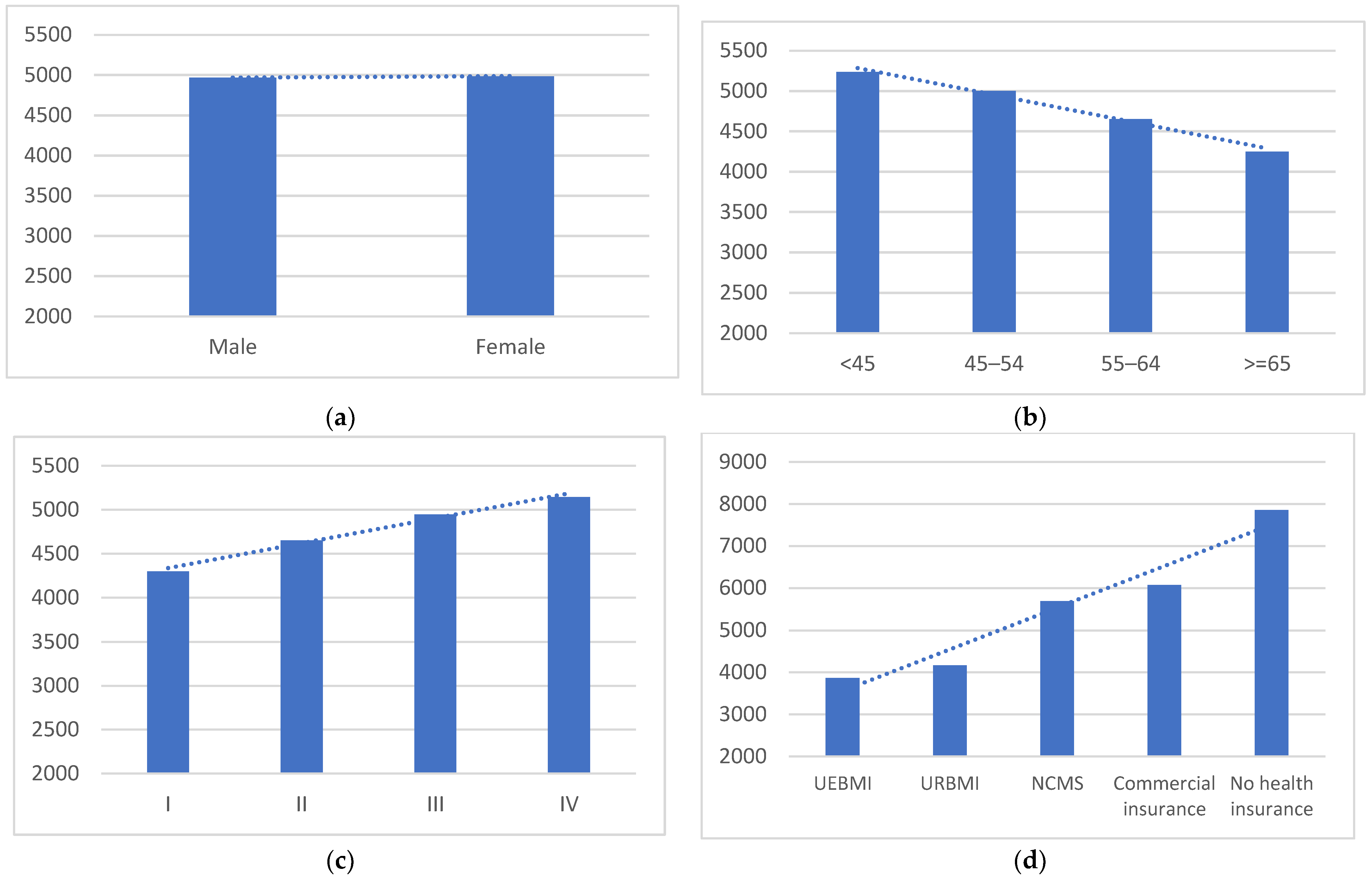

3.2.1. Medical Costs

3.2.2. Nonmedical Costs

3.2.3. Direct Costs

3.2.4. Indirect Costs

3.3. Financial Burden on Households with Cancer Patient and the Coping Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretations

4.2. Policy and Research Implications

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, H.; Cao, S.; Xu, R. Cancer incidence, mortality, and burden in China: A time-trend analysis and comparison with the United States and United Kingdom based on the global epidemiological data released in 2020. Cancer Commun. 2021, 41, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goss, P.E.; Strasser-Weippl, K.; Lee-Bychkovsky, B.L.; Fan, L.; Li, J.; Chavarri-Guerra, Y.; Chan, A. Challenges to effective cancer control in China, India, and Russia. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 489–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.; Sharp, L.; Hanly, P.; Barchuk, A.; Bray, F.; Cancela, M.d.C.; Gupta, P.; Meheus, F.; Qiao, Y.-L.; Sitas, F.; et al. Productivity losses due to premature mortality from cancer in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS): A population-based comparison. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 2021, 127, 3029–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, W.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, S.; Ji, J.S.; Zou, X.; Xia, C.; Sun, K.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Changing cancer survival in China during 2003–15: A pooled analysis of 17 population-based cancer registries. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e555–e567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, N.R.; Qu, L.G.; Chao, A.; Ilbawi, A.M. Delays and Barriers to Cancer Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2019, 24, e1371–e1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayakumar, S.; Solomon, E.; Isaranuwatchai, W.; Rodin, D.L.; Ko, Y.-J.; Chan, K.K.W.; Parmar, A. Cancer treatment-related financial toxicity experienced by patients in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 6463–6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, J.; Glaze, K.; Oakland, S.; Hansen, J.; Parry, C. What do 1281 distress screeners tell us about cancer patients in a community cancer center? Psycho-Oncol. 2011, 20, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Guay, M.; Ferrer, J.; Rieber, A.G.; Rhondali, W.; Tayjasanant, S.; Ochoa, J.; Cantu, H.; Chisholm, G.; Williams, J.; Frisbee-Hume, S.; et al. Financial Distress and Its Associations with Physical and Emotional Symptoms and Quality of Life among Advanced Cancer Patients. Oncologist 2015, 20, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, L.; Carsin, A.E.; Timmons, A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2013, 22, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, S.; Aielli, F.; Adile, C.; Bonanno, G.; Casuccio, A. Financial distress and its impact on symptom expression in advanced cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 29, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council People’s Republic of China. Current Major Project on Health Care System Reform (2009–2011). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-04/07/content_1279256.htm (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- People.cn. 20 Diseases Were Included in the Rural Catastrophic Insurance. Available online: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/0117/c70731-20226865.html (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- National Health and Family Planning Commission (Now as National Health Commission). Division for Medicine Policy and Essential Medicines, Notice of National Negotiation on Pooled Procurement. 2016; No. 19. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yaozs/s3577/201605/15fb339b6b854b8981dee3306d76ce27.shtml (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Li, K.Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Q. Overview and Analysis on the National Medical Insurance Negotiation Drugs over the Years: Taking Anti-cancer Drugs as an Example. Anti-Tumor Pharm. 2021, 11, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- National Healthcare Security Administration; Ministry of Human Resource and Social Security. Notice on Issuing the National Drug Catalog for Basic Medical Insurance, Work-Related Injury Insurance, and Maternity Insurance. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-12/28/content_5574062.htm (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- National Healthcare Security Administration, Ministry of Finance. Notice on Improving Basic Medical Security for Urban and Rural Residents in 2019. 2019; No. 30. Available online: http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2019/5/13/art_37_1286.html (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- STROBE. Checklist of Items That Should Be Included in Reports of Observational Studies. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/checklists/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Lo, C.K.; Mertz, D.; Loeb, M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: Comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Circum Network’s Quality Criteria for Survey Research. Available online: https://circum.com/index.cgi?en:appr (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Exchange Rates, UK. Available online: https://www.exchangerates.org.uk/ (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- China Statistical Yearbook. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj./ndsj/ (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Barker, T.H.; Migliavaca, C.B.; Stein, C.; Colpani, V.; Falavigna, M.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: A guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.H.; Feng, Y.; Jin, Y.C.; Gu, A.Q.; Chen, Z.W. Study on the Economic Burden of Lung Cancer Inpatients from One Tertiary Hospital in Shanghai. Chin. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 32, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Lu, Q.Y.; Gao, Y.X. The trend of inpatient cost of elderly cancer patients without healthcare insurance from 2002 to 2009 in Nantong. Chin. J. Gerontol. 2012, 32, 350–352. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Huang, A.M.; Tao, L.N.; Zhong, H. Trends of Clinical Features and Direct Medical Costs in Patients with Lung Cancer from 2000 to 2009. China Cancer 2013, 22, 666–670. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.M. Analysis of Hospitalization Expenses of Malignant Tumors in Patients with Medical Insurance. China Health Insur. 2014, 5, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Wei, S.Z.; Xiang, L. Analyzing the hospitalization expense and insurance from NCMS for patient with 7 kinds of cancer in one City. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 2014, 31, 522–524. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Y.; Qian, D.F.; Zhou, S.J.; Mao, Z.Z.; Hu, D.W.; Lyu, J. Study or rural-urban differences of direct economic burdens of lung cancer inpatients in a area. Chongqing Med. 2016, 45, 661–663. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Cheng, J.; Chai, J.; Feng, R.; Liang, H.; Shen, X.; Sha, R.; Wang, D. Inpatient care burden due to cancers in Anhui, China: A cross-sectional household survey. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.-Y.; Shi, J.-F.; Guo, L.-W.; Bai, Y.-N.; Liao, X.-Z.; Liu, G.-X.; Mao, A.-Y.; Ren, J.-S.; Sun, X.-J.; Zhu, X.-Y.; et al. Expenditure and financial burden for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer in China: A hospital-based, multicenter, cross-sectional survey. Chin. J. Cancer 2017, 36, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.H.; Zhu, W.J.; Li, J.R. Analysis of Economic Burden of Illness for Cancer Patients in Hubei Province. Med. Soc. 2017, 30, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, X.-Z.; Shi, J.-F.; Liu, J.-S.; Huang, H.-Y.; Guo, L.-W.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Xiao, H.-F.; Wang, L.; Bai, Y.-N.; Liu, G.-X.; et al. Medical and non-medical expenditure for breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in China: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Asia-Pacific J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.Y.; Wang, Q. Comparative Analysis of Expenses of Outpatient and Hospitalization of Patients with Malignant Tumor of a Third-Level Grade-A Hospital in Guangzhou City. Med. Soc. 2018, 31, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.L.; Wu, D.X.; Liu, S.F.; Zhang, Z.G.; Geng, Y.S. Analysis on the Disease Constitutes of Patients Acquired Medical Assistance for Catastrophic Diseases in Wanquan County of Hebei from 2012 to 2016. Med. Insur. 2018, 37, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.J.; Meng, Y.; Wang, S.Y.; Lyu, B.Y.; Lyu, H. Analysis of disease incurring poverty and its cost burden in Nanyang city of Henan province. Chin. J. Hosp. Adm. 2018, 34, 588–592. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, G.L.; Liang, L.Z.; Zhang, Z.F.; Liang, Q.L.; Huang, Z.Y.; Zhang, H.J.; Cheng, S.A.; Peng, X.X. Hospitalization costs of treating colorectal cancer in China: A retrospective analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e16718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Cheng, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zong, J.; Sun, W.; Xu, L.; Soriano-Gabarró, M.; Song, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhan, S. Prostate cancer with bone metastasis in Beijing: An observational study of prevalence, hospital visits and treatment costs using data from an administrative claims database. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.X.; Zang, S.J.; Leng, A.L.; Wang, J. Analysis of the proportion of drug expenses and medical insurance payment based on hospitalization expenses of five cancer patients. J. Shandong Univ. 2019, 57, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H.; Lei, L.; Shi, J.; Wu, Y.; Liang, L.; Huang, H.; He, M.; Bai, F.; Cao, M.; Qiu, H.; et al. No expenditure difference among patients with liver cancer at stage I-IV: Findings from a multicenter cross-sectional study in China. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 32, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, M.; Zeng, X.; Tan, W.J.; Tao, S.; Liu, R.; Liu, B.; Ma, W.; Huang, W.; Yu, H. Catastrophic health expenditures of households living with pediatric leukemia in China. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 6802–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Yin, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.; Shi, J.; Dai, M. Expenditure and Financial Burden for Stomach Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in China: A Multicenter Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.T.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Y. Financial burden of 184 esophageal cancer patients from a cancer specialized hospital. Jiangsu Health Syst. Manag. 2020, 31, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Shi, X.; Nicholas, S.; Ma, Y.; He, P. Estimated annual prevalence, medical service utilization and direct costs of lung cancer in urban China. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 2914–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Shi, J.-F.; Fu, W.-Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.-X.; Chen, W.-Q.; He, J. Catastrophic health expenditure and its determinants in households with lung cancer patients in China: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.X.; Liang, W.J.; Huang, K.Y. Catastrophic health expenditure and its influencing factors among cancer patients in Nanning City. J. Guangxi Med. Univ. 2021, 38, 816–820. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, S.; Mao, W.; Akinyemiju, T. Socio-Economic and Rural-Urban Differences in Healthcare and Catastrophic Health Expenditure Among Cancer Patients in China: Analysis of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 779285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Bertwistle, D.; Khela, K.; Middleton-Dalby, C.; Hall, J. Patient and caregiver socioeconomic burden of first-line systemic therapy for advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, A.; Jing, J.; Nicholas, S.; Wang, J. Catastrophic health expenditure of cancer patients at the end-of-life: A retrospective observational study in China. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Fu, W.; Zhao, X.; Hu, T.W. Economic Burden for Lung Cancer Survivors in Urban China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Li, X. Direct and indirect costs of families with a child with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in an academic hospital in China: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.Y.; Xu, F.Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Sun, X.J. Analysis on Long-term Treatment Expenses of Four Kinds of Cancers and Its Influencing Factors. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 2019, 36, 740–742, 772. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Cai, S.; Jin, M.; Jiang, C.; Xu, N.; Duan, C.; Peng, X.; Zhao, J.; Ma, X. Economic burden for retinoblastoma patients in China. J. Med. Econ. 2020, 23, 1553–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, Y.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Li, L.; Sriplung, H.; Wang, Y.; You, J.; Ma, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Shen, T.; et al. Financial burden on the families of patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver diseases and the role of public health insurance in Yunnan province of China. Public Health 2016, 130, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Wushouer, H.; Huang, C.; Luo, Z.; Guan, X.; Shi, L. Health Care Utilization and Costs of Patients with Prostate Cancer in China Based on National Health Insurance Database From 2015 to 2017. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Wu, Z.; Yang, L.; Yu, L.; Deng, J.; Luk, K.; Zhang, L. Disparities in economic burden for children with leukemia insured by resident basic medical insurance: Evidence from real-world data 2015–2019 in Guangdong, China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.J.; Chen, N. Study on the Characteristics of Liver Cancer and Its Economic Burden Based on Cluster Analysis in a City in Jiangsu Province. Med. Soc. 2022, 35, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.E.; Lou, V.W.; Jian, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, M.; Zhu, J.; He, Y. Objective and subjective financial burden and its associations with health-related quality of life among lung cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.Y.; Shi, J.F.; Fu, W.Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.X.; Chen, W.Q.; He, J. Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Its Determinants among Households with Breast Cancer Patients in China: A Multicentre, Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 704700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; China Working Group on Colorectal Cancer Survey; Ma, L.; Gu, X.-F.; Li, L.; Wang, W.-J.; Du, L.-B.; Xu, H.-F.; Cao, H.-L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Out-of-pocket medical expenditure and associated factors of advanced colorectal cancer in China: A multi-center cross-sectional study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Hu, L.; Han, X.; Cao, M.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Financial toxicity in female patients with breast cancer: A national cross-sectional study in China. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 8231–8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, W.; Fu, H.; Chen, A.T.; Zhai, T.; Jian, W.; Xu, R.; Pan, J.; Hu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: Progress and gaps in Universal Health Coverage. Lancet 2019, 394, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on Cancer: Setting Priorities, Investing Wisely and Providing Care for All; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0; IGO World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Tao, W.; Zeng, Z.; Dang, H.; Lu, B.; Chuong, L.; Yue, D.; Wen, J.; Zhao, R.; Li, W.; Kominski, G.F. Towards universal health coverage: Lessons from 10 years of healthcare reform in China. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Jian, W.; Zhu, K.; Kwon, S.; Fang, H. Reforming public hospital financing in China: Progress and challenges. BMJ 2019, 365, l4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, W.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, H.; Shang, L.; Li, X. Impact of the National Health Insurance Coverage Policy on the Utilisation and Accessibility of Innovative Anti-cancer Medicines in China: An Interrupted Time-Series Study. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 714127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.N. Epidemic trend, screening, and early detection and treatment of cancer in Chinese population. Cancer Biol. Med. 2017, 14, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Su, M.; Yao, N.; Liu, L.; Cheng, J.; Sun, X.; Yue, H.; Zhang, J. Older cancer survivors living with financial hardship in China: A qualitative study of family perspectives. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramesh, C.S.; Badwe, R.A.; Bhoo-Pathy, N.; Booth, C.M.; Chinnaswamy, G.; Dare, A.J.; de Andrade, V.P.; Hunter, D.J.; Gopal, S.; Gospodarowicz, M.; et al. Priorities for cancer research in low- and middle-income countries: A global perspective. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.; McGowan, C.; McKee, M.; Suhrcke, M.; Hanson, K. Coping with healthcare costs for chronic illness in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic literature review. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, Y.; Trapani, D.; Johnson, S.; Tittenbrun, Z.; Given, L.; Hohman, K.; Stevens, L.; Torode, J.S.; Boniol, M.; Ilbawi, A.M. National cancer control plans: A global analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e546–e555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Tang, M.; Ye, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, D.; Song, P.; Jin, C. China issues the National Essential Medicines List (2018 edition): Background, differences from previous editions, and potential issues. Biosci. Trends 2018, 12, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Impact of zero-mark-up medicines policy on hospital revenue structure: A panel data analysis of 136 public tertiary hospitals in China, 2012–2020. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e007089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Mossialos, E. Pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement in China: When the whole is less than the sum of its parts. Health Policy 2016, 120, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Type of Cancer | Number of Patients | Study Year | Duration of Costs | Data Source | Mean/Median/Both | Component of Costs | Breakdown of Direct Costs | CHE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Costs | Non-MD | |||||||||||||

| Direct | Indirect | Total | Total | INPT | OPT | |||||||||

| Huang, 2012 a,* [24] | lung cancer | 402 | 2010–2011 | annual | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Xiao, 2012 [25] | multicancer (the elderly) | 973 | 2009 | annual | medical record | mean | √ | |||||||

| Peng, 2013 [26] | lung cancer | 1216 | 2009 | annual | survey and basic health insurance database | mean | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Jin, 2014 [27] | cancer | 5062 | 2012 | annual | basic health insurance (UEBMI) database | mean | √ | |||||||

| Xiao, 2014 [28] | cancer | 4854 | 2010–2012 | annual | basic health insurance (NRCMS) database | mean | √ | |||||||

| Li, 2016 c,* [29] | lung cancer | 218 | 2014 | annual | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Zhao, 2016 * [30] | multicancer | 318 | 2014 | annual | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Huang, 2017 * [31] | colorectal cancer | 2356 | 2012–2014 | annual b | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Lin, 2017 * [32] | multicancer | 252 | 2015–2016 | annual | survey and basic health insurance database | mean | √ | |||||||

| Liao, 2018 * [33] | breast cancer | 2746 | 2012–2014 | annual b | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Xie, 2018 [34] | cancer | OPT: 959 | 2014–2016 | annual | basic health insurance (UEBMI) database | mean | √ | √ | ||||||

| INPT: 838 | ||||||||||||||

| Du, 2018 [35] | cancer-poor population | 207 | 2012–2016 | annual | medical assistance database | mean | √ | |||||||

| Zhang, 2018 [36] | cancer-poor population | 122 | 2017 | annual | survey | mean | √ | |||||||

| Yuan, 2019 [37] | colorectal cancer | 8021 | 2012–2016 | annual | medical record | mean | √ | |||||||

| Zhuo, 2019 [38] | prostate cancer | 1672 | 2011–2014 | annual | basic health insurance (UEBMI) database | both | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Yang, 2019 [39] | multicancer | 20,138 | 2013–2017 | annual | medical record | mean | √ | |||||||

| Lei, 2020 * [40] | liver cancer | 2223 | 2012–2014 | annual b | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Sui, 2020 a,# [41] | pediatric leukemia | 242 | 2018 | annual | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Zhang, 2020 * [42] | stomach cancer | 2401 | 2012–2014 | annual b | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Chen, 2020 *,# [43] | esophageal cancer | 184 | 2019 | annual | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Zhu, 2021 [44] | lung cancer | 38,199 | 2013–2016 | annual | basic health insurance (UEBMI, URBMI) database | mean | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Sun, 2021 a,* [45] | lung cancer | 2565 | 2015–2016 | annual b | survey | mean | √ | √ | ||||||

| Huang, 2021 * [46] | cancer | 332 | 2015–2016 | annual b | survey | mean | √ | √ | ||||||

| Zhao, 2021 * [47] | cancer | 2011:53; 2015:111 | 2011, 2015 | annual | CHARLS (population based) | both | √ | √ | ||||||

| Xiao, 2022 # [48] | advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma | 66 | 2019 | annual | survey | both | √ | |||||||

| Total number of studies | 25 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 12 | 5 | 8 | 5 | |||||

| Leng, 2019 *,# [49] | cancer patients at the end of life | 792 | 2013–2016 | monthly | survey | mean | √ | √ | ||||||

| Zhang, 2017 a,* [50] | lung cancer | 195 | 2014 | 5 years | survey | mean | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Ren, 2019 * [51] | children with lymphoblastic leukemia | 161 | 2010 | during the first three-phase treatment | survey | both | √ | √ | ||||||

| Yaun, 2019 [52] | multicancer | 349 | 2016 | during the illness | basic health insurance database | mean | √ | |||||||

| Zhou, 2020 [53] | children with retinoblastoma | 50 | 2015–2017 | during the illness | survey and medical records | mean | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Che, 2016 * [54] | liver cancer | 131 | 2013 | annual | survey and medical records | median | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Bai, 2020 [55] | prostate cancer | 3936 | 2017 | annual | basic health insurance (UEBMI, URBMI) database | median | √ | |||||||

| Zhan, 2022 [56] | children with leukemia | 765 | 2015–2019 | during the illness | medical record | median | √ | |||||||

| Zhang, 2022 [57] | liver cancer | 8969 | 2011–2017 | annual | basic health insurance database | median | √ | |||||||

| Chen, 2018 [58] | lung cancer | 227 | 2016 | monthly | survey | both | √ | |||||||

| Sun, 2021 [59] | breast cancer | 639 | 2015–2016 | -- | survey | -- | √ | |||||||

| Wang, 2022 # [60] | colorectal cancer | 4428 | 2020–2021 | -- | survey | -- | ||||||||

| Liu, 2022 # [61] | breast cancer | 627 | 2021 | -- | survey | -- | ||||||||

| Total number of all included studies | 38 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 22 | 15 | 7 | 12 | 9 | |||||

| Study | Participants | Cancer Patients (n) | Year | Data Source | Definition of Medical Cost in the Study | Annual Medical Costs (USD) | Annual Household Income (USD) | Annual OOP Medical Costs/Household Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang, 2012 [24] | lung cancer | 402 | 2010–2011 | survey | inpatient, outpatient, and fees for purchasing drugs from pharmacies | 7420.85 | 13,550.73 | 54.8% |

| Huang, 2017 a [31] | colorectal cancer | 2356 | 2012–2014 | survey | inpatient, outpatient | 5397.75 | 10,013.99 | 53.9% |

| Liao, 2018 [33] | breast cancer | 2746 | 2012–2014 | survey | inpatient, outpatient | 4105.94 | 10,990.09 | 37.4% |

| Lei, 2020 a [40] | liver cancer | 2223 | 2012–2014 | survey | inpatient, outpatient | 4056.78 | 11,259.70 | 36.0% |

| Zhang, 2020 a [42] | Stomach cancer | 2401 | 2012–2014 | survey | inpatient, outpatient | 5524.95 | 9481.50 | 58.3% |

| Sun, 2021 a [45] | lung cancer | 2565 | 2015–2016 | survey | inpatient, outpatient, and fees for purchasing drugs from pharmacies | 8663.51 | 13,725.00 | 63.1% |

| Lin, 2017 [32] | multicancer | 252 | 2015–2016 | survey and basic health insurance database | medical costs related to cancer treatment | 2410.07 | 5265.00 | 45.8% |

| Huang, 2021 a [46] | cancer | 332 | 2015–2016 | survey | medical costs related to cancer treatment | 10,431.25 | 16,893.94 | 61.7% |

| Chen, 2020 b [43] | esophageal cancer | 184 | 2019 | survey | inpatient, outpatient | 4460.12 | 3454.45 | 129.1% |

| Random pooled ES (95%CI) of the proportion of the annual medical cost to annual household income from eight studies | 51% (44%, 59%) | |||||||

| Study | Participants | Cancer Patients | Year | Location | Cooping Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sui, 2020 [41] | pediatric leukemia | 242 | 2018 | Heilongjiang |

|

| Chen, 2020 [43] | esophageal cancer | 184 | 2019 | Anhui | Borrowed money from relatives and friends: 45.10% |

| Xiao, 2022 [48] | advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma | 66 | 2019 | multicountry | Financial support from caregivers: 62.1% |

| Leng, 2019 [49] | cancer patients at the end of life | 792 | 2013–2016 | multicenter | Borrowed money from relatives and friends: 32.10% |

| Wang, 2022 [60] | colorectal cancer | 4428 | 2020–2021 | multicenter |

|

| Liu, 2022 [61] | breast cancer | 627 | 2021 | national |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, Y.; Jiang, W.; Yang, B.; Tang, S.; Long, Q. Cost Drivers and Financial Burden for Cancer-Affected Families in China: A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 7654-7671. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30080555

Jia Y, Jiang W, Yang B, Tang S, Long Q. Cost Drivers and Financial Burden for Cancer-Affected Families in China: A Systematic Review. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(8):7654-7671. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30080555

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Yufei, Weixi Jiang, Bolu Yang, Shenglan Tang, and Qian Long. 2023. "Cost Drivers and Financial Burden for Cancer-Affected Families in China: A Systematic Review" Current Oncology 30, no. 8: 7654-7671. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30080555

APA StyleJia, Y., Jiang, W., Yang, B., Tang, S., & Long, Q. (2023). Cost Drivers and Financial Burden for Cancer-Affected Families in China: A Systematic Review. Current Oncology, 30(8), 7654-7671. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30080555